The siege of Antioch rapidly assumed legendary status in the experience of the participants and then in the memory of Christendom. From late October 1097 until early June 1098 the crusaders, never enough to surround the city completely, laboured unsuccessfully to starve or coerce Antioch, the key to northern Syria, into surrender. Two significant relief forces were repulsed: the first, led by Duqaq of Damascus, in late December with difficulty; the second, under Duqaq’s estranged brother Ridwan of Aleppo, with surprising conclusiveness at the battle of Lake Antioch early in February. The lack of unity among the squabbling Turkish warlords of Syria and the Jazira almost certainly saved the western host from annihilation, despite a now steady stream of reinforcements arriving from the west mainly by sea at the ports of Antioch, Latakiah and St Simeon.

Such were the constant anxieties and privations, notably a persistent shortage of food, that many tried to desert, including, abortively, Peter the Hermit in January 1098. However, force of hostile circumstance and mounting casualties acted as much to unite as to undermine. A common fund was created to pay for the construction of forts; the high command began habitually to co-operate in military operations. By the end of March the leadership had appointed Stephen of Blois as some sort of co-ordinator of their activities (ductor).

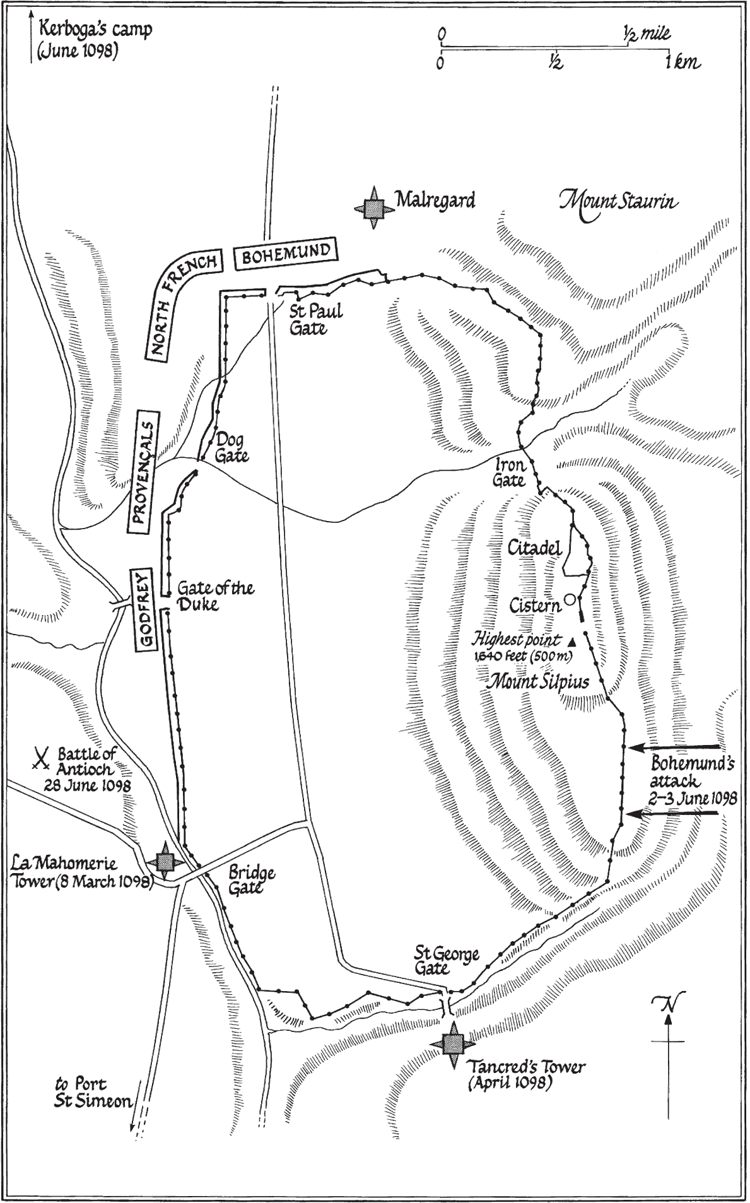

However, at some point Taticius, the Greek general assigned by Alexius I to accompany the crusade, departed, possibly to gather aid although later western opinion accused him of cowardice and treachery. More alarming were the reports in late May of the approach of a third and larger relieving army under Kerboga of Mosul which, although vitally held up for a few weeks at Edessa, threatened to catch the Christian host in the open, pinned between a Muslim field army and an unconquered garrison in Antioch. Unsurprisingly, panic spread. On 2 June a bout of hysteria hit the crusaders’ camp with many fleeing for the coast, including Stephen of Blois, who never entirely lived down the shame. Yet that very night (2–3 June), aided by an inside contact, Bohemund led a spectacular commando raid that gave the crusaders entry into the city, although the Muslim garrison still held out in the citadel high above the city. Antioch had been taken not a moment too soon: within hours the outriders of Kerboga’s massive army began to appear around the walls of the city. It must have seemed to the soldiers of the Cross that they had been saved by a miracle; to survive they were to need a few more.

In the month of October the Franks came to Antioch in Syria, a city founded by Seleucus, son of Antiochus. Seleucus made it his capital. It was previously called Reblata. Moreover it lay on the other side of the river which they called the Orontes. Our tents were ordered pitched before the city between it and the first milestone. Here afterwards battles were very frequently fought which were most destructive to both sides. When the Turks rushed out from the city they killed many of our men, but when the tables were turned they grieved to find themselves beaten.

Antioch is certainly a very large city, well fortified and strongly situated. It could never be taken by enemies from without provided the inhabitants were supplied with food and were determined to defend it.* There is in Antioch a much-renowned church dedicated to the honour of Peter the apostle where he, raised to the episcopate, sat as bishop after he had received from the Lord Jesus the primacy of the Church and the keys to the kingdom of heaven.

There is another church too, circular in form, built in honour of the blessed Mary, together with others fittingly constructed. These had for a long time been under the control of the Turks, but God, foreseeing all, kept them intact for us so that one day he would be honoured in them by ourselves.

The sea is, I think, about thirteen miles from Antioch. Because the Orontes river flows into the sea at that point, ships filled with goods from distant lands are brought up its channel as far as Antioch. Thus supplied with goods by sea and land, the city abounds with wealth of all kinds.

Our princes, when they saw how hard it would be to take the city, swore mutually to co-operate in a siege until, God willing, they took it by force or stratagem. They found a number of boats in the aforesaid river. These they took and fashioned into a pontoon bridge over which they crossed to carry out their plans. Previously they had been unable to ford the river.

But the Turks, when they had looked about anxiously and saw that they were beset by such a multitude of Christians, feared that they could not possibly escape them. After they had consulted together, Aoxianus, the prince and amir of Antioch, sent his son Sanxado to the sultan, that is the emperor of Persia, urging that he should aid them with all haste.* The reason was that they had no hope of other help except from Muhammad their advocate. Sanxado in great haste carried out the mission assigned to him.

Those who remained within the city guarded it, waiting for the assistance for which they had asked while they frequently concocted many kinds of dangerous schemes against the Franks. Nevertheless the latter foiled the stratagems of the enemy as well as they could.

On a certain day it happened that seven hundred Turks were killed by the Franks, and thus those who had prepared snares for the Franks were by snares overcome. For the power of God was manifest there. All of our men returned safely except one who was wounded by them.

Oh, how many Christians in the city, Greeks, Syrians and Armenians, did the Turks kill in rage and how many heads did they hurl over the walls with petrariae and fundibula [stone-throwing machines] in view of the Franks! This grieved our men very much. The Turks hated these Christians, for they feared that somehow the latter might assist the Franks against a Turkish attack.

After the Franks had besieged the city for some time and had scoured the country round about in search of food for themselves and were unable to find even bread to buy, they suffered great hunger. For this reason all were very much discouraged, and many secretly planned to withdraw from the siege and to flee by land or by sea.

But they had no money on which to live. They were even obliged to seek their sustenance far away and in great fear by separating themselves forty or fifty miles from the siege, and there in the mountains they were often killed by the Turks in ambush.

We felt that misfortunes had befallen the Franks because of their sins and that for this reason they were not able to take the city for so long a time. Luxury and avarice and pride and plunder had indeed vitiated them. Then the Franks, having again consulted together, expelled the women from the army, the married as well as the unmarried, lest perhaps defiled by the sordidness of riotous living they should displease the Lord. These women then sought shelter for themselves in neighbouring towns.*

The rich as well as the poor were wretched because of starvation as well as the slaughter, which daily occurred. Had not God, like a good pastor, held his sheep together, without doubt they would all have fled thence at once in spite of the fact that they had sworn to take the city. Many, though, because of the scarcity of food, sought for many days in neighbouring villages what was necessary for life; and they did not afterwards return to the army but abandoned the siege entirely.

At that time we saw a remarkable reddish glow in the sky and besides felt a great quake in the earth, which rendered us all fearful. In addition many saw a certain sign in the shape of a cross, whitish in colour, moving in a straight path towards the east.*

Thereafter as we approached Antioch, many princes proposed that we postpone the siege, especially since winter was close and the army, already weakened by summer heat, was now dispersed throughout strongholds.† They further argued that the crusaders should wait for imperial forces as well as for reported reinforcements en route from France, and so advised us to go into winter quarters until spring. Raymond, along with other princes standing in opposition, made a counter-proposal: ‘Through God’s inspiration we have arrived, through his loving kindness we won the highly fortified city, Nicaea, and through his compassion, have victory and safety from the Turks as well as peace and harmony in our army; therefore, our affairs should be entrusted to him. We ought not to fear kings or leaders of kings, and neither dread places nor times since the Lord has rescued us from many perils.’ The counsel of the latter prevailed and we arrived and encamped near Antioch so that the defenders firing from the heights of their towers wounded both our men in their tents and our horses.

We now take this opportunity to describe Antioch and its terrain so that our readers who have not seen it may follow the encounters and attacks. Nestled in the Lebanon mountains is a plain in width one day’s journey and in length one and a half day’s journey. The plain is bounded by a marsh; to the east a river which flows around a portion of this plain runs back to the edge of the mountains situated in the region to the south so that there is no crossing between the mountains and the river, and thence it winds its way to the nearby Mediterranean. Antioch is so located in these straits made by the stream cutting through the above-mentioned mountains that the western flow of the river past the lower wall forms the land between it and the city in the shape of an arrow. Actually the city, lying a bit to the east, rises high in that direction and within its enclosure embraces the tops of three mountains. The mountain situated to the north is so cut off from the others by a great cliff that only a most difficult approach is possible from one to another. The northern hill boasts a fortress and the middle hill another which in the Greek language is called Colax, but the third hill has only towers. Furthermore, this city extends two miles in length and is so protected with walls, towers and breastworks that it may dread neither the attack of machine nor the assault of man even if all mankind gathered to besiege it.

In short, the Frankish army of one hundred thousand armed men encamped along a line to the north of the described Antioch was content to remain there without making a frontal assault. Despite the fact that there were in the city only two thousand first-rate knights, four or five thousand ordinary knights and ten thousand or more footmen, Antioch was safe from attack as long as the gates were guarded because a valley and marshes shielded the high walls. Upon our arrival we took our positions helter-skelter, posted no watches, and acted so stupidly that the enemy, had they known, could have overrun any sector of our camp.

At this time regional castles and nearby cities fell to us largely because of fear of us and a desire to escape Turkish bondage. Our knights, ignoring public interest, left Antioch in the selfish hopes of acquiring some of these material benefits. Even those who stayed in camp enjoyed the high life so that they ate only the best cuts, rump and shoulders, scorned brisket and thought nothing of grain and wine.

In these good times only watchmen along the walls reminded us of our enemies concealed within Antioch, but the Turks soon discovered that the Christians openly and unarmed laid waste villages and fields. Although I am poorly informed of the Turkish movements, our foes shortly emerged from Antioch or came from Aleppo, some two days’ journey away, and killed our scattered and defenceless foragers. These countermeasures lessened our easy life, and the new opportunities for slaughter and pillage encouraged the Saracens to patrol their roads more consistently.

News of these events stirred the crusaders to pick Bohemund to lead a counter-attack. Although he could muster only 150 knights Bohemund, accompanied by the counts of Flanders and Normandy and prompted by shame of backing out of the venture, finally set out largely because of God’s admonition. They located, followed and drove the enemy to death in the Orontes.* Then the Christians returned happily with booty to the camp. At the same time Genoese ships docked on the coast at Port St Simeon some ten miles away.† During this time the enemy gradually slipped out of Antioch, killed squires and peasants who pastured their horses and cattle across the river, and returned with plunder into the city.

We now pause in our narrative to describe the setting so as to clarify coming events. Our tents stood close to the river and a pontoon bridge, made of boats found there, spanned it.‡ Antioch also had a bridge at the lower western corner and a hill opposite us upon which were two mosques and a chapel of tombs. In returning to our account we note again that our often outnumbered troops dared to tangle with the emboldened opposition. But the Turks, often dispersed and routed, renewed the fight partly because they were lightly armed with bows and were very agile on horseback, and partly because they could race back across their aforementioned bridge. They also liked to shower down arrows from their hill. I remind you that their bridge was almost a mile from ours, and on the plain between the bridges daily and incessant skirmishes took place. Because of their encampment near the banks of the river, Raymond and Adhemar bore the brunt of the raids. These hit-and-run attacks cost the above leaders all of their horses because the Turks, unskilled in the use of lances and swords, fought at a distance with arrows and so were dangerous in pursuit or flight.

In the third month of the siege when the count of Normandy was absent, Godfrey ill, and prices sky-high, Bohemund and the count of Flanders were selected to conduct a foraging expedition into Hispania while Raymond and Adhemar garrisoned the camp.* News of these developments caused the besieged to renew their usual sallies. In turn, Raymond moved against them in his customary way, put his footmen in battle order, and then accompanied by a few knights gave chase to the Turks. In the ensuing mêlée he captured and killed two of the assailants on the hill’s slope and drove the others across their bridge into Antioch. The sight was too much for the footmen, who broke ranks, dropped their standards, and ran pell-mell to the bridge. In their false security, they threw rocks and other missiles against the bridge defenders. The Turks regrouped and made a counterattack by the way of the bridge and a lower ford.

At this time our knights galloped towards our bridge in pursuit of a runaway horse made riderless by them. The footmen mistook this to be a flight of the knights and fled in a hurry from the Turkish charge. In the clash the Turks relentlessly butchered the fugitives. The Frankish knights, who stopped to fight, found themselves grabbed by the fleeing rabble, who snatched their arms, the manes and tails of their horses, and pulled them from their mounts. Other knights followed along in the push out of a sense of mercy and regard for the safety of their people. The Turks hurriedly and pitilessly chased and massacred the living and robbed the dead. It was not disgraceful enough for our men to throw down their weapons, to run away, to forget all sense of shame; no, they even jumped into the river to be hit by stones or arrows or to be drowned. Only the strong and skilful swimmers crossed the river and came to friendly quarters.

In the running fight from their bridge to our bridge, the Turks killed up to fifteen knights and around twenty footmen. The standard-bearer of the bishop of Le Puy and a noble young man, Bernard of Béziers, lost their lives there, and Adhemar’s standard was taken.* We hope that our account of the shamelessness of our army will bring neither blame nor anger of God’s servants against us, because really God on the one hand brought adulterous and pillaging crusaders to repentance and on the other cheered our army in Hispania [Ruj].

Gossip of the flourishing affairs and a sensational victory of Raymond’s troops spread from our camp to Bohemund, and as a result raised morale there. During an attack on a village Bohemund heard a few of his peasants take to heel and yell for help, and a force despatched to investigate the disorder soon saw a body of Turks and Arabs in hot pursuit. Among the auxiliary group were the count of Flanders and some Provençals, a name applied to all those from Burgundy, Auvergne, Gascony and Gothia [Guienne]. I call to your attention that all others in our army are called Franks, but the enemy make no distinction and use Franks for all. But I must return to the story. The count of Flanders rashly reined his horse against the Turks rather than suffer the disgrace of withdrawing to report the enemy’s approach. The Turks, unfamiliar with the use of swords in close battle, sought safety in flight, yet the count of Flanders did not lay down his sword until he had killed one hundred of his foes.

As the count of Flanders returned victoriously to Bohemund, he discovered twelve thousand Turks approaching his rearguard and he saw to his left a great number of footmen standing on a hill not far away. Following consultations with the rest of his army, he returned with reinforcements and took the offensive while Bohemund, with the other crusaders, trailed at some distance and thus shielded the rear lines. The Turks have a customary method of fighting, even when outnumbered, of attempting to surround their enemies; so in this encounter they did likewise, but the good judgement of Bohemund forestalled their tricks.*

The Turkish and Arabic attackers of the count of Flanders fled when they realised the ensuing fight would be waged hand to hand with swords rather than at a distance with arrows. The count of Flanders then pursued the foe for two miles and the living could see the slain lying all along the way like sheaves of grain in the field at harvest time. During this encounter Bohemund struck the ambushing forces, scattered and routed them, but could not prevent the previously mentioned mob of enemy footmen from sneaking away through places impassable on horseback.

I dare say, if I were not modest, I would rate this battle before the Maccabaean war, because Maccabaeus with three thousand struck down forty-eight thousand of his foes while here four hundred knights routed sixty thousand pagans. But we neither disparage the courage of Maccabaeus nor boast of the bravery of our knights; however, we proclaim God, once wonderful to Maccabaeus, was even more so to our army.

Our response to the attackers’ flight was such a diminution of bravery that the crusaders failed to follow the fleeing Turks. Our victorious army consequently came back to camp without provisions,† and the ensuing famine drove prices so high that 2 solidi scarcely had purchasing power equal to one day’s bread ration for one man, and other things were equally high. The poor along with the wealthy, who wished to save their goods, deserted the siege, and those who remained because of spiritual strength endured the sight of their horses wasting away from starvation. Straw was scarce and 7 or 8 solidi did not buy an adequate amount of grain for one night’s provender for one horse.

To add to our misfortunes, Bohemund, now famous for his brilliant service in Hispania, threatened to depart, adding that honour had brought him to his decision because he saw his men and horses dying from hunger; moreover, he stated that he was a man of limited means whose personal wealth was inadequate for a protracted siege. We learned afterwards that he made these statements because ambition drove him to covet Antioch.

In the mean time there was an earth tremor on the calends of January and we also saw a very miraculous sign in the sky.* On the night’s first watch a red sky in the north made it appear as if the sun rose on a new day. Although God had so scourged his army in order that we might turn to the light which arose in the darkness, yet the minds of certain ones were so dense and headstrong that they were recalled from neither riotous living nor plundering. Then Adhemar urged the people to fast three days, to pray, to give alms and to form a procession; he further ordered the priests to celebrate masses and the clerks to repeat psalms. Thus the blessed Lord, mindful of his loving kindness, delayed his children’s punishment lest it increase the pride of the pagans.

I turn now to one whom I had almost forgotten because he had been consigned to oblivion. This man, Taticius, accompanied our army in place of Alexius; he had a disfigured nose and lacked any redeeming qualities.† Daily, Taticius quietly admonished the princes to retire to nearby fortresses and drive out the besieged with numerous sallies and ambushes. But when all these things were disclosed to the count, who had been ill from the day of his forced flight near the bridge, he convened his princes and the bishop of Le Puy. Then at the conclusion of the council Raymond distributed 500 marks to the group on the terms that, if any one of the knights lost his horse, it would be replaced from the 500 marks and other funds which had been granted to the brotherhood.‡

This agreement of the brotherhood was very useful at that time because the poor people of the army, who wished to cross to the other side of the river to forage, dreaded the ceaseless attacks of the Turks; and few wished to fight them since the horses of the Provençals, scarcely numbering one hundred, were scrawny and feeble. I hasten to state that the same situation existed in the camp of Bohemund and other leaders.

Following the action of the brotherhood, our knights boldly attacked the enemy because those who had worthless and worn-out horses knew they could replace their lost steeds with better ones. Oh, yes! another fact may be added; all the princes with the exception of the count offered Antioch to Bohemund in the event that it was captured. So with this pact Bohemund and other princes took an oath that they would not abandon the siege of Antioch for seven years unless it fell sooner.*

While these affairs were conducted in camp, an unconfirmed story spread that the army of the emperor was approaching, an army composed, it was said, of many races, Slavs, Pechenegs, Cumans and Turcopoles.† Turcopoles were so named because they were either reared with Turks or were the offspring of a Christian mother and of a Turkish father. They feared to associate with us because of their bad treatment of us along the journey. Actually Taticius, that disfigured one, anxious for an excuse to run away, not only fabricated the above lie but added to his sins with perjury and betrayal of friends by hastening away in flight after ceding to Bohemund two or three cities, Tursol, Mamistra and Adana. Therefore, under the pretence of joining the army of Alexius, Taticius broke camp, abandoned his followers, and left with God’s curse; by this dastardly act, he brought eternal shame to himself and his men.‡

When we drew near to the bridge over the Orontes our scouts, who used always to go ahead of us, found barring their way a great number of Turks who were hurrying to reinforce Antioch, so they attacked the Turks with one heart and mind and defeated them. The barbarians were thrown into confusion and took to flight, leaving many dead in that battle, and our men who by God’s grace overcame them took much booty, horses, camels, mules and asses laden with corn and wine. Afterwards, when our main forces came up, they encamped on the bank of the river, and the gallant Bohemund came at once with four thousand knights to guard the city gate, so that no one could go out or come in secretly by night. Next day, Wednesday, 21 October, the main army reached Antioch about noon, and we established a strict blockade on three gates of the city, for we could not besiege it from the other side because a mountain, high and very steep, stood in our way.* Our enemies the Turks, who were inside the city, were so much afraid of us that none of them tried to attack our men for nearly a fortnight. Meanwhile we grew familiar with the surroundings of Antioch, and found there plenty of provisions, fruitful vineyards and pits full of stored corn, apple-trees laden with fruit and all sorts of other good things to eat.

The Armenians and Syrians who lived in the city came out and pretended to flee to us, and they were daily in our camp, but their wives were in the city. These men spied on us and on our power, and reported everything we said to those who were besieged in the city. After the Turks had found out about us, they began gradually to emerge and to attack our pilgrims wherever they could, not on one flank only but wherever they could lay ambush for us, either towards the sea or towards the mountain.

Not far off there stood a castle called Aregh, manned by many of the bravest of the Turks, who often used to make attacks on our men. When our leaders heard that such things were happening, they were very troubled and sent some of our knights to reconnoitre the place where the Turks had established themselves. When our knights, who were looking for the Turks, found the place where they used to hide, they attacked the enemy, but had to retreat a little way to where they knew Bohemund to be stationed with his army. Two of our men were killed there in the first attack. When Bohemund heard of this he went out, like a most valiant champion of Christ, and his men followed him. The barbarians fell upon our men because they were few, yet they joined battle in good order and many of our enemies were killed. Others, whom we captured, were led before the city gate and there beheaded, to grieve the Turks who were in the city.

There were others who used to come out of the city and climb upon a gate, whence they shot arrows at us, so that the arrows fell into my lord Bohemund’s camp, and a woman was killed by a wound from one of them.*

Thereafter all our leaders met together and summoned a council. They said, ‘Let us build a castle on top of Mount Mal-regard,† so that we can stay here safe and sound, without fear of the Turks.’ The castle was built and fortified, and all our leaders took turns in guarding it.

By and by, before Christmas, corn and all foodstuffs began to be very dear, for we dared not go far from the camp and we could find nothing to eat in the land of the Christians. (No one dared to go into the land of the Saracens except with a strong force.) Finally our leaders held a council to decide how they should provide for so many people, and in this council they determined that one part of our army should go and do its best to get supplies and to protect the flanks of our forces, while the other part should stay behind, faithfully to guard the non-combatants. Then Bohemund said, ‘Gentlemen and most gallant knights, if you wish, and if it seems to you a good plan, I will go on this expedition, with the count of Flanders.’ So when we had celebrated Christmas with great splendour these two set out on Monday the second day of the week,‡ and with them went others, more than twenty thousand knights and foot-soldiers in all, and they entered, safe and sound, into the land of the Saracens. Now it happened that many Turks, Arabs and Saracens had come together from Jerusalem and Damascus and Aleppo and other places* and were approaching to relieve Antioch, so when they heard that a Christian force had been led into their country they prepared at once for battle, and at daybreak they came to the place† where our men were assembled. The barbarians split up their forces into two bands, one before and one behind, for they wanted to surround us on all sides, but the noble count of Flanders, armed at all points with faith and with the sign of the Cross (which he bore loyally every day), made straight for the enemy with Bohemund at his side, and our men charged them in one line. The enemy straightway took to flight, turning tail in a hurry; many of them were killed and our men took their horses and other plunder. Others, who remained alive, fled quickly and went into ‘the wrath fitted for destruction’, but we came back in great triumph, and praised the glorified God the Three in One, who liveth and reigneth now and eternally. Amen.

While this was going on the Turks (enemies of God and holy Christendom) who were acting as garrison to the city of Antioch heard that my lord Bohemund and the count of Flanders were not with the besieging army, so they sallied from the city and came boldly to fight with our men, seeking out the places where the besiegers were weakest, for they knew that some very valiant knights were away, and they found that on the Tuesday‡ they could withstand us and do us harm. Those wretched barbarians came up craftily and made a sudden attack upon us, killing many knights and foot-soldiers who were off their guard. On that grievous day the bishop of Le Puy lost his seneschal, who was carrying his banner and guarding it, and if there had not been a river between us and them they would have attacked us more often and done very great harm to our people.

Just then the valiant Bohemund arrived with his army from the land of the Saracens, and he came over Tancred’s mountain* thinking that he might find something which could be carried off, for our men had pillaged all the land. Some of his followers had found plunder, but others were coming back empty-handed. Then the gallant Bohemund shouted at the fugitives from our camp, ‘You wretched and miserable creatures! You scum of all Christendom! Why do you want to run away so fast? Stop now, stop until we all join forces, and do not rush about like sheep without a shepherd. If our enemies find you rushing all over the place they will kill you, for they are on the watch day and night to catch you without a leader or alone, and they are always trying to kill you or to lead you into captivity.’ When he had said this he returned to his camp together with his men, but more of them were empty-handed than carrying plunder.

The Armenians and Syrians, seeing that our men had come back with scarcely any supplies, took counsel together and went over the mountains by paths which they knew, making careful enquiries and buying up corn and provisions which they brought to our camp, in which there was a terrible famine, and they used to sell an ass’s load for 8 hyperperi, which is 120 shillings in our money. Many of our people died there, not having the means to buy at so dear a rate.

Because of this great wretchedness and misery William the Carpenter and Peter the Hermit fled away secretly.† Tancred went after them and caught them and brought them back in disgrace. (They gave him a pledge and an oath that they were willing to return to the camp and give satisfaction to the leaders.) William spent the whole of the night in my lord Bohemund’s tent, lying on the ground like a piece of rubbish. The following morning, at daybreak, he came and stood before Bohemund, blushing for shame. Bohemund said to him, ‘You wretched disgrace to the whole Frankish army – you dishonourable blot on all the people of Gaul! You most loathsome of all men whom the earth has to bear, why did you run off in such a shameful way? I suppose that you wanted to betray these knights and the Christian camp, just as you betrayed those others in Spain?’* William kept quiet, and never a word proceeded out of his mouth. Nearly all the Franks assembled and humbly begged my lord Bohemund not to allow him to suffer a worse punishment. He granted their request without being angry, and said, ‘I will freely grant this for the love I bear you, provided that the man will swear, with his whole heart and mind, that he will never turn aside from the path to Jerusalem, whether for good or ill, and Tancred shall swear that he will neither do, nor permit his men to do, any harm to him.’ When Tancred heard these words he agreed, and Bohemund sent the Carpenter away forthwith; but afterwards he sneaked off without delay, for he was greatly ashamed.†

God granted that we should suffer this poverty and wretchedness because of our sins. In the whole camp you could not find a thousand knights who had managed to keep their horses in really good condition.

While all this was going on, our enemy Taticius,‡ hearing that the Turkish army had attacked us, admitted that he had been afraid that we had all perished and fallen into the hands of the enemy. So he told all sorts of lies, and said, ‘Gentlemen and most gallant knights, you see that we are here in great distress and that no reinforcements can reach us from any direction. Let me therefore go back to the country of Rum, and I will guarantee without delay to send by sea many ships, laden with corn, wine, barley, meat, flour, cheese and all sorts of provisions which we need; I will also have horses brought here to sell, and will cause goods to be brought hither by land under the emperor’s safe conduct. See, I will swear faithfully to do all this, and I will attend to it myself. Meanwhile my household and my pavilion shall stay in the camp as a firm pledge that I will come back as soon as I can.’

So that enemy of ours made an end of his speech. He left all his possessions in the camp; but he is a liar, and always will be. We were thus left in direst need, for the Turks were harrying us on every side, so that none of our men dared to go outside the encampment. The Turks were menacing us on the one hand, and hunger tormented us on the other, and there was no one to help us or bring us aid. The rank and file, with those who were very poor, fled to Cyprus or Rum or into the mountains. We dared not go down to the sea for fear of those brutes of Turks, and there was no road open to us anywhere.

Anna Comnena tried hard to counter western apologists’ exploitation of Taticius’ departure to vilify the Greeks by blaming it on a trick by Bohemund.

What happened then, you ask. Well, the Latins with the Roman army reached Antioch by what is called the ‘Quick Route’.* They ignored the country on either side. Near the walls of the city a ditch was dug, in which the baggage was deposited, and the siege of Antioch began. It lasted for three lunar months.† The Turks, anxious about the difficult position in which they found themselves, sent a message to the sultan of Khorasan,‡ asking him to supply enough men to help them defend the people of Antioch and chase away the besieging Latins. Now it chanced that a certain Armenian§ was on a tower of the city, watching that part of the wall allotted to Bohemund. This man often used to lean over the parapet and Bohemund, by flagrant cajolery and a series of attractive guarantees, persuaded him to hand over the city. The Armenian gave his word: ‘Whenever you like to give some secret sign from outside, I will at once hand over to you this small tower. Only make sure that you, and all the men under you, are ready. And have ladders, too, all prepared for use. Nor must you alone be ready: all the men should be in armour, so that as soon as the Turks see you on the tower and hear you shouting your war-cries, they may panic and flee.’ However, Bohemund for the time being kept this arrangement to himself. At this stage of affairs a man came with the news that a very large force of Agarenes was on the point of arriving from Khorasan; they would attack the Celts. They were under the command of Kerboga. Bohemund was informed and being unwilling to hand over Antioch to Taticius (as he was bound to do if he kept his oaths to the emperor) and coveting the city for himself, he devised an evil scheme for removing Taticius involuntarily.* He approached him. ‘I wish to reveal a secret to you’, he said, ‘because I am concerned for your safety. A very disturbing report has reached the ears of the counts – that the sultan has sent these men from Khorasan against us at the emperor’s bidding. The counts believe the story is true and they are plotting to kill you. Well, I have now done my part in forewarning you: the danger is imminent. The rest is up to you. You must consult your own interests and take thought for the lives of your men.’ Taticius had other worries apart from this: there was a severe famine (an ox-head was selling for 3 gold staters) and he despaired of taking Antioch. He left the place, therefore, boarded the Roman ships anchored in the harbour of Soudi [St Simeon] and sailed for Cyprus.

Muslim observers were no less transfixed by the epic struggle for Antioch. Abu Yala Hamza ibn Asad al-Tamimi (c.1073–1160), known, from his family’s name, as Ibn al-Qalanisi (‘son of the Hatter’), wrote a history of his native city, Damascus, for the years 974 to 1160. A prominent public official in Damascus, well educated and a poet as well as lawyer and administrator, Ibn al-Qalanisi supplies an exactly contemporary account of the irruption of the Franks into Syria written by someone who was already adult when the crusaders burst into Syria in the winter of 1097–8. Written before the fashion for an almost obligatory gloss of jihad rhetoric, Ibn al-Qalanisi’s description is generally factual and dispassionate without minimising the effect of the western invasion. Unlike many Muslim writers, who saw Syria as a peripheral backwater, Ibn al-Qalanisi is of interest because he is portraying his own region rather than attempting the more common Arabic literary exercise of a universal history.

In this year [1097] there began to arrive a succession of reports that the armies of the Franks had appeared from the direction of the sea of Constantinople with forces not to be reckoned for multitude. As these reports followed one upon the other, and spread from mouth to mouth far and wide, the people grew anxious and disturbed in mind. The king, Daud ibn Suleiman ibn Qutulmish,* whose dominions lay nearest to them, having received confirmation of these statements, set about collecting forces, raising levies and carrying out the obligation of Holy War. He also summoned as many of the Turkmens [Turkish freebooters] as he could to give him assistance and support against them, and a large number of them joined him along with the askar [military entourage] of his brother. His confidence having been strengthened thereby, and his offensive power rendered formidable, he marched out to the fords, tracks and roads by which the Franks must pass, and showed no mercy to all of them who fell into his hands. When he had thus killed a great number, they turned their forces against him, defeated him and scattered his army, killing many and taking many captive, and plundered and enslaved. The Turkmens, having lost most of their horses, took to flight. The king of the Greeks bought a great many of those whom they had enslaved, and had them transported to Constantinople. When the news was received of this shameful calamity to the cause of Islam, the anxiety of the people became acute and their fear and alarm increased. The date of this battle was 4 July 1097.*

At the end of July the amir Yaghi Sayan, lord of Antioch, accompanied by the amir Sukman ibn Ortuq† and the amir Kerboga, set out with his askar towards Antioch, on receipt of news that the Franks were approaching it. Yaghi Sayan therefore hastened to Antioch, and despatched his son to al-Malik Duqaq at Damascus, to Janah al-Dawla at Hims, and to all the other cities and districts, appealing for aid and support, and inciting them to hasten to the Holy War, while he set about fortifying Antioch and expelling its Christian population. On 12 September the Frankish armies descended on Baghras and developed their attack upon the territories of Antioch, whereupon those who were in the castles and forts adjacent to Antioch revolted and killed their garrisons except for a few who were able to escape from them. The people of Artah did likewise, and called for reinforcements from the Franks. During July–August a comet appeared in the west; it continued to rise for a space of about twenty days, and then disappeared.

Meanwhile, a large detachment of the Frankish army, numbering about thirty thousand men, had left the main body and set about ravaging the other districts, in the course of which they came to al-Bara, and slaughtered about fifty men there. Now the askar of Damascus had reached the neighbourhood of Shayzar, on their way to support Yaghi Sayan, and when this detachment made its descent on al-Bara, they moved out against it. After a succession of charges by each side, in which a number of their men were killed, the Franks returned to al-Ruj, and thence proceeded towards Antioch.‡ Oil, salt and other necessaries became dear and unprocurable in Antioch, but so much was smuggled into the city that they became cheap again. The Franks dug a trench between their position and the city, owing to the frequent sallies made against them by the army of Antioch.

Now the Franks, on their first appearance, had made a covenant with the king of the Greeks, and had promised him that they would deliver over to him the first city which they should capture. They then captured Nicaea, and it was the first place they captured, but they did not carry out their word to him on that occasion, and refused to deliver it up to him according to the stipulation.* Subsequently they captured on their way several frontier fortresses and passes.

The attitude in the Christian army, at once fearful yet optimistic of God’s favour, is captured in two letters written from the crusader camp outside Antioch early in 1098.

The patriarch of Jerusalem and the bishops, Greek as well as Latin, and the whole army of God and the Church to the Church of the west; fellowship in celestial Jerusalem, and a portion of the reward of their labour.

Since we are not unaware that you delight in the increase of the Church, and we believe that you are concerned to hear matters adverse as well as prosperous, we hereby notify you of the success of our undertaking. Therefore, be it known to your delight that God has triumphed in forty important cities and in two hundred fortresses of his Church in Romania [Asia Minor], as well as in Syria, and that we still have one hundred thousand men in armour, besides the common throng, though many were lost in the first battles. But what is this? What is one man in a thousand? Where we have a count, the enemy have forty kings; where we have a company, the enemy have a legion; where we have a knight, they have a duke; where we have a foot-soldier, they have a count; where we have a camp, they have a kingdom. However, confiding not in numbers, nor in bravery, nor in any presumption, but protected by justice and the shield of Christ, and with St George, Theodore, Demetrius and Basil, soldiers of Christ, truly supporting us, we have pierced, and in security are piercing, the ranks of the enemy. On five general battlefields, God conquering, we have conquered.

But what more? In behalf of God and ourselves, I, apostolic patriarch, the bishops and the whole order of the Lord, urgently pray, and our spiritual mother Church calls out: ‘Come, my most beloved sons, come to me, retake the crown from the hands of the sons of idolatry, who rise against me – the crown from the beginning of the world predestined for you.’ Come, therefore, we pray, to fight in the army of the Lord at the same place in which the Lord fought, in which Christ suffered for us, leaving to you an example that you should follow his footsteps. Did not God, innocent, die for us? Let us therefore also die, if it be our lot, not for him, but for ourselves, that by dying on earth we may live for God. Yet it is [now] not necessary that we should die, nor fight much, for we have [already] sustained the more serious trials, but the task of holding the fortresses and cities has been heavily reducing our army. Come, therefore, hasten to be repaid with the twofold reward – namely, the land of the living and the land flowing with milk and honey and abounding in all good things. Behold, men, by the shedding of our blood the way is open everywhere. Bring nothing with you except only what may be of use to us. Let only the men come; let the women, as yet, be left. From the home in which there are two, let one, the one more ready for battle, come. But those, especially, who have made the vow, [let them come]. Unless they come and discharge their vow, I, apostolic patriarch, the bishops and the whole order of the Orthodox, do excommunicate them and remove them utterly from the communion of the Church. And do you likewise, that they may not have burial among Christians, unless they are staying for suitable reasons. Come, and receive the twofold glory! This, therefore, also write.

To his reverend lord M., by God’s grace archbishop of Rheims, A. of Ribemont, his vassal and humble servant – greeting.

Inasmuch as you are our lord and as the kingdom of France is especially dependent upon your care, we tell to you, our father, the events which have happened to us and the condition of the army of the Lord. Yet, in the first place, although we are not ignorant that the disciple is not above his master, nor the servant above his lord, we advise and beseech you in the name of our Lord Jesus to consider what you are and what the duty of a priest and bishop is. Provide therefore for our land, so that the lords may keep peace among themselves, the vassals may in safety work on their property, and the ministers of Christ may serve the Lord, leading quiet and tranquil lives. I also pray you and the canons of the holy mother church of Rheims, my fathers and lords, to be mindful of us, not only of me and of those who are now sweating in the service of God, but also of the members of the army of the Lord who have fallen in arms or died in peace.

But passing over these things, let us return to what we promised. Accordingly after the army had reached Nicomedia, which is situated at the entrance to the land of the Turks, we all, lords and vassals, cleansed by confession, fortified ourselves by partaking of the body and blood of our Lord, and proceeding thence beset Nicaea on the second day before the nones of May.* After we had for some days besieged the city with many machines and various engines of war, the craft of the Turks, as often before, deceived us greatly. For on the very day on which they had promised that they would surrender, Suleiman† and all the Turks, collected from neighbouring and distant regions, suddenly fell upon us and attempted to capture our camp. However, the count of St Gilles, with the remaining Franks, made an attack upon them and killed an innumerable multitude. All the others fled in confusion. Our men, moreover, returning in victory and bearing many heads fixed upon pikes and spears, furnished a joyful spectacle for the people of God. This was on the seventeenth day before the calends of June.*

Beset moreover and routed in attacks by night and day, they surrendered unwillingly on the thirteenth day before the calends of July.† Then the Christians, entering the walls with their crosses and imperial standards, reconciled the city to God, and both within the city and outside the gates cried out in Greek and Latin, ‘Glory to thee, O God.’ Having accomplished this, the princes of the army met the emperor who had come to offer them his thanks, and having received from him gifts of inestimable value, some withdrew, with kindly feelings, others with different emotions.

We moved our camp from Nicaea on the fourth day before the calends of July‡ and proceeded on our journey for three days. On the fourth day the Turks, having collected their forces from all sides, again attacked the smaller portion of our army, killed many of our men and drove all the remainder back to their camps. Bohemund, count of the [Normans], Count Stephen [of Blois] and the count of Flanders commanded this section. When these were thus terrified by fear, the standards of the larger army suddenly appeared. Hugh the Great and the duke of Lorraine were riding at the head, the count of St Gilles and the venerable bishop of Le Puy followed. For they had heard of the battle and were hastening to our aid. The number of the Turks was estimated at 260,000. All of our army attacked them, killed many and routed the rest. On that day I returned from the emperor, to whom the princes had sent me on public business.

After that day our princes remained together and were not separated from one another. Therefore, in traversing the countries of Asia Minor and Armenia we found no obstacle, except that after passing Iconium, we, who formed the advance guard, saw a few Turks. After routing these, on the twelfth day before the calends of November,* we laid siege to Antioch, and now we captured the neighbouring places, the cities of Tarsus and Latakiah and many others, by force. On a certain day, moreover, before we besieged the city, at the ‘Iron Bridge’† we routed the Turks, who had set out to devastate the surrounding country, and we rescued many Christians.‡ Moreover, we led back the horses and camels with very great booty.

While we were besieging the city, the Turks from the nearest redoubt daily killed those entering and leaving the army. The princes of our army, seeing this, killed four hundred of the Turks who were lying in wait, drove others into a certain river and led back some as captives. You may be assured that we are now besieging Antioch with all diligence, and hope soon to capture it. The city is supplied to an incredible extent with grain, wine, oil and all kinds of food.

I ask, moreover, that you and all whom this letter reaches pray for us and for our departed brethren. Those who have fallen in battle are: at Nicaea, Baldwin of Ghent, Baldwin Chalderuns, who was the first to make an attack upon the Turks and who fell in battle on the calends of July,§ Robert of Paris, Lisiard of Flanders, Hilduin of Mazingarbe, Anseau of Caien, Manasses of Clermont, Laudunensis.

Those who died from sickness: at Nicaea, Guy of Vitreio, Odo of Vernolio [Verneuil (?)], Hugh of Rheims; at the fortress of Sparnum, the venerable abbot Roger, my chaplain; at Antioch, Alard of Spiniaeco, Hugh of Calniaco.

Again and again I beseech you, readers of this letter, to pray for us, and you, my lord archbishop, to order this to be done by your bishops. And know for certain that we have captured for the Lord two hundred cities and fortresses. May our mother, the western Church, rejoice that she has begotten such men, who are acquiring for her so glorious a name and who are so wonderfully aiding the eastern Church. And in order that you may believe this, know that you have sent to me a tapestry by Raymond ‘de Castello’. Farewell.

The siege continued with little sign of an immediate end.

News now came that the commander of the caliph at the head of a large army from Khorasan was bringing aid to Antioch.* Following a council of war in Adhemar’s house, footmen were ordered to defend the camp and knights to ride out against the new force. This decision came because it was likely that the unfit and timid ones in the ranks of the footmen would show more cowardice than bravery if they saw a large force of Turks. The expeditionary group left under the cover of night and hid in some hills two leagues away from camp so that the defenders could not send word of their departure. Now I beseech those who have attempted to disparage our army in the past to hear this; indeed may they hear so that when they understand God’s example of mercy on our behalf, they may hasten to give satisfaction with penitential wailing.

God increased the size of the six units of the knights so that each one seemed to grow from scarcely seven hundred men to more than two thousand. Certainly, it taxes me to know what to say of the bravado of the army whose knights actually sang warlike songs so joyously that they seemed to look upon the approaching battle as if it were a sport. It is to be observed here that the site of the coming fight was near the place where the river flowed within a mile of the marsh and thereby prohibited the Turkish customary encircling movements which depended upon the dispersion of their forces. Furthermore, God, who had offered the above-mentioned advantages, now offered us six adjoining valleys by which our troops could move to battle; consequently, within one hour we had marched out and occupied the field. Thus as the sun shone brightly on our arms and bucklers, the battle began with our men at first gradually pushing forward while the Turks ran to and fro, shot their arrows, and slowly retreated.*

Nevertheless, our troops suffered heavy losses until the first line of the Turks was driven against the rear echelons. Deserters later informed us that there were at least twenty-eight thousand Turkish cavalrymen in this encounter. When the hostile lines finally milled together, the Franks prayed to God and rushed forward. Without delay the ever-present Lord ‘strong and mighty in battle’ shielded his children and cast down the pagans. Thereafter the Franks chased them almost ten miles from the battle site to their highly fortified fortress. Upon the sight of this débâcle the occupants of the castle burned it and took to flight.† This outcome caused joy and jubilation in the camp, because we considered the burning of the fortification as another victory.

At the same time fighting broke loose everywhere in the direction of Antioch because our foes planned a two-pronged attack – one from the besieged and one from the unexpected auxiliary troops. God showed no favourites and battled along with the footmen while he smiled upon the knights, so that the victory of the footmen over the besieged was no less than the knights’ repulse of the reinforcements. With the battle and booty won, we carried the heads of the slain to camp and stuck them on posts as grim reminders of the plight of their Turkish allies and of future woes for the besieged. Now as we reflect upon it, we have concluded that this was God’s command because the Turks had formerly disgraced us by fixing the point of the captured banner of the blessed Mary in the ground. Thus God disposed that the sight of lifeless heads of friends supported by pointed sticks would ban further taunts from the defenders of Antioch.

Ambassadors of the king of Babylon [Egypt] were present during these events, and upon viewing the miracles which God performed through his servants, praised Jesus, son of the Virgin Mary, who through these wretched beggars trampled under foot the most powerful tyrants.* In addition, they promised friendship and favourable treatment, and reported benevolent acts of their king to Egyptian Christians and our pilgrims. Consequently, our envoys, charged with entering into a friendly pact, departed with them.

Contemporaneous with these events our princes decided to fortify an area on a hill which commanded the tents of Bohemund and thereby to thwart any and all possible enemy attacks against our tents.† Upon completion of this work our fortifications were so strengthened that we were to all intents and purposes in an enclosed city made strong by work and natural terrain. Thus this new fortress, lying to our east, as well as the walls of Antioch and the nearby protecting marsh, guarded our camp and restricted attacks from the besieged to areas near the gates. Moreover, a river flowed to the west, and to the north an old wall wound its way down the mountain to the river. The plan of strengthening another fortification on the little mountain situated above the Turkish bridge also met with public approval, but siege machines which were built in camp proved useless.

In the fifth month of the investment at the time our ships carrying provisions docked in port, the besieged began to block the way to the sea and to kill supply crews.‡ At first the Turks threatened at all times largely because the indisposition of our leaders to retaliate emboldened them. To counter these dangers we finally decided to fortify the camp near the bridge. In view of the absence of many of our forces at the port, the count and Bohemund were elected to guard the absentees’ return as well as to carry back mattocks and other tools necessary for construction of the new fort. Upon learning of the mission of Raymond and Bohemund, the besieged began their usual attacks. In turn, our troops both unwary and disorderly advanced only to be shamefully scattered and routed.

When on the fourth day as the count and Bohemund with a great multitude, secure as they thought in this rabble, returned from port, they were spied upon by the Turks. But why make a longer story of it? There was a fight, our troops fled and we lost almost three hundred men and no one knows how much in spoils and arms. While we, like cattle in the mountains and crags, were being killed and dashed down, aid from the camp moved against the Turks, who then turned from the slaughter of the fugitives. Lord God, why these tribulations? Our forces within the camp and those without who had the services of the two greatest leaders in your army – Raymond and Bohemund – were overcome and vanquished. Shall we flee to the camp or shall the guardians of the camp flee to us? ‘Arise, O Lord. Help us in honour of thy name.’* If the report of the defeat of the princes had been heard in the camp, or if by chance we had learned of the rout of the army contingents, then collectively we would have fled. Now at the right moment the Lord aided us and incited those whom he had formerly cowed to be foremost in battle.

Upon viewing our stolen goods and his victory as well as the rashness of a few Christians, Yaghi Sayan,† commander of Antioch, sent his knights and footmen from the city. Confident of success, he commanded the gates of Antioch to be closed after them, thereby demanding that his soldiers win the fight or perish. In the mean time the crusaders, as ordered, moved forward gradually, but the Turks ran hither and thither, fired arrows, and boldly attacked our men. Our soldiers, unchecked by Turkish manoeuvres, suffered but awaited the time for a mass assault. The flowing tears and plaintive prayers made one think that God’s compassion must be in the offing.

When the time for the encounter came, a very noble Provençal knight, Isoard of Ganges, accompanied by 150 footmen, knelt, invoked the aid of God, and stirred his comrades to action by shouting, ‘Charge! Soldiers of Christ!’ Thereupon he hurled himself against the Turks, and as our troops rushed to the attack, the haughtiness of the enemy was shattered. The gate was closed, the bridge was strait, but the river was very broad. What then? The panicky Turks were either smashed to the ground and slaughtered or crushed with stones in the river, for flight lay open to no one. Peace would have come to Antioch on this day had not Yaghi Sayan swung open the gate. I myself heard from many participants that they knocked twenty or more Turks into the river with bridge railings. There Godfrey distinguished himself greatly, for he blocked the Turks scrambling to enter the gate and forced them to break into two ranks as they ascended the steps.

Following a religious service, the happy victors marched back to camp with great spoils and many horses. Oh! How we wish you fellow Christians who follow us in your vows could have seen this noteworthy event! Namely, a horseman, fearful of death, hurriedly plunged into the deep waters of the river only to be grabbed by his fellow Turks, thrown from his horse, and drowned in the stream along with the mob which had seized him. The hardships of the encounter were rewarded by the sight of the returning masses. Some running back and forth between the tents on Arabian horses were showing their new riches to their friends, and others, sporting two or three garments of silk, were praising God, the bestower of victory and gifts, and yet others, covered with three or four shields, were happily displaying these mementoes of their triumph. While they were able to convince us with these tokens and other booty of the greatness of their battle prowess, they could give no exact information on the number of dead because the Turkish rout ended at night, and consequently the heads of the fallen enemy had not been brought to camp.

However, on the following day at the site of a proposed fortification in front of their bridge, the bodies of some of our foes were discovered in a ditch close to a mountain which served as a Saracen cemetery. Excited by the sight of Turkish spoils, the poor violated all of the tombs and so, having disinterred the Turkish cadavers, there remained no doubt of the extent of the victory. The dead numbered around fifteen hundred, and I remain silent on both those buried in the city and those dragged under the waters of the river. But the corpses were hurled into the Orontes lest the intolerable stench interfere with construction of the fort.

Indeed, the sailors who in the flight of the count and Bohemund had been routed and wounded were still terror-stricken and sceptical of the outcome. But, as if strengthened by the sight of the great number of dead, they began to praise God, who is accustomed to chastening and cheering his children. So, by God’s decree it happened that the Turks, who killed the food porters along the coast and river banks and left them to the beasts and birds, in turn made food in that place for the same beasts and birds.

Following acknowledgement of victory and attendant festivities as well as completion of the fort, Antioch was besieged from the north and south. Then debate ensued over the choice of a prince as guardian of the new fort, since a community affair is often slighted because all believe it will be attended to by others.* While some of the princes, desirous of pay, solicited the vote of their peers for the office, the count, contrary to the wishes of his entourage, grabbed control, partly in order to excuse himself from the accusation of sloth and avarice and partly to point the way of force and wisdom to the slothful.

During the preceding summer Raymond had been weakened by a grave and long illness and consequently was so debilitated during the winter that it was reported he was disposed neither to fight nor to give. Although he had performed great services, he was considered an unimportant person because the people believed he was capable of more effort. He bore such enmity from the doubt cast upon his Christian strength that he was almost alienated from the Provençals. Meanwhile, the count disregarded these insults, trusting that the besieged Antiochenes, for the most part overcome, would flee; but, on the contrary, he was surrounded by his foes one morning at daybreak.

A great miracle of God’s protection manifested itself when sixty of our men withstood the assault of seven thousand Saracens; and even more marvellous, on the preceding day a torrent of rain drenched the fresh earth and thus filled the fosse around the castle. As a result no obstacles but the strength of the Lord hindered the enemy. Yet I think that it is not the time to ignore the great courage of several knights who, as guards of the bridge, were now isolated and found themselves unable to flee since a distance of an arrow’s flight lay between them and their fortress. Pushing forward against the Saracens in a circular formation, these knights advanced to the corner of a nearby house where they met courageously and intrepidly the enveloping attack, both the fury of the arrows and the cloud of rocks.

At the same time the noise of combat attracted our forces, and as a result the fort was saved from its attackers; however, despite the fact that the Turks gave up their drive at the sight of approaching reinforcements, those in the rearguard were destroyed although their bridge was close by. Again the ditch and the walls of the fortress were repaired so that the carriers of food could go and return safely from port. Consequently, the envy suffered by the count calmed to the extent that he was called father and defender of our army, and following these events Raymond’s reputation rose because single-handed he had met the onslaughts of the enemy. After the blockade of the bridge and the bridge gate, the Turks made sorties from another gate located to the south and near the river. From here they led their horses to a nook, which afforded an excellent pasture between the mountains and the river.

After reconnoitring and setting a time, some of our men circled around the city by crossing a rough mountain while others forded the river, and the combined party led away two thousand horses from the pasture. This number did not count mules and she-mules which were retaken. It is to be noted that formerly many she-mules en route from the sea to Antioch had been stolen by the Turks, and these animals now recovered were given back to their owners on proper identification.

Soon afterwards Tancred fortified a monastery situated on the other side of the river, and in view of its importance in blockading the city the count of Toulouse gave Tancred 100 marks of silver, and other princes contributed according to their means.* Thus it pleases me to note that, although we were fewer in numbers, God’s grace made us much stronger than the enemy. At this time arriving couriers often reported enemy reinforcements; and, in fact, these rumours spread not only from Armenians and Greeks but also from residents of Antioch. I call to your attention that the Turks occupied Antioch fourteen years before [1084] and, in the absence of servants, had used Armenians and Greeks as such and had given wives to them. They, nevertheless, were disposed to flee to us with horses and arms as soon as escape was possible. Many timid crusaders along with the Armenian merchants took flight as rumours spread, but on the other hand able knights from various fortresses returned and also brought, adjusted and repaired their arms. When the waning cowardice disappeared sufficiently, and boldness – sufficient at all times to brave all perils with and for brothers – returned, one of the besieged Turks [Firuz] confided in our princes that he would deliver Antioch to us.

Now when my lord Bohemund heard rumours that an immense force of Turks† was coming to attack us, he thought the matter over and came to the other leaders, saying, ‘Gentlemen and most valiant knights, what are we to do? We have not sufficient numbers to fight on two fronts. Do you know what we might do? We could divide our forces into two, the foot-soldiers staying here in a body to guard the tents and to contain, so far as possible, those who are in the city. The knights, in another band, could come out with us against our enemies, who are encamped not far off, at the castle of Aregh beyond the Orontes bridge.’

That evening the valiant Bohemund went out from the camp with other very gallant knights, and took up his position between the river and the lake. At dawn he ordered his scouts to go out forthwith and to discover the number of Turkish squadrons, and where they were, and to make sure what they were doing. The scouts went out and began to make careful enquiries as to where the army of the Turks was hidden, and they saw great numbers of the enemy coming up from the river in two bands, with the main army following them. So the scouts returned quickly, saying, ‘Look, look, they are coming! Be ready, all of you, for they are almost upon us!’ The valiant Bohemund said to the other leaders, ‘Gentlemen and unconquered knights, draw up your line of battle!’ They answered, ‘You are brave and skilful in war, a great man of high repute, resolute and fortunate, and you know how to plan a battle and how to dispose your forces, so do you take command and let the responsibility rest with you. Do whatever seems good to you, both for your own sake and for ours.’ Then Bohemund gave orders that each commander should arrange his own forces in line of battle. This was done, and they drew up in six lines. Five of them together charged the enemy, while Bohemund held his men a little in reserve. Our army joined battle successfully and fought hand-to-hand; the din arose to heaven, for all were fighting at once and the storm of missiles darkened the sky. After this the main army of the Turks, which was in reserve, attacked our men fiercely, so that they began to give back a little. When Bohemund, who was a man of great experience, saw this, he groaned, and gave orders to his constable, Robert Fitz-Gerard, saying, ‘Charge at top speed, like a brave man, and fight valiantly for God and the Holy Sepulchre, for you know in truth that this is no war of the flesh, but of the spirit. So be very brave, as becomes a champion of Christ. Go in peace, and may the Lord be your defence!’ So Bohemund, protected on all sides by the sign of the Cross, charged the Turkish forces, like a lion which has been starving for three or four days, which comes roaring out of its cave thirsting for the blood of cattle, and falls upon the flocks careless of its own safety, tearing the sheep as they flee hither and thither. His attack was so fierce that the points of his banner were flying right over the heads of the Turks.

The other troops, seeing Bohemund’s banner carried ahead so honourably, stopped their retreat at once, and all our men in a body charged the Turks, who were amazed and took to flight. Our men pursued them and massacred them right up to the Orontes bridge. The Turks fled in a hurry back to their castle, picked up everything they could find, and then, having thoroughly looted the castle, they set fire to it and took to flight. The Armenians and Syrians, knowing that the Turks had been completely defeated, came out and laid ambushes in passes, killing or capturing many men.

Thus, by God’s will, on that day our enemies were overcome. Our men captured plenty of horses and other things of which they were badly in need, and they brought back a hundred heads of the dead Turks to the city gate, where the ambassadors of the amir of Cairo* (for he had sent them to our leaders) were encamped. The men who had stayed in the camp had spent the whole day in fighting with the garrison before the three gates of the city. This battle was fought on Shrove Tuesday, 9 February, by the power of Our Lord Jesus Christ, who with the Father and the Holy Ghost liveth and reigneth, One God, world without end. Amen.

Our men, by God’s will, came back exulting and rejoicing in the triumph which they had that day. Their conquered enemies, who were totally defeated, continued to flee, scurrying and wandering hither and thither, some into Khorasan and some into the land of the Saracens. Then our leaders, seeing that our enemies who were in the city were constantly harrying and vexing us, by day and night, wherever they might do us harm, met in council and said, ‘Before we lose all our men, let us build a castle at the mosque which is before the city gate where the bridge stands, and by this means we may be able to contain our enemies.’ They all agreed and thought that it was a good plan. The count of St Gilles was the first to speak, and he said, ‘Help me to build this castle, and I will fortify and hold it.’ ‘If you wish it,’ replied Bohemund, ‘and if the other leaders approve, I will go with you to St Simeon* and give safe conduct to the men who are there, so that they can construct this building.† The people who are to stay here must keep watch on all sides so as to defend themselves.’

The count and Bohemund therefore set out for St Simeon’s Port. We who stayed behind gathered together, and were beginning to build the castle, when the Turks made ready and sallied out of the city to attack us. They rushed upon us and put our men to flight, killing many, which was a great grief to us.

Next day the Turks, realising that some of our leaders were away, and that they had gone to the port on the previous day, got ready and sallied out to attack them as they came back from the port. When they saw the count and Bohemund coming back and escorting the builders, they began to gnash their teeth and gabble and howl with very loud cries, wheeling round our men, throwing darts and shooting arrows, wounding and slaughtering them most brutally. Their attack was so fierce that our men began to flee over the nearest mountain, or wherever there was a path. Those who could get away quickly escaped alive, and those who could not were killed. On that day more than a thousand of our knights or foot-soldiers suffered martyrdom, and we believe that they went to heaven and were clad in white robes and received the martyr’s palm.

Bohemund did not follow the same route which they had followed, but came more quickly with a few knights to where we were gathered together, and we, angry at the loss of our comrades, called on the name of Christ and put our trust in the pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre and went all together to fight the Turks, whom we attacked with one heart and mind. God’s enemies and ours were standing about, amazed and terrified, for they thought that they could defeat and kill us, as they had done with the followers of the count and Bohemund, but Almighty God did not allow them to do so. The knights of the true God, armed at all points with the sign of the Cross, charged them fiercely and made a brave attack upon them, and they fled swiftly across the middle of the narrow bridge to their gate. Those who did not succeed in crossing the bridge alive, because of the great press of men and horses, suffered there everlasting death with the devil and his imps; for we came after them, driving them into the river or throwing them down, so that the waters of that swift stream appeared to be running all red with the blood of Turks, and if by chance any of them tried to climb up the pillars of the bridge, or to reach the bank by swimming, he was stricken by our men who were standing all along the river bank. The din and the shouts of our men and the enemy echoed to heaven, and the shower of missiles and arrows covered the sky and hid the daylight. The Christian women who were in the city came to the windows in the walls, and when they saw the wretched fate of the Turks they clapped their hands secretly. (The Armenians and Syrians who were under the command of Turkish leaders had to shoot arrows at us, whether they liked it or not.) Twelve amirs of the Turkish army suffered death in body and soul in the course of that battle, together with fifteen hundred more of their bravest and most resolute soldiers, who were the best in fighting to defend the city. The survivors no longer had the courage to howl and gabble day and night, as they used to do. Darkness alone separated the two sides, and night put an end to the fighting with darts, spears and arrows. Thus our enemies were defeated by the power of God and the Holy Sepulchre, so that henceforth they had less courage than before, both in words and works. On that day we recouped ourselves very well, with many things of which we were badly in need, as well as horses.

Next day, at dawn, other Turks came out from the city and collected all the stinking corpses of the dead Turks which they could find on the river bank, except those that were concealed in the actual river bed, and buried them at the mosque which is beyond the bridge before the gate of the city, and together with them they buried cloaks, gold bezants, bows and arrows, and other tools the names of which we do not know. When our men heard that the Turks had buried their dead, they made ready and came in haste to that devil’s chapel, and ordered the bodies to be dug up and the tombs destroyed, and the dead men dragged out of their graves. They threw all the corpses into a pit, and cut off their heads and brought them to our tents (so that they could count the number exactly), except for those which they loaded on to four horses belonging to the ambassadors of the amir of Cairo and sent to the sea coast. When the Turks saw this, they were very sad and grieved almost to death, for they lamented every day and did nothing but weep and howl. On the third day* we combined together, with great satisfaction, to build the castle already mentioned, with stones we had taken from the tombs of the Turks. When the castle was finished, we began to press hard from every side upon our enemies whose pride was brought low. But we went safely wherever we liked, to the gate and to the mountains, praising and glorifying our Lord God, to whom be honour and glory, world without end. Amen.

Stephen, Count of Blois and Chartres, presents one of the First Crusade’s most enigmatic figures. Hen-pecked by his redoubtable bluestocking wife, Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror, Stephen acquitted himself well prior to the siege of Antioch. There, his talents were recognised by his being appointed ductor of the whole expedition, a reflection of the growing institutional ties that the leaders imposed on themselves to enhance their chances of success. Yet less than ten weeks later Stephen fled on the night of 2 June 1098, only hours before the city fell. After a concerted campaign of domestic humiliation by his ashamed wife, he returned to the Near East with the ill-fated 1101 expedition only to be killed at the battle of Ramleh in 1102, his reputation partly restored.*

Count Stephen to Adela, his sweetest and most amiable wife,† to his dear children, and to all his vassals of all ranks – his greeting and blessing.

You may be very sure, dearest, that the messenger whom I sent to give you pleasure left me before Antioch safe and unharmed, and through God’s grace in the greatest prosperity. And already at that time, together with all the chosen army of Christ, endowed with great valour by him, we had been continuously advancing for twenty-three weeks towards the home of our Lord Jesus. You may know for certain, my beloved, that of gold, silver and many other kind of riches I now have twice as much as your love had assigned to me when I left you. For all our princes, with the common consent of the whole army, against my own wishes, have made me up to the present time the leader, chief and director of their whole expedition.

You have certainly heard that after the capture of the city of Nicaea we fought a great battle with the perfidious Turks and by God’s aid conquered them. Next we conquered for the Lord all Asia Minor and afterwards Cappadocia. And we learned that there was a certain Turkish prince Assam,‡ dwelling in Cappadocia; thither we directed our course. All his castles we conquered by force and compelled him to flee to a certain very strong castle situated on a high rock. We also gave the land of that Assam to one of our chiefs and in order that he might conquer the above-mentioned Assam, we left there with him many soldiers of Christ. Thence, continually following the wicked Turks, we drove them through the midst of Armenia, as far as the great river Euphrates. Having left all their baggage and beasts of burden on the bank, they fled across the river into Arabia.