Ayurveda is the science of health and healing developed in India, where it has been in use for millennia. And thanks to its widespread use today in both India and abroad, and also thanks to brilliant expositors such as Deepak Chopra (2000), Vasant Lad (1984), and David Frawley (1989), Ayurvedic concepts such as the doshas have become more familiar in the United States.

Just to give you an example, I was at a party recently and this complete stranger asked me out of the blue, “So what's your body type? Are you a vata, a pitta, or a kapha?” Now vata, pitta, and kapha are names of Ayurvedic doshas. The implication was clear to me. Before this person would start a conversation with a stranger, she needed to know the Ayurvedic typology of the person, which, according to Ayurveda, is determined by a person's dominant dosha. Even a decade ago it used to be astrology—“Are you a Sagittarius?”—that was used to break the ice between strangers. Astrology, move over.

But what is a dosha? Modern Ayurvedic physicians can tell you all about the imbalances of your doshas from your symptoms of unwellness but would be quite vague in defining them. They may say that physically these doshas are related to body humors, vata with intestinal gas, pitta with bile, and kapha with phlegm. If you are knowledgeable as to how medicine was practiced in earlier days in the West, you will recognize the importance of humors.

In the West, four humors were considered to be important. Choleric humor represented by yellow bile clearly corresponds to Ayurvedic pitta. The phlegmatic humor was represented by phlegm, corresponding to kapha in the Ayurvedic system. The other two were the melancholic humor as represented by black bile and the sanguine humor as represented by blood. These last two correspond to the humor of vata in the Ayurvedic tradition. Even today, our language says melancholy denotes a state of depression, which concurs with the Ayurvedic view that excess vata is most responsible for chronic diseases that may cause depression.

The medicine of earlier days also connected these doshas to the “five elements,” a description of the material nature—earth, water, air, fire, and ether—then prevalent. Vata is air but needs the vessel of ether (empty space) to move; so vata reflects both ether and air. Pitta is clearly (digestive) fire, and since it needs the vehicle of water, it is seen to reflect the elements of fire and water. And kapha is water whose container is earth (the element, not the planet). So kapha reflects both water and earth.

But if this is all there is to Ayurveda, and you are a Western medicine practitioner, you will not be impressed. The old system is arbitrary, simplistic, and, of course, based on an archaic worldview. Compared to this, the worldview on which modern (allopathic) medicine is based is sophisticated. If one points out the empirical success of the Ayurvedic practice today, all the Western physician can do is shrug. There seems to be no way of understanding the importance of vata, pitta, and kapha within the current scientific worldview.

Many proponents of Ayurveda have begun to dispense with the overarching model, or at least to de-emphasize it. They may say that these doshas are connected with the processes of the body as follows:

Vata: ordinary movement (such as circulation of blood)

Pitta: transformative movement (such as digestion)

Kapha: structure, or that which holds the structure together (such as the lining of the lungs)

These physicians recognize that the important thing is not to get bogged down with worldview questions. The human system may be much too complex to develop a proper theory of it that is able to connect all the way to the fundamentals on which the worldview is based.

Instead, these pragmatic Ayurvedic physicians use the concept of the doshas to classify all humans into seven types:

In principle, there is also an eighth body type—the perfectly balanced one—but this is very rare.

The fundamental assumption of Ayurveda is that one is born with a given body type—a particular “base level” imbalance (called prakriti in Sanskrit). The contingencies of life, lifestyle, and environment take one to further imbalances (bikriti), causing disease. Ayurvedic medicinal herbs, diets, and practices try to bring one back to the base level imbalance. Theoretically, it may seem desirable to try to correct even the base level imbalance, but that is very difficult to do and is usually not attempted.

In our formative years, when the structure is being built, kapha is said to dominate. In the middle portion of life, pitta dominates. In the declining years, vata tends to dominate. Since disease happens more when we are middle-aged and older, clearly most disease must be vata imbalance. Next most prevalent is pitta imbalance. Kapha imbalance is the least common. Our modern lifestyle also aggravates vata. So on the face of it, Ayurveda gives us a simple message: Watch out for that aggravated vata.

Nevertheless, the practice of Ayurveda is subtle. Even modern allopathic medicine has begun to emphasize lifestyle (the social theory of disease). For example, heart disease is associated with the so-called type A personality and lifestyle (hyperactive, overanxious, do-do-do) even by allopathic physicians. But there is a difference in the approach of Ayurveda, which takes account of the fact that not everybody with a type A personality gets heart disease. Ayurveda attempts to bring the patient back to one's base level dosha distribution, to one's prakriti. If the base level is already type A, Ayurveda does not bother to correct it. It is this individualized nature of Ayurveda that makes it so useful in treating chronic disease.

Nevertheless, major questions remain. Why does each one of us have a particular prakriti, a base level of dosha imbalance? Clearly Ayurveda, judging from its success, complements allopathic medicine, but how? Is there a scientific theory behind this way of looking at our body types that give us our tendencies toward disease, and healing?

At a deeper level, Ayurveda is said to be based on a more extended picture of ourselves than today's allopathic medicine (and modern Ayurveda by default), which recognizes us to be only the physical body. In addition to the physical body, Ayurveda allows us to be the movements of a vital body and, less important in the present context, the movements of a mental and supramental body as well, all grounded in consciousness, which is the ground of all being.

The physical body forms, the cells and organs of the body, are representations of vital body blueprints, which Ayurveda recognizes, and in so recognizing, Ayurveda is able to point out more ways that a person may get sick. Recall that in modern biology, Rupert Sheldrake has made the same point: Nonphysical morphogenetic fields (a more scientific name for the vital body) provide the blueprint for making physical form.

For allopaths, sickness involves chemical (and physical) functions of the physical body that have gone awry, and treatment like-wise consists only of correcting the faulty chemistry (or physics). For modern Ayurvedic physicians, likewise, illness is at the physical level only, and imbalance considered for treatment pertains to physical features such as vata, pitta, and kapha; it's a bit more subtle than the allopathic approach.

But in deep-level Ayurveda, illness can also be the result of faulty nature, of faulty movements of the blueprints, of the vital body. Recall that these movements are associated with the programs that run the vital functions of the physical organs (the representations of the blueprints). Clearly, unless you correct the fault at the vital level, you can never make organ representations behave properly to carry out your vital function in a way that corresponds to physical health. Thus traditional Ayurveda at a deep level puts more emphasis on achieving a balance of the vital body qualities (the same is true of Chinese medicine), which in the Ayurvedic system are the precursors of the doshas.

This deep-level Ayurvedic scenario of illness has a clearer complementarity with allopathy (because it introduces the complementary disease-causing scenario involving the vital body) than does modern Ayurveda, which deals with the physical doshas alone. But there is a problem: What is the vital body in relation to the physical?

Here the traditionalist claims that the vital body is nonphysical. Unfortunately for the modern Ayurvedic physician, such a claim is precarious. Hasn't molecular biology eliminated all forms of vitalism or nonphysical life force? The postulate of a vital body also raises the specter of dualism and the question, How does a nonphysical vital body interact with the physical?

But this dualistic view of the vital body (and of consciousness itself) is a product of the myopic “single” vision of Newtonian thinking. In physics, we have replaced Newtonian classical physics with quantum physics, and the implication of this paradigm shift in physics is gradually being worked out for other fields of human endeavor such as medicine. In quantum thinking, vitalism is no longer a dualism. In other words, in quantum thinking we can postulate a nonphysical vital body without falling into the pitfall of interaction dualism.

As mentioned earlier, in quantum physics, all objects are waves of the possibilities of consciousness, which is the ground of all being; these possibilities can be classified as physical and vital (and mental and supramental). These possibility objects become the “things” of our experience when consciousness chooses out of its possibilities the actual experience in a particular quantum measurement (an event that physicists call collapse of the possibility wave).

Undeniably, an experience has a physical component, but if you look carefully, it also comes with a feeling that is its vital component (and thoughts and intuition are the mental and supramental components). This eliminates dualism, because the physical and vital can be seen to be functioning in parallel while consciousness maintains the parallelism (see figure 4).

So vital energies are what we feel in our vital body when we experience our physical organs. When these feelings are not “right,” we feel illness. But we have a certain predisposition in our processing of vital energies. It is these vital predispositions that are the precursors of the physical “defects” called the doshas in Sanskrit.

Consciousness collapses vital feelings along with the correlated physical organ (for the moment, let's leave out the mental and supramental aspects of our experience) for its experiences of living. We have to remember that our physical bodies are in constant flux; our cells and organs are being constantly renewed with the help of the food molecules that we eat. We also have to remember that the quantum possibilities of the vital body consist of a possibility spectrum (with a corresponding probability distribution determined by the quantum dynamics of the situation) of the morphogenetic fields, the blueprints of the vital body. The dynamic laws of the vital body functions and the contexts of its movement are contained in the supramental.

When we are first making representations, as when the one-celled embryo becomes a multicellular form through cell division, our choice of the vital body blueprint is free and the physical representation has a chance to correspond to optimal health under any internal and external environmental condition. In other words, though the vital body function and its laws, the supramental archetype, are always the same, we are free to choose the particular morphogenetic field, the blueprint that corresponds to that function.

This freedom of choice as to which vital blueprint will be used for physical representation-making is exerted according to the context of the external and internal environment of the particular physical body under construction. Of course, even at this stage, disease may arise because of (1) defects of the representation-making apparatus (the inherited genes), and (2) the inadequacy of the building material of the representation (our food intake and nutritional status). But given proper genetic endowment and proper nutrition, when we first build our physical body from the vital body instructions, we can be creative. And with creativity, we can even overcome some of the shortcomings of the genetic predisposition and/or malnutrition, and even environmental problems such as bacteria and viruses.

Thus it is that most children enjoy good health. However, some children suffer from bad health and this even without environmental contributions such as bacteria and viruses. Moreover, it is well known that diseases such as heart disease can be traced to indications appearing at an earlier age. What gives?

On our way to adulthood, by which time our physical bodies (the cells and organs) have been renewed many times, something called conditioning takes place, and this compromises our creativity. Conditioning is the result of the modification of probabilities to gain more weight for a previously collapsed possibility, a past response; it is due to the reflection in the mirror of memory. (See Goswami 2000, for more details.) With conditioning, we no longer possess the leeway to choose our vital blueprint to suit the environmental situation; instead we become predisposed to use the same blueprint that we have used before. If that blueprint is faulty, faulty representations will result.

There is one other alternative. Often, as we renew our body, we use more than one vital blueprint of a vital function to make the physical representation for that vital function; if so, both blueprints will be part of our vital repertoire. Suppose that in a subsequent case of organ-making, certain new environmental challenges are present that require a creative response. In that case, even though consciousness may not be able to choose a response (a vital blueprint) entirely outside the learned repertoire, it still may meet the environmental challenges partway by choosing a blueprint that is a combination of relevant blueprints learned in the past.

This kind of secondary creativity is sometimes called situational creativity (see Goswami 1999) in contrast to an entirely new response in a new context, which is called fundamental creativity.

In this way, there are three qualities of the vital body:

All three are needed for the proper optimal functioning of the vital-physical bodies. Any imbalance will cause defects—the doshas, at the physical level. Corresponding to the three vital qualities, there are three doshas or defects of the representations. If there is too much tejas or fundamental creativity in the building of the body organs with the help of the vital morphogenetic fields, it results in the pitta type of body. Use of too much vayu or situational creativity at the vital body level gives us the vata type of body; and too much ojas produces the kapha type. The doshas are the “waste products” of how we use our vital body qualities to make form.

Another way of looking at this is to see tejas as the transformative vital energy an excess use of which produces a preponderance of metabolism in the physical makeup of the body and thus the dosha of pitta. Similarly, an excess of vayu—excessive and fickle vital movement within known contexts—translates as the dosha of vata, whose main characteristics are movement, fickleness, and changeability. An excess use of ojas—stable conditioned movements of the vital body—translates into the preponderance of the dosha of kapha, whose main characteristics are stability and structure.

There is a similarity in the three vital qualities, the tejas-vayu-ojas trio, to the three qualities of mind called the gunas. First, let's recognize that the Sanskrit word guna means “quality” in English. Second, later discussions will show that the mental gunas have the same origin as the vital gunas. They correspond to the three ways that the quantum mind can be used to process things: fundamental creativity, situational creativity, and conditioning (see chapter 14). Finally, note that the gunas (qualities) improperly used in out-of-balance fashion give rise to doshas (defects) at the physical level.

One question I will briefly deal with is about the origin of prakriti and why we have a self-styled dosha imbalance early on. Since doshas are the by-products of the more subtle vital qualities, we can ask: Are we born with an imbalance of these vital qualities? If so, why? The fact that many children suffer from chronic illness supports the view that there may be innate imbalances of the vital qualities of tejas, vayu, and ojas that we are born with. Why these imbalances? The succinct answer is: reincarnation.

I have previously introduced reincarnation (see chapters 3 and 6). Reincarnation is part and parcel of all Eastern systems of thought, and Ayurveda is no exception. The study of reincarnation falls within the purview of science since the demonstration of the existence of reincarnation proves the existence of the so-called subtle bodies—especially the vital and the mental (see chapter 3). The stimuli we experience in our lives and our responses to them produce brain memory. When a stimulus is repeated, the quantum probability of the response is more heavily weighted toward the previous response.

I call this quantum memory of the brain's response patterns. And since the mind is correlated with the brain, the mind also develops quantum memory of its conditioned habit patterns. It is this quantum memory, the modification or conditioning of the mind as we live it, that is reincarnated (see chapter 6). Now the inheritance of these modifications of the mind from previous lives, called karma in Eastern thought, has been empirically demonstrated (see Goswami 2001), giving further credence to the idea of reincarnation.

Traditionally, karma is understood as mental karma, mental propensities that we bring with us from our past lives. But a little thought shows that there can also be vital karma, vital propensities that we develop during our lives and that can then transmigrate to another life in the same way that mental karma is transmigrated (see Goswami 2001). The vital body is correlated to physical body organs at the chakras. Experiences and our response to them produce quantum memories for the organs that propagate to the vital body, giving rise to individual vital body propensities.

It is these vital propensities that we inherit from our past lives that give us innate imbalances of the vital qualities (fundamental creativity or tejas, situational creativity or vayu, and conditioned behavior or ojas) at the vital level. These innate vital propensities, imbalances notwithstanding, are as important in shaping our physical body as the conventional nature (our genetic endowment) and nurture (contribution of the physical environment).

Eventually, the innate imbalance of vital qualities that we are born with gives rise to prakriti, the natural base level imbalance of the doshas. Preponderance of tejas leads to the imbalance of pitta, and so forth, as described earlier.

The particular combination of doshas that we develop as we grow up, our physical prakriti or body type, is a homeostasis. Therefore, our physical body functions optimally when we remain at this homeostasis. If, however, our imbalances of vital qualities are not corrected and continue unabated, deviations from this homeostasis take place and disease is this movement away from the natural dosha homeostasis.

In this way, Ayurvedic healing can take two tracks. First, the obvious one: Correct the physical problems arising from the dosha imbalance beyond dosha prakriti at the physical level itself. Some of the Ayurvedic treatments are designed with this in mind—panchakarma, a cleansing of the body, for example. But this is only a temporary remedy.

The other track is to correct the imbalances of the vital body qualities. This correction alone can lead to a permanent remedy. This latter track can be practiced in two ways—passive and active. The passive path employs herbal medicine, administering herbs of specific patterns of prana to compensate what is missing. The active path is to transform directly the movements of prana at the vital body level. Breathing practices called pranayama, in which one watches the movements of breath along with the associated vital prana movements, are prime examples of the active path.

General considerations of the vital body as I have described give us an understanding of how doshas arise at the physical level. But how do we connect the doshas with the working of the body organs? We need further insights as to the nature of the vital blueprints or morphogenetic fields.

The ancient seers who discovered Ayurveda intuited something fundamental at this juncture (the founders of Chinese medicine had the same basic idea). It is now recognized that form in the macro-physical world exists in five different states: solid, liquid, gas, plasma, and void or vacuum. This has been obvious since antiquity, except the ancients had different names for the basic forms, such as earth, water, air, fire, and ether, generally referred to as the five elements. The seers of Ayurveda recognized (paraphrased in the language of the quantum) that the vital body possibilities manifested in the same five basic states: earth, water, fire, air, and ether. Moreover, in the form-making of the physical body, the vital earth is correlated with the physical earth, vital fire with the physical fire, and so forth.

Now the tejas quality of the vital body is transformative, fundamental creativity. Thus it uses the vital fire, which correlates with fire at the physical level in the digestive system. Similarly, vayu is the empire-building situational creativity at the vital level and uses the air and ether aspects of the vital to represent movement in the physical, be it in the intestines or the blood vessels or the nerves. Finally, ojas is stability and uses the vital elements corresponding to solid earth and liquid water to make the physical elements with structure and stability.

If there is too much tejas, too much vital fire in physical form-making, there would also be the by-product of too much physical fire—a preponderance of the dosha of pitta. Similarly, too much vayu, too much use of vital air and ether results in the dosha of vata; and too much ojas means too much use of earth and water, which leads to the dosha of kapha.

So pitta resides mainly in the digestive system (stomach and small intestine) as excess acidity. Vata imbalance inhibits pitta and thus exists mainly in the large intestine (as intestinal gas), but also in the lungs and the respiratory system, the circulatory system, and the nerves. Kapha inhibits movement of vata and thus resides as phlegm mainly in the respiratory system and also in the stomach. In summary, the lower third of the body is thus said to be the domain of vata, the middle third the domain of pitta, and the upper third, the domain of kapha.

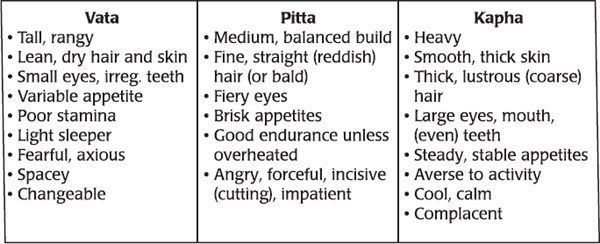

In the foregoing I singled out a few of the most telling characteristics for each dosha to distinguish among them. But if you want to know which dosha or body type you belong to, a more detailed list is helpful. This is given in figure 12. If you are a mixed dosha, you will have a mixture of characteristics. Can you tell what your body type is from the list?

Fig. 12. The personality traits of people of the three doshas.

In my opinion, although such tests can tell you your dominant dosha, they cannot tell you your precise prakriti, the precise combination of dosha imbalances that is your particular body- homeostasis. You have to go to a good Ayurvedic diagnostician for that.

Why is knowing your dosha prakriti important? You are having your first lesson in individuality in the medical sense. For an allopath, you are not an individual, you are a machine for which only average or typical behavior can be given. In vital body medicine, you are an individual, a specific mixture of body structures and propensities called doshas. Not only that, you operate best when these doshas are close to their homeostatic base level values which are unique to you.

You can use your dosha information for taking care of yourself; all you need to know is what causes dosha imbalances from the homeostatic level of prakriti, and how to prevent these imbalances. This is the subject of the next few sections.

If you maintain your body according to your physical prakriti or base level imbalances, you breeze through life in good health. Problems arise when there is an imbalance, a disturbance in any of the doshas from this base level. Generally, the imbalance is most likely to be in your own body type, that is, a vata person is more likely to suffer from vata imbalance (overactive vayu at the vital level).

However, there is no strict rule; you can be a kapha person and still suffer from pitta imbalance. How can you tell if there is an imbalance beyond the original level of imbalance indicated in your prakriti? What causes these excess imbalances? One cause is seasonal change; the major one is lifestyle.

There is a seasonal connection for the deviation of dosha imbalances from prakriti that can be predicated on the basis of the theory developed here. When it is hot in the external environment, as in the summer, that is the time for regeneration. Thus tejas is used plentifully, producing excess pitta. When it is cold, it means hibernation, and the stability of ojas is needed (excess of which produces an imbalance of kapha). If cold comes with dryness, the condition is right for vata imbalance. If it is cold and wet (rain or snow), all movement ceases, ojas dominates the vital body, and excess kapha is the result.

Throughout the year, if you are observant, you can see how seasonal changes affect your dosha imbalances. On the East Coast of the United States, when the winter is cold and dry, it is the excess vata that makes people enjoy movement even though it is cold. But in early spring, when the weather turns cold and wet, it is time for excess kapha imbalances, and one tends to catch cold (which most often is due to excess unbalanced kapha). When it is hot and humid in the summer, you can easily notice, especially if you are a pitta type, that excess pitta is causing you problems with acidity. So in summer, we all prefer cool food and drink, but for pitta people, these are a must.

In general, if your body type matches your environment, you have to be extra vigilant about keeping the imbalances from going out of control.

If you are a vata person balanced in your prakriti, you are cheerful, enthusiastic, and full of do-do-do energy. And why not? Whatever changes take place in your life situation, the reservoir of learned contexts of situational creativity at the vital level is able to reestablish your physical body homeostasis.

If, on the other hand, your active life is full of anxieties and worries, your body is full of aches and pains, and even your quality of sleep has given way to restlessness, then ask: Is my vata still in balance? Is my vata still near the base level of my prakriti? Those symptoms are symptoms of vata imbalance irrespective of whether you have vata dominance or not.

One scenario for vata imbalance is common to everyone: As we age, vata tends to be aggravated. It is just part of aging. With this kind of vata aggravation, there is not much we can do. There is sleeplessness, some loss of memory (here is everybody's chance to become the “absent-minded professor”), some aches and pains. Even the appetite will not be like it used to be.

But there are other scenarios. Suppose the change in your life situation is drastic, so drastic that the reservoir of vayu, those learned contexts of situational creativity, is not adequate to make the vital level adjustments in a hurry. So vayu is going to be overworked, causing a lot of vata fallout at the physical level. Situations like this arise in our life when we travel, when we move our residence from one city to another, when we change jobs, at times of divorce or the death of a spouse.

I know. A few years back, in the course of a year, I got divorced, I started courting another woman (whom I later married), I changed jobs, and moved from one city to another much bigger city. On top of this, I got a grant so there was pressure for mental accomplishment that I had not encountered in years. And I was already struggling with aggravated vata due to advancing age. Can you imagine the degree of vata aggravation all this caused? I was becoming so disoriented that the following year I had three auto accidents in a period of six months.

So what's the remedy? Ayurvedic medicine suggests several tracks: proper diet, herbal remedies for vata aggravation, an environment of warmth and moisture, oil massage, certain hatha yoga exercises, a cleansing process called panchakarma, and relaxation. The details of diet and herbal remedies can be found in any good book on Ayurveda.

One advantage of Ayurvedic medicine is that it is mostly common sense. Unless you neglect your imbalance so long that the aggravation becomes severe (in which case the imbalance will lead to the physical symptoms of what we normally call a disease), it is quite possible to use the tracks in the previous paragraph as preventive medicine. You need never go to a doctor.

In my case, my usual regimen of yoga and meditation was unable to cope with the degree of vata aggravation. I never did solve my vata imbalance while living in the big city. Fortunately, the movement of consciousness cooperated, and it was necessary to move away from that city. Within six months, my vata became balanced. The main thing was the relaxed lifestyle of my new habitat. I should mention, however, that my wife helped in several ways: diet with fresh vegetarian food full of prana; long walks in nature; a lot less thinking and much more laughter. One problem concomitant with too much vata is too much mental work and the resulting tendency of taking yourself too seriously; you become full of (hot?) air.

If you are a pitta person, you exude creativity and you are intense. When pitta is balanced you are able to handle your natural intensity with joy because you obviously like being intense. But if the intensity is there and the joy is missing, then pitta is unbalanced.

Do you see how it works? Pitta is a side effect of overworking tejas, of fundamental creativity at the vital level. Tejas helps us build a good digestive system and maintain it with proper renewal as needed. But if the drive, the intensity, becomes too much, tejas is overworked and the result is pitta imbalance.

A common scenario is in our middle years. We have stopped growing, so the pressure on the digestive system and tejas at the vital level is considerably reduced. Unfortunately, the inertia of habit keeps them going at the same level as at a younger age. This overworking of tejas continues until we settle down in the last third of our life. So in our thirties we have to accept a certain aggravation of pitta which results in acidity and heartburn, thinning of hair, vulnerability to stress, and things that take away the joy of intense life.

There are foolish ways to aggravate pitta, such as overworking the digestive system unnecessarily by eating improper food. When we are young, our digestive fire is strong and it is considerably intensified by eating hot and spicy foods. The tejas of the food is all used up for a good cause—growing a healthy body. But when you don't need such intense digestive fire any more, then overworking the system with unneeded tejas will produce pitta imbalance. If you still fail to take notice, you will end up with an ulcer.

Organization is not a forte of creative people of the pitta type. But when such organizational demands are made, the system reacts with anger, frustration, or resentment, the expression of which requires tejas. The excessive use of tejas gives the by-product of excess pitta at the physical level. So stress is a pitta aggravator. If you don't watch it, heart disease may result.

The remedy for pitta imbalance is moderation. Reduce the intake of stimulants such as coffee. Meditate. Take long nature walks. Let that extra intensity be used up in the appreciation of beauty.

As a kapha person, your strong point is strength and stability, which endow you with generosity and affection to give to others, and this giving makes you happy. A kapha person is able to live a long happy life, yet a few glitches may arise.

In our childhood, the body is building itself; ojas is needed in abundance, and occasionally this results in excess kapha. This gives a child susceptibility to colds, sore throats, sinus trouble, and so forth; this susceptibility continues for the rest of the person's life in an otherwise healthy existence. One does not have to be a kapha person to contract this particular consequence of kapha imbalance.

But after our bodybuilding phase is over, vital strength and stability, ojas, with nothing to do has a tendency to produce obesity. This is the sign of kapha imbalance, which can lead to other imbalances if not controlled. Since our culture does not approve of obesity, insecurity results from it. If, in spite of this insecurity, one continues to be generous and giving, it will produce clinging. On the physical side, obesity puts too much stress on the heart and leads to hypertension and difficulty in breathing.

Still another scenario is faulty diet heavy in sweet foods. One manifestation of this route to kapha imbalance is diabetes.

Whereas treating vata imbalance requires a ho-hum life, dealing with kapha imbalance requires the opposite: more stimulation and variety to shake up the inertia. Kapha imbalance treatment also requires weight control, avoidance of sweets, and an exercise routine.

In Ayurveda, great emphasis is put on periodic cleansing of the systems of our body to get rid of excess humors due to the imbalances of vata, pitta, and kapha, also called ama. For example, pitta imbalance will create ama in the intestines. This can be dealt with through periodic cleansing of the affected organs. Panchakarma consists of five such cleansing procedures: therapeutic sweating, nasal cleansing with or without herbs, purgation of the stomach and intestines achieved through herbs or enemas, oil massage, and bloodletting. Panchakarma requires the supervision of a trained Ayurvedic physician.

As mentioned earlier, prescription of Ayurvedic herbs requires a trained physician. Reading books on Ayurveda helps more as preventive medicine and less for healing of an already aggravated condition.

The standard for Ayurvedic herbal medicine is very high. To quote from Charaka, one of the authorities:

A medicine is one which enters the body, balances the Doshas, does not disturb the healthy tissue, does not adhere to them, and gets eliminated out through the urine, sweat, and feces. It cures the disease, gives longevity to the body cells, and has no side effects (quoted in Svoboda and Lade 1995).

A reminder. Ayurvedic healing must be individually designed. Ayurvedic medicine must be prescribed not only with your body type in mind, your dosha prakriti, but also your lifestyle, and your personality. So it is best not to use it as self-help, but to get the help of a trained physician.

I heard a story that illustrates this brilliantly. A brahmin (a Hindu scholastic person) of small physical stature was invited to a king's palace for dinner and he could not help himself and overate. So he came to the king's (Ayurvedic) physician asking help with digestion. The physician gave him a pill but warned him.

“Look, this is very potent medicine that I give to the king himself when he sometimes complains about overeating and digestion. One pill will be too much for you. Cut it in quarters and take only a quarter. Okay?”

“Okay,” said the brahmin.

But when he came home, he had second thoughts. As was customary, he was given some leftovers from the dinner, which he had brought with him. “If I take the whole pill, surely I should be able to digest not only what I have in my stomach now, but also all the rest of the food.” So he ate the rest of the delicious food, took his digestive pill, and went to sleep.

In the morning, the Ayurvedic physician was making the rounds with his son; it just so happened that they were in the neighborhood where the brahmin lived, and the kind physician thought of inquiring how the brahmin was doing. The door to the brahmin's house was unlocked. The physician and his son went in; no one was there. They went all the way to the bedroom and knocked; still no one responded. The physician pushed the door open, and lo! There was nobody on the bed, only some clothes. On examination, the clothes were found to be full of feces.

The physician took one look and realized what must have happened.

“Oh, my God!” he exclaimed.

“What's the matter, father?” The son did not understand.

“The poor brahmin must have taken the whole pill. Look, he digested the food, no doubt, but the pill digested him, also,” said the father, pointing to the feces.

Take the following ideas with you: