Just like space flight, early balloon flight offered military as well as metaphysical prospects. Cavallo’s dream of scientific ballooning was soon displaced by prospects of a more warlike kind. Benjamin Franklin had warned Sir Joseph Banks of this possibility, and such signs of the times were recognised by many contemporaries, including Banks’s clever younger sister, Sophia. She had begun to make a collection of balloon memorabilia, which she stuck into an enormous red-leather folio scrapbook especially purchased for the purpose. It would eventually run to over a hundred items.1 One of her earliest specimens was a British cartoon, dated 16 December 1784, entitled ‘The Battle of the Balloons’.

illustration credit ill.53

This shows four balloons, two flying the French fleur de lys and two the British Union Jack, manoeuvring for aerial combat. Their crews are armed with muskets, but also, more menacingly, with broadside cannons. Their muzzles point through portholes cut in the balloon wickerwork.2 Here the balloon is already conceived of as a weapon of war, comparable to the navy’s ships of the line.

Sophia also had an eye for many of the more eccentric examples of balloon propaganda. One set of this type was ‘Mr Ensler’s Wonderful Air Figures’, in which balloons were constructed in various animal and mythological shapes, such as the ‘Flying Horse Pegasus’. Some of these figures were intended to be provocative, like the giant ‘Nymphe coiffée en ballon et habillée à la Polonaise’. The Frenchified style of this description suggests sexual mockery. Then there was the bluffly patriotic ‘Mr Prossor’s Aerial Colossus’, showing an enormous ‘Sir John Falstaff’ floating defensively above the Dover cliffs.3 Such inventions were probably pure design fantasies, or at the most models, never actually manufactured full-size. But they suggest how balloons would become powerful forms of imaginative propaganda later, in the nineteenth century.*

* The tradition of fantasy shapes still flourishes in modern hot-air ballooning. At the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta in October 2010, I saw everything from a Pepsi-Cola can to Mickey Mouse, Darth Vader and Airabelle the Cow with her Beautiful Udder. Why do giant ‘air sculptures’ hold such a perennial fascination? There is something dreamlike about them; they are almost ‘thought-sculptures’. I have never seen one inspired by the human form – e.g. a Venus de Milo balloon; they are usually inspired by cartoon figures, publicity logos or friendly animals. Neither erotic nor monster shapes appeared popular. A humorous innocence seemed the most favoured mode, as if they had broken free from an illustrated children’s book. Actually the all-black Darth Vader balloon was weirdly menacing, and no one I asked at Albuquerque liked it. ‘Not such a great idea,’ seemed to be the general response. Although no one said so, I had the feeling that some balloonists thought Darth Vader might bring bad luck. They preferred the Force to be with them.

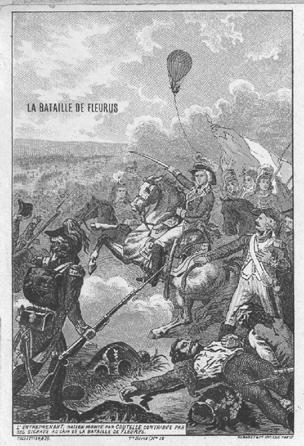

The first actual military balloon regiment, as Franklin had prophesied, was indeed French. The Corps d’Aérostiers was founded at the château of Meudon outside Paris on 29 March 1794. Less than three months later, on 26 June, the French army first made use of a military observation balloon at the Battle of Fleurus, against an Austrian army, and again a few weeks later at the Battle of Liège (where it was witnessed by the galloping Major Money). The balloon, manned on both occasions by a daring young officer, Captain Charles Coutelle, provided vital information prior to successful cavalry charges, and both battles were won by the fledgling French Revolutionary army.

The balloon school at Meudon was immediately expanded, and Coutelle showered with medals and appointed its commanding officer. He rapidly drew various lessons about military aerostation. First, that it was difficult to inflate a balloon with hydrogen on the battlefield. (Lavoisier was immediately coopted to invent a simpler method of generating hydrogen.) Second, that it was extremely hazardous to launch a tethered balloon if anything more than a light breeze was blowing. Held, kite-like and unnaturally on its cable against the force of the wind (instead of moving tranquilly within it), the balloon canopy would often thrash about and sometimes tear. Moreover, instead of gaining height it would fly horizontally and low. Above all, the basket would become highly unstable as an observation platform. Coutelle also remarked that it was not always easy to transmit really accurate and continuous observations from an airborne basket to a ground controller. Signal flags, scrawled messages or maps were rarely adequate. In most cases the aeronaut had simply to be winched back down, so he could deliver his appreciation verbally to a commander, in person and on the ground. Interestingly, it proved very difficult to get any commander to go up to see for himself.

illustration credit ill.54

But overall Coutelle believed that balloons promised considerable military value. He argued that, under the right conditions, a balloon would give an immense intelligence advantage to an army on the move, whether defending or attacking. It provided a wholly new tactical weapon, a ‘spy in the sky’ which could supply vital warning of troop build-ups and defensive positions, as well as preparations for attack or (equally vital) for retreat. Such observations could give a commander a decisive initiative in the field.

More subtly, a balloon was also an extraordinary psychological weapon. Because of its height, every individual soldier could see an enemy balloon hovering above a battlefield. By a trick of perception, this gave the impression to every soldier that he, in turn, could always be seen by the balloon. So everything he did was being observed by the enemy. There was no hiding place, no escape. The very presence of such a balloon above a battlefield was peculiarly menacing and demoralising. The enemy might certainly read an enemy soldier’s intentions, and even seem to read his thoughts. This alone made it a powerful military instrument. An Austrian officer was reported, after his army’s defeat at Fleurus, as murmuring, ‘One would have supposed the French General’s eyes were in our camp.’ His troops complained more angrily, ‘How can we fight against these damned Republicans, who remain out of reach but see all that passes beneath.’4

There was one unforeseen consequence of this. The French balloons quickly came to be universally hated by the opposing allied armies. As a result, they immediately attracted intense and sustained enemy fire, with every weapon that could be mustered, from pistols and muskets to cannon and grapeshot, directed at the observers’ basket. This, concluded Coutelle, made the military aeronaut’s position both peculiarly perilous and peculiarly glamorous.

The Corps d’Aérostiers eventually fielded four balloons, complete with special hangar tents, winches, mobile gas-generating vessels (designed by Lavoisier) and observation equipment. Coutelle would write a racy history of the Meudon balloon school, with modest emphasis on both the tactical and the amorous successes of the French military aeronauts. Wilfrid de Fonvielle later observed: ‘The favour of the ladies followed the balloonists wherever they went, which was not an unmixed blessing, and seems in the end to have contributed to the suppression of the corps.’5

With the declaration of war against Britain in 1794, many plays, poems and cartoons imagined an airborne invasion – both French and English – across the Channel. The Anti-Jacobin published invasion-scare cartoons featuring the French guillotine set up in Mayfair, and also extracts from a play purportedly running at the Théâtre des Variétés in Paris: La Descente en Angleterre: Prophétie en deux actes.6 There were some remarkable fantasy drawings of entire French cavalry squadrons mounted on large, circular platforms sustained by enormous Montgolfiers, sailing over the white cliffs of Dover. Nevertheless, the much-feared aerial invasion of England by Napoleon’s army never quite materialised.

In 1797 Napoleon triumphantly took the Corps d’Aérostiers with him to Egypt, counting on the very sight of balloons to put terror into the heart of his Arab enemies, as Hannibal’s elephants had once done in Italy. On 1 August 1798 Coutelle was preparing to unload all his gear outside Alexandria from the French fleet’s mooring at Aboukir Bay when Nelson sailed in at dusk. At the ensuing three-day Battle of the Nile, half of Napoleon’s ships were destroyed, and with them the entire Corps d’Aérostiers. The surviving aeronauts stayed on in Alexandria as technical advisers, like melancholy cavalry officers deprived of their horses. On his return home Napoleon disbanded the corps and the school at Meudon.

illustration credit ill.55

Nevertheless, rumours of a French airborne army invading Britain continued to be cultivated, and remained a powerful element in both French and British propaganda long into the nineteenth century. It was the aerial dream turned nightmare.

Civilian balloons and a different kind of competitive showmanship reappeared in France at the time of the Peace of Amiens in 1802. They were promoted by André-Jacques Garnerin (1770–1825), who launched his career by performing a spectacularly dangerous first parachute drop from a balloon over Paris’s Parc Monceau in 1797, when he was twenty-seven. As a young man, Garnerin had fought in the French Revolutionary armies, but he had been captured and incarcerated in the Hungarian castle of Buda for three desperate years. He spent his time there designing imaginary balloons to lift him out of the prison courtyard, or parachutes with which he could leap from the castle battlements.7 Finally released and returned to Paris, he turned his ballooning escape-fantasies into a full-time profession, and became head of the first of the famous French ‘balloon families’ (a role later inherited by the Godards).

Garnerin pioneered a new kind of balloon event: not merely the conventional single ascent, but a whole series of acrobatic displays, parachute drops and night-flights with fireworks. To add to the excitement, his dashing young wife Jeanne-Geneviève made the first recorded parachute jump by a woman in 1799. These shows attracted enormous crowds, and soon the Garnerins became famous throughout European capitals. Garnerin had numerous posters made of their flights, often showing him in heroic, eagle-like profile. Napoleon himself began to see that the balloon had a potential propaganda value even greater than the military one.8

The Peace of Amiens was barely signed when Garnerin daringly took his balloon show and parachute drops to London. His reception was surprisingly friendly, perhaps because he was joined not only by Jeanne-Geneviève, but also by his pretty niece Lisa. Garnerin’s first London ascent, from Chelsea Gardens on 28 June 1802, attracted a huge audience: ‘Not only were Chelsea Gardens crowded, and the river covered with boats, but even the great road from Buckingham Gate was absolutely impassable, and the carriages formed an unbroken chain from the turnpike to Ranelagh Gate.’9

illustration credit ill.56

Fearlessly launching in a near-gale, Garnerin flew along the line of the Thames, from the West End to the East End, directly over the City, and then out north-eastwards over the Essex marshes. He was effectively seen by half the population of London. Forty-five minutes later he crash-landed in Colchester, but came back the same day in a coach, gallantly announcing that his balloon had been torn to pieces – ‘we ourselves are all-over bruises’ – but that he would fly again within the week. Indeed, he next ascended from the old Lord’s cricket ground (on the site of the present-day Dorset Square) on 5 July. Advertising his flights with sensational engravings, Garnerin popularised night-ballooning and parachuting in England, and also the dangerous attitude that ‘the balloon show must go on’ whatever the weather.

The following year, 1803, Garnerin published Three Aerial Voyages, describing his London flights and including an amusing account, evidently intended for English readers, supposedly written by his wife’s cat: ‘Brought up under the care of Madame Garnerin, I may be said to have been nursed in the very bosom of aerostation, and to have breathed nothing but the pure air of oxygenated gas since the first moment of my birth. Hearing of my mistress’s intended ascension, I determined to share the danger …’10

illustration credit ill.57

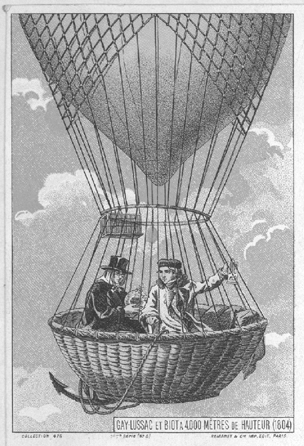

Scientific ballooning was not entirely forgotten in France. In August 1804 the mathematician Jean-Baptiste Biot and the chemist Joseph Gay-Lussac made a high-altitude scientific ascent, in the one war balloon Coutelle had succeeded in bringing back from Cairo to Paris. They tested the composition of the air in the upper atmosphere, and the strength of the magnetic field, but found no significant alteration from ground level in either. Biot passed out during the descent, so Gay-Lussac went up again alone in September, climbing to 22,912 feet, a new altitude record which would stand for over half a century. Here, in the tradition of Dr Alexander Charles, along with his instrument readings he calmly recorded his breathlessness, fast respiration and pulse, inability to swallow and other symptoms, and concluded that he was very close to the limit of the breathable atmosphere. In the historical section of his classic book Through the Air (1873), the great American aeronaut John Wise later reflected on the courage of these early scientific ascents into the absolute unknown: ‘It is impossible not to admire the intrepid coolness with which they conducted these experiments … with the same composure and precision as if they had been quietly seated in their scientific cabinet in Paris.’ Wise also raised the prophetic possibility of using such high-altitude balloons unmanned for weather observations: ‘Balloons carrying “register” thermometers and barometers might be capable of ascending alone to altitudes between eight and twelve miles.’ But such experiments would have to wait for a time of international scientific cooperation, ‘when nations shall at last become satisfied with cultivating the arts of peace, instead of sanguinary, destructive and fruitless wars’.11

Indeed, it was the celebration balloon, used for propaganda and patriotic rather than scientific purposes, that most readily held the public’s attention in France. In December 1804 Napoleon commissioned Garnerin to construct and launch a massive, decorated but unmanned balloon to celebrate his coronation as emperor in Paris. It was festooned with silk drapes, flags and banners, and carried an enormous golden imperial crown suspended from its hoop on golden chains. Having been successfully launched above Notre Dame during the coronation ceremony, this fantastic contraption flew southwards right across France, and amazingly crossed the Alps during the night. The following day it was spotted symbolically descending upon Rome, the imperial city, a triumph for Garnerin’s craftsmanship.12

illustration credit ill.58

The huge balloon veered towards St Peter’s and the Vatican Palace, then swooped down low across the Forum. But here the symbolic triumph was turned into a propaganda disaster. The enormous golden crown became hooked on the top of an ancient Roman tomb and broke off, leaving the balloon to disappear, with its banners flapping, over the Pontine Marshes. By unbelievable coincidence, or thoroughly appropriate bad luck (you can never tell with balloons), the tomb upon which Garnerin’s prophetic balloon had deposited Napoleon’s golden crown was that of the infamous tyrant and murderous pervert, the Emperor Nero. Napoleon’s name was hooped like a deck-quoit over Nero’s.* Once this ill-starred news was efficiently relayed back to Paris by Napoleon’s diplomatic service, Garnerin and his balloons began to fall out of imperial favour.14

* Such incidents had an interesting effect on the burgeoning new genre of science fiction and fantasy. The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen (a collection of imaginary tales about an actual historical figure) was originally published in German by Rudolf Erich Raspe in 1785, though no balloons appear in this first edition. But with the series of expanded and pirated English versions between 1809 and 1895, balloon fantasies soon abounded. ‘I made a balloon of such extensive dimensions, that an account of the silk it contained would exceed all credibility,’ one tall tale begins. ‘Every mercer’s shop and weaver’s stock in London, Westminster, and Spitalfields contributed to it. With this balloon I played many tricks, such as lifting one house from its station, and placing another in its stead, without disturbing the inhabitants, who were generally asleep.’ With his massive balloon, Munchausen carries Windsor Castle to St Paul’s in London, makes the clock strike thirteen at midnight (for no particular reason), and then airlifts it back again before daylight, ‘without waking any of the inhabitants’. Later, he uses his balloon to levitate the entire building of the Royal College of Physicians. The physicians are in session (i.e. ‘feasting’), so he keeps them suspended several thousand feet in the air for ‘upwards of three months’. The consequence is that, deprived of their medical services, there are absolutely no deaths in the entire population of London, while many clergymen and undertakers go bankrupt. Munchausen adds disingenuously: ‘Notwithstanding these exploits, I should have kept my balloon, and its properties, a secret, if Montgolfier had not made the art of flying so public.’13

Garnerin was replaced, almost at once, by the most justly famous of all the French Revolutionary balloonists. She was a woman – the small, fearless and enigmatic Sophie Blanchard. Born at the sea port of La Rochelle in March 1778, Sophie somehow became involved with the experimental balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard, who had first crossed the Channel with Dr Jeffries in 1785, when Sophie was only eight. How their romance began remains a mystery, since Blanchard was already married with children, and spent much of the 1790s touring the cities of Europe and America. But it was rumoured that he first saw her when she was still a child, standing in the crowd at one of his launches, and vowed to return and marry her when she came of age in 1799.

However, the first definite record of them together is not until December 1804, when Blanchard took Sophie on her first balloon flight, above Marseille. According to him she was immediately smitten, breaking her customary painful silence to gasp, ‘Sensation incomparable!’ Pictures show her to be petite and pretty, with large eyes and a dark fringe. But she was also said to be frail and ‘bird-like’, abnormally nervous on the ground, terrified of crowds, loud noises, horses and coach travel, and shy to the point of self-effacement. Yet all this changed completely once she was in the air. In a balloon she became confident and commanding, a natural entertainer and a provoking exhibitionist, daring to the point of recklessness.

illustration credit ill.59

Blanchard, who was ageing and nearly bankrupt, evidently saw the possibilities of reviving his aeronautical career with this fearless young woman, who could instinctively control a balloon, manage aerial fireworks, do acrobatics, and wear eye-catching hats and dresses to please a crowd. He married Sophie when she was twenty-six, and she became his balloon partner for several years, taking over all the arrangements as his health gradually failed. Blanchard died from a heart attack in 1810, while landing in a damaged balloon near The Hague.15 Immediately after his death, Sophie gave her first major solo balloon display in Paris. Like Garnerin, she specialised in night ascents and firework displays, but with much greater daring and eventually recklessness. She deliberately set herself up to rival the other famous female aeronaut of the time, Garnerin’s niece Lisa. Both seemed to vie for official recognition, though Lisa suffered from the waning popularity of the Garnerin name with Napoleon.

Sophie Blanchard seems to have caught the Emperor’s attention during a midsummer ascent from the Champ de Mars in Paris on 24 June 1810. Soon after, she was asked to contribute to the celebration mounted by the Imperial Guard for Napoleon’s marriage to the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria. From then on she became a fixture at the imperial court, with propaganda as well as entertainment duties. On the birth of Napoleon’s son in March 1811, she took a balloon flight over Paris from the Champ de Mars and threw out leaflets proclaiming the happy event. She again performed at the official celebration of his baptism at the Château de Saint-Cloud on 23 June, with a spectacular firework display launched from her balloon. In the same year, in an ascent above Vincennes, she climbed so high to avoid being trapped in a hailstorm that she lost consciousness, and spent 14½ hours in the air as a result.

Napoleon now made Sophie’s position official. He appointed her Aéronaute des Fêtes Officielles, a position especially created for her, and gave her responsibility for organising ballooning displays at all major events in Paris. It was also said that he made her his ‘Chief Air Minister of Ballooning’, with secret instructions to draw up plans for an aerial invasion of England. However this seems more like English counter-propaganda, as Napoleon’s idea for an invasion of England had long since been displaced by the ultimately disastrous invasion of Russia, which began in the spring of 1812.

Sophie had by now developed her own peculiar free-style of ballooning. She abandoned her husband’s large canopy and unwieldy basket, both of which were by this time much battered. To replace them she commissioned a much smaller silk balloon, capable of lifting her on a tiny, decorative silver gondola. This was shaped like a small canoe or child’s cradle, curved upwards at each end but otherwise quite open. It was little more than three feet long and one foot high at the sides. One end was upholstered to form a small armchair (in which she sometimes slept), but otherwise the gondola offered astonishingly little protection. When she stood up, grasping the balloon ropes, the edge of the gondola did not reach above her knees. It was virtually like standing in a flying champagne bucket.

She also began to adopt distinctive outfits, which could be seen at a considerable distance. For this purpose her dresses were always white cotton and narrowly cut, with the fashionable English Regency style of high waist and low décolletage. Her sleeves were long, coming right down to her knuckles, presumably to keep her hands warm at high altitudes. Most important of all, she wore a series of white bonnets extravagantly plumed with coloured feathers, to increase her height and visibility. The combined effect of these dramatic clothes and the tiny silver gondola was to make her look both flamboyant and vulnerable. She also appeared terrifyingly exposed, an effect she evidently cultivated.

Sophie now began to give displays in Italy. In the summer of 1811 she took her balloon across the Alps by coach, and celebrated Napoleon’s birthday, the Fête de l’Empereur on 15 August, with an ascent above Milan. She travelled on to Rome with instructions to efface the memory of the unfortunate incident of Nero’s tomb. Here she ascended spectacularly to a height of twelve thousand feet, and stayed aloft all night in her tiny upholstered chair, claiming that she fell into a profound sleep, before landing much refreshed at dawn at Tagliacozzo. She then flew by balloon from Rome to Naples, splitting the journey in half with a stop after sixty miles. She made a daring ascent in bad weather over the Campo Marte in Naples to accompany the review of the troops by Napoleon’s brother-in-law Joachim Murat, the King of Naples.

illustration credit ill.60

In 1812, the third Aeronautical Exhibition was held at the Champ de Mars. With all eyes on Napoleon advancing towards Moscow, it was not a great success, so Sophie again crossed the Alps with her balloon to make ascents at Turin. On 26 April she flew so high, and the temperature dropped so low, that she suffered a nosebleed and icicles formed on her hands and face.

On her return to Paris, Sophie was surprised to receive a letter on 9 June from André-Jacques Garnerin. He gracefully invited her to dinner at the Hôtel de Colennes to discuss ‘a project that might be of mutual interest’. This probably involved a proposal to make double ascents and parachute drops above the Jardin du Tivoli or the Parc Monceau with her old rival Lisa Garnerin. It is highly unlikely that Sophie would have accepted what she must have regarded as a demeaning and unsuitable proposition.16

The defeat and subsequent exile of Napoleon seemed to pose Sophie Blanchard few problems. When the restored Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, entered Paris for his official enthronement on 4 May 1814, Sophie made a spectacular ascent from the Pont Neuf, with fireworks and Bengal lights. King Louis was so taken with her performance that he immediately dubbed her ‘Official Aeronaut of the Restoration’. Evidently Sophie had no qualms about this shift of political allegiance. Her only loyalty was to ballooning.

Four more years of brilliant public displays followed, with Sophie established as queen of the fireworks night at the Tivoli and Luxembourg Gardens. Her small balloon lifted more and more complicated pyrotechnical rigs, with long booms carrying rockets and cascades, and suspended networks of Bengal lights, all of which she would skilfully ignite with extended systems of tapers and fuses. At the height of these displays, her small white figure and feathery hat would appear like some unearthly airborne creature or apparition, suspended several hundred feet overhead in the night sky, above a sea of flaming stars and coloured smoke.

Towards midnight on 6 July 1819, a hot, overcast summer evening, Sophie Blanchard, aged forty-one, began one of her regular night ascents from the Jardin de Tivoli, accompanied by an orchestra in the bandstand below. At about five hundred feet, and still climbing, she began to touch off her rockets and Bengal lights, dropped little parachute bombs of fizzing gold and silver rain, and ignited a lattice of starshells suspended on wires twenty feet below her gondola. As the gasps and applause of the crowd floated up to her through the darkness, she became aware of a different quality of light burning above her head. Looking up, she saw that the hydrogen in the mouth of her balloon had caught fire. It was amazing that it had never done so before. Many of the crowd thought it was just part of the firework display, and continued to applaud.

The flaming balloon dropped onto the roof of number 16, rue de Provence, near the present Gare Saint-Lazare. The impact largely extinguished the fire. Sophie was not severely burnt, but she was tangled in the balloon rigging. She slid down the roof and caught onto the parapet above the street. Here she hung for a moment, according to eyewitnesses, calmly calling out ‘A moi, à moi!’ Then she fell onto the stone cobbles beneath.

There are numerous accounts of this fiery descent from the Paris sky. They appeared in all the Paris newspapers, and also in English journals like the Gentleman’s Magazine.17 One of the clearest, most poignant descriptions was written by an English tourist, John Poole, who witnessed the event from his hotel room.

I was one of the thousands who saw (and I heard it too) the destruction of Madame Blanchard. On the evening of 6 July 1819, she ascended in a balloon from the Tivoli Garden at Paris. At a certain elevation she was to discharge some fireworks which were attached to her car. From my own windows I saw the ascent. For a few minutes the balloon was concealed by clouds. Presently it reappeared, and there was seen a momentary sheet of flame. There was a dreadful pause. In a few seconds, the poor creature, enveloped and entangled in the netting of her machine, fell with a frightful crash upon the slanting roof of a house in the Rue de Provence (not a hundred yards from where I was standing), and thence into the street, and Madame Blanchard was taken up a shattered corpse!18

The death of the Royal Aeronaut profoundly changed the reputation of ballooning in France. A public subscription was raised in her honour, but it was found that Sophie Blanchard had no family, and was reported to have left fifty francs in her will ‘to the eight-year-old daughter of one of her friends’ (perhaps an illegitimate child?). So the two thousand francs raised was used to erect a notable balloon monument, which still exists in the 94th Division of Père Lachaise cemetery.*

illustration credit ill.61

illustration credit ill.62

* The mysterious, ‘bird-like’ Sophie Blanchard has attracted more romancing than any other female aeronaut. She is the subject of a novel by Linda Doon, The Little Balloonists (2006), in which she enchants Goethe and actually seduces Napoleon. She is also celebrated, like a local saint, at an annual event in the little Italian Alpine town of Montebruno, where she once landed in her balloon. She has become adopted as a feminist heroine, ‘the first professional female aeronaut’, and the film-maker Jen Sachs is making an animated cartoon of her life, The Fantastic Flights of Sophie Blanchard.

Sophie Blanchard’s death in 1819 effectively ended the first great wave of ballomania and the celebration of ballooning in France. Something similar happened in England with the equally shocking death of Thomas Harris five years later. Amazingly, Harris was the first English aeronaut to be killed on home ground. A glamorous young naval officer, he made a much-advertised ascent in his new balloon the Royal George on 24 May 1824. As part of his publicity, he took with him a dazzlingly pretty eighteen-year-old cockney girl, known to the newspapers only as ‘Miss Stocks’, who was generally assumed to be his mistress. Miss Stocks and the balloon, which had cost Harris a thousand guineas to construct, had both been exhibited at the Royal Tennis Court in Great Windmill Street, and stirred much excitement and comment.19

The balloon had a new kind of duplex release valve, which Harris said would allow him and Miss Stocks to make a perfectly controlled landing. One valve was housed inside the other at the top of the balloon. The smaller, inner valve was the conventional safety mechanism, as invented forty years previously by Alexander Charles, designed to release excess gas pressure during flight, or to commence a controlled descent. The larger outer valve was a radical solution to the problem of keeping the balloon safely on the ground once it had landed. When the larger valve line was pulled, it would deflate the entire balloon in a matter of seconds (the equivalent of the ‘rip panel’ in a modern hot-air balloon). This, claimed Harris, would prevent the terrible bouncing and dragging across fields which had caused so many injuries, and so much damage to crops and property (especially chimneys and rooftops) which had undermined the general popularity of balloonists.

Harris circulated a campaigning pamphlet saying that he was trying to save the declining art of ballooning in England. ‘The Science of Aerostation has lately fallen into decay, and has become the subject of Ridicule,’ he lamented. This decline was caused by the ‘total want’ of serious technical inventions by recent aeronauts, who had been content (like that Frenchman Garnerin) to exploit frivolous novelties like parachutes and fireworks. The Royal George, with its new system of valves and its beautiful young passenger, would show the way ahead. In the event it showed something quite else.

Harris took his balloon and Miss Stocks from the West End to the East End to generate further interest, and launched successfully from the large courtyard of the popular Eagle Tavern, in City Road. It was noted that Lieutenant Harris wore his best blue naval uniform, and Miss Stocks a charming dress, much as if they were a honeymoon couple, which perhaps they were. The change in venue was probably made because the wind was blowing south-westwards that day. It took the balloon back across London and the river Thames, an excellent display route, and then on into Kent and towards Croydon. All went well in the basket, champagne was drunk, and Harris then attempted his first perfect display landing at Dobbins Hill, just outside Croydon. However, this did not quite go to plan.

Distracted either by Miss Stocks or by his new duplex valve, he forgot to hang out his grapnel line in time, and was forced to throw out ballast to avoid colliding with some nearby trees. This was by no means a disastrous error, but it evidently rather flustered Harris. The balloon rose several hundred feet in the air, and was carried on over Beddington Park, on the other side of Croydon. Here Harris evidently prepared for a second attempt at a landing.

The swift sequence of events that followed has remained a matter of dispute ever since. For no accountable reason, the Royal George suddenly began to descend from several hundred feet ‘with fearful velocity’. As it dropped, it was claimed by witnesses that some kind of struggle was briefly observed in the basket. The partially deflated balloon plummeted ‘with frightful rapidity’ into a large oak tree in the park, tore through the light spring foliage (it was only May) and dashed its passengers to the ground. ‘They were shortly afterwards discovered, buried beneath a monumental pile of silk and network.’ Both of them were outside the basket, but while Thomas Harris was dead, Miss Stocks was alive and conscious, though quite unable to give a coherent account of what had occurred during the last few seconds.

What had destroyed the balloon seemed obvious to the coroner. The new large gas valve – ‘the preposterous aperture’ – had been released prematurely. The coroner ascribed this to Harris’s fatal error in pulling the wrong valve line while still in the air. Later aeronauts, like Charles Green, analysed the sequence of events more subtly. Green suggested that Harris’s only error was to have tied the larger valve line to a point in the basket, precisely to keep it safe and out of the way, especially with Miss Stocks aboard. However it had pulled itself taut – ‘a longitudinal extension of the apparatus’ – when the balloon contracted, thereby unexpectedly and fatally releasing the deflation valve by itself. This was a kindly, if ingenuous, explanation, which did not quite square with the evidence that Miss Stocks gave afterwards: ‘Miss Stocks declares that she distinctly heard the peculiar sound which always accompanies the shutting of the valve, as soon as Mr Harris had let go the line.’ This sounds as if Harris had indeed pulled the line himself, and realising his error, had let it go too late. But of course, Miss Stocks could have meant ‘as soon as Mr Harris had untied the line’.20

The much larger question, and the one that made ‘le mort de Harris’ a cause célèbre in France, was a more human mystery. Why did Miss Stocks survive when Lieutenant Harris died? The disposition of the bodies gave little clue, both presumably having been thrown from the basket on impact. But the suggestion almost inevitably arose that the gallant Harris had somehow saved the beautiful Miss Stocks.

British commentators were brusque about this mystery ‘that has hitherto clouded the event’, and gave romantic explanations short shrift. Most probably, a branch of the oak tree, ‘projecting horizontally’, had protected Miss Stocks (though unfortunately not Harris). Just possibly Miss Stocks ‘had fainted, and fallen forward … upon the body of Mr Harris’. Thereby he had unintentionally protected her from ‘the first violence’ of the impact. Anything else pandered to ‘false and scurrilous reports’.21

French journalists were more liberal in their interpretations. Lieutenant Harris and Miss Stocks could have been distracted ‘in many ways’, so that the wrong valve line was pulled. Lieutenant Harris would surely have tried to protect Miss Stocks with his body during the terrifying descent, ‘if not before’. But most likely of all, and the real reason for her survival, was that Lieutenant Harris ‘in a spirit of admirable chivalry’ had leapt from the balloon basket before the moment of impact, in a quixotic attempt to reduce the speed of her fall.22 It was a gesture of true English gallantry from a true English naval officer. The romantic image of Lieutenant Harris leaping from the balloon to save his beloved became an iconic one in France, and featured alongside images of the death of Pilâtre de Rozier and Sophie Blanchard in a famous series of French balloon cards. They marked the end of an era.

illustration credit ill.63

The growing scepticism about the future of ballooning was summed up by the satirical artist George Cruikshank. In his brilliant coloured cartoon of 1825 entitled ‘Balloon Projects’, he depicted a row of gaudily striped balloons tethered down the length of St James’s, like a rank of hackney cabs waiting for hire. A fashionable couple are about to climb gingerly into one of them (with pink plush upholstery), to embark on a ‘one shilling’ flight from Mayfair to the City. Each balloon car is manned by a suitably villainous driver, one of whom is shouting to another, ‘I say, Tom, give my balloon a feed o’ gas, will you!’

Above them the sky is filled with a mass of grotesquely shaped balloons, one in the form of a hogshead of beer, another with a weathercock on top, and a third on fire with its passengers leaping out. Behind them all the buildings are advertising balloon companies and businesses, which is probably the real point of Cruikshank’s satire. These dubious establishments include ‘The Balloon Life Assurance Company’, ‘The Bubble Office’, ‘The Office of the Honourable Company of Moon Rakers’, and perhaps most ingeniously, ‘The Balloon Eating House – Bubble & Squeak Every Day’.23

illustration credit ill.64

The historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, friend of John Keats and Charles Lamb, who kept a close if disillusioned eye on London freaks and fashions from his studio near Baker Street, noted grimly in his diary for 6 June 1825: ‘No man can have a just estimation of the insignificance of his species, unless he has been up in an air-balloon.’

Of course, not everyone was so disillusioned. A remarkable balloon is featured in Jane Loudon’s extraordinary science fiction novel The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-First Century (1827). It was written when Loudon was aged twenty, ‘a strange, wild novel’, as she herself called it, full of totally unexpected technical inventions, such as ‘steam percussion bridges’, heated streets, mobile homes on rails, smokeless chemical fuels, electric hats (for ladies), and most spectacularly a full-size balloon made from a nugget of highly concentrated Indiarubber. Small enough to be stored in a desk drawer, such a ‘portable’ balloon once inflated is large enough carry three people from Britain to Egypt.24

Loudon’s description of an aerial balloon carnival is brilliantly prophetic of modern balloon fiestas, especially the more psychedelic American ones: ‘The air was thronged with balloons, and the crowd increased at every moment. These aerial machines, loaded with spectators till they were in danger of breaking down, glittered in the sun, and presented every possible variety of shape and colour. In fact, every balloon in London or the vicinity had been put into requisition, and enormous sums paid, in some cases, merely for the privilege of hanging to the cords which attached to the cars, whilst the innumerable multitudes that thus loaded the air, amused themselves by scattering flowers upon the heads of those who rode beneath.’ The fantastic balloon shapes include, for more sportive individuals, ‘aerial horses, inflated with inflammable gas’, and for the more languid, ‘aerial sledges’ which can be flown from a supine position.25