4

Cultural Threads

King James’s Handful

Jacobean Cosmology

In October 1589, a violent storm forced the ship carrying James’s 15-year-old bride Anna, whom he had married by proxy, to seek refuge on the Norwegian coast. Her voyage began with a misfired salute to the Danish–Scottish alliance that blew up the guns and the gunners. Despite the omen, against all advice, completely out of character, and although he preferred no wife to any, James set forth upon the stormy deep to get his queen and beget an heir; “as to my awne nature, God is my witness, I could have abstaint langair nor the weill being of my patrie could have permitted.” The ardent wooer had courage for only one winter crossing of the North Sea.1 He spent his long honeymoon in Denmark talking Latin with the great astronomer Tycho Brahe and other learned men. Brahe worked on a small island, Hven, given him by Anna’s father, where he had built the largest observatory in Europe. With the help of students and visitors he sometimes marooned there, Tycho measured the positions of the stars and planets more accurately than anyone had done before.

James visited Tycho’s island for seven hours just before the vernal equinox of 1590. He and his host inspected instruments, wrote epigrams, and talked about world systems.2 James prided himself on his first-hand knowledge of Tycho’s work. “We have seen it and heard about it, with our own eyes and ears, in your castle dedicated to Urania; and in wide-ranging learned and interesting conversation with you we have been so elevated that it is hard to decide if our pleasure or our admiration is the greater.”3 Although James advised his sons Henry and Charles against acquiring knowledge for its own sake, “nakedly…like those vaine Astrologians, that studie night and day on the course of the starres, onely that they may, for satisfying their curiosity, know their course,” he had allowed himself to learn enough of this “most necessary and commendable” science to appreciate the import of astronomical discoveries.4

Very probably James had learned his astronomy grudgingly from a long Latin poem by his tutor, George Buchanan, an adventuresome humanist who had spent his young manhood on the Continent studying and teaching as a Catholic before returning to Scotland and the Reformed Church. James heartily hated him for his stern discipline and perverse advocacy of the right of Scots to depose a tyrannical king.5 Among Buchanan’s unwelcome teachings was respect for the Venetian constitution; as he saw it, a king should be little more than a doge, an executive of a constitutional government, an ordinary human being subject to the law. He counseled James presciently but ineffectually to despise flattery, favorites, and incompetents. Buchanan developed these liberal ideas in a book on Scottish history, De jure regni apud scotos (1579), that made him additionally odious to his tutee; for Buchanan judged that Scottish law and customs justified the forced abdication of Mary Queen of Scots.6 The book became notorious: the Scottish Parliament banned it (1583); the Long Parliament took it as a fundamental text; the University of Oxford burnt it (1683); American revolutionaries consulted it. That suave defender of James’s mother Mary, George Conn, likewise dismissed Buchanan’s history (“infamous lies”) and condemned its author (“that impostor,” “that malicious dissembler”).7 But in James’s time, and in Denmark, Buchanan was the prince of Scottish scholars. A portrait of him hung in Uraniborg.8

Tycho’s successor Kepler supposed that the cosmic harmony he heard among the stars might be brought to earth by his fellow student King James. Did not James’s skill in damping discord in his ill-assorted kingdoms, and in nudging most English Protestants toward the same hymnbook, betoken a healthy polyphony in church and state, conducted by a ruler in step with the law? This was the way to manage human affairs as well as celestial motions! Midway through his wild exposé of world harmony, Harmonices mundi (1619), which he dedicated to James, Kepler expressed the essence of the best possible polity by an arithmetic–geometric proportion.9 Knowing how earth related to heaven, human government to divine, and scepter to telescope, the Scottish Solomon would know how to use the perspective Kepler offered him. “O Telescope…Is not he who holds you in his right hand made King and Lord of the works of God?”10

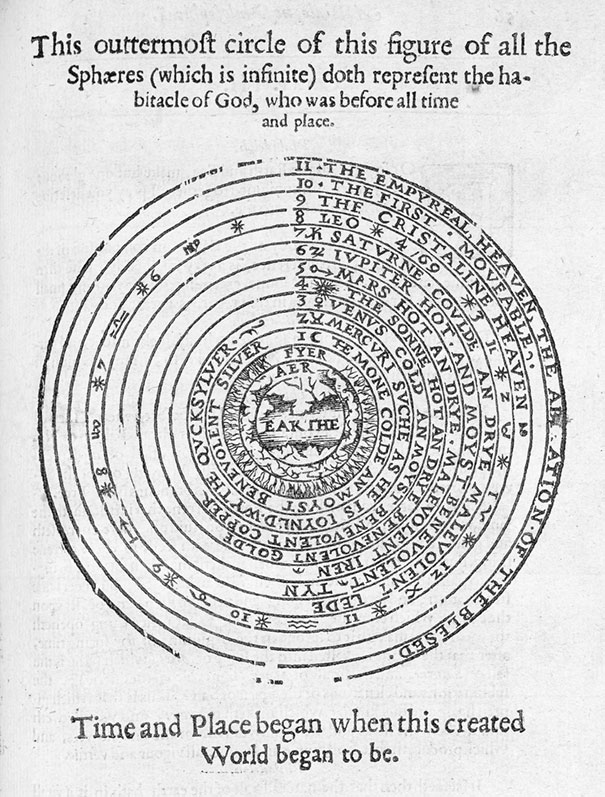

In England, too, a bold thinker linked James’s mastery of astronomy to the concord of Christianity. He was Thomas Tymme, a preacher devoted to alchemy.11 In a dialogue published in 1612, Tymme made James the arbiter between a sharp docile student, Philadelph, and a dull preachy teacher, Theophrast.12 Theophrast defends the traditional cosmology (Figure 17). Would it not be more economical, Philadelph asks, to spin the earth than the heavens, and more reasonable to place the earth in orbit than the planets on epicycles? Theophrast offers the crushing rejoinder: “[I]t seemeth you will preferre novelty before Antiquity.” Such hubris! To join the crowd of arrogant fools who have “laboured to draw out of the shallow Fordes of their owne braine, the deepe and unsearchable misteries of god”! Aristotle had died from this intoxication. Unable to explain the tides, he had leapt into the sea crying lengthily and cleverly, “Quoniam Aristoteles mare capere non possit, capeat Aristotelem mare,” a proper ending, says Tymme, for a man who “asketh to be wise without God and his word.”13

Figure 17 The universe according to Thomas Tymme, A Dialogue Philosophical (1612), 55.

Philadelph observes that his teacher has not answered Copernicus’s arguments. Theophrast replies with Joshua’s stopping of the sun and other decisive texts and, though unnecessarily, adds that he has seen a convincing material model of a geocentric universe. This was a perpetual astronomical clock with an attachment that simulated the diurnal motion of the tides. Its inventor, James’s Dutch engineer Cornelius Drebbel, claimed that the motion was perpetual. Philadelph rightly doubts the pertinence and perpetuity of the model but surrenders instantly on learning that King James certified it. Tymme said nothing about Galileo’s discoveries.14 Soon, however, his readers would be able to reinforce Philadelph’s doubts by viewing Jupiter’s moons through glasses made in England by Drebbel.15

One of Galileo’s former students saw a duplicate of Drebbel’s ingenious machine made for the emperor and described its tidal simulator to his master. It consisted of an air-filled metal sphere fixed to a vertical hollow ring half filled with water (Figure 18). The fixing (the vertical axis) conceals a hollow pipette and a partition that divides the ring into two branches. A small hole in the sphere’s equator allows its interior and, via the pipette, the left-hand branch, to communicate with the atmosphere. When the external temperature rises, the pressure in the globe and branch increases and the water moves anticlockwise; cooling reverses the motion; thus two tides a day.16 By 1616, when Galileo began to circulate his tidal theory, Drebbel’s natural magic had spread beyond the cabinets of kings and emperors (Figure 19). Was it in response to it that Galileo claimed to have a machine (never exhibited!) that mimicked tidal motion in a semi-circular canal? The device created for the amazement of King James might well have reinforced Galileo’s commitment to the theory that capped the Copernican argument of the Dialogue.17

Figure 18 Cornelius Drebbel’s perpetual motion machine (c.1610); detail of Figure 19.

Figure 19 Jan Brueghel the Elder and Hieronymous Franken II, The Archdukes Albert and Isabella Visiting a Collector’s Cabinet. The yellow sphere to the rear, left, is Drebbel’s perpetual motion machine.

James picked up more than astronomy and Anna during his stay in Denmark. He adopted the theory of witchcraft he developed in his demented Daemonologie (1597), which accepts that witches can cure or cause disease, induce love or hate, conjure sprites, ruin digestion, sail in sieves, and “raise stormes and tempests in the aire, either upon Sea or land.”18 This last power he had experienced himself: for it was quite true, as rumor on both sides of the North Sea reported, that witches had called up the storm that detained Anna. Some crones encouraged by torture explained how to stir up a tempest by tying human body parts to a cat before throwing it into the sea; none of them, however, knew how to turn off a breeze. One terrified woman terrified the king by reporting the words he had whispered privately to Anna on their first night together; “whereat the Kinges Majesty wondered greatlye, and swore by the living God that he beleeved that all the Divels in hell could not have discovered the same: acknowledging her woords to be most true, and therefore gave the more credit to the rest.” Why did the devil desire his followers to drown the royal couple? The witches’ answer, that the devil feared James of all men, proves that the Evil One was a Papist; “the union of a Protestant princess with a Protestant prince…being…an event which struck the whole kingdom of darkness with alarm.”19

James had his Daemonologie reissued the year he became King of England. His new subjects needed to know that witchcraft abounded among them.

For the great wickednes of the people on the one part, procures this horrible defection, whereby God justly punishes sinne, by a greater iniquity: And on the other part, the consummation of the world, and our deliverance drawing neare, makes Sathan to rage the more in his instruments, knowing his kingdom to be so neare an end.

The wicked people heard, and presented the king with a play, Macbeth, in which witches sail in sieves, raise the winds, and predict the future with dreadful accuracy. Soon some fraudulent accusations that James himself exposed caused him to doubt the Satanic pact.20 Later he “laughed consumedly and made great fun of the Catholics saying they put their trust in the oaths and depositions of the demon and in the things which idle persons and witches say they see in their diabolical games.”21

“Learning,” opined the playwright William Davenant, “is not knowledge, but a continu’d Sayling by fantastic and uncertain winds towards it.”22 James accepted continental learning about witches until favorable winds drove him to a better position. It would have taken a hurricane to move the very learned Archbishop Ussher. Knowing from revelation that the devil had been let loose around the year 1000, Ussher was not surprised by a message delivered via a fish in Cambridge market in 1626. The fishy message was a copy of Richard Tracy’s A Preparation to the Cross (1540), which warned about the scourges God visits upon us for indulging “luste of the fleshe, concupiscence of the eyes, and pryde of life.” Ussher: “the Accident is not likely to be lightly passed over, which (I fear me) bringeth too true a Prophesy of the State to come.” To reinforce the message, God, still in a maritime mood, sent a great waterspout up the Thames right into the garden gate of Buckingham’s riverside mansion. Ussher again: “[L]et the Lord prepare us for the day of our visitation.”23 Ussher’s alertness to such announcements may serve as a salutary reminder that in early Stuart times, as no doubt now, rational discourse and great learning can paper over a world of beliefs incompatible with them. It is as unfair to smile at Ussher’s sensitivity to omens as to cavil at his error of thirteen billion years in dating Creation to 23 October 4004 bce, towards 6:00 in the evening.

Missed Opportunities

James might have been a mighty patron of the arts and sciences had he been rich and decisive enough to support the meritorious projects submitted to him that later British monarchs saw fit to patronize. Three of these proposals if implemented would have given him a unique, and uniquely balanced, portfolio of initiatives in history, literature, and natural science.

When James came to England, a small group of antiquaries centered on William Camden, a senior official in the College of Heralds, met regularly to discuss old charters, inscriptions, monuments, and coins. Among those who agreed with him that the study of antiquity “hath a certaine resemblance with eternity” were Arundel and Andrewes. Other members of the group were Lord John Lumley, a relation of Arundel, famous for his library; Robert Cotton, a former student of Camden, also famous for his library, in which much of Dee was preserved; John Spelman, a lawyer with a passion for Saxon studies; James Ussher, who often left his posts in Ireland to collect books in England; and John Selden.24

In 1603, Camden’s group petitioned Elizabeth for a charter to establish an Academy for the Study of History and Antiquity and a royal library for the collection and preservation of old books and manuscripts. She died before she could act on the proposal. James signaled that he would like Camden’s group to disappear. Its concern with the relative antiquity of kings and parliaments could raise difficulties for a monarch who held prerogatives by divine right. Although the group stopped meeting around 1608, the legal historians among its members found ways to continue to alarm the government.25 Their arsenals were their libraries stocked with useful documents inaccessible in the Tower or the Exchequer, or unknown there because lost or crumbling.

The antiquarian lawyers did not confuse knowledge of the “desents, genealogees, and petygrees of noble men…& such like stuffe” with true history. The words just quoted come from a primer on the writing of history by the Italian philosopher Francesco Patrizzi, as rendered by Thomas Blundeville, who also taught Englishmen mathematics and navigation. Blundeville–Patrizzi specify that true history seeks motives in the backgrounds, parentage, education, ambitions, and habits of the actors, and “tell[s] things as they were done without either augmenting or diminishing them, or swarving one iote from the truth.”26 The most famous of historian–lawyers, Francis Bacon, likewise advised his readers “diligently to examine, freely and faithfully to report, and by the light of words to place as it were before the eyes, the revolutions of time, the characters of persons, the fluctuations of counsels, the courses and currents of actions, the bottoms of pretences, and the secrets of governments.”27

A good indicator of the danger of history is Cotton’s Short View of the Long Life and Rayne of Henry the Third, which circulated in manuscript from 1614 until published in 1627. Almost as compromising in its context as Sarpi’s Trent in papal Rome, Cotton’s Short View exhibits parallels between the corrupt rule of a favorite in England under Henry III and Britain under James, and a more striking anti-parallel: Henry came to his senses, got rid of his favorite and foreign intriguers, cut his expenses, and governed responsibly with the aid of a wise Privy Council.28 Although written against Carr, when published in 1627 it had obvious reference to Buckingham. So did Sejanus: His Fall (1603, 1616), by Ben Jonson, written with the help of Cotton’s books, which details the crimes of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, the favorite of Emperor Tiberius. Its timeliness became clear as Buckingham accumulated power. Cotton’s library continued to supply unwelcome recondite precedents deployed by parliaments. In 1629, King Charles shut it down. He thereby deprived his enemies of, among many other things, two copies of Magna carta and the conjuring apparatus of John Dee.29

Notable users of Cotton’s library included Arundel, Ussher, and Lord William Howard.30 We suppose that the learned and rising John Bankes also belonged to Cotton’s circle, since, like Bankes, Cotton and Cotton’s son held Howard seats in parliament.31 These allegiances by no means precluded occasional cooperation with the Crown. As Attorney General, Heath and then Noy used precedents dug up at their request by Selden, Cotton, and Spelman.32 Selden accepted a commission from the House of Lords to settle with documents the pressing questions whether a peer could take a deer from the king’s forest, whether his privilege of being free from arrest while parliament sat extended to his servants, and whether he could claim benefit of clergy if illiterate. Spelman served on a committee to review legal fees that had grown wildly over time: fees for taking oaths, for burial, and for copying, which in one remarkable case consumed sixty-five skins and £272 more than necessary and in another forty sheets where six would have done. Spelman’s reasonable proposals for reform, based on firm precedents, met with firmer opposition from profiteers and failed to be adopted.33

More successfully, Cotton found a precedent in the reign of Henry IV for parliament’s voting a subsidy before its grievances were redressed; discovered no precedent against the creation and sale of the title of baronet, which for a time brought the crown £30,000 a year; used the relative privacy of his library to open negotiations with Gondomar over the Spanish match; and hunted up, for Buckingham, precedents for ridding the country of obnoxious ambassadors. None of these services kept him out of the Tower in 1629 or reduced his sojourn there.34 Although Bankes supported Cotton and Selden, as usual he managed to avoid compromising himself.35 He did not write books.

The exemplar of the symbiosis between antiquarian research and legal argument was Selden. After training in the Inner Temple, he became a copyist for Cotton’s library and a most effective exploiter of its holdings. He annoyed the Stuarts by demonstrating that laws and assemblies preceded the institution of kingship. In Titles of Honour (1614) he went after the regalia and status of the nobility, including the kings of England, whose crown and scepter, and notions of divine right, he showed were relatively recent inventions. The title “Majesty” came in with Henry VIII, and a “Stuart” was but a thane, a dignity scarcely higher than a baron. Selden reached these conclusions with the help of “that Medium only, which would not at all, or least, deceive by Refractio,”—that is, the perspective (the metaphor of the age) offered in the libraries of Cotton and “my beloved friend that singular Poet Mr Ben Jonson.”36

Selden’s answer to his fellow antiquarian Henry Spelman’s defense of tithes as a divine right of clergy showed what examination through the perspective of document-based history could do. Selden found no evidence of tithing in the early church and no evidence of its establishment in Europe until Charlemagne and in England before Henry III. The claim to dole by divine right was an invention of the popes of the later middle ages. “Experience and Observation” thus wiped out “so much headlong Error, so many ridiculous imposters.”37 The erring establishment did not welcome this enlightenment. The bishops (apart from Selden’s close friend Andrewes) read Selden’s book as a slur on their learning as well as an attack on their revenues. We are not so ignorant, they said, as not to perceive the tendentiousness under the footnotes. “History disputeth not Pro, or Con; concludeth not what should be, or not be…This you have not observed, Master Selden, but made yourself a Party, which no Historian doth.”38 “[The] historical way,” says Bacon, “[is] not wasting time, after the manner of critics, in praise and blame, but simply narrating the facts historically, with but slight intermixture of private judgment.”39 Selden answered the bishops that he had followed the way of Bacon. The facts spoke for themselves, once he had arranged them; to write them down as he had picked them up would have been “too studious [an] Affection of bare and sterile Antiquitie”—that is, worthless. But the bishops prevailed. Selden’s brother in learning, King James, compelled him to retract.

While working on tithes, Selden buried, or rather drowned himself, in that investigation of the law of the sea from which he dredged up the doctrine that water could be owned as well as land. As we know, James did not like the conclusion and, going further than he had with Selden’s history of tithes, prohibited the publication of Mare clausum altogether.40 Fortunately James did not know the extent of Selden’s deviancy. The great lawyer regarded the interpretation of Scripture as guesswork and predestination as unintelligible and challenged resurrection by directing that he be buried under ten feet of soil, a large block of marble, and a pile of bricks.41

Like Cotton, Selden sat in Howard seats in parliament, belonged to Arundel’s academy of Italophile savants, and acted as an independent consultant at the highest level. He supplied Bacon with information for his history of Henry VII, catalogued Arundel’s famous Greek marbles, helped Ussher calculate the eve of creation, and advised King James about the dating of the Nativity and the meaning of the number of the beast.42 Selden admired Sarpi’s writings and practiced a similar historiography. He thus found himself in and out of favor with his sovereigns, who liked Sarpi’s approach when directed at the papal, but not at the Stuart court.43

The researches of the legal historians easily exploded the notion of an ancient perfect balance of church, monarchy, and state. When could that have been? Before the dissolution? But then we were all Catholics and the pope had his finger on the balance. Since the dissolution? But in recent years we have seen Magna carta violated, church property destroyed or perverted, T&P illegally collected. There had never been an idyllic past any more than there had been a Brute, descended from Aeneas, who settled the British Isles. There were plenty of indigenous brutes, however, three kingdoms full of them according to their historiographer Camden. Here astrology came to the aid of history. The fiery trigon Aries, Leo, and Saggitarius in collaboration with Jupiter and Mars “maketh [the British] impatient of servitude, lovers of libertie, martiall and courageous.” This flattering picture improves the description in Camden’s source, Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, which adds that northern people with close familiarity with Aries and Mars, such as Britons and Germans, tend to be fierce, headstrong, and bestial.44 Camden discovered on his own that, when Saturn sits in Capricorn, plague invariably arrives in London, and that a certain eclipse (unspecified, so as to spare worry) is “'fatall to the Towne of Shrewsbury.”45

The second project proposed to James, which frightened him less than the antiquaries’, called for an “Academ Roial” modeled on Florence’s Accademia della Crusca, which had charge of the literary affairs of Tuscany. Its moving spirit was Edmund Mary Bolton, a Catholic gentleman and minor poet whose friends included John Donne, Ben Jonson, and Inigo Jones. In 1617, Bolton approached Buckingham, a kinsman, with a plan of literary renewal that would cost only £200 a year. Buckingham supported it. James had wanted to set up “an academy for bettering the teaching of youth, and for the encouragement of men of art,” but could not spare money from his hunting to do so. In 1622, he turned the project over to Charles. Nothing came of it. Two years later James took up the arts side of his academy in the form Bolton had proposed and went so far as to concern himself with the design of the group’s seal (himself on one side, Solomon on the other), the rights of precedence of its members, and other essential academic matters. Nothing more came of that either.46

Bolton divided the membership of his proposed academy into two classes: drones (consisting of “Tutelaries” like Knights of the Garter and “Auxiliaries” chosen from ordinary peers) and workers (“Essentials,” leisured gentlemen at least 30 years of age). Many of Bolton’s Essentials were Catholics or well disposed towards them: Ben Jonson, George Gage, Endymion Porter (Bolton’s brother-in-law), George Fortescue, Tobie Matthew, Sir Thomas Aylesbury (a mathematician who invented a way to coin money and became master of the Mint), and that knight of miscellaneous learning, Sir Kenelm Digby, “the Pliny of the age for lying.” Other prime candidates were Henry Wotton and three veterans of Camden’s group, Cotton, Selden, and Spelman.47

The academy would serve (so Bolton told James) “for the universal embetterment of your people, for the more advantage of your kingly prerogative, certainly for your Majesty’s greater comfort, and for the everlasting fresher glories of your name among us.” Its duties included policing translations, especially of classical authors often mangled by hacks; drawing up expurgatory indexes of English books; overseeing the composition of a “spare and free authentic” celebratory history of England; and “keep[ing] a constant register of public facts.”48 Had James lived to endorse these activities, he almost certainly would not have paid for them. This much we can infer from the story of Chelsea College, established with royal backing in 1610.

Chelsea’s purpose was to train controversialists to help James confute the “lyes, slanders, heresies, sects, idolatries, and blasphemies” of Pope Paul’s army of seasoned Bellarmines. As its dowry it had enough timber from a royal forest to build an eighth of its fabric. Its first provost, Matthew Sutcliffe, Dean of Exeter, was a satisfactorily paranoid anti-Catholic. But, although Sutcliffe put his own resources into the college and several future bishops sharpened their teeth there, it did not pay its way and by 1616 was in serious financial trouble. James came to the rescue by ordering the bishops to do so. Most of the little that came in was consumed by the cost of raising it. The college then diverged from royal policy by attacking Arminians as quasi-papists. Cromwell killed it. Not a stone now remains.49

While the Academ Roial was under lethargic consideration, the greatest projector of the time returned to James for support for what he called the Great Instauration, or root-and-branch renewal of the natural sciences. Francis Bacon had tried James just after the Gunpowder Plot, to no avail, although he had taken the trouble to write out a lengthy description and classification of the sciences needing renovation. This was the Advancement of Learning (1605), which coincided, unfortunately for Bacon, with the new king’s launch of the projects that produced the King James Bible and Chelsea College. Even a rich divine-right king might have hesitated, however, over Bacon’s plan to take over three public schools and three Oxbridge colleges.50

But who other than James could bring it about? “There hath not been since Christ’s time any King or temporal Monarch, which has been so learned in all literature and erudition, divine and human.” Not since Hermes has there been such a miracle: “the power and fortune of a king, the knowledge and illumination of a priest, and the learning and universality of a philosopher.” James’s rare conjunction of admirable traits must be celebrated by a marker as permanent as possible in this our world of flux and transition, by some “solid work, fixed memorial, and immortal monument.” What better way to assure the quasi-immortality of the new Solomon than by directing the winds of learning, by preserving and improving knowledge?51

Bacon offered James three targets or “works of merit” in this line: libraries, universities, and scholars. Universities, with their privileges and endowments, provide quiet and privacy for the thinking man; libraries, shrines for the repose of the relics of learning; scholars, worthy subjects of reward. The works of merit of previous princes left the instruments of learning imperfect: the universities focus on the professions at the expense of the sciences natural, civil, and moral; scholars’ salaries are too small and mean; and libraries, fixated on books, do not supply the experimental apparatus essential for advancing knowledge. A useful set of experiments costs money. In one of his striking strained analogies, Bacon told James that inquiring into the kingdom of nature was like spying on fellow rulers; “and therefore, as secretaries and spials of princes and states bring in bills for intelligence, so you must allow the spials and intelligencers of nature to bring in their bills, or else you will be ill advertised [informed].”52

The advancement of learning is not a matter of money only. The work also needs the guidance of a prince able to understand his investment, to perceive where learning is deficient, and to engage competent people to prosecute underdeveloped sciences. Bacon takes James on a “general and faithful perambulation of learning, with an inquiry what parts thereof lie fresh and waste, and not improved or cultivated by the industry of man.” In their long walk, which constitutes most of the Advancement of Learning, Bacon notices the barrenness of the fields they pass, but does not stop to improve them; “for it is one thing to set forth what ground lieth unmanured, and another thing to correct ill husbandry in that which is manured.”53 Not knowing how much manure he would be required to hear or buy, and perhaps for other reasons as well, James declined to patronize the Great Instauration.

After rising to Lord Chancellor, Bacon prepared a clearer diagnosis of the illness of learning and its cure, a Novum organum (1620), a new method. The cure was to begin with the compilation of the necessary data, or “experimental natural histories.” The effort demanded more manpower, experiments, machines, and travel than appeared from the Advancement of Learning. Bacon tried James again with the rhetoric he had employed unsuccessfully in 1605. The Great Instauration was the sort of thing Solomon would have done, if he had had a Bacon, and therefore a project worthy of Your Majesty, “who resemble Salomon in so many things—in the gravity of your judgments, in the peacefulness of your reign, in the largeness of your heart, in the noble variety of the books you have composed.”54

James liked the general idea as described in the preface to the Great Instauration, but had not the patience to absorb the details.55 In the end, Bacon could only draw up a blueprint of a utopia located on an island in a distant sea. Solomon’s House, the utopia’s wellhead, employed dozens of savants arranged like bishops in hierarchical ranks to seek information, compile natural histories, do experiments, develop theories, and make medicines and machines. He died before he could specify how Solomon’s House could be transported from its island to the Stuarts’. Arundel made a partial answer by providing in his will for room, board, and clothing for six Solomons who had the qualifications of being poor, honest, and unmarried. They would have a good supply of books “and convenient roomes to make all Distillations, phisickes, and Surgerie.”56 Their works, if any, are not recorded.

Had James supported the academies proposed to him, his Academ Roial would have anticipated the Académie francaise (1635); his Society of Antiquaries, the Académie des inscriptions (1663); and his Solomon’s House, the Académie royale des sciences (1666). But he left his court without even the services of an astronomer, such as the emperor provided at Prague in Kepler and the Grand Duke of Tuscany at Florence in Galileo.57

Building

When fire destroyed his Banqueting Hall in 1618, James commissioned his Surveyor General to replace it with a modern building free from the discomforts of the shabby warren of Whitehall, a new fresh palace worthy to receive the Spanish princess he had set his heart on.58 Jones decided on a freestanding Palladian town palace in the shape of a double cube (length 110 feet, height 55 feet); construction began in 1619 and ended three years later, ready for the princess who never came. Although Wotton condemned the Corinthian and Composite capitals on the facade as gaudy Catholic, most observers judged the Banqueting House a great success. “If all the Books of Architecture were lost, the true art of building might be retrieved from thence.”59 James had his portrait painted in front of a detailed representation of it (Figure 20).60

Figure 20 Paul van Somer, James I of England. The king is shown standing in a window of Whitehall with the almost finished Banqueting Hall in the background (1620).

Jones’s masterpiece received its finishing touch in 1635 with three huge ceiling paintings by Rubens. They celebrate good King James as a unifying Solomon who brought together the Crowns of England and Scotland; as an irenic Solomon who lavished Peace and Plenty on both; and, in the great oval centerpiece, as a dead Solomon who went to heaven in the company of Justice, Faith, and Religion. The paintings required a sacrifice beyond payment of £3,000 to the artist. Masques and plays could no longer be acted there because the smoke from the torches illuminating the performances might spoil the paintings.61

The coincidence of the start of Jones’s great Palladian hall with the inauguration of the Mortlake tapestry works, and with Prince Charles’s purchase of Raphael’s cartoons for hangings depicting The Acts of the Apostles, suggests either a grand design or unusual luck. Several sovereigns, notably Christian IV and Henry IV, had set up or encouraged tapestry works in connection with major building projects. King James may have destined Mortlake products for new state apartments and for the Banqueting House, where Mortlake’s Acts of the Apostles did hang on state occasions. Hiring the “Titian of tapestry” (our Cleyn) to decorate the Banqueting House of a king of England with tapestries designed for a pope of Rome, and engaging the Catholic Rubens to paint its ceiling with a celebration of the Protestant James, exemplified the religious–artistic miscegenation of the early Stuart courts.62 Rubens’s paintings, Jones’s building, and the ghosts of Cleyn’s tapestries make a powerful symbol for those who can read it. These were the last emblems of his reign that Charles saw before stepping out of the Banqueting House onto the scaffold, where he became a martyr to his father’s teaching that he was “a little God to sit on his throne, and rule over other men.”63

Queen Anna’s Masques

The brave new Queen of Scotland, scarcely 16 years old, entered her uncomfortable capital of Edinburgh on May Day 1590, accompanied by 36 dames on horseback and an entourage of 200. The welcoming speeches, of which she could not have understood much, included one by Ceres, who addressed her primly in Latin, and another by Bacchus, who, more to the taste of her new subjects, “[sat] upon a puncheon of wine, winking, and casting it by cups full upon the people.”64 These were not the manners of the German princes her parents had tried to imitate. Anna had some financial resources, however, which allowed her to improve her immediate surroundings; and she might have made an austere home for the muses in Scotland had James owned all the property he gave her.65 In 1599 and again in 1601, she defied killjoy ministers by bringing in a traveling troupe of English actors. Perhaps the setting of Hamlet (published in 1602) with its many references to then recent Danish history owed something to the parentage of the Queen of Scotland.66 Among her affronts to Calvinism, however, her encouragement of the theater paled against her covert conversion to Catholicism, which she underwent around 1600, despite her inaugural oath to “withstand and dispys all papisticall superstitiones, and quhatsumever ceremonies and rites contrair to the word of God.” The move to England in 1603 gave Anna greater control of financial resources and a circle of aristocratic ladies who patronized the arts. By the time of her death she disposed of a considerable income: £24,000 a year from her jointure, £13,000 from duties on sugar and cloth, and something from licensing foreigners to fish in British waters.67 Still she ended in debt. One reason for it, and the extravagance that made Bentivoglio doubt her piety, was the cost of her masques, her main contribution to English culture.68

These performances began with the queen and her ladies displayed, masked, in magnificent costumes on an elaborate stage. The cast proceeded to dance, by themselves and then with partners from the audience. All were mute: professional actors spoke and sang, and professional musicians played. Dancing was the centerpiece. The queen and her retinue spent much time in rehearsing, from two to five weeks, and much money on costumes, which might cost upwards of £300 each. Among the retinue wealthy enough to appear in several masques, the queen’s favorite, Alethea Talbot, deserves mention: as Lady Arundel, she would be a lavish and knowledgeable patron of painters.69

The masques highlighted dancing for its mundane pleasures and, for those seeking symbols, for its cosmic mimicry. The stars and planets dance to the music of the spheres, the elements continually change partners, sound is the fluttering of the air, and tides the choreography of the sea; only the solid earth stays put:

Although some wits enrich’d with learning’s skill

Say heav’n stands firm, and that the earth doth fleet

And swiftly turneth underneath their feet.

Either way, according to Sir John Davies, who wrote these words, the apparent motions of the stars invite us to dance, prove the nobility of dancing, and illustrate the concord of the universe.70 Davies’s interpretation of the universe as the domain of Terpsichore dates from 1596, when he enjoyed associations with Oxford and the London Society of Antiquaries.

The first of Anna’s English masques, Samuel Daniel’s Vision of the Twelve Goddesses, marked the high point in the play-filled Christmas season of 1603–4, when James, wishing to initiate his reign properly, entertained foreign ambassadors as well as his Scottish favorites and English courtiers. Invitations were scarce and prized: and, since not all ambassadors received them, the Vision, like all Anna’s masques, had a political edge.71 In her second play, Jonson’s Masque of Blackness (January 1605), her company appeared blackened, as daughters of the god of the Niger, who wanted them whitewashed—a process that could be accomplished only under the scarce sun of Britannia. The audience shuddered to see their English roses blackened and disliked the play (Figure 21). Jonson and Jones redeemed themselves in their next try, The Masque of Beauty (January 1608), in which the nymphs, whitened and bejeweled, and four others wanting bleaching, returned to Britannia on a floating island. This piece of stage wizardry in the Italian style also carried an orchestra and figures representing the eight elements of feminine beauty, which prudence deters itemizing. No doubt the French ambassador was outraged that his Spanish counterpart received an invitation and he did not. He missed a good show. James liked it so much that he demanded encores and, despite its cost of £3,000, asked Anna to provide another masque for the following year.72

Figure 21 Inigo Jones, sketch of a participant in Jones’s and Jonson’s Masque of Blackness (1605).

For £5,000 she supplied The Masque of the Queens, which introduced the antimasque, a prelude or interlude intended by its quirkiness to bring out the sober beauty of the main action. Antimasques also offered opportunity for metaphorical political commentary with relative impunity. The antimasque of Queens centered on a smoke-filled pit from which emerged thirteen witches played by professional actors. The hag in charge introduces them—Ignorance, Suspicion, Credulity, Falsehood, Murmur, Malice, Impudence, Slander, Execution, Bitterness, Rage, and Mischief—who might have served as personifications of witch-hunters like King James. The witches boast storm powers, chant charms, and vanish with their Hell. In their place appears the House of Fame, whence twelve queens led by Bal-Anna ride forth in chariots, alight, and dance.73

Smoke-filled pits easily appeared when resin fell on an open flame and Hell’s mouths and dragons’ breath became pleasant and plausible with a little sal-ammoniac and brandy. Since torches and candles provided the illumination and reflectors multiplied the light, masques were literally smoke and mirrors.74 The optical effects combined with loud music to drown out stage machinery and perfumed perspiring bodies completed the assault on the senses. On the mind, however, the beauty of the costumes, status of the performers, and veiled intent of the playwrights imposed a compelling three-dimensional hieroglyph; or so said Daniel, following Jonson and anticipating Bacon, who recommended hieroglyphs and parables in general, “because arguments cannot be made so perspicuous nor true examples so apt.”75 Appreciating a masque, putting together the hieroglyphs as symbol, allegory, myth, analogy, celebration, or protest, took some effort. The chief hieroglyph in Anna’s performances is easily deciphered, however: women made the masque “the most developed courtly pastime and formal social occasion of the English Renaissance.”76

For her son Henry’s investiture as Prince of Wales in June 1610, Anna gave a masque written by Daniel, staged by Jones, and starring herself. Princess Elizabeth, acting in a masque for the first time, appeared as a Nymph of the Nile. Six months later it was Henry’s turn, in Oberon, the Faery Prince (New Year’s Day 1611), which he commissioned from Jonson and Jones. Oberon opened with some satyrs playing on a boulder as they awaited the arrival of the faery prince and his company on a couch drawn by two white bears. Simultaneously musicians sang a hymn of praise and reassurance to King James: “[He] in his owne true Circle, still doth runne ǀ And holds his course, as certayne as the sunne.” The prince then led his followers in their own geometrical courses. A month later Anna gave her Jonsonian masque, Love Freed from Ignorance and Folly, which required Cupid, chained by the Sphinx, to solve a riddle to save himself and eleven beautiful maidens of the morning. The riddle: find a world without a world where everything is done by a fixed eye that moves and whose power rests on the mixture of contraries never previously joined. Cupid instantly answers “woman.” Wrong. The Sphinx prepares to annihilate Love. Cupid tries again: “the King of Albion.” Right. Love’s recognition of the joint power of king and parliament vanquishes the evil Sphinx.77

The royals sat through many plays and masques, an average of twenty-five a year, most of them crammed into the holiday season between November and February. The sabbath presented no obstacle to these revels or to the abbreviation of costumes. “[Anna’s] clothes were not so much below the knee but that we might see a woman had both feet and legs, which I [Dudley Carleton speaking] never knew before.”78 Submitting to these entertainments could be grueling. In February 1613, having just seen two long performances, James could not stomach a third. In March 1615, on his first visit to Cambridge, he sat through four successive evenings of theater, three of them in Latin. One was George Ruggle’s Ignoramus, perhaps the most popular of academic comedies. James liked it so much he returned to Cambridge to see it again. Its fun depends largely on the broken Latin spoken by the lawyer Ambidexter Ignoramus and his clerk Dulman, who thus recommends the play:

O Lector Friendlie…tibi Wittum, tibi Jestaque plurima sellam

. . . . .

Hic multum Frenchum, quo possis vincere Wenchum

Hic est Latinum, quo possis sumere vinum.79

The tired plot employs a clever servant to prevent an old man (Ignoramus) from buying a young wife. Two fake priests accuse Ignoramus of diabolic possession for his unseemly lust and call out his devils by taking his legal terms to be their names. Ignoramus: if she married me she would have francum bancum. Priest: “Be gone, Francum Bancum.” Ignoramus: She would also have Infangthief, Outfangthief, Tac, Toc, Tol, and Tem, which, by the way, she would have had if she had married John Bankes. Priest: “How many there are of them! Be gone all of you…Come forth you evil spirits, whether you be in his doublet, or his breeches, cloak, drawers, pen, wax, seal, inkhorn, indentures, parchments …”80 James took great pleasure in the insults to the lawyers he blamed for the obstruction of his programs by parliament.

The lawyers railed at their treatment in Cambridge and composed many epigrams at the expense of scholars; but Gray’s Inn’s Masque of Mountebanks, performed before the king in 1618, struck instead at quack doctors.

This powder doth preserve from fate

This cures the Maleficiate

Lost Maydenhead this doth restore

And makes them Virgins as before.

The play also pokes fun at astrology. Physicians and surgeons relied on associations between zodiacal signs and body parts to determine times for bloodletting. The antihero of Ignoramus escapes gelding because the moon occupies the sign supervising the parts he would lose.81 Albumazar, the only play in English James saw in Cambridge in 1615, involves such deep concepts of astrology that its resume must be put off pending further instruction. The same consideration applies to Technogamia (1617), a tedious play written and performed by scholars of Christ Church, Oxford, in the summer of 1621, which has in its favor some references to the Copernican system. Notice of Jonson’s embroidery of Galileo’s observations of the moon into the news that lunarians are humans covered with feathers need not be postponed, however, and is hereby given.82

Invitations to entertainments continued to have political significance. At a masque given by Prince Charles in January 1621, the ambassadors of Tuscany, France, and Savoy being in attendance, and Charles and Buckingham competing in pirouettes, “the former Archbishop of Spalato, who daily advances in esteem and favour,” stood near the king among a swarm of lords.83 And it may be remembered that, soon after his arrival in England, George Conn was with the royal couple in Oxford at the performance of Floating Island.

Anna kept many musicians for her entertainments: a masque such as Oberon required around 60 instrumentalists and Triumph of Peace, the Inns’ potlatch of 1634, employed perhaps 100 musicians of whom 40 were lutenists.84 Many occasions besides masques needed singers. A refined evening with the queen might begin with an after-supper menu of French songs in her privy chamber before her closer friends withdrew to her bedchamber to hear “mr Lanier, excellently singinge & playinge on the lute.”85 Nicholas Lanier came from a family of Italian musicians close to the court; like them, he wrote music for masques and, like other artists with taste and connections, he improved the Stuart art scene by buying pictures abroad for patrons at home.86

Christian IV urged his sister to fill her palaces with art. She began modestly, with miniatures; her miniaturist, Isaac Oliver, led her to portraits, and on to landscapes and religious works, mainly by Dutch and Flemish artists.87 Eventually she included the sorts of Italian paintings recommended by Wotton and collected by Somerset and Arundel. Since Italian (and Spanish) art often depicted scenes too close to popery or vice to recommend it to Puritans, and religious paintings had no place in their ways of worship, Catholics were more likely to appreciate it than Protestants. As we learned earlier from Prynne, strict Puritans would not risk even portraiture for fear of creating golden calves from prettified women.88 Consequently many art agents were Catholics, and the great collections they helped to make during the reigns of the first Stuarts belonged to or were started by Catholics or Catholic sympathizers.89

Queen Anna stands high among them. Arundel qualifies twice or thrice: he acquired an interest in painting from his great-uncle, Lord John Lumley, a strong Catholic who spent time in prison for conspiracies until released to cultivate his accumulations of books, buildings, and art; Lumley’s large collection of paintings consisted overwhelmingly of portraits chosen rather for the sitter than for the painter. Lady Arundel, who began collecting with the help of Wotton and Jones, remained a Catholic after her husband’s conversion. “The chief lady of the court and kingdom” by Venetian estimate, she returned from Italy, after seeing to a proper Catholic education for her children, with Van Dyck in tow.90 Arundel’s great rival as a collector before Charles entered the competition was the Duke of Buckingham, who, though “illiterate” according to Wotton, knew how to get what he wanted.91 His closest female relatives, his wife and mother, were Catholics.

Prince Henry’s Projects

Prince Henry’s Puritanical streak and quick martial spirit, which made him the rallying point of English prudes and hawks, put him temperamentally and spiritually at odds with his father. But Henry cheerfully followed James’s advice to abstain entirely from the works of Buchanan and, if free to do so, would have done the same to most literature. His interests ran to practical subjects, to the uses of arms and horses, techniques of building, geography and architecture, modern languages, applied mathematics. After 1610, under the influence of Arundel and perhaps Jones, the Prince developed an interest in art. Henry had very firm and sober opinions for a boy of 16 and courtiers aplenty to promote them.92

Our interest in Henry’s short-lived initiatives and the men who served them lies in their likely impact on Charles, who idolized his elder brother. Two people in Henry’s entourage would be particularly important for Charles: Jones, who kept under Charles the office of Surveyor he had acquired under James, and Arundel. Charles learned less directly but more substantively from the applied mathematicians whom Henry retained: an Italian and a French architect, Costantino de’ Servi and Salomon de Caus, and two well-traveled English mathematicians, Edward Wright and William Barlow. They tutored Henry for several years. Although he did not attain an expertise in mathematics unbecoming a prince, he no doubt fully understood its elements.93 So did Charles.

Wright was an experienced navigator and champion of the Mercator projection, whose construction he simplified in a work, Certaine Errors in Navigation (1610), which he dedicated to Henry. The prince had a strong interest in exploration and colonization, and hence in navigation, and in mathematical instruments and mechanical automata like Drebbel’s perpetuum mobile and Wright’s clockwork celestial automaton.94 That he cultivated an interest in astronomy may be inferred from his purchase of an expensive telescope and his request to the Florentine Resident, Ottaviano Lotti, for a copy of Galileo’s Sidereus nuncius. Lotti complied and added a music book useful for masques by Galileo’s father Vincenzo, and (a perceptive diplomat) a shipload of wine for King James.95

Henry never traveled abroad but surrounded himself with men who did. Coryate’s Crudities (1611) gained its author appointment as court historiographer. Henry’s chamberlain, comptroller, and chief tutor extended his vicarious Italian experience. He admired the spirit of Venice and would have fought for it against Rome had war come and James let him—an infatuation that left its trace in the Latin translation of Sarpi’s Trent later made by Henry’s chief tutor Adam Newton for the use of anti-Roman theologians.96 Henry’s precocious understanding of the value of spectaculars in promoting royalty also drew his attention to Italy. The ceremony by which Venice annually married the sea was a benchmark; but, for displays more applicable to the terra firma of England, Florence took the prize. Henry dispatched one of his Italian hands, Sir John Harington, the translator of Galileo’s favorite piece of literature, Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, to Florence to observe the blowout around the wedding of Galileo’s student Cosimo II to Maria Maddelena of Austria in 1609. Henry probably had an eye to entertainments for his upcoming investiture as Prince of Wales and for his wedding, already under discussion, with an Italian princess.97

It was said that de’ Servi’s main job was to keep Henry in mind of things Florentine when thinking of marriage. He was something of a portraitist, for he had studied with Santi di Tito, whose sitters included Galileo; and among de’ Servi’s few accomplishments in England was a portrait of Prince Henry.98 De Caus was more engineer than courtier. He worked for Anna and Henry and then for Elizabeth, primarily as a designer of geometrical gardens; the beautiful example he made for Elizabeth at Heidelberg was one of the great losses she suffered when driven from the Electorate. While with Henry, de Caus completed a book on drawing and optics, La Perspective avec les raison des ombres et miroirs (1611), compiled from lessons he had given the prince, and designed all sorts of hydraulic machinery for Henry’s palace at Richmond.99

When Henry began to express an interest in art, he received gifts from many sides, notably Giambologna sculptures from the Grand Duke of Tuscany. These lively statuettes seem to have made a strong impression on Charles as well as on his brother. Henry soon was buying paintings through Wotton, Carleton, and others, in such numbers that Jones had to build a small gallery for them.100 Additional bespoke accommodation was needed for the many books Henry received as presents, by purchase, or through inheritance. The largest part of his library came from the childless Lord Lumley, whose collecting had privileged books on genealogy, history, antiquities, and natural science. Henry discarded law and theology and augmented the rest. The mathematician Wright was to have been Henry’s librarian. But the books passed, as did the artworks, to Charles, who moved the center of interest to paintings.101

The Caroline Couple’s Entertainments

Calculations

If he was indeed the good mathematician he was reputed to be, Charles would have been familiar with the military compass, a standard calculating instrument designed by Galileo and others for scaling up drawings or reckoning interest.102 He no doubt understood the method of logarithms invented by his father’s protégé John Napier as simplified by the same Edward Wright who had made Mercator manageable; for Charles in his turn patronized a logarithmic inventor, Richard Delamain, a mathematics teacher with a gift for self-promotion. Delamain had his invention made in silver as a New Year’s gift to Charles in 1630. The king accepted it and the dedication of Delamain’s book, Grammelogia (1631), which described its construction and use.103

The instrument had log scales for sine and tangent as well as for the natural numbers, and so was useful in astronomy; and, as it also had proportional scales for integers, it could do the simpler problems treatable by Galileo’s compass. The very first worked example in Grammelogia calculates interest at the 8 percent Charles typically paid. But the interest of the instrument for our story lies in the squabble it unleashed when William Oughtred, a mathematician in Arundel’s circle, claimed credit for its invention. Since Delamain had studied with Oughtred, he very probably took the idea from him; and he certainly pinched the design of a second instrument, a pocket “horizontal quadrant” or handy astronomical calculator, from his teacher. This he reduced to practice and rushed to market, taking care again to give Charles a sample in silver.104

Oughtred called foul. Delamain was not only a thief but an ignoramus (he had taught him!), who probably did not know how the instruments worked and certainly did not bother to explain them. There is no reason to criticize me, Delamain protested, for not bothering my clientele with the theory of the instrument; the nobility and gentry had no time for “theoretical…demonstrations.” They wanted to know how to survey their estates and to estimate the amounts of timber on their lands and wine in their casks; and for them Delamain’s instructions sufficed. For Oughtred they were “onely the superficiall scumme and froth of Instrumentall trickes and practises.” The exchange was not unprecedented. Competing for the then new (in 1619) Savilian chair in geometry in Oxford, the practical mathematician Edmund Gunter showed Savile his dexterity with instruments. “Said the grave Knight, ‘Doe you call that reading Geometrie? This is shewing of tricks, man!’”105

Gunter did not get the job. He could not find the answer Delamain would give to Oughtred: go-betweens were needed to reduce difficult concepts to art and deliver them to users without the “rigide Method and general Lawes [that] scarre men away.”106 Liking instrumental tricks and practices, Charles gave Delamain a patent on the circular slide rule, made him an engineer in the Office of Ordnance, and employed him as a tutor to the royal children. The king set great store by his engineer’s silver quadrant. He carried it about his person until just before his execution. He then directed that it be given to his younger son, the future James II, who would need every help to find his way.107

Charles took a strong interest in architecture and liked to review the plans of Surveyor General Jones. Their grandest project, a magnificent new palace of Whitehall, turned out to be well beyond the royal means. A lesser project that succeeded deserves mention for its subtle combination of art, politics, and religion. This was the church of St Paul’s, Covent Garden, said to be the first entirely new Protestant church built in England after the Reformation.108 It still stands as the dominant structure in the piazza that Jones designed against the royal policy that forbade increasing the housing stock of London lest country aristocracy and gentry reside there with nothing to do between parliaments but plot and carouse. Despite this policy, Charles allowed development of Covent Garden with a square surrounded on two sides by townhouses that unwelcome newcomers, already a subject of comedy, soon occupied.109

The developer was the entrepreneurial fourth Earl of Bedford, who bought, for a fine or fee of £2,000, a license to build adjacent to the church he had constructed on his London estate at Laud’s request. Charles insisted that the church have a portico. Being a frugal Calvinist, Bedford choked over the extra expense of the portico and asked Jones to build as cheaply as possible. Hence its chaste style, which did not suit Laud’s ideas of the Lord’s House. Nor did Jones’s placement of the church on the west side of the piazza so that its entrance faced east, where the altar belonged. The archbishop was not amused. He ordered the entrance sealed and the altar placed against it.110

Addictions

Being indifferent to paintings and perhaps ignorant of their value, James had allowed the collections of Henry and Anna to pass intact to Charles.111 The prince sharpened his appetite for art in competition with Buckingham, and both of them were energized by the acres of paintings in the galleries of Charles’s prospective brother-in-law Philip IV. As king, Charles augmented his holdings inexpensively with presents from other sovereigns, like the King of Savoy, and ambitious courtiers such as Carleton, Cottington, and Porter.112

A great opportunity for more soon presented itself. The needy Duke of Gonzaga decided to sell his important collection. Daniel Nijs succeeded in buying it, much to his surprise. “In this business I feel I’ve had divine assistance, otherwise it would have been impossible to pull it off.” He had managed to outmaneuver the Grand Duke of Tuscany, a rich Genoese consortium, and the citizens of Mantua. Divine assistance is not dependable, however. Many of the Gonzaga paintings degraded during shipment and Charles, declining to honor the agreed price, bankrupted Nijs. Charles delighted in his undamaged Gonzaga paintings, which, when added to what he had, made his collection one of the best in Europe, “the culminating point of Italian influence in England,” the translation of “Italy (the greatest mother of Elegant Arts)” to Albion. As he rose to respected connoisseur in the art world, Charles sank to sinful spendthrift in the Puritan universe.113

Charles shared his Italianate sin with a few connoisseurs like Arundel. The degree of their intimacy and addiction may be gauged by the king’s rushing to the earl’s house to see the pictures he had brought back from his failed mission to Vienna in 1636. Conn was present at one of their discussions. Charles: I have learned of a miracle: the earl (Arundel) has given a Holbein to the Grand Duke (of Tuscany). Conn, who knew that it was impossible to extract anything from Arundel: the earl could perform the same miracle thirty times since he has thirty Holbeins. Arundel: I do not have the power. Conn: You have freedom of will. Arundel: “[I am] most willing to support that doctrine except in the matter of giving away pictures.” Conn diagnosed Arundel as too addicted to his collections to do much to help Catholics; all his conversation was about pictures, “while I am no good for these objects, unless to dust them.”114

With Conn’s help, Charles obtained several coveted pieces from Italy, most famously a bust of himself sculptured by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. This coup required the approval of Pope Urban; an art of the Vatican was the gift of Vatican art.115 Urban gave his permission for Bernini to proceed with Charles’s bust. That left the technical problem that the sculptor had never seen his subject. Van Dyck solved it by painting a triple portrait of Charles on the same canvas, two in profile and one face on. Bernini then worked his magic. The royal couple received the king’s bust with rapture, and, when Conn returned to Italy, gave him a commission and drawings for a similar representation of the queen. It did not materialize. Charles’s bust lasted longer than he did, but it also died violently, in the fire that destroyed Whitehall in 1698.116

The Barberini continued their seduction by art with works by Leonardo, Veronese, Correggio, Andrea del Sarto, and Guido Reni. They were circumspect: Henrietta Maria complained of one of their shipments that it contained no religious paintings. Nonetheless, the chapel Inigo Jones made for her in Somerset House opened with great fanfare in 1635 under pictures supplied by the pope.117 He also sent her rosaries and a crucifix embossed with Barberini bees rendered in diamonds, “a priceless favor…my most precious possession.”118 The royal couple delighted to show their favorite paintings to Conn. Charles so forgot himself in exhibiting them that once he kept the glories of England, the Knights of the Garter, waiting while he dallied in his galleries with the pope’s agent.119 The king extended a similar familiarity to Conn’s successor, whose residence he visited to see portraits of Urban and the cardinal nephew. Charles then remarked that he regarded the pope with “the esteem and respect that should prevail among all princes” and effusively praised the cardinal, who had been kind to important English travelers.120

It took money and taste, but not much imagination, to assemble a good collection of finished paintings. With a push from Lanier, Charles and his emulators came also to value preparatory drawings. As Arundel’s librarian Franciscus Junius put it, drawings allowed the collector to follow “the very thoughts of the studious Artificer, and how he did bestirre his judgment before he could resolve what to like and what to dislike.” Perhaps Wotton had such drawings in mind when reaching the counterintuitive insight that it is almost harder to be a good critic than a good artist. The artist can change his mind as he proceeds; the critic, especially if a buyer, must conclude quickly and definitively; “the working part may be helped with Deliberation but the Judging must flow from an extemporall habite.”121

Charles was a major patron as well as collector of art. “The most splendid of your Attainments [so Wotton wrote his sovereign], is your love of excellent Artificers and works.” Most of these artificers were foreign. Francis Cleyn was the foremost if judged by expenditure on product, for his ongoing labors at Mortlake probably cost more than all the paintings and sculpture Charles commissioned from Van Dyck, Bernini, Daniel Mytens, Gerard Honthorst, Orazio Gentileschi, Orazio’s daughter Artemesia, and Arundel’s protégé Wenceslas Hollar. The only major Italian artist in Charles’s employ, Gentileschi, acquired by Buckingham from the Dowager Queen of France in 1626, did more than paint: he probably acted as an intermediary between Spain and England as Rubens did and certainly sent the Vatican information about the Caroline court. The scant representation of resident Italian artists records their disinclination to live with rain and heretics. No doubt also they disliked Charles’s bad habit of postponing payment and reducing prices. He cut a bill from Van Dyck for £1,295 for twenty-four pictures in half in 1638, although he then owed the painter £1,000 on the retainer he had not paid for five years.122

Foreign artists tended to live in ex-pat communities in districts of the city like Blackfriars that lay outside the jurisdiction of the Painters–Stainers Company.123 Charles kept these guild-free painters busy painting his guilt-free person. Van Dyck outdid them all by portraying Charles bursting through an archway effortlessly controlling a huge horse, his adoring groom by his side, a baton of command in his hand (Figure 22). This persuasive depiction hung so as to give the impression that Charles was riding into one of his galleries through its end wall. Other renditions by Van Dyck emphasize Charles’s domestic virtues. As Wotton, who knew something about the political value of portraits, observed, Charles was made to appear a model of chastity and temperance (which he was), of steadiness of resolve (which he was not), and of “heroicall ingenuity” (which his foreign policy exemplified).124 In these repetitive portraits Charles tried to achieve what ancient kings had done by multiplying their statues. As Wotton put it, “[the portraits] had a secret and strong Influence, even into the advancement of the Monarchie, by continuall representation of vertuous examples; so as in that point art became a piece of State.”125

Figure 22 Antony van Dyck, Charles I (1633), commander of horses and men.

Practicing his preaching, Wotton liked to hand out portraits of Sarpi copied from the one he had smuggled out of Italy. Known recipients were Nathaniel Brent, who, having accomplished the feat of publishing Sarpi’s Trent in English within a year of the appearance of De Dominis’s Italian edition, and having performed equally well in other projects of a political–religious character, had climbed to the wardenship of Merton College in Oxford. A late recipient of what Wotton called the “true picture of Padre Paolo the Servita, which was first taken by a painter whom I sent unto him from my house then neighbouring his monastery,” was the Provost of King’s College, Cambridge, Samuel Collins. His copy had a motto devised by Wotton: Concilii Tridentini Eviscerator, “The Eviscerator of the Council of Trent.”126 Just such a picture now hangs in the Upper Reading Room of Oxford’s Bodleian Library (see Figure 7).

Masquerades

Court plays and masques offered another route by which royalty could exaggerate its merits. Charles and Henrietta Maria sat through the same yearly average of these hieroglyphs as had James and Anna and may have enjoyed them more, since the Caroline variety was both spunkier and more sycophantic, “more exotic and prodigiously expensive,” than the Jacobean. Much of the difference was owing to Henrietta Maria. In her first English theatrical season, 1625–6, she not only danced but also spoke; those not scandalized by her forwardness admired her recital, from memory, of hundreds of lines of poetry. The teenage queen must have been in good shape; she could rehearse for twelve hours before a performance lasting seven or eight. After one of these athletic feats Prynne announced his famous equation, “woman actors, notorious whores.”127

To his iconic stature of chaste lover, model father, and alpha male, Charles added man of peace, to which he had a valid and compromising claim. Poverty and prudence advising against a war for international Protestantism, the court made the best of the situation and celebrated Charles as pacifier. The Banqueting House often served as auditorium, Inigo Jones as set designer, and Ben Jonson as skit writer. The final tableau usually referred to peace, which did not prevent Jones and Jonson from going to war; their collaboration ended with the masque given for Charles by William Cavendish in 1634, Love’s Welcome at Bolsover, which parodies the king’s Surveyor as Iniquio Vitruvio.128

The masques often conveyed their panegyric with the help of astronomical symbols and motifs. Representing the king as the sun was common coin, as we can read on one stamped to commemorate Charles’s entrance into London in 1633, after his crowning in Scotland. Sol rediens orbem, sic rex illuminat urbem, “like the dawning sun the King illuminates the city.”129 A double portrait by Honthorst, Apollo and Diana (1628), makes the obvious connections between the sitters and the luminaries. The translation of the entire court into the Heavens, however, was something unusual. It happened in Coelum britannicum, “the most spectacular, elaborate and hyperbolic of the Caroline masques,” written by Thomas Carew and staged by Inigo Jones in February 1633. Its premise: Olympian Jove looks down at the connubial faithfulness of the royal couple, feels ashamed, and resolves to clean up his act.130

Jove first purges the Heavens of every constellation representing his love affairs. The Bull and the Swan have to go, and the Bear, Dragon, Hydra, Centaur, and even the Virgin, compromised by lying between a Lion and a Scorpion. To accomplish the burdensome task, Jove appoints an “Inquisition” taxed with removing all celestial improprieties and “all lustfull influences upon terrestrial bodies.” Like Urban’s Inquisition, Jove’s is to “suppresse…all past, present, and future mention of those abjured heresies.” Having thus arranged for the conversion of the home of the Gods into a “cloyster of Carthusians,” Jove commands Mercury to make a “total eclipse of the eighth Sphere”—that is, to expel all the stars, an event, as Mercury rightly says, unforeseen by earth-bound prognosticators, “no, nor their great Master Ticho.”131

Now the celestial regions must be refilled with asterisms more suited to them than the beasts just evicted. Personifications of the spirits that dominate human life put themselves forward. Mercury and the greatest nitpicker of the gods, Momus, examine each in turn: Plutus (Wealth), who claims to hold virtue by a golden chain and to have supplied Jove with the coins showered on Danae; Paenia (Poverty), who argues that her kingdom is far larger than Wealth’s, and contains many poets and intellects; Hedone (Pleasure), who also excels Wealth, being the reason for acquiring riches; and so on. None passes scrutiny. The obvious solution arrives in personifications of the Genius of Britain and its three kingdoms, who emerge from a mountain on stage, and of Religion, Truth, Wisdom, Concord, Government, and Reputation, who descend on clouds. By adding to these the worthies of Britain, past and present, Mercury has enough virtuous candidates to replace the thousand stars listed by Ptolemy.132 No member of “the eighth of our Coelestiall Mansions, commonly called the Starre-Chamber,” is among the nominees. The requirement of virtue rules them out.133

The strikes at the high court of Star Chamber and the Inquisition aimed jointly at English censorship of the stage and Roman control of thought. Galileo’s trial and sentencing took place between the performance and the printing of Coelum britannicum. That is not its only Italian reference. Carew took his plot from a dialogue, Spaccio della bestia triomfante, “Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast,” which Giordano Bruno had published in 1584 during his stay in England. It is so thorough a compilation of Bruno’s quirks and heresies that the Roman Inquisition featured it in its summary of his trial. In Bruno’s plot, Jove decides on reform because his “jaded strength and enervated manliness” disqualify him from repeating his former exploits. He orders Cupid to put on some clothes, Bacchus to give up debauchery except on Saturday nights, and Vulcan to stop working on holidays. He gets the gods to agree to the purge and, with the help of Momus and some input from Mercury, chooses the new celestial residents.134

Bruno’s Jove substitutes Truth and Prudence for the Bear and the Dragon, which he sends to Britain. Wisdom and Law advance to the former seats of Cepheus and Boötes. Thus personifications of Good Things fill the Heavens: no king or courtier, as in Carew’s adaptation, ascends so high. Jove leaves Corona Borealis in place as the crown of the champion who wipes out the Calvinists, a “stinking filth,” whose souls Bruno condemns to spend 3,000 years migrating from one metempsychotic ass to another.135 Carew’s masquers who knew that his plot derived from Bruno might have shuddered at the thought of Jove’s Roman-style Inquisition.136 Charles would not have been among them. If we credit the report of a Catholic newsmonger, the king regarded the Inquisition as a useful tool for divine government, “it were to be wished that it were in all parts of Christendom to bridle mens tongues.”137

Between the Bishops’ Wars, Jones diverted the court with storms, mountains, cityscapes, heavenly spheres, populated clouds, and flying chariots. Like contrivances appear in the last court masque, William Davenant’s Salmacida spolia (January 1640), in which, unusually, both the king and the queen performed. In the ancient story, a tavern-keeper by the sweet spring Salmacis civilized (some say emasculated) barbarians by serving them its waters; by strained analogy, Charles will conquer the idiots who oppose him by overcoming them with wisdom and patience. There is a nice astronomical image. “You that so wisely studious are ǀ To measure and to trace each Starr,” look where the true light is, down here, where the royal tavern keeper dwells. Lower your telescopes, “Levell your perspectives.”138 In an earlier masque, Britannia triumphans (1638), Davenant had directed king and courtiers by a more elaborate celestial metaphor.

Move then in such an order here

As if you each his governed planet were

And he moved first, to move you in each sphere.

The ranks of courtier dancers, inspired by “the wonders of his virtue,” formed figures reminiscent of the constellations.139

Instruments were a common way of keeping astronomy in playgoers’ minds. Among many humdrum examples of telescopes used to peer into ladies’ closets, we have such marvels as Galileo’s glass capable of firing a ship at night by concentrating moonbeams and the more remarkable lens that allowed a vision of God’s throne.140 A playwright needing a representation of genius might well choose an astronomer whose mind, instructed by his observations,

Has pierc’t into the utmost of the Orbes

Can tell how…the Sphaeres are turned, and all their secrets

The motion and influence of the starres …

The causes of the winds, and what moves [!] the earth.141

This accomplished astronomer appears to have been a Copernican.

As the Personal Rule ran into trouble in Scotland, the Caroline masques promoted a picture of Camelot-in-being that increasingly diverged from reality. They insisted on the king’s wisdom in governing and his divinely ordained prerogatives. Henrietta Maria’s masques, The Temple of Love (1635) and Luminalia (1638), both by Davenant, portray her Catholicism and Charles’s Anglicanism implausibly as two peas in an irenic pod.142 Aurelian Townshend’s Albion’s Triumph (1637) stresses cultural refinement, especially in painting, which showcased the gap between the king’s self-image and the condition of his realm. Charles’s hazy distinction between fantasy and reality helped him to play the final part in his tragedy. An eyewitness to his execution thought that he “came out of the Banqueting House on the scaffold with the same unconcernedness and motion, that he usually had, when he entered it on a Masque-night.”143

Although presented but once or twice to a small audience, the Caroline masques had a wide circulation by report and in print, and the repetition of their themes, almost as a liturgy, suggested the height to which king and country could aspire. By pointing to gaps between Whitehall and Camelot, panegyrics might encourage better behavior.144 Strode’s Floating Island (1636), reviewed earlier, is an example. It contains many apt jibes at favorite targets: monopolies, judges, the godly, Puritans, physicians, playwrights. Reversing direction, it attacks parliament and defends ship money. Before Charles–Prudentius temporarily sets aside his crown, he experienced efforts to blunt his prerogatives, reform his state, determine his expenditures, appoint his ministers, and refuse him supplies. Recognizing that the “Tumult, Lust, Debate, and Discontent” affecting his island might tempt foreign powers to attack it, he had collected ship money as the means to build a powerful defensive navy. Oh, “thou god on earth”! The island remains afloat. “Our scene which was but Fiction now is true ǀ No King so much Prudentius as you.”145

James Shirley’s Triumph of Peace (3 February 1634), also mentioned earlier, struck at obscure inventions on which projectors hoped to obtain monopolies: a bridle that keeps a horse from tiring, a device for a day’s walk under a river, a means of raising poultry on carrot scrapings. These projects are as idiotic as the quixotic knight and squire who, in the elaborate antimasque, attack a windmill.146 Charles did not object to attacks on monopolies and other abuses provided they did not come too near to his. He thought Shirley’s Gamester (February 1634), which digs at courtiers, one of the best plays he had ever seen. Since he suggested the plot, it must indicate his taste.