As chapter 5 revealed, the Party-state has turned to Internet commentators, commonly referred to as the “fifty-cent army,” to produce seemingly spontaneous pro-state commentary. Such astroturfing efforts often backfire because netizens have wised up to this propaganda tactic, which has resulted in a pandemic of criticism of the state and its fifty-cent army agents. However, struggles for control in the competitive terrain of online discourse are not simply binary interactions between the state and those representing “society.” Chapter 6 argued that through imagining “online enemies of the Chinese nation,” a constituency of netizens has been persuaded by a counter-espionage framing that depicts regime challengers and their sympathizers as saboteurs of the nation rather than fighters for freedom and democracy. This suggests a multi-actor model of online discourse competition that involves the state, its critics, as well as fragmented netizen constituencies with diverse values, beliefs, and identities.

This chapter explores the fragmentary politics of online expression by looking at online communities, especially the “voluntary fifty-cent army” (zidai ganliang de wumao, 自带干粮的五毛). These netizens openly disagree with more radical netizens who directly challenge the regime or even pursue a regime-change agenda. In fact, they have emerged with a stated cause of defending the authoritarian regime on an unpaid basis. This is quite unusual given the liberal-leaning environment of online expression. By examining a selection of their tactics, this chapter reveals not only how members of the voluntary fifty-cent army maintain their identity through constant rhetoric battles with their opponents and amicable interactions among themselves, but also how their daily activities have created online communities in which a regime-defending discourse prevails. My study suggests a more balanced picture of China’s Internet politics than previously available and also illustrates a complex pattern of state–society interaction in a reforming authoritarian regime. The anonymous discourse competition illustrates a struggle in which uncoercive power dominates and provides a chance to demonstrate empirically how creativity, art, and identity spill over into the realm of politics.

FRAGMENTED CYBERSPACE: TOWARD A PUBLIC SPHERE OR A BALKANIZED PUBLIC?

Scholars of Western and Chinese politics have drawn quite diverse conclusions about the impact online expression has on civic participation and politics in general. Given China’s oppressive authoritarian regime, observers of Chinese Internet politics have understandably emphasized the liberalizing and empowering effects of the technology, as well as the state’s efforts to constrain its impact. For instance, the sociologist Guobin Yang argues that the Internet has contributed to the rise of a public sphere, which in his conception is more about “free spaces” than “spaces for rational debate in the Habermasian sense.”1 In fact, with only a few exceptions,2 concerns about the detrimental impact of the Internet on civil society and civic participation are largely nonexistent. Johan Lagerkvist puts this rationale most succinctly; acknowledging that the Internet in China has yet to evolve into a “public sphere,” he sees online communities coalescing around shared affinity and interests as “public sphericules” that represent progress in unlocking the public sphere and serve as “bases for public opinion, social organizing, and the occasional stirring of political mobilization.”3 Although in his 2010 book, After the Internet, Before Democracy, Lagerkvist depicts the Internet as a platform for norms competition, he still frames the regulation, influence, and control of online expression as a “control-and-freedom” struggle between the Party-state and rising subaltern norms. More recent studies have started to focus on the varieties of online activism,4 though few have truly gone beyond the state-versus-social dichotomy to fully appreciate the richness, diversity, and complexity of online expression in China.5 In general, they still tend to implicitly or explicitly assume that the Internet is inherently regime-challenging.

While observers of Chinese Internet politics have hailed the technology for empowering society within an authoritarian regime,6 people who study cyberpolitics elsewhere are less convinced. In addition to studies that question the Internet’s empowering effects,7 many have emphasized its detrimental effects. Matthew Hindman, for example, argues that instead of the Internet making public discourse more accessible, political advocacy communities and blogs follow a “winner-takes-all” distribution with a small number of sites getting most of the resources and attention, turning blogs into a new elite media.8 Others argue that the Internet does not necessarily promote the critical exchange of ideas. For example, Barry Wellman and Milena Gulia have found that many online communities are composed of relatively homogenous groups with similar interests, concerns, and opinions. Such online communities, which are characterized by homophily, tend to foster an empathetic understanding and mutual support rather than encouraging the critical evaluation of each other’s claims.9 A content analysis of posts from BBS forums10 and Usenet newsgroups,11 in which more political discussions take place, also finds high concentrations of like-minded individuals. Thus, the media and politics scholar Lincoln Dahlberg argues that online interaction is fragmented into exclusive groups of similar values and interests.12 In fact, according to Cass Sunstein, rather than simply encouraging group exclusivity, online discussions may even encourage polarization on issues that involve diverse opinions, leading to a “Balkanized public” with users interacting in “information cocoons, or echo chambers of their own design,”13 leading to the entrenchment of various discourses in different communities.

In addition to the state–society confrontation, online expression in China has shown distinctive yet discernible patterns that confirm the perspective of a “fragmented cyberspace.” Some studies have characterized China’s Internet as reflecting China’s fragmented society and have characterized netizens as apolitical,14 tending to withdraw rather than fight for free speech when encountering state censorship.15 Even when taking up explicitly political topics, netizens are divided in terms of their identities, political orientations, and discourse preferences. For instance, the Chinese new media scholar Fang Tang, analyzing posts from randomly sampled users of the “Qiangguo” and “Maoyan” forums, found that more than 82 percent of “Qiangguo” users identify as moderate or ultra-left (43 percent and 39 percent, respectively), whereas 73 percent of “Maoyan” users identify as moderate or ultra-right (63 percent and 10 percent, respectively).16 A content analysis of posts from the same two forums by the Internet researchers Yuan Le and Boxu Yang resulted in similar results (“Qiangguo”: 75 percent left versus 9.5 percent right; “Maoyan”: 21.6 percent left versus 48.4 percent right).17 Debates between leftists and rightists and the rise of cyber-nationalism targeting minority groups and foreign actors18 suggest that online expression in China is pluralized and not always regime-challenging. Moreover, the formation of exclusive online communities of individuals with internally coherent political orientations means that open deliberation among diverse netizen groups may be obstructed. Evidently, according to these studies, Chinese cyberspace is better viewed as a “force field in which different social forces and political interests compete”19 than simply as an emerging public sphere that fosters civic engagement and challenges the Party-state.

Will online expression in China precipitate the formation of a public sphere, or instead create “information cocoons” or even result in a “Balkanized public”? What are the potential implications for authoritarian rule? It is clear that a binary conceptualization of online politics as a confrontation between the state and society neglects external factors that condition and influence online political participation. After all, it makes little sense to ignore factors found in open societies simply because China is an authoritarian regime, particularly since the country has evolved into a much more pluralized society after nearly four decades of economic reform. Moreover, as the content analysis approach20 often falls short of revealing the character of and changing trends in online expression, a closer examination of the dynamics of discourse production and the role of online communities is necessary. This chapter makes such an attempt by tracing how online groups such as the voluntary fifty-cent army engage in political expression, thus incorporating netizens, online communities, and discourse competition into a dynamic model. And, by casting light on how an opposition to regime critics has developed, my analysis seeks to inform and inspire those primarily concerned with the Internet’s “democratizing” effects.

This chapter focuses on the voluntary fifty-cent army for a few reasons. First, this strategy provides analytical continuity with the analysis of chapter 6 while avoiding the near-impossible task of assessing an exhaustive list of possible online groups. Second, it offers a perspective on public opinion in Chinese cyberspace that differs greatly from that which emerges from a static content analysis of state versus society or right versus left. And, finally, aside from a few accounts of cyber-nationalism and online commentators suggesting that pro-regime voices can be state-sponsored,21 few studies have systematically analyzed the dynamics of pro-regime expression online. Studying such a force thus may enable a better understanding of why China’s authoritarian regime still enjoys popular support.

THE VOLUNTARY FIFTY-CENT ARMY: IDENTITY, COMMUNITY, AND DISCOURSE

Online interactions tend to encourage the formation of relatively homogeneous user communities. Though seemingly a fluid and unreal space with anonymous users constantly logging in and out and commenting on diverse topics, online forums often allow users to develop closer online and sometimes offline ties, stronger mutual trust, and a shared group identity that differentiates them from others. Such netizen groups, with their distinctive language and behavioral codes, shared values and political inclinations, often promote discourse with a “communitarian subject constituted within, and bound by, an ethically integrated community.”22 Thus, homogeneous online communities become “information cocoons” in which a relatively stable discourse will be sustained and reinforced through frequent online and offline interactions.

But why would netizens take up the unpopular mission of defending the authoritarian regime and even name themselves after the notorious fifty-cent army? Are they truly voluntary in the first place? There are solid reasons to believe that members of the voluntary fifty-cent army are not state agents. First, they are not unthinking tools of the state; their opinions diverge from official discourse and are critical of the regime on a wide scope of issues, from censorship and policies regarding minorities to official ideology and discourse. For instance, they debate the merits and faults of current and past leaders, a practice discouraged by the state, and they frequently disparage the propaganda system as incompetent and corrupt. They even adopt the idioms and critiques of dissidents, such as referring to former premier Wen Jiabao as China’s “best actor.”23 Second, members of the voluntary fifty-cent army are often active on overseas, smaller-scale, or less popular boards and forums, which are not at the heart of the state’s efforts to control and shape public opinion. If they were actually state agents, it is likely that they would be active mainly on popular domestic platforms. Third, unlike the state-deployed Internet commentators who generally avoid arguing with netizens on controversial topics, the voluntary fifty-cent army has become adept at using creative online expressive tactics and more actively engages in online debates. Moreover, I also personally know several active voluntary fifty-cent army members who are clearly not state agents and who, to all appearances, are sincere in their beliefs. All these reasons suggest that at least some regime defenders are not paid state agents.

The very existence of the voluntary fifty-cent army was, in fact, an accidental discovery of my guerrilla ethnography.24 When exploring online forums, I found netizens demonstrating a strong sense of territory. I frequently observed adversarial comments like “Go back to the military boards where you can keep each other warm!” and “Go back to your angry youth home, Kdnet!” By following these cues, and noting the associations among users, expressive behavior patterns, and certain platforms, I located the home bases of the voluntary fifty-cent army, and these became my primary data collection sites. These sites included military-related discussion boards on NewSmth and Mitbbs, the military enthusiasts’ forums Cjdby and Sbanzu, the “Outlook” board of the popular forum Tianya, as well as the overseas Chinese forum Ccthere. Aside from Mitbbs and Ccthere, all these sites are domestic forums located inside China’s Great Firewall. Moreover, though they vary dramatically in popularity, all the selected forums attract stable traffic flows—even the smaller ones claim a simultaneous user population of one thousand or more during peak periods. As a result, even though this selection of sites is not representative of the full range of political discourse across the entire Chinese cyber-sphere, it is sufficient to study the voluntary fifty-cent army.

The Voluntary Fifty-Cent Army: The Formation of Group Identity

To understand why “innocent” netizens would associate with the fifty-cent army, it is important to examine how the group identity of the voluntary fifty-cent army has come into being. Largely a reaction to pervasive criticism and rumors targeting the regime, identification with the voluntary fifty-cent army is both externally imposed and actively chosen. In the first place, online antagonism, such as that seen in the labeling wars, provides the initial momentum for identity formation by imposing the fifty-cent army label on some netizens. Censorship and opinion-guiding efforts by the state often spark netizens’ fury toward a lurking fifty-cent army such that any voice supportive of the state comes to be viewed as a state agent regardless of any “accidental causalities.”25 Although many of those labeled fifty-cent army simply retreat or keep silent, some fight back. In this sense, many netizens become the voluntary fifty-cent army involuntarily: They fall into this camp because they are labeled fifty-cent army (bei wumao, 被五毛) by others who dislike their pro-government stance. The confrontation often further amplifies enmity, which in turn promotes the imagined threat of enemies and consolidates the voluntary fifty-cent army identity.

The external imposition of the fifty-cent army label has been complemented by the active construction of a group identity, thus promoting a voluntary acceptance of the label. Once labeled as a member of the fifty-cent army, some netizens somehow subvert the pejorative label and turn it into a badge of honor and superiority: They believe they are demeaned only because they are more patriotic and rational than their opponents. For instance, Zhang Shengjun, a professor of international politics at Beijing Normal University, explicitly links the fifty-cent army to the concept of patriotism by arguing that the label has become a “baton waved at all Chinese patriots.”26 It is not purely a coincidence that voluntary fifty-cent army members often evince nationalistic opinions. Nationalistic netizens view the West skeptically and tend to see the regime as playing a critical role in unifying and industrializing the nation. As a result, they are more likely to support the regime.

But the voluntary fifty-cent army is not just a group of cyber-nationalists. Members of the group claim that they emphasize evidence and logic over more emotional, nationalistic claims in debates. The association with rationality justifies acceptance of the group identity. The following example is telling. By pointing out the unequal growth rates of Han and non-Han populations (2.03 percent versus 15.88 percent, respectively) in China’s 2005 One-Percent Population Survey and its 2000 census, many nationalistic netizens argue that family planning regulations—which impose birth control on Han Chinese but not on ethnic minority groups—is tantamount to the “genocide” of Han Chinese. In response to this, one Ccthere user explained away Han versus non-Han disparities in population growth as a result of statistical error. Before his rebuttal, he added,

I have heard about the job of paid Internet commentators, which I have always wanted. But I don’t know who is in charge of recruiting. Since I have been longing for the job, let me try to explain this “genocide policy” by Tugong [土共, the “Bandit Communist Party”].27 Take it as my effort to clean up the mess for Tugong, and count it as my application for the Internet commentator position. So please feel free to forward. You may get a referral bonus.28

Claiming that scientific rationality distinguishes the voluntary fifty-cent army from other nationalist and far-left-wing groups who are commonly perceived as anti-West (and sometimes pro-regime).29 For them, what one argues for is an issue of standpoint (lichang wenti, 立场问题), and how one advances an argument is an issue of intelligence (zhishang wenti, 智商问题). The standpoint may be critical, but it must be backed with intelligence, or else it will only make one look like a fool.

The Tactics of the Voluntary Fifty-Cent Army

Taking on the identity of the voluntary fifty-cent army does not mean these netizens build online communities. Community-building occurs through a process similar to that of identity formation, and thus is driven by confrontations with netizens who disagree with each other and amicable interactions among those who are like-minded. Indeed, members of the voluntary fifty-cent army engage in a rich array of rhetorical games in their everyday online activities. Through such regular interactions, they consolidate their identity, build community, and sustain a pro-regime discourse. This section examines the interactive tactics that are employed by the voluntary fifty-cent army. These tactics share a playful quality, a nationalistic orientation, and most importantly, an emphasis on rationality.

Labeling Wars

Labeling refers to the practice of imposing a disgraceful label on opponents in online debates. Labeling wars provided the initial momentum for the formation of the voluntary fifty-cent army in that some of its members acquired the identity because they had been labeled as members of the state-sponsored fifty-cent army. The same mechanism continues to reinforce this identity in online debates. In addition, a labeling war is never unidirectional. If being labeled fifty-cent army helps a person to passively define who they are, labeling others, particularly enemies, constitutes a more active seeking of identity by defining who they are not. Members of the voluntary fifty-cent army use many labels to describe their opponents, including the “U.S. cents party” (meifen dang, 美分党; i.e., agents hired by the United States), the “dog food party” (gouliang dang, 狗粮党; i.e., those begging foreign powers for food like dogs), and the “road-leading party” (dailu dang, 带路党; i.e., those who lead the way for invaders). These counter-labels recast their accusers as aligning with foreign governments. Not all counter-labels are nationalistic, however. For instance, the labels of “elite” (jingying, 精英) and “public intellectual” (gongzhi, 公知) are often used by the voluntary fifty-cent army to demean pro-liberal intellectuals and media professionals.30 Such labels carry strong negative connotations that these groups are detached from the public, lack common sense and professional knowledge, and, most importantly, prioritize standpoint over logic and facts owing to ignorance or their attempts to manipulate public opinion. These labels further demonstrate that the voluntary fifty-cent army is not a group of run-of-the-mill nationalists. The use of diverse labels also reflects a variety of political inclinations among members of the voluntary fifty-cent army, with many emphasizing their national identity and others adopting a more class-oriented perspective.

Face-Slapping

Given the symbolic significance of face (mianzi, 面子), referring to reputation, in Chinese society, “face-slapping” (dalian, 打脸) is considered quite radical and directly confrontational. In online discussion, face-slapping is an effective way to impair an opponent’s reputation by challenging a point ruthlessly and pointing out logical errors, factual mistakes, or discrepancies. For instance, Internet regulation efforts by liberal democracies have often been cited as a way to “slap the face” of those advocating for Internet freedoms in China. The goal of the voluntary fifty-cent army is not to defend censorship, but rather to rebut those who fail to differentiate regulation from censorship and to criticize “road-leaders” for turning a blind eye to their masters’ “censorship” and highlighting Western hypocrisy.31

In many cases, face-slapping serves to defend the regime more directly. For instance, after the March 2010 Japanese earthquake, a Cjdby user explicitly stated, “Those claiming that earthquakes can be forecasted after the Wenchuan earthquake, I am here to slap your face!!!!”32 The post defended the regime by suggesting that many criticisms are unfounded and unfair. This same logic held when the “face” of the Southern Clique—a loose grouping of pro-liberal media outlets and professionals connected to the Southern Media Group and a long-imagined enemy of the voluntary fifty-cent army—was slapped over the same incident. When reports by the group appeared on forums praising the Japanese for being orderly and lauding its government for transparency, the voluntary fifty-cent army immediately countered with news about looting in earthquake-stricken areas and criticism of Tokyo Electric Power and the Japanese government.33 They argued that media outlets such as the Southern Clique held the Japanese and Chinese governments to different standards and attributed the Southern Clique’s critical portrayal of the Chinese state’s response to the Sichuan earthquake to its malicious, anti-regime intentions.

Cross-Talk

Unlike labeling wars and face-slapping, both of which require direct confrontation, cross-talk (xiangsheng, 相声) involves the collective ridicule of enemies. The popular linguistic art of Chinese cross-talk uses exaggeration, irony, or parody to highlight the illogical, laughable, or ridiculous nature of an opponent’s views. For instance, when China’s first aircraft carrier started its maiden sea trials in August 2011, one Ccthere user commented, “Ah, we don’t want a floating coffin. We want a star destroyer.”34 Fellow community members knew immediately that this comment was intended to poke fun at those who condemned China’s aircraft carrier as “a coffin floating on the sea.”35 Similarly, when voluntary fifty-cent army members on Mitbbs repeated slogans like “Heaven condemns the CCP” (tianmie zhonggong, 天灭中共)36 or “It is all because of the Three Gorges Dam”37 after earthquakes shook New York and Washington, DC, they were not condemning the Chinese Communist Party or blaming the Three Gorges Dam project, but practicing cross-talk.38 Such comments were intended to ridicule and parody the tendency of some netizens (and dissidents) to attribute all disasters to the Chinese Communist Party.

Fishing

“Fishing” (diaoyu, 钓鱼) is one of the most popular tactics of the voluntary fifty-cent army. Unlike phishing practices that attempt to obtain users’ sensitive information under the guise of trustworthy entities, fishing takes advantage of netizens’ tendency to believe what they want to believe by “hooking” them with fabricated information, thus revealing their gullibility or inherent biases. The game has four stages: (1) bait preparation, which is the fabrication of a message as bait; (2) bait spreading, which involves posting the message to targeted platforms; (3) hooking, which involves collecting evidence that netizens are spreading the false information; and (4) celebration, which consists of laughing at those who were gullible enough to fall for the false message.

A classic case of fishing started at sbanzu.com, a military forum in which voluntary fifty-cent army members concentrate. Mainly to demonstrate the superficiality, ignorance, and bad intentions of Kuomintang fans (guofen, 果粉 or 国粉) and the “truth discovery party” (zhenxiang dang, 真相党),39 the user “Muhaogu” forged a handwritten receipt by Mao Zedong (figure 7.1). This “receipt” states that Mao had received 350 million gold rubles from the Comintern (an international organization advocating world communism). The document contains historical anachronisms and handwriting errors and also explicitly states at the bottom that it was “made by the Pollen Institute and specially designed for the Truth Discovery Party.”40 However, when posted on Kdnet, one of the perceived bases of Kuomintang fans and members of the “truth discovery party,” it was taken by many netizens to be a piece of newfound “truth” about the Chinese Communist Party’s inglorious history. The highlight of the story for “Muhaogu” was that a Kdnet user and student of Chinese Communist Party history cited the document in her Master’s thesis and was expelled from her program as a result. This was an unexpected and delectable “fish” for many in the voluntary fifty-cent army. Catching such a “fish” so easily further convinces the voluntary fifty-cent army that many of their opponents are ignorant and intellectually incurious.

FIGURE 7.1 Forged receipt by Mao Zedong to the Comintern. Image courtesy of Mr. Muhaogu.

A more influential case of fishing made it into China’s print media. Mimicking a report on Huang Wanli, a hydrologist known for his opposition to the Three Gorges Dam project, a Mitbbs user fabricated a story of an imaginary environmental scientist called Zhang Shimai who had proposed a theory that high-speed trains will cause massive geological disasters.41 Two key concepts defined at length in the fabricated theory, the “Charles Chef Force” and the “Stephen King Effects,” were actually named after two popular Mitbbs users, “xiaxie” and “StephenKing.” Widely reproduced online, the article hooked many unsuspecting readers despite efforts by netizens and the Chinese Academy of Sciences to debunk the story.42 More astonishingly, the nonexistent Professor Zhang was “quoted” by China Business News (diyi caijing ribao, 第一财经日报) after a high-speed train accident on July 23, 2011.43 The newspaper was forced to make an apology when netizens started to “slap its face” by commenting on the report. However, even after that, Zhang continued to be quoted by a Xinhua News Agency reporter in her microblog.44 Such events only serve to feed the deeply held belief among the voluntary fifty-cent army that some media groups are either unprofessional or harbor ulterior motives that blind them from simple facts.45

Positive Mobilization

Like other online activists, the voluntary fifty-cent army sometimes mobilizes shared beliefs, values, or emotions directly. For instance, as mentioned in chapter 4, a serial entitled “The Glorious Past of the Little White Bunny”—the playful narrative praising the Communist Party for unifying and building the nation—is very popular among the voluntary fifty-cent army. On Cjdby alone, the serial has attracted over 4.5 million views and 14,000 replies.46 The following alternative lyrics by a Cjdby user to the “Ode to the Motherland,” the song sung at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics, serves as another good example of positive mobilization:47

ODE TO THE MOTHERLAND (TRANSLATED BY THE AUTHOR WITH AUTHOR’S NOTES IN PARENTHESES)

The Flag of Five Stars is fluttering in the wind (The Flag of Five Stars is the Chinese national flag and is clearly a symbol of nationalism),

The Song of CNMD is so sound (The abbreviation “CMND,” which stands for “Chinese National Missile Defense,” is a pun on the phrase “fuck your mother”),

We are singing for our “black-belle” TG (“ ‘Black-belle’ TG” is jargon used by military enthusiasts meaning “evil Communist Party” and is an affectionate nickname the voluntary fifty-cent army often uses to refer to the regime),

And the Fucking Two Holes is even more shameless and rogue (“Fucking Two Holes” is again an obscene pun, in this instance referring to the first Chinese stealth fighter, the J-20).

We are clean and honest,

We are nice and kindhearted,

The white bunny and the panda are the role models of our kind (These lines project an innocent and “cute” image of China and the regime),

How many times we’ve being looked down upon we cannot count,

And today we finally can be proud and unbridled (These lines clearly attempt to evoke nationalism through past memories of humiliation),

We love river crabs (As discussed in chapter 4, the river crab symbolizes state censorship; this, this line demonstrates that the voluntary fifty-cent army supports the regime),

We love keeping accounts (jizhang, 记账; some members of the voluntary fifty-cent army claim that they are “keeping accounts,” or keeping a record of enemies’ misdeeds, to ensure payback in the future),

Whoever owes us money and refuses to pay back will be eliminated! Long live our motherland, our mighty and powerful motherland! (Although this is not an alternative lyric, it demonstrates blunt nationalist sentiment.)

These alternative lyrics demonstrate an ostensible nationalistic stance and support for the regime among the voluntary fifty-cent army. The mixture of national symbols, combined with elements of a particular military forum’s subculture (including the profanity), appealed to fellow community members and made the post very popular.48 Posted right after China’s stealth fighter J-20 made its first public flight in January 2011, the post attracted more than one thousand replies within two weeks, most echoing the message of and lauding the original post.

Other popular tactics among the voluntary fifty-cent army include onlooking (weiguan, 围观), playing undercover (wujiandao, 无间道), and keeping accounts (jizhang, 记账). Onlooking refers to large crowds surrounding and watching spectacles. Although often deployed by regime critics to demonstrate public opinion and question the regime,49 this tactic is also used by the voluntary fifty-cent army to bully their opponents. By bombarding a target with repeated replies saying “onlooking” or “onlooking, too,” they signal to other netizens that the target is voicing an unpopular or even absurd opinion.50 In “playing undercover,” members of the voluntary fifty-cent army hide their true opinions and support the opposite side in an exaggerated and parodied fashion, recasting opponents as unpersuasive and untrustworthy. Keeping accounts refers to keeping a record of what perceived enemies have said or done as evidence of their bad deeds or inconsistency. For instance, a Ccthere user compiled a collection of BBC reports about the Chinese Internet over eight years in which one photo was repeatedly used but interpreted differently. In its earliest appearance in 2000, the photo was used as an illustration of “authorities wary of the web.” But, in 2008, right before the Beijing Olympics, the photo was interpreted as “China enhancing its surveillance of Olympic guests.”51

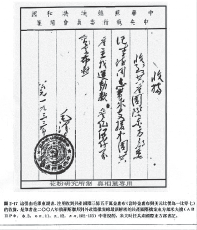

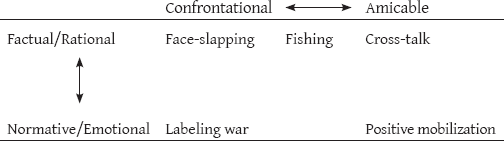

Not all these expressive tactics are exclusively deployed by the voluntary fifty-cent army. Some, such as labeling wars, onlooking, and positive mobilization, are common among netizens generally. Others, such as face-slapping, fishing, and keeping accounts, are more specific to the voluntary fifty-cent army. However, these rhetorical games all help define the group identity and share certain features. In particular, they vary along two important dimensions: the degree of confrontation and the type of persuasive power (table 7.1). In terms of confrontation, some games rely primarily on facts and reasoning to persuade others or to mock opponents, whereas others resort to emotional and normative appeals. The more distinctive rhetorical tactics employed by the voluntary fifty-cent army—face-slapping, fishing, and keeping accounts—are used to demonstrate that its members prioritize logic and factual evidence in debates, in contrast to other cyber-nationalists and regime supporters. In terms of persuasive power, some games involve direct attacks on opposing opinions, whereas others are more like playful ripostes among voluntary fifty-cent army members themselves, and still others fall somewhere in between. Through antagonistic interactions with other netizens, the voluntary fifty-cent army shapes and defines its group identity, demonstrating that its members are unified in their opposition to a perceived set of regime critics or foreign-agent “enemies.” Mutual cooperation and more amicable interactions within the group further strengthen group identity by reinforcing shared values and behavioral codes.

TABLE 7.1 Categorizing the Rhetorical Tools of the Voluntary Fifty-Cent Army

The categorization in table 7.1 is not definitive, but rather contextualized. On one hand, the factual/rational and normative/emotional divide exists but is far from clear-cut. For instance, in both of the positive mobilization cases discussed, readers’ attention was directed toward a series of historical events imbued with nationalistic sentiment. In fact, nationalism and rationality serve as major forces in defining the identity of the voluntary fifty-cent army. Nationalism provides the normative imperative: to defend the nation against online sabotage by enemies from within and without. Rationality, however, justifies the group’s accusation that much online criticism is unfounded or biased, thus reinforcing the belief among its members that they are enlightening netizens who are otherwise deceived, ill informed, or unreflective.52 Thus, both factual/rational and normative/emotional persuasive techniques provides the voluntary fifty-cent army with a sense of fulfillment and superiority.

On the other hand, the antagonism inherent in these tactics largely depends on who is using them and the context in which they are used. For instance, when deployed in the presence of other voluntary fifty-cent army members and supportive netizens, tactics like cross-talk, which involve subtle satire, are often echoed and appreciated. When deployed in the presence of opposing netizens, they frequently escalate into direct confrontation. Similarly, the degree of antagonism can vary at each stage in a multi-stage battle depending on changes in context or participants. Take fishing as an example. While bait preparation and celebration generally consist of amicable interactions within the voluntary fifty-cent army group, hooking often involves direct confrontation to humiliate the hooked (often on perceived enemy sites, which are seen as “fish ponds” by the voluntary fifty-cent army). In fact, many voluntary fifty-cent army members refer to this step as face-slapping.

Despite the variation in degree of antagonism and pattern of persuasive power, these rhetorical tactics consolidate the collective experiences of the voluntary fifty-cent army into a cohesive group identity, strengthening community ties, and producing a pro-regime discourse. The fishing tactic discussed earlier in this chapter, which involves multiple community members at different stages, is a perfect example. Although it takes only one creative member to devise the bait, others may contribute by offering comments and suggestions or by producing adaptations of the message or even derivative stories.53 Community members also play a larger role in spreading the bait, especially initially.54 “Setting a hook” often involves collective confrontation with those who get hooked, thus promoting group identity through solidarity against a common enemy. Celebration enhances the collective imagination of a common enemy; against a “them,” members of the voluntary fifty-cent army actively project an image of an “us.” Moreover, by employing shared behavioral codes and championing similar values and beliefs, the voluntary fifty-cent army has effectively established independent online colonies, or public sphericules, with a fairly stable regime-defending discourse.

The rhetorical games can backfire, though. Fishing, for instance, can effectively discredit opponents, but the tactic is a double-edged sword. To counter criticism of China’s aircraft carrier project, a Mitbbs user wrote a post titled “For a country without human rights, what’s the point of building aircraft carriers?”55 In the post, the author states,

Recently, in one of its northern cities, a power has been speeding up construction of an aircraft carrier, which has symbolic significance.

…

However, under the glossy surface of being an Olympic Games host and aircraft carrier owner is a different picture—at the same time the carrier is being built, a growing number of “mass incidents” [quntixing shijian, 群体性事件, referring to public protests and other forms of collective dissent] are imposing huge pressure on the country’s stability maintenance apparatus. They have introduced strict control over the Internet, manipulated public opinion, deployed legions of police to disperse assemblies, and are ready to arrest netizens spreading “inharmonious” information.

Canada’s Vancouver Sun commented on [August] 10 that the society is “sick.” French commentator Agnes Poirier even told the BBC that this country remained one of the most “unequal societies” [in Europe].

Though the user confessed that he intended to mock Great Britain, both those critical and those supportive of the regime took the bait. This example reveals the dilemma faced by the voluntary fifty-cent army: When people prove unable or unwilling to recognize the barbs in the bait, hooking a fish can turn into feeding a fish and involuntarily add to the volume of rumors and criticism that the voluntary fifty-cent army is trying to fight.56

The Reach and Influence of the Voluntary Fifty-Cent Army

Owing to the subjectivity of its members’ identities and the fluidity of cyberspace, it is impossible to estimate the size of the voluntary fifty-cent army. However, there are indicators of the reach of the group, which suggest that the voluntary fifty-cent army has become a significant force in online expression.

Although representing a small portion of netizens, the voluntary fifty-cent army has firmly established itself in cyberspace, with certain platforms such as military forums tending to serve as initial bases. This is by no means an accident, as these forums often attract nationalistic netizens with a realistic view of international politics. As nationalists, they appreciate the regime’s role in unifying, industrializing, and strengthening the nation. For them, despite all its problems, the current regime contrasts well with the pre-1949 Kuomintang regime that not only failed to establish domestic order, but also failed to protect China from external threats. They are convinced that the nation is on the right track and that maintaining stability is necessary. Their realist or even hawkish inclination makes them susceptible to the counter-espionage framing that imagines domestic and foreign regime critics as national enemies engineering online expression to sabotage China’s revival. As these like-minded netizens naturally gravitate to military forums, they gradually turn these platforms into virtual colonies in which they intensify their interactions with each other and exchange ideas, which in turn further shapes and consolidates their identity.

The voluntary fifty-cent army has occupied not only small-scale forums that attract nationalistic netizens or military enthusiasts, but also popular boards on major forums such as Mitbbs, NewSmth, and Tianya. Tianya is the largest online forum in China, attracting millions of visitors daily, whereas Mitbbs and NewSmth are the most popular student forums, each with more than thirty thousand simultaneous users.57 Not all users identify with the voluntary fifty-cent army, but the group has gained traction on these platforms, demonstrating its capacity to reach a wide audience, as netizens “vote” with their attention and continue to visit platforms where they are prominent.58 How the “Military” board has replaced “ChinaNews” as the most popular board on Mittbbs is a good example here. Before 2008, most netizens frequented “ChinaNews” to discuss Chinese politics, whereas the “Military” board attracted only military enthusiasts. But a series of events in 2008—the Lhasa riot, the Sichuan earthquake, and the Beijing Olympics—triggered a mass exodus from “ChinaNews” as users became dissatisfied with the anti-regime orientation that dominated the board. They turned to “Military,” where the voluntary fifty-cent army is based, for more “neutral” and more positive discussions of China. Since then, the “Military” board has often attracted ten times the traffic of “ChinaNews.”59 This shift reveals the growing influence of the voluntary fifty-cent army in online expression.

The influence of the voluntary fifty-cent army is not limited to the isolated virtual colonies they occupy. As a reaction to what they feel are unreflective criticisms of the regime, its members confront opponents both at their bases and on “battlefields” where they are not dominant. Such battlefields include other forums, blogs, and more recently, the Twitter-like Weibo. For instance, the concentration of voluntary fifty-cent army members on Tianya’s “Outlook” board does not prevent some members from entering debates on “Free,” the second-most popular board of the forum. Through labeling wars, cross-talk, and fishing, they try to exert influence beyond the locations they dominate.

The voluntary fifty-cent army has also built deeper and broader ties beyond their base platforms. Many of its members have established close contact using QQ or WeChat groups and have even developed real-life friendships with each other.60 These ties expand their reach and also link members of the voluntary fifty-cent army together. In addition, cross-community connections are established, linking relatively isolated voluntary fifty-cent army communities together. Just as like-minded websites cross-link more so than differently minded websites,61 voluntary fifty-cent army members based across different sites weave connections among the various sites they frequent. For instance, on NewSmth’s military boards, one can often find posts from Mitbbs’s “Military” board, Ccthere, and Cjdby, or Weibo entries from other voluntary fifty-cent army comrades. Fishing initiatives from Mitbbs may inspire similar ones on NewSmth.62 Some netizens even consciously advocate an alliance of communities that share similar political inclinations and face a common enemy. A Ccthere user explicitly argued that the voluntary fifty-cent army should support WYZX乌有之乡 (wyzxsx.com, an ultra-left website) against the common enemy of “universalists” (pushi pai, 普世派).63 Forums such as April Media (siyue chuanmei, 四月传媒; formerly Anti-CNN.com) and more serious news platforms such as the Observer (guanchazhe, 观察者; guancha.cn) show that the voluntary fifty-cent army, which has largely been reactive, may be growing into a more self-conscious group with a clearly defined mission to execute.64 Through this transition, at least some of its members have turned into political activists who strive to disseminate their political beliefs online.

In fact, the voluntary fifty-cent army has grown from an online phenomenon into a group with political momentum. For instance, after the Taiwanese election in early 2016, many Chinese netizens flooded the Facebook page of President-Elect Tsai Ing-wen to defend the “One China” principle, many of whom claimed to be members of the voluntary fifty-cent army.65 Though not all such self-appointed members likely fit in the definition of a voluntary fifty-cent army member outlined in this chapter, this case nonetheless demonstrates the political influence of the group.

As a political force, the voluntary fifty-cent army is now also recognized by the Party-state. On October 15, 2014, at the highly prominent and symbolic Forum on Literature and Art in Beijing, President Xi Jinping openly praised two “online writers”—Zhou Xiaoping and Hua Qianfang—who are viewed as representatives of the voluntary fifty-cent army.66 Since not one of the many more influential cyber-celebrities or public intellectuals was invited to the event, the state’s promotion of Zhou and Hua was clearly intended to bring the voluntary fifty-cent army under its banner.67 However, this move backfired among both the voluntary fifty-cent army and ordinary netizens. For the voluntary fifty-cent army, Zhou and Hua are not considered their true representatives: They are considered to be overtly pro-regime, and their comments tend to be logically and factually weak. For ordinary netizens, the association with the state immediately turned the voluntary fifty-cent army from a relatively neutral group into the state’s convenient mouthpiece.

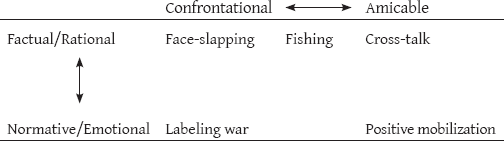

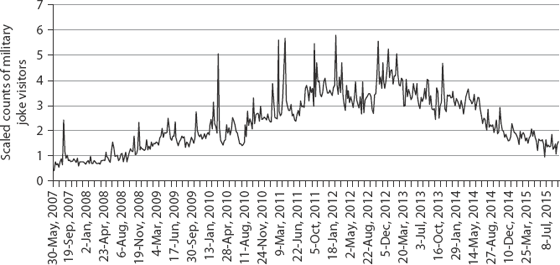

Indeed, the popularity and influence of the voluntary fifty-cent army appears to fluctuate over time depending on factors such as state behavior. Take NewSmth’s “MilitaryJoke” board as an example. As figure 7.2 shows, the board’s influence grew significantly from 2007 to 2011, after which it suffered a temporary stagnation before starting to decline steadily after a brief period of revival in late 2012. The changes in the trend correspond well with the leadership succession in China. The period of stagnation overlapped with the power struggle before the Chinese Communist Party’s Eighteenth National Congress, and the continuous decline started quickly after Xi Jinping assumed power—both time periods that witnessed tightened state control over online expression. Since “MilitaryJoke” is only a small board and generally features pro-regime expression, the decline was unlikely the result of direct state censorship. Instead, it may well be that enhanced state control delegitimized the group, making it less appealing among ordinary netizens.

FIGURE 7.2 Weekly military joke visits in relation to NewSmth average.

Source: newsmth.net.

CONCLUSION

Cyberspace is not a monolithic medium. Instead, it consists of fragmented fields that serve either as frontiers at which opponents meet or colonies occupied by certain communities. The analysis of the voluntary fifty-cent army in this chapter details how group identity has been shaped through repeated rhetorical interactions with both opposing netizens and fellow community members. Such interactions have turned some online platforms into voluntary fifty-cent army bases in which a particular pro-regime discourse is produced and reproduced.

Though they represent just a small portion of netizens, the voluntary fifty-cent army influences public opinion in significant ways. An experimental study with Facebook users, for example, found evidence of emotion contagion on a massive scale; that is, emotions expressed by others influence our own.68 Other researchers have found that social consensus can effectively be influenced or even reversed by a minority of committed agents who “consistently proselytize the opposing opinion and are immune to influence.”69 Here, members of the voluntary fifty-cent army compose just such a “committed minority” in Chinese cyberspace. Their relatively neutral stance, calls for nationalism, emphasis on facts and rationality, as well as their sense of humor, all make them more effective in persuading netizens than state agents. In fact, a Ccthere user openly claimed that given the incompetence of state propaganda bodies, the voluntary fifty-cent army has started to play a larger role in maintaining the regime’s stability.70

Rather than denying the efforts of researchers, observers, and activists to “push China’s limits on the web,” the chapter aims to highlight the complicity and plurality of opinions on the Internet and the subsequent implications.71 Such a perspective helps take our understanding of cyberpolitics in China beyond the state-versus-society models—subaltern norms versus state norms, an expanding public sphere versus state censorship, a rising civil society versus an authoritarian regime, and empowered social actors versus state suppression—to one that recognizes conflict among social actors themselves.72 In this way, it contributes to the authoritarian resilience literature by highlighting that in addition to variables such as state capacity and adaptability,73 groups such as the voluntary fifty-cent army help stabilize the regime, not so much by legitimizing it, but by undermining the moral and factual grounds of regime challengers.