Jerusalem’s Covenant with Death (28:14–29)

Covenant with death, with the grave (28:15). See comment on 5:14. This is probably ironically metaphorical. Israel is trying to escape Assyria’s control through military alliances with the Canaanites, with their deity Mot (“death”729) or Molech (see 57:5), or with Egypt (30:1–7) and her god of death, Osiris.730 Politically, Israel is turning its back on Yahweh, the life-giving God, to submit to someone who not only worships death deities, but whose submission to them renders Israel’s own national existence dead. While these death deities are at the head of the pantheon of neither Canaan nor Egypt, their existence in their respective pantheons makes a useful hook on which Isaiah can hang his expressions of shock at the actions of residents of Jerusalem.

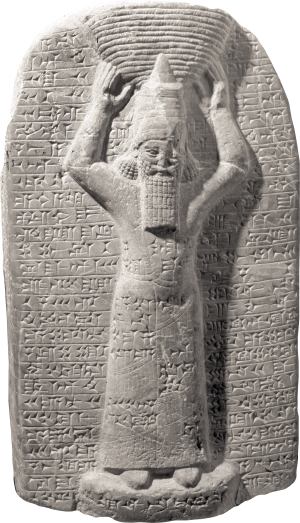

Cornerstone for a sure foundation (28:16). A building stands or falls based on the solidness of its foundation (see 44:28), and the cornerstone is what aligns and founds it. As the first stone laid, everything else needs to square to it. Laying the foundation also has important symbolism, and kings took part in a special ceremony. Esarhaddon wrote, for example: “In a favorable month, on a propitious day, on gold, silver . . . and wine I laid its foundation with limestone, hard stone of the mountains. . . . I made monuments and inscriptions with my name and laid them in it.”731

Assyrian king with basket on head carrying ceremonial first brick for temple building

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

In Mesopotamia, often foundation inscriptions were either inscribed on bricks or tablets buried in the foundation, dedicating the building to a deity or lauding the building king.732 Here it is Zion, residence of God and depository of his expectations for Israel, that is to align their national life and upon whose solidity they can depend.

Mount Perazim . . . Valley of Gibeon (28:21). David defeated the Philistines at Mount Perazim (2 Sam. 5:20) near Jerusalem. Its elevation provided a tactical advantage over the enemy moving in the valley below. Joshua successfully fought the Amorites at Gibeon, situated on a smaller hill above surrounding fields near Jerusalem, a site identified with el-Jib.733

Planting . . . plow . . . harrowing (28:24). Since agriculture was central to the existence of most people in this period, it is well represented in texts and pictures. Plowing late in the year loosened the soil to accept seed.734 Some crops were seeded by throwing (“broadcasting”; e.g., dill and cumin),735 while others were planted more carefully by seed drills, to keep each crop type separated. An Akkadian seal shows a wooden plow being pulled by two oxen.736

Plowing scenes on Egyptian relief

Manfred Näder, Gabana Studios, Germany

His God instructs him (28:26). Farming is here not something easily come by; rather it needs divine guidance. The Sumerians also had a “farmer’s almanac,” which, according to its colophon, was given by the farmer goddess Ninurta to help humans in this endeavor.737