I call this a digression for two reasons. First, the formulation of my anti-essentialism in the third paragraph of the present section is undoubtedly biased by hindsight. Secondly, because the later parts of the present section are devoted not so much to carrying on the story of my intellectual development (though this is not neglected) as to discussing an issue which it has taken me a lifetime to clarify.

I do not wish to suggest that the following formulation was in my mind when I was fifteen, yet I cannot now state better than in this way the attitude I reached in that discussion with my father which I mentioned in the previous section:

Never let yourself be goaded into taking seriously problems about words and their meanings. What must be taken seriously are questions of fact, and assertions about facts: theories and hypotheses; the problems they solve; and the problems they raise.

In the sequel I shall refer to this piece of self-advice as my anti-essentialist exhortation. Apart from the reference to theories and hypotheses which is likely to be of a much later date, this exhortation cannot be very far from an articulation of the feelings I harboured when I first became conscious of the trap set by worries or quarrels about words and their meanings. This, I still think, is the surest path to intellectual perdition: the abandonment of real problems for the sake of verbal problems.

However, my own thoughts on this issue were for a long time bedevilled by my naive yet confident belief that all this must be well known, especially to philosophers, provided they were sufficiently up to date. This belief led me later, when I began more seriously to read philosophical books, to try to identify my problem—the relative unimportance of words—with one of the standard problems of philosophy. Thus I decided that it was very closely related to the classical problem of universals. And although I realized fairly soon that my problem was not identical with that classical problem, I tried hard to see it as a variant of the classical problem. This was a mistake. But in consequence I became greatly interested in the problem of universals and its history; and I soon came to the conclusion that behind the classical problem of universal words and their meaning (or sense, or denotation) there loomed a deeper and more important problem: the problem of universal laws and their truth; that is, the problem of regularities.

The problem of universals is even today treated as if it were a problem of words or of language usages; or of similarities in situations, and how they are matched by similarities in our linguistic symbolism. It seemed to me quite obvious, however, that it was much more general; that it was fundamentally a problem of reacting similarly, to biologically similar situations. Since all (or almost all) reactions have, biologically, an anticipatory value, we are led to the problem of anticipation or expectation, and so to that of adaptation to regularities.

Now throughout my life I have not only believed in the existence of what philosophers call an “external world” but I have also regarded the opposite view as one not worth taking seriously. This does not mean that I never argued the issue with myself, or that I never experimented with, for example, “neutral monism” and similar idealistic positions. Yet I was always an adherent of realism; and this made me sensitive to the fact that within the context of the problem of universals this term “realism” was used in a quite different sense; that is, to denote positions opposed to nominalism. In order to avoid this somewhat misleading use I invented, when working on The Poverty of Historicism (probably in 1935, see the “Historical Note” to the book edition), the term “essentialism” as a name for any (classical) position which is opposed to nominalism, and especially for the theories of Plato and Aristotle (and, among the moderns, for Husserl’s “intuition of essences”).

At least ten years before I chose this name I had become aware of the fact that my own problem, as opposed to the classical problem of universals (and its biological variant), was a problem of method. After all, what I had originally impressed on my mind was an exhortation to think, to proceed, in one way rather than in another. This is why, long before I invented the terms “essentialism” and “anti-essentialism”, I had qualified the term “nominalism” by the term “methodological”, using the name “methodological nominalism” for the attitude characteristic of my exhortation. (I now think this name a little misleading. The choice of the word “nominalism” was the result of my attempt to identify my attitude with some well-known position, or at least to find similarities between it and some such position. Classical “nominalism”, however, was a position which I never accepted.)

In the early 1920s I had two discussions which had some influence on these ideas. The first was a discussion with Karl Polanyi, the economist and political theorist. Polanyi thought that what I described as “methodological nominalism” was characteristic of the natural sciences but not of the social sciences. The second discussion, somewhat later, was with Heinrich Gomperz, a thinker of great originality and immense erudition, who shocked me by describing my position as “realist” in both senses of the word.

I now believe that Polanyi and Gomperz were both right. Polanyi was right because the natural sciences are largely free from verbal discussion, while verbalism was, and still is, rampant in many forms in the social sciences. But there is more to it. I should now say7a that social relations belong, in many ways, to what I have more recently called “the third world” or better “world 3”, the world of theories, of books, of ideas, of problems; a world which, ever since Plato—who saw it as a world of concepts—has been studied mainly by essentialists. Gomperz was right because a realist who believes in an “external world” necessarily believes in the existence of a cosmos rather than a chaos; that is, in regularities. And though I felt more opposed to classical essentialism than to nominalism, I did not then realize that, in substituting the problem of biological adaptation to regularities for the problem of the existence of similarities, I stood closer to “realism” than to nominalism.

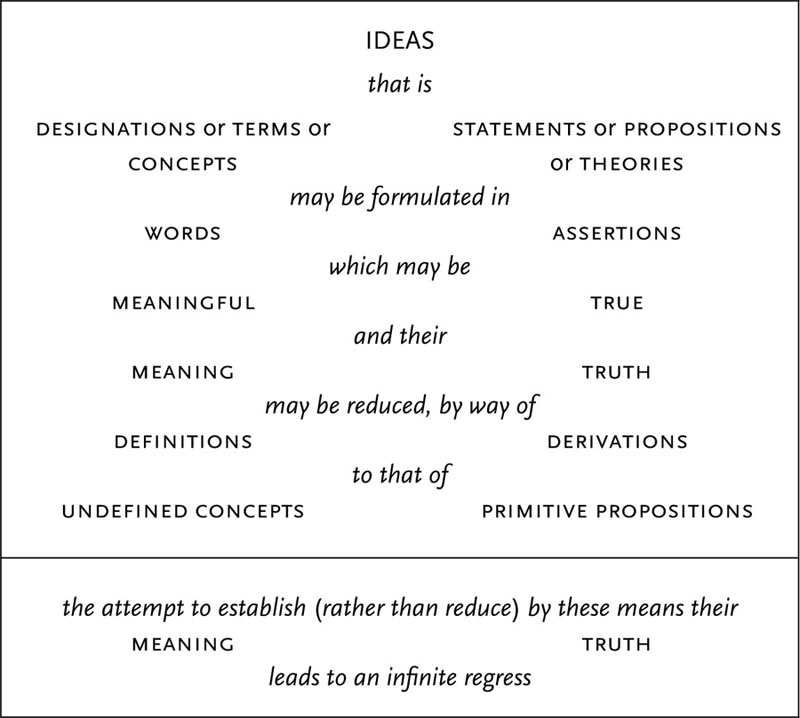

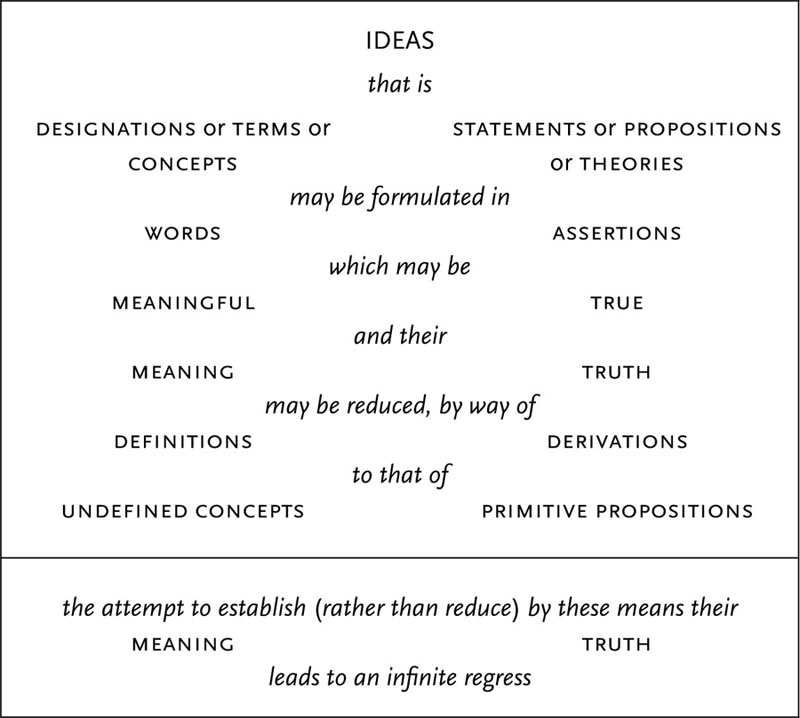

In order to explain these matters as I see them at present, I will make use of a table of ideas which I first published in “On the Sources of Knowledge and of Ignorance”.8

This table is in itself quite trivial: the logical analogy between the left and right sides is well established. However, it can be used to bring home my exhortation, which may now be reformulated as follows.

In spite of the perfect logical analogy between the left and the right sides of this table, the left-hand side is philosophically unimportant, while the right-hand side is philosophically all-important.9

This implies the view that meaning philosophies and language philosophies (so far as they are concerned with words) are on the wrong track. In matters of the intellect, the only things worth striving for are true theories, or theories which come near to the truth—at any rate nearer than some other (competing) theory, for example an older one.

This, I suppose, most people will admit; but they will be inclined to argue as follows. Whether a theory is true, or new, or intellectually significant, depends on its meaning; and the meaning of a theory (provided it is grammatically unambiguously formulated) is a function of the meanings of the words in which the theory is formulated. (Here, as in mathematics, a “function” is intended to take account of the order of the arguments.)

This view of the meaning of a theory seems almost obvious; it is widely held, and often unconsciously taken for granted.10 Nevertheless, there is hardly any truth in it. I would counter it with the following rough formulation.

The relationship between a theory (or a statement) and the words used in its formulation is in several ways analogous to that between written words and the letters used in writing them down.

Obviously the letters have no “meaning” in the sense in which the words have “meaning”; although we must know the letters (that is, their “meaning” in some other sense) if we are to recognize the words, and so discern their meaning. Approximately the same may be said about words and statements or theories.

Letters play a merely technical or pragmatic role in the formulation of words. In my opinion, words also play a merely technical or pragmatic role in the formulation of theories. Thus both letters and words are mere means to ends (different ends). And the only intellectually important ends are: the formulation of problems; the tentative proposing of theories to solve them; and the critical discussion of the competing theories. The critical discussion assesses the submitted theories in terms of their rational or intellectual value as solutions to the problem under consideration; and as regards their truth, or nearness to truth. Truth is the main regulative principle in the criticism of theories; their power to raise new problems and to solve them is another. (See my Conjectures and Refutations, .)

There are some excellent examples showing that two theories, T1 and T2, which are formulated in entirely different terms (terms which are not one-to-one translatable) may nevertheless be logically equivalent, so that we may say that T1 and T2 are merely different formulations of one and the same theory. This shows that it is a mistake to look on the logical “meaning” of a theory as a function of the “meanings” of the words. (In order to establish the equivalence of T1 and T2 it may be necessary to construct a richer theory T3 into which both T1 and T2 can be translated. Examples are various axiomatizations of projective geometry; and also the particle and the wave formalisms of quantum mechanics, whose equivalence can be established by translating them both into an operator language.)11

Of course, it is quite obvious that a change of one word can radically change the meaning of a statement; just as a change of one letter can radically change the meaning of a word, and with it, of a theory—as anybody interested in the interpretation of, say, Parmenides, will realize. Yet the mistakes of copyists or printers, though they may be fatally misleading, can more often than not be corrected by reflecting on the context.

Everybody who has done some translating, and who has thought about it, knows that there is no such thing as a grammatically correct and also almost literal translation of any interesting text. Every good translation is an interpretation of the original text; and I would even go so far as to say that every good translation of a nontrivial text must be a theoretical reconstruction. Thus it will even incorporate bits of a commentary. Every good translation must be, at the same time, close and free. Incidentally, it is a mistake to think that in an attempt to translate a piece of purely theoretical writing, aesthetic considerations are not important. One need only think of a theory like Newton’s or Einstein’s to see that a translation which gives the content of a theory but fails to bring out certain internal symmetries may be quite unsatisfactory; so much so that if somebody were given only this translation he would, if he discovered those symmetries, rightly feel he had himself made an original contribution, that he had discovered a theorem, even if the theorem was interesting chiefly for aesthetic reasons. (Somewhat similarly, a verse translation of Xenophanes, Parmenides, Empedocles, or Lucretius, is, other things being equal, preferable to a prose translation.)12

In any case, although a translation may be bad because it is not sufficiently precise, a precise translation of a difficult text simply does not exist. And if the two languages have a different structure, some theories may be almost untranslatable (as Benjamin Lee Whorf has shown so beautifully12a). Of course, if the languages are as closely related as, say, Latin and Greek, the introduction of a few newly coined words may suffice to make a translation possible. But in other cases an elaborate commentary may have to take the place of a translation.13

In view of all this, the idea of a precise language, or of precision in language, seems to be altogether misconceived. If we were to enter “Precision” in the Table of ideas (see above), it would stand on the left-hand side (because the linguistic precision of a statement would indeed depend entirely on the precision of the words used); its analogue on the right-hand side might be “Certainty”. I did not enter these two ideas, however, because my table is so constructed that the ideas on the right-hand side are all valuable; yet both precision and certainty are false ideals. They are impossible to attain, and therefore dangerously misleading if they are uncritically accepted as guides. The quest for precision is analogous to the quest for certainty, and both should be abandoned.

I do not suggest, of course, that an increase in the precision of, say, a prediction, or even a formulation, may not sometimes be highly desirable. What I do suggest is that it is always undesirable to make an effort to increase precision for its own sake—especially linguistic precision—since this usually leads to loss of clarity, and to a waste of time and effort on preliminaries which often turn out to be useless, because they are bypassed by the real advance of the subject: one should never try to be more precise than the problem situation demands.

I might perhaps state my position as follows. Every increase in clarity is of intellectual value in itself; an increase in precision or exactness has only a pragmatic value as a means to some definite end—where the end is usually an increase in testability or criticizability demanded by the problem situation (which for example may demand that we distinguish between two competing theories which lead to predictions that can be distinguished only if we increase the precision of our measurements).14

It will be clear that these views differ greatly from those implicitly held by many contemporary philosophers of science. Their attitude towards precision dates, I think, from the days when mathematics and physics were regarded as the Exact Sciences. Scientists, and also scientifically inclined philosophers, were greatly impressed. They felt it to be almost a duty to live up to, or to emulate, this “exactness”, perhaps hoping that fertility would emerge from exactness as a kind of by-product. But fertility is the result not of exactness but of seeing new problems where none have been seen before, and of finding new ways of solving them.

However, I will postpone my remarks on the history of contemporary philosophy to the end of this digression, and turn again to the question of the meaning or significance of a statement or a theory.

Having in mind my own exhortation never to quarrel about words, I am very ready to admit (with a shrug, as it were) that there may be meanings of the word “meaning” such that the meaning of a theory depends entirely on that of the words used in a very explicit formulation of the theory. (Perhaps Frege’s “sense” is one of them, though much that he says speaks against this.) Nor do I deny that, as a rule, we must understand the words in order to understand a theory (although this is by no means true in general, as the existence of implicit definition suggests). But what makes a theory interesting or significant—what we try to understand, if we wish to understand a theory—is something different. To put the idea first in a way which is merely intuitive, and perhaps a bit woolly, it is its logical relation to the prevailing problem situation which makes a theory interesting: its relation to preceding and competing theories: its power to solve existing problems, and to suggest new ones. In other words, the meaning or significance of a theory in this sense depends on very comprehensive contexts, although of course the significance of these contexts in their turn depends on the various theories, problems, and problem situations of which they are composed.

It is interesting that this apparently vague (and one might say “holistic”) idea of the significance of a theory can be analysed and clarified to a considerable extent in purely logical terms—with the help of the idea of the content of a statement or a theory.

There are in use, in the main, two intuitively very different but logically almost identical ideas of content, which I have sometimes called “logical content” and “informative content”; a special case of the latter I have also called “empirical content”.

The logical content of a statement or theory may be identified with what Tarski has called its “consequence class”; that is, the class of all the (nontautological) consequences which can be derived from the statement of theory.

For the informative content (as I have called it) we must consider the intuitive idea that statements or theories tell us the more “the more they prohibit” or exclude.15 This intuitive idea leads to a definition of informative content which, to some people, has seemed absurd: the informative content of a theory is the set of statements which are incompatible with the theory.16

It may be seen at once, however, that the elements of this set and the elements of the logical content stand in a one-one correspondence: to every element which is in one of the sets, there is in the other set a corresponding element, namely its negation.

We therefore find that whenever the logical strength, or the power, or the amount of information in a theory increases or decreases, its logical content and its informative content must both likewise increase or decrease. This shows that the two ideas are very similar: there is a one-one correspondence between what can be said about the one, and what can be said about the other. This shows that my definition of informative content is not entirely absurd.

But there are also differences. For example, for the logical content the following rule of transitivity holds: if b is an element of the content of a, and c an element of the content of b, then c is also an element of the content of a. Although there of course exists a corresponding rule for informative content, it is not a simple transitivity rule like this.17

Moreover, the content of any (nontautological) statement—say a theory t—is infinite. For let there be an infinite list of statements a, b, c,…, which are pairwise contradictory, and which individually do not entail t. (For most t’s, something like a: “the number of planets is 0”, b: “the number of planets is 1”, and so on, would be adequate.) Then the statement “t or a or both” is deducible from t, and therefore belongs to the logical content of t; and the same holds for b and any other statement in the list. From our assumptions about a, b, c,…, it can now be shown simply that no pair of statements of the sequence “t or a or both”, “t or b or both”,…, are interdeducible; that is, none of these statements entails any other. Thus the logical content of t must be infinite.

This elementary result concerning the logical content of any nontautological theory is of course well known. The argument is trivial since it is based on a trivial operation with the logical (nonexclusive) “or”;18 and so one may doubt, perhaps, whether the infinity of the content is not altogether a trivial affair, depending merely on those statements like “t or a or both” which are the results of a trivial method of weakening t. However, in terms of informative content it immediately becomes clear that the matter is not quite as trivial as it looks.

For let the theory under consideration be Newton’s theory of gravitation; call it N. Then any statement or any theory which is incompatible with N will belong to the informative content of N. Let us call Einstein’s theory of gravitation E. Since the two theories are incompatible, each belongs to the informative content of the other; each excludes, or forbids, or prohibits the other.

This shows in a very intuitive way that the informative content of a theory t is infinite in a far from trivial way: any theory which is incompatible with t, and thus any future theory which one day may supersede t (say, after some crucial experiment has decided against t) obviously belongs to the informative content of t. But just as obviously, we cannot know, or construct, these theories in advance: Newton could not foresee Einstein or Einstein’s successors.

Of course, it is now easy to find a precisely similar, though slightly less intuitive, situation concerning the logical content: since E belongs to the informative content of N, non-E belongs to the logical content of N: non-E is entailed by N, a fact which, obviously, could also not have been known to Newton, or anybody else, before E was discovered.

I have in lectures often described this interesting situation by saying: we never know what we are talking about. For when we propose a theory, or try to understand a theory, we also propose, or try to understand, its logical implications; that is, all those statements which follow from it. But this, as we have just seen, is a hopeless task: there is an infinity of unforeseeable nontrivial statements belonging to the informative content of any theory, and an exactly corresponding infinity of statements belonging to its logical content. We can therefore never know or understand all the implications of any theory, or its full significance.

This, I think, is a surprising result as far as it concerns logical content; though for informative content it turns out to be rather natural. (I have only once seen it stated in print,19 although I have referred to it in lectures for many years.) It shows, among other things, that understanding a theory is always an infinite task, and that theories can in principle be understood better and better. It also shows that, if we wish to understand a theory better, what we have to do first is to discover its logical relation to those existing problems and existing theories which constitute what we may call the “problem situation” at the particular moment of time.

Admittedly, we also try to look ahead: we try to discover new problems raised by our theory. But the task is infinite, and can never be completed.

Thus it turns out that the formulation which I have said earlier was “merely intuitive, and perhaps a bit woolly” can now be clarified. The nontrivial infinity of a theory’s content, as I have described it here, turns the significance of the theory into a partly logical and partly historical matter. The latter depends on what has been discovered, at a certain time, in the light of the prevailing problem situation, about the theory’s content; it is, as it were, a projection of this historical problem situation upon the logical content of the theory.20

To sum up, there is at least one meaning of the “meaning” (or “significance”) of a theory which makes it dependent upon its content and thus more dependent on its relations with other theories than on the meaning of any set of words.

These, I think, are some of the more important results which, during a lifetime, emerged from my anti-essentialist exhortation—which, in its turn, was the result of the discussion described in section 6. One further result is, quite simply, the realization that the quest for precision, in words or concepts or meanings, is a wild-goose chase. There simply is no such thing as a precise concept (say, in Frege’s sense), though concepts like “price of this kettle” and “thirty pence” are usually precise enough for the problem context in which they are used. (But note the fact that “thirty pence” is, as a social or economic concept, highly variable: it had a different significance a few years ago from what it has today.)

Frege’s opinion is different; for he writes: “A definition of a concept … must determine unambiguously of any object whether or not it falls under the concept … Using a metaphor, we may say: the concept must have a sharp boundary.”21 But it is clear that for this kind of absolute precision to be demanded of a defined concept, it must first be demanded of the defining concepts, and ultimately of our undefined, or primitive, terms. Yet this is impossible. For either our undefined or primitive terms have a traditional meaning (which is never very precise) or they are introduced by so-called “implicit definitions”—that is, through the way they are used in the context of a theory. This last way of introducing them—if they have to be “introduced”—seems to be the best. But it makes the meaning of the concepts depend on that of the theory, and most theories can be interpreted in more than one way. As a result, implicity defined concepts, and thus all concepts which are defined explicitly with their help, become not merely “vague” but systematically ambiguous. And the various systematically ambiguous interpretations (such as the points and straight lines of projective geometry) may be completely distinct.

This should be sufficient to establish the fact that “unambiguous” concepts, or concepts with “sharp boundary lines”, do not exist. Thus we need not be surprised at a remark like that by Clifford A. Truesdell about the laws of thermodynamics: “Every physicist knows exactly what the first and the second law mean, but … no two physicists agree about them.”22

We know now that the choice of undefined terms is largely arbitrary, as is the choice of the axioms of a theory. Frege was, I think, mistaken on this point, at least in 1892: he believed that there were terms which were intrinsically undefinable because “what is logically simple cannot have a proper definition”.23 However, what he thought of as an example of a simple concept—the concept of “concept”—turned out to be quite unlike what he thought it was. It has since developed into that of “set”, and few would now call it either unambiguous or simple.

At any rate, the wild-goose chase (I mean the interest in the left-hand side of the Table of Ideas) did go on. When I wrote my Logik der Forschung I thought that the quest for the meanings of words was about to end. I was an optimist: it was gaining momentum.24 The task of philosophy was more and more widely described as concerned with meaning, and this meant, mainly, the meanings of words. And nobody seriously questioned the implicity accepted dogma that the meaning of a statement, at least in its most explicit and unambiguous formulation, depends on (or is a function of) that of its words. This is true equally of the British language analysts and of those who follow Carnap in upholding the view that the task of philosophy is the “explication of concepts”, that is, making concepts precise. Yet there simply is no such thing as an “explication”, or an “explicated” or “precise” concept.

However, the problem still remains: what should we do in order to make our meaning clearer, if greater clarity is needed, or to make it more precise, if greater precision is needed? In the light of my exhortation the main answer to this question is: any move to increase clarity or precision must be ad hoc or “piecemeal”. If because of lack of clarity a misunderstanding arises, do not try to lay new and more solid foundations on which to build a more precise “conceptual framework”, but reformulate your formulations ad hoc, with a view to avoiding those misunderstandings which have arisen or which you can foresee. And always remember that it is impossible to speak in such a way that you cannot be misunderstood: there will always be some who misunderstand you. If greater precision is needed, it is needed because the problem to be solved demands it. Simply try your best to solve your problems and do not try in advance to make your concepts or formulations more precise in the fond hope that this will provide you with an arsenal for future use in tackling problems which have not yet arisen. They may never arise; the evolution of the theory may bypass all your efforts. The intellectual weapons which will be needed at a later date may be very different from those which anyone has in store. For example, it is almost certain that nobody trying to make the concept of simultaneity more precise would, before the discovery of Einstein’s problem (the asymmetries in the electrodynamics of moving bodies), have hit on Einstein’s “analysis”. (It should not be thought that I subscribe to the still popular view that Einstein’s achievement was one of “operational analysis”. It was not. See page 20 of my Open Society, [1957(h)]* and later editions, Volume II.)

The ad hoc method of dealing with problems of clarity or precision as the need arises might be called “dialysis”, in order to distinguish it from analysis: from the idea that language analysis as such may solve problems, or create an armoury for future use. Dialysis cannot solve problems. It cannot do so any more than definition or explication or language analysis can: problems can only be solved with the help of new ideas. But our problems may sometimes demand that we make new distinctions—ad hoc, for the purpose in hand.

This long digression25 has led me away from my main story, to which I will now return.

* References in square brackets such as [1957(h)] are to the Select Bibliography, pp. 283–98.