USING A MOBILE DEVICE IN EUROPE

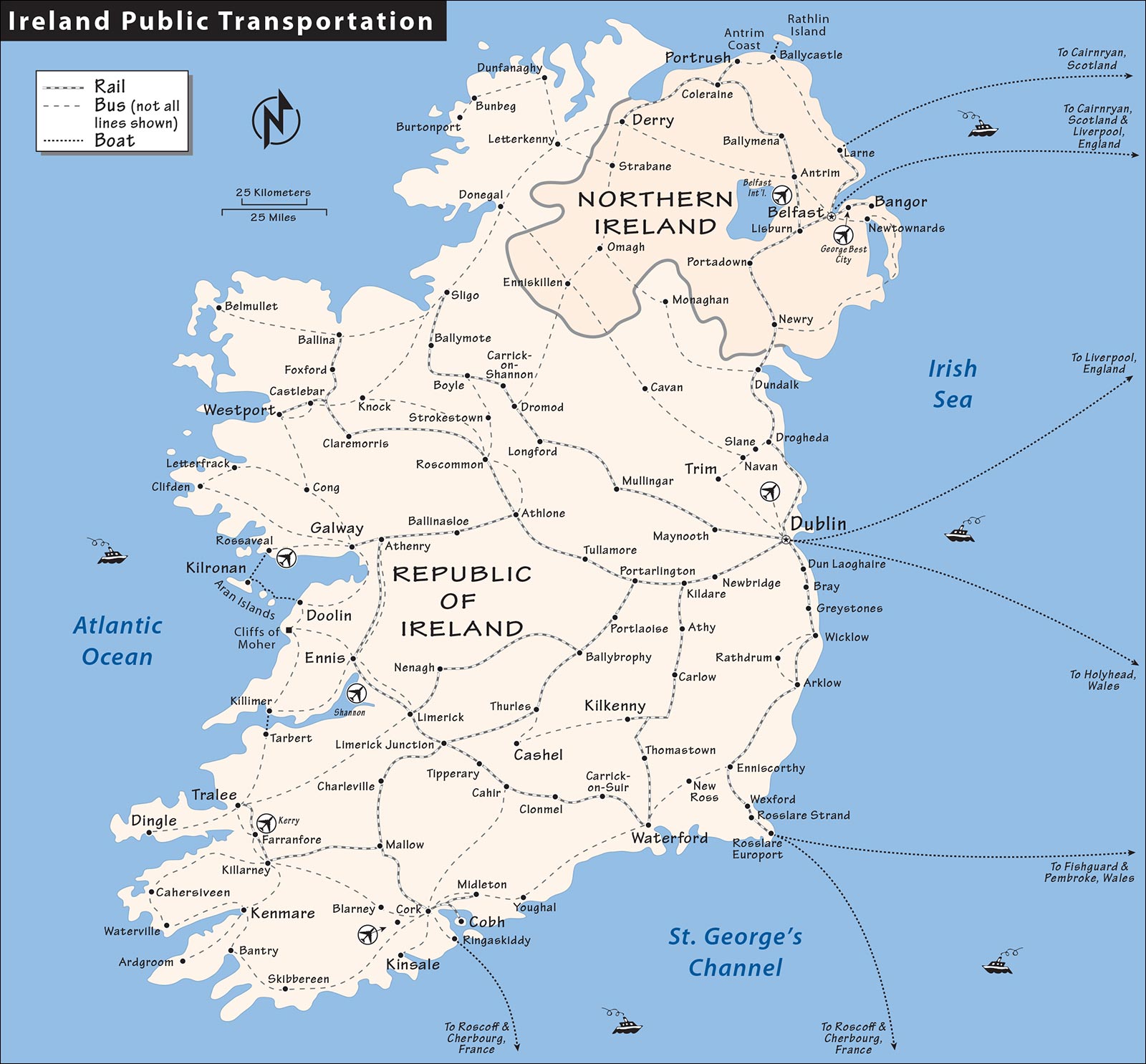

Map: Ireland Public Transportation

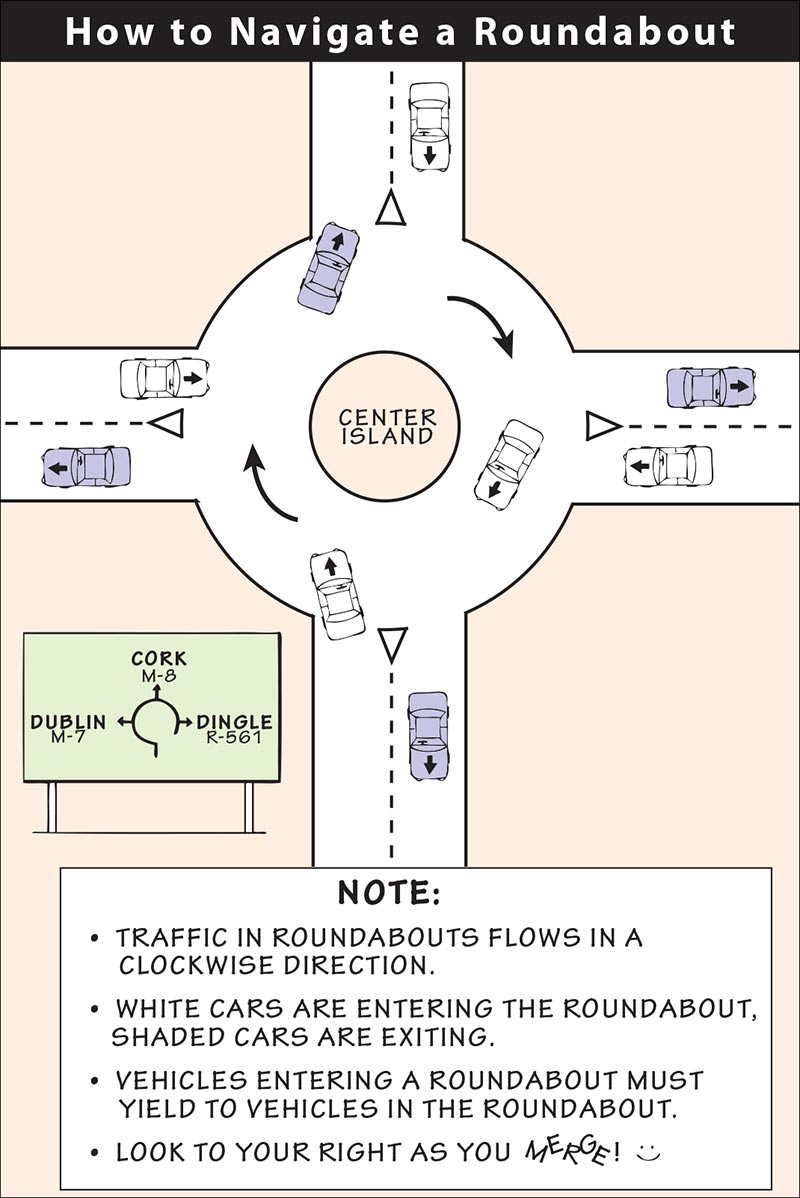

Map: How to Navigate a Roundabout

This chapter covers the practical skills of European travel: how to get tourist information, pay for things, sightsee efficiently, find good-value accommodations, eat affordably but well, use technology wisely, and get between destinations smoothly. To round out your knowledge, check out “Resources from Rick Steves.” For more information on these topics, see www.ricksteves.com/travel-tips.

Ireland’s two government-funded tourist offices (one for the Republic and one for the North) offer a wealth of information. Before your trip, scan their websites. For the Republic of Ireland, visit www.discoverireland.ie. For Northern Ireland, use www.discovernorthernireland.com. At either site, you can download brochures, maps, ask questions, and request that information be mailed to you (such as a free vacation-planning packet, regional and city maps, walking routes, and festival schedules).

In Ireland, a good first stop in any town is generally the tourist information office (abbreviated TI in this book). Avoid ad agencies masquerading as TIs, especially in Dublin—use the official TI. Fáilte Ireland TIs are information dispensaries with trained staff that don’t sell anything or take commissions. I make a point to swing by the local TI to confirm sightseeing plans, pick up a city map, and get information on public transit, walking tours, special events, and nightlife. Prepare a list of questions and a proposed plan to double-check. Many TIs have information on the entire country or at least the region, so try to pick up maps and printed information for destinations you’ll be visiting later in your trip. Be aware that TI phone numbers for some towns often simply connect you to a centralized national tourist office, with staff that may not have the “local” knowledge you are seeking.

In Dublin, try to get everything you’ll need for all of Ireland in one stop at the TI (see here). The general nationwide tourist-information phone number for travelers calling from within Ireland is 1-850-230-330 (office open Mon-Sat 9:00-17:00, closed Sun).

Emergency and Medical Help: In Ireland, dial 999 for police or a medical emergency. If you get sick, do as the locals do and go to a pharmacist for advice. Or ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services.

Theft or Loss: To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy (see here). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them (see “Damage Control for Lost Cards” on here). File a police report, either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for lost or stolen rail passes or travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport or credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help.

Time Zones: Ireland, which is one hour earlier than most of continental Europe, is five/eight hours ahead of the East/West coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Ireland and Europe “spring forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after most of North America) and “fall back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). For a handy online time converter, see www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

Business Hours: In Ireland, most stores are open Monday through Saturday from roughly 10:00 to 17:30, with a late night on Wednesday or Thursday (until 19:00 or 20:00), depending on the neighborhood. Saturdays are virtually weekdays, with earlier closing hours and no rush hour (though transportation connections can be less frequent than on weekdays). Sundays have the same pros and cons as they do for travelers in the US: Sightseeing attractions are generally open (with limited hours), while banks and many shops are closed. You’ll notice special events, limited public transportation, no rush hours, and street markets lively with shoppers. Friday and Saturday evenings are rowdy; Sunday evenings are quiet.

Watt’s Up? Europe’s electrical system is 220 volts, instead of North America’s 110 volts. Most newer electronics (such as laptops, battery chargers, and hair dryers) convert automatically, so you won’t need a converter, but you will need an adapter plug with three square prongs, sold inexpensively at travel stores in the US. Avoid bringing older appliances that don’t automatically convert voltage; instead, buy a cheap replacement in Europe. Low-cost hair dryers and other small appliances are sold at Dunnes and Tesco stores in bigger cities; ask your hotelier for the closest shop.

Discounts: Discounts for sights (called “concessions” in Ireland) are generally not listed in this book. However, many Irish sights offer discounts for youths (up to age 18), students (with proper identification cards, www.isic.org), families, seniors (loosely defined as retirees or those willing to call themselves seniors), and groups of 10 or more. Always ask. Some discounts are available only for citizens of the European Union (EU).

Laundry: If you’re not planning to wash your clothes in your hotel sink, it’s a good idea to plan ahead for laundry. Basic wash-and-wear clothes have nothing to fear from an Irish launderette (but don’t tempt fate with your favorite silk shirt—it might come back leprechaun-size). At most launderettes, you drop off your load first thing in the morning and pick it up late that afternoon (washed, dried, and kind-of folded). This works well for travelers—the savings from doing it yourself are not worth the lost sightseeing time. Note that late-morning drop-off may delay delivery until the next day, and most places are closed on Sunday; a Monday morning pick-up time may cramp your plans. Confirm closing time when you drop off, and set an alarm to remind you to pick up.

Here’s my basic strategy for using money in Europe:

• Upon arrival, head for a cash machine (ATM) at the airport and load up on local currency, using a debit card with low international transaction fees.

• Withdraw large amounts at each transaction (to limit fees) and keep your cash safe in a money belt.

• Pay for most items with cash.

• Pay for larger purchases with a credit card with low (or no) international fees.

Although credit cards are widely accepted in Europe, day-to-day spending is generally more cash-based than in the US. I find cash is the easiest—and sometimes only—way to pay for cheap food, bus fare, taxis, tips, and local guides. Some businesses (especially smaller ones, such as B&Bs and mom-and-pop cafés and shops) may charge you extra for using a credit card—or might not accept credit cards at all. Having cash on hand helps you out of a jam if your card randomly doesn’t work.

I use my credit card to book and pay for hotel reservations, to buy advance tickets for events or sights, and to cover major expenses (such as car rentals or plane tickets). It can also be smart to use plastic near the end of your trip, to avoid another visit to the ATM.

I pack the following and keep it all safe in my money belt.

Debit Card: Use this at ATMs to withdraw local cash.

Credit Card: Use this to pay for larger items (at hotels, larger shops and restaurants, travel agencies, car-rental agencies, and so on).

Backup Card: Some travelers carry a third card (debit or credit; ideally from a different bank), in case one gets lost, demagnetized, eaten by a temperamental machine, or simply doesn’t work.

US Dollars: I carry $100-200 US dollars as a backup. While you won’t use it for day-to-day purchases, American cash in your money belt comes in handy for emergencies, such as if your ATM card stops working.

What NOT to Bring: Resist the urge to buy euros and pounds before your trip or you’ll pay the price in bad stateside exchange rates. Wait until you arrive to withdraw money. I’ve yet to see a European airport that didn’t have plenty of ATMs.

Use this pre-trip checklist.

Know your cards. Debit cards from any major US bank will work in any standard European bank’s ATM (ideally, use a debit card with a Visa or MasterCard logo). As for credit cards, Visa and MasterCard are universal, American Express is less common, and Discover is unknown in Europe.

Know your PIN. Make sure you know the numeric, four-digit PIN for all of your cards, both debit and credit. Request it if you don’t have one and allow time to receive the information by mail.

All credit and debit cards now have chips that authenticate and secure transactions. Europeans insert their chip cards into the payment machine slot, then enter a PIN. American cards should work in most transactions without a PIN—but may not work at self-service machines at train stations, toll booths, gas pumps, or parking lots. I’ve been inconvenienced a few times by self-service payment machines in Europe that wouldn’t accept my card, but it’s never caused me serious trouble.

If you’re concerned, a few banks offer a chip-and-PIN card that works in almost all payment machines, including those from Andrews Federal Credit Union (www.andrewsfcu.org) and the State Department Federal Credit Union (www.sdfcu.org).

Report your travel dates. Let your bank know that you’ll be using your debit and credit cards in Europe, and when and where you’re headed.

Adjust your ATM withdrawal limit. Find out how much you can take out daily and ask for a higher daily withdrawal limit if you want to get more cash at once. Note that European ATMs will withdraw funds only from checking accounts; you’re unlikely to have access to your savings account.

Ask about fees. For any purchase or withdrawal made with a card, you may be charged a currency conversion fee (1-3 percent), a Visa or MasterCard international transaction fee (1 percent), and—for debit cards—a $2-5 transaction fee each time you use a foreign ATM (some US banks partner with European banks, allowing you to use those ATMs with no fees—ask).

If you’re getting a bad deal, consider getting a new debit or credit card. Reputable no-fee cards include those from Capital One, as well as Charles Schwab debit cards. Most credit unions and some airline loyalty cards have low-to-no international transaction fees.

European cash machines have English-language instructions and work just like they do at home—except they spit out local currency instead of dollars, calculated at the day’s standard bank-to-bank rate.

In most places, ATMs are easy to locate. When possible, withdraw cash from a bank-run ATM located just outside that bank. Ideally use it during the bank’s opening hours; if your card is munched by the machine, you can go inside for help.

If your debit card doesn’t work, try a lower amount—your request may have exceeded your withdrawal limit or the ATM’s limit. If you still have a problem, try a different ATM or come back later—your bank’s network may be temporarily down.

Avoid “independent” ATMs, such as Travelex, Euronet, Moneybox, Cardpoint, and Cashzone. These have high fees, can be less secure than a bank ATM, and may try to trick users with “dynamic currency conversion” (see below).

Avoid exchanging money in Europe; it’s a big rip-off. In a pinch you can always find exchange desks at major train stations or airports—convenient but with crummy rates. Banks in some countries may not exchange money unless you have an account with them.

US cards no longer require a signature for verification, but don’t be surprised if a European card reader generates a receipt for you to sign. Some card readers will accept your card as is; others may prompt you to enter your PIN (so it’s important to know the code for each of your cards). If a cashier is present, you should have no problems.

At self-service payment machines (transit-ticket kiosks, parking, etc.), results are mixed, as US cards may not work for unattended transactions. If your card won’t work, look for a cashier who can process your card manually—or pay in cash.

Drivers Beware: Be aware of potential problems using a US card to fill up at an unattended gas station, enter a parking garage, or exit a toll road. Carry cash and be prepared to move on to the next gas station if necessary. When approaching a toll plaza, use the “cash” lane.

Some European merchants and hoteliers cheerfully charge you for converting your purchase price into dollars. If it’s offered, refuse this “service” (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC). You’ll pay extra for the expensive convenience of seeing your charge in dollars. Some ATM machines also offer DCC, often in confusing or misleading terms. If an ATM offers to “lock in” or “guarantee” your conversion rate, choose “proceed without conversion.” Other prompts might state, “You can be charged in dollars: Press YES for dollars, NO for euros or pounds.” Always choose the local currency.

Pickpockets target tourists. To safeguard your cash, wear a money belt—a pouch with a strap that you buckle around your waist like a belt and tuck under your clothes. Keep your cash, credit cards, and passport secure in your money belt, and carry only a day’s spending money in your front pocket or wallet.

Before inserting your card into an ATM, inspect the front. If anything looks crooked, loose, or damaged, it could be a sign of a card-skimming device. When entering your PIN, carefully block other people’s view of the keypad.

Don’t use a debit card for purchases. Because a debit card pulls funds directly from your bank account, potential charges incurred by a thief will stay on your account while the fraudulent use is investigated by your bank.

While traveling, to access your accounts online, be sure to use a secure connection (see here).

If you lose your credit or debit card, report the loss immediately to the respective global customer-assistance centers. Call these 24-hour US numbers collect: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111). In the Republic of Ireland, to make a collect call to the US, dial 1-800-550-000. In Northern Ireland, dial 0-800-89-0011. Press zero or stay on the line for an English-speaking operator. European toll-free numbers (listed by country) can be found at the websites for Visa and MasterCard.

You’ll need to provide the primary cardholder’s identification-verification details (such as birth date, mother’s maiden name, or Social Security number). You can generally receive a temporary card within two or three business days in Europe (see www.ricksteves.com/help for more).

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50.

Tipping in Ireland isn’t as automatic and generous as it is in the US. For special service, tips are appreciated, but not expected. As in the US, the proper amount depends on your resources, tipping philosophy, and the circumstances, but some general guidelines apply.

Restaurants: At a pub or restaurant with waitstaff, check the menu or your bill to see if the service is included; if not, tip about 10 percent. At pubs where you order food at the counter, a tip is not expected but is appreciated.

Taxis: For a typical ride, round up your fare a bit (for instance, if the fare is €9, give €10). If the cabbie hauls your bags and zips you to the airport to help you catch your flight, you might want to toss in a little more. But if you feel like you’re being driven in circles or otherwise ripped off, skip the tip.

Services: In general, if someone in the tourism or service industry does a super job for you, a small tip of a euro or two is appropriate...but not required. If you’re not sure whether (or how much) to tip, ask a local for advice.

Wrapped into the purchase price of your Irish souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT); it’s 23 percent in the Republic and 20 percent in Northern Ireland. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase more than €30/£30 (about $36/$40) worth of goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. Typically, you must ring up the minimum at a single retailer—you can’t add up your purchases from various shops to reach the required amount. (If the store ships the goods to your US home, VAT is not assessed on your purchase.)

Getting your refund is straightforward...and worthwhile if you spend a significant amount on souvenirs.

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document, called a “Tax-Free Shopping Cheque.” You’ll have to present your passport. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. Process your VAT document at your last stop in the European Union (such as at the airport) with the customs agent who deals with VAT refunds. Arrive an additional hour before you need to check in to allow time to find the customs office—and to stand in line. Some customs desks are positioned before airport security; confirm the location before going through security.

It’s best to keep your purchases in your carry-on. If they’re too large or dangerous to carry on (such as knives), pack them in your checked bags and alert the check-in agent. You’ll be sent (with your tagged bag) to a customs desk outside security; someone will examine your bag, stamp your paperwork, and put your bag on the belt. You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your new Irish sweater, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. Many merchants work with a service, such as Global Blue or Premier Tax Free, that have offices at major airports, ports, or border crossings (either before or after security, probably strategically located near a duty-free shop). These services, which extract a 4 percent fee, can refund your money immediately in cash or credit your card (within two billing cycles). Other refund services may require you to mail the documents from home, or more quickly, from your point of departure (using an envelope you’ve prepared in advance or one that’s been provided by the merchant). You’ll then have to wait—it can take months.

You can take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 31 days. Many processed and packaged foods are allowed, including vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. Fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed, with exceptions for some canned items. As for alcohol, you can bring in one liter duty-free (it can be packed securely in your checked luggage, along with any other liquid-containing items).

To bring alcohol (or liquid-packed foods) in your carry-on bag on your flight home, buy it at a duty-free shop at the airport. You’ll increase your odds of getting it onto a connecting flight if it’s packaged in a “STEB”—a secure, tamper-evident bag. But stay away from liquids in opaque, ceramic, or metallic containers, which usually cannot be successfully screened (STEB or no STEB).

For details on allowable goods, customs rules, and duty rates, visit http://help.cbp.gov.

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Ireland’s finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

A good map is essential for efficient navigation while sightseeing. The maps in this book are concise and simple, designed to help you locate recommended destinations, sights, and local TIs, where you can pick up more in-depth maps. Maps with even more detail are sold at newsstands and bookstores.

Train travelers do fine with a simple rail map (available as part of the free Intercity Timetable found at Irish train stations) and city maps from the TI offices. (You can get free maps of Dublin and Ireland from the national tourist-office websites before you go; see “Tourist Information” at the beginning of this chapter.)

You can also use a mapping app on your mobile device. Be aware that pulling up maps or looking up turn-by-turn walking directions on the fly requires an Internet connection: To use this feature, it’s smart to get an international data plan (see here). With Google Maps or City Maps 2Go, it’s possible to download a map while online, then go offline and navigate without incurring data-roaming charges, though you can’t search for an address or get real-time walking directions. A handful of other apps—including Apple Maps, OffMaps, Maps.me, and Navfree—also allow you to use maps offline.

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your must-see sights. For a one-stop look at opening hours, see the “At a Glance” sidebars for Dublin, Dingle, and Belfast. Most sights keep stable hours, but you can easily confirm the latest by checking with the TI or visiting museum websites.

Don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know when a place will close unexpectedly for a holiday, strike, or restoration. Many museums are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Labor Day (first Monday in May). A list of holidays is on here; check online for possible museum closures during your trip. In summer, some sights may stay open late; in the off-season, hours may be shorter.

Going at the right time helps avoid crowds. This book offers tips on the best times to see specific sights. Try visiting popular sights very early or very late. Make that first sight of the day the one that is the most physically or mentally demanding, while you’ve still got wind in your sails. Evening visits are usually peaceful, with fewer crowds.

If you plan to hire a local guide, reserve ahead by email. Popular guides can get booked up.

Study up. To get the most out of the self-guided walks and sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit.

Here’s what you can typically expect:

Entering: Be warned that you may not be allowed to enter if you arrive less than 30 to 60 minutes before closing time. And guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last.

Many sights have a security check, where you must open your bag or send it through a metal detector. Allow extra time for these lines in your planning. Some sights require you to check daypacks and coats. (If you’d rather not check your daypack, try carrying it tucked under your arm like a purse as you enter.)

Photography: If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask a guard. Generally, taking photos without a flash or tripod is allowed. Some sights ban photos altogether; others ban selfie sticks.

Temporary Exhibits: Museums may show special exhibits in addition to their permanent collection. Some exhibits are included in the entry price, while others come at an extra cost (which you may have to pay even if you don’t want to see the exhibit).

Expect Changes: Artwork can be on tour, on loan, out sick, or shifted at the whim of the curator. Pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask museum staff if you can’t find a particular item.

Audioguides and Apps: Many sights rent audioguides, which generally offer dry-but-useful recorded descriptions (sometimes included with admission). If you bring your own earbuds, you can enjoy better sound and avoid holding the device to your ear. To save money, bring a Y-jack and share one audioguide with your travel partner. Museums and sights often offer free apps that you can download to your mobile device (check their websites).

Services: Important sights may have a reasonably priced on-site café or cafeteria (handy places to rejuvenate during a long visit). The WCs at sights are free and generally clean.

Before Leaving: At the gift shop, scan the postcard rack or thumb through a guidebook to be sure that you haven’t overlooked something that you’d like to see.

Every sight or museum offers more than what is covered in this book. Use the information in this book as an introduction—not the final word.

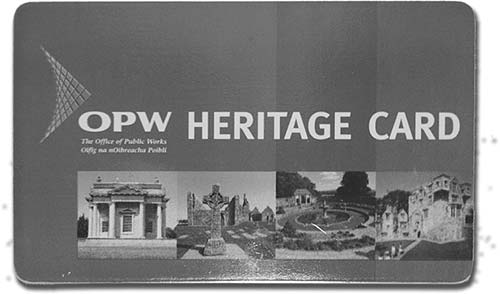

Ireland offers two passes (each covering a different set of sights) that can save you money. Both are smart, although the second packs more punch for two people traveling together (2-for-1 entries for couples as compared to 10-25 percent off for individuals).

Heritage Card: This pass gets you into 98 historical monuments, gardens, and parks maintained by the OPW (Office of Public Works) in the Republic of Ireland. It will pay off if you visit eight or more included sights over the course of your trip (€40; seniors age 60 and older-€30, students-€10, families-€90, covers entry to all Heritage sights for one year, comes with handy map and list of sights’ hours and prices, purchase at first Heritage sight you visit, cash only, tel. 01/647-6592, www.heritageireland.ie, heritagecard@opw.ie). People traveling by car are most likely to get their money’s worth out of the card.

An energetic sightseer with three weeks in Ireland will probably pay to see nearly all 20 of the following sights (covered in this book). Without the Heritage Card, your costs will add up fast, and you’ll waste time buying tickets. (Be aware that advance reservations are recommended for both Kilmainham Gaol and Brú na Bóinne.)

• Dublin Castle-€10

• Kilmainham Gaol-€8 (Dublin)

• Brú na Bóinne (Knowth and Newgrange tombs and Visitors Centre-€13—Boyne Valley)

• Battle of the Boyne-€5

• Hill of Tara-€5 (Boyne Valley)

• Old Mellifont Abbey-€5 (Boyne Valley)

• Trim Castle-€5 (Boyne Valley)

• Glendalough Visitors Centre-€5 (Wicklow Mountains)

• Kilkenny Castle-€8

• Rock of Cashel-€8

• Reginald’s Tower-€5 (Waterford)

• Charles Fort-€5 (Kinsale)

• Desmond Castle-€5 (Kinsale)

• Muckross House-€9 (near Killarney)

• Derrynane House-€5 (Ring of Kerry)

• Garnish Island Gardens-€5 (near Kenmare)

• Great Blasket Centre-€5 (near Dingle)

• Ennis Friary-€5 (Ennis)

• Dun Aengus-€5 (Inishmore, Aran Islands)

• Glenveagh Castle and National Park-€7 (Donegal)

Together these sights total €128; a pass saves you €88 per person over paying individual entrance fees. Note that scheduled tours given by OPW guides at any of these sites are included in the price of admission—regardless of whether you have the Heritage Card. The card covers no sights in Northern Ireland.

Heritage Island Visitor Attraction Map: Ambitious travelers covering more ground can grab this free map adorned with discount coupons (get it at any TI or participating site; skip the €8.45 accompanying 56-page booklet sold online). The map doesn’t overlap with the above Heritage Card sights and provides a variety of discounts (usually 2-for-1 entries, but occasionally 10-25 percent off) at 88 sights in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. This is a great no-brainer addition, especially for two people traveling together. At some sites that already have free admission, you may get 10 percent off purchases at their shop or café. Study the full list of sights first (tel. 01/775-3870, www.heritageisland.com).

Discounted sights on this map include:

• Trinity College Library (Book of Kells, Dublin)

• St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Dublin)

• Dublin City Hall

• Dublinia

• Guinness Storehouse (Dublin)

• Jeanie Johnston Tall Ship and Famine Museum (Dublin)

• Irish National Stud (Kildare)

• Powerscourt Gardens (Enniskerry)

• Avondale House (Wicklow Mountains)

• Dunbrody Famine Ship (New Ross)

• Waterford Crystal Visitor Centre

• Blarney Castle (County Cork)

• Burren Centre (Kilfenora)

• Aillwee Cave (Burren)

• Atlantic Edge exhibit (Cliffs of Moher)

• Clare Museum (Ennis)

• Kylemore Abbey (Letterfrack)

• Strokestown Park National Famine Museum (Strokestown)

• Mount Stewart House (near Bangor)

• Titanic Belfast (Belfast)

• Ulster Museum (Belfast)

• Ulster Folk Park and Transport Museum (Cultra)

• Belleek Pottery Visitors Centre (Belleek)

• Ulster American Folk Park (Omagh)

I favor hotels and restaurants that are handy to your sightseeing activities. Rather than list hotels scattered throughout a city, I choose hotels in my favorite neighborhoods. My recommendations run the gamut, from dorm beds to fancy rooms with all the comforts. Outside of Dublin you can expect to find good doubles for $100-150, including tax and a cooked breakfast.

Extensive and opinionated listings of good-value rooms are a major feature of this book’s Sleeping sections. I like places that are clean, central, relatively quiet at night, reasonably priced, friendly, small enough to have a hands-on owner or manager and stable staff, and run with a respect for Irish traditions. I’m more impressed by a convenient location and a fun-loving philosophy than flat-screen TVs and a fancy gym. Most places I recommend fall short of perfection. But if I can find a place with most of these features, it’s a keeper.

Book your accommodations as soon as your itinerary is set, especially to stay at one of my top listings or if you’ll be traveling during busy times. Also reserve in advance for Dublin for any weekend, for Galway during its many peak-season events, and for Dingle throughout July and August. See here for a list of major holidays and festivals throughout Ireland; for tips on making reservations, see here.

Some people make reservations as they travel, calling hotels and B&Bs a few days to a week before their arrival. If this is you, understand that beggars can’t be choosers and many options might be booked up. If you anticipate crowds (worst weekdays at business destinations and weekends at tourist locales), on the day you want to check in, call hotels at about 9:00 or 10:00, when the receptionist knows who’ll be checking out and which rooms will be available. Some apps—such as HotelTonight.com—specialize in last-minute rooms, often at business-class hotels in big cities.

The Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland have banned smoking in the workplace (pubs, offices, taxicabs, etc.), but some hotels still have a floor or two of rooms where guests are allowed to smoke. If you don’t want a room that a smoker might have occupied before you, let the hotelier know when you make your reservation. All of my recommended B&Bs prohibit smoking. Even in places that allow smoking in the sleeping rooms, breakfast rooms are nearly always smoke-free.

Loud and rowdy Irish stag/hen (bachelor/bachelorette) parties are plentiful on weekends. This enthusiastic, alcohol-assisted merriment can interfere with a much-needed night’s sleep. If you’re a light sleeper, bring earplugs and think twice before booking a weekend room in a hotel with a pub on the ground floor. Steer clear of establishments that trumpet “stags and hens welcome” on their websites.

I’ve categorized my recommended accommodations based on price, indicated with a dollar-sign rating (see sidebar). The price ranges suggest an estimated cost for a one-night stay in a double room with a private toilet and shower in high season, include a hearty breakfast, and assume you’re booking directly with the hotel (not through a booking site, which extracts a commission). Room prices can fluctuate significantly with demand and amenities (size, views, room class, and so on), but these relative price categories remain constant.

Room rates are especially volatile at larger hotels that use “dynamic pricing” to set rates. Prices can skyrocket during festivals and conventions, while business hotels can have deep discounts on weekends when demand plummets. Of the many hotels I recommend, it’s difficult to say which will be the best value on a given day—until you do your homework.

Once your dates are set, check the specific price for your preferred stay at several hotels. You can do this either by comparing prices on a site such as Hotels.com or Booking.com, or by checking the hotels’ own websites. To get the best deal, contact my family-run hotels directly by phone or email. When you go direct, the owner avoids the 20 percent commission, giving them wiggle room to offer you a discount, a nicer room, or free breakfast if it’s not already included (see the “Making Hotel Reservations” sidebar, later). If you prefer to book online or are considering a hotel chain, it’s to your advantage to use the hotel’s website.

Some hotels offer a discount to those who pay cash or stay longer than three nights. To cut costs further, try asking for a cheaper room (for example, with a shared bathroom or no window) or offer to skip breakfast (if included).

Additionally, some accommodations offer a special discount for Rick Steves readers, indicated in this guidebook by the abbreviation “RS%.” Discounts vary: Ask for details when you reserve. Generally, to qualify you must book direct (that is, not through a booking site), mention this book when you reserve, show this book upon arrival, and sometimes pay cash or stay a certain number of nights. In some cases, you may need to enter a discount code (which I’ve provided in the listing) in the booking form on the hotel’s website. Rick Steves discounts apply to readers with ebooks as well as printed books. Understandably, discounts do not apply to promotional rates.

When establishing prices, confirm if the charge is per person or per room (if a price is too good to be true, it’s probably per person). Because many places in Ireland charge per person, small groups often pay the same for a single and a double as they would for a triple. In this book, I’ve categorized hotels based on the per-room price, not per person.

Many US travel agents sell vouchers for lodging in Ireland. In essence, you’re paying ahead of time for your lodging, with the assurance that you’ll be staying in B&Bs and guesthouses that live up to certain standards. I don’t recommend buying these, since your choices will be limited to only the places in Ireland that accept vouchers. Sure, there are hundreds in the program to choose from. But in this guidebook, I list any place that offers a good value—a useful location, nice hosts, and a comfortable and clean room—regardless of what club they do or don’t belong to. Lots of great B&Bs choose not to participate in the voucher program because they have to pay to be part of it, slicing into their already thin profit. And many Irish B&B owners lament the long wait between the date a traveler stays with them and the date the voucher company reimburses them. In short, skip it. The voucher program is just an expensive middleman between you and the innkeeper.

Ireland has a rating system for hotels and B&Bs. These stars and shamrocks are supposed to imply quality, but I find that they mean only that the place sporting symbols is paying dues to the tourist board. These rating systems often have little to do with value: One of my favorite Irish B&Bs (also loved by readers) will never be tourist-board approved because it has no dedicated breakfast room (a strict requirement in the eyes of the board). Instead, guests sit around a large kitchen table and enjoy a lively chat with the friendly hosts as they cook breakfast 10 feet away.

Know the terminology: “Twin” means two single beds, “double” means one double bed. If you’ll take either one, let them know, or you might be needlessly turned away. An “en suite” room has a bathroom (toilet and shower/tub) inside the room; a room with a “private bathroom” can mean that the bathroom is all yours, but it’s across the hall; and a “standard” room has access to a bathroom down the hall that’s shared with other rooms. Figuring there’s little difference between “en suite” and “private” rooms, some places charge the same for both. If you want your own bathroom inside the room, request “en suite.” If money’s tight, ask for a standard room. You’ll almost always have a sink in your room, and as more rooms go “en suite,” the hallway bathroom is shared with fewer standard rooms.

Some hotels can add an extra bed (for a small charge) to turn a double into a triple; some offer larger rooms for four or more people (I call these “family rooms” in the listings). If there’s space for an extra cot, they’ll cram it in for you. In general, a triple room is cheaper than the cost of a double and a single. Three or four people can economize by requesting one big room.

Most hotels offer family deals, which means that parents with young children can easily get a room with an extra child’s bed or a discount for a larger room. Call to negotiate the price. Teenagers are generally charged as adults. Kids under five sleep almost free.

Note that to be called a “hotel,” a place technically must have certain amenities, including a 24-hour reception (though this rule is loosely applied). TVs are standard in rooms.

Arrival and Check-In: Hotel elevators are becoming more common, though some older buildings still lack them. You may have to climb a flight of stairs to reach the elevator (if so, you can ask the front desk for help carrying your bags up). Elevators are typically very small—pack light, or you may need to send your bags up without you.

When you check in, the receptionist will normally ask for your passport and keep it for anywhere from a couple of minutes to a couple of hours. The EU requires that hotels collect your name, nationality, and ID number. Relax. Americans are notorious for making this chore more difficult than it needs to be.

If you’re arriving in the morning, your room probably won’t be ready. Drop your bag safely at the hotel and dive right into sightseeing.

In Your Room: More pillows and blankets are usually in the closet or available on request. Towels and linens aren’t always replaced every day. Hang your towel up to dry.

Most hotel rooms have a TV, telephone, and free Wi-Fi (although in old buildings with thick walls, the Wi-Fi signal doesn’t always make it to the rooms; sometimes it’s only available in the lobby). There’s often a guest computer with Internet access in the lobby. Simpler places rarely have a room phone, but often have free Wi-Fi.

Breakfast and Meals: Small hotels and B&Bs serve a hearty “Irish fry” breakfast (more about B&B breakfasts later). Because B&Bs owners are often also the cook, there’s usually a limited time span when breakfast is served (typically about an hour, starting at about 8:00). Modern hotels usually have an attached restaurant.

Hotelier Help: Hoteliers can be a good source of advice. Most know their city well, and can assist you with everything from public transit and airport connections to finding a good restaurant, the nearest launderette, or a late-night pharmacy.

To guard against theft in your room, keep valuables out of sight. Some rooms come with a safe, and other hotels have safes at the front desk. I’ve never bothered using one and in a lifetime of travel, I’ve never had anything stolen from my room.

Checking Out: While it’s customary to pay for your room upon departure, it can be a good idea to settle your bill the day before, when you’re not in a hurry and while the manager’s in. That way you’ll have time to discuss and address any points of contention.

Hotel Hassles: Even at the best places, mechanical breakdowns occur: Sinks leak, hot water turns cold, toilets may gurgle or smell, the Wi-Fi goes out, or the air-conditioning dies when you need it most. Report your concerns clearly and calmly at the front desk. For more complicated problems, don’t expect instant results. Above all, keep a positive attitude. Remember, you’re on vacation. If your hotel or B&B is a disappointment, spend more time out enjoying the place you came to see.

If you suspect night noise will be a problem (if, for instance, your room is over a rowdy pub), ask for a quieter room in the back or on an upper floor. Pubs are plentiful and packed with revelers on weekend nights. (James Joyce once said it would be a good puzzle to try to walk across Dublin without passing a pub.)

Compared to hotels, bed-and-breakfast places give you double the cultural intimacy for half the price. While you may lose some of the conveniences of a hotel—such as lounges, in-room phones, frequent bedsheet changes, and being able to pay with a credit card—I happily make the trade-off for the lower rates and personal touches. If you have a reasonable but limited budget, skip hotels and go the B&B way. In 2019, you’ll generally pay €45-70 (about $55-80) per person for a double room in a B&B in Ireland. Prices include a big cooked breakfast. The amount of coziness, doilies, tea, and biscuits tossed in varies tremendously.

You’ll likely need to pay cash for your room. Think ahead so you have enough cash to pay up when you check out. Paying in cash helps keep prices down: Some of my favorite B&Bs tell me the fee for a small business to accept credit cards can exceed €750 a year (money they likely would not make back by offering the service).

B&Bs range from large guesthouses with 10-15 rooms to small homes renting out a couple of spare bedrooms, but typically have six rooms or fewer. A “townhouse” or “house” is like a big B&B or a small family-run hotel—with fewer amenities but more character than a hotel. The philosophy of the management determines the character of a place more than its size and facilities offered. Avoid places run as a business by absentee owners (their hired hands often don’t provide the level of service that pride of ownership brings). My top listings are run by people who enjoy welcoming the world to their breakfast table.

Book direct. If you buy the lodging vouchers sold by many US travel agents, you’ll only be taking money from the innkeeper and putting it in the pocket of a middleman. If you have a local TI book a room for you or use a website like Booking.com, the B&B will pay a 15 percent commission. But if you book direct, the B&B gets it all, and you’ll have a better chance of getting a discount. I have negotiated special discounts with this book (often for payment in cash, and always for booking direct).

Small hotels and B&Bs come with their own etiquette and quirks. Keep in mind that B&B owners are subject to the whims of their guests—if you’re getting up early, so are they; and if you check in late, they’ll wait up for you. It’s polite to call ahead to confirm your reservation the day before and give them a rough estimate of your arrival time. This allows your hosts to plan their day and run errands before or after you arrive...and also allows them to give you specific directions for driving or walking to their place. If you are arriving past the agreed time, please call and let them know.

A few tips: B&B proprietors are selective as to whom they invite in for the night. At some B&Bs, children are not welcome. Risky-looking people (two or more single men are often assumed to be troublemakers) find many places suddenly full. If you’ll be staying for more than one night, you are a “desirable.” In popular weekend-getaway spots, you’re unlikely to find a place to take you for Saturday night only. If my listings are full, ask for guidance. (Mentioning this book can help.) Owners usually work together and can call up an ally to land you a bed.

B&Bs serve a hearty “Irish fry” breakfast (for more about Irish breakfast, see “Eating,” later in this chapter). You’ll quickly figure out which parts of the “fry” you do and don’t like. B&B owners prefer to know this up front, rather than serving you the whole shebang and throwing out uneaten food. Because your B&B owner is also the cook, there’s usually a quite limited time span when breakfast is served (typically about an hour, starting at about 8:00—make sure you know the exact time before you turn in for the night). It’s an unwritten rule that guests shouldn’t show up at the very end of the breakfast period and expect a full cooked breakfast. If you do arrive at the last minute (or if you need to leave before breakfast is served), most B&B hosts are happy to let you help yourself to cereal, fruit or juice, and coffee; ask politely if it’s possible.

Some B&Bs stock rooms with an electric kettle, along with cups, tea bags, and coffee packets (if you prefer decaf, buy a jar at a grocery, and dump the contents into a baggie for easy packing).

B&Bs are not hotels. Think of your host as a friendly acquaintance who’s invited you to stay in her home, rather than someone you’re paying to wait on you. Americans often assume they’ll get new towels each day. The Irish don’t. Hang them up to dry and reuse. And pack a washcloth (many Irish B&Bs don’t provide them).

Electrical outlets sometimes have switches that turn the current on or off; if your electrical appliance isn’t working, flip the switch at the outlet. When you unplug your appliance, don’t forget your adapter—most B&Bs have boxes of various adapters and converters that guests have left behind (which is handy if you left yours at the last place).

Most B&Bs come with thin walls and doors. This can make for a noisy night, especially with people walking down the hall to use the bathroom. If you’re a light sleeper, bring earplugs. And please be quiet in the halls and in your rooms (gently shut your door, talk softly, and keep the TV volume low)...those of us getting up early will thank you for it.

Virtually all rooms have sinks. You’ll likely encounter unusual bathroom fixtures. The “pump toilet” has a flushing handle that doesn’t kick in unless you push it just right: too hard or too soft, and it won’t go. (Be decisive but not ruthless.) There’s also the “dial-a-shower,” an electronic box under the showerhead where you’ll turn a dial to select the heat of the water, and (sometimes with a separate dial or button) turn on or shut off the flow of water. If you can’t find the switch to turn on the shower, it may be just outside the bathroom.

Your B&B bedroom might not include a phone. Some B&B owners will allow you to use their phone, but understandably they don’t want to pay for long-distance charges. If you must use their phone, keep the call short (5-10 minutes max). If you plan to stay in B&Bs and make frequent calls, consider bringing a mobile phone or buying one in Ireland (see here). At a B&B, some rooms might have better Wi-Fi reception than others; usually the ground-floor lobby or breakfast room is your best bet.

A few B&B owners are also pet owners. And, while pets are rarely allowed into guest rooms, and B&B proprietors are typically very tidy, those with pet allergies might be bothered. I’ve tried to list which B&Bs have pets, but if you’re allergic, ask about pets when you reserve.

Hotel chains—popular with budget tour groups—offer predictably comfortable, no-frills accommodations at reasonable prices. These hotels are popping up in big cities in Ireland. They can be located near the train station, in the city center, on major arterials, and outside the city center. What you lose in charm, you gain in savings.

I can’t stress this enough: Check online for the cheapest deals. But be sure to go through the hotel’s website rather than an online middleman.

Chain hotels are ideal for families, offering simple, clean, and modern rooms for up to four people (two adults/two children) for €110-165, depending on the location. Note that couples often pay the same price for a room as do families (up to four). Most rooms have a double bed, single bed, five-foot trundle bed, private shower, WC, TV, and Wi-Fi. Hotels usually have an attached restaurant, good security, an elevator, and a 24-hour staffed reception desk. Of course, they’re as cozy as a Motel 6, but many travelers love them. You can book online (be sure to check their websites for deals) or over the phone with a credit card, then pay when you check in. When you check out, just drop off the key, Lee.

The biggies are Jurys Inn (call their hotels directly or book online at www.jurysinns.com), Comfort/Quality Inns (Republic of Ireland tel. 1-800-500-600, Northern Ireland tel. 0800-444-444, US tel. 877-424-6423, www.choicehotels.com), and Travelodge (also has freeway locations for tired drivers, reservation center in Britain tel. 08700-850-950, www.travelodge.co.uk).

A short-term rental—whether an apartment, house, or room in a local’s home—is an increasingly popular alternative, especially if you plan to settle in one location for several nights. For stays longer than a few days, you can usually find a rental that’s comparable to—and cheaper than—a hotel room with similar amenities. Plus, you’ll get a behind-the-scenes peek into how locals live.

Many places require a minimum night stay, and compared to hotels, rentals usually have less-flexible cancellation policies. And you’re generally on your own: There’s no hotel reception desk, breakfast, or daily cleaning service.

Finding Accommodations: Aggregator websites such as Airbnb, FlipKey, Booking.com, and the HomeAway family of sites (HomeAway, VRBO, and VacationRentals) let you browse properties and correspond directly with European property owners or managers. If you prefer to work from a curated list of accommodations, consider using a rental agency such as InterhomeUSA.com or RentaVilla.com. Agency-represented apartments typically cost more, but this method often offers more help and safeguards than booking direct. Both of Ireland’s tourism websites (www.discoverireland.ie and www.discovernorthernireland.com) are reliable sources.

Before you commit, be clear on the details, location, and amenities. I like to virtually “explore” the neighborhood using the Street View feature on Google Maps. Also consider the proximity to public transportation, and how well-connected the property is with the rest of the city. Ask about amenities (elevator, air-conditioning, laundry, Wi-Fi, parking, etc.). Reviews from previous guests can help identify trouble spots.

Think about the kind of experience you want: Just a key and an affordable bed...or a chance to get to know a local? There are typically two kinds of hosts: those who want minimal interaction with their guests, and hosts who are friendly and may want to interact with you. Read the promotional text and online reviews to help shape your decision.

Apartments and Rental Houses: If you’re staying somewhere for four nights or longer, it’s worth considering an apartment—sometimes called a “flat” in Ireland—or rental house (shorter stays aren’t worth the hassle of arranging key pickup, buying groceries, etc.). Apartment or house rentals can be especially cost-effective for groups and families. European apartments, like hotel rooms, tend to be small by US standards. But they often come with laundry machines and small, equipped kitchens, making it easier and cheaper to dine in. If you make good use of the kitchen (and Europe’s great produce markets), you’ll save on your meal budget.

Rooms in Private Homes: Renting a room in someone’s home is a good option for those traveling alone, as you’re more likely to find true single rooms—with just one single bed, and a price to match. Beds range from air-mattress-in-living-room basic to plush-B&B-suite posh. Some places allow you to book for a single night; if staying for several nights, you can buy groceries just as you would in a rental house. While you can’t expect your host to also be your tour guide—or even to provide you with much info—some may be interested in getting to know the travelers who come through their home.

Other Options: Swapping homes with a local works for people with an appealing place to offer, and who can live with the idea of having strangers in their home (don’t assume where you live is not interesting to Europeans). A good place to start is HomeExchange. To sleep for free, Couchsurfing.com is a vagabond’s alternative to Airbnb. It lists millions of outgoing members, who host fellow “surfers” in their homes.

Confirming and Paying: Many places require you to pay the entire balance before your trip. It’s easiest and safest to pay through the site where you found the listing. Be wary of owners who want to take your transaction offline to avoid fees; this gives you no recourse if things go awry. Never agree to wire money (a key indicator of a fraudulent transaction).

Ireland has hundreds of hostels of all shapes and sizes. Choose yours selectively; hostels can be historic castles or depressing tenements, serene and comfy or overrun by noisy school groups.

A hostel provides cheap beds in dorms where you sleep alongside strangers for about €25 per night. Travelers of any age are welcome if they don’t mind dorm-style accommodations and meeting other travelers. Most hostels offer kitchen facilities, guest computers, Wi-Fi, and a self-service laundry. Hostels almost always provide bedding, but the towel’s up to you (though you can usually rent one for a small fee). Family and private rooms are often available.

Independent hostels tend to be easygoing, colorful, and informal (no membership required, www.hostelworld.com). You may pay slightly less by booking direct with the hostel. Ireland’s Independent Holiday Hostels (www.hostels-ireland.com) is a network of independent hostels, requiring no membership and welcoming all ages. All IHH hostels are approved by Fáilte Ireland.

Official hostels are part of Hostelling International (HI) and share an online booking site (www.hihostels.com). HI hostels typically require that you be a member or pay extra per night.

Denis Leary once quipped, “Irish food isn’t cuisine...it’s penance.” For years, Irish food was something you ate to survive rather than to savor. In this country, long considered the “land of potatoes,” the diet reflected the economic circumstances. But times have changed. You’ll find modern Irish cuisine delicious and varied. Expatriate chefs have come home with newly refined tastes, and immigrants have added a world of interesting flavors.

Modern Irish cuisine is skillfully prepared with fresh, local ingredients. Irish beef, lamb, and dairy products are among the EU’s best. And there are streams full of trout and salmon and a rich ocean of fish and shellfish right offshore. While potatoes remain staples, they’re often replaced with rice or pasta in many dishes. Try the local specialties wherever you happen to be eating.

The traditional breakfast, the “Irish Fry” (known in the North as the “Ulster Fry”), is a hearty way to start the day—with juice, tea or coffee, cereal, eggs, bacon, sausage, a grilled tomato, sautéed mushrooms, and optional black pudding (made from pigs’ blood). Toast is served with butter and marmalade. Home-baked Irish soda bread can be an ambrosial eye-opener for those of us raised on Wonder Bread. This meal tides many travelers over until dinner. But there’s nothing un-Irish about skipping the “fry”—few locals actually start their day with this heavy traditional breakfast. You can simply skip the heavier fare and enjoy the cereal, juice, toast, and tea (surprisingly, the Irish drink more tea per capita than the British).

I look for restaurants that are convenient to your hotel and sightseeing. When restaurant-hunting, choose a spot filled with locals, not tourists. Venturing even a block or two off the main drag leads to higher-quality food for less than half the price of the tourist-oriented places. Locals eat better at lower-rent locales.

Picnicking saves time and money. Try boxes of orange juice (pure, by the liter), fresh bread (especially Irish soda bread), tasty Cashel blue cheese, meat, a tube of mustard, local-eatin’ apples, bananas, small tomatoes, a small tub of yogurt (it’s drinkable), rice crackers, trail mix or nuts, plain digestive biscuits (the chocolate-covered ones melt), and any local specialties. At open-air markets and supermarkets, you can get produce in small quantities. Supermarkets often have good deli sections, packaged sandwiches, and sometimes salad bars. Hang on to the half-liter mineral-water bottles (sold everywhere for about €1.50). Buy juice in cheap liter boxes, then drink some and store the extra in your water bottle. I often munch a relaxed “meal on wheels” in a car, train, or bus to save 30 precious minutes for sightseeing.

If you’re driving, pull over and grab a healthy snack at a roadside stand (Ireland’s climate is ideal for strawberries...County Wexford claims the best spring/summer crop).

Tipping: At a sit-down place with table service, tip about 10 percent—unless the service charge is already listed on the bill. If you order at a counter, there’s no need to tip.

I’ve categorized my recommended eateries based on price, indicated with a dollar-sign rating (see sidebar). The price ranges suggest the average price of a typical main course—but not necessarily a complete meal. Obviously, expensive items (like steak and seafood), fine wine, appetizers, and dessert can significantly increase your final bill.

The categories also indicate a place’s personality: Budget eateries include street food, takeaway, order-at-the-counter shops, basic cafeterias, bakeries selling sandwiches, and so on. Moderate eateries are nice (but not fancy) sit-down restaurants, ideal for a straightforward, fill-the-tank meal. Most of my listings fall in this category—great for a good taste of local cuisine on a budget.

Pricier eateries are a notch up, with more attention paid to the setting, presentation, and cuisine. These are ideal for a memorable meal that doesn’t break the bank. This category often includes affordable “destination” or “foodie” restaurants. And splurge eateries are dress-up-for-a-special-occasion-swanky—typically with an elegant setting, polished service, pricey and intricate cuisine, and an expansive (and expensive) wine list.

I haven’t categorized places where you might assemble a picnic, snack, or graze: supermarkets, delis, ice cream-stands, cafés or bars specializing in drinks, chocolate shops, and so on. At classier restaurants, look for “early-bird specials,” which allow you to eat well and affordably, but early (about 17:30-19:00).

If beer is not your cup of tea, don’t wine about it. Pubs are a basic part of the Irish social scene, and whether you’re a teetotaler or a beer-guzzler, they should be a part of your travel here. Whether in rural villages or busy Dublin, a pub (short for “public house”) is an extended living room where, if you don’t mind the stickiness, you can feel the pulse of Ireland.

Smart travelers use pubs to eat, drink, get out of the rain, watch the latest sporting event, and make new friends. Unfortunately, many city pubs have been afflicted with an excess of brass, ferns, and video games. Today the most traditional atmospheric pubs are in Ireland’s countryside and smaller towns.

Pub grub gets better every year—it’s Ireland’s best eating value. But don’t expect high cuisine; this is, after all, comfort food. For about $20, you’ll get a basic hot lunch or dinner in friendly surroundings. Pubs that are attached to restaurants, advertise their food, and are crowded with locals are more likely to have fresh food and a chef than sell lousy microwaved snacks.

Pub menus consist of a hearty assortment of traditional dishes, such as Irish stew (mutton with mashed potatoes, onions, carrots, and herbs), soups and chowders, coddle (bacon, pork sausages, potatoes, and onions stewed in layers), fish-and-chips, collar and cabbage (boiled bacon coated in bread crumbs and brown sugar, then baked and served with cabbage), boxty (potato pancake filled with fish, meat, or vegetables), and champ (potato mashed with milk and onions). Irish soda bread nicely rounds out a meal. In coastal areas, seafood is available, such as mackerel, mussels, and Atlantic salmon. There’s seldom table service in Irish pubs. Order drinks and meals at the bar. Pay as you order, and only tip (by rounding up to avoid excess coinage) if you like the service. Don’t expect every pub to offer grub. Some only have peanuts and potato chips.

I recommend certain pubs to eat in, and your B&B host is usually up-to-date on the best neighborhood pub grub. Ask for advice (but adjust for nepotism and cronyism, which run rampant).

When you say “a beer, please” in an Irish pub, you’ll get a pint of Guinness (the tall blonde in a black dress). If you want a small beer, ask for a glass, which is a half-pint. Never rush your bartender when he’s pouring a Guinness. It’s an almost-sacred two-step process that requires time for the beer to settle.

The Irish take great pride in their beer. At pubs, long hand pulls are used to draw the traditional, rich-flavored “real ales” up from the cellar. These are the connoisseur’s favorites: They’re fermented naturally, vary from sweet to bitter, and often have a hoppy or nutty flavor. Experiment with obscure local microbrews (a small but growing presence on the Irish beer scene). Short hand pulls at the bar mean colder, fizzier, mass-produced, and less interesting keg beers. Stout is dark and more bitter, like Guinness. If you think you don’t like Guinness, try it in Ireland. It doesn’t travel well and is better in its homeland. Murphy’s is a very good Guinness-like stout, but a bit smoother and milder. For a cold, refreshing, basic, American-style beer, ask for a lager, such as Harp. Ale drinkers swear by Smithwick’s (I know I do). Caffrey’s is a satisfying cross between stout and ale. Try the draft cider (sweet or dry)...carefully. The most common spirit is triple-distilled Irish whiskey. Teetotalers can order a soft drink.

Pubs are generally open daily from 11:00 to 23:30 and Sunday from noon to 22:30. Children are served food and soft drinks in pubs (sometimes in a courtyard or the restaurant section). You’ll often see signs behind the bar asking that children vacate the premises by 20:00. You must be 18 to order a beer, and the Gardí (police) are cracking down on pubs that don’t enforce this law.

You’re a guest on your first night; after that, you’re a regular. A wise Irishman once said, “It never rains in a pub.” The relaxed, informal atmosphere feels like a refuge from daily cares. Women traveling alone need not worry—you’ll become part of the pub family in no time.

Craic (pronounced “crack”), Irish for “fun” or “a good laugh,” is the sport that accompanies drinking in a pub. People are there to talk. To encourage conversation, stand or sit at the bar, not at a table.

In 2004, the Irish government passed a law making all pubs in the Republic smoke-free. Smokers now take their pints outside, turning alleys into covered smoking patios. An incredulous Irishman responded to the law by saying, “What will they do next? Ban drinking in pubs? We’ll never get to heaven if we don’t die.”

It’s a tradition to buy your table a round, and then for each person to reciprocate. If an Irishman buys you a drink, thank him by saying, “Go raibh maith agat” (guh rov mah UG-ut). Offer him a toast in Irish—“Slainte” (SLAWN-chuh), the equivalent of “cheers.” A good excuse for a conversation is to ask to be taught a few words of Irish Gaelic.

One of the most common questions I hear from travelers is, “How can I stay connected in Europe?” The short answer is: more easily and cheaply than you might think.

The simplest solution is to bring your own device—mobile phone, tablet, or laptop—and use it just as you would at home (following the tips here, such as connecting to free Wi-Fi whenever possible). Another option is to buy a European SIM card for your mobile phone—either your US phone or one you buy in Europe. Or you can use European landlines and computers to connect. Each of these options is described next, and more details are at www.ricksteves.com/phoning. For a very practical one-hour talk covering tech issues for travelers, see www.ricksteves.com/mobile-travel-skills.

Because dialing instructions vary between the Republic and Northern Ireland, carefully read “How to Dial,” on here.

Here are some budget tips and options.

Sign up for an international plan. Using your cellular network in Europe on a pay-as-you-go basis can add up (about $1.70/minute for voice calls, 50 cents to send text messages, 5 cents to receive them, and $10 to download one megabyte of data). To stay connected at a lower cost, sign up for an international service plan through your carrier. Most providers offer a simple bundle that includes calling, messaging, and data. Your normal plan may already include international coverage (T-Mobile’s does).

Before your trip, call your provider or check online to confirm that your phone will work in Europe, and research your provider’s international rates. Activate the plan a day or two before you leave, then remember to cancel it when your trip’s over.

Use free Wi-Fi whenever possible. Unless you have an unlimited-data plan, you’re best off saving most of your online tasks for Wi-Fi. You can access the Internet, send texts, and even make voice calls over Wi-Fi.

Most accommodations in Europe offer free Wi-Fi, but some—especially expensive hotels—charge a fee. Many cafés (including Starbucks and McDonald’s) have free hotspots for customers; look for signs offering it and ask for the Wi-Fi password when you buy something. You’ll also often find Wi-Fi at TIs, city squares, major museums, public-transit hubs, and airports, and aboard trains and buses.

Minimize the use of your cellular network. Even with an international data plan, wait until you’re on Wi-Fi to Skype, download apps, stream videos, or do other megabyte-greedy tasks. Using a navigation app such as Google Maps over a cellular network can take lots of data, so do this sparingly or use it offline.

Limit automatic updates. By default, your device constantly checks for a data connection and updates apps. It’s smart to disable these features so your apps will only update when you’re on Wi-Fi, and to change your device’s email settings from “auto-retrieve” to “manual” (or from “push” to “fetch”).

When you need to get online but can’t find Wi-Fi, simply turn on your cellular network just long enough for the task at hand. When you’re done, avoid further charges by manually turning off data roaming or cellular data (either works) in your device’s Settings menu. Another way to make sure you’re not accidentally using data roaming is to put your device in “airplane” mode (which also disables phone calls and texts), and then turn your Wi-Fi back on as needed.

It’s also a good idea to keep track of your data usage. On your device’s menu, look for “cellular data usage” or “mobile data” and reset the counter at the start of your trip.

Use Wi-Fi calling and messaging apps. Skype, Viber, FaceTime, and Google+ Hangouts are great for making free or low-cost voice and video calls over Wi-Fi. With an app installed on your phone, tablet, or laptop, you can log on to a Wi-Fi network and contact friends or family members who use the same service. If you buy credit in advance, with some of these services you can call any mobile phone or landline worldwide for just pennies per minute.

Many of these apps also allow you to send messages over Wi-Fi to any other person using that app. Be aware that some apps, such as Apple’s iMessage, will use the cellular network if Wi-Fi isn’t available: To avoid this possibility, turn off the “Send as SMS” feature.

With a European SIM card, you get a European mobile number and access to cheaper rates than you’ll get through your US carrier. This option works well for those who want to make a lot of voice calls or need faster connection speeds than their US carrier provides. Fit the SIM card into a cheap phone you buy in Europe (about $40 from phone shops anywhere), or swap out the SIM card in an “unlocked” US phone (check with your carrier about unlocking it).

SIM cards are sold at mobile-phone shops, department-store electronics counters, some newsstands, and vending machines. Costing about $5-10, they usually include prepaid calling/messaging credit, with no contract and no commitment. Expect to pay $20-40 more for a SIM card with a gigabyte of data. If you travel with this card to other countries in the European Union, there should be no extra roaming fees.

I like to buy SIM cards at a phone shop where there’s a clerk to help explain the options. Certain brands—including Lebara and Lycamobile, both of which are available in multiple European countries—are reliable and especially economical. Ask the clerk to help you insert your SIM card, set it up, and show you how to use it. In some countries, you’ll be required to register the SIM card with your passport as an antiterrorism measure (which may mean you can’t use the phone for the first hour or two).

Find out how to check your credit balance. When you run out of credit, you can top it up at newsstands, tobacco shops, mobile-phone stores, or many other businesses (look for your SIM card’s logo in the window), or online.

It’s possible to travel in Europe without a mobile device. You can make calls from your hotel (or the increasingly rare public phone), and check email or browse websites using public computers.

Most hotels charge a fee for placing calls—ask for rates before you dial. Phones are rare in B&Bs; if there’s no phone in your room, and you have an important, brief call to make, politely ask your hosts if you can use their personal phone.

Public pay phones are hard to find in Northern Ireland, and they’re expensive. To use one, you’ll pay with a major credit card (which you insert into the phone—minimum charge for a credit-card call is £1.20) or coins (have a bunch handy; minimum fee is £0.60). Only unused coins are returned, so put in biggies with caution.

Most hotels have public computers in their lobbies for guests to use; otherwise you may find them at Internet cafés and public libraries (ask your hotelier or the TI for the nearest location). Think ahead, especially if you need to print boarding passes for a flight (Ryanair requires it).

On a European keyboard, use the “Alt Gr” key to the right of the space bar to insert the extra symbol that appears on some keys. If you can’t locate a special character (such as @), simply copy it from a Web page and paste it into your email message.

You can mail one package per day to yourself worth up to $200 duty-free from Europe to the US (mark it “personal purchases”). If you’re sending a gift to someone, mark it “unsolicited gift.” For details, visit www.cbp.gov, select “Travel,” and search for “Know Before You Go.”

The Irish postal service works fine, but for quick transatlantic delivery (in either direction), consider services such as DHL (www.dhl.com). Get stamps at the neighborhood post office, newsstands within fancy hotels, and some minimarts and card shops. Don’t use stamps from the Republic of Ireland on postcards mailed in Northern Ireland (part of the UK), and vice versa.

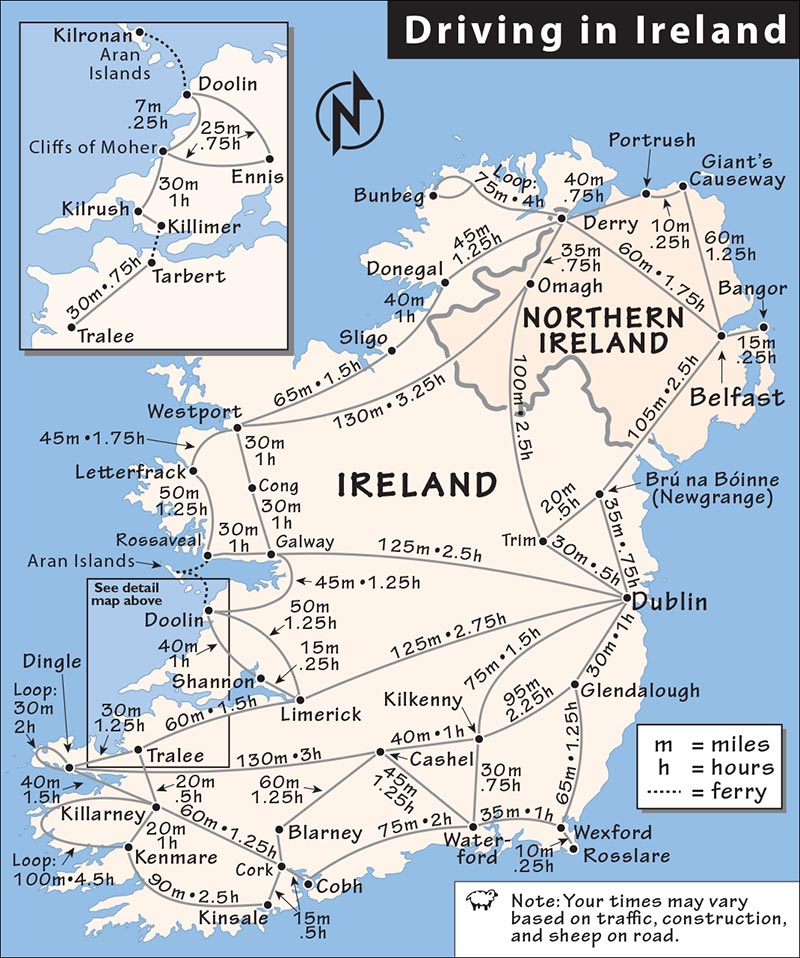

To see all of Ireland, especially the sights with far-flung rural charm, I prefer the freedom of a rental car. Connemara, the Ring of Kerry, the Antrim Coast, County Donegal, County Wexford, and the Boyne Valley are really only worth it if you have wheels.

Cars are best for three or more traveling together (especially families with small kids), those packing heavy, and those scouring the countryside. Trains and buses are best for solo travelers, blitz tourists, city-to-city travelers, and those who don’t want to drive in Ireland.

Ireland has a good train-and-bus system, though departures are not as frequent as the European norm. Most rail lines spoke outward from Dublin, so you’ll need to mix in bus transportation to bridge the gaps. Buses pick you up when the trains let you down.

Given the choice of either a bus or a train between the same two towns, I prefer trains, which are sometimes faster and are not subject to the vehicle traffic that can delay buses (although bus travel can be more direct). Also, unlike bus travel, on a train you can get up and walk around.

The best overall source of schedules for public transportation in the Republic of Ireland as well as Northern Ireland—including rail, cross-country and city buses, and Dublin’s LUAS transit—is the Republic of Ireland’s domestic website: www.discoverireland.ie (select “Getting Around” near the bottom of the home page).

I’ve included a sample itinerary for drivers (with tips and tweaks for those using public transportation) to help you explore Ireland smoothly; you’ll find it on here.

To research Irish rail connections online, you need to access two sites. For the Republic of Ireland, use www.irishrail.ie. For Northern Ireland, use www.translink.co.uk. For train schedules on the rest of the European continent, check www.bahn.com (Germany’s excellent Europe-wide timetable).

It really pays to buy your train tickets online ahead of time. Advance-purchase discounts of up to 50 percent are not unheard of, but online fares fluctuate widely and unpredictably. Online and off, fares are often higher for peak travel on Fridays and Sundays. Remember that the quoted price will be in euros or British pounds. Booking ahead online can also help you avoid long ticket lines in Dublin and elsewhere at busy times.

Be aware that very few Irish train stations have storage lockers.

Rail Passes: For most travelers in Ireland, a rail pass is not very useful. Trains fan out from Dublin to major cities but neglect much of the countryside. But if a pass works for your itinerary, keep in mind that Eurail passes cover all trains in both the Republic and Northern Ireland, and give a 30 percent discount on standard foot-passenger fares for some international ferries. Irish Rail also offers passes covering four consecutive days or five days of travel within a 15-day period in the Republic only (purchase at any major rail station in Ireland, www.irishrail.ie). For more detailed advice on train travel options, visit www.ricksteves.com/rail.

If you opt for public transportation, you’ll probably spend more time on Irish buses than Irish trains. But be aware: Public transportation (especially cross-country Irish buses) will likely put your travels into slow motion.

For example, driving across County Kerry from Kenmare to Dingle takes two hours. If you go by bus, the same trip takes almost four hours. The trip by bus usually requires two transfers (in Killarney and Tralee, each involving a wait for the next bus), and the buses often take a rural milk-run route, making multiple stops along the way. But not every Irish coach trip will involve this kind of delay. They’re sometimes more direct than trains; for example, the bus from Dublin to Derry takes four hours with few stops, while the train takes six and requires a change. But in general buses tend to be slower than trains (by about a third), so if you opt to go by coach, be realistic about your itinerary and study the schedules ahead of time. The Bus Éireann Expressway Bus Timetable comes in handy (free, available at some bus stations or online at www.buseireann.ie, bus info toll tel. 1850-836-611).

Buses are much cheaper than trains. Round-trip bus tickets usually cost less than two one-way fares. For example, Tralee to Dingle is €14 one-way and €19 round-trip, and Kinsale to Cork is €9 one-way and €13 round-trip when purchased the day before. The Irish distinguish between “buses” (for in-city travel with lots of stops) and “coaches” (long-distance cross-country runs).

You may need to do some trips partly by train. For instance, if you’re going from Dublin to Dingle without a car, you’ll need to take a train to Tralee and catch a bus from there. Similarly, to go from Dublin to Kinsale without a car, take a train to Cork and then a bus; and from Dublin to Doolin, take a train to Galway or Ennis and then a bus.

If you’re traveling up and down Ireland’s west coast, buses are best (or a combination of buses and trains); relying on rail only here is too time-consuming. Note that some rural coach stops are by “request only.” This means the coach will drive right on by unless you flag it down by extending your arm straight out, with your palm open.

Bus stations are normally at or near train stations. On some Irish buses, sporting events are piped throughout the bus; have earplugs handy if you prefer a quieter ride.

Busy bus travelers can look into Bus Éireann’s Open Road tourist travel passes, which start at three days of travel in a six-day period and go up to as many as 15 days in a 30-day period. The passes can be pricey so make sure you add up your point-to-point journeys and compare to the pass prices once you know your itinerary (www.buseireann.ie, select “Tickets” and then “Tourist Travel Passes”). It can be a good option for those who are phobic about driving.

Some companies offer backpacker’s bus circuits. These hop-on, hop-off bus circuits take mostly youth hostelers around the country cheaply and easily, with the assumption that they’ll be sleeping in hostels along the way. For example, Paddy Wagon cuts Ireland in half and offers three- to nine-day “tours” of each half (north and south) that can be combined into one whole tour connecting Dublin, Cork, Killarney, Dingle, Galway, Westport, Donegal, Derry, and Belfast (May-Oct, 5 Beresford Palace, Dublin, tel. 01/823-0822, toll-free from UK tel. 0800-783-4191, www.paddywagontours.com). They also offer day tours to the Giant’s Causeway, Belfast, Cliffs of Moher, Glendalough, or Kilkenny.

Students can use their ISIC (student card, www.isic.org) to get discounts on cross-country coaches (up to 50 percent). Children 5-15 pay half-price on trains, and wee ones under age 5 go free.

Most Irish taxis are reliable and cheap. In many cities, couples can travel short distances by cab for little more than two bus or subway tickets. Taxis can be your best option for getting to the airport for an early morning flight or to connect two far-flung destinations. If you like ride-booking services like Uber, these apps usually work in Irish cities just like they do in the US: You request a car on your mobile device (connected to Wi-Fi or a data plan), and the fare is automatically charged to your credit card.

Travelers from North America are understandably hesitant when they consider driving in Ireland, where you must drive on the left side of the road. The Irish government statistics say that 10 percent of all car accidents on Irish soil involve a foreign tourist. But careful drivers—with the patient support of an alert navigator—usually get the hang of it by the end of the first day.