Prologue

The age of hieroglyphs is not dead. Pictograms direct road traffic, point us to exits and toilets, and invigorate trademarks, logos, and the computer world. A little experience also makes familiar the emblems of nationhood (flags, anthems), professions (uniforms, insignia), religion (crucifix, star of David), other perils (skull and crossbones), sex (reader’s choice). With more knowledge, we can identify personifications of such abstractions as Justice (with her sword and scales), War (Mars), Love (Venus, Cupid), the Seven Liberal Arts, and the Five Senses. In early modern Europe, educated people who spent most of their quality time with ancient authors could read the iconography of the old myths and Bible stories as plain text. They understood the power of icons. Francis Bacon: “Emblem reduceth conceits intellectual to images sensible, which strike the memory more.”1 Emblems, images, symbols, and hieroglyphs speak directly; they do without Bacon’s “idols of the marketplace,” words made ambiguous through everyday use.2 The unmediated representation of Bacon’s inamorata, Lady Philosophy, was grave of expression, disdainful of ornament, outwardly poor, and, we suppose, internally rich.3

The hieroglyph whose elucidation frames this book hides in a painting made in Oxford in 1643–4. The painting presents the unhappy young heir of Corfe Castle, John Bankes, and his concerned tutor, Dr Maurice Williams (see Figure 1). Neither seems to have left in print more than a Latin poem or two to mark his passage through this life, and the portraitist, the once-famous Francis Cleyn, is now almost as forgotten as his sitters. The hieroglyph is the open book lying on the table together with a telescope and globe (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Francis Cleyn, “Our Painting” (1643/4): Dr Maurice Williams (standing, with hand on globe) and John Bankes.

Figure 2 Our puzzle: detail of Figure 1.

Although, as depicted, the book lacks author and title, people who had seen the illustration on its title page would have identified it immediately as the last great example of the learning, spirit, and style of Renaissance Italy. It is Galileo’s Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi (1632), Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, the famous defense of Copernican cosmology that earned its author the attention of the Inquisition, perpetual detention in his small villa outside Florence, and the reputation of a martyr to freedom of expression. The painting is perhaps the earliest iconographical reference to Galileo outside of portraiture. Whatever the reasons for its presence in Cleyn’s work, Bankes and his friends saw more in it than the modern viewer who interpreted the “stack of books” at which young Bankes points his compass as representing “the educational value of travel.”4

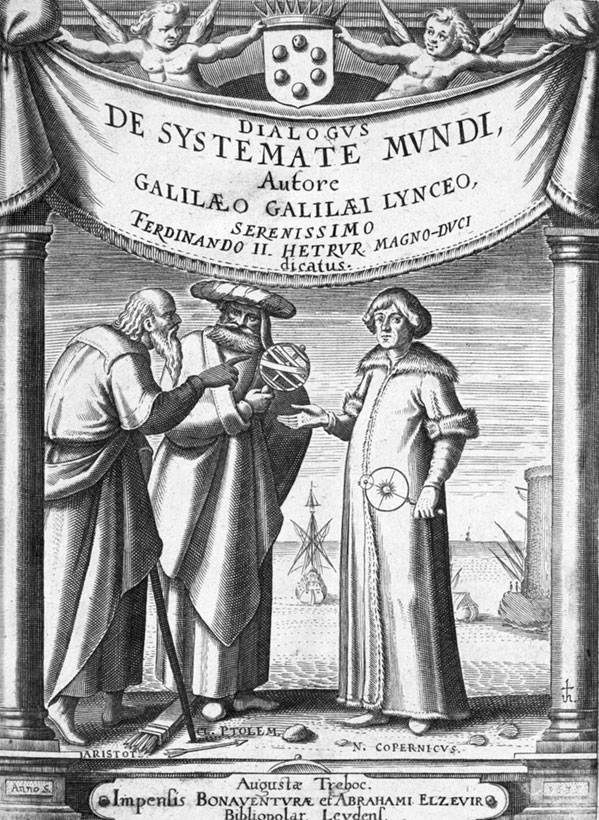

Although Cleyn’s image is impressionistic, it is clear enough to show that he did not draw it from the Italian original, become rare by execution of Pope Urban VIII’s order to destroy all procurable copies, but from the Latin translation made by a German Protestant, Matthias Bernegger, and printed in 1635 and again in 1641 by the Elzeviers of Leyden. The frontispiece to the Italian edition shows (from the left) Aristotle and Ptolemy, the chief ancient authorities in physics and astronomy, arguing with Copernicus (see Figure 3). All three appear elderly and bearded, Copernicus looking much as Galileo did late in life, and they are modeled softly, as if their argument had no rough edges, and flexibly, as if they might be capable of changing their opinions. The characters in the redrawn frontispiece of the Latin edition (see Figure 4) are static, with hard outlines, as if to suggest rigid positions and confrontation. Aristotle and Ptolemy retain their beards and old-fashioned dress, whereas Copernicus has been rejuvenated, appearing as he drew himself, youthful and clean-shaven. Evidently, Cleyn copied from the Protestant edition.

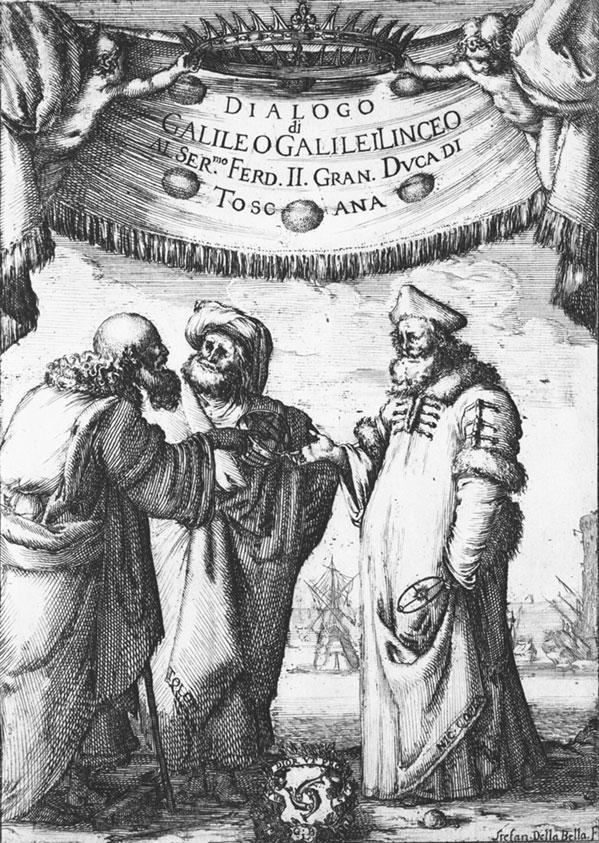

Figure 3 Stefano della Bella, frontispiece to Galileo’s Dialogo (1632).

Figure 4 Jacob van der Heyden, frontispiece to Systema cosmicum/Dialogus de systemate mundi (1635), the Latin translation of the Dialogo. The frontispiece to the reprint of 1641 is the same, to Cleyn’s approximation.

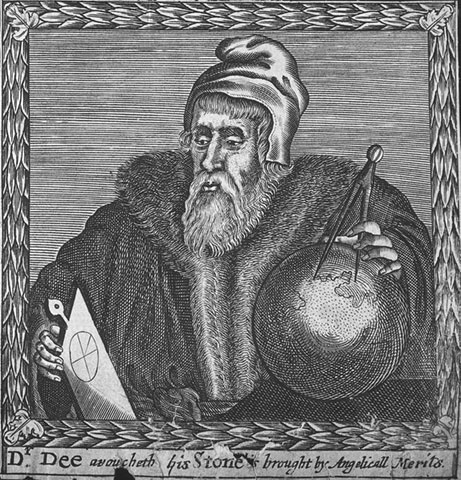

Before moving to England in 1625, Cleyn had studied and worked in Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark. A genial jack of all graphic trades (see Figure 5), he had the skills for the important position of chief artistic designer of a tapestry works encouraged, and eventually acquired, by King Charles I. The works were installed at Mortlake, near Richmond, upriver from London, on the premises of the former library and laboratory of the great Elizabethan magus and astrologer John Dee. Dee’s ghost will haunt these pages now and again, as, apparently, it did Cleyn (see Figure 6). Maurice Williams served briefly as a physician to Queen Henrietta Maria after the judicial murder of his patient and patron, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, once the most powerful of King Charles’s ministers. John Bankes was the son of Sir John Bankes, a one-time opposition parliamentarian who joined Charles’s government, first as Attorney General and then as Chief Justice of Common Pleas. Sir John no doubt commissioned the painting and had his own reasons for improving it with the Galilean hieroglyph. Cleyn’s double portrait thus has impeccable royalist connections. The painter, the doctor, and the lawyer all owed their positions and loyalty to the king and were present with him in Oxford during the Civil War.

Figure 5 Unknown artist, Francis Cleyn.

Figure 6 Francis Cleyn, John Dee, from the frontispiece to Casaubon, Relation (1659).

The painting has many more ties to Oxford. Williams and the Bankses, father and son, and many of the secondary actors in our story attended the university. And Galileo often was virtually present there. We catch an early glimpse of him at a celebration of the university library, founded by Thomas Bodley, who died three years after Galileo announced his discovery of mountains on the moon. The celebrant yanked in the discoverer with a far-fetched conceit: “I remember, O Galileo, your saying that a certain mountain protrudes above the surface of the moon…[Y]ou are deceived; for the shadow you observed is that of a high library, a Bodleian work that soon will give other marks [of eminence].”5 Among the marks are several copies of the first editions of Galileo’s Dialogue preserved in its collections.

Galileo delivered his opening set of discoveries in 1610 in a little book entitled Sidereus nuncius, which signifies both a message from the stars and their messenger. The messenger did not then draw out the bearing of his message on the great Copernican question, whether the earth spins (creating night and day) and revolves about the sun (creating the seasons). He believed that he had evidence to decide for Copernicus; but he did not present it in full in print until 1632, when, with the permission of the censors, he published his Dialogue. The book belongs to an extinct genre. It presents new knowledge through a compelling mix of farce and philosophy, of wild exaggeration and exact mathematics, of goring of sacred cows and fishing of red herrings. Pope Urban regarded it as one of the most pernicious books ever written. Its gravest fault for him was its insinuation that the Copernican system must be correct and all others false. Urban might have been content if Galileo had declared the Copernican the best of the bunch and left them all as hypotheses. According to the pope’s philosophy of science, we cannot do better: God in his capricious Omnipotence can always bring about the phenomena in a myriad of different ways inconceivable by us. Galileo’s insistence on the Copernican worldview thus challenged an epistemology endorsed by the pope that made God’s will, however capricious, paramount. Voluntarism, to give this epistemology its name, had the merit for literal believers of safeguarding interpretation of Scripture against all challenges based solely on natural knowledge.6

Voluntarism was but one of the victims of the two ghosts and unique booby whose conversations make up the Dialogue. The ghosts are Filippo Salviati and Gianfrancesco Sagredo, formerly and respectively a Florentine patron, who acts as Galileo’s spokesman, and a Venetian carousing companion, who approves and supplements Salviati’s teachings. The booby is Simplicio, the only gentleman among them, a philosopher who has trouble thinking for himself. Their talks take place over four days in Sagredo’s palace in Venice. During the first three, Salviati destroys all Simplicio’s arguments for placing the earth at rest in the center of the universe; on the last day he tries to show that he and his friends and Sagredo’s palace reside on a spinning planet racing around the sun.

The magic and mystification of the Dialogue begin with the frontispiece that figures in Cleyn’s painting. The title, which Cleyn omitted, announces a confrontation between the two chief world systems, the Ptolemaic and the Copernican. The artist, Stefano della Bella, illustrated the confrontation, and hinted at Galileo’s solution to it, by placing the figure of Copernicus alone on the right, separated by a space from those of Aristotle and Ptolemy on the left (see Figure 3). The grouping suggests the need for a philosopher to supply the physics needed to put and keep the planets in orbit around the sun. Although Galileo may have hoped to supply the great desideratum of an exact physical astronomy, he had to leave the position blank. The blank gave Salviati a decisive advantage: he could attack traditional physics without having to defend a new one against Simplicio. The depiction embodied another dissimulation: in the frontispiece, two ancients appear against one modern; in the book, two Copernicans joust with one Aristotelian.

The Dialogue thus has features of a teaching manual that proceeds by exchanges among a schoolmaster, a fast pupil, and a dunce. There is also something of the commedia dell’arte (at which Galileo once tried his hand) in the clever outwitting of plodding authority. Again, the Dialogue resembles a play in its noble setting and fast conversation, and in its dissembling prologue, which gives as the author’s motive in writing a desire to show that the Roman censors who banned Copernicus’ book on theological grounds knew as much astronomy as the Protestants who snickered at them.

Deciphering Cleyn’s painting has required juxtaposing material not usually mixed, such as attitudes toward things Italian in England; Stuart court culture; gentlemanly knowledge of astronomy and astrology; information about the protagonists Sir John Bankes, Maurice Williams, and Francis Cleyn; and theatrical inventions. The frontispiece of the Dialogue connects with the stage by displaying the author’s name and the book’s title and dedicatee on a raised curtain; Galileo frequently refers to the book as a play, and Salviati as a character in masquerade; and much of the Dialogue is theater in the Renaissance sense of theatrum mundi, which might refer both to the physical world and to the world stage on which we act our petty parts.7

Italians, especially Florentines, led the way in theater science, which came to England via Inigo Jones’s elaborate staging of court masques. These entertainments have a strong claim on our attention, not only for their Italian and court connections, but also for their richness in astronomical and astrological wordplay. People who possessed the requisite star lore, which could be absorbed from poems, paintings, elementary textbooks, and the ubiquitous almanac, would be able to decode several messages from Cleyn’s painting.

According to the great authority Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, every competent portraitist could distinguish and represent eleven passions of the mind. Cleyn’s canvas conveys one of them to perfection: melancholy.8 Melancholia was a frequent academic complaint, occasioned, as everyone knew, by an excess of black bile. Depending on the nature and degree of the imbalance, the sufferer could be a genius or a madman. Our exploration must thus penetrate the delights and miseries of the atrabilious, especially love melancholy as experienced at Oxford when John Bankes studied there, and that ubiquitous and pernicious black-bile disease baptized by its anatomist, Robert Burton, as “religious melancholy.”

Concern with religion, whether as a guide to eternal life or mundane politics, or, to the nonconformist, as an endemic background terror easily manipulated into foreground panic, was never further from people’s minds than a church was from eyeshot. This was never far in England. First among the features of the country most striking to a Venetian ambassador reporting in 1613 was the “quantity of most beautiful churches so numerous as to pass belief.”9 Very numerous, too, were the shades of belief taught in these places, and very hard and belligerent the teachings of their more atrabilious preachers.

Catholics appear frequently in these pages despite arbitrary persecution and modest numbers, amounting, probably, to around 5 percent of the population of England. Unwelcome at home because allegedly (and sometimes truly) more obedient to the pope than to the king, they could travel easily in Italy and report back what they found. Several Scots and Englishmen who studied in Venice or Florence or Rome wrote about Galileo’s discoveries and disputes as they happened. Catholics could also act conveniently as middlemen in the increasingly sophisticated appreciation of art and connoisseurship in England, which brought modern Italian painting, and painters like Cleyn with Italian training, to the Stuart courts.

The largest frame for situating our inquiry is the political, especially as expressed in relations between the kings and their parliaments and in the mismatch between their ambitions and income. Sir John Bankes experienced all the vicissitudes of Charles’s reign as a parliamentarian and then as a government official, and occasionally was able to help steer events. Williams understood the pathways of patronage through his connections with Strafford and the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, and experienced at first hand the religious politics of the reign at the Catholic–Protestant front in Ireland. Another front, in Venice, which opened early in the English reign of Charles’s father, King James I, familiarized many Englishmen with Venetian republicanism, with the possibility of a stable polity that tolerated religious dissent, with revolutionary thinkers such as Galileo and his friends, and with the allure of religious art and honest courtesans. Both Cleyn and Williams spent several years in Italy, and young John was to travel there, whence he returned, calling himself Giovanni Bankes, several years after Cleyn had painted his portrait.

I stumbled across Cleyn’s painting in 2010 during a casual visit to Kingston Lacy, the Bankes’s former estate in Dorset now owned by the National Trust. I have not been able to unriddle its Galilean hieroglyph in the manner of Sherlock Holmes, who worked by excluding everything not immediately relevant to his investigation. He had not heard of Copernicus before Dr Watson told him that the earth travels and he then did his best to forget it. I have been obliged to copy the melancholic Burton, raking over all sorts of material, some perhaps not strictly pertinent to my inquiry, but not known to me not to be. There is no end to the potentially relevant.

Doubt not but in the end you will say with [Burton], that to anatomize this [painting] aright…is as great a task as to reconcile those chronological errors in the Assyrian monarchy [and] find out the quadrature of the circle.…as great a trouble as to perfect the motion of Mars and Mercury, which so crucifies our astronomers, or to rectify the Gregorian calendar.10

I have set out what I think relevant to the painting in a manner that should satisfy the strictest Trinitarian. The first three chapters sketch the background: Rome with its resurgent papacy and Venice with Galileo and his subversive friends; conflicts among the main Christian sects and between prerogatives and privileges in the mixed and muddy Stuart government; and the eccentricities and random shrewdness of James, the culture and self-deception of Charles, and the struggles of both against Puritans and parliaments. As far as the documents allow, these wide matters are presented through the particular experiences of Sir John Bankes. Chapters 4–6 take up cultural matters pertinent to Cleyn’s picture: literature, theater, art, and popular astrology; cosmology and elevated astrology; melancholy and medicine. The last three chapters are devoted to the painter; the situation in wartime Oxford, where Sir John, Sir Maurice, young John, Dr Williams, and Francis Cleyn came together to make our painting; and a Galilean dialogue between Cleyn and his sitters exploring the painting’s meaning.

In treating these many themes, I have had Cleyn the designer of tapestry in mind. Threads from the histories of art, literature, science, medicine, politics, law, and religion come in and out, in a way that his contemporaries might have experienced them, which is not how modern historians have divided them. None is teased out to an extent that would have challenged the learning of an ordinary Jacobean or Caroline gentleman. This learning included cosmology, not as mathematics, but, as we learn from Henry Peacham’s Complete Gentleman (1622), as a “sweet and pleasant study,” more recreation than labor, “besides being quickly, and with much ease attained to.”11

Galileo’s image is multivalent. We see its flexibility in its contrasting employment by the anti-royalist John Milton, in his well-known argument for an almost free press, Areopagitica (1644), which appeared within a year of our picture, and by the royalist Sir John Bankes, in commissioning a portrait of his melancholy son. A postscript outlines the exploitation of Galileo’s image by reactionary as well as by progressive forces since Cleyn began the process four centuries ago.