Vesturland

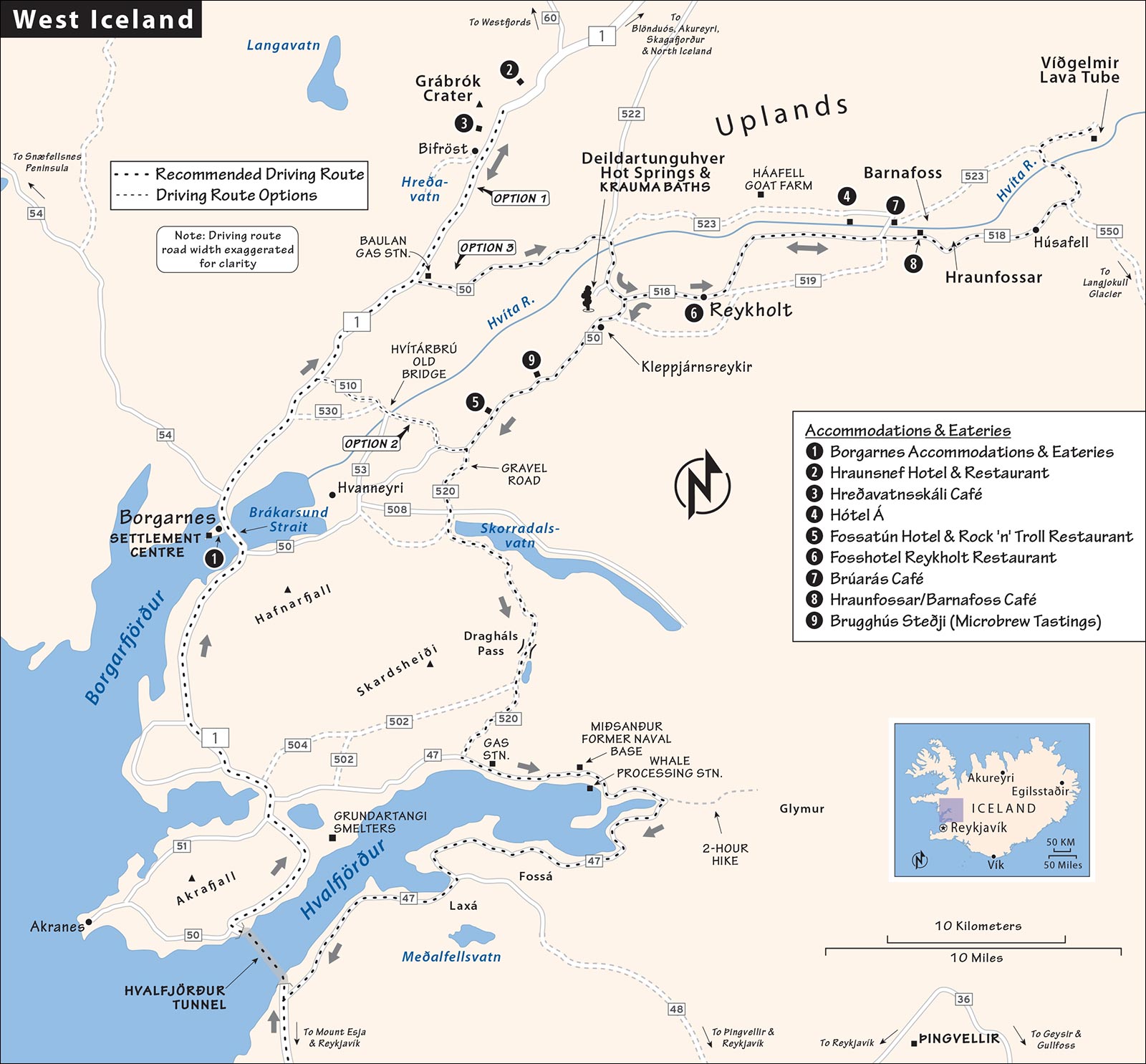

To round out your look at Iceland without straying too far from the capital region, head north from Reykjavík to West Iceland (Vesturland). A day trip here is more low-key than to the Golden Circle or the South Coast. The area is farming country—more sedate, thinly settled, and a bit more refined. There are fewer tourists, partly because the sights are less spectacular. But there are definitely some exciting natural wonders, as well as enjoyable attractions for those with a healthy interest in the early Icelandic sagas. And if you’re heading around the Ring Road, you’ll pass through this area regardless; consider pausing to take in the sights.

The heart of the region, called Borgarfjörður (BOR-gar-FYUR-thur), stretches from the waters of its namesake estuary up past thousand-year-old lava flows to Iceland’s second-largest glacier, Langjökull. I’ve organized this chapter into four sections: a driving tour of the region; Borgarnes, the main town, with a striking setting on a peninsula in the middle of the fjord; a hike up the volcanic Grábrók crater; and the area around Reykholt, with sights and accommodations scattered across a broad valley a 45-minute drive east of Borgarnes.

As a Day Trip: You can visit West Iceland on your own by car (following the driving tour outlined in this chapter), or with a bus excursion. The major excursion bus companies offer day trips to the Víðgelmir lava-tube cave that include some, but not all, of the sights listed in this chapter (see list of tour companies on here).

As an Overnight: Accommodations in this area tend to be reasonably priced. In this chapter, I recommend staying in one of three areas: in Borgarnes, near Grábrók crater, or in and near Reykholt.

Sleeping here is particularly smart if you’re continuing farther north along the Ring Road and want to see the region in depth. Some people stay in West Iceland on their first night in Iceland—bypassing Reykjavík and getting a head start on their trip around the Ring. (Borgarnes is less than two hours’ drive from Keflavík Airport.)

Name Note: Pay attention if you are using GPS to navigate: Iceland has two towns that go by the name of Reykholt—one here in West Iceland, and the other about 100 miles away, near the Golden Circle.

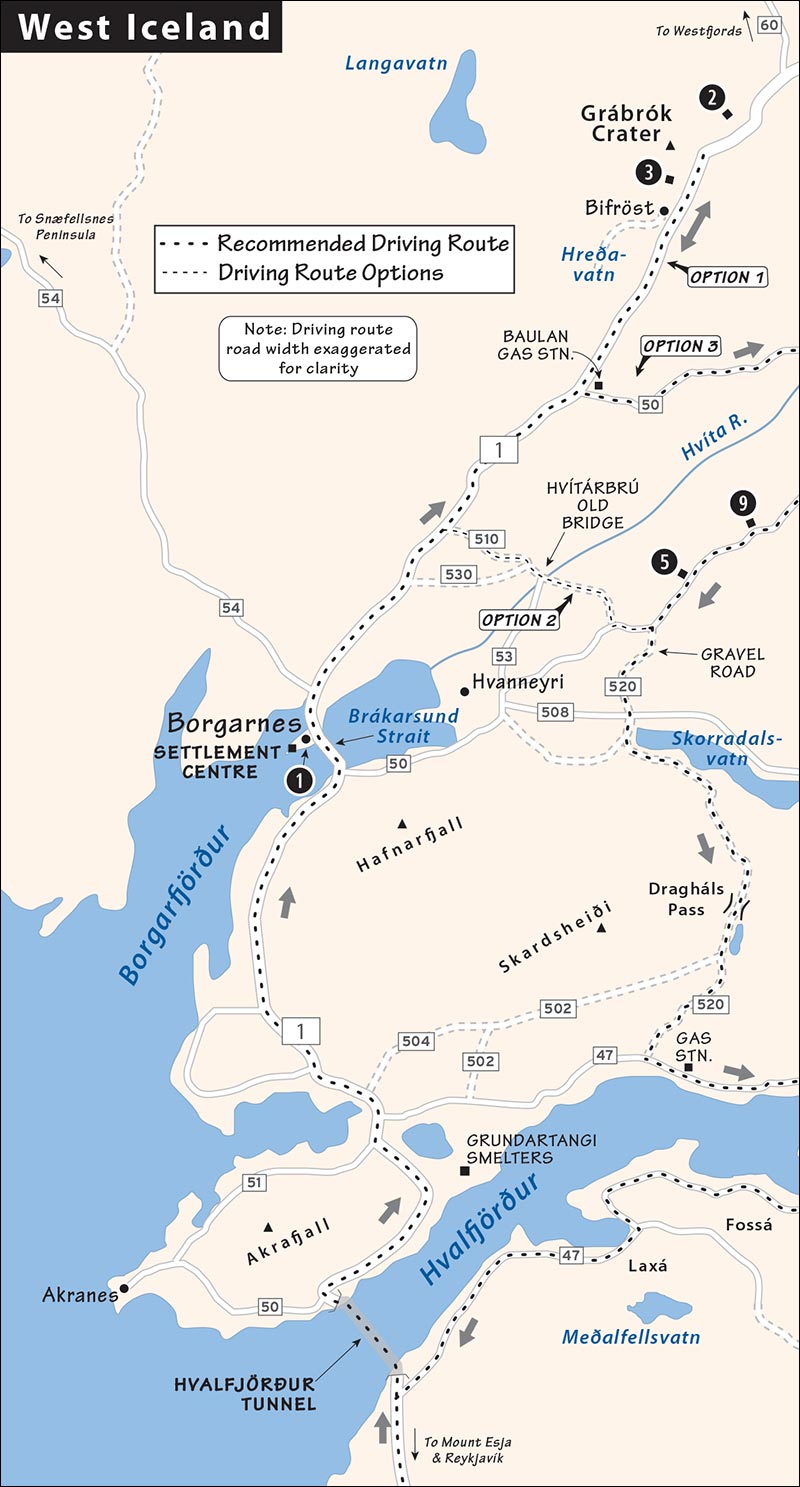

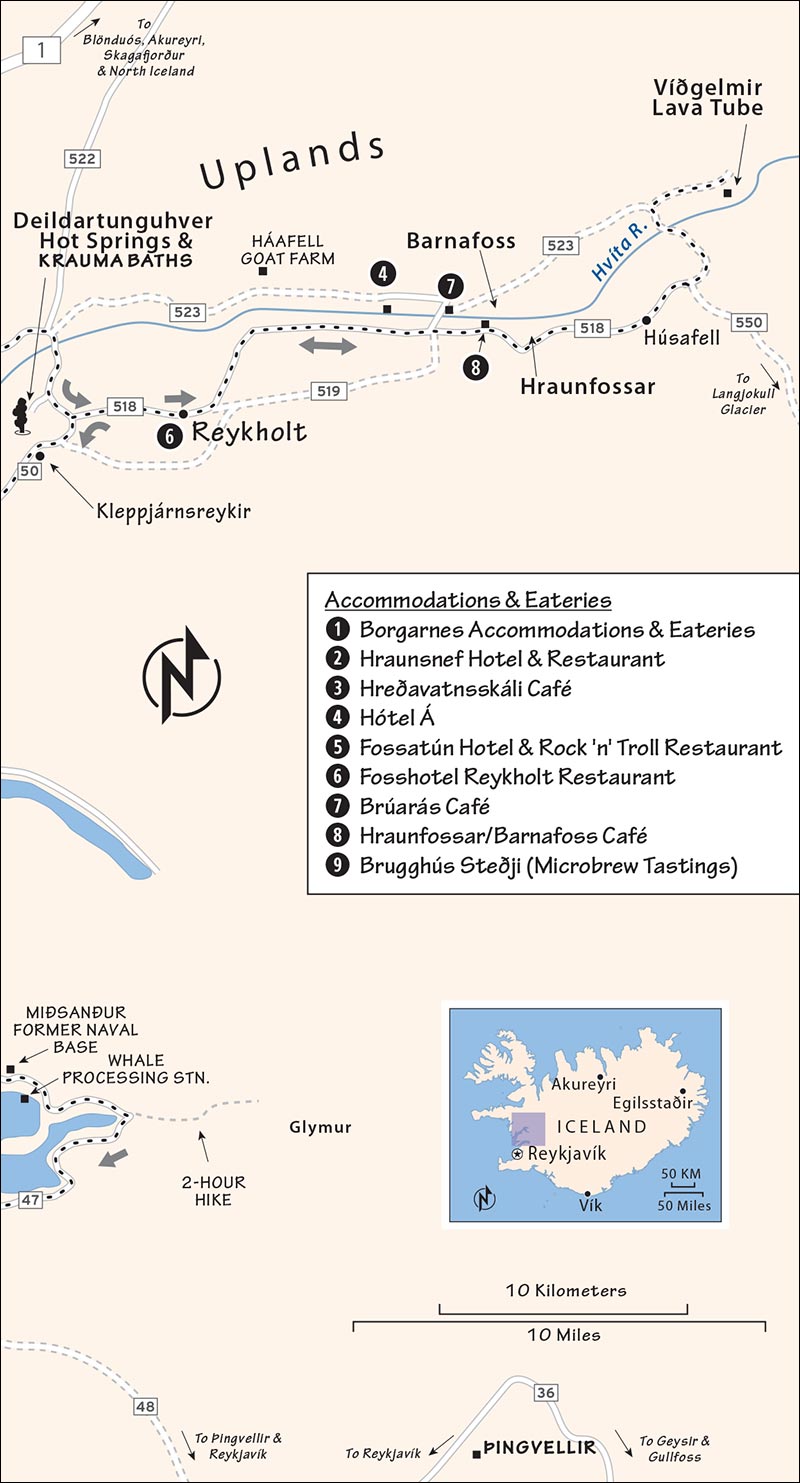

This self-guided itinerary assumes you’re seeing West Iceland’s highlights as a day trip from Reykjavík. Budget about 10 hours (about half of that is driving). Start by driving an hour along highway 1 to the town of Borgarnes for some sightseeing, detour up to Grábrók crater, then continue over to the area around Reykholt, where you’ll do a circuit of the area’s sights, before heading back to Reykjavík along highways 520 and 47 (a slower but more scenic return).

The following plan is minimalistic; it assumes that you’ll just visit the town of Borgarnes, Grábrók crater, and a few easy sights in and around Reykholt. To adjust this plan, see the tips on the next page.

Other Sights in the Area: There’s plenty more to see beyond my suggested plan above. You can mix and match, depending on your interests, and the weather and road conditions. Historians can focus on the good museums in Borgarnes as well as the modestly interesting church complex at Reykholt. Outdoorsy travelers can spelunk through an underground lava-tube cave at Víðgelmir (it’s best to book ahead). Hot-spring enthusiasts may want to check out the new premium thermal bath (Krauma) at Deildartunguhver. Families can add a visit to the Háafell Goat Farm (fun for kids and livestock lovers). Note: To add more sights—especially the Víðgelmir lava tube—you’ll need to set out earlier, return later, skip something else, or stay overnight. You can shave off a half-hour by returning on highway 1 instead of the scenic route.

Doing the Route in Reverse: It’s worth considering driving the route in the reverse direction from what I’ve described. Indoor sights here open at 10:00; if you’re getting an early start (i.e., leaving Reykjavík around 8:00), you might as well take the scenic route on your way up, while you’re fresh.

Weather and Road Conditions: As elsewhere in Iceland, check the weather forecast and road conditions before you head out—strong winds occasionally close highway 1 between Reykjavík and Borgarnes. Note that the scenic route from the Reykholt area back to Reykjavík (highways 520/47) is more difficult to drive, with long stretches curling around dramatic fjords, and short stretches on rough, unpaved roads—including one over a low mountain pass. Faint-hearted drivers should stick to highway 1. Before you go, double-check road conditions at Road.is.

This section outlines the driving directions and various route options for your West Iceland drive. Recommended sights, restaurants, and hotels along this driving route are described later in the chapter.

This route takes you north via highway 1 and the Hvalfjörður tunnel. It’s a bit over an hour’s drive to Borgarnes.

• Leave Reykjavík on highway 1 to the north, following signs for Borgarnes, Akureyri, and 1n.

As you leave the city, you pass under Esja, the mountain that shadows the city to the north, and you’ll see the parking lot for hikers climbing the peak. As you round the mountain, you’ll see some of the city’s chicken hatcheries to your left. A little farther on, an intriguing stone structure is actually just the retaining wall for a pig farm. You’ll pass Kjalarnes, a small suburban community. Strong winds are frequent along the road here. Soon after, you’ll enter the two-lane, 3.5-mile-long tunnel that passes beneath the fjord. (If you prefer to take the scenic route around the fjord—highways 47 and 520—on your way up, turn off on the right just before the tunnel entrance.)

Finished in 1998, Hvalfjörður tunnel cut the travel time from Reykjavík to Borgarnes and Akureyri by almost two hours. Before that, you had to drive all the way around the fjord (on what is now highway 47). While the tunnel area is not actively volcanic, the undersea rock is warm (up to 135°F near its south end). If your car’s controls show the outside temperature, notice how the south end of the tunnel is several degrees warmer than the north end. Watch your speed in the tunnel: The speed limit is 70 km/h, and monitored by cameras. You’ll pay the tunnel toll on the north side, as you exit (1,000 ISK; for tunnel info see www.spolur.is).

• At the roundabout just after the tunnel, go right, continuing to follow signs for Borgarnes and Akureyri. (Going left would bring you to Akranes, a relatively large but skippable town of 6,000 people, many of whom work in the fish processing industry or in the nearby metal smelters.)

In a few minutes, you’ll pass two huge metal smelters at Grundartangi. The green-and-brown one produces ferrosilicon, the blue one aluminum. A third smelter, producing silicon for the solar power industry, may be operational by the time of your visit. Smelters need to be along the coast, as ships bring in the raw ore (such as bauxite for making aluminum) and carry the finished product to market. This is an efficient way of putting Iceland’s electricity surplus to use, and the smelters do create jobs (though they require a relatively small crew).

You’ll now cross a low-lying, thinly settled plain between two mountains: Akrafjall on your left, and Hafnarfjall (HAHP-nahr-FYAHTL) to your right. On a clear day, you might be able to see the mountains of the Snæfellsnes Peninsula far ahead of you. Farther right past Hafnarfjall is another mountain, Skarðsheiði, which under snow cover looks like a meringue chopped into great wavy peaks.

The road curls around the left side of Hafnarfjall; this stretch is subject to frequent high winds. Soon you’re driving along the base of vast gravel slopes that tumble down from Hafnarfjall. You’ll see many small islands in Borgarfjörður, the fjord to your left.

Eventually the town of Borgarnes will come into view, and the road will bend left and cross a causeway and bridge into the town.

When you’re ready to continue toward the Reykholt area, you have three options: In good weather, hikers will want to head up to the Grábrók volcanic crater, then loop back down toward Reykholt. (All together, Grábrók adds about 1.5 hours, including the drive and time to hike up to the crater, but not lunch.) If the weather’s too cold or windy to hike to the crater, you could skip Grábrók and take the scenic route to the Reykholt area over the old bridge called Hvitárbrú. Or take the quicker route through Baulan.

Each of these options takes you to Deildartunguhver hot springs—the first of the Reykholt-area sights described later in this chapter. Notice that no single route connects all of your choices in the Reykholt area; you’ll make one or more loops to connect them, via paved highway 518 and unpaved highways 519, 523, and 550. The recommended Brúarás Café, more or less at the center of the Reykholt sights, is a great all-purpose stop for a snack, drink, or meal; they’re also happy to answer questions about this area.

For any of these, you’ll begin by heading north from Borgarnes on highway 1, following signs toward Akureyri.

Option 1, Recommended Detour to Grábrók Crater (50 minutes): From Borgarnes, head up highway 1 about 30 minutes; you can’t miss the crater, on the left side of the road. After visiting, return south and backtrack on highway 1 about 10 minutes; look for a small ÓB gas station (called Baulan). Turn left here onto highway 50, then drive another 15 minutes until you see a small turnoff to the right marked Deildartunguhver. (If you get to the junction with highway 518, you’ve gone a half-mile too far.)

Option 2, Skipping Grábrók, via Hvitárbrú Bridge (40 minutes): This pleasant route crosses bridges that don’t allow trucks or buses. From Borgarnes, drive north along highway 1 for about 10 minutes, turning right on highway 510 (signposted Hvanneyri), a potholed gravel road. (If you’re using Google Maps, note that it mislabels this road as highway 53.) Drive slowly. Soon you’ll cross a stream on wooden bridges and pass a farm called Ferjukot.

Then the old bridge called Hvítárbrú comes into view. This arched concrete bridge was built in 1928. The main route between Reykjavík and Borgarnes passed over it until the Borgarfjörður causeway was finished in 1983. The bridge has one narrow lane; before driving over, scan the far bank to make sure no one is coming toward you.

After crossing, follow signs for Reykholt, continuing along highway 510 and then turning north onto highway 50. Along the way, you’ll pass Fossatún (with the recommended Rock ’n’ Troll restaurant; described later) and the Brugghús Steðji (“Anvil”) microbrewery (no meals, Mon-Sat 13:00-17:00, closed Sun, tel. 896-5001). Just after the greenhouse village of Kleppjárnsreykir, near the junction of highways 50 and 518, turn left to stay on highway 50. After a minute or two, turn left at the sign for Deildartunguhver.

Option 3, Easier Route, via Highway 1 and Highway 50 (30 minutes): If crossing antique one-lane bridges makes you faint of heart, you can just drive north from Borgarnes about 20 minutes along highway 1 to the junction with highway 50, at the Baulan ÓB gas station; turn right here and drive 15 minutes until you see the small turnoff to the right marked Deildartunguhver.

To head back south to Reykjavík, you have two choices. Off-season, or in doubtful weather, play it safe and loop back south along highway 50 to return the way you came: on highway 1, past Hafnarfjall and Akrafjall mountains, and through the tunnel (about 1.5 hours).

In decent weather (generally May-Sept), I’d take the scenic route via the Dragháls pass and Hvalfjörður. From Reykholt, this adds about 30 minutes to your trip (2 hours to Reykjavík). It comes with some unpaved stretches (including a gravel pass that rises to several hundred feet above sea level). But the payoff is that Hvalfjörður feels more off-the-beaten-track than other day-trip destinations from Reykjavík, and comes with many fine views.

• From Reykholt, drive south on highway 50, then turn off onto gravel highway 520.

This road parallels Skorradalsvatn, a good fishing lake where you’ll see many summer cottages. Then it climbs over the low Dragháls pass to the east of the Hafnarfjall mountain system. Drive slowly and carefully, watching for potholes. Skirting a couple of small lakes, the road ultimately descends to Hvalfjörður (“Whale Fjord”), which you earlier traversed by undersea tunnel.

• Where the road tees, you’ll hit paved highway 47. Turn left, passing a tiny gas station (called Ferstikla) with a café that may be open in summer.

Take Highway 47 all the way around the fjord (a pretty drive that also saves you the tunnel toll). After about five minutes, you’ll pass the old Allied naval installation at Miðsandur (the only signpost you’ll see reads Hjálmsstaðir). The Nissen huts and camp here are Iceland’s best-preserved WWII-era buildings. The fjord here is quite deep. As the oil tanks on the far hillside suggest, this was a refueling station for ships, especially those traveling from North America to Murmansk in northern Russia. They could dock at two piers on either side of the camp.

After the war, the naval station was converted into a whale-processing facility. Today, slaughtered whales are still brought ashore at the eastern pier and processed in the buildings against the hillside. Iceland’s whaling company also owns the camp area. Everything is fenced off and signs make it clear that they don’t want you poking around (the station has been a target of animal-rights activists).

Highway 47 reaches the east end of the fjord (a small road here leads to the beginning of a challenging, two-hour hike to a high, pretty waterfall called Glymur). Next, the road doubles back along the south shore of the fjord. It crosses two rivers with fine waterfalls: Fossá (with a tiny, old, stone sheep pen next to the falls) and—farther along (next to the turnoff for road 48 to Þingvellir)—the low and beautiful Laxá. Unless it’s fogged in, you’ll be able to spot the metal smelters at Grundartangi on the far side of the fjord.

Ponder that until 1998, when the tunnel under Hvalfjörður was finished, this was the main road from Reykjavík to the north.

• After about 35 minutes, you’ll wind back to highway 1 near the south tunnel entrance, and turn toward Reykjavík, another 30 minutes away.

A pleasant town of approximately 2,000 people about an hour from Reykjavík, Borgarnes (BOHR-gahr-NESS) is the main hub of West Iceland. The town is set on a rocky peninsula jutting out into the estuary formed by the region’s several rivers, which merge near here (calling it a “fjord” is generous). A bridge and causeway, built in the early 1980s, cross the mouth of the estuary. Across the water from town, Hafnarfjall mountain—with its steep scree slopes—is an impressive sight.

Borgarnes was an important spot in the earliest days of Icelandic settlement. According to the sagas, this area was home to the early settler Skalla-Grímur Kveldúlfsson (“Grímur the Bald”; for background on the sagas, see here). After a bloody feud with Norwegian King Harald Fairhair, Skalla-Grímur fled Norway and sailed to Iceland. His father died on the journey, and—following Viking Age custom—Skalla-Grímur dropped his casket in the sea, then built his settlement where it washed ashore...at a place now called Borg, on the outskirts of Borgarnes. Skalla-Grímur lived out his days here, where he raised his son Egill Skallagrímsson (pronounced AY-ihtl). An even more dynamic figure than his father, Egill was ugly and passionate—equal parts battler and bard—and the protagonist of some of Iceland’s most colorful Settlement Age stories (now recounted in the town’s Settlement Centre). For those intrigued by the sagas, Borgarnes is a fun place to visit.

Arrival in Borgarnes: As you cross the causeway, you’ll pass the recommended Geirabakarí bakery (on the left). Just beyond, at the town’s main road junction, the N1 gas station also houses a free WC, the town’s bus station, and an expensive café and convenience store (long hours daily). Next door to the N1 complex is a Nettó supermarket, with the town TI inside (open daily in summer, off-season closed Sat-Sun; tel. 437-2214).

Turn left off the main road to reach the old part of town. The small park on your right has a few parking spaces where you can leave your car. Better yet, drive another couple of minutes down the main road to the Settlement Centre, which has a parking lot.

Get your bearings with this town orientation, either on foot or as you drive through. Start from the small park called Skallagrímsgarður (“Park of Grímur the Bald”)—with a few picnic tables—just off the main road from the top of the old town. The park is on the site of a burial mound thought to be Skalla-Grímur’s tomb. Down the side street next to the park (to the right from the main road) is Borgarnes’ good, large, outdoor swimming pool, which has fine sea views.

Continue a little farther down the main road. If you were to veer a couple of blocks to the left (down Bjarnarbraut), you’d find Borgarnes’ local museum, which tells the 20th-century history of Iceland from a child’s perspective (1,200 ISK, daily 13:00-17:00, likely closed off-season—but ask at the library upstairs if they’ll open it for you, Bjarnarbraut 4—look for a big red building marked museum, tel. 433-7200, www.safnahus.is).

At the end of town—just before the bridge—is the Settlement Centre (described on the next page).

Capping the hill above the Settlement Centre, look for a monument called Brákin, which resembles a giant wheel with wings. It’s an easy hike up to the monument, which offers nice views over the town, estuary, and Hafnarfjall mountain. The monument honors Egill’s nanny and de facto mother, a Celtic woman named Þorgerður Brák. According to the sagas, when an adolescent Egill angered his father during a game, Skalla-Grímur was about to beat the boy...likely to death. Brák stood up to Skalla-Grímur, who—now completely forgetting his son and furious with his servant—chased her to the top of this hill, where she leapt into the bay. Skalla-Grímur threw a giant stone at Brák, killing her in the water. Today the strait between Borgarnes and the mountain is still known as Brákarsund.

From the Settlement Centre, you can cross a bridge to the little island called Brákarey, home to Borgarnes’s tiny, not-very-good harbor. Borgarnes is one of a very few coastal towns in Iceland that did not form as a fishing center, and remains home to a mix of services and light industry.

Between the Settlement Centre and the Brákarey bridge, a little parking lot offers access to a pleasant waterfront trail. The path arcs around Englishmen’s Cove (Englendingavík) on the sleepy back side of the peninsula, where Englishmen reportedly lived during the Settlement Age. After passing a nice beach (and a recommended restaurant), the trail eventually leads to the town’s playing fields and swimming pool. From here, you’ll enjoy glorious views of the island and the mountains beyond.

This modest yet thoughtfully presented sight is Borgarnes’ best-known attraction and one of the prime places in Iceland to learn about the Settlement Age; for history buffs, it’s worth ▲▲. The center has two exhibits: one (upstairs) explaining how Iceland was discovered and settled, and the other (downstairs) retelling the grisly Egill’s Saga, which took place in and around Borgarnes. Each takes 30 minutes to see with the good, included audioguide.

Cost and Hours: Both exhibits-2,500 ISK, one exhibit-1,900 ISK, daily 10:00-21:00, Brákarbraut 13, Borgarnes, tel. 437-1600, www.landnam.is.

Visiting the Museum: The upstairs exhibit ponders the questions of why and how Viking Age settlers first came to Iceland. The exhibit is interactive: You can press buttons to light up the locations where various settlers first arrived, and stand on a Viking ship’s prow as it rocks back and forth on the waves.

The downstairs exhibition on Egill’s Saga illustrates that story, step by step, with interesting wooden figures and carvings by a local artist. Egill (c. 904-995) was a poet-warrior, mixing brutishness and sensitivity, who got into all sorts of trouble in both Iceland and Norway. He feuded with the king of Norway, wrangled with a witch, and married his foster sister (and brother’s widow). After two of his sons died, Egill composed Sonatorrek, a moving lament that is among the most famous examples of Old Norse poetry. By the age of 80, Egill—now a sour old man—toyed with the idea of throwing his wealth of silver pieces into the assembled crowds at Þingvellir, simply to start a riot. Instead, like his father before him, he buried his treasure somewhere in the Borgarnes area...where today, some people still look for it. For more on Egill’s story—and the rest of the sagas—see here.

Borgarnes has a big, pricey hotel, but I prefer these more affordable B&Bs. Borgarnes Bed & Breakfast and Kría Guesthouse are conveniently located on a bluff overlooking Englishmen’s Cove, on the quiet back edge of town. Egils Guesthouse and the hostel are right in the center.

$$ Borgarnes Bed & Breakfast, conscientiously run by Bertha and Ohioan Jay, rents eight modern, comfortable, bovine-themed rooms (most share bathrooms), and has an inviting breakfast room/lounge (Skúlagata 21, tel. 848-1129, www.borgarnesbb.is, info@borgarnesbb.is).

$$ Egils Guesthouse, less personal, rents rooms around town. Their Guesthouse Kaupangur, with a wonderfully central location above a café just up the stairs from the Settlement Centre, has five rooms—some with private bath. Across the street, tucked in a residential area, are a variety of studio apartments (breakfast extra, Brákarbraut 11, tel. 860-6655, www.egilsguesthouse.is, info@egilsguesthouse.is).

$ Kría Guesthouse has two spacious rooms that share a bathroom behind a beauty parlor (Kveldúlfsgata 310, tel. 437-1159, www.kriaguesthouse.is, info@kriaguesthouse.is).

¢ The Borgarnes Hostel is in the old town center, not far from the Settlement Centre (Borgarbraut 9, mobile tel. 695-3366, www.hostel.is, borgarnes@hostel.is).

$$ The Settlement Centre has the most appealing restaurant in town (just upstairs from the exhibit). You can eat here even if you don’t visit the museum itself. At lunch, they offer a good-value vegetarian buffet (daily until 15:00). It’s a substantial spread—soup, salads, pasta and potato dishes, and fresh fruit—and worth planning ahead for. At dinner, the restaurant has affordable main courses and expensive three-course fixed-price meals (restaurant open daily 12:00-21:00, same phone and hours as museum).

$ Geirabakarí bakery, the first building on the Borgarnes side of the causeway, serves budget lunches—soup with bread, sandwiches, and the like—and has tables with great views of Hafnarfjall and the water (Mon-Fri 7:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 8:30-17:00, Digranesgata 6—look for the gray-and-orange building marked HAGKAUP, tel. 437-2020, www.geirabakari.is).

$$ Englendingavík (“Englishmen’s Cove”) is a classy-feeling place that overlooks a beachy cove, with a few outdoor tables. It’s pricey by local standards, but scenic (daily 12:00-21:00, Skúlagata 17, tel. 840-0314, www.englendingavik.is).

A half-hour north of Borgarnes, highway 1 curls around the pint-sized volcanic cone of Grábrók (GRAU-broke, literally “Graypants”). In good weather, hiking up to its rim is easy, fun, and worth ▲▲.

Watch for the parking lot on the left, just after you pass the crater. From here, a well-marked path leads up into the rim. You can climb to the top in about 15 minutes, and—if it’s not too windy—stroll a path that circles the crater rim, which takes less than 10 minutes.

Grábrók was formed in an eruption about 2,000 to 3,000 years ago—around the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans—but there was no one here to see it. The beautiful lava field that you drive through just before reaching Grábrók flowed out in the same eruption. A thick layer of moss has grown on top of the lava, and changes color with the seasons.

From the top, enjoy stunning panoramas of the crater and the surrounding area. The classically conical mountain to the north is called Baula (BOY-la, which means “to moo”). Closer in, to the northwest, is a sinister, heavy-browed ridge called Hraunsnefsöxl. To the west, away from the road, is a second, similar-sized crater called Grábrókarfell. To the south (toward Borgarnes) is the campus of Bifröst, a small college originally founded to train managers for Iceland’s network of cooperative stores (and here I was hoping to find the Bifröst of the sagas: the rainbow bridge leading to Asgard, home to Óðinn (Odin) and other gods).

Just past Bifröst is Hreðavatn, a pretty lake with a managed forest at the far end. In the valley around you are both working farms and summer houses, some of them quite lavish.

As you descend Grábrók, look down along the slope to your left. You’ll see an odd stone structure with many compartments, which looks at first glance like it might be a prehistoric ruin. It’s actually a set of crudely built pens for rounding up sheep each fall, and it’s still in occasional use (it’s called Brekkurétt; rétt is the word for a sheep pen). You can walk through it if you’d like. If you continue farther north on the Ring Road, you’ll pass more elaborate, modern pens.

Sleeping and Eating near Grábrók: About five minutes past Grábrók crater, $$ Hraunsnef (“Lava Nose”) country hotel is a classy compound with cottages, a restaurant, and 15 straightforward rooms in various buildings. As it’s located just before the pass to the north, this place works well for those headed around the Ring Road (breakfast extra). The hotel’s fancy $$$ restaurant offers pricey main dishes and more affordable burgers (daily 12:00-21:00, lunch served mid-May-Aug only, tel. 435-0111, www.hraunsnef.is, hraunsnef@hraunsnef.is).

Other eating options include picnicking at Grábrók, or the roadhouse café called $ Hreðavatnsskáli, run by an Icelandic-Swiss chef who makes his own pasta (nice, casual atmosphere, daily 8:00-22:00, just beneath Grábrók on the Reykjavík side, tel. 421-1939, www.grabrok.is).

These sights fill the broad, sparsely populated valley of the Hvítá (“White River”), which flows from the Eiríksjökull glacier and empties into the estuary near Borgarnes. I’ve listed these roughly in order from west to east. Fitting all of these into a single day is doable but challenging; you’re better off being selective.

Stop for a few minutes at Europe’s most powerful hot spring, which gushes out almost 50 gallons of boiling water per second. Located off Highway 50 near Reykholt, here you’ll see steaming fountains of hot water spurting up next to a colorful rock face. Signs warn you not to touch the water. The beige concrete building is a pumping station that sends the water through a big pipe to Borgarnes and Akranes for home heating and bathing. You might find tomatoes from nearby greenhouses for sale from an honor box.

Deildartunguhver is the site of a brand-new premium thermal pool and bathing facility called Krauma; it’s open year-round (tel. 555-6066, www.krauma.is).

Continuing to Reykholt: From Deildartunguhver, return to the main road, head a half-mile downhill on highway 50, and turn left on highway 518, following signs five minutes to Reykholt.

Reykholt, set bucolically in the center of the valley, is home to a religious and scholarly complex devoted to medieval studies. While it’s boring for some, those excited about medieval Iceland and the sagas rate it ▲ for the chance to see its historic church and tour its museum. Scholars come on retreats here to write and use the fine library.

For 35 years, Reykholt was the home of Snorri Sturluson (1179-1241)—one of the most prominent figures of Iceland’s post-Settlement Age. A poet, historian, and politician, Snorri wrote some of the famous sagas, including—possibly—the locally set Egill’s Saga. Snorri was also a chronicler for all of medieval Scandinavia: He wrote Gylfaginning, a tale about the pantheon of Norse gods, and Heimskringla, the earliest and definitive history of Norwegian kings. Snorri was successful in the political realm, as well, serving two terms as the Alþingi’s law speaker and hobnobbing with the king of Norway. In fact, his support of continued union with Norway made him plenty of enemies back home—enemies who killed him in a surprise attack, right here at Reykholt. To this day, Snorri is arguably more popular among Norwegians (whose history he chronicled) than among Icelanders; the statue of him in Reykholt was done by Norway’s top sculptor, Gustav Vigeland.

Reykholt has two handsome churches, one small and traditional from the 1880s, the other large and modern from the 1990s (free). Underneath the modern church is the “Snorri’s Saga” Museum. It’s one large room, and is a bit dry (basically just posters), but modern and with good English—worth considering on a rainy day (1,200 ISK, daily 10:00-18:00, Oct-March until 17:00 and closed Sat-Sun, pay WCs, tel. 433-8000, www.snorrastofa.is).

The little outdoor hot pool, Snorralaug (Snorri’s Pool), has been here for hundreds of years (it’s mentioned in the sagas). Look for it behind the old school building, and unlatch the wooden door in the hillside behind the pool to see the first few feet of a tunnel. This once led to the cellar of a now-vanished building that was part of the complex in Snorri’s time. (Such tunnels were typical at the time, and there’s a similar one at Skálholt, along the Golden Circle.) Bathing in the pool is not allowed.

Sleeping near Reykholt: $$ Hótel Á (“River”), a five-minute drive past the recommended Brúarás café at the valley’s crossroads, is an endearingly rural option run by a local farmer’s family. Perched on a ridge overlooking the broad valley are 25 rooms with private bath (pricey dinner available to guests, Kirkjuból, Reykholt, tel. 435-1430, www.hotela.is, hotela@hotela.is).

$$ Fossatún (“Waterfall Field”) is a fun little compound along highway 50 between Borgarnes and Reykholt, just where the road crosses a small river, with a nice view over “Troll Falls.” They have 12 modern rooms with private bath in the hotel; six older, more rustic rooms with shared bath and kitchen in the guesthouse; and eight “camping pods” peppered throughout the property that share bathrooms and a kitchen (15 minutes from Reykholt, on-site Rock ’n’ Troll restaurant—see later, tel. 433-5800, www.fossatun.is, info@fossatun.is).

Eating in and near Reykholt: Several tree-sheltered picnic benches beckon on a nice day. At the back of the Snorralaug complex is the sleek, modern Fosshotel Reykholt, with a pricey $$$ restaurant—but I’d rather carry on just a few minutes to the excellent $ Brúarás Café, the best place to eat around here. In an angular, modern structure at the bridge where highways 518, 519, and 523 meet (between Reykholt and the waterfalls), it offers a brief but thoughtful menu of mostly locally sourced dishes, including lamb soup, burgers, and big salads. The café also serve as the area’s unofficial TI (restaurant open daily 11:00-17:00, mid-June-Aug until 20:00, closed off-season, tel. 435-1270, www.facebook.com/bruaras).

Toward Borgarnes from Reykholt, the Fossatún, listed earlier, also runs the $$ Rock ’n’ Troll restaurant, where the owner sometimes performs with his rock band (daily 18:30-21:00, in summer also 12:00-14:00).

These two waterfalls are a 20-minute drive up the valley from Reykholt along highway 518. They’re free and easy to see—just a few minutes’ walk from your car (free parking, pay WCs).

The main river running through the valley here is called the Hvítá (“White River,” the same name—but not the same river—as the one that flows over Gullfoss waterfall on the Golden Circle). As you approach the falls, you’ll see that the upper part of the valley is covered by relatively new lava. New lava is porous, and streams often sink into lava fields, flowing underneath the surface for considerable distances. At Hraunfossar (“Lava Waterfalls”), you’ll look across the river and see rivulets of groundwater pouring out from under the striped layers of lava on the other side and falling into the stream, like so many bridal veils.

A hundred yards upstream is Barnafoss, a more typical waterfall on the main stream. The name means “Children’s Waterfall,” and you can see what looks like the remains of a natural bridge spanning the falls here. According to legend, two children who were supposed to stay home while their parents were at church went out to play instead and drowned when they fell off the bridge; the mother destroyed the bridge so no other children would meet such a tragic fate. A pedestrian bridge over the river lets you get a closer look at the falls.

Eating at the Falls: By the waterfall parking lot is a small, basic $ café, with soup, snacks, ice cream, and coffee.

About 10 minutes past Barnafoss and the Hraunfossar, this hamlet is a service center for the union-owned cottages in the area that many Icelanders frequent. The area is anchored by a fancy hotel, with a variety of eateries (from a swanky dining room to a basic café/shop), and is the departure point for the “Into the Glacier” tours to Langjökull (described later). The main reason to stop here is to enjoy Húsafell’s surprisingly extensive thermal swimming pool, with multiple outdoor pools and a waterslide. Aside from the premium Krauma bath at Deildartunguhver, this is your best option in this part of West Iceland—and the most affordable (1,300 ISK, www.husafell.is).

Víðgelmir (VEETHE-GHELL-meer)—marketed as simply “The Cave”—is a lava tube formed about a thousand years ago during an eruption in the Langjökull volcano system. The top of a river of lava crusted over, enclosing the molten part underground. When the lava stopped flowing, it left behind a hollow, tube-like, mile-long corridor, now below ground level. Today visitors can take a guided walk through the lava tube and ogle its unusual lava formations: tubular lava stalactites shaped like strands of spaghetti, and formations that look like melted chocolate. While Víðgelmir requires a substantial commitment of time and money—and I’ve toured far more impressive caves in Europe—the volcanic spin makes this worth considering for rock nerds. Dress warmly—wear a jacket, hat, and gloves at any time of year; underground, the temperature hovers right around freezing.

Cost and Hours: 6,500 ISK, daily tours run hourly 9:00-18:00, fewer tours mid-Sept-mid-May—generally 4-5/day, confirm times before you go, mobile 783-3600, www.thecave.is. They prefer that you book and pay in advance online, rather than just showing up. If you’re running late for your tour time, they can normally switch you to a later tour on the same day.

Getting There: From Reykholt, it’s a 30-minute drive down a mostly unpaved road. Cross the bridge at highway 519, then head east along highway 523. You’ll drive to the end of a rough gravel road in the middle of a lava field.

Visiting the Cave: When you arrive, check in at a little shed, where you’ll be issued a helmet and a headlamp. Then you’ll walk across a petrified lava flow 300 yards to a hole formed centuries ago when part of the tube’s roof collapsed. Here you’ll climb down a wooden staircase and follow boardwalks through about a half-mile of the mile-long cave. You’ll see multicolored layers of basalt lava, which built up over the course of the long eruption, and get a good, up-close look at some remarkable lava formations. Remember, this is a lava cave, rather than a limestone cave: The “stalactites” and “stalagmites” weren’t formed over eons by dripping water, but all at once, a thousand years ago, as the liquid lava cooled and hardened. Your guide will point out where they found evidence of humans living here (perhaps a Viking Age outlaw); let you (gently) handle a few samples of the delicate lava formations; and flip off the lights so you can experience total darkness.

This is a one-family project by Jóhanna Þorvaldsdóttir and her clan, who idealistically set out a few years ago to breed Iceland’s nearly extinct goat stock—descended from animals brought by the first settlers. Now the family invites travelers to visit their farm, meet (and, if you like, cuddle) some adorable baby goats, learn about their work, watch the goats butt heads playfully, and sample (and buy) the wide variety of products they make from their goats: feta cheese, ice cream, soap and lotions (from tallow), and goat-hide carpets and insoles. This is a fun, hands-on activity for kids. I consider the cost of admission worthwhile just to keep this Icelandic tradition alive.

Cost and Hours: 1,500 ISK, June-Aug daily 13:00-18:00, Sept-May by appointment only, mobile tel. 845-2331, www.geitur.is, haafell@gmail.com.

Getting There: The farm is on gravel highway 523, about midway between the junctions with highways 522 and 519, on the north side of the river Hvítá. It’s about 20-25 minutes’ drive from Reykholt, depending on which way you circle around.

At the far upper end of the valley, a four-wheel-drive track leads up to the Langjökull glacier—Iceland’s second-largest. If you’re in the area (particularly if you’re overnighting and have extra time), consider paying for a pricey tour that gets you close to all that ice. Note, though, that the tours are time-consuming, there’s a lot to do in the valley on your own, and you can get close to glaciers more easily and cheaply in other parts of Iceland (such as Sólheimajökull, on the South Coast).

One popular experience is “Into the Glacier,” a tour that takes you into a cave that has been bored in the snow and ice. You’ll meet your tour at Húsafell and board an eight-wheel-drive super truck for the 30-minute transfer to the cave, where a guide will lead you around the tunnels. Bundle up—the temperature hovers right around freezing (20,000 ISK, 2,000 ISK extra for four-wheel drive shuttle, generally 6-7/day June-mid-Oct 10:00-15:30, fewer departures off-season, 2-3 hours total, also possible to combine with snowmobile trip or as an all-day excursion from Reykjavík, tel. 578-2550, www.intotheglacier.is).