WHILE LUCY Stone was growing up on a Massachusetts farm, Elizabeth Cady was living a far different girlhood in upstate New York. Elizabeth’s father, Daniel Cady, a successful lawyer and judge, provided a comfortable middle-class home for his wife and children in Johnstown, New York.

Elizabeth grew up in a warm house with plenty of food to eat and clothes to wear, and she went to school with all the other boys and girls in town. Hired men and women helped with the work at home, and a black slave named Peter kept an eye on Elizabeth and the other Cadys. With her mop of curly blond hair and skirts short enough to move freely, Elizabeth ran the streets of Johnstown with her siblings and friends.

Elizabeth’s mother, Margaret, married when she was 17. Over the next 25 years of her life, she gave birth to 11 children. By the time Margaret Cady had her last baby at the age of 44, the family had lost six children. In the early 1800s, proper medical care still lay far off in the future. Doctors did not have medicines to treat diseases, so babies and children died from measles, whooping cough, and scarlet fever. In 1830, a family with 10 children could expect that three or four of them would die while still young.

Fate seemed to frown on Judge Cady and his wife. In their day, families looked forward to having sons to follow in their fathers’ footsteps. Sons carried on their fathers’ work as well as the family name when they married and became fathers themselves. The young Cady children who died were all boys. Only one of Elizabeth’s brothers, Eleazar, lived long enough to go away to college. Eleazar was the pride of his father’s heart, and Judge Cady looked forward to his son’s return to “read law” in his father’s office.

Then Eleazar got sick and died. The Cady home fell into mourning. Again, Daniel and Margaret Cady had to bury a son, but first they laid out his body in a coffin in their parlor. Elizabeth looked back on these terrible days when she was an old woman:

I still recall, too, going into the large darkened parlor to see my brother, and finding the casket, mirrors, and pictures all draped in white, and my father seated by his side, pale and immovable. As he took no notice of me after standing a long while, I climbed upon his knee, when he mechanically put his arm about me and, with my head resting against his beating heart, we both sat in silence, he thinking of the wreck of all his hopes in the loss of a dear son, and I wondering what could be said or done to fill the void in his breast. At length he heaved a deep sigh and said: “Oh my daughter, I wish you were a boy!”

Her father’s words cut Elizabeth to her very soul. From then on, she set out to prove to her father that she was as good as any boy. She went to the stable and learned to ride the wildest horses possible. At school, she surpassed nearly every boy in her class and took home a school prize in Greek to show her father.

But no matter how difficult the task or how well she mastered it, Elizabeth could not replace a son. Judge Cady was a man of his times. He could think that it was only a pity that Elizabeth was a girl. Women had no place outside their homes. There was no need for a woman to go to college or learn a profession.

Elizabeth chafed under these rules that society had set down for her, but her brainpower kept on growing. She left home for school at the newly opened Troy Female Seminary, one of many secondary schools just for girls that sprang up in the early 1800s. There she continued her study of Latin, Greek, mathematics, science, and literature.

Elizabeth admired Emma Willard, her headmistress, who had founded the challenging girls-only school. Willard planned to prove that young women could study the same tough subjects as young men without hurting their health or ability to have babies, as some doctors feared.

Once Elizabeth finished school, she returned home to live a proper young lady’s life. As friends from school came and went, she enjoyed outings on horseback in the summer and sledding parties in the winter. Now referred to as “Miss Cady,” she took herself to her father’s law office, where she read Blackstone’s Commentaries and argued about them with the young men who worked as law clerks for her father.

Elizabeth Cady attended the Troy Female Seminary. Girls could not go to college.

Elizabeth Cady attended the Troy Female Seminary. Girls could not go to college.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Seneca Falls Historical Society

Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Seneca Falls Historical Society

Elizabeth Cady had strong opinions, especially about Blackstone’s views on rights for women. She and her sister Margaret also enjoyed competing with young men’s ideas. Nothing pleased her more than a long argument with them on women’s equality.

For Elizabeth Cady, the game was on, and she prepared by studying the books they read and the games they played. Only one goal was in her mind: “to make those young men recognize my equality.” She learned to play chess and was satisfied that, “after losing a few games of chess, my opponent talked less of masculine superiority.”

Elizabeth especially enjoyed the company of her brother-in-law Edward Bayard, who had married her older sister Tryphena. Edward enjoyed the company of Elizabeth and her friends. He challenged them to think deeply about what they had learned at school. He asked lots of questions, and when they answered, he challenged them with even more. They “discoursed” on law, philosophy, political economy, history, and poetry.

Together they read many novels. During long winter evenings in front of the fire, Edward Bayard read aloud from thrilling tales written by Sir Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, and Charles Dickens. Dickens’s popular books arrived chapter by chapter in magazines from England, “leaving us,” Elizabeth wrote, “in suspense at the most critical point of the story.”

Each year Elizabeth looked forward to her visits to Cousin Gerrit Smith and his wife. In a lovely autumn of 1839, before winter set in and made travel difficult, Elizabeth journeyed to the Smith estate in Peterboro, New York.

Gerrit Smith was a gentleman and a scholar. The Smiths had a house full of company, including a crowd of young men and women who liked to have fun. They didn’t know that Gerrit and Elizabeth Smith had several escaping slaves hidden away on their property. The Smith household was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

One afternoon, Gerrit Smith called Elizabeth and the other young women away from the parlor. He led them to the third floor of the house. There sat a young girl, age 18—she was an escaped slave who had run all the way from New Orleans. Elizabeth noted that she was a “quadroon,” which is a mixed-race woman who has three white grandparents and one African grandparent. Elizabeth recorded what happened next.

As a girl, Elizabeth Cady treasured the year’s three best holidays. As an old woman, she looked back on those days of joy and wrote about Christmastime. Stanton and her friends played blindman’s buff, but today it’s more commonly known as blindman’s bluff.

The great events of the year were the Christmas holidays, the Fourth of July, and “general training,” as the review of the county militia was then called. The winter gala days are associated, in my memory, with hanging up stockings and with turkeys, mince pies, sweet cider, and sleigh rides by moonlight. My earliest recollections of those happy days, when schools were closed, books laid aside, and unusual liberties allowed, center in that large cellar kitchen to which I have already referred. There we spent many winter evenings in uninterrupted enjoyment. A large fireplace with huge logs shed warmth and cheerfulness around. In one corner sat Peter sawing his violin, while our youthful neighbors danced with us and played blindman’s buff almost every evening during the vacation.

A game of blindman’s bluff.

A game of blindman’s bluff.

Now grab your friends and play a game of blindman’s bluff.

You’ll Need

Decide on the boundaries for your game and clear the area of obstacles like throw rugs or chairs.

Choose someone to be “It,” who puts on the blindfold. Turn It around several times. It then counts out loud to 25; everyone scatters until It says “Stop!” It wanders about, trying to tag players out. A player’s feet must not move, but the player is allowed to twist and turn to avoid being tagged. Play until everyone has been tagged—and until everyone has a chance to be It.

At last, opening a door, he ushered us into a large room in the center of which sat a beautiful quadroon girl about eighteen years of age. Addressing her he said: “Harriet, I have brought all my young cousins to see you. I want you to make good abolitionists of them by telling them the history of your life—what you have seen and suffered in slavery.”…

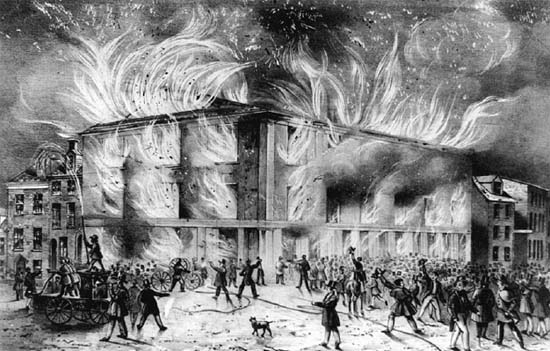

In 1838, Elizabeth Cady’s cousin Gerrit Smith was present at an antislavery society meeting in Philadelphia when a mob burned its brand-new building to the ground. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-1951

In 1838, Elizabeth Cady’s cousin Gerrit Smith was present at an antislavery society meeting in Philadelphia when a mob burned its brand-new building to the ground. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-1951

For two hours we listened to the sad story of her childhood and youth separated from all her family and sold for her beauty in a New Orleans market when but fourteen years of age…. We all wept together as she talked, and when Cousin Gerrit returned to summon us away we needed no further education to make us earnest abolitionists.

Among the visitors to Peterboro was a young man in his 20s named Henry Stanton. A keen abolitionist, the dark-haired, blue-eyed Stanton made his living on the lecture circuit. Believing that Henry Stanton was engaged, Elizabeth spoke eagerly with Henry about his experiences. She felt free of the awkward, tongue-tied nerves that young people sometimes feel when they meet an attractive person.

However, Stanton was not engaged, and he began to court Elizabeth. Not long thereafter, Henry Stanton asked Elizabeth to marry him. As she expected, her father stood firmly against the marriage. How, Judge Cady asked Elizabeth, could a lecturer without a real job expect to support a wife?

For a time, Elizabeth ignored her father’s questions, but she broke the engagement. Then, just as quickly, Henry Stanton made plans to sail to London for the World Anti-Slavery conference the next summer. Elizabeth did not want an ocean to roll between them, so she changed her mind and married Henry Stanton in May 1840.

Like Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady “obstinately refused to obey” her new husband, “one with whom I supposed I was entering in an equal relation.” Henry accepted this giant step away from tradition, and their minister dropped the promise to obey from Elizabeth’s marriage vows. Unlike Lucy Stone, Elizabeth did take her husband’s last name as her own.

The Stantons sailed to England, where both Elizabeth and Henry planned to serve as delegates to the antislavery conference. When they arrived to take their seats, they gasped in surprise. Their English hosts, many of whom were churchmen, refused to seat women as delegates to the convention. Elizabeth had to take a seat behind a low bar hung with a curtain.

The English ministers “seemed to have God and his angels especially in their care and keeping and were in agony lest the women should do or say something to shock the heavenly hosts,” Elizabeth Stanton scoffed. She wondered what the heroines of the Old Testament would have said about the conference. “Deborah … and Esther might have questioned the propriety of calling it a World’s Convention, when only half of humanity was represented there.”

Some of the world’s most influential women listened in the back section of the room—all were abolitionists. The Americans Angelina and Sarah Grimké were there, along with other famous reformers. Among the Englishwomen was Anne Isabella Byron, wife of the famed poet Lord Byron and a member of England’s upper class. Humiliated and chagrined as Stanton and these ladies felt, more than anything they scorned the shallow reasons men gave for separating them.

KIDS today spend their evenings far differently than young people in Elizabeth Cady’s day. Listen to how she spent them:

The long winter evenings thus passed pleasantly, Mr. Bayard alternately talking and reading aloud [Sir Walter] Scott… and [Charles] Dickens, whose works were just then coming out in numbers from week to week, always leaving us in suspense at the most critical point of the story. Our readings were varied with recitations, music, dancing, and games.

What do you do at night and on weekends? How much time do you spend with your family? Do you hang out together? Or do you spend your time on a computer or listening to music through earphones?

Here’s the challenge: Can your family turn off the TV, computers, video games, and smartphones after dinner—and all weekend—for a whole week? What can you do instead?

Brainstorm some ideas. Check out the activities in this book: play blindman’s bluff, perform in a readers’ theater, make an oil lamp, paint some china, or start a scrapbook. Read aloud together or host a tea party.

When the week’s up, think about what felt different and why. What have you learned about how you use your free time? What did you learn about spending time with others face-to-face?

As men debated on stage at the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1841, the women had to sit behind them and were refused a chance to speak. Library of Congress 1841 LC-USZ62-133477

As men debated on stage at the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1841, the women had to sit behind them and were refused a chance to speak. Library of Congress 1841 LC-USZ62-133477

One Quaker woman caught Stanton’s eye. The petite, bonneted Lucretia Mott, an American like Stanton, had journeyed to London with her husband, James. Lucretia Mott was a full generation older than Stanton, and Stanton admired the older woman’s wisdom. As a couple, James and Lucretia Mott had made a name among abolitionists, and Mott also spoke out on women’s rights.

During their days in London, Elizabeth Stanton and Lucretia Mott discovered they were of one mind—they thought that women deserved to be treated equally with men. As the convention adjourned, a new idea buzzed among the participants: “It is about time some demand was made for new liberties for women.”

A teacher when she turned 16 in 1809, Lucretia Mott discovered that she was paid half of what a man made. To Mott, such treatment was a sin against God. “[T]he injustice of this was so apparent that I early resolved to claim for my sex all that an impartial Creator had bestowed,” Mott wrote.

She went on to become a Quaker minister, free to speak when Quaker men and women gathered to worship. However, when Lucretia Mott chose to speak to men in public in Philadelphia about the evils of slavery, a mob burned down the building where she lectured.

Mott’s speeches about slavery to mixed groups of women and men went too far, even for her broad-minded Quaker friends. But onward she went, even as she raised six children and hid escaping slaves in their home.

Mott was a stay-at-home mother, like most women in her day, but she resolved to continue improving her mind. The sewing machine had yet to be invented when her children were small. When Mott did the family mending, she “omitted much unnecessary stitching and ornamental work” to squeeze in more time to read.

Lucretia Mott pictured in her Quaker bonnet. Library of Congress rbnawsa n3028a

Lucretia Mott pictured in her Quaker bonnet. Library of Congress rbnawsa n3028a

Stanton and Mott walked home arm in arm, as friends did, sharing the events of the day. It was a remarkable moment for Stanton when she and Mott “resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home and form a society to advocate the rights of women.”

That convention took place eight years later.

IN 1847, the Stantons moved to Seneca Falls, New York, near the tip of Cayuga Lake in the Finger Lakes. By now, Elizabeth was the mother of four children. As was always the case with Henry Stanton, he was too busy with work to help with the move. Elizabeth Stanton, her sister, their five children, and seventeen trunks made a two-day trip by train from Boston. The whole time, Stanton worried that one of the little ones would fall off the platform into the path of a moving steam engine.

She took charge of their new home, a rundown place just outside Seneca Falls, where she hired workers to repair the building. Seneca Falls was not Boston, as Stanton soon realized. She missed the big city with its exciting, reform-minded women and men.

Here in Seneca Falls, a blighted mill town, she could not find good servants to help her with her children, and Henry was always away working. Stanton also realized that she and her husband could easily have a big family, but she was the only one at home to care for their children.

To keep a house and grounds in good order, purchase every article for daily use, keep the wardrobes of half a dozen human beings in proper trim, take the children to dentists, shoemakers, and different schools, or find teachers at home altogether made sufficient work to keep one brain busy as well as all the hands I could impress into the service.… I suffered with mental hunger, which, like an empty stomach, is very depressing.

Things got even worse during the warm weather. Seneca Falls had mosquitoes, and all the children caught malaria after getting bitten. They were sick for three months with chills and fevers. For better or worse, Stanton had to set aside her personal battle for women’s rights to take care of her children.

Then Stanton received a welcome invitation to tea. Lucretia Mott was visiting her Quaker friends and relatives in a nearby town. On June 10, 1848, Elizabeth hopped on the train and went to Waterloo for a tea party with four others, including her cousin Elizabeth Smith Miller. This group of “earnest, thoughtful women” listened to her frustration.

“I poured out that day the torrent of my long accumulating discontent with such vehemence and indignation that I stirred myself as well as the rest of the party to do and dare anything,” Stanton said later.

That very night, they wrote “the call.” The announcement of a Woman’s Rights Convention was published in the Seneca Falls Courier the next day.

Stanton and another woman, Mary Ann “Lizzie” McClintock, met again before the convention. Taking pens to paper, they wrote a rough draft of a document they called “A Declaration of Sentiments.” In clear writing, the two women made their case for women’s rights. Their model was close at hand: Stanton and McClintock used the Declaration of Independence as the starting point for their own declarations.

CLEVER suffragists knew that one-on-one meetings would help recruit women to “the cause.” Often such gatherings took place in their homes, where women could meet each other in comfort and speak openly. Suffragists often did their work while sharing cups of tea and something sweet.

Invite some friends and have a tea party to talk over important issues in your lives. Set a pretty table, round up a teapot and some cups, and add your favorite sweets. Here’s how to plan your party. If you wish, serve the suffrage cake shown on pages 59–60.

You’ll Need

MAKING PREPARATIONS

Set the table with a pretty cloth. Add a simple table decoration—flowers in a vase, a pretty plant, or even a gathering of colorful stones or shells in a bowl.

At each place lay a folded napkin, a dessert plate, a teacup and saucer, a fork, and a spoon. Just before your guests arrive, place serving plates filled with goodies on the table. These will be passed from guest to guest. Add the sugar bowl, a small pitcher of milk, and a plate of lemon slices along with a small fork.

MAKING TEA

To make hot tea, first be sure your teapot is clean. Warm the pot by filling it with hot tap water and set it aside. With an adult’s help, fill your teakettle and set it on the stove to boil. The tea water must come to a full boil.

In the old days, people poured hot water over tea leaves right in the pot and then poured the tea through a strainer into their cups. Today, we use teabags—one teabag per person, plus one for the pot.

Now IT’S TIME TO PARTY

As your guests arrive, give each one a pencil and note card. Ask each guest to write down one topic that he or she would like to share with the group.

Pour and serve the tea to your guests in their teacups. Offer them sugar, lemon, and milk. (Warning: don’t use lemon and milk together— the lemon will curdle the milk and make a mess.) Pass around the plates of goodies, and invite your friends to help themselves.

As host, it’s your job to keep the conversation going. Ask your guests to share the topics they wrote on their note cards. Be sure that everyone has had a chance to share by the time your tea party is finished.

What kinds of topics did you discuss?

On the morning of July 19, 1848, a crowd packed into the pews of the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls. Visitors came from all walks of life: educated women like Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Stanton, others who were not as well schooled but just as curious, some open-minded men, and a group of country girls led by a young glove maker named Charlotte Woodward. Like Stone, Woodward did piecework (sewed gloves by hand at home) on the family farm, and, like Stone, she hated the thought of turning her hard-earned income over to the men in her family.

When the meeting opened on July 19, 1848, convention goers were greeted with Stanton and McClintock’s Declaration. Its 942 words would rock their world.

ELIZABETH CADY Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments summed up every fact that made women second-class Americans. Stanton echoed Thomas Jefferson’s stirring Declaration of Independence against England, but she made his words the words of women everywhere.

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness….

The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise. [Women could not vote.]

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice. [Women obeyed laws they did not help to write.]

He has withheld from her rights which are given to the most ignorant and degraded men—both natives and foreigners. [Men denied women the same rights held by uneducated men who were not citizens.]

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns….

In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master….

He has so framed the laws of divorce… as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women….

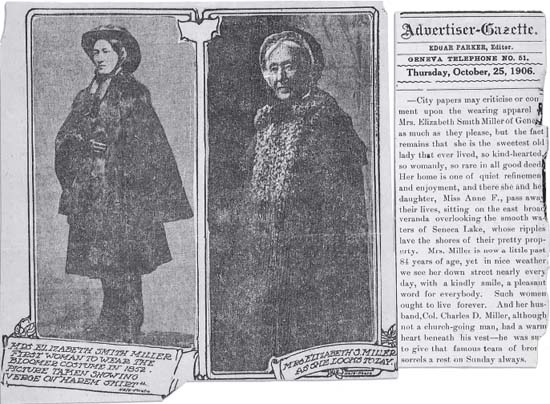

You might think that scrapbooks are a modern hobby, but pasting pictures, letters, and newspaper clippings into albums was popular among suffragists and others in the 1800s. The Library of Congress—the United States’ national storehouse of books, photos, music, and more—has a repository of suffrage scrapbooks. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousins, Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller, filled seven albums with mementos of their work for the vote. Go online and watch a video called “Catch the Suffragists’ Spirit:

Elizabeth Smith Miller pasted a newspaper clipping about herself in one of her scrapbooks. Library of Congress rbcmil scrp7000601

Elizabeth Smith Miller pasted a newspaper clipping about herself in one of her scrapbooks. Library of Congress rbcmil scrp7000601

The Millers’ Suffrage Scrapbooks” at http://www.loc.gov/today/cyberlc/feature_wdesc.php?rec=4839.

Now it’s your turn to make a memory. Create a scrapbook in which you can store special mementos from your life. To keep things easy to move around, use something you’re familiar with, like a loose-leaf notebook.

You’ll Need

To begin, fill your scrapbook with paper. Using the piece of notebook paper as a template, punch holes in the heavyweight paper. Or use a three-hole paper punch if you have one.

Use the card stock to make pocket pages. Three pieces of card stock make two pocket pages. Start by folding one piece of card stock in half, as shown. Cut along the folded line. Place one full piece of card stock on your work surface. Place a half piece on top, matching three sides.

Cut a piece of masking tape a bit longer than the width of the card stock. Lay the tape upside down on your work surface. Now place the bottom of your pocket page along the tape so that it’s half off, half on, as shown. Flip the tape over to the front. Use your fingers to gently seal the tape along the bottom edge. Trim the ends of the tape even with the card stock.

Repeat the procedure with the sides of the pocket: tape, flip, and seal. Trim the edges into a neat square. Now run your fingers along all the taped edges.

Punch three holes in your pocket page to fit the rings in your scrapbook. You’re ready to fill your pocket page with memory-making items!

Finally, make a cover for your binder. Use pictures, cutouts, glitter pens, small flat trinkets—you can even make a collage. Let your imagination fly! Slip your artwork into the plastic cover on the front of the binder.

When you open this scrapbook 50 years from now, what memories do you want jumping out at you? Items that evoke these memories are the ones you will want to add to your project. By using a binder, you can arrange your memorabilia any way you wish.

One more thing: you get much of your information from the Internet. How are you going to preserve your “e-memories”? You might have to print out e-mails or download copies of articles you read online. There might also be CDs or DVDs for you to include—maybe a thumb drive, too.

Could the Miller sisters ever have imagined that you’d read their scrapbooks by looking at an electronic device? Find them at http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/suffrage/millerscrapbooks. Click on “Scrapbook” on the left-hand side.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single, and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government….

Stanton listed a long series of complaints: women’s lack of good jobs, poor pay, no chance to go to college, and no opportunities to serve as ministers. Then she finished with a flourish.

The outlandish costume that enraged men was invented by Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s cousin Elizabeth Miller. However, “bloomers” took their name from a woman who adored wearing them—Amelia Bloomer.

Bloomer started her reform work as a member of the temperance movement, campaigning against the evils of alcoholic drinks. She sat in the audience when Stanton and other women opened their battle for women’s suffrage at Seneca Falls in 1848.

Amelia Bloomer proudly wore bloomers, which were named after her. Seneca Falls Historical Society

Amelia Bloomer proudly wore bloomers, which were named after her. Seneca Falls Historical Society

Years ahead of most women in her views, Bloomer launched the Lily, a newspaper for women with short stories and articles about temperance and women’s rights. Bloomer, who was fiercely independent, wore her “Turkish trousers” everywhere. They were comfortable and convenient. She didn’t have to hold them up off muddy streets.

Outraged spectators accused her of “mannishness.” Bloomer spat back, “I feel no more like a man now than I did in long skirts, unless it be that enjoying more freedom and cutting off the fetters [chains] is to be like a man.”

Bloomer married a dedicated Quaker lawyer who believed in women’s rights. She was devoted to him, and when he decided to move west, she sold the Lily and went with him. Nonetheless, all her life Bloomer fought Victorian views about womanly duties in marriage.

Bloomer asked pointed questions to anyone within earshot. Why was it a woman’s “duty” to obey her husband if God had created them equal? If women were expected to raise children to be good moral adults, then why did the law forbid mothers any legal authority over their own children?

When Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter Harriot was born, her mother wrote words of joy in having given birth to a girl. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-48965

When Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter Harriot was born, her mother wrote words of joy in having given birth to a girl. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-48965

Now, in view of this entire disfranchisement of one-half the people of this country,… we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.

The call for women’s suffrage—granting women the right to vote—shocked America’s reformers. Only one man at Seneca Falls, the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, agreed with Elizabeth Stanton’s demand.

For others, both women and men, the thought that women might cast ballots along with men was going too far. Lucretia Mott fretted. “Why, Lizzie, thee will make us ridiculous,” she said in the Quaker way of addressing a friend.

Mott was correct, as “Lizzie” knew. The newspapers made fun of Stanton’s ideas. All the journals from Maine to Texas called her thoughts “ridiculous.” Stanton later wrote about what happened after the Seneca Falls convention:

[S]o pronounced was the popular voice against us, in the parlor, press, and pulpit, that most of the ladies who had attended the convention and signed the declaration, one by one, withdrew their names and influence and joined our persecutors. Our friends gave us the cold shoulder.

Stanton took criticism well. When her cousin Elizabeth Miller designed a new “costume” for women to wear, Stanton eagerly put one on. Her bloomer outfit caused tongues to wag, but Stanton praised its comfort and convenience. She wore bloomers for several years. The costumes caused so much fuss that suffragists finally gave them up. The women decided that there were more important things to accomplish than dress reform.

The bold gathering at Seneca Falls had sparked an idea. Another women’s rights convention took place in Rochester, New York, the next month. After that, women in state after state hosted their own meetings to continue their talks. From one small tea party, a nationwide interest in women’s suffrage began to grow.

With so many children to care for, Stanton couldn’t travel to meet with other women’s rights activists. Ideas flowed from her mind easily—but what wouldn’t come easily was leaving home. Clearly, Elizabeth Cady Stanton needed help to take her beliefs on the road.