25 Human Resource Management in Developing Countries

Introduction

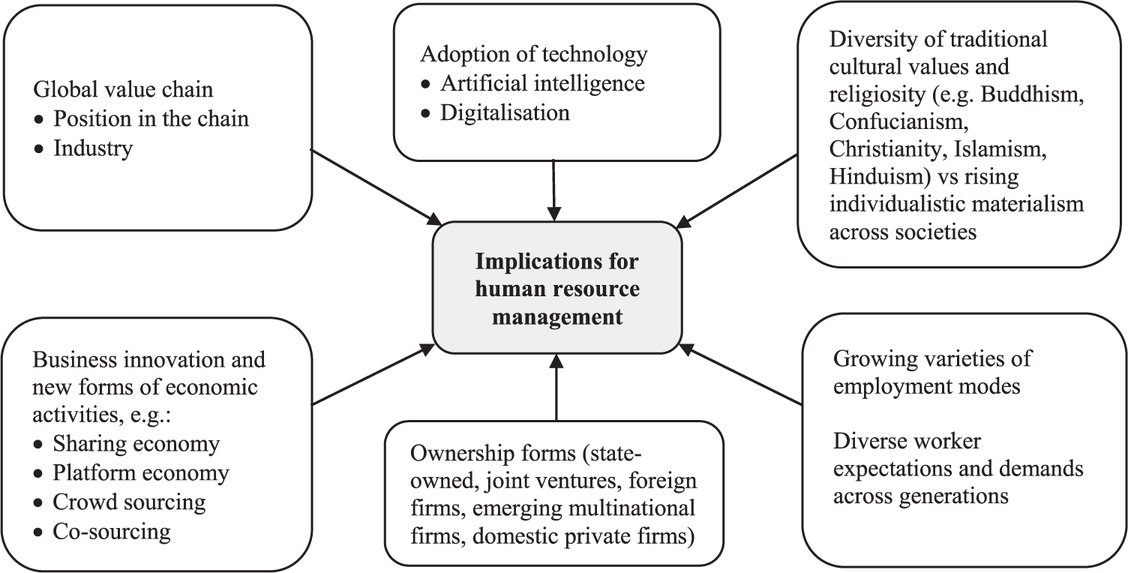

‘Developing countries’ (also known as less developed countries) cover a large population spanning several continents and regions with diverse cultural traditions. They also represent a constellation of sovereign states with markedly different political regimes, institutional arrangements, industrial structures, stages of economic development, and national strategies for global economic integration and social development.1 These diversities and distinctiveness underpin each nation's employment systems and human resource management (HRM) practices. While similar characteristics and HRM challenges may be evident across these nations, specific practices and solutions may differ at national and sub-national level. As it is impossible to cover HRM of all developing countries in one chapter, this chapter focuses mainly on the larger and relatively more developed economies within the developing country category, such as China, India, Malaysia, Vietnam, Russia and South Africa, and other emerging markets. It is important to note at the outset that the intention of this chapter is not to provide a definitive account of the characteristics of HRM of these countries (for more detailed country-specific discussion see Davila and Elvira, 2009; Horwitz and Budhwar, 2015; Budhwar and Mellahi, 2016; Cooke and Kim, 2018). Rather, it aims to outline pressures, features and developments experienced by these nations in the context of economic globalisation and technological transformation to identify key factors shaping the development of HRM in developing countries (see Figure 25.1). For the purpose of this chapter, the term ‘developing countries’ is used for general discussion, the terms ‘emerging economies’ and ‘transitional economies’ are also used to refer to the sub-groups of developing countries that are relatively more developed (emerging economies) or have transitioned from a former socialist regime towards a market economy system, notably in Eastern and Central Europe (transitional economies). As is often the case for a multi-country story, a level of over-simplification and over-generalisation is inevitable.

Figure 25.1 Examples of factors influencing HRM in developing countries

This chapter consists of six main sections in addition to this introduction and a conclusion. The first outlines some of the features of the political and institutional environment manifested in a number of developing countries. The second section examines diversity and disparity related to people management. This is followed by a summary of the general characteristics of HRM in developing countries, highlighting management mindsets, approaches, differences across ownership forms, as well as deficiencies of strategic HR capabilities. The fourth section assesses the role of premium cities and economic zones in developing countries and HRM implications. In the fifth section, we discuss the impact of technology on HRM. In the sixth section, we highlight a key challenge to HRM – talent shortages – encountered across developing countries. The chapter concludes by arguing that developing countries not only are diverse, but also may be leading in some aspects of technological, business and HRM innovations. These developments challenge existing concepts, theories and practices in HRM. A stereotypical approach to perceiving HRM in these countries should be avoided and some of the new developments found in these countries may be useful for other societal contexts.

Political and Institutional Environment

Political and institutional environments are a major factor in understanding HRM practices in developing countries. In fact, institutional context at various levels has been a key feature in studies of HRM in the international HRM field (e.g. Björkman and Welch, 2015; Budhwar, Varma and Patel, 2016; Cooke, Veen and Wood, 2017; Cooke, Wood, Wang and Veen, 2018). For developing countries, a relatively high level of political and economic risk, institutional flux and strong state intervention are some of the common characteristics, albeit the amount of variation in each characteristic may differ. National strategies and plans for development also differ. Changes in political and institutional environment have been a common feature in the last two to three decades as nation states became more open to the world economy and carried out reforms in response to domestic and international pressure (e.g. Budhwar and Mellahi, 2006; Kamoche, 2011; Cooke and Kim, 2018). How have the political and institutional conditions evolved in some of the developing countries? And how have these changes affected employment systems and HRM practices at national and sub-national level?

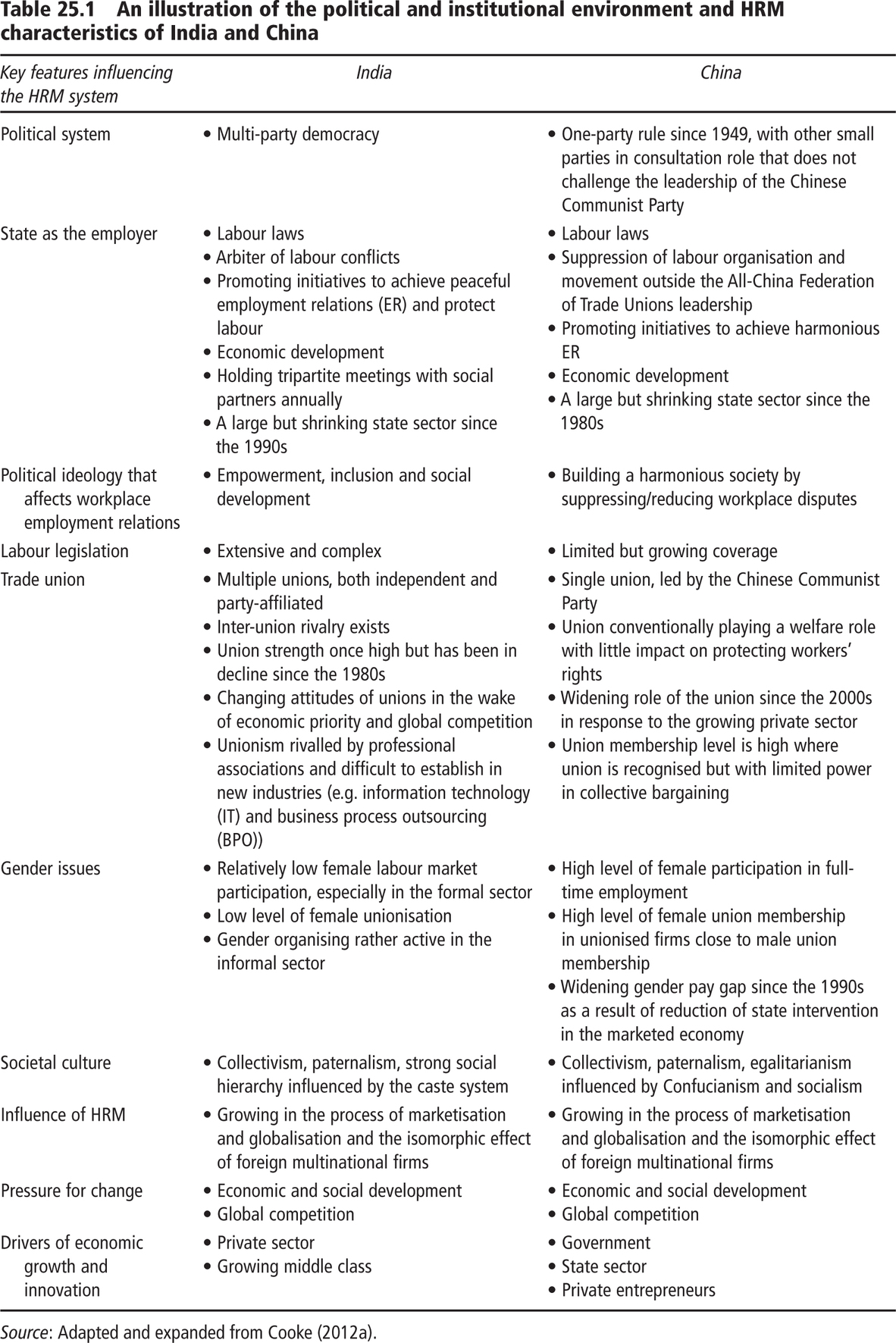

Take China and India, for example. These two most populated nations in the world are among the most studied developing countries in the HRM field, not least because of their rapid development and growing competitiveness in the global economy. However, the two countries display markedly different political and institutional systems (see Table 25.1), and some Western commentators have been puzzled as to why India, the most populated democratic country in the world, has not been economically more advanced than China, a one-party state. India gained its independence in 1947, two years ahead of the establishment of socialist China in 1949. India has a comprehensive, long-established, and what some would call over-complicated (World Bank, 2006; Bagga, 2013), legal system influenced by British colonialism. Compared with China, India has a language advantage in connecting with the world, as English is one of the official languages (second mother tongue) of the country. The Indian workforce is younger and the wage level is generally lower than those of China. Compared with China, India has a proportionally larger Western-educated elite who influence national economic policy. The rise of Indian economic and political influence has been less sanctioned by Western power. China opened up its economy in 1978 through its ‘open door policy’ (Huang, 2008), whereas India officially adopted its economic liberalisation policy in 1991, although economic reform started before then (Venkata Ratnam and Verma, 2011). India joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) at the beginning of 1995, whereas China accessed at the end of 2001, nearly seven years later. India has a much smaller state sector than China and, some would argue, a much more entrepreneurial and innovative private sector led by Western-educated organisational leaders (e.g. Khanna, 2007; Huang, 2008). As these points illustrate, developing countries often take different and unique roads to economic growth.

Source: Adapted and expanded from Cooke (2012a).

An important component of the institutional environment for national HRM and employment relations systems is labour regulation, in the form of legislation, administrative policy and voluntary regulation (e.g. trade union collective agreements). In some developing countries, such as India and South Africa, labour laws are relatively comprehensive compared with other developing countries (Cooke, 2012; Bagga, 2013). In other developing countries, such as China, it is the ineffective enforcement of labour laws, rather than their absence, that has been problematic in protecting workers’ rights and interests. If the slack enforcement of labour laws created opportunities for a low-cost manufacturing base drawing on the plentiful supply of labour and helped to propel China's economic growth from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, then this population dividend has been eroded since the mid-2000s (Cai, 2010). This is in part due to the declining growth rate of the population and the unwillingness of the younger generation to accept inferior employment terms and conditions. Recruitment and retention have become an ongoing problem for many employers (Cooke and Wang, 2018).

By contrast, the relatively strict labour laws in India and South Africa, and the comparatively strong union representation in the latter, have restricted the growth of formal employment in India (e.g. Venkata Ratnam and Verma, 2011) and incentivised employers in South Africa to hire illegal immigrants from other African countries with little, if any at all, employment protection. Such a practice has triggered resentment from (unemployed) South African nationals, blaming other African nationals for taking their jobs (e.g. BBC News, 2015). Compared with South Africa, trade unions in other African countries are relatively weak and the regulatory processes for collective bargaining and dispute resolution have been marked by their deficiency (Jackson, 2014). This institutional environment enables foreign multinational corporations (MNCs) to adopt a low-cost HR strategy, which often attracts criticism of exploitation of local workers and at times escalates into international political controversies (e.g. Wood and Horwitz, 2016). This suggests that weak institutions do not necessarily always benefit firms by adopting a low-cost HR strategy, as there may be hidden and unanticipated costs that may be damaging to the firm in the longer term.

Within the national setting, regulation and state policy do not affect firms of different ownership to the same extent. For example, state-owned enterprises in China have often been noted for holding (unfair) competitive advantage over firms of other ownership forms, including foreign MNCs, due to the strong institutional support of the former (e.g. Huang, 2008). However, such a ‘competitive’ edge may be lost, or indeed serve as a liability, when Chinese state-owned firms seek to expand globally and are opposed by various institutions. These include, for example, host-country government protectionism in the name of national security, trade union mobilisation to exert pressure on host governments, negative media coverage, and campaigns from national firms (e.g. Kragelund, 2009; Nyland, Forbes-Mewett and Thomson, 2011; Cooke, 2014). Therefore, the relationship between foreign MNCs and host-country institutions, at national and sub-national levels, is dynamic and interactive. In developing countries where institutional systems are evolving and regulatory power is weak, not only is the degree of autonomy and flexibility of firms’ HR policy and practice affected by the evolving and differentiated (e.g. across industrial sector and ownership forms) institutional environment, but also large firms/MNCs with strong bargaining power may pick and choose how they comply with local regulations and play an active role in co-shaping the institutional environment to their advantage (e.g. Child and Tsai, 2005).

Diversity and Disparity

Developing countries are diverse in their cultural traditions as well as the way these traditions influence social relations and HRM (e.g. Khan and Ackers, 2011; Warner, 2011; Rowley and Warner, 2013; Jackson, 2016). In Western countries, employers have encountered national diversity when operating in other countries or as a result of immigration. Diversity, inclusion and respecting religiosity and cultural beliefs are introduced into HR policy. However, this often falls short of providing policies and facilities to accommodate a range of religious and cultural activities/practices during work hours at the workplace. From the perspective of diversity in developing countries, the utility of diversity management that originates from the USA for other societal contexts is heavily criticised, not least for the gap between organisational rhetoric and practice (e.g. Nyambegera, 2011; Tatli and Özbilgin, 2012; Kirton, Robertson and Avdelidou-Fischer, 2016; Hennekam, Tahssain-Gay and Syed, 2017).

By contrast, in multicultural developing countries such as India, Malaysia and Sri Lanka, not only do public holidays reflect some of the major cultural traditions (e.g. Islamic, Hindu and Chinese festivals in Malaysia and Sinhalese, Buddhist, Tamil Thai and Christian festivals in Sri Lanka), but also companies may organise celebratory events and functions to mark the festive occasions. In some societies, ethnic, cultural and religious diversity has existed for centuries and is taken for granted, and research in India has revealed that indigenous employees do not necessarily embrace the US notion of diversity management as part of HRM (e.g. Cooke and Saini, 2012). Forstenlechner, Lettice and Özbilgin's (2012) case study of a finance company in the UAE that failed to improve demographic diversity of the workforce and employment equity by imposing a quota system, illustrates the limited transferability of US-developed diversity management initiatives to developing country contexts. In other Asian countries, such as China, India and Malaysia, affirmative policies and actions in the form of quotas, for example, have yielded some effect in raising gender and ethnic equality, despite the room for improvement that remains (e.g. Cooke, 2010; Tatli, Ozturk and Aldossari, 2018). These affirmative policies and actions, albeit resisted by employers to various degrees and in different disguises, have largely been initiated and imposed by the state, instead of being imported by foreign MNCs.

Nevertheless, diversity invariably leads to political, social and economic disparity at the macro level (e.g. Sheldon, Kim, Li and Warner, 2011; Nkomo, du Plessis, Haq and du Plessis, 2016; Wood and Cooke, forthcoming) and inequality at the organisational level (e.g. Mahadevan and Kilian-Yasin, 2017). In African post-colonial societies, for example, many inequalities derived from colonial periods remain and, in some cases, have widened or have been newly created (e.g. Médard, 2014; Kamoche and Siebers, 2015). As anti-colonialist writers (e.g. Fanon, 2008; Gibson, 2011) argued, colonialism has created long-lasting psychological effects on the colonised, engendering and embedding notions of inferiority, which prevent the achievement of workplace equality, allowing indigenous talents to fulfil their potential (see also Wood and Cooke, forthcoming). More broadly, the absence of fair treatment and labour rights, even when existing in principle, may be the norm at many workplaces in developing economies on the one hand (see below), but highly marketable individuals may be able to demand, some even dictate, their employment package on the other.

Characteristics of HRM in Developing Countries

Management mindsets and practices may be influenced, some more profoundly so than others, by cultural traditions. A critical notion for understanding the characteristics of HRM practices in developing countries is the organising principles for management. These include, for example, authority (e.g. level of control vs autonomy), chain of command (e.g. layers of hierarchy) and work organisation (e.g. level of flexibility required of employees). In general, developing countries have a relatively strict hierarchical system derived from social class (e.g. the caste system of India, ethnicity in Malaysia, the household registration system in China) and political positions (e.g. affiliation with political party and certain political/social groups). The hierarchical system is often replicated in the organisational structure through a long chain of commands. In addition, developing countries are largely paternalistic societies with authoritarian regimes, which means that there is limited workplace autonomy and empowerment (e.g. Cooke and Kim, 2018). For example, Witt and Redding (2013) revealed that workplace relationships in Asian countries are shaped by traditional hierarchical, collectivistic and masculine cultures. Similarly, Rowley, Bae, Horak and Bacouel-Jentjens (2017) observed that HRM in Asian countries is informed by paternalism, benevolence, collaboration and relationship (e.g. guanxi in the Chinese context). Since the level of institutionalised trust is relatively low, firms tend to rely heavily on informal arrangements to manage workplace relationships (e.g. Witt and Redding, 2013; Cooke, Wang and Wang, 2018).

Khan and Ackers’ (2011: 1330) study of HRM in the sub-Saharan African context revealed that ‘the broader social and moral issues of the wider community have a decisive influence on the employment relationship’ and that ‘internal employment relations structures, such as trade unions, do not constitute the main representative channels for employee grievances'. They questioned the suitability of a unitarist approach to HRM and called for the institutionalisation of some elements of the ‘African social system’ into ‘formal HRM policies and strategies', which is in line with the ‘neo-pluralist’ approach (2011: 1330).

Nevertheless, societies do not stand still. Economic development and competitive pressure have many traditional approaches to people management. In the search for competitive advantage and eagerness to catch up with the world economy, HRM in emerging economies (the relatively more developed group of developing countries) may be largely efficiency-driven, and informed by scientific management. For example, performance-related pay may be the norm in which a large proportion of an individual's wage is contingent upon their production output or sales. A dual staffing system may be employed where formal employees and workers on casual employment contracts (e.g. agency employment) may be working alongside each other, performing similar tasks, but with the latter receiving inferior employment packages compared with the former. Those hired in casual employment are often from lower social and economic backgrounds and, as a result, are disadvantaged in the labour market and workplace. Nevertheless, an increasing number of organisations, in China for example, are beginning to shift towards a more humanistic approach to managing people in order to improve productivity and retain talent (Min, Bambacas and Zhu, 2017).

Extant research on HRM in developing countries further identified that HRM practices differ considerably across ownership forms (e.g. Zhu, Collins, Webber and Benson, 2008; Poljašević, Ilić and Milunović, 2017; Cooke and Kim, 2018). In general, state-owned enterprises and smaller domestic private firms appear to retain a higher level of societal traditions and are less strategic in their approach to people management compared with foreign-invested MNCs, joint ventures and flagship domestic firms. Existing studies have also detected a level of convergence of types of HRM practices adopted across ownership forms as a result of globalisation and isomorphic effects, as firms search for more effective ways of managing their business to remain competitive (e.g. Cooke and Kim, 2018). While a deficiency in HR capacity and strategic HRM appears to be a shared feature across developing countries (e.g. Cooke, Wood and Horwitz, 2015; Fogarassy, Szabo and Poor, 2017; Cooke and Kim, 2018), MNCs, joint ventures and leading domestic firms fare better in general than state-owned and smaller private firms.

The Role of Premium Cities and Economic Zones in Developing Countries

HRM in developing countries has often been accentuated by their traditional peculiarities, which are attributed to their unique institutional and cultural influences (e.g. Kamoche, 2011; Warner, 2011; Budhwar and Mellahi, 2016; Rowley et al., 2017). However, it would be simplistic and naive to generalise these HRM practices as characteristic of a particular nation. Witt and Redding (2013) observed that a significant amount of intra-national diversity is found in developing economies in Asia that emerged during the period of rapid industrialisation and globalisation, with some areas developing faster than others. Similarly, Gong, Chow and Ahlstrom (2011) argued that cross-cultural differences may exist at the sub-national level due to the heterogeneity of the host-country culture. For example, two major cities in the same country may exhibit distinct cultural characteristics due to historical traditions and their local political environment, with different implications for HRM (e.g. Li, Tan, Cai, Zhu and Wang, 2013).

For many developing countries, there remain significant variations across regions within each of them, with regions in the coastal areas (easy access for export), national and provincial capitals and other premium cities in prime locations being far more developed than the rest of the country. In many cases, these municipalities are among the world-leading cities in certain aspects, showcasing the country's unique core strengths. These include, for example, Bangalore (India) as the Silicon Valley of India and the headquarters of several major state-owned corporations, Mumbai (India) as a financial, commercial, entertainment, IT outsourcing centre and headquarters of several leading Indian conglomerates, Johannesburg (South Africa) as an international financial centre and commercial hub, Shanghai (China) as an international financial and cultural centre, and Shenzhen (China), famous for its high-tech industry as the first economic special zone of the country.

Economic and technological factors are interrelated in shaping the economic profile of municipalities. For instance, in India, the IT and IT-enabled business process outsourcing (BPO)sectors are highly concentrated in a number of globally connected cities such as Bangalore, whereas Gurgaon is positioned as a multinational/international joint-venture manufacturing hub, Shanghai is a large commercial centre, whereas Dongguan (southern China) has been the centre of the ‘world factory’ (China). At a deeper level, the rapid development of these premium cities in recent decades has been shaped by the political, capital, technological and cultural logics and industrial heritage specific to each of them. In particular, the alliance of power between political and business elites, empowered by technology, determines what businesses the municipality may attract and become competitive in; such decisions are often influenced by their cognitive limitations and agenda. Thus, each city/region will have its own industrial clusters, investment environment, economic characteristics and labour market behaviour, which consequently shape HRM practices, including the capacity to attract and retain talent from other regions.

This is not to suggest, however, that the economic and social development policy and strategy would remain unchanged for each major municipality or region. In some situations, radical choices may be made that will lead to the disruption or discontinuation of the existing economic/business paradigm, with serious HR implications. The city of Dongguan mentioned above offers an interesting example here. Affected by a rising level of wage costs, declining number of manufacturing orders from global clients following the global financial crisis in 2008, and worsening environmental degradation as a result of industrial pollution, Dongguan's municipal government decided to change the industrial structure of the city, by introducing in the mid-2010s totally automated factories, forcing out highly polluting factories and attracting high-tech and high-revenue businesses into the city (e.g. People's Daily Online, 2015). As a result, the workforce of the city is shifting from one of predominantly less educated and semi-skilled (rural) migrant workers to a highly educated graduate workforce. An increasing number of factories that remain in the city are replacing their staff with industrial robots – a practice also occurring in other Chinese cities/regions. This has major implications for skill requirements, the nature of work, and employment outcomes. What skills would be required to facilitate the economic transition/transformation? Who would be responsible for developing the skills? Who would bear most of the cost of skill devaluation and job losses? How would institutional actors coordinate to develop skills and regulate the labour market? What is the role of governments? And what are the economic and labour market ripple effects of changes initiated by leading municipalities for the rest of the country that may reshape HRM at various levels?

Irrespective of the specific development plan of municipal governments and the policy and strategy associated with it, the rise of premium cities has benefited from favourable development policies, capital investments and human resources attracted to these places to improve their life prospects. As a result, these cities soak up a significant proportion of talent, through intra- and inter-country migration, leaving other less developed regions suffering from worsening skill shortages and a slower pace of development. Over-populated and with infrastructure development lagging behind, traffic congestion exacerbates the work–life conflict experienced by many workers who are already experiencing work intensification. Many of the workers are employed by companies whose business forms an integral part of the global value/supply chain, such as offshore BPO in the Indian and Philippine context and export manufacturing zone in the Chinese context. Workers in these sectors are often employed below their educational qualifications (for the BPO sector) and encounter poor employment terms and conditions, including job insecurity, low wages, limited social security benefits, and absence of career opportunities, exacerbated by a tightly monitored labour process (Beerepoot and Hendriks, 2013).

In response, workers vote with their feet or self-organise industrial action to demand better employment terms and conditions (Taylor, D'Cruz, Noronha and Scholarios, 2014). In industrial parks and economic special zones, industrial action is more easily organised due to the concentration of workers and sharing of information on closely knitted sites (e.g. Chan, 2011). For example, Chinese workers in the Honda (Nanhai) plant went on strike in 2010 and demanded, with success, improved terms and conditions. Other plants nearby followed suit afterwards and the labour movement soon gathered momentum nationally, forming the much reported Wave of 2010 Summer Strikes (Chang, 2013; Lüthje, 2014; Lyddon, Cao, Meng and Lu, 2015). The emergence of global cities, measured by financial power and high-tech infrastructure, and economic special zones as pioneer sites for global integration for developing countries therefore raises an important set of questions related to HRM in the broader context. For example, to what extent do the rise of these economic sites impact job opportunities and the labour process of workers in developed countries (e.g. Taylor and Bain, 2005)? To what extent do employers in developing countries have control over their HRM policy and practice at these production/service sites located on the lower rung of the global value chain? To what extent does workers’ employment outlook in these cities depend upon the economic and political climate of Western powers? And how may the international division of labour permeate these cities and impact the configuration of the local labour market, leading to the emergence of localised/regional HRM systems?

‘Individual’ refers to an employee while ‘Goal’ is not order in the narrow sense. Rather, it refers to user demand. ‘Individual–Goal Combination’ is to let employees and users unite into one entity, while ‘Win–Win’ manifests itself in employees realising their own value in the process of creating value for users. The Win–Win Model of Individual–Goal Combination fits in with the Internet Age. Its fundamental difference with the traditional management model is that the latter is constituted with the company at the centre while the former is user-centric. In the Internet Age information asymmetry shifts the balance in favour of the user and users can decide the fate of an enterprise. The only option for the enterprise is to catch up to the speed with which a user clicks the mouse. To be able to do this, front-line employees have to be given maximum autonomy and decision-making power, so that they can respond to the demands of users in the fastest way possible. The Win–Win Model of Individual–Goal Combination is to let employees become the principal in independent innovation, thereby forming a new pattern of relationship between the enterprise and employees. In other words, instead of employees following orders from the company as was the case in the past, employees now have to follow the demands of users, and the company in turn has to heed its employees’ plan to innovate on behalf of users. The essence of the Win–Win Model of Individual–Goal Combination is as follows: I create my own users and I share in the value I added. Effectively, the employee has autonomy to make decisions in light of the change in the market, and also has the right to determine his/her income in line with the value created for users.

Technology and HRM in Developing Countries

A common perception about developing countries is that they are relatively backward technologically compared with developed countries. However, a notable development in developing countries is the rapid development and adoption of new technology, particularly in premium cities, economic special zones, science parks and industrial parks. Some of their indigenous firms are learning from, and rapidly catching up with, developed countries, to some extent aided by nationals repatriated from developed economies (e.g. Liu, Lu, Filatotchev, Buck and Wright, 2010; Zweig and Wang, 2013; Kunasegaran, Ismail, Rasdi, Ismail and Ramayah, 2016). Some leading global firms headquartered in developing countries such as China and India may be more innovative than many firms in developed countries, taking advantage of new technological applications. Technological innovation is impacting HRM in developing countries in a variety of ways. Some emerging trends warrant discussion here.

One is the deployment of robotic automation technology that can replace low-skilled labour in the manufacturing sector. It is estimated that more than 60% and 73% of manufacturing workers in Indonesia and Thailand, respectively, are at risk of losing their salaried jobs owing to robotic automation (Chang, Rynhart and Huynh, 2016). In China alone, several million manufacturing jobs are expected to disappear in the next decade or so. For example, Foxconn, which employed around 1 million workers in China, has already installed 40,000 robots (called Foxbots) in its factories there and laid off some 60,000 employees in its Kunshan factory (near Shanghai) as of 2016 (Tencent, 2016). The garment industry is also heavily affected by technological change. The growing use of automation technology such as sewing robots is estimated to affect 86% and 88% of salaried textile workers in Vietnam and Cambodia, respectively (Chang et al., 2016). The garment industry of Sri Lanka and Mauritius, where the author has conducted fieldwork, also showed signs of a similar automation trend. The reasons for robotic automation in the manufacturing sector may differ slightly across countries. In China, rising wage levels, tightened labour regulation and recruitment difficulties in developed cities are some of the main reasons for automation. In Mauritius, some garment factories, which have traditionally relied heavily on recruiting temporary migrant workers from China and more recently from Muslim countries, introduced industrial robots because of the difficulties in recruiting skilled workers.

The impact of automation in developing countries should not be underestimated. According to McKinsey (2017: 8), automation will affect 1.1 billion employees globally, with China and India together accounting for ‘the largest technically automatable employment potential – more than 700 million full-time equivalents between them – because of the relative size of their labor forces'. The replacement of workers with industrial robots will be associated with the reduction of departments, managers and bureaucratic functions typical of the traditional management of factories. At the same time, it will generate new skill requirements, such as skills to operate and maintain robotic equipment.

Internet-based software technology also transforms the pattern of information sharing and economic transactions. The growth of e-commerce significantly impacts the mode of employment in the retail sector. Chang et al. (2016) noted that 85% and 88% of retail sector workers in Indonesia and the Philippines, respectively, are estimated to be at risk of losing their salaried jobs owing to automation and information technology. In this sector, the traditional mode of employment has shrunk, and non-standard employment has increased significantly, particularly in the form of self-employment. Software technology also seriously affects the BPO industry, where cloud computing and automation software undermine the viability of traditional business models. Chang et al. (2016) estimated that 89% of salaried workers in the Philippine BPO sector are exposed to the impact of this technological change.

Moreover, technological changes open up opportunities for digitally informed HR practices. We have now entered an era of ICT-enabled Big Data management in which personal data may be collected, often via third parties, with or without the implied consent of those concerned and aggregated through sophisticated data analytic techniques to identify patterns and trends to inform management solutions. For example, Walmart stores in China use customer flow information to determine their required staffing level by asking employees to work overtime at short notice or using part-time employees to cover peak periods. This means that workers have very little slack time during their shift period, and work is intensified. The implementation of annualised hours by Walmart (China) led to serious workforce protests in 2016 and 2017 (Xie and Cooke, 2018).

Huawei Technologies, a Chinese multinational, networking, telecommunications equipment and services company that came 83rd in the Fortune Global 500 in Fortune Magazine in 2017 (http://fortune.com/global500/huawei-investment-holding/), offers an interesting example in the use of mobile technology to provide tailored employee services. Huawei prides itself on providing fresh and delicious meals for its staff to keep them happy and motivated at work. It uses mobile technology to enable its employees to select their meals from a wide range of choices in advance and sends this information to the canteen so that it knows the level of demand for specific dishes. Huawei also informs its staff of peak times at the canteen so that they can adjust their meal times to avoid wasting time in the queue. This is considered a win–win solution for both the company and the staff, as both are making the best use of employees’ time to increase productivity or maximise rest time.

Perhaps a more alarming example is the taxi companies that use taxi-calling software (similar to that of Uber) in manufacturing zones or business/industrial parks in developed cities in China to provide aggregate information related to the workers’ movements. This includes, for example, which taxi-calling software workers from particular companies like to use; when they finish work; how many hours of overtime they work; where they like to go for their social life/entertainment; how far they travel for their social life; and the average amount they spend on taxis per week (Luo, 2016). In countries like China, where IT is developing fast but data protection regulation is lagging behind, it is unclear what direction this may take in terms of data mining and analytics that may be used for HRM and what impact this may have on employees. However, it is clear that information can be gathered and analysed by the employer or third party, which can be used to understand employee preferences and movements and inform HRM decisions, including benchmarking against competitor firms.

Talent Shortages as a Key Challenge

A number of challenges related to HRM have been revealed in the foregoing discussion, including, for example, inequality, weak HR capacities, talent shortage and so forth (see also Cooke et al., 2015). In this section, we analyse further the talent shortage problem because of the significance of human capital to national development. Although talent management is a universal problem, in developing countries, and especially the least developed countries, talent shortage problems are far more pronounced than in developed countries and regions. Such a bottleneck is undermining the development aspirations of these nations (e.g. Amankwah-Amoah and Debrah, 2011; Banya and Zajda, 2015). Talent shortages in developing countries may be attributed to several main reasons.

The first and most fundamental reason is the mismatch between what is supplied through the education and vocational training system and what employers demand (e.g. Cooke, Saini and Wang, 2014). For example, as one of the world's largest economies, China only ranked 54th out of 118 countries in the Global Talent Competitiveness Index 2017 (Lanvin and Evans, 2017), and ranked 64th out of 124 countries in the Human Capital Index 2015 (World Economic Forum, 2015). Employer discrimination along the lines of gender (e.g. Sovanjeet, 2014), physical ability (e.g. Kulkarni and Scullion, 2015), ethnicity and migration status (e.g. Crowley-Henry and Ariss, 2016) further exacerbate the talent shortage problem. This suggests that employers in developing countries should adopt a fair and inclusive approach to HRM in order to attract and retain talent from all sorts of backgrounds and with different demographic characteristics.

A second related reason is that disruptive technological innovations and the growing use of industrial robots have raised new skill requirements, as discussed earlier. According to McKinsey (2017), by 2030 an estimated 800 million jobs will be replaced by robots globally, and in China there will be a shortage of 5 million people who specialise in artificial intelligence. It is unclear what plan is being developed by the state to combat such a large skills gap.

A third reason is that while developing countries generally have a young population (e.g. Ghana, India, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, Turkey and Vietnam) and therefore workforce compared with developed countries, population ageing is occurring in several emerging economies (Argentina, Brazil, China and Russia). In countries that are experiencing population ageing, the population dividend that once fuelled their economic growth is declining (e.g. Cai, 2010). The decline in the proportion of the younger generation in the population also means that the relatively well-educated segment of the workforce is in high demand, leading to talent retention problems and wage inflation (Nankervis, Cooke, Chatterjee and Warner, 2013).

A fourth related reason is talent mobility across organisations and regions domestically and across countries internationally. Existing studies have shown a relatively high level of job hopping among talented employees, especially in high-tech industries and the BPO sector (e.g. Thite and Russell, 2010). At the country level, the brain drain as a result of transnational migration from less developed to more developed countries and regions further exacerbates talent shortage problems in poor countries and regions, particularly in Africa and in South and Southeast Asia (e.g. Song and Song, 2015; Jackson and Horwitz, 2018; Vaiman, Schuler, Sparrow and Collings, 2018; Wood and Cooke, forthcoming). For example, Khilji and Keilson's (2014) study provided a detailed account of state policy interventions in the last three decades including education reforms, youth programmes, citizenship policies for its diaspora, and so forth, in the three southern Asia states of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, where the population is relatively young and with limited access to formal education. Their study highlights the ‘prevalence of the paradox of development and retention particularly in Bangladesh and Pakistan, where youth is also being trained to emigrate’ (Khilji and Keilson, 2014: 114). Although repatriation of talented nationals has been occurring to various extents in developing countries, problems associated with repatriation have been widely reported (e.g. Zweig and Wang, 2013; Singh and Krishna, 2015). For example, Kunasegaran et al.'s (2016: 370) study of repatriates in the Malaysian context revealed that, while returning managers are ‘very much in demand', organisational support is essential to the successful adaptation of the returnees to their repatriated life and work.

Conclusion

This chapter outlined the institutional and cultural contexts of developing countries within which HRM characteristics, practices and challenges can be understood. It is clear that HRM systems in developing countries are evolving, even being transformed in some countries. There is a discernible trend, in China for example, of re-recognising the traditional cultural values in managing people and workplace relationships. At the same time, businesses are moving towards adopting flexible/informal employment models to support their new business models in pursuit of competitive advantage. How compatible are the two management mindsets/approaches? Does this suggest business leaders are engaging in trial and error management? Or is it an attempt to exploit workers further through moral sanctions and paternalistic superiority?

It is also clear that new digital business models and digitalised business processes are emerging in developing countries. These changes are not only displacing jobs (e.g. through automation) but also creating new jobs, new skill requirements and new ways of working which have profound impacts on the HR function, people management and human capital development. These developments raise fundamental questions that have implications for strategic HRM concepts, theories and practices, challenge their relevance, and call for new developments in these areas that will also have relevance to the developed country context. It is important to reiterate that developing countries vary widely in their educational and technological capabilities and levels of economic and technological development. These disparities may widen even further as these nations continue to develop at different speeds within the constraints of domestic conditions.

New business models and new ways of work organisation and deployment of human capital, aided by the growing use of digitalisation, Big Data analytics, and the use of artificial intelligence, coupled with the lagging behind of labour regulation in response to these developments, mean that opportunities for workers in developing countries are not evenly spread. The International Labour Organization (2017) draws our attention to the question of what kind of future work we want against a context of digitalisation and robotisation in workplaces. What kind of voice do workers in developing countries have in shaping their future of work? Does technological innovation reduce work intensity and working hours in developing countries where capital generally has more bargaining power than workers? How can working time be regulated to prevent work from encroaching further upon non-work time? And how can the informalisation of employment and deterioration of job quality be prevented more broadly? These are some of the realistic but challenging questions that confront policy-makers and researchers.

In summary, this chapter highlights a number of key features of HRM and their developments in developing countries. The intention of the chapter was not to provide a definitive account of HRM in all these countries – an impossible mission given the diversity and uniqueness of each nation and regional differences within nations. On the contrary, the chapter aimed to make two arguments in an attempt to avoid providing a stereotypical picture and broad brush description of the characteristics of HRM practices in developing countries. First, developing countries are not of one type – there are continuing (and even growing) diversity and divergence among them. Therefore HRM in developing countries needs to be examined and understood with a greater level of sensitivity and nuance than currently granted. To do this, more attention may need to be given to qualitative research in order to discover in more depth what is really going on in these countries and regions, why, and so what? Second, while global economic integration continues to develop as a general trend, developing countries are not necessarily lagging behind developed countries on all fronts in their economic and technological development, at least for the emerging economies that are fast catching up and taking global leadership positions in certain areas. As the relative economic power of Western countries declines and the utility of their business and HRM models for developing countries is called into question (e.g. Afiouni, Ruël and Schuler, 2013), will models conceived in developing countries be able to offer alternative solutions? At least the new developments found in developing countries may serve as lessons for developed countries.

Note

1 See United Nations (2014) for a list of developing countries and International Monetary Fund (2015) for selected economic and financial facts of developing countries.

References

, and (2013) HRM in the Middle East: Toward a greater understanding, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(2): 133–143.

and (2011) Competing for scarce talent in a liberalized environment: Evidence from the aviation industry in Africa, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22: 3565–3581.

(2013) Why Indian talent is going to waste, Human Resource Management International Digest, 21(2): 3–4.

and (2015) Globalization, the brain drain, and poverty reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa, in J. Zajda (ed.) Second International Handbook on Globalisation, Education and Policy Research. Dordrecht: Springer.

BBC News (176 April 2015) South Africa's Durban City rallies against xenophobia. www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-32332744, accessed on 10 February 2018.

and (2013) Employability of offshore service sector workers in the Philippines: Opportunities for upward labour mobility or dead-end jobs? Work, Employment and Society, 27(5): 823–841.

and (2015) Framing the field of international human resource management research, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(2): 136–150.

Budhwar, P. and Mellahi, K. (2006) (eds) Managing Human Resources in the Middle East. London: Routledge.

Budhwar, P. and Mellahi, K. (2016) (eds) Handbook of Human Resource Management in the Middle East. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

, and (2016) Convergence-divergence of HRM in Asia: Context-specific analysis and future research agenda, Human Resource Management Review, 26: 311–326.

(2010) Demographic transition, demographic dividend, and Lewis turning point in China, China Economic Journal, 3(2): 107–119.

(2011) Strikes in China's export industries in comparative perspective, China Journal, 65: 27–51.

, and (2016) ASEAN in Transformation: How Technology is Changing Jobs and Enterprises (No. 994909343402676). Geneva: International Labour Organization.

(2013) Legitimacy and the legal regulation of strikes in China: A case study of the Nanhai Honda strike, International Journal of Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations, 29: 133–144.

and (2005) The dynamic between firms’ environmental strategies and institutional constraints in emerging economies: Evidence from China and Taiwan, Journal of Management Studies, 42(1): 95–125.

(2010) Women's participation in employment in Asia: A comparative analysis of China, India, Japan and South Korea, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(10–12): 2249–2270.

(2012) Employment relations in China and India, in M. Barry and A. Wilkinson (eds) Edward Elgar Handbook of Comparative Employment Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 184–213.

(2014) Chinese multinational firms in Asia and Africa: Relationships with institutional actors and patterns of employment practices, Human Resource Management, 53(6): 877–896.

Cooke, F.L. and Kim, S.H. (eds) (2018) Routledge Handbook of Human Resource Management in Asia. London: Routledge.

and (2012) Managing diversity in Chinese and Indian firms: A qualitative study, Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 3(1): 16–32.

, and (2014) Talent management in China and India: A comparison of management perceptions and human resource practices, Journal of World Business, 49(2): 225–235.

, and (2017) What do we know about cross-country comparative studies in HRM? A critical review of literature in the period of 2000-2014, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(1): 196–233.

and (2018) Macro-level talent management in China, in V. Vaiman, R. Schuler, P. Sparrow and D. Collings (eds) Macro Talent Management. London: Routledge.

, and (2018) State capitalism in construction: Staffing practices and labor relations in Chinese construction firms in Africa, Journal of Industrial Relations, 60(1): 77–100.

, and (2015) Multinational firms from emerging economies in Africa: Implications for research and practice in human resource management, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(21): 2653–2675.

, , and (2018) How far has international HRM travelled? A systematic review of literature on multinational corporations (2000-2014), Human Resource Management Review, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.05.001

and (2016) Talent management of skilled migrants: Propositions and an agenda for future research, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(13): 2054–2079.

and (2009) Best Human Resource Management Practices in Latin America. London: Routledge.

(2008) Black Skin, White Masks. London: Pluto Press.

, and (2017) Critical issues of human resource planning, performance evaluation and long-term development on the central region and non-central areas: Hungarian case study for investors, International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 9(1): 1–9.

, and (2012) Questioning quotas: Applying a relational framework for diversity management practices in the United Arab Emirates, Human Resource Management Journal, 22(3): 299–315.

(2011) Fanonian Practices in South Africa: From Steve Biko to Abahlali baseMjondolo. Scottsville: University of Kwazulu Natal Press.

, and (2011) Cultural diversity in China: Dialect, job embeddedness, and turnover, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(2): 221–238.

, and (2017) Contextualising diversity management in the Middle East and North Africa: A relational perspective. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3): 459–476.

Horwitz, F.M. and Budhwar, P. (eds) (2015) Handbook of Human Resource Management in Emerging Markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

(2008) Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Labour Organization (2017) The Future of Work We Want: A Global Dialogue. www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/dialogue/WCMS_570282/lang–en/index.htm, accessed on 2 September 2018.

International Monetary Fund (April 2015) World Economic Outlook: Uneven Growth – Short- and Long-Term Factors. Washington, DC.

(2014) Employment in Chinese MNCs: Appraising the dragon's gift in Sub-Saharan Africa, Human Resource Management, 53(6): 897–919.

(2016) Cross-cultural issues in HRM in emerging markets, in F. M. Horwitz and P. Budhwar (eds) Handbook of Human Resource Management in Emerging Markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 42–67.

and (2018) Expatriation in Chinese MNEs in Africa: An agenda for research, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(11): 1856–1878.

(2011) Introduction: Human resource management in Africa, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(7): 993–997.

and (2015) Chinese investments in Africa: Toward a post-colonial perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(21): 2718–2743.

and (2011) Neo-pluralism as a theoretical framework for understanding HRM in sub-Saharan Africa, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(7): 1330–1353.

(2007) Billions of Entrepreneurs: How China and India are Reshaping Their Future – and Yours. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

and (2014) In search of global talent: Is South Asia ready? South Asian Journal of Global Business Research, 3(2): 114–134.

, and (2016) Valuing and value in diversity: The policy-implementation gap in an IT firm, Human Resource Management Journal, 26(3): 321–336.

(2009) Knocking on a wide-open door: Chinese investments in Africa, Review of African Political Economy, 36(122): 479–497.

and (2015) Talent management activities of disability training and placement agencies in India, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(9): 1169–1181.

, , , and (2016) Talent development environment and workplace adaptation: The mediating effects of organisational support, European Journal of Training & Development, 40(6): 370–389.

and (2017) The Global Talent Competitiveness Index 2017: Talent and Technology. Fontainebleau: INSEAD.

, , , and (2013) Regional differences in a national culture and their effects on leadership effectiveness: A tale of two neighboring Chinese cities, Journal of World Business, 48(1): 13–19.

, , , and (2010) Returnee entrepreneurs, knowledge spillovers and innovation in high-tech firms in emerging economies, Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7): 1183–1197.

(2016) What time does Foxconn's staff finish work? DD (taxi-calling platform) says it knows, 6 September, Internet source: http://m.jiemian.com/article/839269.html?from=timeline&isappinstalled=0.

(2014) Labour relations, production regimes and labour conflicts in the Chinese automotive industry, International Labour Review, 153(4): 535–560.

, , and (2015) A strike of ‘unorganised’ workers in a Chinese car factory: The Nanhai Honda events of 2010, Industrial Relations Journal, 46(2): 134–152.

and (2017) Dominant discourse, orientalism and the need for reflexive HRM: Skilled Muslim migrants in the German context, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(8): 1140–1162.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017) A Future That Works: Automation, Employment, and productivity. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Global%20Themes/Digital%20Disruption/Harnessing%20automation%20for%20a%20future%20that%20works/MGI-A-future-that-works-Executive-summary.ashx, accessed on 12 December 2017.

(2014) Patrimonialism, neo-patrimonialism and the study of the post-colonial state in Subsaharan Africa, Occasional Paper, Rosskilde University, 17: 76–97.

, and (2017) Strategic Human Resource Management in China: A Multiple Perspective. London: Routledge.

, , and (2013) New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India. London: Routledge.

, , and (2016) Diversity, employment equity policy and practice in emerging markets, in F. M. Horwitz and P. Budhwar (eds) Handbook of Human Resource Management in Emerging Markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 195–224.

(2011) Ethnicity and human resource management practice in sub-Saharan Africa: The relevance of the managing diversity discourse, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(7): 1077–1090.

, and (2011) Sinophobia as corporate tactic and the response of host communities, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 41(4): 610–631.

People's Daily Online (15 July 2015) First unmanned factory takes shape in Dongguan City. http://en.people.cn/n/2015/0715/c90000-8920747.html, accessed on 15 April 2018.

, and (2017) Ownership structure of the organisation as a determinant of human resource management in the context of transition countries, Acta Economica, 15(26): 75–102.

and (2004) Co-creating unique value with customers, Strategy & Leadership, 32(3): 4–9.

, , and (2017) Distinctiveness of human resource management in the Asia Pacific region: Typologies and levels, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(10): 1393–1408.

Rowley, C. and Warner, M. (2013) (eds) Whither South East Asian Management? The First Decade of the New Millennium. London: Routledge.

Sheldon, P., Kim, S., Li, Y. and Warner, M. (2011) (eds) China's Changing Workplace: Dynamism, Diversity and Disparity. London: Routledge.

and (2015) Trends in brain drain, gain and circulation: Indian experience of knowledge workers, Science Technology & Society, 20(3): 300–321.

and (2015) Why do South Korea's scientists and engineers delay returning home? Renewed brain drain in the new millennium, Science Technology & Society, 20(3): 349–368.

(2014) HR issues and challenges in pharmaceuticals with special reference to India. Review of International Comparative Management, 15(4): 423–430.

and (2012) An emic approach to intersectional study of diversity at work: A Bourdieuan framing, International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(2): 180–200.

, and (2018) Equal opportunity and workforce diversity in Asia, in F.L. Cooke and S.H. Kim (eds) Routledge Handbook of Human Resource Management in Asia, London: Routledge, pp. 256–272.

and (2005) India calling to the far away towns: The call centre labour process and globalization, Work, Employment and Society, 19(2): 261–282.

, , and (2014) From boom to where? The impact of crisis on work and employment in Indian BPO, New Technology, Work and Employment, 29(2): 105–123.

Tencent (2016) Production Workers are Going to Cry: Foxconn Newly Installed 40,000 Robots in China. http://tech.qq.com/a/20161006/009459.htm, accessed on 7 October, 2018.

and (2010) Work organization, human resource practices and employee retention in Indian call centres, Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 48(3): 356–374.

United Nations (2014) Country classification. www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_country_classification.pdf, accessed on 13 January 2018.

Vaiman, V., Schuler, R., Sparrow, P. and Collings, D. (eds) (2018) Macro Talent Management. London: Routledge.

and (2011) Employment relations in India, in G. Bamber, R. Lansbury and N. Wailes (eds) International and Comparative Employment Relations, 5th edn. London: Sage, pp. 330–352.

Warner, M. (ed.) (2011) Confucian HRM in Greater China: Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

and (2013) Asian business systems: Institutional comparison, clusters and implications for varieties of capitalism and business systems theory, Socio-Economic Review, 11(2): 265–300.

and (forthcoming) Talent management in Africa, in I. Tarique (ed.) The Routledge Companion to Talent Management. London: Routledge.

and (2016) Theories and institutional approaches to HRM and employment relations in selected emerging markets, in F.M. Horwitz and P. Budhwar (eds), Handbook of Human Resource Management in Emerging Markets. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 19–41.

World Bank (2006) India Country Overview 2006. http://worldbank.org, accessed on 16 March 2007.

World Economic Forum (2015) The Human Capital Report. www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Human_Capital_Report_2015.pdf, accessed on 18 November 2017.

and (2018) From quality to cost? The evolution of Walmart's business strategy and human resource practices in China and their impact on industrial relations (1996–2016), Human Resource Management. Available at https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21931

, , and (2008) New forms of ownership and human resource management in Vietnam, Human Resource Management, 47(1): 157–175.

and (2013) Can China bring back the best? The Communist Party organizes China's search for talent, China Quarterly, 215: 590–615.