to the Tirupp

vai

vai vai

vaiIf one were to evoke classical Tami poetic paradigms of the interior (akam) and exterior (pu

poetic paradigms of the interior (akam) and exterior (pu am), then the Tirupp

am), then the Tirupp vai moves from the external worlds inhabited by the gop

vai moves from the external worlds inhabited by the gop s, pausing at the threshold of their homes, but not quite entering there. That voyage into the interior, into the heart as it were, is reserved for K

s, pausing at the threshold of their homes, but not quite entering there. That voyage into the interior, into the heart as it were, is reserved for K

a’s mansion (verses 16–30), where

a’s mansion (verses 16–30), where

(in the gop

(in the gop persona, according to various commentators) and her companions make a tantalizing journey into the very interior of K

persona, according to various commentators) and her companions make a tantalizing journey into the very interior of K

a’s home. But the Tirupp

a’s home. But the Tirupp vai seems to assert that the bold entry into the heart of the matter as it were can only be accomplished with companions, even if some of them are less than eager to wake up at the crack of dawn and venture to bathe in the freezing waters of the local pond. The “waking up of the gop

vai seems to assert that the bold entry into the heart of the matter as it were can only be accomplished with companions, even if some of them are less than eager to wake up at the crack of dawn and venture to bathe in the freezing waters of the local pond. The “waking up of the gop s” section of the Tirupp

s” section of the Tirupp vai in essence is addressed not to just the characters of the poem. Each listener/reader becomes a gop

vai in essence is addressed not to just the characters of the poem. Each listener/reader becomes a gop who has slept too late and has forgotten how easy it might be to win K

who has slept too late and has forgotten how easy it might be to win K

a for herself; or is too absorbed in K

a for herself; or is too absorbed in K

a and has forgotten the importance of fellow devotees, an interpretation that dominates the exegetical discourse around the Tirupp

a and has forgotten the importance of fellow devotees, an interpretation that dominates the exegetical discourse around the Tirupp vai, beginning with Periyav

vai, beginning with Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai in the thirteenth century. Curiously, despite being anachronistic, later commentarial traditions identify each of the sleeping gop

ai in the thirteenth century. Curiously, despite being anachronistic, later commentarial traditions identify each of the sleeping gop s of this section with a particular

s of this section with a particular

v

v r (or alternately,

r (or alternately,  c

c rya). For example, in verse 7 P

rya). For example, in verse 7 P y

y

v

v r is imagined as being awakened because the girl is addressed as p

r is imagined as being awakened because the girl is addressed as p ype

ype

(refer to the note for Tirupp

(refer to the note for Tirupp vai 7 for a listing of the

vai 7 for a listing of the

v

v r verse concordances in the text).

r verse concordances in the text).

Although the vow in the Tirupp vai takes place in M

vai takes place in M rka

rka i (December–January), the quest for K

i (December–January), the quest for K

a is presented as timeless, and the poem describes the path to K

a is presented as timeless, and the poem describes the path to K

a as well as becomes the path to K

a as well as becomes the path to K

a. When finally all of the girls have been gathered, the gop

a. When finally all of the girls have been gathered, the gop s (and all the audience of the poem imagining themselves as gop

s (and all the audience of the poem imagining themselves as gop s) approach K

s) approach K

a in his house to awaken him and his family there. The last section of the poem is a gradual and provocative entry into the god’s inner world—one might almost imagine, entering a temple, moving past the door—guardians (dv

a in his house to awaken him and his family there. The last section of the poem is a gradual and provocative entry into the god’s inner world—one might almost imagine, entering a temple, moving past the door—guardians (dv rap

rap las), and the directional deities (dikp

las), and the directional deities (dikp las), until one reaches the sacred womb—where the great god awaits. Here, the gop

las), until one reaches the sacred womb—where the great god awaits. Here, the gop s pause at the very threshold of K

s pause at the very threshold of K

a’s bedroom, peering in, asking to be let in. When they finally do gaze upon K

a’s bedroom, peering in, asking to be let in. When they finally do gaze upon K

a, it is to witness a moment of profound intimacy: K

a, it is to witness a moment of profound intimacy: K

a is with his wife Nappi

a is with his wife Nappi

ai, the woman for whom he subdued the seven bulls. It is this intimacy, and it is just such a special place that the gop

ai, the woman for whom he subdued the seven bulls. It is this intimacy, and it is just such a special place that the gop girls desire, and indeed boldly claim in the penultimate verse of the Tirupp

girls desire, and indeed boldly claim in the penultimate verse of the Tirupp vai (29).

vai (29).

In the general introduction to each of the three sections of the poem, I discuss

’s use of the categories of akam (interior) and pu

’s use of the categories of akam (interior) and pu am (exterior) in the Tirupp

am (exterior) in the Tirupp vai. In the N

vai. In the N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i, time (for example, dream time, mythic time, poetic time) and space (for example, interior/exterior, mythic, geographic) constantly intersect and collide to create a fluid, non-linear and, in many ways-disorienting narrative. In the introduction, I have unpacked the play of interior and exterior places/time, mythic and dream spaces/time, contrasting their use in the Tirupp

i, time (for example, dream time, mythic time, poetic time) and space (for example, interior/exterior, mythic, geographic) constantly intersect and collide to create a fluid, non-linear and, in many ways-disorienting narrative. In the introduction, I have unpacked the play of interior and exterior places/time, mythic and dream spaces/time, contrasting their use in the Tirupp vai and N

vai and N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i.

i.

The Tirupp vai has a rich and very deep history of

vai has a rich and very deep history of  r

r vai

vai

ava commentary, rivaling that of Namm

ava commentary, rivaling that of Namm

v

v r’s Tiruv

r’s Tiruv ymo

ymo i. The most significant of the Tirupp

i. The most significant of the Tirupp vai commentaries, composed in the hybrid commentarial prose language Ma

vai commentaries, composed in the hybrid commentarial prose language Ma iprav

iprav

a, are Periyav

a, are Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai’s M

ai’s M v

v yirappa

yirappa i, the

i, the  r

r yirappa

yirappa i of A

i of A akiya Ma

akiya Ma av

av

a Perum

a Perum

N

N ya

ya

r, the N

r, the N l

l yirappa

yirappa i and the

i and the  r

r yirappa

yirappa i. In addition, Ra

i. In addition, Ra gar

gar m

m nuja composed an important Sanskrit commentary to the Tirupp

nuja composed an important Sanskrit commentary to the Tirupp vai. Several contemporary traditional scholars of the two major

vai. Several contemporary traditional scholars of the two major  r

r vai

vai

ava schools have added to this collection of Tirupp

ava schools have added to this collection of Tirupp vai commentaries. These include Uttamur Veeraraghavachariar and Annangarachariar, among others. In addition, one can find any number of Tirupp

vai commentaries. These include Uttamur Veeraraghavachariar and Annangarachariar, among others. In addition, one can find any number of Tirupp vai explications composed in Tami

vai explications composed in Tami and English by lay practitioners who have a lifelong love for this text.

and English by lay practitioners who have a lifelong love for this text.

Similar to other

v

v r poems, traditional commentaries identify two layers of meaning in the Tirupp

r poems, traditional commentaries identify two layers of meaning in the Tirupp vai. The first layer is referred to as any

vai. The first layer is referred to as any pade

pade

rtha (literal meaning), while the second meaning is known as sv

rtha (literal meaning), while the second meaning is known as sv pade

pade

rtha (esoteric meaning). According to this framework, to grasp just the any

rtha (esoteric meaning). According to this framework, to grasp just the any pade

pade a meaning of a poem is to miss the point. In unpacking a poem’s esoteric meanings, the commentator skillfully incorporates into his interpretations the qualified non-dualist philosophy (vi

a meaning of a poem is to miss the point. In unpacking a poem’s esoteric meanings, the commentator skillfully incorporates into his interpretations the qualified non-dualist philosophy (vi i

i

dvaita) of R

dvaita) of R m

m nuja, especially as it pertains to the role of the teacher or other mediators in guiding one’s surrender to god, the nature of god’s grace, and what the very act of surrender constitutes.

nuja, especially as it pertains to the role of the teacher or other mediators in guiding one’s surrender to god, the nature of god’s grace, and what the very act of surrender constitutes.

The recitation of the names of Vi

u (Hari n

u (Hari n masa

masa k

k rtana) is a central theme in the Tirupp

rtana) is a central theme in the Tirupp vai and is referred to in verses 2–3, 5–8, 11–16, and 25. The commentators also stress the efficacy of this mode of worship and offer a few detailed comments on the idea in Tirupp

vai and is referred to in verses 2–3, 5–8, 11–16, and 25. The commentators also stress the efficacy of this mode of worship and offer a few detailed comments on the idea in Tirupp vai 2. The commentaries to the Tirupp

vai 2. The commentaries to the Tirupp vai are rich in allusions to epic and Pur

vai are rich in allusions to epic and Pur

ic sources, namely the R

ic sources, namely the R m

m ya

ya a, the Bhagavad G

a, the Bhagavad G t

t , and the Bh

, and the Bh gavata Pur

gavata Pur

a. In addition, the commentators also reference other

a. In addition, the commentators also reference other

v

v r poets like Namm

r poets like Namm

v

v r. Allusions to and quotations from any other Tami

r. Allusions to and quotations from any other Tami literary sources are quite rare.

literary sources are quite rare.

These notes are meant to offer a taste of the craft of  r

r vai

vai

ava exegesis. They are not a translation of any single commentary. Rather, they represent a synthesis of the major interpretations associated with the Tirupp

ava exegesis. They are not a translation of any single commentary. Rather, they represent a synthesis of the major interpretations associated with the Tirupp vai verses, while still pointing out differences in interpretation. I have relied on the following commentators who wrote in Ma

vai verses, while still pointing out differences in interpretation. I have relied on the following commentators who wrote in Ma iprav

iprav

a and Tami

a and Tami —Periyav

—Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai, Uttamur Veeraraghavachariar, Annangarachariar, and Srinivasa Aiyyankar Swami. In English, I have relied on C. Jagannathachariar and Oppiliappan Sri Varadachari Sathakopan. In the notes below, I clearly indicate where I follow the commentators by referring to them individually or as a group. Where there is no such marker, the interpretation is my own.

ai, Uttamur Veeraraghavachariar, Annangarachariar, and Srinivasa Aiyyankar Swami. In English, I have relied on C. Jagannathachariar and Oppiliappan Sri Varadachari Sathakopan. In the notes below, I clearly indicate where I follow the commentators by referring to them individually or as a group. Where there is no such marker, the interpretation is my own.

Note: In the notes below I have used K

a and Vi

a and Vi

u-N

u-N r

r ya

ya a interchangeably. In the Tirupp

a interchangeably. In the Tirupp vai,

vai,

does not make a clear distinction between these two forms and in fact frequently equates the two. The commentators follow her lead and use K

does not make a clear distinction between these two forms and in fact frequently equates the two. The commentators follow her lead and use K

a and Vi

a and Vi

u-N

u-N r

r ya

ya a as synonyms.

a as synonyms.

Tirupp vai 1–5: A General Introduction

vai 1–5: A General Introduction

The first five verses of the Tirupp vai are referred to as p

vai are referred to as p yiram (preface) or mah

yiram (preface) or mah prave

prave am (grand entry). In these introductory stanzas, the poem introduces the p

am (grand entry). In these introductory stanzas, the poem introduces the p vai n

vai n

pu, the vow the young gop

pu, the vow the young gop girls of

girls of  yarp

yarp

i are about to undertake. As such, it lays out the time of the year that this vow is practiced, the goal of this vow, its requirements, and its benefits (see introduction for a discussion of the p

i are about to undertake. As such, it lays out the time of the year that this vow is practiced, the goal of this vow, its requirements, and its benefits (see introduction for a discussion of the p vai vow and its literary antecedents in the Tami

vai vow and its literary antecedents in the Tami Ca

Ca kam literary corpus).

kam literary corpus).

These opening verses call out to the gop girls of

girls of  yarp

yarp

i to join in the quest for the pa

i to join in the quest for the pa ai-drum. While pa

ai-drum. While pa ai literally means drum, the

ai literally means drum, the  r

r vai

vai

ava

ava  c

c ryas interpret it variously. It can refer to puru

ryas interpret it variously. It can refer to puru

rtha (the goals of life), kai

rtha (the goals of life), kai karya (loving service), goal, divine grace, favor, and intimacy. Outside of the

karya (loving service), goal, divine grace, favor, and intimacy. Outside of the  r

r vai

vai

ava doctrinal universe, the pa

ava doctrinal universe, the pa ai plays with several registers of meaning including sacred power, sacred time, and of course its Ca

ai plays with several registers of meaning including sacred power, sacred time, and of course its Ca kam association with the king and his all-important drum. I half-translate it as pa

kam association with the king and his all-important drum. I half-translate it as pa ai-drum, foregrounding its literal meaning, while allowing its multiple (theological) meanings to resonate.

ai-drum, foregrounding its literal meaning, while allowing its multiple (theological) meanings to resonate.

In each of the five verses that comprise the p yiram,

yiram,  r

r vai

vai

ava commentators read each of Vi

ava commentators read each of Vi

u’s names mentioned there in and its attendant quality (gu

u’s names mentioned there in and its attendant quality (gu a) as central. In verse 1, he is referred to as N

a) as central. In verse 1, he is referred to as N r

r ya

ya a

a , in verse 2 as Parama

, in verse 2 as Parama , in verse 3 as Uttama

, in verse 3 as Uttama , in verse 4 as Padman

, in verse 4 as Padman bha

bha and finally in verse 5 as D

and finally in verse 5 as D modara

modara .

.

The first song of the Tirupp vai establishes the locale: it transports the audience to

vai establishes the locale: it transports the audience to  yarp

yarp

i (Sanskrit: Gokula) the mythical world of K

i (Sanskrit: Gokula) the mythical world of K

a. Though the transparent poetics of bhakti (discussed by Norman Cutler in Songs of Experience) allow one to insert

a. Though the transparent poetics of bhakti (discussed by Norman Cutler in Songs of Experience) allow one to insert

into the poem, specifically as the leader of the retinue of questing girls, it is actually unclear where the poet has positioned herself in the poem. That is, has

into the poem, specifically as the leader of the retinue of questing girls, it is actually unclear where the poet has positioned herself in the poem. That is, has

(as the final verse seems to indicate) imagined a situation where gop

(as the final verse seems to indicate) imagined a situation where gop girls undertook such a quest? Or is she imagining herself as one of the questing girls? Or is she describing a vow that she actually undertook? Yet, despite the poem’s deep ambiguity, oral narratives, hagiographies, and the ritual culture of

girls undertook such a quest? Or is she imagining herself as one of the questing girls? Or is she describing a vow that she actually undertook? Yet, despite the poem’s deep ambiguity, oral narratives, hagiographies, and the ritual culture of

’s temple in

’s temple in  r

r villiputt

villiputt r, understand the Tirupp

r, understand the Tirupp vai to recount and authentically report a real p

vai to recount and authentically report a real p vai vow undertaken by

vai vow undertaken by

in order to win her lord. Still, it would be disingenuous to suggest that commentators beginning with Periyav

in order to win her lord. Still, it would be disingenuous to suggest that commentators beginning with Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai are unaware of the poem’s rhetorical complexity. Periyav

ai are unaware of the poem’s rhetorical complexity. Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai frames the question of voice and the Tirupp

ai frames the question of voice and the Tirupp vai’s authenticity in terms of caste, wondering how a Brahmin girl like

vai’s authenticity in terms of caste, wondering how a Brahmin girl like

(for she was the foster daughter of the Brahmin garland maker, Vi

(for she was the foster daughter of the Brahmin garland maker, Vi

ucitta

ucitta ) could practice a vow meant for cowherds. He answers his self-imposed query—no doubt anticipating his medieval interlocutors—saying that

) could practice a vow meant for cowherds. He answers his self-imposed query—no doubt anticipating his medieval interlocutors—saying that

simply imagined herself as a gop

simply imagined herself as a gop , because her love for K

, because her love for K

a was so profound. According to Pi

a was so profound. According to Pi

ai and the commentators that follow,

ai and the commentators that follow,

’s imagination was so fertile, and her transformation complete, that she began to smell of milk and curds, like “real” cowherds.

’s imagination was so fertile, and her transformation complete, that she began to smell of milk and curds, like “real” cowherds.

M rka

rka i, the first word of the Tirupp

i, the first word of the Tirupp vai, is of great import for it situates the poem not only temporally in the month that falls between December and January in the Tami

vai, is of great import for it situates the poem not only temporally in the month that falls between December and January in the Tami calendar, but also embeds it within its very specific ritual associations. This month, the ninth month of the Tami

calendar, but also embeds it within its very specific ritual associations. This month, the ninth month of the Tami calendar, is considered especially favored by Vi

calendar, is considered especially favored by Vi

u/K

u/K

a, as specified in Bhagavad G

a, as specified in Bhagavad G t

t 10.35 (“I am the great ritual chant,/the meter of sacred song, the most sacred month [M

10.35 (“I am the great ritual chant,/the meter of sacred song, the most sacred month [M rga

rga ir

ir a] in the year, the spring blooming with flowers.”).1 The reason for the particularity of M

a] in the year, the spring blooming with flowers.”).1 The reason for the particularity of M rka

rka i (Tami

i (Tami form for the Sanskrit month M

form for the Sanskrit month M rga

rga ir

ir a) is that it too like Vi

a) is that it too like Vi

u is neither too hot, nor too cold. In conjunction with the ritual weight of M

u is neither too hot, nor too cold. In conjunction with the ritual weight of M rka

rka i, the poem asserts the auspiciousness of the full moon. The evocation of the moon resonates on multiple levels. The gop

i, the poem asserts the auspiciousness of the full moon. The evocation of the moon resonates on multiple levels. The gop s are imagined as having faces bright and beautiful as the full moon. Further, it anticipates the final lines of this opening verse, where K

s are imagined as having faces bright and beautiful as the full moon. Further, it anticipates the final lines of this opening verse, where K

a’s face reconciles duality, being described as both the sun and the moon. As the commentators frequently point out, while Vi

a’s face reconciles duality, being described as both the sun and the moon. As the commentators frequently point out, while Vi

u is like fire to enemies, his love for his devotees is cool as moonlight.

u is like fire to enemies, his love for his devotees is cool as moonlight.

The quest of the Tirupp vai is a communal one and the opening verse stresses this idea. It is not sufficient to approach god individually, but one must do so in the company of like-minded beings. Here the like-minded are the crowd of gop

vai is a communal one and the opening verse stresses this idea. It is not sufficient to approach god individually, but one must do so in the company of like-minded beings. Here the like-minded are the crowd of gop girls, who are exhorted to bathe during the auspicious hours of the brahmamuh

girls, who are exhorted to bathe during the auspicious hours of the brahmamuh rta, which occurs approximately two hours prior to sunrise. The word n

rta, which occurs approximately two hours prior to sunrise. The word n r

r

a (infinitive, to bathe) is used in this verse to signify both a literal bath and a figurative one. Taking their cue from similar usage Ca

a (infinitive, to bathe) is used in this verse to signify both a literal bath and a figurative one. Taking their cue from similar usage Ca kam akam poems, commentators interpret n

kam akam poems, commentators interpret n r

r

a in the poem to mean union, specifically, sexual union, or in theological terms k

a in the poem to mean union, specifically, sexual union, or in theological terms k

nubhavam (the enjoyment of K

nubhavam (the enjoyment of K

a) or k

a) or k

asa

asa

le

le a (union with K

a (union with K

a). Alternately, bathing in the cool waters with the chill of the early dawn still in the air can also be understood as damping the fire of separation that burns these questing gop

a). Alternately, bathing in the cool waters with the chill of the early dawn still in the air can also be understood as damping the fire of separation that burns these questing gop girls. I have translated n

girls. I have translated n r

r

a as bathe to convey both the literal and figurative meanings. The word n

a as bathe to convey both the literal and figurative meanings. The word n r

r

a literally means to play (

a literally means to play ( ta) in the water (n

ta) in the water (n r).

r).

The opening verse of the Tirupp vai constantly juxtaposes images of fire with those of coolness, realized most fully—as mentioned above—in the description of K

vai constantly juxtaposes images of fire with those of coolness, realized most fully—as mentioned above—in the description of K

a as one whose face is both the sun and the moon. The verse relishes other kinds of juxtapositions as well, particularly in its description of K

a as one whose face is both the sun and the moon. The verse relishes other kinds of juxtapositions as well, particularly in its description of K

a’s foster-parents: Nandagopa and Ya

a’s foster-parents: Nandagopa and Ya od

od . Nandagopa is described as the “one with a sharp spear,” while Ya

. Nandagopa is described as the “one with a sharp spear,” while Ya od

od is the lady with matchless eyes. Commentaries understand the above description to allude to the fierce love that protects K

is the lady with matchless eyes. Commentaries understand the above description to allude to the fierce love that protects K

a in Gokula. Nandagopa, terrifying as any Tami

a in Gokula. Nandagopa, terrifying as any Tami warrior, holds enemies at bay with his terrible weapon. But for Ya

warrior, holds enemies at bay with his terrible weapon. But for Ya od

od , her eyes, sharp as spears (in Tami

, her eyes, sharp as spears (in Tami poetry, women’s eyes are often compared to spears), are her defense against all adversity that might touch her son. The commentators note that these eyes are matchless because they gaze continually upon the lovely form of K

poetry, women’s eyes are often compared to spears), are her defense against all adversity that might touch her son. The commentators note that these eyes are matchless because they gaze continually upon the lovely form of K

a.

a.

For the commentators, the penultimate line of this first verse (n r

r ya

ya a

a

namakk

namakk pa

pa ai taruv

ai taruv

: N

: N r

r ya

ya an alone can give us the pa

an alone can give us the pa ai-drum) holds the key to the entire Tirupp

ai-drum) holds the key to the entire Tirupp vai. I briefly sketch below their reasoning. Even on a literal level, the line above encapsulates the reward for the vow (the pa

vai. I briefly sketch below their reasoning. Even on a literal level, the line above encapsulates the reward for the vow (the pa ai-drum) and from whom the girls receive that reward (N

ai-drum) and from whom the girls receive that reward (N r

r ya

ya a). Rather than choose any of the thousand names of Vi

a). Rather than choose any of the thousand names of Vi

u,

u,

begins her poem by addressing the supreme lord (sarve

begins her poem by addressing the supreme lord (sarve vara) as N

vara) as N r

r ya

ya a. N

a. N r

r ya

ya a is both the one who contains all sentient things (n

a is both the one who contains all sentient things (n ra), as well as the refuge (ayana) for all sentient things (n

ra), as well as the refuge (ayana) for all sentient things (n ra). Thus, the name itself distills for the

ra). Thus, the name itself distills for the  r

r vai

vai

ava commentators one of the key ideas of vi

ava commentators one of the key ideas of vi i

i

dvaita philosophy (qualified nondualism). That is, Vi

dvaita philosophy (qualified nondualism). That is, Vi

u

u r

r ya

ya a is both what is desired (pr

a is both what is desired (pr pya) and the means to that desire (pr

pya) and the means to that desire (pr paka). That is, he is both the way (up

paka). That is, he is both the way (up ya) and the goal (upeya). Finally, the commentators note that

ya) and the goal (upeya). Finally, the commentators note that

has placed an emphasis on two very significant words in this line—N

has placed an emphasis on two very significant words in this line—N r

r ya

ya a

a

: (N

: (N r

r ya

ya a alone) and namakk

a alone) and namakk (for us alone), suggesting both the supremacy of Vi

(for us alone), suggesting both the supremacy of Vi

u-N

u-N r

r ya

ya a, and the uniqueness of the devotee who has surrendered to him.

a, and the uniqueness of the devotee who has surrendered to him.

M rka

rka i: The winter month that falls between December 15–January 15.

i: The winter month that falls between December 15–January 15.

yar

yar

i: Land of the cowherds. The place of K

i: Land of the cowherds. The place of K

a’s childhood.

a’s childhood.

Tirupp vai 2 (Vaiyattu V

vai 2 (Vaiyattu V v

v rk

rk

)

)

If the opening verse locates the poem temporally and spatially in the month of M rka

rka i and in the mythical world of

i and in the mythical world of  yarp

yarp

i, the second verse acts as a veritable guide to the actual performance of the vow. The verse alternates between two lists of ritual obligations that index both what the girls must do and what they must avoid to ensure the successful completion of their quest. They must sing Vi

i, the second verse acts as a veritable guide to the actual performance of the vow. The verse alternates between two lists of ritual obligations that index both what the girls must do and what they must avoid to ensure the successful completion of their quest. They must sing Vi

u’s praises; they must abstain from ghee or milk. They must bathe daily, but refrain from adorning themselves in any way. They must not gossip or speak ill of anyone and instead ought to give alms to those in need. The verse ends on a positive note, asserting once again the significance of singing the praises of K

u’s praises; they must abstain from ghee or milk. They must bathe daily, but refrain from adorning themselves in any way. They must not gossip or speak ill of anyone and instead ought to give alms to those in need. The verse ends on a positive note, asserting once again the significance of singing the praises of K

a in a community of devotees. In its final lines encouraging charity, the commentators note that

a in a community of devotees. In its final lines encouraging charity, the commentators note that

draws a distinction between aiyam—understood as generosity to deserving people—and piccai, which is specifically bhik

draws a distinction between aiyam—understood as generosity to deserving people—and piccai, which is specifically bhik a (alms) given to Brahmins and sanny

a (alms) given to Brahmins and sanny sis (renunciants).

sis (renunciants).

Any vow requires renunciation, and the p vai n

vai n

pu is no exception. Periyav

pu is no exception. Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai and others points out that a vow such as this one undertaken to achieve union with K

ai and others points out that a vow such as this one undertaken to achieve union with K

a requires that one renounce (vair

a requires that one renounce (vair gya) worldly objects that intoxicate the senses, in order to obtain the incomparable intoxicant (paramabhogya) that is god. Nevertheless, in verse 27 of the Tirupp

gya) worldly objects that intoxicate the senses, in order to obtain the incomparable intoxicant (paramabhogya) that is god. Nevertheless, in verse 27 of the Tirupp vai these very relinquished objects—milk, ghee, and adornment—are actively sought and understood as integral to achieving K

vai these very relinquished objects—milk, ghee, and adornment—are actively sought and understood as integral to achieving K

a’s grace. The Tirupp

a’s grace. The Tirupp vai plays with the tension between the desires of this world and those associated with eternal union with Vi

vai plays with the tension between the desires of this world and those associated with eternal union with Vi

u. The quest for K

u. The quest for K

a is the quest for a drum, a symbol that is eventually rejected in the final verses of the Tirupp

a is the quest for a drum, a symbol that is eventually rejected in the final verses of the Tirupp vai as a suitable reward. It is also a vow undertaken for the prosperity of the land made manifest in plentiful rain, but also expressed as the desire for eternal service to K

vai as a suitable reward. It is also a vow undertaken for the prosperity of the land made manifest in plentiful rain, but also expressed as the desire for eternal service to K

a.

a.

In Tirupp vai 2, Vi

vai 2, Vi

u is addressed as parama

u is addressed as parama (The Supreme One). If the first verse figured Vi

(The Supreme One). If the first verse figured Vi

u as the transcendent, inaccessible lord in his heaven, Vaiku

u as the transcendent, inaccessible lord in his heaven, Vaiku

ha, this verse places him on the ocean of milk (p

ha, this verse places him on the ocean of milk (p

ka

ka al), where he manifests, according to the commentators, out of his desire to help sentient beings. Vaiku

al), where he manifests, according to the commentators, out of his desire to help sentient beings. Vaiku

ha is far away, while the ocean of milk is somehow closer. As he reclines on his thousand-headed serpent on the ocean of milk, Vi

ha is far away, while the ocean of milk is somehow closer. As he reclines on his thousand-headed serpent on the ocean of milk, Vi

u practices a profound yoga nidra (meditation), contemplating all the ways that he can help those who need him. So, although he is without comparison (parama

u practices a profound yoga nidra (meditation), contemplating all the ways that he can help those who need him. So, although he is without comparison (parama ), he is also accessible and immanent.

), he is also accessible and immanent.

This third verse develops several central themes laid out in the opening two verses. It focuses primarily on the rewards from the observance of the vow. These blessings are manifest in laukika (worldly) things: plentiful rain, unstintingly generous cows, and an abundant harvest. At the center of the observance of the vow is the ritual bath at the break of dawn, and the communal singing of Vi

u’s glories. These glories however are expressed not through reliving his wondrous deeds, but by remembering Vi

u’s glories. These glories however are expressed not through reliving his wondrous deeds, but by remembering Vi

u’s names (uttama

u’s names (uttama p

p r p

r p

i: singing the names (p

i: singing the names (p r) of Uttama

r) of Uttama ). Periyav

). Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai stresses the point that reciting Vi

ai stresses the point that reciting Vi

u’s names is utterly egalitarian, available to one and all, regardless of gender, birth, or caste.

u’s names is utterly egalitarian, available to one and all, regardless of gender, birth, or caste.

The poem begins with an allusion Vi

u’s avat

u’s avat ra as V

ra as V mana, evoked through the use of the adverbial participle

mana, evoked through the use of the adverbial participle

ki (stretching/spanning). This word is echoed later in the poem in the adjective,

ki (stretching/spanning). This word is echoed later in the poem in the adjective,

ku (tall) to describe the copious harvest. Periyav

ku (tall) to describe the copious harvest. Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai’s commentary explicates that the poet chooses to describe the grain as tall to drive home the gop

ai’s commentary explicates that the poet chooses to describe the grain as tall to drive home the gop s’ single-minded devotion to K

s’ single-minded devotion to K

a in his form as V

a in his form as V mana; everywhere they look, they witness his great deeds.

mana; everywhere they look, they witness his great deeds.

In Tirupp vai 3, Vi

vai 3, Vi

u is addressed as uttama

u is addressed as uttama (lit. excellent one). Periyav

(lit. excellent one). Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai and others following his lead explicate the use of this name in the following ways. First, they contextualize who qualifies as an uttama

ai and others following his lead explicate the use of this name in the following ways. First, they contextualize who qualifies as an uttama . Following well-established guidelines in Sanskrit treatises for categorizing men according to their behavior and actions, the commentators identify an uttama

. Following well-established guidelines in Sanskrit treatises for categorizing men according to their behavior and actions, the commentators identify an uttama as one who performs good deeds without expecting a reward. This is unlike an adam

as one who performs good deeds without expecting a reward. This is unlike an adam tma

tma , who does evil things in return for the good that is done to him; or the atama

, who does evil things in return for the good that is done to him; or the atama , who does nothing in return for a service done for him; or the madhyama

, who does nothing in return for a service done for him; or the madhyama , who only does what is required of him in response to any aid he is given. The commentators further assert, even the first level of interpretation—the word gloss—that Vi

, who only does what is required of him in response to any aid he is given. The commentators further assert, even the first level of interpretation—the word gloss—that Vi

u is not just an uttama

u is not just an uttama , but Pur

, but Pur usottama

usottama (Supreme/most excellent among men).

(Supreme/most excellent among men).

kayal: A carp fish, Cyprinus fimbriatus.

kuva ai: Indian purple water lily.

ai: Indian purple water lily.

Tirupp vai 4 is exemplary of

vai 4 is exemplary of

’s dexterity as a poet. It focuses on an extended simile that compares the gathering rain (god of rain) to the body of god. Usually, as in verse 1 of the Tirupp

’s dexterity as a poet. It focuses on an extended simile that compares the gathering rain (god of rain) to the body of god. Usually, as in verse 1 of the Tirupp vai, Vi

vai, Vi

u’s body is compared to the dark rain clouds, but here that comparison is reversed. Both logic and poetic theory demand that a known object (upam

u’s body is compared to the dark rain clouds, but here that comparison is reversed. Both logic and poetic theory demand that a known object (upam na) is employed to describe an unknown entity (upameya). Therefore god (Vi

na) is employed to describe an unknown entity (upameya). Therefore god (Vi

u/K

u/K

a) who is indescribable and unknowable is usually described as dark as the rain clouds. In this verse,

a) who is indescribable and unknowable is usually described as dark as the rain clouds. In this verse,

reverses this correspondence, such that K

reverses this correspondence, such that K

a is the upam

a is the upam na and the landscape (here, the rain clouds) is the object to be described (upameya). Tirupp

na and the landscape (here, the rain clouds) is the object to be described (upameya). Tirupp vai 4 is not the only instance of

vai 4 is not the only instance of

’s use of this particular rhetorical technique; it occurs frequently in the N

’s use of this particular rhetorical technique; it occurs frequently in the N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i, most notably in that poem’s tenth decad, where various plants, flowers, and birds are chastised for assuming the form of the heroine’s divine lover.

i, most notably in that poem’s tenth decad, where various plants, flowers, and birds are chastised for assuming the form of the heroine’s divine lover.

This verse begins with a vocative, where the lord of rain is addressed with the endearment ka

. Because, ka

. Because, ka

is also the Tami

is also the Tami version of K

version of K

a, commentators interpret the line to indicate that for the gop

a, commentators interpret the line to indicate that for the gop s god is everywhere. Ultimately, then this is no simple simile; the landscape is not just a suggestion of embodiment, but is itself the embodiment of divinity. Paradoxically, the speaker(s) of the poem also scold the clouds for trying to imitate god. The commentators elaborate the above point as follows: while the clouds can turn dark like K

s god is everywhere. Ultimately, then this is no simple simile; the landscape is not just a suggestion of embodiment, but is itself the embodiment of divinity. Paradoxically, the speaker(s) of the poem also scold the clouds for trying to imitate god. The commentators elaborate the above point as follows: while the clouds can turn dark like K

a, and the sky can thunder like his conch, and lightning can flash like his cakra, the rain can never be full of love like god. To illustrate the point of Vi

a, and the sky can thunder like his conch, and lightning can flash like his cakra, the rain can never be full of love like god. To illustrate the point of Vi

u’s unwavering love when one takes refuge in him, Periyav

u’s unwavering love when one takes refuge in him, Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai draws a lovely comparison. Unlike the plants that look to the sky, dependent on rain for their nourishment, a devotee who has taken refuge in him is like the field through which a river runs, unbidden.

ai draws a lovely comparison. Unlike the plants that look to the sky, dependent on rain for their nourishment, a devotee who has taken refuge in him is like the field through which a river runs, unbidden.

In this verse Vi

u is described as

u is described as

i mutalva

i mutalva padman

padman bha

bha (Padman

(Padman bha who is the cause/first of all time). The word mutal means both cause and first. The commentators gloss the phrase as the lord who is the eternal cause of all things, parsing

bha who is the cause/first of all time). The word mutal means both cause and first. The commentators gloss the phrase as the lord who is the eternal cause of all things, parsing

(lit. a very long time; the final deluge, final destruction) as the one who exists eternally. As the commentators note, describing Vi

(lit. a very long time; the final deluge, final destruction) as the one who exists eternally. As the commentators note, describing Vi

u as Padman

u as Padman bha and as the primordial cause of the world is particularly effective. He is the cause of time (

bha and as the primordial cause of the world is particularly effective. He is the cause of time (

i) and stands beyond time as the primordial one. He is the cause (mutal) of the final destruction, but as the foremost divinity (mutal) is also the one who protects the world in his belly in the final deluge. And then, through Brahm

i) and stands beyond time as the primordial one. He is the cause (mutal) of the final destruction, but as the foremost divinity (mutal) is also the one who protects the world in his belly in the final deluge. And then, through Brahm , who rises from the lotus that emerges from his belly, he creates that world once again.

, who rises from the lotus that emerges from his belly, he creates that world once again.

Commentators argue that the sv pade

pade

rtha (esoteric meaning) equates the rain clouds to the great teachers of the

rtha (esoteric meaning) equates the rain clouds to the great teachers of the  r

r vai

vai

ava lineage. In this interpretation, the rain/rain clouds are the teacher’s (

ava lineage. In this interpretation, the rain/rain clouds are the teacher’s ( c

c rya) compassion (day

rya) compassion (day ) and knowledge (jñ

) and knowledge (jñ na), which guide the devotee to Vi

na), which guide the devotee to Vi

u.

u.

valampuri: lit. right turning. The name of Vi

u’s conch.

u’s conch.

r

r ga: the name of Vi

ga: the name of Vi

u’s bow.

u’s bow.

This is the final verse of the p yiram and like Tirupp

yiram and like Tirupp vai 3 and 4, describes the benefits of undertaking the p

vai 3 and 4, describes the benefits of undertaking the p vai vow. It also represents a turn away from the worldly rewards that the gop

vai vow. It also represents a turn away from the worldly rewards that the gop s requested in the previous two verses. Instead, K

s requested in the previous two verses. Instead, K

a is enjoined to burn away all of the gop

a is enjoined to burn away all of the gop s’ past misdeeds and in a sense prepare them for eternal service to him.

s’ past misdeeds and in a sense prepare them for eternal service to him.

Much of the commentary for this verse focuses on the word t ya, “pure,” which

ya, “pure,” which

uses to describe the Yamun

uses to describe the Yamun , the gop

, the gop girls, and the flowers that they bring to K

girls, and the flowers that they bring to K

a as an offering. According to the commentators, the Yamun

a as an offering. According to the commentators, the Yamun attains its purity for several reasons. First, she parted of her own volition on the night of K

attains its purity for several reasons. First, she parted of her own volition on the night of K

a’s birth, so that Vasudeva might cross her and spirit the child K

a’s birth, so that Vasudeva might cross her and spirit the child K

a to safety. Second, she had the unique privilege of touching and being touched by K

a to safety. Second, she had the unique privilege of touching and being touched by K

a, because he bathed and played in her waters during his childhood in Gokula. To further stress the unrivaled purity of the Yamun

a, because he bathed and played in her waters during his childhood in Gokula. To further stress the unrivaled purity of the Yamun , the commentators offer a contrast, with an explication of an episode taken from the R

, the commentators offer a contrast, with an explication of an episode taken from the R m

m ya

ya a. Here, they allude to an episode in R

a. Here, they allude to an episode in R m

m ya

ya a where S

a where S t

t , abducted by R

, abducted by R va

va a, beseeched the river God

a, beseeched the river God var

var to report it to R

to report it to R ma. The river, fearing R

ma. The river, fearing R va

va a’s wrath, failed to do so. The Yamun

a’s wrath, failed to do so. The Yamun , on the other hand, was fearless of Ka

, on the other hand, was fearless of Ka sa’s wrath, though she flowed right beside his dominion and aided Vasudeva and saw K

sa’s wrath, though she flowed right beside his dominion and aided Vasudeva and saw K

a to safety.

a to safety.

The commentators begin a meditation on “purity” in order to explain how the gop girls claim such a state, especially when they have yet to bathe. Their rhetorical question asserts that the purity referred to here is not ritual purity, but the purity of intent and love for god. To drive home the point, the commentators offer several paradigmatic examples. In the R

girls claim such a state, especially when they have yet to bathe. Their rhetorical question asserts that the purity referred to here is not ritual purity, but the purity of intent and love for god. To drive home the point, the commentators offer several paradigmatic examples. In the R m

m ya

ya a, R

a, R va

va a’s brother Vibh

a’s brother Vibh

a

a a’s did not bathe before surrendering (

a’s did not bathe before surrendering ( ara

ara

gati) to R

gati) to R ma. In the Mah

ma. In the Mah bh

bh rata, K

rata, K

a’s great friend and disciple Arjuna did not bathe before he heard the Bhagavad G

a’s great friend and disciple Arjuna did not bathe before he heard the Bhagavad G t

t from K

from K

a. And finally Draupad

a. And finally Draupad , the Mah

, the Mah bh

bh rata’s heroine, sought K

rata’s heroine, sought K

a’s aid when she was menstruating.

a’s aid when she was menstruating.

The commentators elucidate that

describes the flowers as pure (t

describes the flowers as pure (t malar) because their final destination is K

malar) because their final destination is K

a’s feet. Just as the Yamun

a’s feet. Just as the Yamun attained her purity through association with K

attained her purity through association with K

a’s divine body, and just as the gop

a’s divine body, and just as the gop girls are purified by their abiding love for K

girls are purified by their abiding love for K

a, so too are ordinary flowers transformed by the intent of their worshippers and their use in the service of K

a, so too are ordinary flowers transformed by the intent of their worshippers and their use in the service of K

a.

a.

In this verse, K

a is addressed as D

a is addressed as D modara (the one who bears the [scar] left by the rope). The name refers to an episode from the childhood days of K

modara (the one who bears the [scar] left by the rope). The name refers to an episode from the childhood days of K

a, when his foster-mother Ya

a, when his foster-mother Ya od

od bound him to a grinding stone with a rope (D

bound him to a grinding stone with a rope (D ma) as a punishment. This name, perhaps above all, serves as an eternal reminder of K

ma) as a punishment. This name, perhaps above all, serves as an eternal reminder of K

a’s love for his devotees, and the commentators understand it to encapsulate Vi

a’s love for his devotees, and the commentators understand it to encapsulate Vi

u’s attribute as

u’s attribute as

rita paratantra (devotion to his devotees).

rita paratantra (devotion to his devotees).

M ya

ya : lord of mystery, cunning one. A name of K

: lord of mystery, cunning one. A name of K

a.

a.

Mathur of the North: the city of K

of the North: the city of K

a’s birth.

a’s birth.

refers to it as such to distinguish it from the southern city of Maturai.

refers to it as such to distinguish it from the southern city of Maturai.

Tirupp vai 6–15: General Introduction

vai 6–15: General Introduction

The next ten verses comprise the tuyile ai (waking-up) section of the Tirupp

ai (waking-up) section of the Tirupp vai. In each verse the gop

vai. In each verse the gop girls rouse a friend and encourage her to join their quest. This rhetorical strategy is successful in asserting the inherent superiority of a communal devotion to god. The community of questing girls embodies the principle of loving god in the company of good, like-minded people. Though each of the awakened girls is eventually absorbed into the ubiquitous group, each of them in their role as the sleeping girl retains a distinctive personality, most clearly in evidence in the fifteenth verse that closes the section.

girls rouse a friend and encourage her to join their quest. This rhetorical strategy is successful in asserting the inherent superiority of a communal devotion to god. The community of questing girls embodies the principle of loving god in the company of good, like-minded people. Though each of the awakened girls is eventually absorbed into the ubiquitous group, each of them in their role as the sleeping girl retains a distinctive personality, most clearly in evidence in the fifteenth verse that closes the section.

These ten verses also signal the beginning of the journey into the interior that reaches its fruition between verses 16–20 of the Tirupp vai. The girls call out to their friends poised on the threshold of their homes; they never actually enter their houses, but stand on the porch, the threshold or the doorway. This reticence to engage spatially the inner space of the devotee suggests that it is a privilege reserved for the private, but joint, enjoyment of K

vai. The girls call out to their friends poised on the threshold of their homes; they never actually enter their houses, but stand on the porch, the threshold or the doorway. This reticence to engage spatially the inner space of the devotee suggests that it is a privilege reserved for the private, but joint, enjoyment of K

a in his home.

a in his home.

In an anachronistic reading, Vanamamalai Jiyar and other later  r

r vai

vai

ava commentators have argued that each of these ten verses alludes to the awakening of one of the other eleven

ava commentators have argued that each of these ten verses alludes to the awakening of one of the other eleven

v

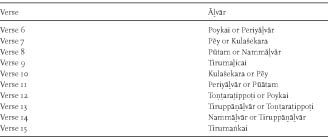

v r. The correspondences are as indicated in table 2:2

r. The correspondences are as indicated in table 2:2

TABLE 2. Tirupp vai Verse and

vai Verse and

v

v r Concordance

r Concordance

There is an additional tradition that associates each of these verses with one of the ten  c

c ryas in the order listed in the

ryas in the order listed in the  r

r vai

vai

avas’

avas’  c

c rya parampar

rya parampar (lineage of teachers).

(lineage of teachers).

The commentaries for many of these next ten verses are interspersed with lively and imagined dialogue between the gop girls and the sleeping friends, though only one verse (verse 15) in the Tirupp

girls and the sleeping friends, though only one verse (verse 15) in the Tirupp vai takes that form. In the notes below, I have replicated the dialogic format only for the opening phrase of Tirupp

vai takes that form. In the notes below, I have replicated the dialogic format only for the opening phrase of Tirupp vai 6 in order to give a sense of the commentaries’ form. It must be noted that this kind of imagined dialogue is a regular feature of

vai 6 in order to give a sense of the commentaries’ form. It must be noted that this kind of imagined dialogue is a regular feature of  r

r vai

vai

ava commentary. Sometimes the dialogue is introduced to provide context for a particular theological exposition. In other cases, it is interjected in response to a silent question asked by an imaginary audience, and occasionally, the commentator provides both the question and the answer.

ava commentary. Sometimes the dialogue is introduced to provide context for a particular theological exposition. In other cases, it is interjected in response to a silent question asked by an imaginary audience, and occasionally, the commentator provides both the question and the answer.

The verse inaugurating the second section of the Tirupp vai aptly begins with the chirping of birds to signal the dawn and the subsequent arrival of the dawn. The urgency of the moment is conveyed through the addition of the particle pu

vai aptly begins with the chirping of birds to signal the dawn and the subsequent arrival of the dawn. The urgency of the moment is conveyed through the addition of the particle pu

(um)—even the birds are awake. But when the girl who was already supposed to be awake remains slumbering and refuses to acknowledge the signs of dawn, the group of girls roundly scold her thus:

(um)—even the birds are awake. But when the girl who was already supposed to be awake remains slumbering and refuses to acknowledge the signs of dawn, the group of girls roundly scold her thus:

“Were you not supposed to be awake at the crack of dawn? Why are you

still asleep?”

“O, but it is not dawn as yet.”

“No, it is already morning.”

“So, what is the proof that it has in fact dawned? I can’t accept that it is morning simply because you say it is so.”

“Isn’t it enough that we have experienced it?”

“The rest of you just don’t sleep. So, how do know it is dawn?”

It is to this final question that the girls answer:

“Listen, even the birds are chirping.”

The dialogue continues in much the same vein as the gop girls try various arguments to cajole their reluctant friend out of bed. They allude to K

girls try various arguments to cajole their reluctant friend out of bed. They allude to K

a suckling at the breast of the demoness P

a suckling at the breast of the demoness P tan

tan , in the hope that fear for the safety of the child will hasten the girl out of sleep. Next, they gesture to the exemplary muni and yogi (translated as sages and ascetics) who always hold Vi

, in the hope that fear for the safety of the child will hasten the girl out of sleep. Next, they gesture to the exemplary muni and yogi (translated as sages and ascetics) who always hold Vi

u in their hearts. Here the commentaries take note of the fact that the poet appears to make a distinction between muni (sages) and yogi (ascetics), a distinction which is similar to the different kinds of charity and philanthropy (aiyam, piccai) that

u in their hearts. Here the commentaries take note of the fact that the poet appears to make a distinction between muni (sages) and yogi (ascetics), a distinction which is similar to the different kinds of charity and philanthropy (aiyam, piccai) that

alludes to in Tirupp

alludes to in Tirupp vai 2. In this case, the commentators explain that the former (muni) are those who continuously contemplate Vi

vai 2. In this case, the commentators explain that the former (muni) are those who continuously contemplate Vi

u, while the latter are those, like R

u, while the latter are those, like R ma’s brother Lak

ma’s brother Lak ma

ma a, whose austerity (yog

a, whose austerity (yog bhy

bhy sa) is to be in god’s eternal service. The implication of the commentators’ interpretative move is that the girls who remain asleep are the muni, and those who hasten to awaken them in order that they too may join the quest are like the yogi. While both kinds of spiritual activity are valued and necessary, the commentators subtly suggest that loving service (kai

sa) is to be in god’s eternal service. The implication of the commentators’ interpretative move is that the girls who remain asleep are the muni, and those who hasten to awaken them in order that they too may join the quest are like the yogi. While both kinds of spiritual activity are valued and necessary, the commentators subtly suggest that loving service (kai karya) such as that of the exemplary Lak

karya) such as that of the exemplary Lak ma

ma a is preferable.

a is preferable.

Finally, when all these arguments fail to rouse the girl, her friends gathered together outside her door remind her that the “great sound Hari” (p raravam) reverberates through the morning air, beckoning devotees toward contemplation. The phrase p

raravam) reverberates through the morning air, beckoning devotees toward contemplation. The phrase p raravam (great sound) is used to describe both the sound of the conch and the sound of the name of god. Given the Tirupp

raravam (great sound) is used to describe both the sound of the conch and the sound of the name of god. Given the Tirupp vai’s emphasis on the recitation of god’s names, it is no surprise that the first verse in the poem’s second section evokes this central rite of Vi

vai’s emphasis on the recitation of god’s names, it is no surprise that the first verse in the poem’s second section evokes this central rite of Vi

u worship.

u worship.

Garu a: the divine eagle, Vi

a: the divine eagle, Vi

u’s vehicle.

u’s vehicle.

aka

aka a: the demon who assumed the form of a cart.

a: the demon who assumed the form of a cart.

For the commentators, the theological implication of this verse is located in the figure of the still-sleeping girl, who is described in contradictory terms. In the verse’s opening lines, her friends call out to her as “p y pe

y pe

,” which literally means “ghost (p

,” which literally means “ghost (p y) girl.” As the verse reaches it conclusion, these same friends address her as n

y) girl.” As the verse reaches it conclusion, these same friends address her as n yaka pe

yaka pe pi

pi

y, literally, “the girl who is the leader.” The word p

y, literally, “the girl who is the leader.” The word p y has connotations of possession, and according to traditional interpretations, indicates that the girl has been taken over by K

y has connotations of possession, and according to traditional interpretations, indicates that the girl has been taken over by K

a and has lost all associations with this world. Yet, there is also a keen sense that the girl is still sleeping and haunts the realm of dreams. It is for this reason that I have chosen to translate the phrase as “witless girl ghost of a girl” to connote the insensate state of sleeping as well as possession.

a and has lost all associations with this world. Yet, there is also a keen sense that the girl is still sleeping and haunts the realm of dreams. It is for this reason that I have chosen to translate the phrase as “witless girl ghost of a girl” to connote the insensate state of sleeping as well as possession.

According to Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai and other commentators, the latter phrase n

ai and other commentators, the latter phrase n yaka pe

yaka pe pi

pi

y suggests that the girl is well versed in mystical knowledge. The juxtaposition of these two diametrically opposed descriptives implies that it is unbecoming of a girl who has experienced K

y suggests that the girl is well versed in mystical knowledge. The juxtaposition of these two diametrically opposed descriptives implies that it is unbecoming of a girl who has experienced K

a (vi

a (vi

u-N

u-N r

r ya

ya a) to continue to sleep. This is a line of reasoning that the retinue of gop

a) to continue to sleep. This is a line of reasoning that the retinue of gop girls continually employ in the “waking-up-the-girls” section of the Tirupp

girls continually employ in the “waking-up-the-girls” section of the Tirupp vai. We can also interpret the mild insult dealt to the sleeping girl to argue for the primacy of loving god with a community of devotees as opposed to individually. This certainly is in keeping with the general theme of the Tirupp

vai. We can also interpret the mild insult dealt to the sleeping girl to argue for the primacy of loving god with a community of devotees as opposed to individually. This certainly is in keeping with the general theme of the Tirupp vai.

vai.

In the Tirupp vai, K

vai, K

a is often identified or collapsed with Vi

a is often identified or collapsed with Vi

uN

uN r

r ya

ya a; in this verse, K

a; in this verse, K

a is referred to as m

a is referred to as m rti (embodiment) or avat

rti (embodiment) or avat ra of Vi

ra of Vi

u. The phrase - n

u. The phrase - n r

r ya

ya a

a m

m rti is interpreted in the commentaries to indicate both Vi

rti is interpreted in the commentaries to indicate both Vi

u’s embodiment as K

u’s embodiment as K

a and his form as the god who dwells in all sentient things (antary

a and his form as the god who dwells in all sentient things (antary min). The feats of K

min). The feats of K

a alluded to in the above verse are understood to signify specific attributes of god. In his defeat of the demon Ke

a alluded to in the above verse are understood to signify specific attributes of god. In his defeat of the demon Ke i, K

i, K

a demonstrates unhesitating and maternal protection (v

a demonstrates unhesitating and maternal protection (v tsalya) for his devotees; in his descent as K

tsalya) for his devotees; in his descent as K

a, he demonstrates his limitless compassion, as well as his immaculate nature (sau

a, he demonstrates his limitless compassion, as well as his immaculate nature (sau

lya).

lya).

aicc

aicc tta

tta : King crow.

: King crow.

Each verse in this section of the Tirupp vai can be read as marking the gradual progression of the dawn. In the previous verse, one can imagine that the sky is still dark and the still, crisp early-morning air is broken by the piercing calls of birds. This verse opens with the beginnings of first light. A line of light on the horizon breaks the darkness of the sky; the buffaloes have begun to stir. The buffaloes have been let out to graze for a short time in a contained area (ci

vai can be read as marking the gradual progression of the dawn. In the previous verse, one can imagine that the sky is still dark and the still, crisp early-morning air is broken by the piercing calls of birds. This verse opens with the beginnings of first light. A line of light on the horizon breaks the darkness of the sky; the buffaloes have begun to stir. The buffaloes have been let out to graze for a short time in a contained area (ci u v

u v

u), prior to being allowed to roam freely late in the day, a practice common among cowherds. Periyav

u), prior to being allowed to roam freely late in the day, a practice common among cowherds. Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai suggests that

ai suggests that

’s use of this detail is evidence of her complete identification with the cowherding community, contrary to her status as a Brahmin girl. In exegetical moments such as these the ambiguity of the speaker of the poem and the poet comes to the fore. The commentators not only insert

’s use of this detail is evidence of her complete identification with the cowherding community, contrary to her status as a Brahmin girl. In exegetical moments such as these the ambiguity of the speaker of the poem and the poet comes to the fore. The commentators not only insert

into the poem, but also collapse the plural voices of the gop

into the poem, but also collapse the plural voices of the gop girls to

girls to

’s singular voice. In a sense—and paradoxically so—a poem that exalts communal worship becomes reflective of a particular and individual experience.

’s singular voice. In a sense—and paradoxically so—a poem that exalts communal worship becomes reflective of a particular and individual experience.

Tirupp vai 8 builds on the significance of approaching K

vai 8 builds on the significance of approaching K

a accompanied by fellow devotees. The girls insist that they wait for their still-sleeping friend, demonstrating the importance of communal devotion toward Vi

a accompanied by fellow devotees. The girls insist that they wait for their still-sleeping friend, demonstrating the importance of communal devotion toward Vi

u. The act of going to god is itself understood as consequential. To illustrate this point, the commentators offer a reference to Akr

u. The act of going to god is itself understood as consequential. To illustrate this point, the commentators offer a reference to Akr ra, one of K

ra, one of K

a’s devotees, who was sent as a messenger to K

a’s devotees, who was sent as a messenger to K

a by the evil Ka

a by the evil Ka sa. The significance of this allusion is that Akr

sa. The significance of this allusion is that Akr ra’s devotion, and the very act of journeying toward K

ra’s devotion, and the very act of journeying toward K

a, even if on a nefarious mission, is sufficient to elicit Vi

a, even if on a nefarious mission, is sufficient to elicit Vi

u’s grace.

u’s grace.

The gop s’ single-minded goal of going to K

s’ single-minded goal of going to K

a implies that they are not content to wait passively for their beloved to return to them; rather, they have seized the initiative to make him accept them. Periyav

a implies that they are not content to wait passively for their beloved to return to them; rather, they have seized the initiative to make him accept them. Periyav cc

cc

Pi

Pi

ai interprets this act of going (ce

ai interprets this act of going (ce

u) to K

u) to K

a to emphasize the intimacy of the bond between god and devotee. He says that the girls go to K

a to emphasize the intimacy of the bond between god and devotee. He says that the girls go to K

a to display their bodies grown emaciated from their separation from him. Up until this point, each girl has experienced K

a to display their bodies grown emaciated from their separation from him. Up until this point, each girl has experienced K

a internally, individually, and in secret. This is suggested by how the girls have been addressed thus far: n

a internally, individually, and in secret. This is suggested by how the girls have been addressed thus far: n yaka pe

yaka pe pi

pi

y (leader among the girls), k

y (leader among the girls), k tukalam u

tukalam u aiya p

aiya p v

v y (joyous girl), p

y (joyous girl), p y pe

y pe (witless ghost of a girl). Now, the opportunity, under the pretext of the p

(witless ghost of a girl). Now, the opportunity, under the pretext of the p vai vow, to experience K

vai vow, to experience K

a publicly, with no secrecy, and in the company of fellow devotees presents itself and each girl is urged not to squander it.

a publicly, with no secrecy, and in the company of fellow devotees presents itself and each girl is urged not to squander it.

The sleeping girl (p v

v y) in Tirupp

y) in Tirupp vai 8 is described as joyous (k

vai 8 is described as joyous (k tukalam u

tukalam u aiya), which the commentators attribute to her having already experienced and enjoyed K

aiya), which the commentators attribute to her having already experienced and enjoyed K

a. But this in itself is not sufficient in their minds to merit such an extravagant description. They opine that she is joyous because she is dear to K

a. But this in itself is not sufficient in their minds to merit such an extravagant description. They opine that she is joyous because she is dear to K

a. Alternately, the word p

a. Alternately, the word p v

v y is interpreted as encapsulating a rhetorical question: will you also be like the great lord who does not understand the suffering of women?

y is interpreted as encapsulating a rhetorical question: will you also be like the great lord who does not understand the suffering of women?

In the concluding phala  ruti verses of the Tirupp

ruti verses of the Tirupp vai and N

vai and N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i,

i,

constantly stresses the wealth and prosperity of Putuvai (lit. New Town, identified with contemporary

constantly stresses the wealth and prosperity of Putuvai (lit. New Town, identified with contemporary  r

r villiputt

villiputt r), a city crowded with resplendent, towering mansions, beautiful women, and perfect priests. Some of the grandeur of

r), a city crowded with resplendent, towering mansions, beautiful women, and perfect priests. Some of the grandeur of

’s Putuvai infiltrates her dense description of the slumbering maiden’s home. The sleeping girl’s mansion is studded with gems that the commentaries assert are naturally pure and without blemish: for them it is a mansion fashioned after

’s Putuvai infiltrates her dense description of the slumbering maiden’s home. The sleeping girl’s mansion is studded with gems that the commentaries assert are naturally pure and without blemish: for them it is a mansion fashioned after

’s own home in

’s own home in  r

r villiputt

villiputt r. The brilliant gems so refract the light of the single lamp inside her home that it seems to the girls standing outside that her home is filled with lights. It is in such a spectacular setting that the girl continues to sleep despite her companions’ entreaties. Her bed is so luxurious that it coaxes even one who has no wish for rest into a deep slumber. The girls are nevertheless baffled: after all, how can one continue to sleep, when the anguish of separation from K

r. The brilliant gems so refract the light of the single lamp inside her home that it seems to the girls standing outside that her home is filled with lights. It is in such a spectacular setting that the girl continues to sleep despite her companions’ entreaties. Her bed is so luxurious that it coaxes even one who has no wish for rest into a deep slumber. The girls are nevertheless baffled: after all, how can one continue to sleep, when the anguish of separation from K

a makes it seem a bed of fire or of thorns? Simply put, sleep is antithetical to the experience of love, especially when separated from one’s beloved. Therefore, how can this girl continue to sleep? The above is the context commentators provide for the question the gop

a makes it seem a bed of fire or of thorns? Simply put, sleep is antithetical to the experience of love, especially when separated from one’s beloved. Therefore, how can this girl continue to sleep? The above is the context commentators provide for the question the gop s address to the girl’s mother:

s address to the girl’s mother:

“Is she mute that she cannot answer our summons? Even if she cannot

respond, can she not hear us calling? Or is she bewitched by the

enchanting name of K

a?”

a?”

N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i 2.1, spoken in the voice of young gop

i 2.1, spoken in the voice of young gop s building sandcastles, expresses and expands on a similar notion. The young girls tormented by a mischievous K

s building sandcastles, expresses and expands on a similar notion. The young girls tormented by a mischievous K

a who insists on kicking down their fragile sandcastles say:

a who insists on kicking down their fragile sandcastles say:

O N r

r ya

ya a! Praised with a thousand names!

a! Praised with a thousand names!

O Nara! Raised as Ya od

od ’s son!

’s son!

We are unable to escape the troubles

you inflict upon us.

In N cciy

cciy r Tirumo

r Tirumo i 2.4, these same girls insist that they are entranced by K

i 2.4, these same girls insist that they are entranced by K

a despite themselves, and despite his many torments:

a despite themselves, and despite his many torments:

Lord, dark as the rain clouds

your charming words hold us in a thrall,

your endearing ways captivate us

your face bewitches us like an incantation.

In Tirupp vai 9, K

vai 9, K

a is addressed by three names: M

a is addressed by three names: M m

m ya

ya , M

, M dhava

dhava , and Vaiku

, and Vaiku

ha

ha , which are interpreted in the commentarial traditions as reflecting Vi

, which are interpreted in the commentarial traditions as reflecting Vi

u’s essential qualities (gu

u’s essential qualities (gu as). M

as). M m

m ya

ya (lit. Great Mysterious One) signifies the lord’s saulabhya (accessibility), for he deigned to descend to earth, mingle with his devotees, and astonish them with his wondrous feats. The name Vaiku

(lit. Great Mysterious One) signifies the lord’s saulabhya (accessibility), for he deigned to descend to earth, mingle with his devotees, and astonish them with his wondrous feats. The name Vaiku

ha

ha (lit. Lord of Vaiku

(lit. Lord of Vaiku

ha) indicates his paratva (transcendence), for this supreme lord (paradevata/jagatsv

ha) indicates his paratva (transcendence), for this supreme lord (paradevata/jagatsv min) is the one who resides in Vaiku

min) is the one who resides in Vaiku

ha surrounded by the nityas

ha surrounded by the nityas ris (eternal beings), bhaktas (devotees), and bh

ris (eternal beings), bhaktas (devotees), and bh gavatas (those who worship Vi

gavatas (those who worship Vi

u). M

u). M dhava

dhava is interpreted to indicate his inseparability from Lak

is interpreted to indicate his inseparability from Lak m

m (M

(M ), who as S

), who as S t

t , R

, R ma’s wife in the R

ma’s wife in the R m

m ya

ya a, was compassionate even to the r

a, was compassionate even to the r k

k asas that enforced her imprisonment in La

asas that enforced her imprisonment in La ka and tormented her for sport.

ka and tormented her for sport.

Tirupp vai 9 also ends with a call to the slumbering girl to join the questing group of gop

vai 9 also ends with a call to the slumbering girl to join the questing group of gop s in singing the many names of Vi

s in singing the many names of Vi

u.

u.

M mi: lit. Aunt.

mi: lit. Aunt.