brain rule

Make new friends but keep the old

The only thing you did to this sweet, calm little baby girl is to put a new toy in her crib. But she reacts as if you had just taken her favorite one away. Her eyes dart up at you and her face begins to contort, stress building up in her heart like a looming squall. She lets loose a Category 4 wail, flailing her legs and arching her back in nearly catastrophic distress. But it isn’t just you. This happens to the poor thing whenever a new experience comes her way: an unfamiliar voice, a strange smell, a loud noise. She is so sensitive. This infant simply falls apart whenever “normal” is disrupted.

A girl with long brown hair, about 15, is being asked about school and her extracurricular activities. As she starts to answer, you can tell something is wrong. She has the same troubled look on her face as the baby! She fidgets nonstop. She shakes her knee, twirls her hair, plays with her ear. Her answers come out in halting, constipated chunks. The girl doesn’t have very many activities outside of school, she says, though she plays the violin and writes a little. When the researcher asks her what is on her list of worries, she hesitates and then lets out the storm. Holding back tears, she says, “I feel really uncomfortable, especially if other people around me know what they’re doing. I’m always thinking, Should I go here? Should I go there? Am I in someone’s way?” She pauses, then cries, “How am I going to deal with the world when I’m grown? Or if I’m going to do anything that really means anything?” The emotion subsides, and she shrinks, defeated. “I can’t stop thinking about that,” she finishes, her voice trailing to a troubled whisper. The temperament is unmistakable. She’s that baby, 15 years later.

And she is clearly one unhappy child.

Researchers call her Baby 19, and she is famous in the world of developmental psychology. Through his work with her and others like her, psychologist Jerome Kagan discovered many of the things we know about temperament and the powerful role it plays in determining how happy a child ultimately becomes.

This chapter is all about why some kids, like Baby 19, are so unhappy—and other kids are not. (Indeed, most kids are just the opposite. Baby 19 is so named because babies 1 through 18 in Kagan’s study were comparatively pretty jolly.) We will discuss the biological basis of happy children, your chances of getting an anxious baby, whether happiness could be genetic, and the secret to a happy life. In the next chapter, we’ll talk about how you can create an environment conducive to your child’s happiness.

What is happy?

Parents often tell me their highest goal is to raise a happy child. When I ask what they mean, exactly, I get varying responses. Some parents mean happiness as an emotion: They want their children to regularly experience a positive subjective state. Some parents mean it more like a steady state of being: They want their children to be content, emotionally stable. Others seem to mean security or morality, praying that their child will land a good job and marry well, or be “upstanding.” Past a few quick examples, however, most parents find the notion hard to pin down.

Scientists do, too. One researcher who has spent many years trying to get at the answer is a delightful elf of a psychologist named Daniel Gilbert, at Harvard. Other definitions of happiness exist, of course, but Gilbert proposes these three:

• Emotional happiness. This is what most of the parents I ask probably mean. This type of happiness is, Gilbert wrote, “a feeling, an experience, a subjective state” untethered to something objective in the real world. Your child is delighted by the color blue, moved by a movie, thrilled by the Grand Canyon, satisfied by a glass of milk.

• Moral happiness. Intertwined with virtue, moral happiness is more akin to a philosophical suite of attitudes than to a spontaneous subjective feeling. If your child leads a good and proper life, filled with moral meaning, he or she might feel deeply satisfied and content. Gilbert uses the Greek word eudaimonia to describe the idea, a word Aristotle translated as “doing and living well.” Eudaimonia literally means “having a good guardian spirit.”

• Judgmental happiness. In this case, the word “happiness” is followed by words like “about” or “for” or “that.” Your child might be happy about going to the park. She might be happy for a friend who just got a dog. This involves making a judgment about the world, not in terms of some transient subjective feeling but as a source of potentially pleasurable feelings, past, present, or future.

Where does this happiness, regardless of type, come from? The main source of happiness was discovered by the oldest ongoing experiment in the history of modern American science.

The psychologist presiding over this research project is named George Vaillant. And he deserves it. Since 1937, researchers for the Harvard Study of Adult Development have exhaustively collected intimate data on several hundred people. The project usually goes by the moniker the Grant Study, named for the department store magnate W. T. Grant, who funded the initial work. The question they are investigating: Is there a formula for “the good life”? What, in other words, makes people happy?

Vaillant has been the project’s caretaker for more than four decades, the latest in a long line of scientific shepherds of the Grant Study. His interest is more than just professional. Vaillant himself is a self-described “disconnected” parent. Married multiple times, he has five children, one of whom is autistic and four of whom don’t speak to him very often. His own father committed suicide when he was 10, leaving him with few happy examples to follow. So he’s a good man to lead the search for happiness.

The project’s scientific godfathers, all of whom are now dead, recruited 268 Harvard undergraduates to the study. They were all white males, seemingly well-adjusted, several with bright futures ahead of them—including longtime Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee and President John F. Kennedy. Their lives were to be stretched out like a rack for years so that teams of professionals, including psychologists, anthropologists, social workers, even physiologists, could keep track of everything that happened to them. And that’s what they did.

With an initial thoroughness the Department of Homeland Security might envy, these men have endured exhaustive medical checkups every five years, patiently taken batteries of psychological tests, tolerated in-person interviews every 15 years, and returned questionnaires every other year, for nearly three-quarters of a century. Though supervised unevenly over the decades by what best might be called a tag team of researchers, the Grant Study is probably the most thorough research of its type ever attempted.

And what did they come up with after all these years? What in the end constitutes the good life? Consistently makes us happy? I’ll let Vaillant, in an interview with the Atlantic, speak for the group:

“The only thing that really matters in life [is] your relationships to other people.”

After nearly 75 years, the only consistent finding comes right out of It’s a Wonderful Life. Successful friendships, the messy bridges that connect friends and family, are what predict people’s happiness as they hurtle through life. Friendships are a better predictor than any other single variable. By the time a person reaches middle age, they are the only predictor. Says Jonathan Haidt, a researcher who has extensively studied the link between socialization and happiness: “Human beings are in some ways like bees. We have evolved to live in intensely social groups, and we don’t do as well when freed from hives.”

The more intimate the relationship, the better. A colleague of Vaillant’s showed that people don’t gain access to the top 10 percent of the happiness pile unless they are involved in a romantic relationship of some kind. Marriage is a big factor. About 40 percent of married adults describe themselves as “very happy,” whereas 23 percent of the never-marrieds do.

More research has since confirmed and extended these simple findings. In addition to satisfying relationships, other behaviors that predict happiness include:

• a steady dose of altruistic acts

• making lists of things for which you are grateful, which generates feelings of happiness in the short term

• cultivating a general “attitude of gratitude,” which generates feelings of happiness in the long term

• sharing novel experiences with a loved one

• deploying a ready “forgiveness reflex” when loved ones slight you

If those things sound obvious—the usual suspects in self-help magazines—this one may be a surprise: Money doesn’t make the cut. People who make more than $5 million a year are not appreciably happier than those who make $100,000 a year, the Journal of Happiness Studies found. Money increases happiness only when it lifts people out of poverty to about $50,000 a year in income. Past that, wealth and happiness part ways. This suggests something practical and relieving: Help your children get into a profession that can at least make around $50,000 a year. They don’t have to be millionaires to be thrilled with the life you prepare them for. After their basic needs are met, they just need some close friends and relatives. And sometimes even siblings, as the following story attests.

My brother is JOSH!

My two sons, ages 3 and 5, were running around a playground one cloudy Seattle morning. Josh and Noah were happily playing on swings, rolling on the ground, and shouting with other boys, everyone acting like the lion cubs-in-training they were. Suddenly, Noah was pulled to the ground by a couple of local bullies, large 4-year- olds. Josh bolted to his younger brother’s aid like a shot of Red Bull. Jumping between brother and bully, fists raised, Joshua growled through clenched teeth: “Nobody messes with my brother!” The shocked gang quickly scattered.

Noah was not only relieved but ecstatic. He hugged his older brother and ran around in circles, flooded with festive, excess energy. He inexplicably shot off lasers with make-believe sticks, shouting at the top of his lungs to anybody in earshot, “My brother is JOSH!” His good deed done, Joshua returned to his swing, grinning from ear to ear. It was an impressively joyous one-act show, applauded at length by our nanny, who was watching them. The essence of this story is the presence of happiness—generated by a close, intense relationship. Noah was clearly thrilled; Josh clearly satisfied. Sibling rivalry being what it is, such altruism is not the only behavior in which they regularly engage. But for the moment, these kids were well-adjusted and happy, observable in near-cinematic fashion.

Helping your child make friends

These findings about the importance of human relationships—in all their messy glory—greatly simplify our question about how to raise happy kids. You will need to teach your children how to socialize effectively—how to make friends, how to keep friends—if you want them to be happy.

As you might suspect, many ingredients go into creating socially smart children, too many to put into some behavioral Tupperware bowl. I’ve selected the two that have the strongest backing in the hard neurosciences. They are also two of the most predictive for social competency:

• emotional regulation

• our old friend, empathy

We’ll start with the first.

Emotional regulation: How nice

After decades of research burning through millions of dollars, scientists have uncovered this shocker of a fact: We are most likely to maintain deep, long-term relationships with people who are nice. Mom was right. Individuals who are thoughtful, kind, sensitive, outward focused, accommodating, and forgiving have deeper, more lasting friendships—and lower divorce rates—than people who are moody, impulsive, rude, self-centered, inflexible, and vindictive. A negative balance on this spreadsheet can greatly affect a person’s mental health, too, putting him at greater risk not only for fewer friends but for depression and anxiety disorders. Consistent with the Grant Study, those with emotional debits are some of the unhappiest people in the world.

Moody, rude, and impulsive sound an awful lot like faulty executive control, and that is part of the problem. But the deficit is even larger. These people are not regulating their emotions. To figure out what that means, we first need to answer a basic question:

What on earth is an emotion?

You can put this little vignette in the “Do as I say, not as I do” file:

Last night my son threw his pacifier. I was tired and frustrated and said, “We don’t throw things!” And then I threw it at him.

Perhaps the son did not want to go to sleep and in defiance threw the pacifier. Mom already told us she was tired and frustrated; you can probably add angry. Lots of emotions on display in these three short sentences. What exactly were they experiencing? You might be surprised by my answer. Scientists don’t actually know.

There is a great deal of argument in the research world about what exactly an emotion is. In part that’s because emotions aren’t at all distinct in the brain.

We often make a distinction between organized hard thinking, like doing a calculus problem, and disorganized, squishy emoting, like experiencing frustration or happiness. When you look at the wiring diagrams that make up the brain, however, the distinctions fade. There are regions that generate and process emotions, and there are regions that generate and process analytical cognitions, but they are incredibly interwoven. Dynamic, complex coalitions of networked neurons crackle off electrical signals to one another in highly integrated and astonishingly adaptive patterns. You can’t tell the difference between emotions and analyses.

For our purposes, a better approach is to ignore what an emotion is and instead focus on what an emotion does. Understanding that will point us to strategies for regulating emotions—one of our two main players in maintaining healthy friendships.

Emotions tag our world the way RoboCop tags bad guys

One of my favorite science fiction movies, RoboCop, has a great definition of emotions. The 1987 film takes place in a futuristic, crime-infested Detroit, a city then as now deeply in need of a hero. That hero turns out to be the cyborg RoboCop, a hybrid human formed from a deceased police officer (played by Peter Weller). RoboCop is unleashed onto the criminal underworld of the unsuspecting city, and he goes to work cleaning up the place. The cool thing is, RoboCop can apprehend bad guys while reducing collateral damage to anyone else. In one scene, he scans a landscape filled with criminals and innocent bystanders. You’re inside RoboCop’s visor; you can see him digitally tagging only the bad guys for further processing, leaving everyone else alone. Aim, fire: He blows away only the bad guys.

This kind of filtering is exactly what emotions do in the brain. You’re probably used to thinking of emotions as the same thing as feelings, but to the brain, they’re not. In the textbook definition, emotions are simply the activation of neurological circuits that prioritize our perceptual world into two categories: things we should pay attention to and things we can safely ignore. Feelings are the subjective psychological experiences that emerge from this activation.

See the similarity to the software in RoboCop’s visor? When we scan our world, we tag certain items for further processing and leave other items alone. Emotions are the tags. Another way to think of emotions is like Post-it notes that cause the brain to pay attention to something. Onto what do we place our little cognitive stickies? Our brains tag those inputs most immediately concerned with our survival—threats, sex, and patterns (things we think we’ve seen before). Since most people don’t put Post-it notes on everything, emotions help us prioritize our sensory inputs. We might see both the criminal pointing a gun at us and the lawn upon which the criminal stands. We don’t have an emotional reaction to the lawn. We have an emotional reaction to the gun. Emotions provide an important perceptual filtering ability, in the service of survival. They play a role in affixing our attention to things and in helping us make decisions. As you’d expect, a child’s ability to regulate emotions takes a while to develop.

Emotions are like Post-it notes, telling the brain to pay attention to something.

Why all the crying? It gets you to “tag” them

In the first few weeks after we brought our elder son home, all Josh seemed to do was cry, sleep, or emit disgusting things from his body. He’d wake up in the wee hours of the morning, crying. Sometimes I’d hold him, sometimes I’d lay him down; either one would only make him cry more. I had to wonder: Was this all he could do? Then I came home early from work one day. My wife had Josh in a stroller, and as I walked toward them both, Josh saw me and seemed to experience a sudden rush of recognition. He flashed me a megawatt smile that could have powered Las Vegas for an hour, then stared at me intently. I couldn’t believe it! I yelped and stretched out my arms to give him a hug. The noise was too loud, however, and the move too sudden. He instantly reverted to crying. Then he pooped his diapers. So much for variety.

My inability to decode Josh in his earliest weeks did not mean he—or any other baby—had a one-track emotion. A great deal of neurological activity occurs in both the cortex and limbic structures in all babies’ early weeks. We’ll take a look at these two brain structures in a few pages. By 6 months of age, a baby typically can experience surprise, disgust, happiness, sadness, anger, and fear. What babies don’t have are a lot of filters. Crying for many months remains the shortest, most efficient means of getting a parent to put a Post-it note on them. Parental attention is deep in the survival interests of the otherwise helpless infant, so babies cry when they are frightened, hungry, startled, overstimulated, lonely, or none of the above. That makes for a lot of crying.

Big feelings are confusing for little kids

Babies also can’t talk. Yet. They will—it is one of their first long-term, uniquely human goals—but their nonverbal communication systems won’t be connected to their verbal communication systems for quite some time. The ability to verbally label an emotion, which is a very important strategy for emotional regulation, isn’t there yet.

Until they acquire language, what’s in store for young children as their tiny, emotion-heavy brains stitch themselves together is lots of confusion. This struggle is especially poignant in the early toddler years. Young children may not be aware of the emotions they are experiencing. They may not yet understand the socially correct way to communicate them. The result is that your little one may act out in anger when he is actually sad, or she may just become grumpy for no apparent reason. Sometimes a single event will induce a mixture of emotions. These emotions and their attendant feelings can feel so big and so out of control that the kids become frightened on top of it, which only amplifies the effect.

Because kids often express their emotions indirectly, you need to consider the environmental context before you attempt to decode your child’s behavior. If you are concluding that parents need to pay a lot of attention to the emotional landscapes of their kids to understand their behavior—all to get them properly socialized—you are 100 percent correct.

Things eventually settle down. The brain structures responsible for processing and regulating emotions will wire themselves together, chatting like teenagers on their cell phones. The problem is that it doesn’t happen all at once. The job really isn’t finished until you and your child start applying for student loans. Though it takes a long time, establishing this communication flow is extremely important.

Once it matures, here’s what emotional regulation looks like: Suppose you are at a play with some friends, watching a moving scene from the musical Les Misérables. It’s the strangely powerful (some say sappy) song “Bring Him Home.” You know two things: (a) when you cry, you really sob, and (b) this scene can really skewer you. To save yourself from social humiliation, you reappraise the situation and attempt to suppress your tears. You succeed, barely. This overruling is emotional regulation. There is nothing wrong with crying, or any other number of expressions, but you realize that there are social contexts where certain behavior is appropriate and social contexts where it is not. People who do this well generally have lots of friends. If you want your kids to be happy, you will spend lots of time teaching them how and when this filtering should occur.

Where emotions happen in the brain

“It glows!” a little girl squealed in a mixture of delight and horror. “Ooh, I can see its claws!” said a little boy, just behind her. “And there’s its stinger!” said another girl, to which the boy replied, “Ooh. It looks just like your sister’s nose!” This was followed by some pushing. I laughed. We were on a field trip at a museum, and I was completely surrounded by a group of bubbling, lively third graders in awe of the way scorpions glow under a black light.

One of the most beautiful parts of this exhibit was also its focal point, a display just out of reach above their shoulders. Here was a large, lonely scorpion, motionless on a rock, sitting inside in a larger, lonelier fishbowl. Ultraviolet light shining from above, the animal looked just like a glow-in-the-dark Lord of the Arachnids. Or, if you are a brain scientist, one of the most complex structures in the brain—the ones that generate and process our emotions.

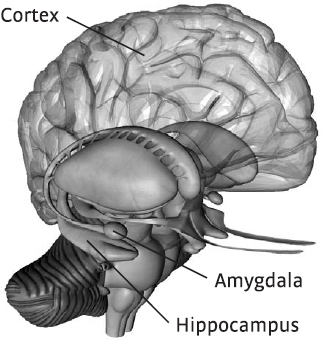

Picture, if you will, that same scorpion suspended in the middle of your brain. The brain has two lobes, or hemispheres, which can be likened to two fishbowls that have been partially fused together. I’ll describe the fishbowls first, the scorpion second.

The cortex: Senses and thinking

The partially fused fishbowls are the brain’s main hemispheres, logically called the left and right hemispheres. Each hemisphere is covered with a thick surface, made not of glass but a mixed layer of neurons and molecules. This cellular rind of tissue is the cortex. The cortex is only a few cells thick, and it is unlike the cortex of any other animal in the world. It is the tissue that makes us human. Among many other functions, ours is involved in abstract thinking (like doing algebra). It is also involved in processing external sensory information (like spotting a saber-toothed tiger). But we don’t feel threatened by either algebra or tigers because of the cortex. That’s the job of the scorpion.

The amygdala: Emotions and memories

This cerebral arachnid is part of a set of structures called the limbic system, which means “border” system. The scorpion’s claws, one for each hemisphere, are called amygdala, which for good reason means “almond” (that’s what they look like). The amygdala helps to generate emotions and then store memories of the emotions it generates. In the real world of the brain, you would not see the scorpion shape. The limbic regions are obscured by other structures, including an impenetrable thicket of cellular connections dangling down from every millimeter of the fishbowl’s surface. But the amygdala is not connected just to your cortex. It is connected to regions that regulate your heartbeat, your lungs, and areas that control your ability to move. Emotions really are distributed among assemblies of cells scattered throughout the brain.

Still with me? Things are about to get more complex.

What a gossip!

The central region of the amygdala possesses big, fat connections to an area of the brain called the insula, a smallish region near the middle of the organ. That’s an important finding. The insula, with assistance from its amygdalar buddy, helps create subjective, emotionally relevant contexts for the sensory information arising throughout the body from our eyes, ears, nose, fingertips, and more. How does that occur? We haven’t the foggiest idea. We know the insula collates perceptions of temperature, muscle tension, itch, tickle, sensual touch, pain, stomach pH, intestinal tension, and hunger from the rest of the body. And then it chats about what it finds with the amygdala. Some researchers believe this communication is one of the reasons gathering information south of the head is so important to the creation and perception of emotional states. It may be involved in certain mental illnesses, like anorexia nervosa.

You get the impression this scorpion does a lot of talking. These connections are the phone lines allowing this part of the brain—and indirectly just about everywhere else in the body—to hear what the rest of the brain says. This is a big hint that emotion functions are distributed all over the brain, or at least announced all over the brain.

How the amygdala learns to brew up emotions and why it needs so many other neural regions to assist it are to some degree a mystery. We know the brain takes its own sweet time getting these connections wired up to one another—years, in some cases. Ever watched a selfish little boy blossom into a thoughtful young man? All it takes is a little time, sometimes.

Empathy: The glue of relationships

Along with the ability to regulate emotions, the ability to perceive the needs of another person and respond with empathy plays a huge role in your child’s social competence. Empathy makes good friends. To have empathy, your child must cultivate the ability to peer inside the psychological interiors of someone else, accurately comprehend that person’s behavioral reward and punishment systems, and then respond with kindness and understanding. The outward push of empathy helps cement people to each other, providing a long-term stability to their interactions. See what happens between mother and daughter in this story:

I have GOT to learn not to be so crude when I get home. I was bitching to Shellie on the phone after work [about] how much of a pain in the butt my boss is. A few minutes later I smelled diaper rash cream, then felt some one trying to lift up my skirt. My dear two-year-old daughter had opened a tube of Desitin and was trying to smear it on my backside! I said “What in the world are you doing?” She said, “Nothing Mommy. It’s for the pain in your butt.” I love this girl so much. I could have squeezed her til she burst!

Notice what the daughter’s creative empathy did for her mom’s attitude toward their relationship. It seemed to bind them together. These empathetic interactions have names. When one person is truly happy for another, or sad for another, we say they are engaging in active-constructive behaviors. These behaviors are so powerful, they can keep not only parents and children together but husbands and wives together. We talked in the Relationship chapter about the role of empathy in the transition to parenthood. If your marriage has a three-to-one ratio of active-constructive versus toxic-conflict interactions, your relationship is nearly divorce-proof. The best marriages have a ratio of five to one.

Mirror neurons: I feel you

There is a neurobiology behind empathy, and I was reminded of it the first time my younger son got a shot. As the doctor filled the syringe, my wary eyes followed his movements. Little Noah, sensing something was wrong, began wriggling in my arms. He was getting ready to receive his first set of vaccinations, and he already didn’t like it. I knew the next few minutes were going to be excruciating. My wife sat this one out in the waiting room, having endured the process with our elder child and being no friend of the needle herself (when she was a little girl, her pediatrician’s nurse actually had Parkinson’s). It was up to me to hold Noah firmly in my arms to keep him still while the doctor did the dirty work. That shouldn’t have been a big deal. I have a familiar research relationship with needles. In my career I have injected mice with pathogens, neural tissues with glass electrodes, and plastic test tubes with dyes, sometimes missing the tube but not my finger. But this time was different. Noah’s eyes locked onto mine as the needle pushed into his little arm like a metallic mosquito from hell. Nothing prepared me for the look of betrayal on my youngest son’s face. His forehead wrinkled like cellophane. He howled. I did too, silently. For no rational reason, I felt like a failure. My arm even ached.

Blame it on my brain. As I witnessed the pain in Noah’s arm, some researchers believe, neurons that mediate the ability to experience the pain in my arm were suddenly springing to life. I was not getting the shot, but that didn’t matter to my brain. I was mirroring the event, literally experiencing the pain of someone about whom I care a great deal. No wonder my arm ached.

These so-called mirror neurons are scattered across the brain like tiny cellular asteroids. We recruit them, in concert with memory systems and emotional processing regions, when we encounter another person’s experiences. Neurons with mirrorlike properties come in many forms, researchers think. In my case, I was experiencing the mirrors most closely associated with extremity pain. I was also activating motor neurons that governed my arm’s desire to withdraw from a painful situation.

Many other mammals appear to have mirror neurons, too. In fact, mirror neurons initially were discovered by Italian researchers trying to figure out how monkeys picked up raisins. The researchers noticed that certain brain regions became activated not only when monkeys picked up raisins but also when they simply watched others pick up raisins. The animals’ brains “mirrored” the behavior. In humans, the same neural regions are activated not only when you tear a piece of paper and when you see Aunt Martha tearing a piece of paper—but also if you hear the words “Aunt Martha is tearing a piece of paper.”

It’s like having a direct internal link to another person’s psychological experience. Mirror neurons permit you to understand an observed action by experiencing it firsthand, even though you’re not. Sounds a lot like empathy. Mirror neurons may also be profoundly involved in both the ability to interpret nonverbal cues, particularly facial expressions, and the ability to understand someone else’s intentions. This second talent falls under an umbrella of skills called Theory of Mind, which we’ll describe in detail in the Moral chapter. Some researchers think Theory of Mind skills are the engines behind empathy.

Not all scientists agree about the role mirror neurons play in mediating complex human behaviors like empathy and Theory of Mind. It is definitely a matter of contention. The preponderance of evidence suggests a role for them, but I also think a great deal more research needs to be done. With more research, we may find that empathy is not a touchy-feely phenomenon but, rather, has deep neurophysiological roots. That would be an astonishing thing to say.

An uneven talent

Because this type of neural activity easily can be measured, it is possible to ask if every child has an equal talent for empathy. The unsurprising answer is no. Autistic children, for example, have no ability to detect changes in people’s emotional states. They simply can’t decode another person’s psychological interiors by looking at his or her face. They cannot divine people’s motivations or predict their intentions. Some researchers think they lack mirror-neuron activity.

Even outside of this extreme, empathy is uneven. You probably know people who are naturally highly empathetic and others with the emotional understanding of dirt. Are they born that way? Though separating social and cultural influences is tough, the equally tough answer is: probably.

This neural hardwiring suggests that there are aspects of a kid’s social skill set a parent just can’t control. It’s a big thing to say, but there may be a genetic component to the level of happiness your offspring can achieve. This somewhat scary idea deserves a more detailed explanation.

Could happiness or sadness be genetic?

My mother says I was born laughing. Even though I entered the world prior to video cameras—or dads—in the delivery room, I do have a way to independently verify this observation. The pediatrician supervising my birth left a note, which my mother kept and I still have. The note says: “Baby appears to be laughing.”

That’s funny, for I love to laugh. I’m also an optimist. I tend to believe things will work out just fine, even when no shred of evidence warrants the attitude. My glass will always be half-full, even if the glass is leaking. This predisposition has probably saved my emotional bacon more than once, given the number of years I have dealt with the often-depressing genetics of psychiatric disorders. If I was born laughing, was I also born happy? No, of course not. Most babies are born crying, and it doesn’t mean they are born depressed.

But is a tendency toward happiness or sadness genetic? Researcher Marty Seligman, one of the most well-regarded psychologists of the 20th century, thinks so. Seligman was among the first to directly link stress with clinical depression. His previous research involved shocking dogs to the point of learned helplessness; perhaps in reaction to that, many years ago he switched gears. His new topic? Learned optimism.

The happiness thermostat

After years of researching optimism, Seligman concluded that everyone comes into this world with a happiness “set point,” something akin to a behavioral thermostat that allows us to experience happiness within a certain behavioral range. This notion is based on the ideas of the late David Lykken, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Minnesota. Some children’s set points are programmed to high; they are naturally happy regardless of the circumstances life throws at them. Some children’s set points are programmed to low. They are by nature depressive, regardless of the circumstances life throws at them. Everybody else is in the middle.

This might sound a bit deterministic, and it is—sort of. Seligman is quick to caution us that what happiness you consistently experience also has nurture components. He even has a formula, the Happiness Equation, to measure how happy people are. It is the sum of that set point, plus certain circumstances in your life, plus factors under your voluntary control.

Not everybody agrees with Seligman; the Happiness Equation has elicited special criticism. A preponderance of evidence suggests there is something to this set-point idea, but it needs work. To date, no neurological regions have been found devoted exclusively to the thermostat. Or to being happy in general. At the molecular level, researchers have yet to isolate a “happiness” gene or its thermostatic regulators, though researchers are working on both. We’ll take a closer look at these genes at the end of the chapter.

All of this work—starting with Baby 19, the distressed girl at the beginning of this chapter—suggests that genetic influences play an active role in our ability to experience sustained happiness.

Born with a temperament

Parents have known for centuries that babies come to this world with an inborn temperament. Scientist Jerome Kagan, who studied Baby 19, was the first to prove it. Human temperament is a complex, multidimensional concept—a child’s characteristic way of responding emotionally and behaviorally to external events. These responses are fairly fixed and innate; you can observe them in your baby soon after he or she is born. Parents often confuse temperament with personality, but from a research perspective they aren’t the same thing. Experimental psychologists often describe personality in much more mutable terms, as behavior shaped primarily by parental and cultural factors. Personality is influenced by temperament the same way a house is influenced by its foundation. Many researchers think temperament provides the emotional and behavioral building blocks upon which personalities are constructed.

High reactives vs. low reactives

Kagan was interested in one layer of temperament: how babies reacted when exposed to new things. He noticed that most babies took new things in stride, gazing calmly at new toys, curious and attentive to new inputs. But some babies were much edgier, more irritable. Kagan wanted to find a few of these more sensitive souls and follow them as they grew up. Babies 1 through 18 fit the first model just fine. These calm babies are said to have low-reactive temperaments. Baby 19 was completely different. She, and babies like her, have high-reactive temperaments.

The behavior remains remarkably stable over time, as Kagan found in his most well-known experiment. The study is still ongoing, having survived even the old sage’s retirement (a colleague has taken it over). The experiment enrolled 500 kids, starting at 4 months of age, who were coded for low reactivity or high reactivity. He retested these same kids at ages 4, 7, 11 and 15; some beyond that. Kagan found that babies coded as highly reactive were four times more likely than controls to be behaviorally inhibited by age 4, exhibiting classic Baby 19 behavior. By age 7, half of these kids had developed some form of anxiety, compared with 10 percent of the controls. There is almost no crossover. In another study of 400 kids, only 3 percent switched behaviors after five years. Kagan calls this the long shadow of temperament.

Will you get an anxious baby?

A researcher friend of mine has two little girls, ages 6 and 9 as of this writing, and their temperaments could not be more Kaganesque. The 6-year-old is little Miss Sunshine, socially fearless, prone to taking risks, ebullient, confident. She will charge into a playroom full of strangers, initiate two conversations at once, quickly survey all of the toys in the room, and then lock down on the dolls, playing for hours. Her big sister is the opposite. She seems fearful and tentative, cautiously tiptoeing into the same playroom after only reluctantly leaving her mother’s side. She then finds some safe corner and sits there. She shows no interest in exploring, hardly speaks at all, and appears scared if somebody tries to talk to her. My friends have their own Baby 19.

Will you have one, too? You stand a one-in-five chance. High reactives composed about 20 percent of the population in Kagan’s studies. But how a highly reactive baby turns out depends on many things. Every brain is wired differently, so not every brain state sparks the same behavior. That’s an important point. On top of that, high vs. low reactivity is only one dimension of temperament. Researchers look at everything from types of distress to attention span to sociability to activity level to the regularity of bodily functions. Studies like Kagan’s make conclusions about tendencies, not destinies. The data do not forecast what these children will become so much as they predict what they will NOT become. Highly reactive infants will not grow up to be exuberant, outgoing, bubbly, or bold. The older daughter will never become the younger daughter.

And if your infant is highly reactive? She might seem hard to parent, but there’s a silver lining. As these highly reactive children navigated through school, Kagan noticed, most were academically successful, even if they were a bucket of nerves. They made lots of friends. They were less likely to experiment with drugs, get pregnant, or drive recklessly. We think that’s because of an anxiety-driven need to acquire compensatory mechanisms. Kagan regularly employed high reactives during his research career. “I always look for high reactives,” he told the New York Times. “They’re compulsive, and they don’t make errors; they’re careful when they’re coding data.”

Why are fussy babies later the most likely to comply with parental wishes, be better socialized, and get the best grades? Because they are the most sensitive to their environments, even if they snarl about being guided all the way. As long as you play an active, loving role in shaping behavior, even the most emotionally finicky among us will grow up well.

So you can see temperament at birth, and it remains stable over time. Does that mean temperament is completely controlled by genes? Hardly. As we saw with the ice-storm children in the Pregnancy chapter, it is possible to create a stressed baby simply by increasing the mother’s stress hormones—not a double helix in sight. The involvement of genes is a scientific question, not a scientific fact. Happily, it is being researched.

Studies of twins so far show that there is no one gene responsible for temperament. (Gene work almost always begins with twins, the gold standard being twins separated at birth and raised in different households.) When you look at the temperaments of identical twins, the degree of resemblance, the correlation, is about 0.4. This means there is probably some genetic contribution, but it is not a slam dunk. For fraternal twins and non-twin siblings, the correlation is between 0.15 and 0.18, even less of a slam dunk.

Studies suggest that fussy babies are later more likely to comply with your wishes, be better socialized, and get better grades.

But a few genes have been isolated that might help explain one of the most baffling phenomena in all of developmental psychology: the resilient kid.

How can a kid go through all that and turn out OK?

The civil war that gave rise to South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, also generated the so-called Lost Boys of Sudan. Their story is familiar.

Families experienced unbelievable suffering during the war, resulting in the untethering of 20,000 young boys from their homes. Sometimes the untethering was deliberate: families encouraged sons to leave home, fearful they would be conscripted into soldiery. Sometimes their parents were killed. These kids wandered around a war zone with no visible means of support, sometimes for years. Many died—from disease, wild animals, crime. The last thing you’d think is that one of these boys would graduate from Michigan State University with a master’s degree in public health, and then return to Sudan to open up a health clinic.

Yet that is exactly what happened to Jacob Atem. Atem made it to Ethiopia and then a refugee camp in Kenya. At age 15, he was among a group of Lost Boys resettled in the United States. Atem later returned to Sudan to build a clinic that treats 100 patients a day. How could someone be so resilient after living through such violence? What not only kept Jacob from wilting but drove him to then become a force for good? Joan Hecht, who created the Alliance for the Lost Boys of Sudan, has an idea. The New York Times quoted Hecht in a story about Atem: “[S]o many of them had ‘an inner strength and inner faith and inner drive to succeed,’ motivated ‘to bring pride and dignity to their family’s name.’ That same impulse, [Hecht] said, pushed many of them to leave the safety and comfort of the United States and return to their homeland to try to help.”

How do we explain people like Jacob? The short answer is that we can’t. Many kids are severely traumatized by abusive experiences. But not all. Kids like Jacob have an almost supernatural ability to rise above their circumstances. Researchers have spent entire careers trying to uncover the secrets of this resiliency. Geneticists recently have joined in, and their surprising results represent the cutting edge of behavioral research today.

Three resiliency genes

Human behavior is almost always governed by the concerted teamwork of hundreds of genes. Nonetheless, as with any team sport, there are dominant players and minor ones. Though this work is at best preliminary, here are three genetic franchise players worth keeping an eye on. They may have a role in shaping the temperament and personality of our children.

Slow MAOA: Lessoning the pain of a trauma

Children who are sexually abused are at a much higher risk for becoming alcoholics—a fact researchers have known for years. They also are at greater risk for developing a debilitating mental-health issue called antisocial personality disorder. But this is decidedly not true if the child has a variant of a gene called MAOA, which stands for monoamine oxidase A. There are two versions of this gene, one we’ll call “slow” and the other “fast.” If the child has the slow version, she is surprisingly immune to the debilitating effects of her childhood. If she has the fast version, she falls into the stereotype. The fast version of this gene assists in hyper-stimulating the hippocampus and parts of the amygdala when a traumatic memory is remembered. The pain is too great; Jack Daniels is often turned to for relief. The slow version of this gene calms these systems remarkably. The traumas are there, but they lose their sting.

DRD4-7: A guard against insecurity

Children who grow up without parental support, or children who have cold and distant parents, often feel deeply insecure and act out in an effort to gain attention. The behavior is both understandable and obnoxious. But not all kids who have such mothers have this insecurity, and a group of researchers in the Netherlands think they know why. A gene called DRD4, which stands for dopamine receptor D4, is deeply involved. It is one of a family of molecules capable of binding to the neurotransmitter dopamine and exerting specific physiological effects. If children have a variation of this gene called DRD4-7, this insecurity never develops. It’s as if the gene product coats the brain in Teflon. Kids without this variant have no such protection from the effects of insensitive parents; for kids who do, the increase is sixfold.

Researchers have known for years that some adults react to stressful, traumatic situations by taking them in stride. They may be debilitated for a while, but they eventually show solid signs of recovery. Other adults in the same situations experience deep depression and anxiety disorders, showing no signs of recovery after a few months. Some even commit suicide. These twin reactions are like grown-up versions of Kagan’s low-reactive and high-reactive infants.

The gene 5-HTT, a serotonin transporter gene, may partially explain the difference. As the name suggests, the protein encoded by this gene acts like a semitruck, transporting the neurotransmitter serotonin to various regions of the brain. It comes in two forms, which I’ll term “long” and “short” variants.

If you have the long form of this gene, you are in good shape. Your stress reactions, depending upon the severity and duration of the trauma, are in the “typical” range. Your risk for suicide is low and your chance at recovery high. If you have the short form of this gene, your risk for negative reactions, such as depression and longer recovery times, in the face of trauma is high. Interestingly, patients with this short variation also have difficulty regulating their emotions and don’t socialize very well. Though the link has not been established, this sounds like Baby 19.

There really do appear to be children who are born stress-sensitive and children who are born stress-resistant. That we can in part tie this to a DNA sequence means that we can responsibly say it has a genetic basis. Which means that you could no more change this influence on your child’s behavior than you could change her eye color.

Tendencies, not destinies

Take this genetic discussion with a boulder of salt. Some of these DNA-based findings require much more research to tie up important loose ends before we can label them as true. Some need to be replicated a few more times to be convincing. All show associations, not causations. Remember: Tendency is NOT destiny. Nurturing environments cast a large shadow over all of these chromosomes, a subject we will take up in the next chapter. Yet DNA deserves a place at the behavioral table, even if it’s not always at the head, because the implications for moms and dads are staggering.

In the brave new world of medicine, genetic screens for these behaviors probably will become available to parents. Would it be valuable to know if your new baby is high or low reactive? A child who is vulnerable to stress would obviously need to be parented differently from one who is not. One day your pediatrician may be able to give you this information based on something as simple as a blood test. Such a test is far off in the future. For now, understanding your child’s seeds of happiness will have to come from getting to know your child.

![]()

Key points

• The single best predictor of happiness? Having friends.

• Children who learn to regulate their emotions have deeper friendships than those who don’t.

• No single area of the brain processes all emotions. Widely distributed neural networks play critical roles.

• Emotions are incredibly important to the brain. They act like Post-it notes, helping the brain identify, filter, and prioritize.

• There may be a genetic component to how happy your child can become.

reminder: references at www.brainrules.net/references