Isaiah

by David W. Baker

Sargon

Kim Walton, courtesy of the Oriental Institue Museum

Introduction

Isaiah’s magnificent prophecy spans not only history, going from creation (e.g., 42:5) to eternity (e.g., 9:7), but also geography, with an interest ranging between God’s own people through all of humanity (e.g., 2:2). Containing both words of hope and horror, its key theme is God himself, who is referred to hundreds of times.

Isaiah prophesies during the latter half of the eighth century B.C. during the reign of four named kings (1:1). His prophecies do not simply concern his own era, however, but anticipate both horrifying and hopeful events in Judah’s future. They describe a period of destruction and exile, with many of the people being deported far away from their own land, which will be ravaged and destroyed (586 B.C.). Some of Isaiah addresses the situation of exile (chs. 40–55). This is not the end, however, since the exiles will return and the land will be rebuilt (c. 535 B.C.); other sections of the book seem directed toward that situation (chs. 56–66).

Family of Judah being taken into exile from Lachish

Caryn Reeder, courtesy of the British Museum

The compositional history of Isaiah is debated, with numerous competing views as to the number of authors and the times of composition.2 This discussion is beyond the scope of the present study, but whichever view is espoused, the historical scope of the prophecy covers a period of over two centuries. Here we summarize the sweep of history between the eighth and fifth centuries B.C.

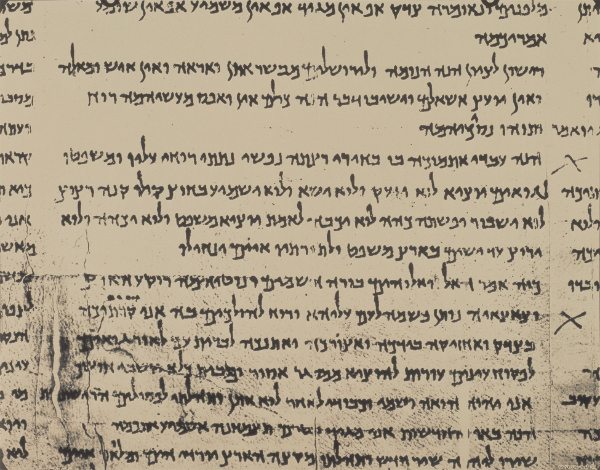

Manuscript of Isaiah from the Dead Sea Scrolls

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Israel Museum (IDAM)

In the beginning of this period, Israel was controlled by Assyria, a major world power whose capital, Nineveh (Mosul in contemporary Iraq), is on the Tigris River, but whose empire in this period stretched from what is now Iran as far west as Egypt. Lying in the midst of major land routes between Assyria and Egypt, Israel felt repeatedly the horrors of war and destruction.

Just prior to the time of Isaiah, a succession of three Assyrian kings arose who were weaker and less aggressive than their predecessors, so Israel and Judah enjoyed relative peace and prosperity. This came to an abrupt end in 745 B.C. when a new and powerful king gained the Assyrian throne. Tiglath-pileser III (744–727 B.C.; 2 Kings 15:29; cf. 15:19, where he is called Pul) reinvigorated Assyrian expansion and aggression until the end of the Assyrian empire late in the following century. The northern kingdom of Israel faced more imminent external pressure. Her king, Jeroboam II, had just died and his dynasty was brought to an end by the assassination of his son Zechariah (2 Kings 15:8–12), followed by a rapid turnover of rulers, likely influenced by the Assyrian pressure (v. 19).

| Judean Kings | |

|---|---|

|

Amaziah |

796–767 B.C. |

|

Uzziah (Azariah) |

(791)1–740/39 |

|

Jotham |

(750)–732/731 |

|

Ahaz |

(744/743)–716/715 |

|

Hezekiah |

716/715–687/686 |

|

Manasseh |

(696/695)–642/641 |

|

Amon |

642/641–640/639 |

|

Josiah |

640/639–609 |

|

Jehoahaz |

609 |

|

Jehoiakim |

609–597 |

|

Jehoiachin |

597 |

|

Zedekiah |

597–586 |

Uzziah, the king of Judah, also died (740 B.C.; Isa. 6:1), but his passing, though traumatic, was expected since he was suffering from an incapacitating skin disease and his son Jotham was effectively ruling in his place (2 Kings 15:5). Jotham’s reign was not seriously affected by Assyria directly, but, ironically, by an alliance between Judah’s sister nation, Israel under Pekah, with their northern neighbor Aram, under Rezin (15:37). These two allies wanted Judah to join their coalition against Assyria, though their actual motives are unstated; they were too small to oppose Assyria on their own.3

Judah refused to do join the coalition, leading to the confrontation known as the Syro-Ephraimite War (Isa. 6–7; 2 Kings 16:5–9; 2 Chr. 28:5–21), which affected especially Ahaz, Jotham’s son. He dithered back and forth on whether to side with Assyria, who was strong and brutal, or Israel and Aram, who were stronger than Judah and also close by. He finally opted for a pro-Assyrian policy, against the urgings of Isaiah (Isa. 7:7–9), and bribed Tiglath-pileser to leave him alone and instead deal with the opposing alliance, which the Assyrian king did in 734–732 (2 Kings 16:7–9).4

When Tiglath-pileser died in 727 B.C., his subjects, including Hoshea, king of Israel, asserted their independence. His son and heir, Shalmaneser V (726–722 B.C.), besieged Samaria, the Israelite capital (2 Kings 17:4), and exiled its leaders under Sargon II (721–705 B.C.; vv. 5–6). In one of his annals he records: “I besieged and conquered Samaria, led away booty 27,290 inhabitants of it . . . and imposed on them the tribute of the former king.”5 In the period immediately after Sargon’s death, while his son Sennacherib (704–681 B.C.) was occupied securing the throne, several of his vassals rebelled, requesting help from Ahaz’s son and successor, Hezekiah (2 Kings 18:14–16; 715–687 B.C.).

Assyria proved too strong for any such alliance, moving against it in 701 B.C., conquering many and extracting tribute from them. Even so, Hezekiah did not join a coalition against them spearheaded by Philistia in 715–713, which was short-lived, with the Philistine capital, Ashdod, destroyed (Isa. 14:28–31; 20:1–6).6 Sennacherib proved able and reestablished control over Babylon and then turned in his third campaign against Hezekiah and the west in 701.7 He captured much of Judah, but was unable to take either Hezekiah or Jerusalem, possibly holding off because of payment of tribute. Sennacherib does boast: “He himself, I locked up within Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage.”8 While the Bible records the siege (2 Kings 18:17–19:9), it records no defeat, saying rather that the Assyrian forces unexpectedly withdrew (vv. 35–36).

Tiglath-pileser III

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Judah still remained under Assyrian control, who continued to demand service from Manasseh, Hezekiah’s son and successor (687–642 B.C.; cf. 2 Chr. 33:11)9 as they were also battling in Egypt. Assyria started to weaken under the onslaught of their erstwhile vassals, the Scythians and the Medes, as well as the Babylonians, who expelled Assyria from their holdings in southern Mesopotamia in 625 B.C. under the leadership of Nabopolassar (626–605 B.C.).10 Allying with the Medes, he captured Assyria in 614 B.C., and the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, in 612 B.C. (Nahum; Zeph. 2:13–15). The seemingly overwhelming enemy was thus laid low, but not before great loss for Judah and the end of the nation of Israel.

Judah and Jerusalem

Manasseh remained under Assyrian subservience under Sennacherib’s able son, Esarhaddon (680–669). Since Egypt had been instrumental in fomenting repeated rebellions, Assyria turned her military attention toward her, going as far as destroying Thebes in 663 under the leadership of Ashurbanipal (668–627), Esarhaddon’s son.

Pressures continued to rise against Assyria, not only from Egypt and Babylon, but also from the Indo-Aryans from the north, including the Medes. Upon Ashurbanipal’s death, his successors were unable to maintain control, with Babylonia gaining self-rule in 626 under Nabopolassar. Joining with the Medes, Babylonia brought Assyria to its knees, destroying its capital, Nineveh, in 612 B.C. and destroying the Assyrian empire in 609.

During this period of weakness, Josiah (640–609 B.C.) won Judah’s independence and reestablished worship of Israel’s God. Josiah’s son, Jehoiakim, was an Egyptian vassal, but in 605 the Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar defeated the Egyptians at Carchemish. Jehoiakim change his allegiance, but he soon rebelled and died during a Babylonian siege, leaving a desperate situation for his son, Jehoiachin. At age eighteen, Jehoiachin was faced with an overwhelming force surrounding his city, which fell three months later, with the young king taken into exile.

Babylon then enthroned her own puppet king, Mattaniah (Jehoiachin’s uncle), renaming him Zedekiah, thus showing complete control over him. The prophet Jeremiah warned Zedekiah that any defiance of Babylon was futile, since God himself was turning against his own wayward people. The king did not listen, so after a two-year siege, Jerusalem fell in July, 586 B.C. The king was blinded and taken into exile along with many of the people; the temple and other important buildings were destroyed as were the very walls of the city, and Babylon placed Gedaliah, who was not even of royal birth, over Judah as governor. This looked like the end of God’s own people.

This was not the case, however, since the Neo-Babylonian empire was itself short-lived. After its strongest and longest ruling king, Nebuchadnezzar (605–562), died, three inferior monarchs reigned, but in the meantime a coalition was forming in the east between the Medes and the Persians. Under the able leadership of Cyrus, their armies moved in and brought the Neo-Babylonian empire to an end in 539 B.C. This had a direct impact on the Judean exiles since the Persians exercised a different foreign policy from either the Assyrians or Babylonians. The latter had taken leading citizens of captured nations into exile far away from their homes in order to lower the chances of their trying to liberate their country. Persia, by contrast, left conquered people in their homeland, or, in the case of Judah, allowed those who desired to return to their native land.

Not every Israelite in Babylonian exile took advantage of the opportunity to return to Judah (Ezra 2:64–65 numbers the returnees at 49,897). Life in Babylon and Persia was economically good for many, allowing some to reach high office (e.g., Esther) and live in relative comfort. The returnees to Judah found life difficult, facing hostile neighbors and a daunting rebuilding task. The latter chapters in Isaiah apparently offer encouragement to such returnees.