Some stories are hard to see, generally because the clues are hidden or disguised. By accident, or on purpose. Other stories hit you in the face. Like Watergate, for instance.

Five guys in business suits, speaking only Spanish, wearing dark glasses and surgical gloves, with crisp new hundred-dollar bills in their pockets, and carrying tear-gas fountain pens, flashlights, cameras, and walkie-talkies, just after midnight in the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee (DNC).

The best journalists in the world could be forgiven for not realizing that this was the opening act of the scandalous political melodrama—unparalleled in American history—which would end up with the resignation of a disgraced president and the jailing of more than forty people, including the Attorney General of the United States, the White House chief of staff, the White House counsel, and the president’s chief domestic adviser.

But you would have to be Richard Nixon himself to say this was not a story.

The Washington Post got off to a running head start on the story, early on the morning of June 17, 1972, thanks to Joe Califano, once special assistant to President Johnson, then counsel to both the Democratic Party and The Washington Post. Califano was Edward Bennett Williams’s law partner.

Califano called Howard Simons, the Post’s managing editor, that morning to tell him that five guys had broken into the DNC a few hours earlier and were about to be arraigned. I was in West Virginia for the weekend, where the telephone didn’t work, but Simons called Harry Rosenfeld, the Metro editor, and Rosenfeld called Barry Sussman, the city editor. Sussman, still in bed, called two reporters, finally getting to someone who could find out what the hell was going on. (It flows downhill at newspapers, too.) The two reporters, chosen by Rosenfeld and Sussman, were local reporters, for this was a local story, involving the commonest of local crimes—breaking and entering.

They were Al Lewis, the prototypical police reporter, who had loved cops more than civilians for almost fifty years, and Bob Woodward, a former Navy lieutenant and one of the new kids on the staff, who had impressed everyone with his skill at finding stories wherever we sent him.

Lewis arrived at the scene of the break-in in the company of the acting chief of police, sailing past other reporters who had been stopped by the cops. He spent all day behind the police lines, calling in to the city desk regularly with all the vital statistics. Woodward covered the arraignment. He was sitting in the front row (where else?) where he heard James McCord, Jr., whisper, “CIA,” when the arraigning officer asked him what kind of a “retired government worker” he was.

Bingo!

No three letters in the English language, arranged in that particular order, and spoken in similar circumstances, can tighten a good reporter’s sphincter faster than C-I-A.

By day’s end, and on into the night at police headquarters after the final deadline had passed, ten reporters were working on different pieces of the story. On his regular shift at Night Police, after three in the morning, reporter Gene Bachinski was given a look at some of the stuff taken from the pockets of the arrested men. Including address books, and in two of these he found the name of Howard Hunt; along with the notations: “W.H.” and “W. House.”

Bingo!

Just the recollection of that discovery makes my heart beat faster, more than two decades later.

Carl Bernstein, the long-haired, guitar-playing Peck’s Bad Boy of the Metro staff, spent most of Saturday sniffing around the story’s perimeter as all good reporters do, and soon was told to “work the phones.” We needed help in Miami, where all the defendants came from, and it turned out we already had a correspondent there: Kirk. Scharfenberg, another Metro reporter, who had spelled our tireless White House correspondent, Carroll Kilpatrick, on the Nixon watch in Key Biscayne.

The next morning Woodward went looking for the mysterious Howard Hunt, and started by calling the “W. House,” and asking to be connected with him. An extension rang and rang, and rang. No answer. And a wonderful White House telephone operator (all White House telephone operators, by definition, are wonderful) told Woodward to wait, maybe Mr. Hunt was in Mr. Colson’s office.

Bingo!

Another rush of adrenaline, with that word “Colson,” the highprofile hatchetman assistant to Nixon.

Hunt wasn’t there, but Woodward and everyone else wondered why he might have been there, when Charles Colson’s secretary told him to try Hunt at Robert R. Mullen & Co., a PR firm. Hunt was there, and Woodward asked him how come his name was in the address books of two burglars arrested at Democratic headquarters.

There was a long, long pause. And then only, “Good God.”

Bingo!

Kilpatrick spotted McCord’s picture in Sunday’s paper, and immediately recognized him as someone who worked for the president’s reelection committee. CRP, for Committee to Re-elect the President, as the Republicans called it, or CREEP, as it came to be known around town.

Bingo!

In less than forty-eight hours, we had traced what the Republicans were calling a “third-rate burglary” into the White House, and into the very heart of the effort to win Richard Nixon a second term. We didn’t know it yet, but we were out front, never to be headed, in the story of our generation, the story that put us all on the map.

Now, twenty years after the fact, it is far easier to re-create this fabulous story than it was to report this fabulous story . . . thanks to the incredibly detailed record which emerged slowly from the dark:

• Transcripts of tapes of more than 4,000 hours of conversations involving all the key characters . . . Nixon, Mitchell, Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Dean, Colson, et al.

• The voluminous record of hearings held by the spectacular Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, known as the Senate Watergate Committee, or the Ervin Committee, for its chairman, Senator Sam Ervin, the colorful North Carolina Democrat. Eighty-three days of testimony (most of it televised) from thirty-three witnesses.

• The record of the House Judiciary Committee’s hearings on the impeachment of the president.

• The record of all the trials, which led to more than 40 guilty pleas or convictions.

But for six weeks after the break-in, we were flailing, searching everywhere for any information that might shed any light, unaware that we were up against a massive cover-up being orchestrated by the White House. We were picking at the story, knowing it was there but unable to describe what “it” was, finding what looked like pieces of the puzzle but unable to see where—or even if—these pieces fit. For instance, we soon learned that burglar Frank Sturgis had another name, Frank Fiorini—the same Frank Fiorini I had met some months before, with Tony’s much older half brother, Gifford Pinchot.

Giff was a genuine original, tall, gaunt, and handsome, about sixty years old and a bachelor, living in Miami then, having been kicked out of Castro’s Cuba. In Havana, he had lived with a Cuban woman, known only as La China, taught rhumba dancing, managed a couple of Cuban lightweight boxers, and worked as some kind of an engineer on the side. When I was in New York late one afternoon in 1971, he had asked me to meet him and a friend in an East Side bar for a drink. He thought I’d be interested. Fiorini was tall and well muscled, with oily, wavy black hair, and ham hands. He looked and talked like a hood, as he went about trying to persuade me and “Pinchot, here” to come up with the wherewithal for 1,500 gallons of Diesel fuel, so he could take a boat to Cuba, make trouble for a few days, and get out. I felt sorry for Giff, because his hatred of Castro was clearly going to be money in Fiorini’s pocket.

After we’d identified Fiorini as Sturgis, I tried to see him for weeks after the Watergate break-in—through his lawyer, and through federal marshals—without success.

Bernstein finally broke into the clear with a story on August 1 about the origins of the money found on the Watergate burglars when they were arrested. It was a critically important piece of information. “Cherchez la femme” is good advice for investigative reporters. “Follow the money” is even better advice. Carl understood that instinctively, and persuaded us to send him to Miami to talk to the prosecutor there who had started his own Watergate investigation. He found Martin Dardis, an investigator who had traced the serial numbers on the crisp new hundred-dollar bills to the Republic National Bank of Miami. Did any of the burglars have a bank account there?

Damned if one of them, Bernard Barker, didn’t have two. Dardis had Barker’s telephone records and bank accounts subpoenaed, and found five cashier’s checks, totaling $114,000, which had been deposited in one account in April 1972. Four of those checks, totaling $89,000, had been issued by a Mexican bank to a Mexican lawyer. The fifth check, for $25,000, was even more interesting. Dardis showed Bernstein that it came from a man named Kenneth H. Dahlberg. Woodward, in Washington, found two Kenneth H. Dahlbergs, one in Boca Raton and one in Minneapolis. A little more work and we found they were one and the same man. And a few minutes later Woodward had him on the phone in Minneapolis. He knew nothing about the $25,000 check, he told Woodward, but as a fund-raiser for Nixon he turned over all the funds he raised “to the committee.” And he hung up.

Another Bingo!

A fund-raiser for the President of the United States? What’s he doing putting money in a burglar’s bank account?

A few minutes later, Dahlberg called back, to verify that Woodward was in fact a Post reporter, he said, and was more forthcoming. As a fund-raiser he had accumulated a lot of cash, and in Florida, had converted that cash to a cashier’s check. Dahlberg told Woodward he gave the checks to Maurice Stans, CRP’s finance chairman. And he had no idea how any of the checks ended up in Barker’s bank account. *

Now we had the burglar’s money traced directly to CRP.

It was three months after the “third-rate burglary” (and less than six weeks before the election). The Republican denials and counterattacks were getting louder every day, and we knew they were lying. Nothing kept us more committed to this story than our knowledge—not suspicion, not wonder, but knowledge—that they were lying.

Woodward and Bernstein got hold of a copy of the CRP telephone directory and address book, and started calling CRP employees one by one—always after work, and often five or six times.

Soon they learned that at least some of the people who worked for CRP were scared. Some were asking to be interviewed by the FBI, without a CRP lawyer taking notes. One of the CRP employees they talked to was Hugh Sloan, the committee’s treasurer, and suddenly in September, as city editor Barry Sussman remembers, Sloan “became helpful.” By now we were beginning to obsess on the Watergate story. Other newspapers were breaking new ground occasionally, notably the Los Angeles Times. But the Post had the story by the throat, and the story had the town by the throat. Katharine Graham was in and out of the city room two or three times a day, looking for a “fix” on each day’s story. Most nights many of us would get telephone calls from friends in and out of government, unable to wait for the first edition to discover the latest development.

One morning after a particularly good story, attorney and dean of Washington insiders Clark Clifford, then at the height of his power and influence, called me, and in that dramatic, triplebreasted basso profundo of his spoke for much of Washington: “Mr. Bradlee, I would like to tell you something. I woke up this morning, put on my bathrobe and my slippers, went downstairs slowly, opened the front door carefully, and there it was. The sun was already shining. It was going to be a beautiful day. And I looked up to the heavens, and said, ‘Thank God for The Washington Post.’”

At first the White House counterattacks had tried to laugh off the Watergate break-in as a third-rate burglary, and dismissed newspaper interest as “just politics.” Kansas Senator Bob Dole, then chairman of the Republican National Committee, played the role of lead pit bull, accusing the Post of being Democratic candidate George McGovern’s surrogate in his challenge of President Nixon. Ron Ziegler, the White House press secretary, was making the evening news regularly to deny everything, expressing his “horror” at the “shoddy journalism” being practiced by the Post. (Clark MacGregor, the former Minnesota congressman, soon to succeed Mitchell as chairman of CRP, grew more and more critical, even one night when his daughter Laurie was spending the night at our house, as a friend of one of my stepchildren.)

John Mitchell, Nixon’s campaign manager at CRP, had weighed in with his criticism early in a uniquely vulgar and sexist way. On September 29—at 11:30 P.M.—Bernstein telephoned him for comment on a story that he had controlled a “secret fund” when he was Attorney General. Bernstein started reading out the story, when Mitchell exploded:

“All that crap you’re putting in the paper. It’s all been denied. Katie Graham’s going to get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published. Good Christ! That’s the most sickening thing I’ve ever heard. . . . You fellows got a great ball game. As soon as you’re through paying Ed Williams and the rest of those fellows, we’re going to do a little story on all of you.”*

Secretary of Commerce Pete Peterson, one of the few Nixon cabinet members who stayed friends with any of us, kept telling us that we were underestimating how much “they” hated us, were determined to do us in. We had no idea what they felt was their range of options. TV licenses? IRS audits? Wiretapping?

As the former Attorney General’s “tit in the wringer” quote resounded through the halls of Washington, we were already working on a story about Donald Segretti, a young California lawyer, first discovered by the FBI as agents went through Howard Hunt’s subpoenaed telephone records. A week after the Watergate breakin, the Feds realized that Hunt and Segretti were in some kind of business together, but they had put Segretti on a back burner when they couldn’t tie him to the Watergate break-in itself. Not Woodward and Bernstein. They didn’t have a back burner.

Woodward learned more about Donald Segretti from his “friend” who was known in the city room to have quite extraordinary sources. This friend was the soon-to-be legendary “Deep Throat.” Managing editor Howard Simons christened Woodward’s source “Deep Throat.” “Deep” surely from “deep background,” the terms on which he gave Woodward all information, and “Deep Throat” probably because that was the title of the year’s most successful pornographic movie, starring the awesome sodomist Linda Lovelace.

In the middle of September, Woodward read Deep Throat the draft of a story saying that federal investigators “had received information from Nixon campaign workers that high officials of the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP) had been involved in the funding of the Watergate operation.” Deep Throat told Woodward the story was “too soft,” adding, “you can go much stronger.”

The next day Deep Throat offered up Jeb Stuart Magruder, deputy campaign director of CRP, and Bart Porter (Herbert L.), scheduling director of CRP, “both deeply involved in Watergate,” he said, and confirmed that they had received at least $50,000 in dirty trick money from the safe of former Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans, now the finance chairman of the president’s reelection campaign. Woodward was told he could be damn sure the money had not been used for legitimate purposes. That was fact, not allegation, Deep Throat said.

In late September, Bernstein took a call from an anonymous male, who described himself only as a government lawyer. He told Bernstein about an organized campaign of political sabotage and spying against the Democrats, and suggested he call Alex Shipley, then an assistant attorney general of Tennessee, for the details. Shipley told Bernstein that he had been in the Army with Segretti, and when he got out, Segretti tried to recruit him to join the sabotage effort. Woodward and Bernstein managed to get copies of Segretti’s credit card records, and they confirmed that Segretti had been traveling the nation, spending a day or two in cities where the Democratic primaries would be held.

At the end of September, Clark MacGregor, campaign director at CRP, squeezed the pressure bar a bit by “demanding” an appointment with Katharine and me. With exaggerated emphasis, he would say only that the subject was “extremely important,” and we set it up for the morning of the 29th. By accident I had bumped into him the afternoon before, and he had started whining to me about Woodward and Bernstein “harassing” secretaries.

An hour before our appointment, MacGregor’s secretary called to say that he would be unable to keep it. She told me MacGregor felt he “had substantially accomplished his mission” during our conversation, according to a memorandum of conversation I dictated.

I asked her to tell him it had not accomplished anything, and she put him on. I asked him which secretaries were claiming what had been done to them by whom. (It would turn out that only Bernstein was being accused of harassment above and beyond the call of duty.) According to MacGregor, Sally Harmony, a secretary at CRP, had gone home sick one afternoon, and Bernstein learned about it, and went to her apartment, “and repeatedly tried to get in.” Another secretary had consistently found Bernstein waiting for her at her apartment door. Still another had been telephoned so often by Bernstein that she had been forced to move out and go live with her parents.

Bernstein had “repeatedly suggested lunch, cocktails, and so forth” to a secretary to Justice Rehnquist, again according to MacGregor.

I told him, “That’s the nicest thing I’ve heard about either one of them in years,” then murmured something about a raise for the boys, and hung up.

On October 9, Woodward and Deep Throat had their longest meeting ever, and one of their most productive.

“There is a way to untie the Watergate knot,” Deep Throat started out. “. . . everything points in the direction of what was called ‘Offensive Security. . . .’ Remember, you don’t do 1,500 interviews [with the FBI] and not have something on your hands other than a single break-in.”

“Who was involved?” Woodward asked.

“Only the President and Mitchell know,” came the ominous answer, without elaboration.

“That guy [Attorney General Mitchell] definitely learned some things in those ten days after Watergate. He was just sick, and everyone was saying that he was ruined because of what his people did, especially Mardian [political coordinator at CRP] and LaRue [Deputy Director, CRP], and what happened at the White House.

“And Mitchell said, ‘If this all comes out, it could ruin the administration. I mean, ruin it.’

“They were playing games, all over the map . . . in Illinois, New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, California, Texas, Florida, and the District of Columbia,” Deep Throat continued.

“What about Howard Hunt and leak-plugging?” Woodward asked.

“That operation was not only to check leaks to the papers but often to manufacture items for the press. It was a Colson-Hunt operation. Recipients include all of you guys—Jack Anderson, Evans and Novak, the Post, the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune. The business of Eagleton’s drunk-driving record or his health records, I understand, involves the White House and Hunt somehow.” (McGovern had dumped his vice-presidential candidate, Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, after reports surfaced in the press that Eagleton had been treated for clinical depression.)

A Letter to the Editor, which had appeared in William Loeb’s right-wing Manchester (N.H.) Union-Leader, charged presidential candidate Ed Muskie with condoning an ethnic slur against people of French Canadian descent by using the word “Canuck.” It became known as the Canuck letter, and according to Deep Throat, “It was a White House Operation—done inside the gates surrounding the White House and the Executive Office Building. Is that enough?”

No. Woodward pressed for more.

“Okay, this is very serious. You can safely say that 50 people—more than 50—worked for the White House and CRP to play games and spy and sabotage.”

Woodward left the meeting with a list that included “bugging, following people, false press leaks, fake letters, canceling campaign rallies, investigating campaign workers’ private lives, planting spies, stealing documents, planting provocateurs.”

Many people wondered then—and even now, so many years later—how the Post dared ride over the constant denials of the President of the United States, and the Attorney General of the United States, and the top presidential aides like H. R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, and Charles Colson, and stand by the guns of Woodward, Bernstein, and Deep Throat. The answer isn’t that complicated. Little by little, week by week, we knew our information was right when we heard it, right when we checked it once and right when we checked it again. Little by little we came to realize that the White House information was wrong as soon as we checked it. That all these statesmen were lying.

Woodward was in the office a few hours later writing up his notes. We had roughed out a plan for three stories:

• A Woodstein special on the espionage and sabotage campaign of fifty agents from the White House and CRP. Surely the lead of the next day’s paper.

• A Bernstein sidebar on Donald Segretti, a California lawyer recruited to play dirty tricks on selected “enemies.”

• A Woodward sidebar.

Not just another day at the office, and it wasn’t 10:00 A.M. yet, but all this was about to change.

Marilyn Berger covered foreign affairs thoroughly and skillfully for the Post, an attractive single woman, who loved being involved with the day’s big story, whatever it was, like all good journalists. Bernstein was at the water cooler getting set to write the Canuck letter story—he had already sharpened every pencil at his desk and been to the bathroom three times. Berger came up to him and asked casually if “they” knew about the Canuck letter. This was an interesting question, since Woodward had only known about the Canuck letter since six o’clock that morning, and he hadn’t told Bernstein until 9:00 A.M.

“What do you mean?” Bernstein asked with poorly disguised nonchalance.

“Ken Clawson wrote the Canuck letter,” Berger announced, out of the blue. And it turned out Clawson had told her about it over a drink at her apartment one night a couple of weeks earlier. This was major news. First, because it confirmed part of Deep Throat’s hoursold bombshell. Second, because Clawson had worked for The Washington Post, covering Attorney General Mitchell and the Justice Department, before joining Nixon’s staff only a short time earlier. During the next eight hours, he found himself deeper and deeper in the soup, as he realized that the Post was about to say that he had told a Post reporter that he had written a fraudulent letter to the New Hampshire paper, the Manchester Union-Leader, and helped force Democratic presidential candidate Ed Muskie out of the race.

Clawson knew we would print his denial, but he seemed more worried that we would say where he had admitted authorship of the fraudulent letter. He was on the telephone most of the afternoon—to Berger, to Woodward and Bernstein, and to me. Clawson asked me specifically not to say he had been in Berger’s apartment. The venue was of no importance to the story, but I wasn’t about to let Clawson off the hook until we had everything out of him that we were going to get.

Late that afternoon (after 6:00 P.M.) we decided to combine all three stories into one big ball-breaker. It often seemed that every big Watergate story came together only late in the afternoon. Howard Simons and I would bet each other that as we left for home around eight o’clock, either Woodward or Bernstein would come sidling up to us and say something like, “We think we may have a pretty good story here.”

One of the best “pretty good” stories they came up with in October was the first outline of the true scope of the Watergate conspiracy, showing a broad pattern of illicit behavior. It appeared in the Post on October 10, 1972.

FBI agents have established that the Watergate bugging incident stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of President Nixon’s re-election and directed by officials of the White House and the Committee for the Re-election of the President.

The activities, according to information in FBI and Department of Justice files, were aimed at all the major Democratic presidential candidates and—since 1971—represented a basic strategy of the re-election effort.

During the Watergate investigation federal agents established that hundreds of thousands of dollars in Nixon campaign contributions had been set aside to pay for an extensive undercover campaign aimed at discrediting individual Democratic presidential candidates and disrupting their campaigns.

“Intelligence work” is normal during a campaign and is said to be carried out by both political parties. But federal investigators said what they uncovered being done by the Nixon forces is unprecedented in scope and intensity.

The next two paragraphs described the dirty tricks:

Following members of Democratic candidates’ families; assembling dossiers of their personal lives; forging letters and distributing them under the candidates’ letterheads; leaking false and manufactured items to the press; throwing campaign schedules into disarray; seizing confidential campaign files and investigating the lives of dozens of campaign workers.

In addition, investigators said the activities included planting provocateurs in the ranks of organizations expected to demonstrate at the Republican and Democratic conventions; and investigating potential donors to the Nixon campaign before their contributions were solicited.

The story then told about the Canuck letter for ten paragraphs: how White House staffer Ken Clawson had told Marilyn Berger he had written the Canuck letter that mortally wounded Ed Muskie’s presidential candidacy, but now denied it. We didn’t get to Donald Segretti and his dirty tricks, and the involvement of at least fifty undercover Nixon operatives who traveled throughout the country trying to disrupt and spy on Democratic campaigns, until the story jumped to an inside page at paragraph 19 (of a 65-paragraph story).

The White House called the story a “collection of absurdities,” but the New York Times had its own story on the front page, largely quoting the Post. There are many, many rewards in the newspaper business, but one of the finest comes with reading the competition quoting your paper on its front page.

On October 15, Bernstein and Woodward (we alternated the order of their names in bylines) revealed that Nixon’s appointments secretary, Dwight Chapin, and an ex-White House aide named Donald H. Segretti were integral parts of a White House spying and sabotage operation.

On October 24, our Watergate machine blew a fuse. We had been pursuing the money, tracing it deeper and deeper into the White House and higher and higher up the White House ladder. We had followed it to the presidential appointments secretary, Dwight Chapin, but we had never been able to trace any money to Haldeman, Ehrlichman, or the president himself. Hugh Sloan, committee treasurer of the CRP, had confirmed to Woodward and Bernstein that five men controlled the White House secret fund, used to finance all political sabotage and payoffs. Woodward and Bernstein knew who four of them were when they met with Sloan on October 23: Jeb Magruder, Maurice Stans, John Mitchell, and Herbert Kalmbach, Nixon’s personal attorney. They suspected Bob Haldeman was the fifth, but had been unable to confirm. Sloan was less than forthcoming. Was it Ehrlichman? No. Was it Colson? No. Was it the president himself? No. Then it had to be Haldeman. It was a question, not a statement.

As Woodward and Bernstein later recalled this back and forth in their book All the President’s Men, Sloan said, “Let me put it this way. I have no problems if you write a story like that.” Then it’s correct? Woodward asked. And Sloan finally said yes.

Woodward felt Sloan’s “yes” specifically included the fact that he had named Haldeman as one of the five men who controlled the secret fund to FBI investigators and in his grand jury testimony.

One source, solid, now. Deep Throat was two, but we could never quote him, and so we needed at least one more on a story this important. And this is where we got in trouble. With Woodward listening on an extension, Bernstein got an FBI agent to confirm that the bureau “got Haldeman’s name in connection with his control over the secret fund,” and that “it also came out in the grand jury.” When Bernstein asked him if he was sure Haldeman was the fifth man in control of the secret fund, the agent replied, “Yeah, Haldeman. John Haldeman.”

That was a “tilt,” of course. Haldeman was Bob. And John could be Ehrlichman, though that had been denied. Carl called the agent back, and he said he never could remember names. It was Bob Haldeman. And the boys were ready to write.

As we got closer and closer to Nixon, I was becoming more and more cautious. This time, with Simons, Sussman, and Rosenfeld, we went after Woodward and Bernstein like prosecutors, demanding to know word for bloody word what each source had said in reply to what questions, not the general meaning but the exact words. Then I finally said, “Go.” It was October 24, for the issue of October 25, 1972.

Meanwhile, Bernstein had gone after a fourth source, even as the story was being set in the composing room, and hit upon a gimmick that plowed new—and unholy—ground in the annals of journalism, and also could have gotten us in major trouble at just the wrong time. He tried one more source, a Justice Department lawyer, who told him he would like to help, but could not. Bernstein read the lawyer the story, and then suggested he was going to count to ten. If the lawyer found nothing wrong with our story, he would still be on the telephone when Bernstein reached ten. If something was wrong with the story, the lawyer would hang up before Bernstein reached ten. Or something.

Bernstein reached ten and the lawyer was still at the other end of the line.

All I could think of was the Sherlock Holmes tale about the dog that didn’t bark. The lawyer who didn’t hang up.

I watched the shit hit the fan early next day on the CBS Morning News. To my eternal horror, there was correspondent Dan Schorr with a microphone jammed in the face of Hugh Sloan and his lawyer. And the lawyer was categorical in his denial: Sloan had not testified to the grand jury that Haldeman controlled the secret fund.

No one can imagine how I felt. We had written more than fifty Watergate stories, in the teeth of one of history’s great political cover-ups, and we hadn’t made a material mistake. Not one. We had been supported by the publisher every step of the way, and she had withstood enormous pressures to stand by our side. Pressures from her friends as well as her enemies. And now this.

The denials exploded all around us all day like incoming artillery shells. After Sloan came Ron Ziegler, Clark MacGregor, and good old Bob Dole, always ready to pile on. Some of the denials sounded technical, almost hair-splitting to us. But if it looked like a denial, smelled like a denial, and read like a denial, it was a denial, as far as the readers were concerned. Newspapers which hadn’t bothered to run the story about Haldeman’s control of the secret fund headlined the various White House denials; major newspapers like the Chicago Tribune, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Denver Post, the Minneapolis Tribune.

Bernstein and Woodward, tails between their legs and my unhappiness ringing in their ears, started out on the long road of finding out what had gone wrong. I was sore . . . at them and at myself. It was a jackass scheme, and I should have caught it. All along, we had wanted to “win” without knowing what winning might turn out to be. But all along, we knew we could not afford any mistakes. And now we had made one. The next step was to find out where we had gone wrong, and how to get back in our stride.

Election Day was less than a month off, and the Nixon White House had settled on its ultimate defense. The night before our “mistake” ran on page one, Bob Dole, the GOP chairman, had given a speech in Baltimore with an astounding fifty-seven critical references to the Post:

The greatest political scandal of this campaign is the brazen manner in which, without benefit of clergy, The Washington Post has set up housekeeping with the McGovern campaign. With his campaign collapsing around his ears, Mr. McGovern some weeks back became the beneficiary of the most extensive journalistic rescue-and-salvage operation in American politics.

The Post’s reputation for objectivity and credibility have sunk so low they have almost disappeared from the Big Board altogether.

There is a cultural and social affinity between the McGovernites and the Post executives and editors. They belong to the same elite; they can be found living cheek by jowl in the same exclusive neighborhood, and hob-nobbing at the same Georgetown parties. . . .

It is only The Washington Post which deliberately mixes together illegal and unethical episodes, like the Watergate caper, with shenanigans which have been the stock in trade of political pranksters from the day I came into politics.

Now, Mr. Bradlee, an old Kennedy coat-holder, is entitled to his views. But when he allows his paper to be used as a political instrument of the McGovernite campaign; when he himself travels the country as a small-bore McGovern surrogate, then he and his publication should expect appropriate treatment, which they will with regularity receive.

The Republican Party has been the victim of a barrage of unfounded and unsubstantiated allegations by George McGovern and his partner in mud-slinging, The Washington Post.

Ziegler said the Post’s stories “are based on hearsay, innuendo, guilt by association. . . . Since the Watergate case broke, people have been trying to link the case with the White House . . . and no link has been established . . . because no link exists.” And Clark MacGregor, who had succeeded Mitchell as director of Nixon’s campaign, weighed in with a no-questions-allowed press conference, where he allowed as how “The Washington Post’s credibility has today sunk lower than that of George McGovern. Using innuendo, third person hearsay, unsubstantiated charges, anonymous sources and huge scare headlines, the Post has maliciously sought to give the appearance of a direct connection between the White House and the Watergate—a charge the Post knows and half a dozen investigations have found to be false. The hallmark of the Post’s campaign is hypocrisy.”

Mercifully for us, on the afternoon of October 26, Henry Kissinger gave a press conference at the White House to announce that “peace was at hand in Vietnam,” and that gave us a little breathing room, since it occupied both the press and the Nixon administration. And after a long conversation with Sloan’s lawyer, James Stoner, and a few more days of digging, the truth emerged (as Walter Lippmann so long ago promised it would): Haldeman did have control of the secret fund, despite all the technical denials, but Sloan had not testified to that effect in front of the grand jury. He hadn’t told the grand jury about Haldeman’s control, because the jury hadn’t asked him about Haldeman’s involvement.

Sloan finally told us, “Our denial was strictly limited.” And so be it; they caused us anguish we had never felt before.

We had already tied Segretti to Dwight Chapin, Nixon’s appointments secretary, and to Herbert Kalmbach, Nixon’s lawyer, so we were keeping the pressure on. But it was lonely out there, targeted as we were more and more by Messrs. Dole, MacGregor, Ziegler and company. With only a few exceptions (Time magazine, the L.A. Times, the New York Times, and each of them only rarely during this period), the press was concentrating on the political race between Nixon and McGovern, seemingly content to leave us alone and “see what you guys can come up with,” as one editor told me. It was discouraging as hell.

In the middle of October, my old Newsweek buddy Gordon Manning, vice president and director at CBS, had called with good news.

“You’ve never been able to do anything without me, Bradlee,” he started, “and now I’m going to save your ass in this Watergate thing. Cronkite and I have gotten CBS to agree to do two back-to-back long pieces on the ‘Evening News’ about Watergate. We’re going to make you famous.”

That was good news, because television had been generally unable to cope with Watergate, and national acceptance of the story had lagged accordingly. Probably because it would never be a visual story until the Senate hearings five long months later, except for a few shots of Dan Rather and Nixon shouting at each other in press conferences.

“There’s only one thing,” Manning went on. “You’ve got to let us have the documents. We don’t have any.”

“Gordon, there aren’t any documents,” I told him. “Believe it or not. Of course, we’ll help you, but we have information. We don’t have photocopies, Xeroxes, nothing.”

“Come on, Benny,” he insisted. “We’ll make you famous, and you guys need us. You’re all alone out there.”

True enough, as I saw it, but he wouldn’t believe me. Instead, he sent down some hot-shot producer, and we told him what we knew and a good part of what we suspected. But he finally became convinced that Walter was not going to get nonexistent documents.

When the pieces finally ran (fourteen minutes on October 27, and eight minutes the next night), they had a powerful impact everywhere—on the Post, on the politicians (if not the voters), and on newsrooms outside Washington. Somehow the Great White Father, Walter Cronkite, the most trusted man in America, had blessed the story by spending so much time on it. The lack of documents had forced Gordon “Think Visual” Manning and company to use giant blow-ups of Washington Post logos, and front-page stories. We were thrilled. No new ground was broken, but the broadcasts validated the Post’s stories in the public’s mind and gave us all an immense morale boost.

On November 7, 1972, the voters reelected Richard Nixon by one of the greatest margins in American history. He won more than 60 percent of the vote, and every state in the union except Massachusetts, an historic sweep. And one of the first orders of business in the second term was retaliation against the Post . . . most of it petty, but all of it vaguely threatening.

After the election, Chuck Colson—spang in the middle of all the obstruction of justice that eventually landed him in jail—gave a speech to the New England newspaper editors that stands by itself as a monument to lying and general dishonesty:

Ben Bradlee now sees himself as the self-appointed leader of what Boston’s Teddy White once described as “that tiny little fringe of arrogant elitists who infect the healthy mainstream of American journalism with their own peculiar view of the world.”

I think if Bradlee ever left the Georgetown cocktail circuit, where he and his pals dine on third-hand information and gossip and rumor, he might discover out here the real America, and he might learn that all truth and all knowledge and all superior wisdom doesn’t emanate exclusively from that small little clique in Georgetown, and that the rest of the country isn’t just sitting out here waiting to be told what they’re supposed to think. . . .

An independent investigation was conducted in the White House which corroborated the findings of the FBI that no one in the White House was in any way involved in the Watergate affair.

A reporter for the Washington Star-News was promised by Chuck Colson that the administration would bury the Post. “Come in with your breadbasket, and we’ll fill it,” Colson is quoted as telling other reporters by city editor Barry Sussman, by then in charge of our day-to-day Watergate reporting. And sure enough, Nixon’s first exclusive interview in his second term went to Garnett Horner, of the Star-News. He didn’t say a damn thing in the interview, but we could identify a shot across our bow when we saw one. Some government officials stopped notifying Post reporters of bread-and-butter developments on their beats. One of the most distinguished—and unanimously loved—reporters on The Washington Post was Dorothy McCardle, age sixty-eight, a white-haired grandmother who had covered the Lindbergh kidnapping for the Philadelphia Inquirer. She covered the East Wing of the White House, the source of all information about White House social gatherings of all kinds, and she was systematically excluded from all pools, where she would have a chance to report directly, rather than accept force-fed handouts. Her exclusion actually boomeranged against the White House, after the Star-News wrote an editorial saying they would boycott social events rather than be used as an instrument of revenge against McCardle.

Behind the scenes, and unknown to Post officials until months later, Nixon himself, plus Haldeman and others, were plotting hardball revenge against the paper. The Post was going to have “damnable, damnable problems,” according to the transcripts of the president’s post-election conversations with his inner circle, when it came time for its television station licenses to be renewed.

And sure enough, we did. In those days the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) required TV license renewals every three years. By January 1973, only four challenges had been filed against all the TV stations in the United States. Three of the challenges were against Post-owned WJXT in Jacksonville, Florida, and the other was against Post-owned WPLG (for Philip L. Graham) in Miami. At least two of the challenges involved people active in Nixon’s reelection effort. And the general counsel of the Committee to Re-elect the President, J. Glenn Sedam, actually traveled to Jacksonville to talk to business leaders there about how to file challenges. *

Right after our “mistake” on October 25, Woodward, Bernstein, and the rest of us had disappeared into a black hole, where we couldn’t get anyone to talk, we couldn’t get a smell of a story. I suggested to Rosenfeld and Sussman that they keep Woodward’s and Bernstein’s heads under water until they came up with something. But without success. At the same time, the Republicans—and some of our journalist colleagues—were telling everyone: “See? As soon as the election is over, the Post can’t find anything to write about. We told you it was all politics.”

Much has been made of an incident at the end of November 1972 when Woodward and Bernstein, with my knowledge and support, tried to contact grand jurors convened to investigate Watergate. I am sure we all were influenced by Nixon’s overwhelming reelection win, on top of our own inability to break new ground in the Watergate story.

We had been told by our lawyers that talking to grand jurors was not illegal “per se,” whatever that meant in this context, although it was possibly illegal for grand jurors to talk to reporters. And we had confirmed evidence that the Nixon administration Justice Department was not presenting certain evidence to the grand jury. We felt the playing field wasn’t even to start with, given the scope of the Nixon cover-up, and the tools any administration has to cover up the truth. If key evidence was being withheld from the grand jury, we felt we had no chance to get to the truth we knew was there.

Our grand jury episode began when Post news editor Ben Cason was emptying the trash at his house in northern Virginia at the same time his neighbor was emptying his trash. The neighbor told Cason his aunt was on a grand jury, which he thought was the Watergate grand jury. His aunt was a Republican who disliked Richard Nixon—just to put a little frosting on the cake.

We went into conferences with our lawyers and ourselves. Ed Williams agreed—reluctantly—that Woodward and Bernstein could talk to the lady juror, but urged extreme caution, suggesting they merely ask the lady if she wanted to talk. I insisted that the reporters identify themselves as Washington Post reporters, and urged Bernstein to try to be subtle. After they left to call on the woman, we all stayed glued to the phone . . . but she wasn’t home. Next morning, they rang her doorbell, identified themselves, and were invited in. They didn’t mention the grand jury. They just asked her casually some questions about Watergate. Woodward quotes the lady as answering: “It’s a mess, but how would I know anything about it except what I read in the papers.”

She was a grand juror, all right, but on a different grand jury, not the Watergate grand jury.

Next morning, Woodward persuaded a clerk in the U.S. District Court to let him see the master list of trial jurors and grand jurors, after promising he wouldn’t copy anything. He plowed through the file drawers, found the list of jurors on two grand juries sworn in earlier that summer, and picked the right grand jury by remembering that the foreman had an Eastern European name. In front of him lay twenty-three small orange cards, each listing the name, age, occupation, address, and telephone number of a Watergate grand juror. Fifteen feet away from him sat the clerk, suspicious eyes fixed on him.

Bob Woodward simply memorized the whole list. The first four names in about ten minutes, followed by a short visit to the men’s room, where he copied the names down in his notebook. On his next try, he memorized five cards, and asked the clerk for directions to the chief judge’s chambers. In a different men’s room, he wrote down five names, addresses, ages, and phone numbers. Back for a third try—with fourteen names to go, and the clerk becoming unmanageably suspicious—Woodward memorized the contents of six cards, wrote them down during a phony lunch break, and returned to get the last eight . . . in just forty-five minutes.

The fruits of those considerable labors were nonexistent. After trying to guess which of the twenty-three might talk, Woodward and Bernstein reached “about half a dozen,” they reported. One told them he had taken two oaths of secrecy in his life, one for the Elks and one for the grand jury, and wasn’t about to violate either one. But several grand jurors told Judge John J. Sirica early Monday morning that they had been contacted by the Post, and the shit hit the fan. “Maximum John” Sirica, so called for his tough sentences, was “some kind of pissed at you fellas,” Ed Williams told us after the judge had contacted him. But Sirica settled for a stern lecture from the bench, after the prosecutors recommended taking no action since no information had been given the reporters by the grand jurors. Sirica didn’t even identify Woodward and Bernstein in his lecture from the bench, although he had insisted that they be brought to court and seated in the front row.

In All the President’s Men, Woodward and Bernstein recall this episode in all our lives as “a seedy venture” and “a clumsy charade.” Woodward described himself as wondering “whether there was ever justification for a reporter to entice someone across the line of legality while standing safely on the right side himself.” Bernstein was described as a man “who vaguely approved of selective civil disobedience,” not “concerned about breaking the law in the abstract.” With him, the co-authors said, “it was a question of which law, and he believed that grand-jury proceedings should be inviolate.”

I don’t look at it that way. I remember figuring, after being told that it was not illegal and after insisting that we tell no lies and identify ourselves, that it was worth a shot. In the same circumstances, I’d do it again. The stakes were too high.

But the new year brought us the trial of the five Watergate burglars, plus Hunt, and the oddball zealot, Gordon Liddy: Liddy, an ex-FBI agent who had worked on the staff of John Ehrlichman, and was the administration’s unofficial expert on dirty tricks. Hunt and the four Miami burglars pleaded guilty before the trial, and the jury found Liddy and McCord guilty. We were back in business, and because the trial was a national story, the Post was not alone. In fact, before the trial ended, Sy Hersh, who had broken the story of the My Lai massacre * and was now working for the New York Times, dropped a beauty on us and the world with a detailed account of how the defendants had been paid hush money with funds ostensibly raised to reelect President Nixon. I hate to get beaten on any story, but I loved that one by my pal Hersh, because it meant the Post was no longer alone in alleging obstruction of justice by the administration—as long as we didn’t get beaten again.

Sentencing was set for late March, and when the day finally came, two men made sure that Watergate would never die, and that Richard Nixon himself was going to pay a fearful price for his role in it. The first was Judge John Sirica, and the second was James W. McCord, Jr. The date was Friday, March 23, 1973. The courtroom was crowded, and Sirica had whispered to a reporter that he would have a surprise for everyone. Sirica was always described as a former boxer. He was sixty-nine years old, small, scrappy, with a face you know but find hard to remember how. As chief judge of the U.S. District Court, he had assigned himself the Watergate burglary because he liked the limelight as much as the next judge, maybe a little more. He ran that trial with an iron hand, but he was frustrated by all the guilty pleas, and as sentencing approached he knew that he had been unable to get to the truth.

But now he suddenly had his chance. His “surprise” turned out to be a confidential letter received three days earlier from McCord in jail. Worried about being second-guessed, Sirica made his bombshell public as soon as the crowded court room came to order.

“Certain questions have been posed to me from your honor through the probation officer,” McCord’s letter began,

dealing with details of the case, motivations, intent and mitigating circumstances. In endeavoring to respond to these questions, I am whipsawed in a variety of legalities. . . .

There are further considerations which are not to be taken lightly. Several members of my family have expressed fear for my life if I disclose knowledge of the facts in this matter, either publicly or to any government representative. . . . Whereas I do not share their concerns to the same degree, nevertheless, I do believe that retaliatory measures will be taken against me, my family and my friends should I disclose such facts. Such retaliation could destroy careers, income and reputations of persons who are innocent of any guilt whatever.

But if he failed to answer Judge Sirica’s questions, McCord’s letter continued, he could

expect a much more severe sentence. . . . In the interests of justice and in the interests of restoring faith in the criminal justice system, which faith has been severely damaged in this case, I will state the following to you at this time which I hope may be of help to you in meting out justice in this case.

1. There was political pressure applied to the defendants to plead guilty and remain silent.

2. Perjury occurred during the trial in matters highly material to the very structure, orientation and impact of the government’s case, and to the motivation and intent of the defendants.

3. Others involved in the Watergate operation were not identified during the trial, when they could have been by those testifying. . . .

Following sentencing, I would appreciate the opportunity to talk with you privately in chambers. Since I cannot feel confident in talking with an FBI agent, in testifying before a grand jury whose U.S. attorneys work for the Department of Justice, or in talking with other government representatives, such a discussion would be of assistance to me.

The Watergate dam was about to burst. These were devastating charges, by the one person involved in the break-in with some stature in his community. He was a career CIA technician, not a spy with extensive dirty trick experience like Hunt, not a kook like Liddy, not a political fanatic like the men from Miami. And here he was under oath in front of a federal judge, talking about perjury, about hush money, about cover-ups by people involved intimately with the president’s closest advisers. This wasn’t some press figment of the imagination, quoting anonymous sources, whose motives could be attacked. This was an insider talking, and everyone knew it.

Sirica had to recess his court for a minute because he had a serious bellyache, but when he started to feel better, he got on with the business of sentencing the defendants for what he called “sordid, despicable and thoroughly reprehensible” crimes.

First, G. Gordon Liddy, who said nothing—cool, grinning, unafraid, respected by the criminals he had met in jail, cordially disliked by the prosecutor. On six counts of burglary and wiretapping, Liddy was sentenced to a minimum of six years and eight months and a maximum of twenty years in prison, plus a fine of $40,000. He would serve fifty-two months of actual time.

Then Howard Hunt, who pleaded emotionally for mercy: “I have lost virtually everything I cherished in life—my wife [who had died with a bag of cash in a plane crash on December 8, 1972], my job, my reputation . . . except my [four] children, who are all that remain of a once happy family. . . . I have suffered agonies I never believed a man could endure and still survive. My fate . . . is in your hands.” Judge Sirica was unmoved. He sentenced Hunt to thirty-five years in jail, and fined him $40,000. Unknown to anyone publicly, Hunt had just been paid off by the White House to remain silent. Hunt ultimately served thirty-one and a half months in jail.

The Miami men, also silent, got forty years and $50,000 fines. The sentences for Hunt and the burglars were especially heavy, but they were also provisional. Sirica told them he would rethink their sentences if they decided to spill the beans and tell what they knew. “I hold out no promises or hopes of any kind to you in this matter,” he told them, “but I do say that should you decide to speak freely, I would have to weigh that factor in appraising what sentence will finally be imposed in each case.” None of the Miami men served more than fourteen months.

For the first time, really, I felt in my guts that we were going to win. And winning would mean all the truth. Every bit. I had no idea still how it would all come out, but I no longer believed Watergate would end in a tie. My great fear had always been that it would just peter out, with The Washington Post and the rest of the good guys saying it was an awful conspiracy, and the White House saying it was just the press and politics. Now, I knew there was going to be a winner. And I knew it was not going to be the president or the White House gang.

For the record, I told Woodward and Bernstein to go find out who were the people McCord said had perjured themselves, and who had put what pressure on whom. Privately, I was so damned excited I couldn’t sit down. I called Kay Graham in Singapore with the news, and I had lunch with Buchwald and Williams.

That always made me feel good.

Williams and Buchwald and I had been eating lunch together so long and so often that before we knew it we had our own de facto club. First at the Sans Souci restaurant, where Buchwald had conned the owner into putting his name on a plaque over his favorite banquette seat, later at the Maison Blanche, and sometimes at Duke Zeibert’s. This was an extremely exclusive and sexist club. Its only by-law (unwritten) was that no one else could join. In fact, its only purpose was to keep good friends out—Jack Valenti, George Stevens, Phil Geyelin, Joe Califano and company. Aspirants could buy us lunch and they could eat with us, but they wouldn’t make it past the membership committee.

In all the years of its existence, the only exception was Katharine Graham. Once Buchwald sent her the following memo after inviting her to lunch:

This is a list of the guests at the luncheon tomorrow which will help you know who they are and what to talk about.

1. Benjamin Bradlee is the managing editor of The Washington Post, which is a very influential newspaper in the Nation’s Capital. Bradlee’s interests are football and girls—not necessarily in that order—but if you wish, you can talk to him about the newspaper business.

2. Edward Bennett Williams is a leading criminal lawyer in Washington who has defended such diversified clients as Milwaukee Phil, Arizona Pete, and Three-Finger George. He is a very strong Catholic, so I suggest you discuss religion with him—particularly birth control and if priests should get married.

3. Art Buchwald is the columnist for The Washington Posty. He is terribly charming and can talk on any subject. I think that of the three, you will find him the most interesting.

I doubt if there will be any toast, except to the President of the United States.

Kay would eat with us from time to time, and Williams and Buchwald would always tell her that they had proposed her for membership but I had blackballed her. Finally, on her sixty-fifth birthday, we took her to lunch and told her she had been elected, and we toasted her induction with champagne. But at the end of the meal, Williams broke the news to our new member—his prestigious client and my boss: Unfortunately, the club had an age limit, and all members had to resign when they reached sixty-five.

More normally, the three of us would eat together, and two of us would pair off on the third guy. Buchwald and I would dump on some of Ed’s more unsavory clients, especially Victor Posner, the shady Miami businessman with a well-known taste for teenage girls. Ed and I would go after Art’s pronouncements about what was really going on in Washington. And the two of them would gang up on me, generally complaining that anything they told me ended up somewhere in the paper. This was true, especially from Williams, but I figured he knew how I made my living, and never told me anything he didn’t want me to know. He never once told me about his lawsuits, and he had the most interesting clients in town. From time to time during our meals—liberated as we all were—we would play quick games of “Wouldya” as persons of the female persuasion crossed our fields of vision.

Male friends are important to me, and the ones that I love are vitally important. These two guys, I loved. Differently. Friendship with Buchwald requires constant attention. If I didn’t call Art on the phone pretty regularly, I would start hearing from mutual friends like Harry Dalinsky, who ran all our lives from behind the counter at the Georgetown Pharmacy, that Art’s feelings were hurt. Art shared with me his complicated courtship with the wonderful Ann McGarry. There was some mixture of sensibility and vulnerability plus the twinkle and the humor that made Art unique. And irresistible. Then, and now.

With Williams, our friendship could survive weeks of negligence, and flourish minutes after renewed contact. From the day of our first lunch at some greasy spoon luncheonette near the courthouse, two things were quickly obvious to me about Williams: wherever Ed was, there was a good story, and whatever he did, he had a good time and it showed. He was smart, tough, funny, and soft-hearted, and he didn’t take himself too seriously, while taking his jobs extremely seriously. I knew right away I wanted him by my side if I ever got in trouble. I missed him the moment he died almost forty years later, and I have missed him and his warmth and humor and common sense every day since.

After Judge Sirica’s sentencing of the Watergate burglars, the Washington press corps began full-time pursuit of the story, falling all over each other like a pack of beagles, in Stewart Alsop’s apt phrase, noisily barking, sometimes at the fresh scent of a new lead, but often at the scent and sight of each other.

The air was thick with lies, and the president was the lead liar. In April 1973, Nixon said he “began intensive new inquiries.” That was a lie. In the same statement, he said he condemned “any attempts to cover up in this case, no matter who is involved.” That was another lie. He, himself, was leading the cover-up of Watergate. Ziegler was lying so often, he had to coin the expression “inoperative statements” when he needed to find the euphemistic way to admit that he had lied. Today’s statement was called the “operative statement,” while earlier statements were dismissed as “inoperative.” Not even George Orwell would have dared to try that in 1984. * Kleindienst even had to lie to get confirmed, when he told the Senate that President Nixon had not interfered in a 1972 Justice Department investigation of International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT). *

Henry Kissinger contributed uniquely to efforts to play down Watergate by saying that the nation had to decide whether it could stand “an orgy of recrimination,” suggesting the nation might be better off by forgetting Watergate. Spiro Agnew, a man who had accepted payoffs in the Executive Office Building as a sitting vice president, found the gall somewhere to tell a bunch of students he would resign if Watergate made him unable to continue in “good conscience.” The acting director of the FBI, L. Patrick Gray, destroyed two folders of Watergate evidence, given him by Ehrlichman and Dean, on July 3, 1972, and was asked to withdraw his nomination nine months later. Re orters who wrote stories Kissinger didn’t want disclosed got their phones tapped. It was revealed that Liddy and Hunt had burglarized the files of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in 1971, looking for information to smear Ellsberg and get even with him for making the Pentagon Papers available. And finally Kleindienst resigned, replaced by Elliot Richardson, the incorruptible Brahmin from Boston.

The focus of the Watergate affair had shifted from Sirica’s courtroom and the Post’s Woodward and Bernstein pieces to Senator Ervin’s committee, and the investigations being conducted by the committee staff, under committee counsel Sam Dash. Reporters were having a field day, simply because of the sudden multiplication of news sources. As the principals were first interviewed by committee investigators, then behind closed doors before members of the committee, the opportunities presented to each senator and each investigator for some serious leaking were proving irresistible.

Senators, on and off the Ervin Committee, were looking for high ground. Spiro Agnew announced that he was “appalled” by Watergate. Richard Kleindienst, the new Attorney General, about to be forced to resign himself, was the first to mention publicly the dreaded “I” word (Impeachment).

Nixon explained himself so many times, it was hard not to be confused. My own favorite rationale came on April 30 when the president tried one more time to con the American people in a latter-day Checkers speech: “The easiest course would be for me to blame those to whom I had delegated the responsibility to run the campaign, but that would be the cowardly thing to do.” This from the man who ten days earlier, it turns out, had told his assistant attorney general in charge of the criminal division to “stay out of” the break-in to Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office because “that is a national security matter.” An awesome lie.

It seemed as if reporters were just bringing their buckets to work, sure that they would be filled with the latest sleazy revelations without any great work on their part. No reporter had ever seen anything like this before.

And most remarkable of all, no one yet knew the complete story. The existence of the White House tapes, with their vivid and detailed self-incrimination, was still unknown to us—or to any investigator. At the Post, where reporters and editors knew more than almost anyone else, we were still trying to fit each new piece of information into the puzzle. We grew increasingly confident that this was the greatest political scandal of our time, and we still didn’t know the half of it.

In the middle of all this, I got a call from my old friend Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, the founding editor of the French weekly, L’Express, with a startling invitation. He wanted to put me on the cover of L’Express’s twentieth anniversary issue, to symbolize the importance to society of a free and independent press. They were in something of a hurry. (I wondered—only briefly—whether the regularly scheduled cover had just fallen through and they were in a real jam.) A photographer was on his way to take the cover photo, because JJ-SS was sure I would agree. They would fly Tony and me to Paris twenty-four hours later for the magazine’s big birthday party, where “le tout Paris” would be gathered. I would have to give only a five-minute speech in French, but then we would be free to enjoy an April-in-Paris weekend by ourselves.

Meg Greenfield—her warmth and humor sometimes overpowered the brainy, intellectual image reflected in her Newsweek column picture.

Howard Simons—the great eclectic mind of the newsroom. He invented SMERSH (Science, Medicine, Education, Religion, and all that SHit).

The pressmen’s strike for five months in 1974 and 1975 killed the union and gave the Post vitally needed control of its production. That’s the union president, Charlie Davis, carrying the particularly tasteless sign. He moved on to bartending.

The third generation takes over in 1979 when Don Graham becomes publisher. Katharine had succeeded her husband in August 1963 and created the modem Washington Post.

In the 1980s I started moving away from my image as a bookie or a jewel thief, and started being pensive when photographed.

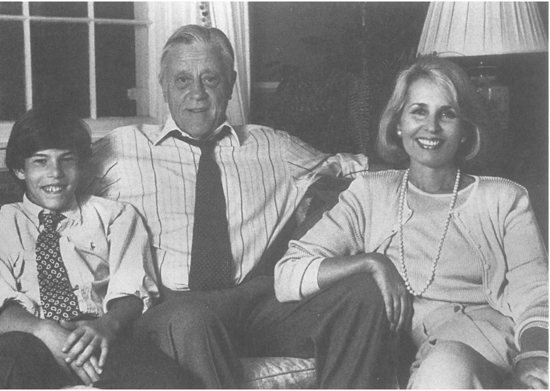

This is a meeting of our club, just after turning down Katharine Graham for membership. Edward Bennett Williams with his arms around Art Buchwald and me.

Artie and I at one of the political conventions, teasing our photographer friend Diana Walker.

Sally Quinn clowning, early in her life as a Style reporter, still an impossible dream in my eyes.

I asked artist Steve Mendelson to draw this—to give to reporters clinically unable to admit they sometimes missed a story, even part of a story.

Ward Just typified the new breed of smart, hungry reporters who could write like angels. We stripped his story about the patrol where he got his ass full of shrapnel over the masthead with the headline “Ain’t Nobody Here but Charlie Cong.”

The new pope was a Pole, and four days later, October 20, 1978, Sally and I were married.

Sister Connie and brother Freddy in Leesburg, Virginia, for Marina’s wedding, October 27, 1984.

There’s no word for former stepchildren, but here they are at Marina’s wedding, sandwiched between Dino and Ben, Jr.: Rosamond Casey and Andy, Tammy, and Nancy Pittman.

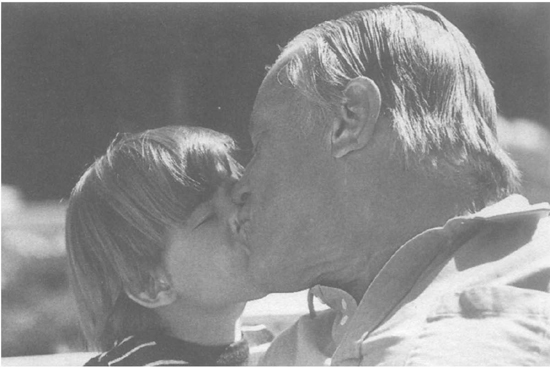

Quinn and his dad. It doesn’t get any better than that.

Ben, Jr., Dino, and Quinn hamming it up at Ben’s wedding in Cambridge, November 17, 1990.

Harry “Doc” Dalinsky outside his Georgetown drugstore, where he dispensed wisdom, love, and bagels to his friends for almost forty years.

Flirting in Central Park in 1975.

Parenting in Georgetown, 1995. Quinn Bradlee, newly a teenager.

This is Porto Bello as we found it in 1990, on the St. Mary’s River in southern Maryland.

This is Porto Bello in the June 1995 issue of Architectural Digest, a glorious expression of Sally Quinn’s taste and Washington Post stock.

Moving out, moving on . . . with a hug from Len Downie, the new executive editor, and a fantastic send-off from the troops.

The Graham publishers and one of their chief beneficiaries.

Without pause, I said I would do it, with great delight. And I called Tony to tell her to start packing for a roller-coaster ride, only to be told that she did not want to go. I was stunned to realize that the prospect of a unique adventure together was no longer attractive.

But I went anyway, somewhere between glad, mad, and sad.

Servan-Schreiber was an interesting man in the early seventies, not yet overwhelmed by his ego. He and his longtime friend and colleague, the spectacular Françoise Giroud, disciples of Pierre Mendès-France, had started L’Express in 1953, and they quickly made it the exciting weekly journal of intelligence and relevance.

Two hours after I landed in Paris, I walked into a mirrored ballroom in a downtown hotel where at least fifty four- by six-feet posters of me on the cover of L’Express stared out at the glitzy crowd. I was scared to death—by the pictures of me, and by the prospect of making a speech in French. I thought I had arranged for Nicole Salinger, the wife of Pierre, to help me translate my thoughts into decent French, but she missed connections and I had to write it myself.

The rest of the night dissolved into a fog of flattery. At the end of it, I found myself with an attractive escort. I didn’t want to sleep alone on this night of “triumph,” and wondered if she would be interested in sleeping with me. She would, she said, and she did. And the next day, I flew back to Washington, feeling not quite as guilty as I had expected.

Life on the ladder of fame was something that all of us were still struggling with, and did not yet understand. I knew I was on it, but I didn’t know how many rungs I was going to get to climb. It is one thing to have a page-one byline, but that notoriety is pretty much confined to your mother and a few friends. It is another thing to be the subject of a page-one story, as I had been when the French expelled me for contacting the Algerian rebels. But that was a three-day flash in the pan, preoccupying to me, but of limited interest to the rest of the world. Now I had been on the cover of a news magazine. Profiles were showing up in more or less serious parts of the press. Reporters were calling me for quotes. I remembered once more Russ Wiggins’s importunities that journalists be longed in the audience, not on the stage, but I was plainly not following them. In fact, I felt rattled by them. All of us seek evidence of our effectiveness, and when that evidence turns public, it is hard to pretend that it doesn’t feel good.

I came back from Paris to Washington to a cascade of page-one stories that would have been unbelievable only a few weeks before.

April 1973 was probably the worst month ever for the Nixon White House. The Ervin Committee, which had been created in February to investigate the Watergate break-in and related allegations, was up and running. Its members were leaking to the press like sieves as they jockeyed for headlines, even though televised hearings were still a month off. Liddy was held in contempt of court for refusing to testify to the grand jury. A Wall Street Journal poll showed that a majority of Americans now believed that the president knew about the cover-up. On April 12, the Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate reporting. Newspaper reports that month by the Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times showed:

• A Mitchell aide (Frederick C. LaRue) had received $70,000, to pay hush money for Watergate conspirators.

• Mitchell had been shown logs of the Watergate wiretaps.

• Magruder told the grand jury that Dean and Mitchell had approved the Watergate bugging.

• Acting FBI director Patrick Gray was revealed to have destroyed two folders taken from Howard Hunt’s safe in the White House, immediately after the Watergate break-in, and was forced to resign in humiliation.

• The Ellsberg trial ended in a mistrial, after the judge reported prosecutors had withheld evidence.

• The Ellsberg judge revealed that Liddy and Hunt had burglarized Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office, while they were working out of the White House.

• And on the last day of the month, Big Casino: Ehrlichman and Haldeman were tossed over the side, and still the ship sank on, as the new Attorney General, Kleindienst, “resigned,” John Dean was fired, Len Garment was named White House counsel, and Elliot Richardson became Attorney General. The press could barely keep up with the news, and the Ervin Committee hearings hadn’t even started.

In the summer 1973 issue of the Columbia Journalism Review, James McCartney, a national correspondent for Knight Newspapers, described that last day in April thusly:

It was 11:55 a.m., on April 30, and Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee, 51, executive editor of The Washington Post, chatted with a visitor, feet on the desk, idly attempting to toss a plastic toy basketball through a hoop mounted on an office window 12’ away. The inevitable subject of conversation: Watergate. Howard Simons, the Post’s managing editor, slipped into the room to interrupt: “Nixon has accepted the resignations of Ehrlichman and Haldeman and Dean. Kleindienst is out and Richardson is the new AG.”

For a split second, Ben Bradlee’s mouth dropped open with an expression of sheer delight. Then he put one cheek on the desk, eyes closed, and banged the desk repeatedly with his fist. In a moment, he recovered. “How do you like them apples?” he said to the grinning Simons. “Not a bad start.”

Bradlee couldn’t restrain himself . . . and shouted across two rows of desks to . . . Woodward . . . “Not bad, Bob. Not half bad!”

The day after the resignations, one of the least expected wire service stories in my lifetime was dropped on my desk by a copy boy . . . from United Press International:

White House Press Secretary Ronald Ziegler publicly apologized today to the Washington Post and two of its reporters for his earlier criticism of their investigating reporting of the Watergate conspiracy.

At the White House briefing, a reporter asked Ziegler if the White House didn’t owe the Post an apology.

“In thinking of it all at this point in time, yes,” Ziegler said, “I would apologize to the Post, and I would apologize to Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein. . . . We would all have to say that mistakes were made in terms of comments. I was over-enthusiastic in my comments about the Post, particularly if you look at them in the context of developments that have taken place. . . . When we are wrong, we are wrong, as we were in that case.”

As Ziegler finished he started to say “But. . . .” He was cut off by a reporter who said: “Now, don’t take it back, Ron.”

Ron Ziegler was a small-bore man, over his head, and riding a bad horse. I feel sorrier for him today than I did then, and I’ll never forget his apology, but a man can fairly be judged by the quality of his heroes, by the quality of the leaders he chooses to follow.

Just after two in the morning on May 16, 1973, I got a call from Bernstein. He was calling from a public telephone nearby, to say that he and Woodward had to see me right away. In a scene right out of a le Carré spy novel, they sat down silently in my living room and handed me a memo, written by Woodward a few hours earlier after a dramatic encounter with Deep Throat. Specifically, Deep Throat had said, “Everyone’s life is in danger.”

That concentrated my mind for real, and I started reading the memo:

Dean talked with Senator [Howard] Baker after Watergate Committee formed and Baker is in the bag completely, reporting back directly to White House. . . .

President threatened Dean personally and said if he ever revealed the national security activities that president would insure he went to jail.

Mitchell started doing covert national and international things early, and then involved everyone else. The list is longer than anyone could imagine.

Caulfield [one time NYC cop John J. Caulfield, who had done under-cover and investigative work for the White House. met McCord and said that the president knows that we are meeting and he offers you executive clemency and you’ll only have to spend about 11 months in jail.

Caulfield threatened McCord and said, “Your life is no good in this country if you don’t cooperate.”

The covert activities involve the whole U.S. intelligence community and are incredible. Deep Throat refused to give specifics because it is against the law.

The cover-up had little to do with Watergate, but was mainly to protect the covert operations.

The president himself has been blackmailed. When Hunt became involved, he decided that the conspirators should get some money for this. Hunt started an “extortion” racket of the rankest kind.

Cover-up cost to be about $1 million. Everyone is involved—Haldeman, Ehrlichman, the president, Dean, Mardian, Caulfield and Mitchell. They all had a problem getting the money and couldn’t trust anyone, so they started raising money on the outside and chipping in their own personal funds. Mitchell couldn’t meet his quota and . . . they cut Mitchell loose.

C.I.A. people can testify that Haldeman and Ehrlichman said that the president orders you to carry this out, meaning the Watergate cover-up . . . Walters and Helms and maybe others.

Apparently, though this is not clear, these guys in the White House were out to make money and a few of them went wild trying.

Dean acted as a go-between between Haldeman-Ehrlichman and Mitchell-LaRue.

The documents that Dean has are much more than anyone has imagined and they are quite detailed.

Liddy told Dean that they could shoot him and/or that he would shoot himself, but that he would never talk and always be a good soldier.

Hunt was key to much of the crazy stuff and he used the Watergate arrests to get money . . . first $100,000 and then kept going back for more. . . .

Unreal atmosphere around the White House—realizing it is curtains on one hand and on the other trying to laugh it off and go on with business. President has had fits of “dangerous” depression.