Give me some scuba kit and a time machine and I’ll set the dial to 380 million years ago, so I can watch strange fish swim through Devonian seas. This is a time when an epic evolutionary experiment is underway, trying out different ways of being a fish. Galeaspids and osteostracans, types of jawless fish, push massive head shields through the water, some bullet-shaped, some like shovels; Doryaspis has a rounded, armour-plated body and a prong sticking forwards like a miniature sawfish; on the seabed, snorkel tubes give away the hiding place of flattened, triangular Eglonaspis. Ancestors of lungfish and coelacanths prey on fidgeting clouds of worm-like fish called conodonts; acanthodians, also known as spiny sharks, glide through the water, their bodies covered in minute, diamond-shaped scales and with sharp prongs adjacent to each fin.

Most of all I want to meet the placoderms, the armoured fish that rule these seas. Tiny placoderms, small enough to fit inside a matchbox, have armoured fins sticking out stiffly to the sides – these are fish with arms, of sorts. Flattened placoderms lie on the seabed like stingrays (although these elasmobranchs didn’t evolve for a while to come). And dark shadows fall through the water as the world’s first vertebrate super-predators cruise around. There are at least 10 Dunkleosteus species, with giant, thick-set heads covered in armoured shields that extend into their jaws, forming fangs that slice past each other like gigantic, self-sharpening garden shears. Placoderms are the first fish with jaws, and Dunkleosteus flaunt theirs with terrifying effect. In Devonian seas, sharks are less than a metre (3ft) long and a one-tonne Dunkleosteus, at six metres (20ft), make easy work of swallowing them whole, tail first. For these giant placoderms, there’s little to fear except others of their own kind. Titanic battles break out between these leviathans, perhaps to dispatch competitors or even for a meal. Their enormous fangs punch deep holes, slamming their jaws shut with a bite force three times more powerful than today’s huge aquatic predators, the Great White Sharks and Saltwater Crocodiles. A pair of fighting Dunkleosteus bite again and again, until eventually the winner feels its rival’s armour crack and give way.

In truth, of course, no divers will ever get a chance to watch a living placoderm, or any other ancient fish. But knowing about this lost world tells us much about how the fish we see today came to be.

Modern fish wouldn’t rule the aquatic realm in the ways they do today were it not for their ancestors who thrived and survived for hundreds of millions of years. Looking into the past we can see how ancient fish adapted and repeatedly reinvented themselves while all around them life on Earth was rising and falling. They were the first to evolve many important characters that are still around today, like jaws; the articulated bones in your mouth that let you chew and grin have been vital in vertebrate evolution, allowing diverse and efficient ways of feeding. Ancient fish also experimented with a host of other features that didn’t persist but were added to a catalogue of vanished oddities – all of them playing their part in the illustrious dynasty of fish.

We know so many details of these ancient lives because people have learned how to read rocks. Palaeontologists are piecing together a more detailed view than ever of ancient underwater life. They interpret fossilised bones and impressions left by bodies pressed into stone, and reconstruct the way fish used to be.

Stunning insights into the past have come from various parts of the world where exquisite fossils can be found. One such spot is a huge limestone escarpment, called the Gogo Formation, standing in a remote desert in the Kimberley, the northernmost region of Western Australia. Preserved inside Gogo are scores of animals from Australia’s first Great Barrier Reef, which flourished in the Devonian period and skirted 1,400km (870 miles) along the edge of the southern supercontinent, Gondwana. When reef fish died, their bodies drifted into deep-water bays next to the reef and were swiftly buried in mud and sealed inside limestone nodules that kept the bodies intact and un-squashed. Fish fossils were first found here in the 1940s and since then teams have returned to carefully chip the nodules away. Like a palaeontologist’s perfect prehistoric Easter egg, the nodules are then opened up to find the treats that lie within. In museum laboratories the nodules are gently dunked in baths of acetic acid, the same strength as vinegar, which gradually dissolves the surrounding limestone and reveals the intricate, three-dimensional fish skeletons. Not only are the fish’s bones and armour plates preserved, but also their soft insides. There are individual muscle fibres and nerve cells set in stone that contracted for the last time and sent their final electrical messages roughly 380 million years ago.

There are also tiny fish inside other fish. Originally these were thought to be fossilised snapshots of predation and the larger fish’s last meal. But there were no signs of chewing and crunching, or of stomach acid etching the smaller fish’s bones. Then John Long, a Gogo-Formation expert now at Flinders University in Adelaide, examined a fossil placoderm that turned out not to be another fish’s dinner but an unborn embryo. His research team found a tiny umbilical cord, with a slight helical twist, connecting the embryo to its mother. In 2008 they named her Materpiscis attenboroughi – Materpiscis meaning ‘mother fish’ in Latin, and attenboroughi in honour of Sir David Attenborough, who featured the Gogo Formation in his 1970s television series Life on Earth.

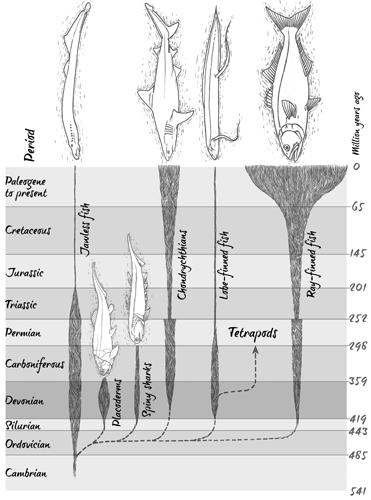

The origins and extinctions of the major fish groups (widths of the spindles roughly indicate the diversity of each group).

At a lecture in London in 2010 for the International Commission for Zoological Nomenclature (the naming of species), Attenborough shared his recollections of that filming trip. His Australian collaborators had assured him there would be nothing to see at Gogo because all the good fossils had already been found and carted off to museums. Attenborough insisted that he would nevertheless like to film at the site where these extraordinary fish had been found, and, grudgingly, a helicopter ride was arranged to take his film crew up to the Kimberley.

When they arrived, Attenborough said in his lecture, ‘I stepped out of the helicopter and I put my foot on a boulder, and on the boulder was a rectangular scute.’ It was undoubtedly the remains of an armoured placoderm, one of the fossils he’d been told were all cleared out. Attenborough described how he turned to his sceptical collaborator and asked what it was. The Australian’s response, he said was ‘You bastard!’ Everyone in the audience roared with laughter at this, and Attenborough chuckled. ‘But,’ Attenborough added, ‘he was decent enough to let me keep it.’

In his lecture, Attenborough went on to describe what happened when, years later, John Long got in touch to tell him about a newly discovered placoderm that would bear his name. Naturally Attenborough was delighted, ‘and then I thought, of course, if you have internal fertilisation then you must actually copulate.’ He paused for a moment to let this idea sink in. ‘This is the first known example of any vertebrate copulating in the history of life, and he named it after me!’ Again the audience burst out laughing. ‘So,’ lamented Attenborough, ‘this has been a source of some concern for me.’

David Attenborough has, however, been let off the hook, because a few years after that lecture John Long went on to make a further discovery. On a visit to the University of Technology in Tallinn, Estonia, he was sifting through a box of placoderm fossils when he spotted an L-shaped bone; he realised it was a sperm-delivering clasper, the same sort of anatomy that male sharks and rays mate with today (although derived from a different part of the body). The discovery sparked a hunt through museum and private fossil collections, which turned out many more male appendages from the same placoderm species. This wasn’t the first time people had found placoderm claspers, but these came from the oldest species so far, and probably a few million years older than Materpiscis attenboroughi. These, then, are the most ancient genitalia known in the fossil record, and markers of the origin of vertebrate sex. They confirm that internal fertilisation and live birth, as practised by many but not all placoderms (some laid eggs), evolved early on among these fish. Subsequently most living fish, especially teleosts, dispensed with this ancient way of doing things and went back to laying eggs.

Elsewhere, other discoveries have revealed details of the next stage of life for these early fish. In Pennsylvania in 2004, a bypass for the Route 15 highway was cut into the slopes of Pine Hill, revealing fossil-filled rocks that had previously been deep underground. Palaeontologists from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia found hundreds of small, hatchling placoderms, with huge eyes and big heads, and deduced that this had been a nursery. Females came to this spot to lay eggs, then left their offspring to it, playing no further role in their upbringing; there were no mature placoderm fossils in the same area. The young succumbed to their habitat drying up; water levels in a quiet backwater rapidly fell and trapped the hatchlings in an isolated pool without enough oxygen to sustain them. Shortly after they died, and before their bodies began to decompose, a layer of mud swept in and settled gently over them, beginning the process of fossilisation and capturing a moment in stone. A similar preserved placoderm nursery has shown up at a quarry in Belgium. These are the oldest known examples of animals from different generations living in distinct places underwater, just as many species divide up their realms today between young and old.

As well as exquisite fossils like the Gogo fish, Devonian seas were also filled with fish that left very little of themselves behind in the fossil record, but there are other ways of peering into their ancient lives. Thelodonts are jawless Devonian fish that are mostly missing from the fossil record. A few very rare intact fossils reveal they were sometimes spindle-shaped, sometimes flattened with wide mouths, like miniature Whale Sharks, and some had upright bodies with large, lobed tails. On the whole, though, all that remain of the thelodonts are sprinklings of their minute scales.

In 2017, Humberto Ferrón and Héctor Botella from the University of Valencia in Spain took a novel approach to working out details of the thelodonts’ lives, despite the scanty fossil evidence. They examined the microscopic shape of their scales and compared them to modern shark denticles, which vary depending on the shark’s ecology: where they live, how they move and so on. Making the reasonable assumption that similar associations between scales and habits and habitats applied to thelodonts as in sharks, Ferrón and Botella suggested these ancient fish led a variety of different lifestyles. There were thelodonts that perched on the seabed, hiding in caves and crevices in reefs, as shown by their abrasion-resistant scales; others swam in schools and had spiky scales that deterred ectoparasites from hitching on; and some bore the hallmarks of speed in their drag-resistant scales, etched with ridges and riblets, just as in fast-swimming sharks. There’s also a thelodont that had scales similar to those on living bioluminescent sharks, which allow light to pass through the skin. Ferrón and Botella are cautiously waiting for more specimens to study before they go ahead and make any bold claims that thelodonts could glow in the dark.

Thelodonts, as well as galeaspids, osteostracans, conodonts and many other jawless fish, occupy branches down at the base of the fish evolutionary tree, among the direct ancestors of lampreys and hagfish. Exactly how these early branches of the jawless fish should be arranged remains under discussion, which is perhaps no great surprise; after all, this was a very long time ago.1 As new fossils are found and new ways of looking at them are invented, additional details are being added to the mix. It’s well established that placoderms arose later, snapping their jaws and reaping the benefits of having teeth fixed firmly in place. Then the acanthodians, the ‘spiny sharks’, arose, some of which were (probably) the direct ancestors of sharks and rays.

All of these fish shared Devonian seas with lungfish, coelacanths, sharks and ray-finned fish. But as this period drew to a close, roughly 360 million years ago, it became clear that this would be the only time in the history of life on Earth when this many deep branches of the fish evolutionary tree would remain intact all at the same time. The reign of all these fish wouldn’t last forever.

In the 17th century, when British naturalist John Ray was compiling his unfortunate book De Historia Piscium (‘The History of Fish’) that almost ruined the Royal Society in London, he studied not only living plants and animals but also fossils. And he struggled with questions that would plague him for the rest of his life. How did fossils come to be lodged in rocks, and how were they made?

At the time, various theories were proposed to explain the appearance and disappearance of fossils. A widely held idea was that fossils were exuded by the rocks themselves as they tried to impersonate living things. Another was that they were sea creatures that had been swept onto land during the great, biblical flood. John Ray was unconvinced by both these ideas. He was a religious man, and while he conceded that some but not all fossils could have stemmed from the deluge of Noah’s time, he’d seen for himself that fossils don’t all lie together in the same layer of rocks, as you’d expect if they had all been laid down by a single, catastrophic flood. Instead, he found fossils scattered through discrete beds in many different places he visited. To make matters worse, all that rain and flooding would surely have swept creatures out to sea, not the other way round. He doubted that a great flood would sweep animals from the sea onto land or indeed up mountains.

On his travels, Ray visited the Mediterranean island of Malta, and saw in rocks high in the mountains neat, triangular stones that at the time were known as glossopetrae (from Greek words glossa and petra, meaning ‘tongue’ and ‘stone’). In the middle ages, people believed these tongue-stones held great powers, and wore them as pendants or sewed them into special pockets in their clothes. In the event of a snakebite, you could whip out the triangular stone and press it against the wound in the hope it would save your life. And if you suspected someone was trying to poison you, you could simply drop a glossopetrae into your glass of wine as a pre-emptive antidote. Pliny the Elder wrote about these stones falling from the heavens during eclipses of the moon, while others believed that they were the petrified tongues of snakes or dragons. John Ray, on the other hand, could quite clearly see that these stones looked like sharks’ teeth.

Earlier in his trip, in Montpellier in France, Ray met with the Danish anatomist Nicolas Steno and it’s likely the pair discussed the origins of fossils. Steno is best remembered for his close encounter with a Great White Shark. By the time he saw it, the shark was no more than a dismembered head. The animal had been spotted swimming off the west coast of Italy by fishermen who apparently caught it in a sling and brought to land, tied it to a tree and beat it to death. The shark’s head was taken to Florence, where Steno dissected and examined various anatomical details, including the pores dotting its snout, and which were later described by one of Steno’s students, Stefano Lorenzini (whom the electro-sensitive ampullae of Lorenzini were named after). Seeing the Great White’s teeth up close, Steno was convinced the stony glossopetrae must have come from sharks whose teeth fell out a long time ago and were buried in layers of mud that preserved them, changing their chemical composition and turning them to stone.2

Steno wasn’t the first to figure out the true identity of tongue-stones, but he made a strong case that began to shift prevailing views on the origins of fossils. Recognising sharks’ teeth in rocks was one thing, but John Ray faced a further conundrum in the fossils that look nothing like any known living animals. Could these fossilised animals have lived a long time ago and since become extinct? The idea flew in the face of his religious beliefs. In Ray’s view, it was impossible that a benevolent and wise god would let his perfect creations – his creatures – die out. Extinction simply wasn’t on the cards. Nevertheless, Ray found a way around the problem and believed that those exotic animals trapped in stone must still exist somewhere on Earth; it was just a matter of time before someone found them. In essence, it’s not such an improbable idea. After all, coelacanths were thought to have been extinct for millions of years, right up until a living one was caught off South Africa in 1938. But coelacanths are a highly unusual case. There almost certainly aren’t any covert dinosaurs wandering through untouched rainforests, or giant, prehistoric sharks lurking at the bottom of the Marianas Trench. With all the explorers scouring the planet today, someone would probably have spotted one by now.

The idea of extinction only really began to take hold in the following century, thanks to the work of the French zoologist Georges Cuvier. At the same time that he was compiling a catalogue of all the world’s living fish in his Histoires Naturelles des Poissons, Cuvier was also planning to do the same thing for all the known fossil fish.

In 1831, a few months before Cuvier died, he was visited at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris by a young Swiss scientist called Louis Agassiz. They had been corresponding for a while, and Cuvier was impressed by Agassiz’s manuscript on fish from the River Amazon. Agassiz was planning to write a book on the fossil fish of central Europe and was initially worried he might be treading on Cuvier’s toes, but after his visit to Paris he came away with a much grander ambition. For several months Cuvier mentored Agassiz and, recognising his skill and devotion to the subject, handed over all his notes and drawings of fossil fish from the Paris museum’s fine collections. Agassiz then spent years studying these fossils and many more from across Europe, including from the old red sandstones of Scotland, and between 1833 and 1843 published five lavishly illustrated volumes of Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (‘Studies of fossil fish’). Across the pages of his books were thousands of detailed drawings of fossils, including some that people thought at the time might be turtles or giant beetles. Agassiz called them placoderms, although he thought they were jawless fish (specimens showing the insides of their skulls and the structure of their jaws were only studied in the 1920s). These strange fish were unlike any still swimming around, and Cuvier would undoubtedly have been convinced they were extinct species.

Years previously, Cuvier had put forward evidence for this theory of extinction. He conducted detailed anatomical studies of elephant bones dug up near Paris. From their size and shape, he concluded they were most definitely not from elephant species still alive in India and Africa. He argued that there couldn’t possibly be a third living species hiding somewhere. Elephants are just too big to miss. The bones from Paris must have come from an elephant that was no longer around (he later named them mastodons). Cuvier wrote, ‘All of these facts ... seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.’ He came to conclude that repeated revolutions, as he called them, hit many millions of years apart, each time wiping out swathes of life on Earth.

Cuvier’s revolutions are now generally known as mass extinctions, and so far in Earth’s history there have been five of them. Each episode was triggered in its own way, although often involving rapid changes in global climate, and each dispatched particular groups of living things.

The first mass extinction took place at the end of the Ordovician period, around 443 million years ago, wiping out more than half of all life in the seas. The second event was a series of extinction pulses that swept through the seas towards the end of the Devonian. Immense areas of tropical reefs, like the Gogo Formation, died off. Three-quarters of fish groups went extinct. Jawless fish dwindled. Conodonts suffered major losses; thelodonts were lost; the last of the galeaspids and osteostracans swam around and their giant, armoured heads would be missed from the oceans from then on. Coelacanths became rare, and lungfish were driven out of the sea and only survived in freshwaters. And the placoderms were no more.

The forces behind this colossal upheaval are thought to have come from above the waterline. Around this time, animal life on land was just getting started. Pioneering invertebrates had been crawling around out of water for a while, and amphibians were beginning to pad about on their newly evolved legs. Plants, meanwhile, were exploring the land in a whole new way. They’d been lingering at the waters’ edge and in damp places for perhaps 100 million years already, but by the late Devonian they made a break for the open reaches of dry land. For the first time tall trees towered into the sky. Forests spread, and dense canopies of leaves were busy photosynthesising, soaking up carbon dioxide on a vast scale. This thinned the insulating layer of the greenhouse gas – the opposite of what’s happening with human carbon emissions today – and the Earth’s temperature tumbled into an ice age. Water froze into glaciers, sea levels dropped and shallow seas drained away where so much life had recently thrived.

The greening continents may have turned the oceans green too, ultimately sapping them of oxygen and killing off yet more sea life. Plants’ roots pushed deep into rocks, breaking them apart, building up soils and releasing nutrients that washed out to sea. This could have nourished great blooms of planktonic algae, smearing bright, swirling stains across the sea. And when all that algae died and sank to the seabed, bacteria would have decomposed the abundant carcasses, soaking up oxygen from the water and creating dead zones where few living things can survive.3

It’s still not fully understood or agreed upon why certain groups of species, and especially among the fish, succumbed to the end-Devonian extinctions that raged for millions of years. What is clear is that the oceans were radically rearranged. The placoderms were no longer the dominant predators, patrolling the open seas and picking prey from the seabed. In their wake they left great gaps in aquatic ecosystems that were waiting to be filled. And one group of fish in particular made the most of them.

Carnival of the sharks

In the US state of Montana, at a rock formation known as Bear Gulch, are the remains of a shallow bay that once lay at the edge of a vast ocean. For decades, palaeontologists have been chipping away at this 30m- (100ft-) thick limestone deposit that formed in the Carboniferous, around 318 million years ago. The Bear Gulch fossils give an indication of what happened after so much was lost at the end of the Devonian. This was a time when the sharks and their relatives became the leading characters in a curious new aquatic world.

On the bottom of the bay perched Balanstea, sharks with stubby tails, flouncy fins and upright bodies shaped like crooked leaves. They were not speedy swimmers but could deftly manoeuvre, grabbing invertebrates encased in hard shells and crunching them between knobbly tooth-plates, fashioned into a beak. In open water, a common sight were large schools of Falcatus sharks. It was easy to tell which of them were male and which female. Females, with torpedo-shaped bodies, looked similar to living Spiny Dogfish, although much smaller at only 15cm (6in) long, the size of a hotdog. The males had claspers, modified fins for delivering sperm, and also an additional appendage fashioned from an elongated fin spine fixed to their foreheads and bent forwards as far as the tip of their snout. Richard Lund, a leading specialist in Bear Gulch fossils, has found specimens that hinted at what this spine was used for. A fossilised female Falcatus has her jaws clamped tightly to a male’s appendage. As fossils, the couple lay together, although the wrong way round for what you might imagine they were up to: the female is on top with her belly pressed against her partner’s back. Perhaps this was part of some ancient foreplay.

Another item of bizarre headgear was attached to sharks that were shaped like eels, called Harpagofututor. The males had pairs of long antennae sticking up in front of their eyes, forked at the end like crab claws. These, we can presume, were used in a similar way to how living chimaeras use their head-mounted, retractable organs in crucial moments to keep their mates close by.

Swimming around Bear Gulch bay were yet more sharks called Stethacanthus. Two species have been found. One was almost 3m (9ft) long, the other was the size of an Atlantic Salmon (70cm, 27in), and both had peculiar things on their heads. Male Stethacanthus had what looked like an enormous toothbrush fixed to their dorsal fin, and another brush between their eyes.

Fossils of Stethacanthus have been known of for more than a century, but still all we have are wild ideas about why they evolved such bizarre embellishments. Perhaps females picked out the males with the biggest, most impressive head-brushes (male Stethacanthus also had long spines, known as fin whips, trailing behind their pectoral fins, which could have played some part in mating rituals). Maybe males postured their bristles at each other while arguing over females, or perhaps they fought in head-to-head battles like deer, only instead of locking antlers they rubbed their brushes together.

The head-brushes probably did have something to do with mating, but there are other suggestions, too. A study published in 1984 points out that the spiny brushes have a similar microstructure to human erectile tissue, so perhaps the Stethacanthus brushes were similarly inflatable. Could they have put off predator attacks by engorging their brushes to imitate the giant jaws of a much larger, more dangerous fish? Maybe. Another idea is that these peculiar sharks used their head-brushes to hitch a ride on the bellies of larger sharks, like remoras and shark-suckers do today. If they did, then Stethacanthus would have had a unique way of doing it, sticking themselves in place with their very own version of Velcro.

The strange-looking sharks weren’t alone in Bear Gulch. Ray-finned fish were there, as they too were expanding their ranges and diversifying after the placoderms vacated the seas. There were various coelacanths and one of the oldest known lampreys, Hardistiella, showing that some jawless fish did manage to survive the Devonian extinctions, though they would never again be as widespread as they once were. There were also other, less eccentric sharks. There were chimaeras that looked a lot like the ones alive today, and some species known only from a few scales and teeth, so there’s no knowing what these animals looked like or how strange they might have been. And the chondrichthian oddities were by no means confined to Bear Gulch. For millions of years to come, after the Carboniferous period, sharks all across the oceans were still experimenting and coming up with unusual results.

When elegant, spiral-shaped fossils were first found in rocks they were assumed to be ammonites, the extinct relatives of octopuses and nautiluses. They were of a suitable size, often around 20cm (8in) across, and formed an approximate logarithmic spiral (one that expands outwards at a constant rate). Then it was pointed out that they look not so much like seashells as like sharks’ teeth. No skeletal remains have come to light, so we can only guess at what the rest of these sharks from the Permian (from around 290 million years ago) looked like. Based on the size of their teeth, they may have been on average around four metres (13ft) long, and perhaps much more than that. An enticing mystery is where on their bodies those jagged spirals belonged.

For more than a century, palaeontologists have imaged various permutations of Helicoprion, as the group of extinct species came to be known. The spirals have dangled from the end of a shark’s tail or swept backwards on a dorsal fin, or stuck out at the end of an elongated lower jaw like a pizza-cutter. One arrangement even imagines the circular teeth embedded side-on in the flat belly of a stingray. It was only in 2013 that researchers from the Idaho Museum of Natural History published a study of a fossil that shed new light on things. Led by Leif Tapanila, the team took out of storage a fossilised spiral that was originally excavated in the 1950s, and put it inside a CT scanner. Fragments of cartilage still stuck in place, imaged in three dimensions, revealed that Helicoprion set their spiralling teeth deep within their lower jaw. It was as if they had a circular saw in their mouths, in roughly the place where your tongue lies. Now imagine your tongue has a Mohican of teeth running down its midline, with new ones being continually made at the back of your throat, nudging older ones ahead as the whole thing spirals downwards and inwards. Inside the Helicopiron spiral, the teeth at the centre are the smallest and oldest, made when the animal was young (in a similar way, the central whorl of a mollusc’s shell is the oldest part, which it has had since it hatched). With new images and information, Tapanila and the team found clues that Helicoprion was more closely related to living chimaeras than to sharks and rays, and what’s more, the spirals worked alone. In the upper jaw, it seems Helicoprion had no teeth. And so with one mystery solved, another emerged. How exactly did these animals use this singular, toothy whorl? Again, lots of ideas have been offered up and recent studies of a different extinct fish have offered new clues.

Edestus, a close relative of Helicoprion, had whorls of teeth in both the upper and lower jaws, although they weren’t tight spirals. It had been thought that Edestus used their jaws like giant scissors, but this wouldn’t have worked because their tooth whorls didn’t overlap; imagine using a pair of scissors with the blades bent backwards. Then, in a 2015 study, Wayne Itano from the University of Colorado came up with an alternative idea. His analogy for Edestus jaws is a traditional Polynesian weapon called the leiomano. This flat wooden paddle, like a giant ping-pong bat, has sharks’ teeth fixed to the edge, pointing outwards; it was designed to lacerate the flesh of human enemies. Itano suggested Edestus might have used its teeth to slice at soft-bodied prey, like squid. And he thinks it did this by vigorously nodding its head up and down, with its jaws wide open.

These sharp-jawed predators may even have left behind evidence of their feasting. Fossil Edestus found in Indiana lie in the same rocks as a mass of mutilated bony fish. There were fish with only heads or only tails; one fish had its tail dangling by a thin strip of skin, and another had a wound that nearly sliced its head clean off. For now there’s no firm forensic evidence to blame this massacre on Edestus, but they’re undoubtedly the chief suspects. And perhaps, in their time, Helicoprion did something similar. With their jaws open and their fixed spiral of teeth exposed they could have slashed at schools of squid and fish, as fearsome, head-banging predators.

None of these strange sharks still swim through the oceans today. Most were extinct by the end of the Permian, around 250 million years ago, and they seemed to slip quietly away without unleashing an ecological catastrophe. It would be almost another 200 million years before the oceans were once again shaken up by a mass extinction that changed everything.

Probably the most famous date in the geological calendar is the end of the Cretaceous, around 66 million years ago, when a beloved group of animals bid their final farewell.4 As well as the dinosaurs going extinct, this was a mass extinction that also saw off many other animals, including plenty of fish, large ones in particular.

Swimming their final laps of Cretaceous seas were ray-finned fish that looked a lot like tuna and billfish but belonged to a now extinct group, the pachycormids. Most of them were apex predators that raced through open seas; some had long rostra sticking forwards like swordfish or, like sailfish, they had tall dorsal fins, which they may have used to herd schooling fish while they hunted.

Among the pachycormids were filter-feeding giants. Leedsichthys was the biggest of them all, and the biggest bony fish ever to evolve, so far as we know. It grew to at least 16m (52ft), slightly longer than a London double-decker bus. 5 Fossils of these fish were first found in the late 19th century near Peterborough, England, by a farmer, Alfred Nicholson Leeds. Experts originally declared they were the back plates of a stegosaur, but later realised these were in fact the skull bones from a huge fish, which was named Leedsichthys problematicus, after the man who found them, and the puzzle of figuring out their true identity.

Until a few years ago, Leedsichthys was the only known filter-feeder from the whole of the Mesozoic era (between 252 and 66 million years ago). Splendid as it was, this giant had been consigned to an evolutionary footnote, a brief experiment in filter-feeding that existed for only a few million years. Recently, though, Matt Friedman from Oxford University led a team of palaeontologists that re-examined known fossils and discovered that Leedsichthys was not alone. There was in fact a succession of filter-feeding pachycormids that for at least 100 million years were roaming the oceans with their jaws wide open, sifting tiny animals from the water. Their disappearance at the end of the Cretaceous may have created the ecological space for the modern filter-feeding fish to rise to prominence.6

Nevertheless, it wasn’t simply the loss of big, conspicuous ray-finned fish like the pachycormids that once again rearranged the living systems of the seas. Other changes took place that paved the way for the rise of modern fish.

Not long ago, an important part of the story of what happened at the end of the Cretaceous was retrieved from the bottom of the sea. Networks of deep-sea drilling programmes have pulled long columns of sediment out of the seabed, far beneath the waves, at points dotted across the globe. These cores drill down hundreds of metres through layers of mud and silt that have accumulated over millions of years. Lodged inside the mud are minute fossils of fish teeth and scales that were scattered across the seabed when the animals died. These microfossils are much more widespread than fossils of whole animals; the odds are extremely slim of a body enduring the ordeals of deep time, of staying intact throughout the fossilisation process and not being crushed and bent out of shape. Teeth and scales are much more durable, and they’re also immensely abundant: there can be hundreds of them in a few grams of sediment. From these minute remains, bigger pictures can be drawn of the shifting, changing oceans.

At Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, Elizabeth Sibert and Richard Norris picked out thousands of microfossils from deep-sea cores. They assembled a timeline of teeth from ray-finned fish and denticles from sharks spanning 45 to 75 million years ago, and they discovered a distinct shift part-way through. In Late Cretaceous sediments more than half the microfossils were shark denticles. Then, at the beginning of the next geological period, the Palaeocene, teeth from ray-fins suddenly became more plentiful, outnumbering denticles by two or three times.

This change took place either side of a thin layer of the chemical element iridium, which is rare on Earth but common in meteorites. It’s thought this iridium layer was brought in by a gigantic meteorite that struck the Earth 66 million years ago, etching rocks worldwide with an indelible timestamp. Across this iridium boundary, ray-fin teeth not only became more abundant but also three times bigger, going from an average of one to three millimetres (0.04 to 0.1in). This doesn’t necessarily mean the fish themselves got bigger – some tiny fish have massive teeth and vice versa – but it’s a strong indication that fish were adapting to new ways of feeding, and expanding into new habitats.

In their 2015 study, Sibert and Norris go through various possible explanations for this lurch in the ratio of teeth to denticles. Maybe, for some reason, ray-fins simply started growing and shedding more teeth, but that doesn’t account for the increase in size. The view Sibert and Norris subscribe to is that 66 million years ago the oceans went through a wholesale transformation.

Before then, ray-fins were relatively rare in the pelagic realm and sharks dominated the gyres that swirled around the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. For millions of years, this situation seemed stable and unlikely to change. Sediment cores, in particular from the South Pacific, show a flatlining of the ratio of ray-fin teeth to shark denticles, right up to the iridium anomaly; then something jolted the system and the ray-fins quickly took over.

Sibert and Norris point to the mass extinction that brought the Cretaceous period to a close. The meteorite that laid down the iridium layer is at least partly to blame, worsened perhaps by massive volcanic activity that poured carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere. Dark skies loomed and acid seas spread, leaving behind a world vacated of much of its life. And just as in previous mass extinctions, new possibilities unfolded for the few survivors. This time, for some reason that isn’t yet fully understood, it wasn’t the sharks but the ray-finned fish that muscled their way into the abandoned waterways and flourished.

Previously, it had been well established from the fossil record that most of the major ray-finned fish groups alive today emerged over the last 50 to 100 million years. Some are known from the Cretaceous, like pufferfish, anglerfish and eels, and they were joined later by herring and sardines, minnows and carp, tuna, mackerel, flatfish and many more of the now super-abundant teleosts. The precise timing and the factors involved in the ray-fins’ rise to fame had been less clear. Now, this new view from the microfossils narrows things down and hints that the mass extinction played a pivotal role in filling the underwater world with the fish that we see today.

It might have been linked to the disappearance of ammonites and giant ocean-going reptiles, the plesiosaurs and mosasaurs, which were all extinct by the end of the Cretaceous. After they disappeared, ray-finned fish found themselves facing less competition for food and had fewer predators chasing after them.

A parallel story was unfolding at the same time on land. The disappearance of the dinosaurs set the scene for small, furry vertebrates to emerge from their nocturnal hiding places. So, it could be that if a giant meteor hadn’t happened to slam into the Earth the way it did 66 million years ago, the oceans, lakes, rivers and streams might not be brimming with so many thousands of fish species that wave their bony rayed fins, and similarly humans might not be here to watch and ponder them.

Persia, eighth century

The Book of Stones tells the story of a famous natural philosopher who set sail across the ocean to search for a doctor of the sea. He believed that inside the head of this magical fish was a yellow gemstone that could cure all maladies. The fish healed other sea creatures by rubbing its head on their wounds. And the gem also turned silver into gold, which was why the philosopher wanted one for himself.

For weeks the philosopher and his sailors searched and searched before they found a shoal of doctor fish. They cast their nets and caught one, but soon it transformed into a beautiful woman. She spoke a language no one understood and demonstrated her powers, healing the injuries and sickness of the crew. In time, one of the sailors fell in love with her, and she bore him a son who was human in every way except for his shining forehead. All the men thought she was happy living with them on the ship, but one night she escaped and dived into the sea, leaving her son behind.

The sailors continued on their way until they were hit by a dreadful storm. Enormous waves washed over the ship and the philosopher was sure the ship was doomed, until he spotted the strange woman, the Doctor of the sea, floating on the wild waves. The men begged her to help, and she transformed into a giant fish, opening her huge mouth and drinking the sea until the waves were calmed. Her son dived into the sea and followed after her down beneath the waves. When he returned to the ship next day, he too had a gleaming yellow gemstone in his head.

Notes

1 Imagine time was measured in distance, you set off on a walk into the past and at 100m (330ft) you reached the point when human divers started exploring the seas; to go back 380 million years, you’d have to walk to the moon.

2 Fossilised shark teeth also helped Nicolas Steno develop a theory for the formation of rocks from sediments piling up, with the oldest layers lower down and newer layers on top. This formed the foundations of stratigraphy, a major branch of geology that’s concerned with the layering of rocks.

3 Similar dead zones are seen in the parts of the ocean today that are overfed with nutrients, chiefly from farm runoff and sewage.

4 It used to be 65 million years ago, but dating updates tell us we need to add on a million years.

5 Previous estimates suggested Leedsichthys would have contended with the Blue Whale as the largest animal ever to evolve, at 30m (100ft) long. Recently, though, updated calculations based on incomplete fossil skeletons suggest they probably didn’t actually get that big, but at 16m (55ft) Leedsichthys would still have been by far the biggest teleost of all time, and the second biggest fish, bigger than your average Basking Shark (15m) and a little smaller than a Whale Shark (20m, 66ft).

6 Manta Rays and Whale Sharks first appeared in the late Palaeocene, roughly 60 million years ago, and Basking Sharks in the mid-Eocene, around 20 million years later.