SUPERMARKETS AND OTHER CHEAP EATS

USING A MOBILE PHONE IN ICELAND

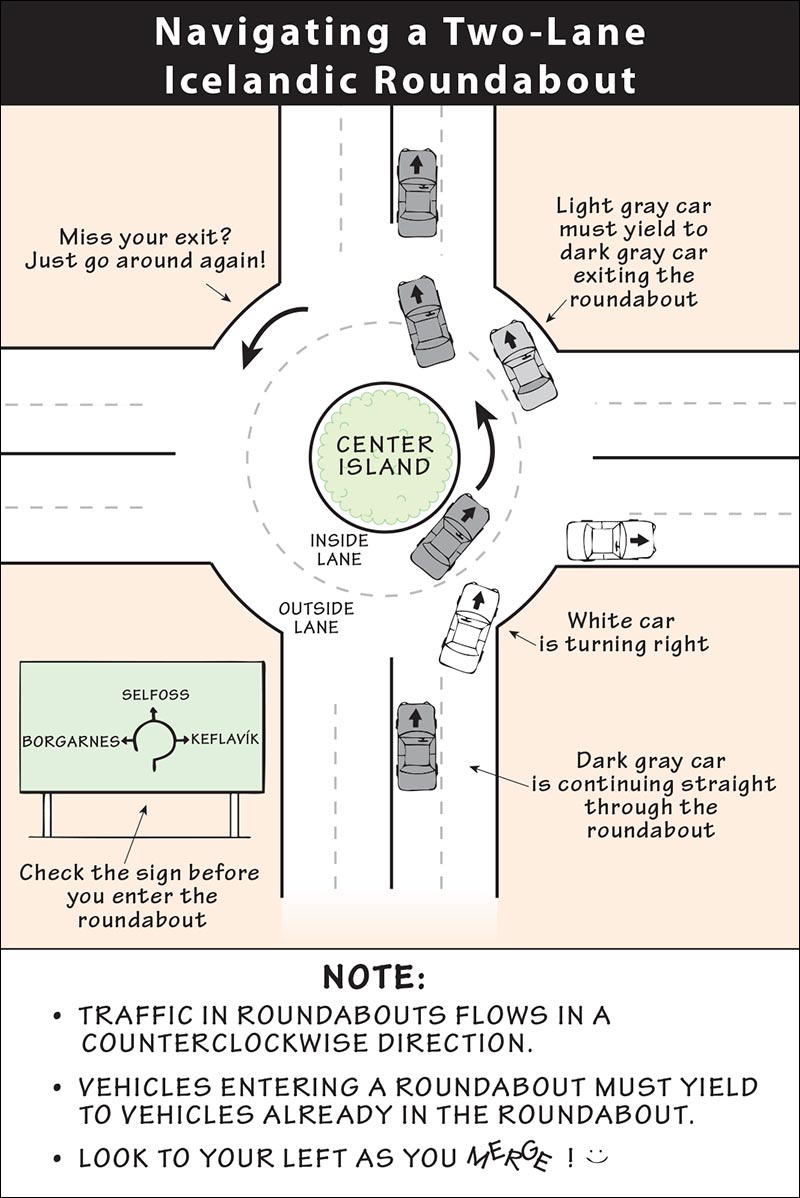

Map: Navigating a Two-Lane Icelandic Roundabout

This chapter covers the practical skills of Icelandic travel: how to get tourist information, pay for things, sightsee efficiently, find good-value accommodations, eat affordably but well, use technology wisely, and get between destinations smoothly. For more information on these topics, see www.ricksteves.com/travel-tips.

Iceland’s national tourist office offers practical information and trip-planning ideas on their website (www.visiticeland.com), which also links to good regional information.

In Iceland, a good first stop is generally the tourist information office—abbreviated TI in this book. While you can get plenty of information online, I still make a point to swing by the local TI to confirm sightseeing plans, pick up maps, and get information on transit (including excursion bus schedules), walking tours, special events, and nightlife.

Prepare a list of questions and a proposed plan to double-check. Some TIs have information on the entire country or at least the region, so try to pick up maps and printed information for destinations you’ll be visiting later in your trip.

Two thick, free booklets are especially useful for travelers in Iceland. Áning—Accommodation in Iceland lists swimming pools and campgrounds around the island (as well as hotels, guesthouses, and bus routes). Around Iceland is a directory of sights and services around the whole country, including useful maps. Both are advertising-supported, but comprehensive and fairly neutral. Download them at www.icelandreview.com/publications, or pick up paper copies once you arrive.

Emergency and Medical Help: In Iceland, dial 112 for all emergencies (police, fire, or ambulance).

For simple illnesses, go to a pharmacist for advice. For more complicated problems, ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services. Or dial 1770 to reach the efficient after-hours medical service called Læknavakt (www.laeknavaktin.is), available for phone consults at no charge weekdays from 17:00 to 8:00 and around-the-clock on weekends. Non-Europeans can pay a reasonable fee to visit any of Iceland’s state-run primary care centers (heilsugæslustöð) during business hours.

Theft or Loss: To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy or consulate (see here). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them (see “Damage Control for Lost Cards” on here).

File a police report either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for lost or stolen travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport or credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help.

Avoiding Theft: While Iceland is generally safe, if there are thieves or crooks about, they’ll target tourists. Keep a close eye on your suitcase and daypack, and don’t set valuables down absentmindedly.

Time Zones: Iceland doesn’t observe Daylight Savings Time (due to its far-north location, it’s already often either light or dark). In summer, Iceland is one hour behind Great Britain and four/seven hours ahead of the East/West coasts of the US. In winter, Iceland is on par with Great Britain and five/eight hours ahead of the East/West coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Europe “springs forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after most of North America) and “falls back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). During those weeks, Iceland is even with Great Britain and four/seven hours ahead of the East/West coasts of the US. For a handy online time converter, see www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

As Iceland’s clocks are set closer to Europe than the island’s geography justifies, the sun doesn’t reach its zenith in the sky until after 13:00, and rises and sets later in the day than you might expect. This is especially noticeable in winter.

Business Hours: Shops in Iceland are usually open from 10:00 or 11:00 until at least 18:00, with no lunch break. Supermarkets, other large retailers, and tourist-oriented shops are mostly open long hours daily, with slightly reduced weekend hours. Small shops often close early on Saturday. Banks are generally open Monday through Friday from 9:00 to 16:00.

Sundays have the same pros and cons as they do for travelers in the US: Sightseeing attractions are generally open, banks and smaller shops are closed, and public transportation options are fewer (for example, city buses may run only every 30-60 minutes). Friday and Saturday evenings are lively; Sunday evenings are quiet.

Watt’s Up? Like continental Europe, Iceland’s electrical system is 220 volts, instead of North America’s 110 volts. Most newer electronics (such as laptops, battery chargers, and hair dryers) convert automatically, so you won’t need a converter, but you will need an adapter plug with two round prongs, sold inexpensively at travel stores in the US.

Discounts: Discounts for sights are generally not listed in this book. However, seniors (age 60 and over), youths under 18, and students and teachers with proper identification cards (www.isic.org) can get discounts at many sights. Always ask.

Online Translation Tips: Google’s Chrome browser instantly translates websites. You can also paste text or the URL of a foreign website into the translation window at Translate.google.com. The Google Translate app converts spoken English into most European languages (and vice versa) and can also translate text it “reads” with your smartphone’s camera.

Here’s my basic strategy for using money in Iceland:

• Upon arrival, head for a cash machine (ATM) at the airport and withdraw a small amount of local currency, using a debit card with low international transaction fees.

• Keep your cash safe in a money belt.

• Pay for most purchases with a credit card with low (or no) international fees.

Icelanders rarely use cash; they pay with plastic even for small purchases such as parking meters and hot dogs. It’s possible to get through an entire Icelandic trip without ever using local cash.

In Iceland, I use my credit card nearly exclusively, for everything from hotel reservations and car rentals to everyday expenses such as meals and sightseeing. While you could use your debit card for some of these expenses, keep in mind that you have greater fraud protection with your credit card. The card you use may depend on which one charges the lowest international transaction fees.

Exceptions to Iceland’s all-plastic system are in-city buses, some coin-operated parking meters, and unstaffed pay WCs at countryside sights—where you’re asked, usually on the honor system, to put 100-200 ISK in a box (or the equivalent in US dollars). You could withdraw a couple thousand crowns and change them into 100 ISK coins for these WCs. Or just bring a handful of dollar bills to save a trip to the bank.

Don’t withdraw or exchange more Icelandic currency than you need. Most merchants prefer plastic, and you’ll scramble to spend unused crowns at the end of your trip. Whatever you do, don’t bring krónur home with you: It’s bothersome to exchange crowns back to dollars even in Iceland, and impossible (or possible only at punishing rates) outside the country.

I pack the following and keep it all safe in my money belt.

Credit Card: Use this to pay for most items (at hotels, larger shops and restaurants, travel agencies, car-rental agencies, and so on).

Debit Card: Use this at ATMs to withdraw local cash as needed (you’ll use your credit card more than cash).

Backup Card: Some travelers carry a third card (debit or credit; ideally from a different bank), in case one gets lost, demagnetized, eaten by a temperamental machine, or simply doesn’t work.

US Dollars: I carry $100-200 US as a backup. While you won’t use it for day-to-day purchases, American cash in your money belt comes in handy for emergencies, such as if your ATM card stops working.

What NOT to Bring: Resist the urge to buy krónur before your trip (you’ll pay the price in bad stateside exchange rates). Wait until you arrive to withdraw money. I’ve yet to see an airport that didn’t have plenty of ATMs.

Use this pre-trip checklist.

Know your cards. For credit cards, Visa and MasterCard are universal, American Express and Diners Club are less common, and Discover is unknown. Debit cards from any major US bank will work in any standard Icelandic bank’s ATM (ideally, use a debit card with a Visa or MasterCard logo).

Newer credit and debit cards have chips that authenticate and secure transactions. In Iceland, as in much of Europe, the cardholder inserts the chip card into the payment machine slot, then enters a PIN. (In the US, you provide a signature to verify your identity.)

Any American card, whether with a chip or an old-fashioned magnetic stripe, will work at Iceland’s hotels, restaurants, and shops. I’ve been inconvenienced a few times by self-service payment machines that wouldn’t accept my card, but it’s never caused me serious trouble.

If you’re concerned, ask if your bank offers a true chip-and-PIN card. Cards with low fees and chip-and-PIN technology include those from Andrews Federal Credit Union (www.andrewsfcu.org) and the State Department Federal Credit Union (www.sdfcu.org).

Report your travel dates. Let your bank know that you’ll be using your debit and credit cards overseas, and when and where you’re headed.

Know your PIN. Make sure you know the numeric, four-digit PIN for each of your cards, both credit and debit. Request it if you don’t have one and allow time to receive the information by mail.

Adjust your ATM withdrawal limit. Find out how much you can take out daily and ask for a higher daily withdrawal limit if you want to get more cash at once. Note that international ATMs will withdraw funds only from checking accounts; you’re unlikely to have access to your savings account.

Ask about fees. For any purchase or withdrawal made with a card, you may be charged a currency conversion fee (1-3 percent), a Visa or MasterCard international transaction fee (1 percent), and—for debit cards—a $2-5 transaction fee each time you use a foreign ATM (some US banks partner with European banks, allowing you to use those ATMs with no fees).

If you’re getting a bad deal, consider getting a new credit or debit card. Reputable no-fee cards include those from Capital One, as well as Charles Schwab debit cards. Most credit unions and some airline loyalty cards have low-to-no international transaction fees.

European cards use chip-and-PIN technology, while most cards issued in the US use a chip-and-signature system. But most Icelandic card readers can automatically generate a receipt for you to sign, just as you would at home. Some card readers will prompt you to enter your PIN (so it’s important to know the code for each of your cards). If a cashier is present, you generally should have no problem. At self-service payment machines (transit-ticket kiosks, parking garages, etc.), results are mixed, as US chip-and-signature cards aren’t configured for unattended transactions. If your card won’t work, look for a cashier who can process your card manually.

Drivers Beware: Be aware of potential problems using a credit card to fill up at Icelandic gas stations. Know your PIN, fuel up often, and be prepared to move on to the next gas station if necessary. For more tips on paying for fuel, see the “Driving” section, later in this chapter.

Some merchants and hoteliers cheerfully charge you for converting your purchase price into dollars. If it’s offered, refuse this “service” (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC). If, when you insert your chip card into a reader, you get a message asking whether you want to pay in dollars or Icelandic krónur, always choose krónur—you’ll pay extra for the expensive convenience of seeing your charge in dollars.

Icelandic cash machines (labled Hraðbanki) have English-language instructions and work just like they do at home—except they spit out local currency instead of dollars, calculated at the day’s standard bank-to-bank rate. When possible, withdraw cash from a bank-run ATM located just outside that bank. If your debit card doesn’t work, try a lower amount—your request may have exceeded your withdrawal limit or the ATM’s limit. If you still have a problem, try a different ATM or come back later—your bank’s network may be temporarily down.

Avoid “independent” ATMs, such as Travelex, Euronet, Moneybox, Cardpoint, and Cashzone, which have high fees.

Pickpockets target tourists. To safeguard your valuables, wear a money belt—a pouch with a strap that you buckle around your waist like a belt and tuck under your clothes. For convenience, you can carry a wallet with one credit card and a little cash in your front pocket, but it’s wise to secure your backup cards, passport, and bills in your money belt.

Before inserting your card into a payment machine, inspect the front. If anything looks crooked, loose, or damaged, it could be a sign of a card-skimming device. When entering your PIN, carefully block other people’s view of the keypad.

To access your accounts online while traveling, be sure to use a secure connection (see the “Tips on Internet Security” sidebar, later in this chapter).

If you lose your credit or debit card, report the loss immediately to the respective global customer-assistance centers. Call these 24-hour US numbers: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111).

You’ll need to provide the primary cardholder’s identification-verification details (such as birth date, mother’s maiden name, or Social Security number). You can generally receive a temporary card within two or three business days (see www.ricksteves.com/help for more).

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50.

Iceland is emphatically a no-tipping country. That means that you should not tip at restaurants, in taxis, in hotels, or anywhere else. Since you’ll pay for almost everything with plastic—and most people carry little or no cash—it’s difficult to tip even if you wanted to. A nice side effect of the tipless culture in Iceland is that waiters in Icelandic restaurants are usually happy to split the bill and let individual members of a group pay for their own order.

Despite the no-tipping culture, guides on bus tours and other excursions in Iceland will sometimes suggest that you tip them. While you’re free to slip them a little extra money (in any currency) for a job especially well done, you are neither expected nor required to. Icelandic labor law requires that employees receive a full basic wage, independent of any expected gratuities.

Wrapped into the purchase price of your Icelandic souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT, called VSK or virðisaukaskattur in Icelandic) of about 24 percent. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase more than 6,000 ISK (about $55) worth of goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. You must ring up the minimum at a single retailer—you can’t add up your purchases from various shops to reach the required amount. (If the store ships the goods to your US home, VAT is not assessed on your purchase.)

Getting your refund is straightforward...and worthwhile if you spend a significant amount on souvenirs.

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document. You may need to show ID. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. At your last stop in Iceland (most likely at Keflavík Airport), arrive an additional half-hour before you need to check in for your flight to allow time to find the customs office and process the paperwork. Before you check your luggage, find the tax refund desk (across from the car rental counters and marked with a large sign). Have your passport and ticket available, as well as the credit card you want the refund to go to. Show them your purchases, receipts, and forms, which they will stamp.

You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your hand-knit Icelandic wool sweater, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. After getting your paperwork stamped, bring it to the bank in the airport’s main hall; they are responsible for refunding VAT.

You can take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 31 days. Many processed and packaged foods are allowed, including vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. Fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed, with exceptions for some canned items. As for alcohol, you can bring in one liter duty-free (it can be packed securely in your checked luggage, along with any other liquid-containing items).

To bring alcohol (or liquid-packed foods) in your carry-on bag on your flight home, buy it at a duty-free shop at the airport. You’ll increase your odds of getting it onto a connecting flight if it’s packaged in a “STEB”—a secure, tamper-evident bag. But stay away from liquids in opaque, ceramic, or metallic containers, which usually cannot be successfully screened (STEB or no STEB).

For details on allowable goods, customs rules, and duty rates, visit http://help.cbp.gov.

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Iceland’s finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

A good map is essential for efficient navigation while sightseeing. The maps in this book are concise and simple, designed to help you locate recommended sights. Maps with more detail are available at local TIs and sold at bookstores.

You can also use a mapping app on your mobile device. Be aware that pulling up maps or looking up turn-by-turn walking directions on the fly requires an Internet connection: To use this feature, it’s smart to get an international data plan or to only connect with Wi-Fi. With Google Maps or City Maps2Go, it’s possible to download a map while online, then go offline and navigate without incurring data-roaming charges, though you can’t search for an address or get real-time walking directions. A handful of other apps—including City Maps 2Go and OffMaps—also allow you to use maps offline.

For advice about maps for drivers, see here.

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your top sights. Sightseeing in Iceland is distinctive in that many of the things you’ll want to see are natural wonders (volcanoes, geothermal areas, glaciers). Many are within striking distance of Reykjavík, but require a car or an excursion. You won’t typically have to worry about opening hours or admission (see below), but you will need to plan how you’ll get there. For advice, see the Near Reykjavík chapter.

For a one-stop look at opening hours in Reykjavík, see the “At a Glance” sidebar in that chapter. Many sights keep stable hours, but things change. It’s smart to confirm the latest by checking with the TI or individual sights’ websites.

Don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know when a place will close unexpectedly due to bad weather, a holiday, or restoration. Some sights are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Labor Day (May 1). A list of holidays is on here; check online for possible closures during your trip. In summer, some sights may stay open late; in the off-season, hours may be shorter or sights may be closed completely.

If you plan to hire a local guide, reserve ahead. Popular guides can get booked up.

Study up. To get the most out of the sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit.

Much of the sightseeing you’ll do in Iceland is outdoors—and almost all of that is free (there may be a charge for parking and WCs). Icelanders have lately been debating if this can endure, given rising tourist numbers and the cost of upkeep. Tickets, passes, or local taxes may figure in the future for some popular natural sights.

At Outdoor Sights: Usually you’ll park in a big, free parking lot (a few charge a fee). Near the parking lot, you’ll often find WCs (some pay, some free); a small café or snack stand; and orientation panels with a helpful introduction to the sight. Bigger sights might have a staffed visitors center where you can get more information.

For some natural attractions, expect a walk (5-15 minutes each way) to reach the sight itself from the parking lot. Always stay on marked trails—both for your own safety and to avoid disrupting the beauty you came to see.

In general, be aware that Iceland’s raw nature is as potentially dangerous as it is gorgeous. Read the “The Many Ways Iceland Can Kill You” sidebar in the Icelandic Experiences chapter; carefully review sight-specific details in this book; and heed any warning signs posted at the sight itself.

At Museums and Other Indoor Sights: You may not be allowed to enter if you arrive too close to closing time. Guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last. If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask. Pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask museum staff if you can’t find a particular item.

Audioguides and Apps: Many sights use audioguides, which generally offer useful recorded descriptions in English. Often, you’ll download the audioguide for free to your own mobile phone, using on-site Wi-Fi; if you want to rent an audioguide device (where available), you’ll pay a token amount.

Extensive and opinionated listings of good-value rooms are a major feature of this book’s Sleeping sections. I like places that are clean, central, relatively quiet at night, reasonably priced, friendly, small enough to have a hands-on owner or manager and stable staff, and run with a respect for Icelandic traditions. I’m more impressed by a convenient location and a fun-loving philosophy than flat-screen TVs and a fancy gym. Most places I recommend fall short of perfection. But if I can find a place with most of these features, it’s a keeper. My recommendations run the gamut, from dorm beds to fancy rooms with all the comforts. You can also consider a short-term rental, or camping your way around Iceland in a campervan.

Book your accommodations as soon as your itinerary is set, especially for Reykjavík and on the Ring Road (where there aren’t enough rooms to meet demand in the areas around Mývatn and Höfn). For the peak summer months, rooms can be completely booked up many months ahead. See the appendix for a list of major holidays and festivals in Iceland: Some—like Þjóðhátið in the Westman Islands—merit reserving far in advance. For tips on making reservations, see the “Making Hotel Reservations” sidebar later in this chapter.

Icelandic homes and smaller hotels rely on geothermal energy for heat. There’s usually no central thermostat, just individual controls on each radiator. Typically, if it gets too warm, Icelanders will open a window before they turn down the radiator.

Be aware that if you visit Iceland in June or early July, it will never get fully dark. Accommodations come with blackout curtains that try to darken your sleeping quarters, but some travelers still find it hard to sleep. Light sleepers will want to bring a nighttime eye mask.

I’ve categorized my recommended accommodations based on price, indicated with a dollar-sign rating (see sidebar). The price ranges suggest an estimated cost for a one-night stay in a standard double room with a private toilet and shower in high season, include breakfast, and assume you’re booking directly with the accommodation (not through a booking site, which extracts a commission). Room prices can fluctuate significantly with demand and amenities (size, views, room class, and so on), but these relative price categories remain constant.

Room rates are especially volatile at large hotels that use “dynamic pricing” to set rates. Prices can skyrocket during periods of peak demand, and discounted deeply on weekends when demand plummets. Of the many hotels I recommend, it’s difficult to say which will be the best value on a given day—until you do your homework.

Once your dates are set, check the specific price for your preferred stay at several places. You can do this either by comparing prices on Hotels.com or Booking.com, or by checking hotel websites. To get the best deal, contact family-run hotels directly by phone or email. When you go direct, the owner avoids the 20 percent commission, giving them wiggle room to offer you a discount, a nicer room, or free breakfast if it’s not already included. If you prefer to book online or are considering a hotel chain, it’s to your advantage to use the hotel’s website.

Some places offer a discount to those who stay longer than three nights. To cut costs further, try asking for a cheaper room (for example, with a shared bathroom or no window) or offer to skip breakfast.

Double rooms listed in this book range from $100 (very simple, toilet and shower down the hall) to $400 suites (maximum plumbing and more), with most clustering around $200-250. Most hotels also offer single rooms, and some offer larger rooms for four or more people (I call these “family rooms” in the listings). If there’s space for an extra cot, they’ll cram it in for you. In general, a triple room is cheaper than the cost of a double and a single. Three or four people can economize by requesting one big room.

In Iceland, hotels are usually large (big enough for groups), impersonal, and corporate-owned. If you want a more mom-and-pop feeling, look for guesthouses and farmstays (described below). An ample breakfast buffet is generally included.

Arrival and Check-In: If you’re arriving in the morning, your room probably won’t be ready. Check your bag safely at the hotel and dive right into sightseeing.

In Your Room: More pillows and blankets are usually in the closet or available on request. Towels and linens aren’t always replaced every day. Hang your towel up to dry.

Most hotel rooms have a TV, telephone, and free Wi-Fi. Simpler places rarely have a room phone, but usually have free Wi-Fi.

To guard against theft in your room, keep valuables out of sight. Some rooms come with a safe, and other hotels have safes at the front desk. I’ve never bothered using one, and in a lifetime of travel I’ve never had anything stolen from my room.

Checking Out: While it’s customary to pay for your room upon departure, it can be a good idea to settle your bill the day before, when you’re not in a hurry and while the manager’s in. That way you’ll have time to discuss and address any points of contention.

Hotelier Help: Hoteliers can be a good source of advice. Most know their town well, and can assist you with everything from route tips to finding a good restaurant or the nearest launderette.

Hotel Hassles: Even at the best places, mechanical breakdowns occur: Sinks leak, toilets may gurgle or smell, or the Wi-Fi goes out. Report your concerns clearly and calmly at the front desk. For more complicated problems, don’t expect instant results.

In downtown Reykjavík, street noise on Friday and Saturday nights can be high. If you find that noise is a problem (if, for instance, your room is over a nightclub), ask for a quieter room in the back or on an upper floor.

Above all, keep a positive attitude. Remember, you’re on vacation. If your hotel is a disappointment, spend more time out enjoying the place you came to see.

In the countryside, $150-200 buys you a simple room with a shared bathroom in a small guesthouse or rural farm accommodation. For a private bathroom, you’ll step up to the $250-300 range—and that often means a bigger property that’s less personal and charming. Even if you’re disinclined to share a bathroom, consider compromising from time to time—not only to save money, but also to land at a better place.

While becoming less common, at guesthouses and farmstays you may see separate prices for “made-up beds” and “sleeping-bag space.” Sleeping-bag space means that the guesthouse provides a mattress with sheet and pillow (no pillowcase); you bring your own sleeping bag. A made-up bed includes a comforter and duvet cover.

Guesthouses: Especially in Reykjavík and other towns, you’ll find plenty of small guesthouses with 5 to 10 rooms and shared bathrooms (some offer private bathrooms). Guesthouses are usually cozier, cheaper, and have more character than hotels, but tend to come with simpler amenities and smaller breakfasts.

Farmstays: Many Icelandic farms rent space to travelers, ranging from a room or two in the main farmhouse to a string of prefab cabins set up elsewhere on the property. Aside from Reykjavík, Iceland had practically no towns until the late 1800s—staying in the countryside lets you experience Iceland as it was for centuries. Sheep are the most common livestock (they’re up in the mountains during the summer), and some farms keep cows or horses; hay is the main crop. While farm families offer a cordial welcome, Icelanders tend to be reserved and you should mostly expect to be left alone. The Icelandic farm tourism association, cleverly branded as Hey Iceland, has a helpful interactive map on their website that lets you pick a spot (www.heyiceland.is, tel. 570-2700). Member farms also tend to list at Airbnb, Booking.com, and similar sites (described next).

A short-term rental—whether an apartment, house, or room in a local’s home—is an increasingly popular alternative, especially in expensive Iceland. Particularly in peak season, you can often find an apartment that costs approximately half what you’d pay at a hotel—likely with more space, a kitchen, and other features. You trade away the convenience of a staffed reception desk, a readymade breakfast option, and other hotel amenities, but the savings are substantial. And, while it varies dramatically, some short-term hosts are more helpful than any hotel receptionist. If you’re willing to stay in a room in someone’s home (rather than have an entire property to yourself), you can save even more.

Apartments: Icelandic apartments, like hotel rooms, tend to be small by US standards. But they often come with laundry facilities; a balcony, patio, or a private garden; and a small, equipped kitchen, making it easier and cheaper to dine in. If you make good use of the kitchen, you’ll save on your meal budget.

Private and Shared Rooms: Renting a room in someone’s home is a good option for those traveling alone, as you’re more likely to find true single rooms—with just one single bed, and a price to match. Some places allow you to book for a single night; if staying for several nights, you can buy groceries just as you would in a rental house.

Other Options: Swapping homes with a local works for people with an appealing place to offer and who can live with the idea of having strangers in their home (don’t assume where you live is not interesting to Icelanders). A good place to start is HomeExchange. Icelanders, who are the world’s heaviest per-capita users of this site, like traveling to North America and typically vacation abroad around the same time of year that Americans do (June-Aug). To sleep for free, Couchsurfing.com is a vagabond’s alternative to Airbnb. It lists millions of outgoing members, who host fellow “surfers” in their homes.

Finding Short-Term Accommodations: Aggregator websites such as Airbnb, FlipKey, Booking.com, and the HomeAway family of sites (HomeAway, VRBO, and VacationRentals) let you browse properties and correspond directly with Icelandic property owners or managers. Of these, Airbnb is definitely the biggest name in the Iceland short-term rental market. However, Airbnb is controversial here, where critics say it has exacerbated the chronic housing shortage in Reykjavík, driven up real estate prices, and made it harder for young people to afford their first home (Iceland has traditionally been a country where even young adults own rather than rent). That shouldn’t stop you from taking advantage of it, though.

Confirming and Paying: Before you commit to a rental, be clear on the details, location, and amenities. I like to virtually “explore” the neighborhood using the Street View feature on Google Maps. Also consider proximity to public transportation and how well-connected the property is to the rest of the city. Ask about amenities (elevator, air-conditioning, laundry, Wi-Fi, parking, etc.). Reviews from previous guests can help identify trouble spots.

Many places require you to pay the entire balance before your trip. It’s easiest and safest to pay through the site where you found the listing. Be wary of owners who want to take your transaction offline to avoid fees; this gives you no recourse if things go awry. Never agree to wire money (a key indicator of a fraudulent transaction).

A hostel provides cheap beds where you sleep alongside strangers for about $40-50 per night. Travelers of any age are welcome if they don’t mind dorm-style accommodations and meeting other travelers. Most hostels offer kitchen facilities, guest computers, Wi-Fi, and a self-service laundry. Hostels almost always provide bedding, but the towel’s up to you (though you can usually rent one for a small fee). Family and private rooms are often available.

Independent hostels tend to be easygoing, colorful, and informal (no membership required; www.hostelworld.com). You may pay slightly less by booking directly with the hostel.

Official hostels are part of Hostelling International (HI) and share an online booking site (www.hihostels.com or www.hostel.is). HI hostels typically require that you be a member or pay extra per night. Iceland has over 30 official hostels, more or less evenly distributed around the island. They’re generally clean, well-run, and a great value for solo travelers on a budget. Many are open all year, though the more rural hostels typically close from November or December to February or March.

In Iceland, you can rent a converted van or pickup outfitted with beds, which lets you drive around the island without needing to find a place to stay. Some campers even have four-wheel drive and high clearances that let you drive over the mountain roads in the interior. While a campervan rental isn’t cheap, it can cost less than other forms of accommodation, and lets you be more flexible with your itinerary.

Campervan Rentals: A two-bed, two-wheel-drive campervan outfitted with basic cooking gear and bedding will run you about $150/day in summer ($110/day in shoulder season). Larger vans and those with four-wheel drive are more expensive. Major campervan outfitters (all located near Reykjavík) include Kúkú Campers (tel. 415-5858, www.kukucampers.is), GO Campers (tel. 517-7900, www.gocampers.is), Cozy Campers (tel. 519-5131, www.cozycampers.is), and Happy Campers (near the Keflavík airport, tel. 578-7860, www.happycampers.is). You’ll also find campervans advertised on Airbnb.

Arrange your rental period to cover only the dates when you’ll be driving around the island: Begin and end your trip in the Reykjavík area—using public transportation or a rental car and sleeping in a regular bed—then pick up the camper from the Reykjavík suburbs.

Where to Camp: Once you’re out in the countryside, it’s generally OK to park discreetly overnight in any semipublic lot, unless a sign specifically prohibits it. As for showering, that’s what Iceland’s municipal thermal pools are for: You’ll pay a few extra dollars per day to clean up—and luxuriate—in endless hot water (an unofficial list of pools is at www.sundlaugar.is). Or pay to use the facilities at a campground along your route (see next).

If you prefer a more formal place to overnight, you’ll find inexpensive campgrounds (tjaldsvæði) all around the island. Most don’t require reservations and are open from about mid-May to mid-September. For an unofficial list, get the free Áning—Accommodation in Iceland booklet (downloadable from www.icelandreview.com/publications), or visit the unofficial website Tjalda.is. A 28-day pass that covers most campgrounds is sold at CampingCard.is.

Car Camping: Camping while driving a regular rental car has many of the same advantages as a campervan, and is cheaper. If you bring your own camping gear, make sure it’s suited to Iceland’s high winds and chilly temperatures. Or rent gear in Iceland: Iceland Camping Equipment, in downtown Reykjavík, rents everything you might need at fair prices (Barónsstígur 5, mobile tel. 647-0569, www.iceland-camping-equipment.com).

Traditional Icelandic cuisine isn’t too far removed from its Viking Age roots—relying heavily on anything hardy enough to survive the harsh landscape (lamb, potatoes), caught in or near the sea (fish, seabirds), or sturdy enough to withstand winter storage (dried and salted fish). Today’s chefs have built on this heritage, introducing international flavors and new approaches to old-style dishes. In recent years, Reykjavík has emerged as a foodie destination—with both high-end, experimental “New Icelandic” cuisine and a renewed appreciation for the country’s traditional, nose-to-tail “hardship” cuisines. The capital offers a wide variety of dining options, but even in the countryside, you’re never far from a satisfying meal.

Food and drink prices in Iceland are strikingly high, but it is possible to eat well here without going broke. There’s no tipping, taxes are built into prices, and restaurants cheerfully dispense free tap water, making eating out more reasonable than it might seem.

Icelanders eat three meals a day at about the same times as Americans. Breakfast (morgunmatur) in homes tends to be oatmeal, cereal with milk, or bread and cheese, but hotels and guesthouses will lay out a good spread with eggs and cold cuts. Lunch (hádegismatur) is served between about 11:30 and 13:00, while dinner (kvöldmatur) usually starts at 18:00.

I’ve categorized my recommended eateries based on price, indicated with a dollar-sign rating (see sidebar). The price ranges suggest the average price of a typical main course—but not necessarily a complete meal. Obviously, expensive specialties, fine wine, appetizers, and dessert can significantly increase your final bill.

The dollar-sign categories also indicate a place’s overall personality: Budget eateries include street food, takeout places, basic cafeterias, bakeries, and soup-and-bread buffets. Moderate eateries are nice (but not fancy) sit-down restaurants, ideal for a straightforward, fill-the-tank meal. Many of my listings fall in this category.

Pricier eateries are a notch up, with more attention paid to the setting, presentation, and cuisine. These are ideal for a memorable meal that doesn’t break the bank. And splurge eateries are dress-up-for-a-special-occasion swanky—typically with an elegant setting, polished service, and pricey and intricate cuisine.

I haven’t categorized places where you might assemble a picnic, snack, or graze: supermarkets, delis, ice-cream stands, cafés or bars specializing in drinks, and so on.

Not very long ago, it was unusual for Icelanders to eat outside the home or a workplace cafeteria, except on special occasions. But with the country’s increasing wealth (and the influx of tourism) over the last decade or two, restaurants have become much more popular. All restaurants are smoke-free, and all restaurant staff speak English.

In Reykjavík, lunches are a particularly good value, as many places offer the same quality and similar selections for far less than at dinner. Make lunch your main meal, then have a lighter evening meal at a café. Many places offer a lunch special—typically a plate of fish, vegetables, and a starch (rice or potatoes) for 2,000-3,000 ISK.

Outside Reykjavík, the easiest lunch spots are roadside grills—often connected to a gas station and serving hamburgers, hot dogs, and fries, and possibly breaded fish. Any decent-sized town will also have a real (if small) café or restaurant with better food.

The best and healthiest lunch option at a small café or bakery is often an all-you-can-eat soup buffet, which includes unlimited bread and butter. For about 1,500-2,000 ISK, this can make for a satisfying meal. Look for thick, homemade soups (such as lamb soup, kjötsúpa).

Paying: Icelandic restaurants are often very flexible about splitting the bill between several guests, and waiters will ask each person to recall what they ate. There really is no tipping at Icelandic restaurants, and credit cards are accepted everywhere. Perhaps because of the lack of tipping, it’s common even at quite respectable restaurants in Iceland to order and pay at the counter and then sit down, or to stand up and pay at the counter after your meal.

In this island nation, you’ll see fish (fiskur) on every menu, prepared just about every way you can think of—and some ways that might not have occurred to you. Look for fish-and-chips, smoked salmon, fried balls o’ cod, shrimp-on-a-sandwich, sushi, and hearty fish stew.

Icelandic fish is almost always very good. Don’t get hung up on fresh versus frozen—here, both are fine (fish that’s frozen at sea, right after it’s netted, often tastes the freshest, although never-frozen fish has better texture). Deboned fish filets are the mainstay of the Icelandic diet. Haddock (ýsa) is by far the most common, followed by cod (þorskur) and plaice (rauðspretta, a small flatfish like flounder or sole). You’ll also see more expensive salmon (lax) and arctic char (bleikja), both of which are farm-raised in pens.

Plokkfiskur (“mashed fish”) was traditionally made with whatever fish scraps were at hand. Today this fish gratin or hash is made from haddock or cod cooked with milk, butter, and chopped potatoes; it’s a comfort food, often eaten with sweet rye bread. You’ll sometimes see cod cheeks (gellur), and Icelanders eat the roe (eggs) of both cod and lumpfish. Lately, Icelanders have started to make fish chips, which look a bit like potato chips but are much more expensive.

One favorite Icelandic splurge is humar, which is typically translated on menus as “lobster” but is actually a 10-inch-long crustacean that’s somewhere between a prawn and a crayfish (a more precise name is “langoustine,” “Norway lobster,” or—in Britain—“scampi”). Humar is expensive and considered a delicacy; it’s often made into soup, but you can pay royally to enjoy it baked or sautéed in butter and garlic. Tiny precooked and peeled Greenland shrimp (rækjur) are often added to sauces or eaten on open-face sandwiches.

Grásleppa: Lumpfish, small and, yes, lump-like. Its eggs are dyed red and black, and widely sold in Iceland as kavíar.

Karfi: Atlantic redfish, also known as ocean perch; can be served steamed or deep-fried

Keila: Cusk; mild and sweet-flavored, similar to cod

Langa or blálanga: Ling, a long, slim whitefish

Lúða: Halibut

Makríll: Mackerel, often smoked or canned

Saltfiskur: Cod preserved in salt, then rinsed before cooking

Síld: Herring, generally pickled and eaten with bread

Silungur: Trout, farm-raised and often smoked

Skötuselur: Monkfish or anglerfish; only the firm-textured tail is eaten

Steinbítur: Wolffish, also known as ocean catfish; mild and sweet-flavored

Ufsi: Pollock, a whitefish that’s often fried

Don’t miss the chance to try the excellent Icelandic lamb (lambakjöt). Icelandic sheep range free, grazing on wild grass, resulting in a lean and tender meat. You’ll find leg of lamb, rack of lamb, and other top-notch preparations on menus. Kjötsúpa (literally “meat soup”), an Icelandic staple made with chunks of lamb and root vegetables, is a more traditional way to eat lamb that warms you on cold days. Hangikjöt, smoked lamb, may be served warm or cold. Svið, an acquired taste, is a sheep’s head that’s been split down the middle; you eat the cheeks and, if you like, the eye and tongue.

Icelanders have traditionally eaten only modest amounts of beef (nautakjöt), and almost no chicken (kjúklingur) or pork (svínakjöt)—but today the latter two make up more than half of local meat consumption. Like some other European countries, Icelanders eat the meat of young horses (called hrossakjöt or folaldakjöt), but it’s rare on menus.

Thanks to the Danes, hot dogs (pylsur) became a common snack in Iceland in the 20th century. Unlike the average American frankfurter, some Icelandic hot dogs contain lamb in addition to beef and pork—but you probably won’t taste the difference. You’ll find hot dogs sold at gas station grills and at stands around town, often near swimming pools and in shopping malls. Wieners come in a bun with your choice of condiments (mustard, ketchup, mayonnaise-based remoulade, chopped raw onions, and crispy fried onions are popular). To keep things simple, ask for “one with everything” (eina með öllu). At about 300 ISK, this makes for a good fill-me-up on the go.

Restaurants here market nonendangered minke whale meat to tourists as a special experience. You’ll see it offered both raw (like sushi) or grilled as steaks or on skewers. Some say it resembles beef—or, because it’s a bit gamey, perhaps deer or elk. Ahi tuna is perhaps the best comparison, in terms of flavor and texture. Whale isn’t a traditional Icelandic dish, and while some travelers enjoy the chance to sample it, others raise ethical concerns (see sidebar on the next page).

A few restaurants offer relatively expensive seabird dishes. You’ll be eating a member of the auk family (svartfugl)—more likely a guillemot or murre than a puffin, as Iceland’s puffin populations are currently low. These birds were, and still are, netted on seaside cliffs at certain times of year.

Iceland’s reindeer population, introduced from Sweden in the 1700s, isn’t large enough to support a large commercial market. But you may occasionally see it on the menu of a restaurant with a private source.

In deep winter, when food supplies ran low on the farm, Icelanders traditionally reached down to the bottom of the barrel and ate the least appetizing parts of their livestock, which they had preserved in sour whey. In the 20th century, nostalgic urban Icelanders started the custom of serving these dubious delicacies at parties and buffets in January and February. They’re known as þorramatur, after the Old Norse winter month of þorri.

The most commonly served dishes are pressed ram’s testicles (hrútspungar), which actually aren’t bad; liver and blood sausage (lifrapylsa, blóðmör, and slátur), somewhat similar to Scottish haggis; sheep’s head (described earlier); and fermented Greenland shark, cut up into smelly little cubes (hákarl). While a few restaurants sell (overpriced) tiny portions of “rotted shark” (as it’s casually called), the most affordable way to sample this is to buy a tiny tub in the food section of Reykjavík’s Kolaportið flea market.

As well as regular milk (mjólk), try thicker, fermented súrmjólk or AB-mjólk on your cereal. Protectionist policies make imported cheeses very expensive, and (perhaps because of the lack of competition) Icelandic cheese (ostur) is generally bland and undistinguished. The most flavorful hard cheeses are Óðals Tindur and Óðalsostur. Like other Scandinavians, Icelanders enjoy brown “cheeses” that are made from boiled-down, slightly sweetened whey. The soft, spreadable version, called mysingur (similar to Swedish messmör) is much more popular in Iceland than the hard mysuostur (which resembles Norwegian brunost). Rice pudding (grjónagrautur) with cinnamon is a comfort food and common snack.

Icelanders eat yogurts and other curdled milk products in endless varieties (plain, sweetened, low-fat, high-fat, sold with folding plastic spoons and caps full of muesli, and so on). Of the sweetened, flavored yogurts, the richest is called þykkmjólk (a real treat); a close second are the flavors sold as Húsavíkur jógúrt.

At the other end of the spectrum—and an Icelandic staple—is skyr (pronounced “skeer”), a plain, no-fat product made from skim milk that’s similar to Greek yogurt sold in the US. Though you’ll hear skyr hailed as a magical low-fat discovery, Icelanders have long agreed that skyr tastes best mixed with cream and fruit. It’s also good baked into cheesecakes.

Mysa is whey—the acidic liquid leftover from the cheese- or skyr-making process. Sold in cartons in the supermarket, it’s become trendy as a probiotic beverage (think kombucha). The taste is a mix of sweet and sour.

Icelanders have traditionally collected an edible lichen that grows wild here, called fjallagras (“mountain grass”). Fjallagras is added to breads and soups, and brewed into tea. The only fruits that grow easily in Iceland are berries—especially blueberries (bláber), crowberries (krækiber), and currants (rifsber). Potatoes do well here, as do turnips (the main starchy root vegetable before potatoes arrived from the New World). Then there’s rhubarb, often used in baking and jam.

Today, Icelanders also grow a range of vegetables—tomatoes, cucumbers, mushrooms—in massive, geothermally heated greenhouses, but even with the cheap energy here these are usually more expensive than imported equivalents.

Most grain won’t grow here, so all grains (except barley) are imported. Since rye was once the cheapest grain to buy, and lacking much wood or fuel, Icelanders learned to bake rye bread in makeshift ovens dug in hot spots in the ground, near geothermal springs. Today this dense, chocolate-brown bread, called rúgbrauð, is made with a little barley malt or other sugar, and baked slowly at a low temperature, making it slightly sweet and cake-like. It’s often served with plokkfiskur (fish gratin) or just with butter for breakfast. Another traditional rye bread, flatbrauð is an unleavened, flat circle baked in a pan; it resembles a soft tortilla. It’s typically buttered and topped with sliced smoked lamb.

The island’s bakeries make several characteristic wheat-based pastries, many with Danish origins. Vínarbrauð (like a danish), sold at bakeries in long, wide strips, is usually filled with jam and topped with a stripe of sugary glaze. Kleinur are knots of deep-fried dough; sold fresh, singly, in bakeries or in bags in the supermarket, they go well with a cup of coffee.

A relic from earlier times is laufabrauð (“leafbread”), paper-thin circles of wheat-flour dough, which Icelanders, in the weeks before Christmas, inscribe with patterns and fry (traditionally in sheep tallow, these days more often in oil). You’ll see round containers of factory-made laufabrauð on sale in supermarkets in December.

Chocolate-covered licorice is the signature Icelandic candy. Supermarkets sell dozens of varieties on this theme, such as Draumur (“Dream”) candy bars and bags of olive-shaped Kúlu-súkk—the name is a play on the words for ball (kúla), chocolate (súkkulaði), and the Greenlandic town of Kulusuk. By European standards, Icelandic licorice is very tame, with little salt and a mild flavor. Some like fylltar reimar, hollow ropes of licorice stuffed with a sugary filling. Iceland’s thriving candy industry (the islanders are still making up for centuries of deprivation) also cranks out lots of licorice-free sweets and chocolates, such as the inexpensive Hraun (“Lava”) bars, whose rocky surface resembles a lava field.

Like other Scandinavians, Icelanders prefer soft-serve ice cream. When you order your cone, prepare to say whether, for a few extra krónur, you’d like it með dýfu (dipped into a chocolate sauce that hardens over the cold ice cream), með kurli (rolled in little chocolate beads), or both. At better ice-cream shops, a bragðarefur (literally “flavor fox”) is soft ice cream blended with your choice of chocolate chunks, crushed candy bars, nuts, or other goodies (basically like a gigantic McFlurry). Ask for two spoons.

Perhaps because so much of the country’s food is imported (and many native dishes are so unpalatable), Icelanders are very open to other cooking traditions. A wave of Thai, Vietnamese, and Filipino immigrants came to the country in the 1980s, and now you can buy coconut milk, tofu, and fish sauce at the discount supermarket Bónus. Icelanders love pizza (though Italians here are few), and the American military presence has left behind a taste for Cheerios and Doritos. And in the last couple of decades, Polish immigrants have opened a couple of good supermarkets and started to produce fine sausage.

Travelers can save money, especially at dinnertime, by assembling a picnic at one of Iceland’s supermarkets. The two discount supermarket chains, Bónus and Krónan, are the names to know. Hagkaup is more expensive, but carries a wider range, and some Reykjavík branches are open daily 24 hours. Samkaup is common in the countryside (but not particularly cheap). Steer clear of the extremely high-priced 10-11 convenience stores when possible.

Hagkaup and other larger supermarkets sometimes have a hot food counter with grilled chickens or roasted meats sold by weight. Supermarkets also sell prepared sandwiches, soft cheeses, shrimp and tuna “salads” that can be spread on bread, and plenty of cold cuts.

Other than Subway and Domino’s, major fast-food franchises have only a slight presence in Iceland. (That means no McDonald’s...and no Starbucks. You’ll survive.)

Restaurants dispense the country’s excellent tap water (vatn) for free, sometimes from a help-yourself table with pitchers and a stack of glasses. Buying bottled water is a waste of money here, unless you want it with bubbles—in that case, look for kolsýrt (carbonated) vatn or sódavatn. Blueberry is the country’s only native juice (safi or djús), an expensive delicacy produced in small quantities in the fall.

Icelanders are among the world’s biggest coffee (kaffi) drinkers. Many cafés and restaurants offer free refills. For other hot beverages, look for tea (te) or hot chocolate (heitt súkkulaði or kakó).

Icelanders love malt soda (malt), a sweetened and carbonated beverage made from yeast, malt, and hops just like beer, but with little or no fermentation. Egils Maltextrakt is the best-loved brand. Though thought of as nonalcoholic, Icelandic malt reportedly contains about 1 percent alcohol, which is not mentioned on the label. That means you’d need to drink practically a six-pack of malt to get the same effect as from one beer. At Christmas time, Icelanders like to mix malt fifty-fifty with orange soda; they call the result jólaöl (Yule ale).

All wine (léttvín) in Iceland is imported. Light beer (bjór; 2.25 percent alcohol) is sold in supermarkets, but for anything stronger you’ll need a state-run Vínbúðin store (or a bar or restaurant). Prices are high, especially for wine and spirits. If you plan to seriously imbibe during your visit, make a point of stopping at the airport duty-free store on your way into the country, before you retrieve your luggage. Prices are 20-50 percent lower than in Reykjavík, and the limit is generous. (You can plan your purchases, and check the current allowances, at www.dutyfree.is.)

In recent years, many small craft breweries have sprung up in Iceland, offering interesting alternatives to the major Scandinavian and local beer brands like Tuborg and Viking. There’s even a holiday dedicated to beer—Beer Day, on March 1, marks the 1989 end of the country’s 74-year prohibition of beer.

The local hard liquor industry has also diversified, and produces a range of vodka, gin, and even local single-malt whiskey. You’ll also see liqueurs made with local berries. Björk is a liqueur flavored with birch and even comes with a birch twig in the bottle. The most traditional strong spirit, called brennivín (and marketed as “Black Death”—you’ve been warned!) is an aquavit similar to vodka, made from fermented potatoes and flavored with caraway.

One of the most common questions I hear from travelers is, “How can I stay connected?” The short answer is: more easily and cheaply than you might think.

The simplest solution is to bring your own device—mobile phone, tablet, or laptop—and use it just as you would at home (following the tips below, such as connecting to free Wi-Fi whenever possible). Another option is to buy an Icelandic SIM card for your mobile phone—either your US phone or one you buy abroad. Or you use Icelandic landlines and computers to connect. Each of these options is described below; more details are at www.ricksteves.com/phoning. For a very practical one-hour talk covering tech issues for travelers, see www.ricksteves.com/travel-talks.

Here are some budget tips and options.

Sign up for an international plan. To stay connected at a lower cost, sign up for an international service plan through your carrier. Most providers offer a simple bundle that includes calling, messaging, and data. Your normal plan may already include international coverage (T-Mobile’s does).

Before your trip, call your provider or check online to confirm that your phone will work in Iceland, and research your provider’s international rates. Activate the plan a day or two before you leave, then remember to cancel it when your trip’s over.

Use free Wi-Fi whenever possible. Unless you have an unlimited-data plan, you’re best off saving most of your online tasks for Wi-Fi. You can access the Internet, send texts, and make voice calls over Wi-Fi.

Most accommodations offer free Wi-Fi, and many cafés have free hotspots for customers; look for signs offering it and ask for the Wi-Fi password when you buy something. You’ll also often find Wi-Fi at TIs, major museums, public-transit hubs, airports, and aboard some buses.

Minimize the use of your cellular network. Even with an international data plan, wait until you’re on Wi-Fi to Skype, download apps, stream videos, or do other megabyte-greedy tasks. Using a navigation app such as Google Maps over a cellular network can take lots of data, so do this sparingly or use it offline.

Limit automatic updates. By default, your device constantly checks for a data connection and updates apps. It’s smart to disable these features so your apps will only update when you’re on Wi-Fi, and to change your device’s email settings from “auto-retrieve” to “manual” (or from “push” to “fetch”).

When you need to get online but can’t find Wi-Fi, simply turn on your cellular network just long enough for the task at hand. When you’re done, avoid further charges by manually turning off data roaming or cellular data (either works) in your device’s Settings menu. Another way to make sure you’re not accidentally using data roaming is to put your device in “airplane” mode (which also disables phone calls and texts), and then turn your Wi-Fi back on as needed.

It’s also a good idea to keep track of your data usage. On your device’s menu, look for “cellular data usage” or “mobile data” and reset the counter at the start of your trip.

Use Wi-Fi calling and messaging apps. Skype, Viber, FaceTime, and Google+ Hangouts are great for making free or low-cost voice and video calls over Wi-Fi. With an app installed on your phone, tablet, or laptop, you can log on to a Wi-Fi network and contact friends or family members who use the same service. If you buy credit in advance, with some of these services you can call any mobile phone or landline worldwide for just pennies per minute.

Many of these apps also allow you to send messages over Wi-Fi to any other person using that app. Be aware that some apps, such as Apple’s iMessage, will use the cellular network if Wi-Fi isn’t available: To avoid this possibility, turn off the “Send as SMS” feature.

With an Icelandic SIM card, you get an Icelandic mobile phone number and access to cheaper rates than you’ll get through your US carrier. This option works well for those who want to make a lot of voice calls or need faster connection speeds than their US carrier provides. Fit the SIM card into a cheap phone you buy in Iceland, or swap out the SIM card in an “unlocked” US phone (check with your carrier about unlocking it).

A SIM card that also includes data (and roaming) will cost a little more than one that covers only voice calls. The most efficient way to buy an Icelandic SIM card is either on the plane (Icelandair flight attendants sell them) or at Keflavík Airport (before you claim your bags, detour into the duty-free store; after you exit, visit the 10-11 and Elko convenience stores in the arrivals hall). If you wait until you’re in Reykjavík, you can find phone-company stores in the Kringlan and Smáralind shopping malls. The two companies to consider are Síminn (www.siminn.is) and Vodafone (www.vodafone.is); they offer comparable starter packages for about 2,000-3,000 ISK, depending on how much data is included. Ask a store clerk or friendly local to help you insert your SIM card, set it up, and show you how to use it. You can top it up with cards bought at gas stations, convenience stores, supermarkets, and phone-company stores.

It’s less convenient but possible to travel in Iceland without a mobile device, using landlines and public computers. Most hotels charge a fee for placing calls—ask for rates before you dial. You can use a prepaid international phone card (one brand in Iceland is called AtlasFrelsi, sold at supermarkets, convenience stores, and gas stations). These cards offer a cheaper rate if you access the system by calling the landline, and a higher rate if you call the toll-free number.

Many hotels have a computer in their lobby for guests to use, and some may let you borrow a laptop. If typing on an Icelandic keyboard, use the “Alt Gr” key to the right of the space bar to insert the extra symbol that appears on some keys. For example, to insert an @ symbol, press the “Alt Gr” key and Q at the same time. If you can’t locate a special character, simply copy and paste it from a web page.

You can mail one package per day to yourself worth up to $200 duty-free from Europe to the US (mark it “personal purchases”). If you’re sending a gift to someone, mark it “unsolicited gift.” For details, visit www.cbp.gov, select “Travel,” and then “Know Before You Visit.” The Icelandic postal service works fine, but for quick transatlantic delivery (in either direction), consider services such as DHL (www.dhl.com).

Your options for linking destinations in Iceland are tourist-oriented excursion buses, unguided do-it-yourself excursion buses, public buses, rental cars, and short-hop flights. (Iceland has no rail system.)

If you’re staying in Reykjavík and plan only a few brief forays outside the city, you can get by without a car. But most visitors find that renting a car gives them maximum flexibility for getting out into the Icelandic countryside. You won’t find convenient public transportation options for reaching some sights (including the biggies—the Golden Circle and South Coast); instead you’ll likely need to rely on pricey excursions. For this reason, renting a car can be more cost-effective than it initially seems.

For general information on transportation throughout Europe, see www.ricksteves.com/transportation.

You can select from a full menu of guided bus tours to get into the countryside. You’re paying a premium for a guide and a carefully designed experience, but these excursions take the guesswork out of your trip. For more on this option, see the Near Reykjavík chapter.

In summer months, several private companies offer direct, regularly scheduled bus transport to many popular outdoor destinations, especially spots off the Ring Road and in the interior, such as Þórsmörk and Landmannalaugar. These buses are unguided, with routes intended to get hikers and campers to popular outdoor destinations, but anyone can use them to reach some of Iceland’s most spectacular sights.

For example, you can leave Reykjavík early in the morning, spend a couple of midday hours taking a short hike in Þórsmörk or Landmannalaugar, and return to the city for a late dinner; you could also overnight in a tent or cabin and get picked up the next day. These buses can come in handy for day-tripping from Akureyri to Dettifoss, or from Skaftafell to the Lakagígar craters.

Companies to consider include Reykjavík Excursions (under the name Iceland On Your Own, www.ioyo.is), Sterna Travel (www.icelandbybus.is or www.sternatravel.com), and Trex (www.trex.is). Confirm your departure location in Reykjavík; there may be several options. Reykjavík Excursions, Sterna, and Trex buses stop at the BSÍ bus terminal, which is within walking distance of downtown. Note that several of these companies also offer guided trips to some of the same destinations.

Highland Route to the North: An exciting bus journey is to travel from Reykjavík to the north (Skagafjörður, Akureyri, or Mývatn) through Iceland’s interior Highlands, over either of two passes—Kjölur or Sprengisandur. The trips run only when the passes are clear—usually from late June to early September. The route, which can’t be driven in a normal rental car, gives you a look at some of Iceland’s most desolate and remote scenery. (The high-clearance buses have large tires that can cope with the rocky roads...be prepared for a very bumpy ride.)

East Iceland: Reykjavík Excursions and Sterna also run one daily bus in each direction around the east end of the island, between Akureyri and Höfn.

Circle Passes: The bus companies offer passes (about 40,000 ISK) that allow you to circle the island, stopping wherever you like (early June-early Sept only). If you’re planning to loop through several parts of Iceland by bus, one of the “passport”-style fares can be handy—they’re essentially hop-on, hop-off tickets covering a specific route and cheaper than paying for individual journeys.

Iceland has a good network of scheduled public buses (painted yellow and blue and called strætó), run as a single system by city and local governments (www.straeto.is). The Strætó system doesn’t cover the country’s sparsely populated eastern edge (from Egilsstaðir to Höfn), but a privately run bus service fills in the gaps.

Although the Strætó network is more geared to locals than visitors, it can be useful to those traveling from one town to another, such as from Reykjavík to Selfoss or Akureyri. Reykjavík city buses are part of the Strætó network and use the same tickets and fare structure.

For long-distance trips, you can pay by credit card or through a Strætó app (see here). Strætó’s buses also accept cash (although no one pays this way) and little brown paper tickets (sold only in 20-ticket strips). From Reykjavík, Strætó’s long-distance buses leave from a terminal in the suburbs called Mjódd, which is linked to downtown by frequent city buses (ask driver for a free transfer ticket).

Car rental makes a lot of sense in Iceland, unless you’re traveling solo. Two people splitting the cost of a rental car and gas will save a lot over the cost of bus excursions, while enjoying the flexibility of stopping whenever and wherever they want. The Ring Road is practically made for road trips with friends. (For a Ring Road trip, also consider a campervan rental—see here.)

Rental companies require you to be at least 21 years old and to have held your license for one year. Drivers under the age of 25 may incur a young-driver surcharge, and some rental companies do not rent to anyone 75 or older.

Research car rentals before you go. It’s cheaper to arrange most car rentals from the US. Consider several companies to compare rates. Most of the major US rental agencies (including Avis, Budget, Enterprise, Hertz, and Thrifty) have offices in Iceland. Also consider the two major Europe-based agencies, Europcar and Sixt. Iceland’s smaller, homegrown rental agencies may offer cheaper used vehicles (beware that some of these cars are real clunkers—read carefully before booking). Or consider using a consolidator, such as Auto Europe/Kemwel (www.autoeurope.com—or the often cheaper www.autoeurope.eu), which compares rates at several companies to get you the best deal—but because you’re working with a middleman, it’s especially important to ask in advance about add-on fees and restrictions.

Always read the fine print or query the agent carefully for add-on charges—such as one-way drop-off fees, airport surcharges, or mandatory insurance policies—that aren’t included in the “total price.”

For the best deal, rent by the week with unlimited mileage. To save money on fuel, request a diesel car. I normally rent the smallest, least-expensive model with a stick shift (generally cheaper than an automatic). Almost all rentals are manual by default, so if you need an automatic, request one in advance.

Many tourists think of a trip to Iceland as more of an “expedition” than it really is, and shell out for a high-clearance SUV when they would do just fine with a teeny two-wheel-drive car. You won’t need four-wheel drive for the itineraries in this book in summer, or for a quick winter stopover if you stick to Reykjavík. A more rugged vehicle makes sense only if you’re planning to traverse Iceland’s interior Highlands (not covered in this book), drive outside the capital area in winter, ford unbridged rivers (such as on the road to Þórsmörk), or spend lots of time on mucky, rutted dirt roads in the countryside.

Air-conditioning isn’t standard in all of Iceland’s rental cars, but don’t pay extra to get it. Although cars can heat up when parked on a sunny summer day, the outside air temperature is never that warm, so rolling down the window is enough to cool things down.

In Iceland, figure on paying roughly $350 for a one-week rental in summer, and $50-100 less in spring or fall. Allow extra for supplemental insurance, fuel, tolls, and parking.

Most visitors to Iceland pick up their rental car either at Keflavík Airport or at the rental company’s Reykjavík office. It’s generally easiest to pick up and drop off at the airport, which has the widest selection of on-site rental operators. It’s also possible to pick up in Reykjavík and drop off at the airport (or vice-versa). This is considered a one-way rental, with a small extra charge (but often less than the airport bus fare).

Car rental in Akureyri and some smaller towns is also possible.

Always check the hours of the location you choose: Off-airport, many rental offices close from midday Saturday until Monday morning and, in smaller towns, at lunchtime.

When selecting a location, don’t trust the agency’s description of “downtown” or “city center.” In Reykjavík, these locations are all either at the domestic airport or in industrial areas on the outskirts of the city—a long, costly taxi ride from the center. Before choosing, plug the addresses into a mapping website.

When you pick up the rental car, check it thoroughly and make sure any damage is noted on your rental agreement. Rental agencies in Europe tend to charge for even minor damage, so be sure to mark everything. Before driving off, find out how your car’s gearshift, lights, turn signals, wipers, radio, and fuel cap function, and know what kind of fuel the car takes (diesel vs. unleaded). When you return the car, make sure the agent verifies its condition with you. Some drivers take pictures of the returned vehicle as proof of its condition.

Off-Limit Roads: Be clear on where you can drive your rental car. Normal two-wheel-drive vehicles are fine for well-maintained unpaved roads. But rental cars can’t be driven on roads in the interior, which cross unbridged rivers and can be very rough. (If you want to drive on these roads, rent a four-wheel-drive vehicle.) Consider any road designated with an “F” on maps or road signs to be off-limits. Highway 35 (over the Kjölur pass) and highway 550 (called Kaldidalur) are also off-limits even though they don’t have an F—this should be stated on your rental agreement.

When you rent a car, you are liable for a very high deductible, sometimes equal to the entire value of the car. Limit your financial risk with one of these options: Buy Collision Damage Waiver (CDW) coverage with a low or zero deductible from the car-rental company, get coverage through your credit card (free, if your card automatically includes zero-deductible coverage), or get collision insurance as part of a larger travel-insurance policy.

Basic CDW includes a very high deductible (typically $1,000-1,500), costs $15-30 a day (figure roughly 30-40 percent extra) and reduces your liability, but does not eliminate it. When you reserve or pick up the car, you’ll be offered the chance to “buy down” the basic deductible to zero (for an additional $10-30/day; this is sometimes called “super CDW” or “zero-deductible coverage”).

If you opt for credit-card coverage, you’ll technically have to decline all coverage offered by the car-rental company, which means they can place a hold on your card (which can be up to the full value of the car). In case of damage, it can be time-consuming to resolve the charges with your credit-card company. Before you decide on this option, quiz your credit-card company about how it works.

If you’re already purchasing a travel-insurance policy for your trip, adding collision coverage can be an economical option. For example, Travel Guard (www.travelguard.com) sells affordable renter’s collision insurance as an add-on to its other policies; it’s valid everywhere in Europe except the Republic of Ireland, and some Italian car-rental companies refuse to honor it, as it doesn’t cover you in case of theft.

Car-rental agencies may encourage you to spend upwards of $25/day for supplemental insurance to cover damage from sandstorms (blowing sand can ruin a car’s finish and gravel can break windows). Depending on where you’re driving, this isn’t always worthwhile (sandstorms are most likely to occur between Vík and Skaftafell on the Ring Road). You may also be offered insurance against damage from volcanic ash. Unless there’s an active eruption, the risk from ash is very low.

For more on car-rental insurance, see www.ricksteves.com/cdw.

Navigating in the Icelandic countryside is fairly easy. Signage is good (though the lettering on signs can be quite small), there’s only one Ring Road (though many side roads), and free paper maps and/or downloaded maps on the device of your choice are usually enough to get you around. If you’ll be navigating using your phone or a GPS unit from home, remember to bring a car charger and device mount.

Your Mobile Device: The mapping app on your mobile phone works fine for navigation in Iceland, but for real-time turn-by-turn directions and traffic updates, you’ll generally need Internet access. And driving all day while online can be very expensive if you are on a limited data plan. Helpful exceptions are Google Maps, Here WeGo, and Navmii, which provide turn-by-turn voice directions and recalibrate even when they’re offline.

Download your map before you head out—it’s smart to select a large region. Then turn off your cellular connection so you’re not charged for data roaming. Call up the map, enter your destination, and you’re on your way. View maps in standard view (not satellite view) to limit data demands.

GPS Devices: If you prefer the convenience of a dedicated GPS unit, consider renting one with your car ($10-30/day). These units offer real-time turn-by-turn directions and traffic without the data requirements of an app. Also make sure your device’s language is set to English before you drive off.

A less-expensive option is to bring a GPS device from home. Be aware that you’ll need to buy and download maps of Iceland before your trip.

Maps and Atlases: Even when navigating primarily with a mobile app or GPS, I always make it a point to have a paper map. It’s invaluable for getting the big picture, understanding alternate routes, and filling in when my phone runs out of juice. The free maps you get from your car-rental company usually don’t have enough detail. Look for the free Big Map (www.bigmap.is), which has a map of Reykjavík, including suburbs, on one side, and on the other, a serviceable map of the whole country. The free Around Iceland booklet includes maps of each region and of small towns. You could also buy a better map of the country in advance (they’re cheaper in the US—Michelin #750 is good), or pick one up (for a hefty 3,000 ISK) at a gas station, convenience store, or bookshop in Iceland.

Websites: Google Maps covers Iceland about as well as Europe or the US (though it occasionally gets Icelandic street names wrong and, as anywhere, it sometimes lacks detail). The Icelandic telephone directory website, www.ja.is, has more precise maps, but it’s less user-friendly; you can’t download the data, and it sometimes expects you to search for place names in an unusual format.

The “Road Info Viewer” at the Icelandic Road Authority website (www.road.is) is up-to-date and shows at a glance which stretches of road are paved and which are gravel. Click on “Layers,” then “Names” to show place names.

Exploring Iceland by car is a pleasure. Most of the main roads are paved and (outside Reykjavík) relatively uncrowded. But driving in Iceland does come with unique customs and hazards you should know about. A large percentage of serious car accidents in Iceland involve foreign tourists. The website www.drive.is has a helpful (if overlong) video introducing the basics. Remember to pack sunglasses for driving: The sun stays low in the Icelandic sky all year.

Road Rules: Be aware of typical European road rules; for example, Iceland requires headlights to be turned on at all times (usually an automatic feature in Icelandic cars), and forbids using a mobile phone without a hands-free headset. In Iceland, you’re not allowed to turn right on a red light, unless a sign or signal specifically authorizes it, and on expressways it’s illegal to pass drivers on the right. Even major highways like Highway 1 are predominantly two-lane, so remember to pass with care. Seat belts are required by law in Iceland for all passengers. Ask your car-rental company about these rules, or check the US State Department website (www.travel.state.gov, search for your country in the “Learn about your destination” box, then click on “Travel and Transportation”).

You may be stopped for a routine check by the police (be sure you have your rental paperwork close at hand).