Philippe’s lessons of darkness

FRANÇOIS WARIN

The African adventure I hereby set forth to relate had initially been told in the halo of Conrad’s tale. First published in the Journal Lignes, in memoriam to Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, this piece originally bore the Conradian title, ‘Heart of Darkness’.1 In the course of this African adventure, Philippe and I faced what for both of us proved to be an absolutely harrowing experience when, at the culminating point of our journey, we were given the opportunity to witness a Dagara funeral ceremony.2 This ceremony, similar to those enacted by the Lobi people, testified to this knowledge of death [savoir de la mort] as Philippe called it, a knowledge to which, in our Western hubris and self-conceit we have now become fully foreign. Five years later, when I was confronted to the Rwandan Genocide, the discovery of Philippe’s reading of Conrad, L’horreur occidentale, was particularly beneficial to helping me think through the emotional shock generated by this apparently African horror. ‘The Horror of the West’, then, allowed me to initiate, in the absence of Philippe this time, but in his textual company nonetheless, another reading of Heart of Darkness. It also enabled me to attempt a second, more subtle and more difficult navigation towards this unbearable outside whose extimacy has now become apparent and is there for all of us to face. It is at this stage that, for the occasion of this volume, I have added a philosophical coda to the first, more biographical and personal text.

The darkness of a sacrificial heart

The true is hateful. We have art so as not to vanish through the bottom of things—foundered by truth.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente

This is the title that spontaneously comes to my mind as I attempt to revise this essay in honour of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe. First of all, because it was Philippe who first advised me to read Heart of Darkness, as I was just about to be embarked on a journey to West Africa. Indeed, what better introduction to Africa than Joseph Conrad’s most celebrated tale? And what better guide than this literary text to speak about Philippe, all the more so from an experience I had been given the honour to partake in as a privileged witness? It is, in fact, on the African continent that I have learnt to really know and love Philippe. With Claire, his wife, he had come to see us several times.3 Every time, his coming was inscribed in what was, for me, an entire horizon of theoretical and emotional questions, questions that had long been on his mind and that were centred around the question of myth. This question, undoubtedly inherited from an old, twisted and conflicted Romanticism, often led us to look in the same direction and to find ourselves on the same ground, a ground that was, for both Philippe and myself, in more than one sense, something like a native soil.

When I first met him in 1968, Philippe was already wrestling with the brief and opaque Remarques sur Oedipe et Antigone4 as well as with the onset of modern atheism. For me, Philippe has always remained the thinker who has attempted to respond to this work of mourning (Trauer), to this categorical turning away from the divine, that was, already for Hölderlin, tragedy as such (Trauerspiel). Or, and this is practically the same thing, the thinker who, his body notwithstanding, has given himself up during his entire life to a severe and uncompromising critique of the problematic of presence and, consequently, to a critique of every attempt to re-mythologize Hölderlin. In a way, it is in contrast to his very protestant attitude towards these Western questions that I understand Philippe’s relation to both Africa and Africans, a relation revealing of a tenacious force, as well as of an abyssal obscurity against which he was set up hard. From the moment he arrived on the African continent, however, everything appeared to have been inversed. To speak like Schelling, the eternal ‘yes’ substituted itself to the eternal ‘no’, gentleness to force, understanding to sternness or love to anger.

And yet, in the case of Philippe, this had nothing to do with a return to a form of primary naïveté. He never fell into the trap of this kind of ‘primitivism’ or, as Sally Price would have called it, hard primitivism,5 a primitivism that Conrad’s Heart of Darkness contributed to constitute. Rather than denouncing the stereotypical representations of Africa still operating in Conrad’s tale, as Chinua Achebe has famously done, it would be more productive to consider the tale from the more ambivalent angle of primitivism. As Heart of Darkness makes clear, primitivism assumes that the future of humanity is to be found in the past. It thus relies on an inversion of the ideology of progress and emphasizes at least two points. First, a generalized retroversion: from this perspective, the symbolic ascent up the river Congo is an ascent that is not only spatial but also temporal; it brings us back to what is most ancient and archaic, to the ‘unconscious’ and the ‘prehistoric’. In a sense, this retroversion constitutes the structuring form of the novella as a whole. And second, the identification of the ‘savage’ with the ‘magnificent’: in the context of hard primitivism this identification stretches to include an avowal of a fascination for the ‘abominable’ and the ‘hideous’. From this perspective, then, under the rags or the varnish of culture that masks what is essential, the origin would always remain present. Moreover, the memory of the vital, foundational ‘savagery’ is considered to be the origin of everything that is synonymous with greatness. All these historical-empirical schemes are nonetheless subverted by Philippe’s analyses of African art. For Philippe, in fact, what is thrilling in the African ‘incomprehensible frenzy’ (96) – a frenzy which is of course far from limited to Africa – is not so much ‘the thought of their humanity’ (96) as is still the case for Marlow, but the opposite. African art, Philippe writes – in the context of aesthetic considerations that make his anti-racist inclinations clear – represents not so much the ‘human(ity) in (of) man, but what we could risk calling the (in)human(ity) in (of) man [l’(in)humain dans (de) l’homme]’ (197). For him, at the heart of these artistic representations of man is a secret intimacy that opens up to a pure outside, an extime that places humanity in an ecstatic state. Here is how he continues his discussion of primitive art in general and in Lobi art in particular. The echoes with ‘The Horror of the West’ are clearly audible:

(In)humanity, here, is not inhumanity, that is, the loss of humanity or its negation. On the contrary, it is the most secret heart [le coeur le plus secret], the most sheltered side of humanity . . . . It is not a sort of whatever ‘transcendence.’ Augustine calls it God, but he says: interior intimo meo, what is most interior than my intimacy itself. And we can guess that this intimacy of intimacy, beyond intimacy, opens onto a prodigious exteriority, a pure outside that places humanity in an ecstatic condition [qui extasie l’humain] . . . a way of figuring . . . extricated from the eidico-spiritualist constraint that preserved philosophy.6

*

Philippe knew Michel Leiris well, and he strongly advised me to read L’Afrique fantôme.7 As an homage to Leiris, he had entitled a conference that he had given in Benin, in 1991, ‘La philosophie fantôme’.8 And, to me, Leiris’s lucidity about Africa is in fact what Philippe’s irreproachable probity generally evokes. Coming from this avatar of Romanticism that is Surrealism, in Africa, Leiris did not cease to discover an intimate fissure or wound inside himself: he discovered an insuperable difference that divided him from this mythic continent, from this land of origins which, for him too, was the land of trances and possessions. ‘A sinister thing it is to be a European’ he notes in his journal upon returning from this failed initiatory journey that had been the Dakar–Djibouti mission (2 September 1931).9 For Leiris, what was at stake in this physical journey was a metaphysical journey, somewhat like in Heart of Darkness, where the ascent of the river Congo is metaphorically associated to ‘travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world’ (92). And yet, the origin proved to be both frightful and terrifying; eventually, it ended up retreating and disappearing evermore. This is exactly what happened to Africa: it remained indistinguishable from the phantoms and projections of that European in need of redemption he was. His Africa remains, in all respects, L’Afrique fantôme. In a slightly displaced form, we find the same disillusioned theme in Philippe’s conference on Africa, a theme that will be even more sharply brought into focus in ‘The Horror of the West’. As he demonstrates, the domination of the West is both definitive and complete. As such, it is identical with the becoming-world of philosophy. From the bottom of that prison which is ours we can thus only glimpse what this continent has been prior to the domination of the West: we can only ‘guess at its fragile image (from the) outside’.10

‘Lucidity is the wound which is closest to the sun’, wrote René Char, at the time of Feuillets d’Hypnos.11 How could one best translate what constitutes the entire difficulty, as well as the entire ‘truth’, of Philippe and his ‘emotion of thought’? The kind of lucidity that makes us see the irremediable wound of separation, that prevents us from still being pious is, paradoxically, the tracing of the vanishing gods. And this is the only proximity that is emotionally thinkable, as well as possible, in relation to this ‘sun’, which, no more than death itself, cannot be faced directly.

This intense and complex relationship with Africa started very early and via the intermediary of an artistic object. Philippe, who had borrowed Michel Leiris’s and Jacqueline Delange’s book on African art (printed in the collection directed by André Malraux), always passionately loved what Europeans call primitive or primal art. As soon as he had a bit of money, during a visit to Paris, he purchased a Bambara Tyi Wara helmet crest [cimier]. As his brother Dominique recently told me, he was, at the time, only 13 years old. The first letter that I received from him was a passionate note in which he thanked me for the small idol made out of clay that I had left, during his absence, on his desk, in Strasbourg. In a text that still echoed the lament [plainte] of the exiled thinker, he said how deeply he had been moved:

I am embarrassed [gêné] and very happy at the same time: [I feel] a connection that I am incapable of expressing . . . . I am all the more touched as it is very beautiful and, let’s say, moving. This touches, thus, very precisely, on what restrains me [ce qui me contraint] because the proximity risks to be excessive and unbearable [insupportable] in relation to the preservation of too great a distance. The presence of this object will reanimate this wound. There are few things of which this can be said.

And how many times in the years that followed did I bring back from Africa some of the last relics of primitive art, associated generally with the cult of the dead (see Fig. 6.2 below). What emotion every time I saw, in his apartment in Paris, all these statues carefully set on top of an old fireplace, and all these masks hanging on the walls!

*

To be sure, this African path had long been opened. Philippe had entered politics during the Algerian War, and it is the anti-colonial struggle that had permanently structured him. Both of us could thus maintain friendly relations with Africans, relations free from all kinds of prejudices. What we had learned from Conrad’s tale was now given to us to experience: Africa was, for us, the return of the real that unmasked the Western pretention to ‘civilize’ indigenous people. As always, colonization and the ‘civilizing mission’ it entails had proved to be a total failure. This also means that there is always, at the heart of each of us, a Mr Kurtz, ready to be awakened, a Mr Kurtz intoxicated with power and possessed by a logorrhea as sinister as it is vain, by an ideology that places colonization – for all the ‘missionaries’ and ‘pilgrims’ – in the service of the Idea. Kurtz, this Belgian with a German name is indeed a ‘hero’ who is, quite literally, swallowed up by the colonial ‘muddy hole’ (150). As some scholars seem to think, Kurtz is also a shortened version of Conrad’s own name (Korzeniowski). Hence he is a double: his double, but also our double – and the incarnation of the West: ‘All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz’ (117). Kurtz collected ivory in the same way others would collect works of art.

I have never seen anyone respond with such a vibrating intensity as Philippe did to the spectacle that we were given to witness during our somewhat adventurous expeditions in the savannah. I recall the happiness the prodigious African gaiety roused in us, the same gaiety that had also fascinated Nietzsche. But I also recall the simple and warm hospitality whereby we had always been welcomed. I remember in particular the powerful emotional effect upon Philippe when, during his first African voyage, we visited a Dogon village at the far eastern extremity of the Bandiagara cliffs: ‘One should write a book, write something’, he had told me. The mythic isolation in which the Dogons live has always triggered this kind of enthusiasm: ‘Exceptional religiosity; the sacred swims in every corner of life’, writes the honest Leiris.12 It has also generated an entire onto-mythology: that of the French school of anthropology, a school for which myth, and myth only, had been the royal road to study these people’s identity and history. The Dogons are somewhat like the Pre-Socratics: had their discovery not been for us a bit like what the discovery of a Greece before Socrates had been for Nietzsche or Heidegger?

Upon his return to Europe, in order to describe his stay in Africa, Philippe spoke of a true mystical experience. In Africa, we had not felt the need to speak of this feeling of transport, this happiness, at all. And, besides, in which language could we have done so? Later, I discovered that my feeling had been confirmed, in a precise way, in an interview where Jean-Christophe Bailly asked Philippe about his furtive, but nonetheless essential, contacts with Africa.13 In this ‘kind of immense night that is Africa’, he said:

we were crushed by a feeling of . . . of sacredness [sacré] . . . . In this immense African darkness (it was cold, as always during the night over there, it was windy and there were those noises . . . .) we were haunted, haunted, which means inhabited [habités] too . . . and I have felt, in a very, very impressive way, this feeling of . . . this feeling of, yes, of sacredness [sacré]. We had the impression to be facing what, by definition, is not, what can only be thematized under the name of void. This is why it is very difficult to write about this. One cannot say this, but all of a sudden, one had the impression of being in the presence of what is other [en presence d’autre], an otherness which is not one thing [une chose]—one cannot even say ‘something other’ [autre chose]. There is a form of vacillation [bascule] that has taken place. . .14

*

Among the strongest experiences that we underwent, I recall those Dagara funerals that we chanced upon. Not unlike Conrad’s Marlow, it seemed to us that this time we had ascended the river, travelled towards the origin, in order to be finally confronted with the horror – the horror of death. The great violence of this ritual had strongly impressed us: the display of the deceased, sitting for three days on a podium, the ritual laments and the heartrending cries of an entire village ready to confront the transgression of death. In reality, the Africans had turned death into a holy day; they could also dance in front of this ‘dark sun’, as Georges Bataille would have put it, or in front of the ‘Open’ [l’ Ouvert] that is at the foundation of things, as Lacoue-Labarthe would have said. But along with its violence, what we were also given to think and feel was the great wisdom of this ceremony, a cathartic or purgative ceremony, now ingeniously erased by our Western ‘techniques of death’ whose function is to prevent us from facing the horror of la disparition.

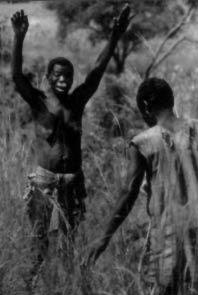

This picture (Fig. 6.1), taken by André Vila in 1955,15 is to my knowledge the only existing photographic testimony representing the funeral cries, or laments, as they take place in a ritualized form, in Africa, among the Lobi people of Burkina Faso. In the midst of the savannah, a crying woman wearing a labret on her upper lip, tragically stretches out her naked arms, in an attitude that is simultaneously one of imploration and of terror.16 In front of her, an immobilized man seems prostrated, hypnotized, completely paralysed by a horror that is without name.

Figure 6.1 André Vila, Lamentations funéraires lobi, 1955.

This Lobi statue (Fig. 6.2) is also intimately associated with the cult of the dead. Such statues are sculpted in order to ward off a destiny of misfortune, but also in order to signal, or take upon themselves, an unbearable and unspeakable pain. Certain statues, like the one represented here, characterized by an extreme tension and concentration, reproduce the attitude of these funerary lamentations. In its making, the sculptor alone, without mediators, is exposed to occult forces and to malefic geniuses that can, at any time, strike him with madness or disease. His task is to attempt to exorcise fear and to help humans face the ever-present menace of death.

Figure 6.2 Lobi sculpture. Lamentation funéraire, collection J. L. Despiau, photo. F. Warin.

Figure 6.3 André Vila, Funérailles lobi, 1955.17

If, as Bataille puts it, ‘the seriousness of death and pain is the slavery of thought’,18 then, it is likely that slavery will remain, for a long time, our common burden. Here we find ourselves, ‘ceasured’, in a state of mourning, exiled from cults, as well as from myths and rituals. Unlike these Africans, we shall remain fully incapable of expulsing, through ritual laments, the excessive pain that the death of our friend, Philippe, provokes in us. We will certainly have to learn to live with this void, but also with the memory of someone who chose – deliberately, there is no doubt – a brief life.

Coda: The darkness at the heart of genocide

[N]ever, never before, did this land . . . appear to me so hopeless and so dark, so impenetrable to human thought, so pitiless to human weakness

Conrad, Heart of Darkness

When, some time ago, I was invited to speak after the screening of a film on the Rwandan Genocide,19 I could not help but think about ‘The Horror of the West’. Like so many others, I was horrified: my spirit was broken by the unspeakable cruelty of this event, and I asked myself in which language I would have been able to speak. Then, suddenly, it appeared to me that the only mode through which one could approach it was in the mode of the Lessons of Darkness, a canonical text from the Catholic Liturgy which, at some level, equally informs Philippe’s reading of Heart of Darkness.20 The Lessons of Darkness are undoubtedly lessons in the sense that they are a form of teaching. But, above all, they are a funeral hymn, a hymn not so much turned towards kenosis but, rather, towards an unthinkable black hole.21 From the horror of sacrificial death to the horror of the genocide, I felt like I was continuing, in the company of Philippe’s thought, our African adventure into what Conrad called the ‘heart of darkness’. But, this time, in Philippe’s physical absence, and under omens more terrible than ever before. As it was also the case in Conrad’s tale, under the ‘savage clamour’ (105) of nature lay hidden an artifice and an abyss of another, more intimate clamour that was going to reverberate and resonate without end. Conjuring with a stubborn degree of mimeticism what, for lack of better words, I shall call absolute evil [l’absolu du mal] – and this in the very year that marked the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the crushing of the ‘Nazi barbarity’ – this genocide, in which to varying degrees ‘we’ were implicated belongs, in full right, to what Philippe calls ‘The Horror of the West’.

As we know, Heart of Darkness tells an initiatory journey whereby the protagonist/narrator of the tale, Marlow, ascending the river Congo, travels in quest of the origin in order to finally find himself face to face with the horror of Kurtz’s sacrificial rites. But what exactly is the vertiginous horror to which Kurtz, this artiste maudit avatar of Rimbaud, eventually capitulates? What is the horror that contaminates all those who approach him? As Lacoue-Labarthe puts it, it is not so much ‘the de facto horror of savagery’, (119) as the horror of the Thing or la Chose: the Lacanian name for the ‘malignity of being’ discussed by Heidegger, but also the malignity Georges Bataille – a figure obsessed by the horror of sacrifice – experienced at the time of Acéphale.22 The Thing is not some-thing, a being among other beings but, rather, no-thing [a-chose], an unspeakable void, the yawning abyss of chaos itself, the horror that is at the ‘foundation of things’ as Chardonne says. Or, alternatively, the Thing is the absolute lack of foundation [sans-fond] that allows us to touch the Real. It is that which, by definition, cannot be expressed and, perhaps, it is also that which motivated Philippe’s silences. ‘The horror’, he says – and we shall verify this in the precise case of Rwanda – is, indeed, ‘of the West’ (italics added) which also means that the horror is the West itself, that is, the West that defended itself from the fascination with the Thing by constituting a techne that works as a dangerous supplement and the West that defended itself through a technical and colonial inspection of the totality of the planet. By instituting the modern subject that produces and realizes itself, the West has been the only ‘civilization’ that could give birth to a new form of evil, a devastating and characteristically modern evil. And if it is true that, in the case of Rwanda, those who looked into the darkest side of evil may have been the Africans, it is equally true that they were subjected to a properly modern form of evil, a radical evil that is inextricably tied to the name of Auschwitz. This evil, as Philippe put it, ‘cesured’ our own history. This evil does not come from elsewhere; it is wanted by man himself. This evil has no meaning; it is a form of evil that defies representation and that is beyond reparation.

‘The horror! The Horror!’ These are the only words that one of the main witnesses could find, upon his return from Kigali, as he was interrogated by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), at the very beginning of the genocide.23 These words obviously echo Kurtz’s last, dying words, as he looked, one last time, into that abyss of darkness, which is his heart: ‘“The horror! The horror!”’ (149). And, indeed, what closer re-enactment of Kurtz’s atrocities than the Rwandan genocide? The Hutus would align children in their schools in order to cut them up with an axe or crush them under the blows of their clubs. In some instances they would give the bodies of the Hutus opponents (the first victims) for pigs to devour . . . The furore, the unchained rage, the complacency in sheer atrocity put us in the presence of an outbreak of hatred that exceeds the pure malice of human action. As Heidegger puts it, this hatred relies on ‘the malignity of furor’ that is at the heart of being itself.24

When evil transgresses a certain boundary, as Kurtz at the heart of the jungle also experiences, moral categories seem, indeed, to lose their pertinence. Evil is then liberated from human intentions; it becomes autonomous and organizes itself as a system that transcends humanity and becomes exterior to it. Its malignity without boundaries, its virulence and destructive frenzy [frénésie], as Isaiah also puts it, becomes, then, capable of ‘destroy[ing] the foundations of the earth’.25 The enigma, as we see it, is all here: like Kurtz, we are capable of producing a blind evil, an unpredictable evil that goes beyond us, and that retrospectively presents itself as a fatality. And yet, we, Westerners, are nevertheless responsible for it, if only because we could have prevented it from happening. Among those who partook in the Rwandan genocide are those who realized in what kind of infernal spiral, in what kind of exterminating vortex, they had been progressively caught up. They got carried away and none could escape this ‘dynamic of the Devil’. As they testify: ‘you cut up so many of them that you can’t even count them; it is Satan that has pushed us to the bottom of ourselves’.26 While saying this, they appear to be less devastated than overcome [dépassés], transported by an incomprehensible effect of excitement and amplification, an uncontrollable effect that resonated deeply with unspeakable actions, actions beyond understanding, that inspire anger as well as a certain sense of compassion. The sombre magnificence whereby Kurtz plunges into death reminds us that there is nothing prosaic about evil; evil is not of the body but of the spirit.

Genocide, this hybrid word with a double root, both Greek and Latin, is of recent formation (1944). It is now used everywhere, in those languages that founded the voracious West, a West that has now swallowed up the entire world. Despite revisionists’ denials, what has taken place in Rwanda undoubtedly belongs to the category of genocide. That is, to the destruction of a genos, of a population deemed guilty from birth. This is not simply yet another massacre. A genocide is indeed an effect of a project concerned with the extermination of a race, a project instituted by the State – that is, a project in the service of what Conrad already called an ‘idea’: ‘What redeems it is the idea’ says Marlow, ‘the unselfish belief in the idea – something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to . . .’ (51). Philippe would have said that this idea proceeds from what he calls techne, that is, knowledge as determined by the Greeks. This techne is endowed with an unequal power; it has been capable of assimilating all forms of knowledge coming from elsewhere; it is a form of knowledge that will end up by being determined as power and that will accomplish itself in the lure of the colonial and technical scramble for the entire world. And, as Philippe also reminds us, that which deploys the effects of this techne is what the Greeks called logos, that is, a discourse, an argumentation, a plan, a logistics. . . We should not forget that those who have assumed the control of this logos are intellectuals or, to speak plainly, ‘philosophers’ – figures always in quest of power. As it was already the case in Conrad’s Congo, in Rwanda, those who planned the horror and who sent people to ‘do the work’ on the hills were professors, journalists, lawyers, politicians – figures who, as the manager in Heart of Darkness puts it, ‘have no entrails’ (74). Here, words and actions have been strung together, and it is language – the realm where Kurtz, this hollow man who is also a journalist, excelled – that has been the other side of a double-edged machete. The weapon of this recent genocide, which was initially taken to be only a rural and artisanal phenomenon, was of course the machete, but also, and perhaps even more so, the radio: the most powerful and dangerous media, the mass-medium that penetrates without restraint into the profound intimacy of people. This medium will realize the ‘total mobilization’ (E. Jünger)27 of the forces of the State and feed, in a continuous stream, the genocidal frenzy.

As Conrad’s descriptions of the horrors of colonialism with its continuous stream of greedy devils craving for ivory already make it clear, both time and preparation are necessary to set the genocidal machine in motion and to transform an entire country into a slaughterhouse. The ‘pretty rags’ of ‘principles’, to borrow Marlow’s formula, ‘fly off at the first good shake’ (97). Each country can then give way, in all impunity and serenity, to ‘aggravated murder on a great scale’ (50) and, while following blindly white forms of Western will to power as a model, hope for a general ‘extermination’. And, indeed, the efficacy of this machine of death has been impressive. The Hutus only needed one week in order to actualize ‘their’ project and to engage in an ‘extermination plan’ that was among the fastest (from 800,000 to 1 million deaths in 3 months) and had the highest daily death rate.28

Notice that the critical state of a country plunged in a civil war does not explain these massacres, insofar as they were perpetuated outside of a combat situation. Women were, indeed, among the principal victims of these horrors. They were persecuted, raped, massacred, even when pregnant. Newborns were burned alive, smashed against walls or simply abandoned at places of carnage. Machetes were used to open the wombs of women, ‘like bags’, as it was said,29 and the murderers could then directly destroy the foetus with the feeling that they could thus exterminate, within the egg itself, a much-detested breed. One is indeed reminded of Marlow’s realization, early on in the novella, that this horror begins perhaps already with ‘the first arrival of the Romans’ who, fascinated by the ‘abominable’, are going to turn England into ‘one of the darkest places of the earth’ (48). Didn’t Roman law inaugurate the political history of exclusion that will find a form of completion in totalitarian regimes? As it was the case for the Roman homo sacer,30 the Tutsis expelled in the ‘nakedness of life’ see the simple fact of living within the bounds of the juridical order uniquely in the possibility of being killed.

More than 100 years after the publication of Heart of Darkness, the bodies of colonial ideology continue to intoxicate the world. And yet, the genocide is not at all the spontaneous product of the atavism of so-called primitive populations supposedly destined, for all eternity, to the brutal savagery of ‘tribal’ wars. The genocide is the poisonous fruit of a politics that has deliberately instrumentalized the ethnic factor, which the West itself constituted. For centuries, the Hutus and the Tutsis shared the same culture, the same language (kinyarwanda) and the same religion. Then, the Belgian colonists, stigmatized by Conrad, under the influence of a more pervasive Western raciology based on physical anthropology – en vogue in all Europe – created and developed what Lacoue-Labarthe would have probably called the myth of the Tutsis, and affirm, on the basis of morphological and biometric data, the genetic and aesthetic superiority of these ‘feudal lords’, Caucasian aristocrats with delicate features, high brows, straight nose, coming from the north. This thesis, directly inspired from Arthur de Gobineau, advocates the power of the ‘unique Idea’.31 Then, via theology and philosophy, via a theologico-political totalitarianism, via what Philippe in his career-long struggle against totalitarian horrors eventually called ‘national-aestheticism’, this blind belief in the idea will slowly model and fashion the mentality of a people in a plastic, typographic way and introduce, as Philippe also puts it, ‘quite simply the Terror’.32

Such a process of ‘racialization’ of every sort of category would open up the racist rut in which the most extremist Hutus and Tutsis will quickly founder. There are no reasons to doubt this: it is colonialism, itself founded on racist ideology, that is at the origin of the constitution of two separate communities of fear, communities whose antagonism became explosive in 1994. The Whites have, indeed, ‘spoiled the hearts of the Hutus’. And this also – along with the work of death that has been its consequence – belongs to the ‘horror of the West’. The Western will to export its own practices of ethnic cleansing to those very borders of the Congo that fascinated Conrad contributed to the enactment of the most murderous conflict that the planet has known since World War II.

We can, of course, congratulate ourselves that, in matters of international justice, the West has continued, like a guiding light towards progress, to extend what is also part of its project. The designation of genocide has finally been adopted by the United Nations, and these crimes and atrocities have not remained unpunished. And yet, many of the ancient killers have already returned to their own quarters. Moreover, the Rwanda of Kagamé that is now part of the Commonwealth carried on as if nothing had happened: it was reintegrated into globalization, into planetary forms of ‘development’, with a growth rate, as we still say today, previously unmatched. We are left to wonder, though, if the truth that has so often been buried does not run the risk of resurfacing, one day or the other, under the form of an explosion?

Over the past years, the judiciary enclosure of Arusha, the fortress of the ICTR, has become the anonymous and distant place where what Philippe calls the loud ‘echo’ of the ‘savagery’ (116) is allowed to resonate. Protected behind armoured windows, cut off from the public, armed with recording devices of great technological sophistication, a deterritorialized and disembodied justice seemed to retreat in front of the fear to know, defending itself from the fascination of the Thing by taking refuge, as Philippe had already anticipated, in technological manipulation. We also think of the way Conrad’s tragic hero accomplishes, for Philippe, the ‘entire destiny of the West’ (113). We think of the seductive magic of his voice, of his eloquence, of his universal genius, of his sanguinary despotism, of his voracity, of his colonial royalty. These are indeed supplements or inversed images of the ‘barren darkness of his heart’ (HD 147) whose void and hollowness generate a vertiginous ‘emotion of thought’. We also think of the horror to which, at the end, in an Africa that is destroyed, Kurtz finally succumbs, both sanctified and accursed.

‘You will never be able to see the source of a genocide; it is hidden too deep under malice, under the accumulation of lack of misunderstandings. . . We have been educated to absolute obedience, to hatred, they crammed our heads with formulas, we are an unfortunate generation’.33 The lucidity of this president of the extremist militia, accused of premeditated crimes against humanity and condemned to death, is no doubt disillusioned. But if it plunges us into the heart of darkness, by the same token it also enables us to see the obscure origins of this nasty brushwood, this evil forest and, thus, to understand that all this could, indeed, have been avoided. . . This is, in any case, the least desperate of Philippe’s ‘lessons of darkness’. And this lesson must be affirmed even though everything leads us to think, to use Philippe’s expressions one last time, that no work will ever pacify the ‘lament’ of the work of ‘mourning’; no work will ever suspend the curse that ‘the West’ has exported to the entire world. Henceforth, these monstrous atrocities, both unspeakable and inconceivable, will stare back at us. The black heads on the stakes, in front of Kurtz’s ritual abode, with their closed, hollowed out eyes, stand as peremptory signs against future horrors to come. At the same time, at the present moment, the genocidal absolute is already there for all of us to face. And what is the point of thinking – if we do not think through this Thing?

Trans. Nidesh Lawtoo34

For more than two months, repeatedly during the week, I had to live up to Nidesh Lawtoo’s demanding expectations. And that is how, in these back and forth exchanges, the text came to be progressively rewritten à deux mains and the author and friend has become my translator. I would like to express my gratitude to him.

1 François Warin, ‘Coeur des ténèbres’, Lignes 22 (2007): 143–8. This piece, on which the first part of what follows is based, has been substantially revised and extended in order to fit the present volume [editor’s note].

2 Despite their linguistic differences, Dagara people are close to Lobi people and live in Western Burkina Faso.

3 I lived in Africa for 11 years, where I taught philosophy at the ENSup of Bamako first, and then at the University of Ouagadougou. I have often been in the field, particularly in Dogon, Dagara and Lobi regions, whose peoples I introduced to Philippe and Claire. For my recent take on postcolonial issues related to Lacoue-Labarthe’s concerns, see ‘La haine de l’Occident et les paradoxes du postcolonialisme’. EspacesTemps.net, 22 June 2009. http://www.espacestemps.net/document7783.html, accessed 1 September 2011.

4 Friedrich Hölderlin, Remarque sur Œdipe et Antigone, trans. François Fédier (Paris: 10/18, 1965). A few years later, Lacoue-Labarthe translated Hölderlin’s translation of Antigone and Oedipus Rex into French [trans. note].

5 Sally Price, Arts primitifs; regards civilisés (Paris: énsb-a, 1995). In William Rubin, ed., Le primitivisme dans l’art du 20e siècle (Paris: Flammarion, 1987), one can find references to Conrad’s tale (96). See also François Warin, La passion de l’origine: Essai sur la généalogie des arts premiers (Paris: Ellipses, 2006) and ‘Le primitivisme en question(s)’, L’ homme 201 (2012): 165–71.

6 Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Ecrits sur l’art (Genève: Les presses du réel, 2009), 197.

7 Michel Leiris, L’Afrique fantôme, in Miroir de l’Afrique (Paris: Gallimard, 1995), 91–868.

8 Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, ‘La philosophie fantôme’, Lignes 22 (2007): 205–14.

9 Quoted in Michel Beaujour, Terreur et rhétorique: Breton, Bataille, Leiris, Paulhan, Barthes & Cie (Paris: J.-M. Place, 1999), 121.

10 Lacoue-Labarthe, ‘La philosophie fantôme’, 214.

11 René Char, Œuvres complètes (Paris: Gallimard, 1983), 216, n169.

12 Leiris, L’Afrique fantôme, 190–1.

13 Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe. ‘L’Afrique, “. . . cette espèce d’immense nuit. . .,”’, L’Animal: Litératures, Arts & Philosophie 19–20 (2008): 115–16.

14 Proëme de Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, DVD, dirs. Christine Baudillon and François Lagarde (Montpellier: Hors Œil édition, 2006). Reprinted in L’Animal, 115–16, 116.

15 André Vila, an archaeologist at the CNRS and member of the société des explorateurs français, passed away this year. These pictures are reproduced with the kind permission of the photographer’s wife.

16 Not unlike the African mistress in Heart of Darkness, 146 [editor’s note].

17 See the catalogue dedicated to the exhibition of the Château du Grand Jardin: BrunoFrey and François Warin, Lobi, Exhibition Catalogue (Joinville: 2007).

18 Georges Bataille, ‘Post-Scriptum au Supplice’, in L’expérience intérieure (Paris: Gallimard, 1954), 117–81.

19 D’Arusha à Arusha, film, dir Christophe Gargot (Atopic production, 2008).

20 See Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘Tu aimais les Leçons de Ténèbres’, Lignes 22 (2007): 11–15.

21 Jean Hatzfeld, Dans le nu de la vie (Paris: Seuil, 2002); Une saison de machettes (Paris: Seuil, 2005); La stratégie des antilopes (Paris: Seuil, 2008).

22 Georges Bataille, ‘La conjuration sacrée’, in Œuvres complètes, vol. 1 (Paris: Gallimard, 1970), 442–6.

23 Testimony of Faustin Twagiramungu, a figure of the democratic Rwandan opposition, in Christophe Gargot, D’Arusha à Arusha. On the question of the Rwandan genocide, I have benefited from the following works: Amselle, Jean-Loup, and Elikia M’Bokolo, eds. Au coeur de l’ethnie: Ethnies, tribalisme et État en Afrique (Paris: La Découverte, 1985); Ba, Medhi. Rwanda, un génocide français (Paris: L’esprit frappeur, 1997). Chrétien, Jean Pierre, Le défi de l’ethnisme: Rwanda et Burundi, 1990–6 (Paris: Karthala, 1997); Franche, Dominique. Généalogie du génocide rwandais. Bruxelles: Tribord, 2004.

24 Martin Heidegger, Lettre sur l’humanisme, trans. Roger Munier (Paris: Éditions Montaigne, 1957), 157.

25 Isaiah, 24:18.

26 Hatzfeld, Une saison de machettes, 116–17.

27 See Ernst Jünger, ‘Total Mobilization’, trans. Joel Golb and Richard Wolin, in The Heidegger Controversy: A Critical Reader, ed. Richard Wolin (London: The MIT Press, 1993).

28 Hatzfeld, Unesaison de machettes, 61–2. André Guichaoua, Rwanda, de la guerre au génocide: Les politiques criminelles au Rwanda (1990–4) (Paris: La Découverte, 2010).

29 Hatzfeld, Dans le nu de la vie, 51.

30 Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 1998.

31 Lacoue-Labarthe, ‘La philosophie fantôme’, 209. See also Hannah Arendt, Le système totalitaire, trans. Jean-Louis Bourget, Robert Davreu and Patrick Lévy (Paris: Seuil, 2005).

32 Lacoue-Labarthe, ‘La philosophie fantôme’, 209.

33 Hatzfeld, Une saison de machettes, 195.

34 I wish to express my gratitude to Hannes Opelz for discussing the translation and for his careful advice, as well as to Camille Marshall for final stylistic suggestions [trans. note].