On 15 April 1861 the newly elected President Abraham Lincoln declared an ‘insurrection’ in America’s Southern states, and sent out a call for seventy-five thousand troops to volunteer – but only for a brief three-month period.1 His aim was rapidly to crush what was then seen as a local and ill-organised farmers’ ‘rebellion’ in the deep South, largely in the six cotton-growing slave states – South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana – which had formed a loose armed Confederacy. The ‘rebellion’ was initially a scattered and desultory affair, having begun with the storming of Fort Sumpter in Charleston harbour, South Carolina. But the seceding states, joined by Texas, soon founded a new Southern capital in distant, rural Montgomery, Alabama, over a thousand miles from Washington, and brazenly elected a new Congress there.

With a huge preponderance of men, weaponry and industrial materials, the North or Union appeared to have an unassailable advantage, and intended to bring the South to heel with a brief and punishing blockade. However, by the end of May, four more slave states – Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina and part of Virginia – had joined the Confederacy. Moreover, several brilliant generals had rallied to its ranks: notably Robert E. Lee and ‘Stonewall’ Jackson – and the spirit of Southern patriotism, the spirit of ‘Dixie’, had caught light. With startling confidence the rebels dashingly moved their capital north from Alabama to Richmond, Virginia, a mere ninety-eight miles from Washington, and soon had some two hundred thousand troops in the field.2 They also repudiated the anti-slavery rhetoric of the North, and began to create the powerful mythology of a graceful, productive, agrarian South, shamefully set upon by a brutal, bullying, mechanised North. In a curious way, balloons would eventually contribute to both sides of this propaganda warfare. From then on the conflict escalated into a full-blown civil war, which would endure for four long and terrible years. By the end, Lincoln would have been forced to raise over a million troops.

The rebels’ provocative initiative in occupying Richmond in April 1861 effectively dictated the first eighteen months of the conflict. Other early campaigns were fought in Missouri, the Shenandoah Valley, and distant Tennessee; and the rebel city of New Orleans in Louisiana fell in April 1862.3 But for the Union the early watchword became ‘On to Richmond!’ In consequence, most of the early fighting was restricted to the state of Virginia, stretching between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean.

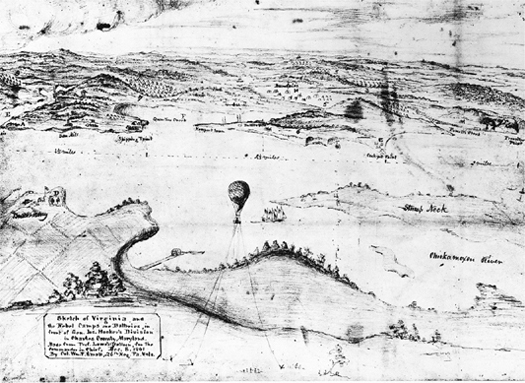

It was an area divided by four great rivers running south-eastwards (like the fingers of a spread hand) into Chesapeake Bay – the Potomac, the Rappahannock, the York and the James. Moving between these, the conflict was highly mobile and violent, yet strangely indecisive. It involved a series of back-and-forth manoeuvrings, alternately to subdue or to defend the rebel stronghold. The campaign opened with the First Battle of Bull Run, just west of Washington, in July 1861, and ended with the Seven Days Battle just north of Richmond in July 1862.4

Balloons were present at most of these bloody encounters, and especially in the latter phase, fought along the narrow strip of land between the James and the York rivers, known as the Virginia Peninsula. Balloon operations were restricted, even marginal, but in some cases were crucial in supplying military intelligence. Yet their value was always disputed. Remarkably, they played virtually no part in the war after the Battle of Fredericksburg (on the Rappahannock river) in December 1862.5 But for the aeronauts, all Atlantic schemes were hastily put aside from April 1861 onwards. Instead, the great rivalry between Lowe, Wise and LaMountain shifted to the struggle to become appointed as the official aeronaut of the Union army. In this endeavour, patriotism, rather than profit, seems genuinely to have motivated them.6

Lowe had already experienced the growing ill-feeling between North and South at first hand. On 19 April 1861, just as the drums of war had begun to sound in Washington, he had launched his small, businesslike balloon the Enterprise from a vacant lot in the heart of Cincinnati. This flight had originally been conceived, on Professor’s Henry advice, as a scientific investigation of the easterly air current, but at some point it had become a demonstrative effort to impress the Union government.

Click here to view larger image

Accordingly, Lowe’s ambitious plan was to fly five hundred miles due eastwards over the Allegheny Mountains, and to land in Washington, ideally perhaps on the front lawn of Lincoln’s White House. Here he might offer his services to the Union cause, and outflank his rival aeronauts. In the event he met a rebel breeze, and ended up much further south, having skirted Kentucky and Tennessee, and finally touching down near Unionville in the heart of the seceded state of South Carolina. Nevertheless, he had flown 650 miles solo in just over nine hours, a feat that compares well with the Wise–LaMountain flight of 1859.7

On landing, Lowe found the Civil War already declared and decidedly in progress. The local cotton farmers were not impressed by his flying skills or his Yankee accent. On the contrary, he was arrested as a spy for supposedly carrying despatches from the Union North, blatantly piled in the corner of his balloon basket. With some difficulty, due to local illiteracy, he was able to demonstrate that these despatches were actually a special balloon edition of the Cincinnati Daily Commerce, and thereby escape being lynched.8

The Enterprise having been extricated undamaged, Lowe and his balloon were packed off unceremoniously on a coach back westwards. Once safe in Kentucky, which had not seceded to the South, he switched to the railroad and hurried north to Washington, with his balloon and basket in packing cases. Here the news was that the Union Army of the Potomac was preparing to invade rebel Virginia, and was already skirmishing across the Potomac river near Arlington. Its new commander, General George C. McClellan, like a good Yankee, was in principle sympathetic to advanced technology. Lowe consulted with Professor Henry at the Smithsonian, and came up with a revolutionary new idea. Provided it was securely tethered, the Enterprise could carry up telegraph equipment and a wire, and send direct aerial observations to a commander on the ground. He demanded to demonstrate this to President Lincoln himself as a matter of acute urgency.

It says a great deal about Lowe that, amidst all the administrative chaos of a newly declared war, he achieved exactly this. On Sunday, 16 June 1861, Lowe ascended in his balloon some five hundred feet above Constitution Mall, Washington, with a telegraph key and an enthusiastic Morse operator. The telegraph wire was strapped to the tether line and winch, and then run directly across the lawn and into a service room in the White House. Lowe transmitted the following message:

Balloon Enterprise. Washington, D.C. 16 June 1861

To President United States:

This point of observation commands an area nearly fifty miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station and in acknowledging indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the service of the country. T.S.C. Lowe9

This historic message was seen by Lincoln himself, who called Lowe in for discussions that same evening. On 21 June Professor Henry, having observed the demonstration from the roof of the red-brick Smithsonian building on the other side of the Mall, wrote a decisive letter of support to Lincoln’s Secretary for War, Simon Cameron: ‘From experiments made here by Professor Lowe, for the first time in history, it is conclusively proved that telegrams can be sent with ease and certainty between the balloon and the headquarters of the Commanding Officer.’10

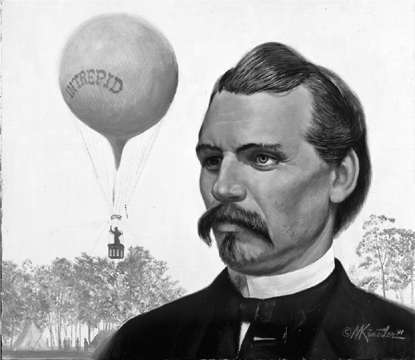

In this dramatic fashion Lowe succeeded in persuading Lincoln to allow him to form an official Military Aeronautics Corps within the Union army. But administrative things moved slowly. A month later, on 21 July, Lincoln had to write a second order in his own hand urging that ‘Professor Lowe and his balloon’ should receive the fullest cooperation from General Winfield Scott, the slow-moving C-in-C of the Union forces.11 In August the Aeronautics Corps was finally placed under the direct control of General George McClellan, the much younger and more dynamic commander of the Army of the Potomac, who was soon to command the entire Union army in the Virginia theatre. McClellan quickly became one of Lowe’s warmest supporters, and would make his first balloon ascent with Lowe on 7 September 1861. He believed that balloon observation would be vital to the new, highly mobile form of infantry warfare.

Lowe had finally received Union funds to build further balloons in August 1861. His fleet eventually consisted of no fewer than eight military aerostats: the Union, the Intrepid, the Constitution, the United States, the Washington, the Eagle, the Excelsior, and the original Enterprise. The new balloons were small and functional, ranging in size from fifteen thousand to thirty-two thousand cubic feet, though each could carry enough tether and telegraph cable to climb to five thousand feet.

To save weight, their observation baskets were unbelievably small, not much bigger than modern tea-chests, approximately two feet square and two feet deep. For a man sitting, the sides would barely reach to his armpits; for a man standing, they would not even reach to his knees. By way of reassurance, they were painted on the outside with the Union stars and stripes on a white background; though it was said that this provided a better target for Confederate sharpshooters to take a bead on. Only the fearless Sophie Blanchard had ever flown in baskets as small as this. But then, she had never been fired at while doing so.

The first balloon designed specifically for military use, the Union, was ready for action on 28 August 1861. On 24 September, Lowe ascended in it to more than a thousand feet near Arlington, across the Potomac River from Washington, and began telegraphing intelligence on the Confederate troops located at Falls Church, Virginia, more than three miles away. Union guns were then calibrated and fired accurately on these enemy dispositions without actually being able to see them. This was an ominous first in the history of warfare, by which destruction could be delivered to a distant and invisible enemy.

illustration credit ill.90

illustration credit ill.91

Meanwhile, rival aeronaut John LaMountain was also attempting to provide balloon services for the Union. He too wrote to Lincoln in spring 1861, but having no influential backers like Professor Henry, he did not receive a reply. However, from July 1861, using his heavily repaired and battered balloon Atlantic (still financed by the faithful Oliver Gager), he made several reckless demonstration ascents at Fort Monroe, on the strategic southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula. These were at the invitation of the local Union commander, General Benjamin Butler, and provided information on the Confederate troops massed along the James River. Though employed as a civilian, and not officially belonging to the Army of the Potomac, LaMountain could claim to have made the first aerial reconnaissance of the Civil War.12

The remarkable thing about these ascents is that many were free flights, without tether ropes or telegraph cables, and made directly over enemy lines. LaMountain eloquently explained why he took such risks:

Typical ascensions, with balloon attached to the earth by cords, do not allow the attainment of an altitude sufficient to expose a considerable view … To the eye of the [free] aeronaut, who can by knowledge of his art … sail directly over points impenetrable by pickets or scouts, secrets of the most important character are clearly revealed. The country lies spread before him like a well-made map, with all its varieties of hill and valley, river and defile, distinctly defined, and every fort, encampment, or rifle-pit within range of many miles, manifest to observation.13

The flamboyant style of the aeronautical ‘art’ employed by LaMountain was typical of him. Irascible and arrogant he may have been, but no one could doubt his skill and impetuous courage. On several occasions he took his balloon at low level right across the Confederate lines at Hampton on the James River, and later at Alexandria on the Potomac, sowing dismay and fury among the enemy troops, who shouted and shot at him, but without effect. The Confederates thought he was doomed to come down behind their own lines, where he would undoubtedly be captured and summarily shot as a spy.

But at this point, LaMountain would drop ballast and soar up to eight thousand feet.14 Here he entered, as he knew he would (or at least certainly hoped he would), the top layer of an air ‘box’. This is a fixed air pattern – fixed, at any rate, at certain seasons and times of day – in which the upper current is exactly reversed in direction from the lower.* So LaMountain sailed mockingly back over the entire Confederate army, and, valving fast, brought the Atlantic safely back virtually to its point of departure in the Union rearguard, and delivered his report.

On at least one occasion he was nearly shot by a German brigade of Union troops as he landed, an early example of ‘friendly fire’. ‘An infuriated crowd of officers and men were intent on destroying the balloon and myself … One bullet passed rather unpleasantly close to my head,’ as he remarked laconically. These flights, both free and tethered, caused a sensation among the opposing armies. The Scientific American remarked on LaMountain’s reckless courage, and the New York Times reported that he had been able to view the whole Confederate encampment right up the east side of the James River, and later all the rebel manoeuvrings on the west side of the Potomac. A new era in aerial observation had begun.15

However, LaMountain’s spectacular showmanship was not designed to impress the cautious senior officers of the Union army. Ironically, it might have gone down better with inspirational and inventive Confederate generals like Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. Unlike the well-organised and well-connected Lowe, he had difficulty in obtaining funds for further equipment. He did finally manage to lay his hands on another balloon, the Saratoga, but this was almost immediately lost through his own recklessness on 16 November 1861. He then tried to requisition one of Lowe’s balloons from the Aeronautics Corps, but Lowe refused to cooperate, describing him bluntly as a man ‘known to be unscrupulous and prompted by jealousy’. This antipathy was probably mutual. Each man found supporters in Washington, and the rivalry between the two grew. Finally, after further accusations and hostilities on both sides, in February 1862 General McClellan dismissed ‘Professor’ LaMountain from any further service to the Union military.16

* The air ‘box’ is still used by modern hot-air balloonists. There is, for example, a famous north–south ‘box’ above Albuquerque, New Mexico, which is used to stunning effect during the famous mass ascents at the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta. I have taken off at dawn with three hundred other balloons flying south, and then an hour later, after modestly landing on a downtown baseball field, looked up to see fleets of balloons thousands of feet overhead, steadily returning to their birthplace like some miraculous airborne shoal of glinting salmon returning to their original spawning grounds. The effect of a balloon successfully returning to its launch point after a flight of several hours, a thing that should be logically impossible, is curiously moving and heartwarming. If I were American, I would say it was like your favourite baseball team scoring a home run.

For the rest of 1862 it was Lowe’s Union Balloon Corps which operated exclusively during the Virginia phase of the Civil War. McClellan’s basic strategy was to assault the rebel capital with a pincer movement. His plan was to transport the Army of the Potomac down to Fort Monroe, and then steadily roll back the Confederate forces up the ninety-mile length of the Virginia Peninsula – through Hampton, Yorktown and Williamsburg – until Richmond could be encircled from the south. Meanwhile he would drive other scattered rebel elements back down the west bank of the Potomac, and approach Richmond from the north.

The small but incredibly fierce battles which now took place between the York and the James rivers came to be known as the Peninsula Campaign. Lincoln’s hope was that it would result in a short war. But throughout 1862 McClellan’s Army of the Potomac constantly threatened, but did not actually manage to take, the vital and symbolic rebel stronghold. In the end there was no short war. Richmond did not finally fall until April 1865, precipitating Lee’s historic surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House (and the great culminating chapter of Gone with the Wind).

Lowe’s balloons were present at the siege of Yorktown in May 1862; at the Battle of Fair Oaks in May–June 1862; at the crucial Seven Days Battle outside Richmond in June–July 1862; and at the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. He also witnessed the famous rebel victory by Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville in May 1863. The last telegraph message Lowe sent from a balloon during the Civil War was from Chancellorsville. It was time-dated 10.45 a.m. on 5 May 1863, and foretold the rebel victory: ‘I am unable at this time to see a movement of the enemy except some wagons moving up and down the river. The enemy in force appears to hold all the ground they gained yesterday.’17

illustration credit ill.92

From his balloons, Lowe witnessed a new kind of American fighting. Rapid, violent, passionate and patriotic (on both sides), it was based on a swift exchange of attack and counter-attack. There were long days of immobility and siege, especially at Yorktown. But most characteristic was the constant manoeuvring of infantry and artillery across open countryside chequered with small townships, manufactories, farmsteads, mills, river bridges and railway junctions, any one of which could suddenly become a strategic key point, where thousands might die. Speed, and often dissimulation, were vital factors. Military intelligence – the knowledge of the enemy’s dispositions, troop numbers, firepower, potential reinforcements, and above all its unexpected movements and hidden intentions – was paramount. Lowe always believed that balloons could supply this.

Lowe’s observations during these early months also provided the first terrible evidence of the nature of this modern battlefield, and the new weaponry deployed upon it. He saw the long-distance impact of heavy artillery shells from the twelve- and sixty-four-pounder field guns; the effect of mines and the new-style hand grenades; the devastation of exploding canister shells on an infantry advance; and the terrible skittling effect of a volley of Springfield rifles fired at two hundred yards. The Springfield fired a big 0.58-calibre bullet capable of blowing off an entire limb at a thousand yards.18

He also saw the cruel deceptions increasingly practised with the new equipment. One of his telegraph officers, having bravely climbed a telegraph pole under fire to fix a broken line, climbed down and stepped directly onto a ‘torpedo’ or anti-personnel mine that had been buried at the foot of the pole by the retreating Confederates. It blew the man in half.

What Lowe observed was a new kind of infantry war, with great tides of men and metal constantly clashing. It produced casualty figures never before seen in American history. At Bull Run (July 1861) five thousand dead and wounded; at Fredericksburg (December 1862) seventeen thousand dead and wounded; at Chancellorsville (May 1863) thirty thousand dead and wounded; at Gettysburg (July 1863) nearly fifty thousand dead and wounded.

Yet Lowe rarely described the human details of what he saw.* Instead, he confined himself to tactical reporting, like someone observing the moves in a vast, impersonal game of chess. But the unmistakable sounds of war came up to him – the boom of shells, the rattle of shots, the screaming of wounded. He wrote: ‘It was one of the greatest strains upon my nerves that I ever have experienced, to observe for many hours a fierce battle.’20

Lowe was always active and adaptable. His balloons were brought into action from horse-drawn carts, from railroad wagons, and even from the decks of boats. At one stage he operated a tethered observation balloon from a coal barge, the Rotary, sailing up and down the Potomac River. He afterwards claimed it was the first ‘aircraft carrier’ – although his rival LaMountain had done the same thing on the James River. He was prepared to inflate his balloons from coal-gas mains, hydrogen field-generators, or cobbled-together barrels of sulphuric acid and metal shell-casings. On one emergency occasion he even used another balloon, ‘transfusing’ the gas from his small Constitution via a makeshift valve (‘contrived from a convenient kettle’) into the larger Intrepid.

Lowe himself had no doubts as to the impact of his Balloon Corps in the early months of the Peninsula Campaign. As he put it graphically: ‘A hawk hovering above a chicken yard could not have caused more commotion than did my balloons when they appeared before Yorktown.’21 Rebel sources seemed to agree: ‘At Yorktown, when almost daily ascensions were made, our camp, batteries, field works and all defences were plain to the vision of the occupants of the balloons … The balloon ascensions excited us more than all the outpost attacks …’22

illustration credit ill.93

All Lowe’s observation were made from tethered balloons. Except, that is, on one memorable occasion involving the unfortunate Lieutenant-General Fitzjohn Porter, whose balloon broke from its cable, ‘and kept right on, over sharp shooters, rifle pits, and outworks, and finally passed, as if to deliver up its freight, directly over the rebel heights of Yorktown’. But miraculously it returned, having encountered a LaMountain-style air box, and crashed down onto some Union tents. Porter emerged from the heap of canvas, still brandishing his telescope, and was immediately serenaded by a nearby military band. It is not recorded what tune they played him.23

Lowe’s field units typically consisted of two hydrogen gas generators and two balloon equipment carts (winches, cables, envelopes), pulled by a team of eight horses and manned by a detachment of fifty non-commissioned soldiers. There was also a field telegraph unit, and a team of runners.24 He had two basic methods of observation, depending on wind strength and direction. In fine weather he would fly directly above the enemy positions, at an altitude between one and two thousand feet, acting like a true ‘spy in the sky’. In bad weather or contrary winds, he would fly on double tethers at five hundred feet above his own positions, where he functioned more like a traditional lookout on an aerial platform. In both cases he was regularly shot at, though remarkably none of his balloons was ever brought down. But the lower platform position was particularly unpopular with his detachment, as the moment the balloon was seen rising above the trees, Confederate field-gunners would immediately try to shell its estimated ground position.25

Military observation with binoculars was a delicate art. A tethered balloon was rarely stable – at five hundred feet in any kind of wind Lowe found the balloon ‘very unsteady, so much so that it was difficult to fix my sight on any particular object’. At a thousand feet he could see twelve miles and a whole battlefield, yet always ‘indistinctly’ because of the dust, smoke and heat haze produced by masses of troops on the move. Even more, the heavy silver-grey smoke produced by field guns in action might temporarily block out the ground altogether.26 †

Lowe communicated his observations by various means. Ideally, he used a telegraph key operated from his balloon basket, transmitting messages down a five-thousand-foot telegraph cable directly to McClellan’s headquarters. But bad conditions often made this impossible – the equipment could be too heavy to take aloft, or the cable could break. In that case, Lowe would make notes and drop them in canisters to a telegraph operator on the ground. He did the same with rapidly drawn sketch maps of the enemy positions, which were then delivered to McClellan by runner. On other occasions he used signal flags, coloured flares or simply hand-gestures. If all else failed, he would have himself winched down so he could deliver his observations in person, sometimes galloping to the headquarters on his favourite grey mare, a procedure he apparently enjoyed.

illustration credit ill.94

Many of his most urgent observations consist of three or four short lines, obviously scrawled in haste, but carefully time-dated down to the nearest minute.27 While observing the battle for Richmond from the Intrepid, he noted: ‘I immediately took a high altitude observation as rapidly as possible, wrote my most important dispatch to the commanding general on my way down, and I dictated it to my expert telegraph officer. Then with the telegraph cable and instruments, I ascended to the height desired and remained there almost constantly during the battle, keeping the wires hot with information.’28

Lowe had promised to supply McClellan with strategic aerial photographs, which he said could be examined by giant magnifying glasses once delivered to the ground. He claimed optimistically that a three-inch-square glass negative would provide the equivalent of a ‘20 foot panoramic image’ of a battlefield. He took aloft several professional photographers – ‘[Matthew] Brady the celebrated War photographer was also much interested in the work of the Corps, and spent much time with us’29 – and the British balloonist Henry Coxwell also reported that ‘some photographs were taken of the [Confederates’] position’.30 Yet no such aerial photographs have survived. While there are thousands of Civil War photographs taken on the ground, there is not a single known photograph of a Civil War battlefield taken from a balloon.31 Probably cameras, glass negatives and chemical developing equipment proved too cumbersome for the tiny observation baskets. Or perhaps the whole process was simply too slow to be of any practical use. In the event, the mysteries of early balloon photography would be explored in Paris.

illustration credit ill.95

Timing was vital, because what Lowe had discovered was the highly mobile nature of battlefield observation. This transformed the traditional idea of the tranquil, all-seeing ‘angel’s-eye view’ from a balloon. In warfare, the panoptic vision no longer provided the classic, unfolding ‘map’ of the world beneath (an image still used by LaMountain). Instead it revealed a constantly moving game-pattern, a shifting topography of hints and clues, secrets and disguises, threats and opportunities. An entire tactical situation could change within a matter of hours, or even minutes.

Visual clues had to be carefully sought out: smoke from campfires, rising road dust, sun glinting on armoury, newly dug patches of raw earth, the straight lines of fresh infantry trenches, the faint dimpled shadows of breastworks, the regular white circles of bell tents, the deep curving tracks left by heavy guns. Lowe writes on one occasion of taking a General ‘to an altitude that enabled us to look into the windows of the city of Richmond’. The battle landscape had to be read constantly, interpreted shrewdly, and summarised with the utmost speed.32

One of Lowe’s most brilliant observational coups was the discovery of the Confederates’ secret evacuation of Yorktown, under the cover of darkness, on the night of 4–5 May 1862. This gave the Union army one of its most crucial tactical advantages in the whole Peninsula Campaign. At the time it was thought that Yorktown was being resupplied, and stiffening its defences against the Union’s long siege. Lowe’s account is vivid, and turns on a single, precisely observed detail. First of all he sets the scene: ‘The entire great fortress was ablaze with bonfires, and the greatest activity prevailed, which was not visible except from the balloon. At first the General [Heintzelman] was puzzled on seeing more wagons entering the forts than were going out.’

This was apparently clear evidence of resupplying. Lowe, however, observed and interpreted more carefully: ‘But when I called his attention to the fact that the ingoing wagons were light and moved rapidly (the wheels being visible as they passed each campfire), while the outgoing wagons were heavily loaded and moved slowly, there was no longer any doubt as to the object of the Confederates. They were withdrawing.’

According to Lowe, his observations of this secret evacuation carried instant conviction to the highest command level: ‘General Heintzelman then accompanied me to General McClellan’s headquarters for a consultation, while I with the orderlies, aroused other quietly sleeping corps commanders in time to put our whole army in motion in the very early hours of the morning, so that we were enabled to overtake the Confederate army at Williamsburg.’33 The result was one of the few decisive victories of the Union Army of the Potomac, which was otherwise becoming characterised by its lack of decision and initiative. By the end of May McClellan was within five miles of Richmond.34

* Some things about the Civil War battlefields were peculiarly invisible from a balloon. For example, that more than half of all the ordinary, non-commissioned troopers were boys under seventeen; and that nearly two-thirds of all casualties of whatever rank were caused by disease – especially acute diarrhoea – not by battlefield wounds. Perhaps least visible of all was the fate of the black troops who fought so heroically for the Union. Of more than twenty-seven thousand deaths among these black soldiers, fewer than three thousand perished in combat – the rest died from disease, their conditions were so bad. Balloon observers also had little to report about the great question that had triggered the Secession: black slavery. Their occasionally flippant attitude to what they might have seen was caught in a facetious article that appeared at the home town of ballooning, in the Cincinnati Gazette for 22 October 1861: ‘LaMountain has been sent up in his balloon, and went so high that he could see all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, and observe what [the Confederate troops] had for dinner at Fort Pickens, Florida … A reporter asked him if he could see any Negro insurrections, and he said that he did see some black spots moving around near South Carolina, but found out afterwards that they were some ants which had got into his telescope.’19 It is instructive that Cincinnati was a Union city, of apparently solid anti-slavery sentiment.

† I was amazed to find Thaddeus Lowe’s long, grey gunmetal observation binoculars, much battered from use, at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, DC. They have been placed, with brilliant appropriateness, in a solitary plain glass cabinet at the foot of an exhibition of modern observation satellites, dating from the 1960s. The astonishing images taken from these orbiting space satellites, some military but most civilian, suggest that they are the ultimate heirs to Lowe’s observation balloons. The dazzling photographs of the earth beneath, breathtaking in their detail and formal patterning, are surely what Lowe must have dreamed of seeing one day from his tiny, swaying, perilous platform.

One of Lowe’s innovations was to take journalists up with him in the basket, knowing what brilliant newspaper copy he could provide. Frank Leslie, a pioneer of American illustrated magazines, paid for one of his best war artists, Arthur Lumley, to go up in Lowe’s balloon and draw battlefield pictures.35 George Townsend of the Philadelphia Inquirer, an old friend from the City of New York days, was taken on an unexpected night ascent. His article begins with a romantic touch: ‘Said the Professor: “Will you make an ascension with me tonight?” “Where to?” I answered, greatly astonished as to the meaning of the Professor’s enquiry, “To the moon?” ’

But soon Townsend was noting the bitterly cold air, the disturbing clarity of the stars, and the soldiers’ campfires below like ‘a handful of glowing embers’. Most disquieting was the silence, interrupted only by the unnerving ‘grate’ of the netting against the sides of the balloon, and the ‘collapsing and expansion of the silk’, like some enormous creature breathing, and ‘highly suggestive of a break’ somewhere unseen in the canopy. Though not a single shot was fired all the time they were airborne, it was an extraordinarily tense and disturbing experience.36

By contrast, an unnamed British reporter for the St James’s Magazine in London, largely ignoring tactical matters, was delighted to turn in a sensational, all-action scoop, which he entitled ‘Three Months with the balloons in America’: ‘The Confederates fire on the balloon and the first shell passes a little to the left, exploding in a ploughed field. The next, to the right, burst in mid-air. The third explosion is so close that the pieces of shell seem driven across my face, and my ears quiver with the sound …’37

A military correspondent for the London Times, Lieutenant George Grover, reported more soberly from the later battlefield of Chickahominy: ‘During the whole of the engagement, Professor’s Lowe’s balloon hovered over the Federal lines at an altitude of two thousand feet, and maintained successful telegraphic communication with General McClellan’s headquarters. It is asserted that every movement of the Confederate armies was distinctly visible, and instantaneously reported.’38

However, by the end of May 1862, with the Union forces nearing the rebel capital, Richmond, the demand for recreational balloon trips became so great that General McClellan banned all further ascents by newspapermen, and even required Union officers to have his specific written permission to go aloft. Foreign journalists who could boast military backgrounds had better luck, and a notable series of reports were turned in by a British engineering officer, Captain Frederick Beaumont, RE.

Beaumont’s articles appeared in Professional Papers of the Royal Corps of Engineers in 1863, and gave a realistic view of modern warfare. He was also deeply impressed by Lowe, ‘a man celebrated in America as a very daring aeronaut … from the earnest way in which he spoke, I felt convinced that he still intended to carry out his [Atlantic] scheme … but the distracted state of his country obliged him to put it off for a while’.39

Lowe made many attempts to get senior military officers up in his balloons, but most of them declined his offers, especially after Lieutenant-General Fitzjohn Porter’s experience. An exception was a dashing young cavalry lieutenant, a willowy, wild-eyed youth from the plains of Ohio. His long blond hair, silky moustaches and extravagant manner already marked him out. His name was George Armstrong Custer.

This was the man who would become the famous Indian fighter, and would die fourteen years later at the chaotic Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. At the time of his balloon ascent with Lowe in April 1862, Custer was aged twenty-two, and had been temporarily promoted captain by McClellan. He was already wearing his trademark red bandana, and had been noted for his reckless, showy courage in several local engagements on the west bank of the Potomac. But even Custer found the balloon experience oddly disconcerting. He was invited up by one of Lowe’s assistants, James Allen, as he recorded in an unexpectedly witty and self-deprecating memoir.

illustration credit ill.96

My desire, if frankly expressed, would not have been to go up at all. But if I was to go, company was certainly desirable. With an attempt at indifference, I intimated that I might go along … The basket was about two feet high, four feet long … to me it seemed fragile indeed … the gaps in the wicker work in the sides and the bottom seemed immense and the further we receded from the earth, the larger they seemed to become … I was urged to stand up. My confidence in balloons at that time was not sufficient, however, to justify such a course, so I remained sitting in the bottom of the basket…[Mr Allen] began jumping up and down to prove its strength. My fears were redoubled, I expected to see the bottom of the basket giving way, and one or both of us dashed to the earth…

Custer was much struck by the dramatic panorama as he looked west up the entire length of the Virginia Peninsula towards Richmond:

To the right could be seen the York river, following which the eye could rest on Chesapeake Bay. On the left, and at about the same distance, flowed the James river … Between the two extended a most beautiful landscape, and no less interesting than beautiful, for being made the theatre of operations of armies larger and more formidable than had ever confronted each other on this continent before.

But he also noted how difficult it was to make precise observations:

With all the assistance of a good field glass, and when the balloon was not rendered unsteady by the different currents of air, I was enabled to catch glimpses of canvas [tents] through the openings of the forest … the dim outline of an earthwork half concealed by trees which had been purposely left standing on their front. Guns could be seen mounted and peering sullenly through the embrasures … while men [enemy soldiers] in considerable numbers were standing around entrenchments … intently observing [our] balloon, curious, no doubt, to know the character or value of the information its occupants could derive from [our] elevated post of observation.40

The rebel Confederate army was too poor to put any serious balloon opposition into the sky. But it did something almost as effective, by creating one of the most famous romantic legends of the South, the celebrated ‘Silk Dress Balloon’. This remarkable balloon was said to be extraordinarily beautiful, and piloted with fantastic and cavalier daring during the defence of Richmond by the Confederates. It was composed of a shimmering mass of multicoloured silks, supposedly sewn up in homely patchwork fashion from dozens of gorgeous silk ballroom dresses. These dresses, so the story went, had been gallantly donated by the Southern belles of Richmond and the surrounding towns of Virginia, happy to sacrifice the last remnants of their antebellum finery to the cause of Dixie. They included not only the beautiful wives and daughters of the great, porticoed houses of the very wealthy, but also the poor but no less beautiful patriotic ladies of easy virtue. It was, in other words, a balloon made of gleaming Southern dreams.

It has been disputed whether this balloon ever actually existed. Certainly it sounds more like something dreamed up by Margaret Mitchell for Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind. Yet it emerges that just such a small Confederate balloon, romantically named the Gazelle, mysteriously appeared overhead during the desperate battles to defend the rebel capital Richmond between May and July 1862; and its presence became symbolically associated with the final, decisive repulse of McClellan’s Union Army of the Potomac.

illustration credit ill.97

Confederate official records and private correspondence have recently revealed that the Gazelle did in fact exist, and was secretly constructed at top speed in the workshop of a bankrupt armoury in Savannah, Georgia, in May 1862, at the request of General Thomas Drayton. It was built by two Southern patriots: Langdon Cheeves, a merchant from Charleston, Virginia; and Charles Cevor, an itinerant balloonist from Savannah who had once trained under John Wise. A letter from General Drayton, dated 9 May 1862, asks urgently: ‘How soon will the balloon be finished? Put night and day work on it at your discretion.’41

The Gazelle was small and pretty, practically petite, standing about thirty feet high with a 7,500-cubic-foot capacity – roughly half the size of Lowe’s regular balloons. It was composed of long, bright, multicoloured silk strips – yellow, green, white and dark red – some plain, and some carrying decorative patterns. It was sealed with a clear, vulcanised rubber coating removed from old wagon springs, which gave the silk an unusual glisten in full sunlight. It also leaked.

At a time when Union ships were successfully blockading all Southern ports, silk of any kind had been virtually impossible to find. But the merchant Langdon Cheeves had excellent business contacts in Charleston (incidentally, the home of Rhett Butler), and managed to locate a job-lot of twenty mixed bolts of unwrapped dress silk lying in the warehouse of Kerrison & Leiding, wholesale fabric merchants. For these he paid $514. He was still not sure that this would be enough silk for the balloon, and as he left Charleston for the Savannah workshop, he made a gentle, teasing joke to his daughters: ‘I’m buying up all the handsome silk dresses in Savannah, but not for you girls.’42 By the time the Gazelle arrived in Richmond, this wry Southern joke had started the gallant Southern legend.

Robert E. Lee, who would command the defence of Richmond all that summer, placed the Gazelle in the hands of a young Confederate artillery officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Alexander. Alexander knew nothing about balloons, but was a brilliant tactical commander, who would later direct Lee’s artillery at Gettysburg. With him as pilot was Charles Cevor. Alexander decided not only to observe the enemy, but also to raise morale in Richmond.43

The Gazelle was kept inflated, and was run out daily on a railway car along the Richmond and York railroad, right up to the enemy lines beyond Fair Oaks. Everyone in Richmond could see the little balloon going out brazenly to flaunt the rebel flag in the face of the enemy. For once rail and balloon shared a mutual cause. From here Alexander could report on the threatened advances of McClellan’s Union army over the Chickahominy river.44 Tension increased as McClellan’s massive forces manoeuvred into position for the crucial assault. But there was also excitement, as news of rebel reinforcements led by Stonewall Jackson were rumoured to be marching out of the Shenandoah Valley to relieve Richmond.

Just opposite Alexander and the Gazelle, at a distance of less than five miles on the other side of the Chickahominy, was Thaddeus Lowe in his Intrepid balloon. So for the first time, a Union and a rebel balloonist confronted each other, out of rifle shot but well within binocular and telescope range. On 27 June 1862, Lowe telegraphed with astonishment from the Intrepid: ‘About four miles to the west from here the enemy have a balloon about 300 feet in the air.’ An hour later, at eleven o’clock, the rebel balloon had mysteriously disappeared.45

Lowe was stationed at a strategic position known as Gaines Mill.46 The proprietor of Gaines Farm was a medical doctor, and in fact a Confederate supporter, whose cornfields had been forcibly requisitioned by the Union Balloon Corps. It was a sign of the times that Dr Gaines had enough Southern pride to complain about his trampled crop, and that Lowe had enough Yankee style to apologise gracefully for it. He also promised to provide the farm with a protective guard against Union looting. Dr Gaines had a spirited teenage daughter, Fanny, who was fascinated by the enemy balloon camp set up in the middle of her father’s meadow. She showed no nervousness in approaching Lowe, though she took the prudent precaution of addressing him as ‘General’.

Every day the Yankees sent up a balloon in front of our house to see what was going on in Richmond. General Lowe was the man who ascended in the balloon, and he told many wonderful things that he saw going on in Richmond – such as people going to church, the evacuation of Richmond, wagon trains crossing Mayo’s bridge.47

Lowe evidently boasted to Fanny that McClellan and the Army of the Potomac would soon be in Richmond. When Fanny told this to an ancient neighbour, old Mrs Woody, she replied with true Southern scorn, ‘Yes, Moses also viewed the promised land, but he never entered in.’48

Both balloon observers were soon reporting on a bloody series of skirmishes at the river crossing between Gaines Mill and Fair Oaks. The fighting was bitter and confused. It continued through the end of June and the start of July, eventually becoming known as the Seven Days Battle. The rival balloonists were attempting to advise their commanders on the ground about the rapidly developing troop movements and reinforcements, sudden advances and retreats, charges and counter-charges. But it was not easy to understand the action, or even to see it. Alexander believed he was better qualified, as a ‘trained staff officer’, and dismissed his opposite number with Southern scorn as belonging to ‘the ignorant class of ordinary balloonists’.49 But Lowe was experienced, and had the immense advantage of a direct telegraph line from the Intrepid’s basket. ‘Immediately I ascended to a height of a thousand feet,’ he recorded, ‘and there witnessed the Titanic struggle. The whole scene of action was plainly visible and reports of the progress of the battle were constantly sent till darkness fell upon the grand but terrifying spectacle.’50

Inspired by Robert E. Lee, and supported by Stonewall Jackson, the Confederates pushed out from Richmond, crossed the Chickahominy river, and surrounded McClellan’s troops at Gaines Mill. The fighting was unbelievably fierce: on that small wooded hilltop, more than fifteen thousand men were killed or wounded in a matter of hours. Hurrying down the hill from her father’s farm, Fanny Gaines never forgot what she glimpsed: ‘The dead were strewed on every side. I had to keep my eyes shut all the way to keep from seeing the horrible sights.’51

The position was eventually taken by the rebels, in a series of ‘sublime’ uphill charges led first by Jackson, and then consolidated by the flamboyant Texas Brigade from the deep South. The Union troops began to withdraw from Richmond, and Lowe hastily dismantled his balloon equipment. He always believed that his last reports saved hundreds of McClellan’s troops from being cut off and massacred behind the Chickahominy, and that he had prevented retreat from becoming an outright disaster.52

But Lowe’s balloon intelligence had not prevented Robert E. Lee from outmanoeuvring McClellan’s much larger army, nor had it brought about the hoped-for Union victory. Richmond did not fall. The Seven Days Battle was to prove a crucial turning point for Lee. It forced McClellan to abandon his master plan to take the rebel capital, and instead to organise a full-scale Union retreat down the James River. It would also mark the end of McClellan’s own military command, and the eventual disbandment of the Balloon Corps which he had championed.

Lowe was shattered. Exhausted by the strain of what he had witnessed, he succumbed to marsh fever. He did not fully recover his health for many months, and meanwhile his Balloon Corps languished in Washington. By contrast, Alexander and the Gazelle were immediately despatched by Lee on a new adventure. The reputation of the ‘silk dress balloon’ had evidently gained currency among troops on both sides, and the new assignment appears to have had a propaganda as much as a military motive. This time the Gazelle was teamed up with a boat, rather than a train.

On the evening of 3 July 1862 the Gazelle was secretly taken down to a wharf on the James River, and tethered aboard a small rebel tug ship, appropriately named the Teaser, which then steamed all night slowly towards the Union lines, with orders to make ‘stealthy reconnaissance’ of the retreat, and no doubt to add to the Yankees’ shame. The next day, just before dawn, Alexander made a triumphant ascent, rising into the early-morning sunlight until the gleaming multicoloured silks must have been seen for miles. Despite losing gas, he was briefly able to observe the Union retreat, and flaunt his presence. But then things went wrong. On a falling tide, the Teaser ran aground on a mudbank, becoming stuck fast perilously close to the Union lines.

It is possible that Alexander had a chance to fly the Gazelle off from the deck of the trapped Teaser. It would have been a gallant, but probably a doomed attempt. Instead he decided to deflate the balloon completely, and sit tight until the tide turned, hoping to escape detection. It must have been a long wait. After eight hours, in mid-afternoon, just as the tide was flooding back, a Union gunboat, the Maratanza, steamed briskly into view. She immediately loosed off two rounds from her hundred-pound gun, both of which hit home. Having tried to scuttle their ship, the Teaser’s crew, including Alexander, leaped overboard and swam for the shore. There was no hope of saving the Gazelle. Alexander stood watching from the trees, and recalled regretfully: ‘The Maratanza pulled [our ship] out of the mud and carried her off, balloon and all … So I left the sailors, and struck out for the army, which I soon found, and General Lee also; and made my final balloon report.’53

But in a way, this was not the end, but the true beginning of the silk dress balloon. What both Alexander and General Lee soon realised was that the Gazelle, by being physically destroyed, had become mythically indestructible. As such, it was infinitely more valuable to the South, safely afloat as a provoking and permanent piece of rebel propaganda among the enemy. Indeed, it was the Union commander of the Maratanza who made the first known reference to a ‘silk dress balloon’ in print, thus unwittingly making its existence official. He reported to his superior officers on 16 July 1862: ‘The Confederate officers and crew … left everything behind. We got the officers’ uniforms, swords, belts, pistols, muskets, silver chains, bedding, clothes, letters…We also found a balloon made of silk dresses.’54

Lowe was clearly impressed by the truth of the story as well. He added a circumstantial, and curiously wistful, note to his memoirs, My Balloons in Peace and War: ‘The fashions in silks at that period were ornate, large flowery patterns, squares and plaids in blues, greens, crimsons etc, and rich heavy watered silks; and the silk dress balloon was a very brilliant and handsome object – a veritable Joseph’s coat of many colours. It was taken to Washington and cut up, many pieces being given to Congressmen and others as souvenirs.’55 Thus the myth was soon dispersed and spread, a sacred relic of the Old South: beautiful, gallant, self-sacrificing, doomed.*

illustration credit ill.98

Thirty years after the war, the Confederate General James Longstreet, who had fought alongside Jackson and Lee in the defence of Richmond, delightfully retold and embroidered the now well-established silk dress story, in cadences that catch the authentic voice of the Old South:

The Federals had been using balloons in examining our positions, and we watched with envious eyes their beautiful observations as they floated high up in the air, and well out of the range of our guns. We longed for the balloons that poverty denied us. A genius arose for the occasion and suggested that we send out and gather together all the silk dresses in the Confederacy and make a balloon … Soon we had a great patchwork ship of many and varied hues … The balloon was ready for the Seven Days Campaign. We had no gas save in Richmond, and the custom was to inflate it there, tie it securely to an engine, and run it down the York River railroad to any point at which we desired to send it up. One day it was on a steamer down the James when the tide went out and left the vessel and the balloon high and dry on a bar. The Federals gathered it in, and with it the last silk dress in the Confederacy. This capture was the meanest trick of the War, and one I have never yet forgiven.57

For Longstreet, the capture of the Gazelle by the Union gunship on the James River was not an act of war, but an act of ungallantry, amounting almost to an insult, as if a fine Southern lady had been betrayed and abused by a Yankee carpetbagger.

The poetic possibilities of balloons also occurred to Walt Whitman, who was working during these months as a hospital orderly in Washington. Though he often saw Lowe’s balloons on the horizon, he never had the chance to go up himself. But he imagined being in a balloon basket, calmly surveying the land and the rivers of the peninsula beneath. He sees no battlefields, but instead is given moments of detached, surreal vision, as described in A Song of Myself:

Where the pear-shaped balloon is floating aloft,

(Floating in it myself and looking composedly down,)…

Where the steam-ship trails hind-ways its long pennant of smoke,

Where the fin of the shark cuts like a black chip out of the water.58

By contrast, Stephen Crane, who wrote extensively about the Civil War, presents a balloon as viewed from below. It is seen by the ranks of an advancing infantry brigade, just about to go into battle. Though it is one of their own balloons, its appearance is unnerving, and almost repulsive. It seems an alien presence, presiding over a human sacrifice. It is the signal for the ritual of killing to begin.

The military balloon, a fat, wavering yellow thing, was leading the advance like some new conception of a war-god. Its bloated mass shone above the trees, and served incidentally to indicate to the men at the rear that comrades were in advance … The first ominous order of battle came down the line. ‘Use the cut-off. Don’t use the magazine until you’re ordered …’ A sound of clicking locks rattled along the column. All men knew that the time had come.59

This story in fact draws on Crane’s experience with troops in Cuba during the 1890s. No balloon appears in The Red Badge of Courage, which is a historical fiction, as Crane was born well after the end of the Civil War, in 1871. Nevertheless, the superb opening paragraph of the novel, a brooding panorama of an army encamped by a river like the Potomac, seems to draw on a balloonist’s aerial view. The whole army is seen awakening from winter slumber (with a repeated imagery of opening ‘eyes’); yet no individual soldier, horse or wagon appears. As from a balloon, what is seen is the pattern of mobilising forces. Both man and nature appear as anonymous combatants. It is just as Lowe might have seen the Union army in the spring of 1862.

The cold passed reluctantly from the earth, and the retiring fogs revealed an army stretched out on the hills, resting. As the landscape changed from brown to green, the army awakened, and began to tremble with eagerness at the noise of rumors. It cast its eyes upon the roads, which were growing from long troughs of liquid mud to proper thoroughfares. A river, amber-tinted in the shadow of its banks, purled at the army’s feet; and at night, when the stream had become of a sorrowful blackness, one could see across it the red, eyelike gleam of hostile camp-fires set in the low brows of distant hills.60

The Union Balloon Corps did have one significant effect on the future of warfare. Among the military observers sent to the Union army was a young Prussian officer, who took some part in the fighting around Fredericksburg in 1863, and saw the last of Lowe’s balloons in action. Later he ascended in one of John Steiner’s civilian balloons at St Paul, Minnesota, above the Mississippi. The experience was a great success. He admired the picturesque effect of the great river, but was even more impressed by the opportunities for ‘military reconnaissance’. He noted: ‘From the high position of the balloon the distribution [of the defenders’ troops] could be completely surveyed … No method is better suited to viewing quickly the terrain of an unknown enemy in occupied territory.’ The only problem was the inability to navigate a spy balloon. This started a chain of ideas that would have a considerable effect on the use of balloons in the First World War. The young Prussian’s name was Captain Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

* Lowe added a further note towards the end of his life, while completing his memoirs as an old man in California: ‘As I write, a good piece of it lies before me on the table, now frail and discoloured with age.’ It is easy to imagine him turning this last fragment of the silk dress balloon carefully with his fingertips. I found it strangely moving to discover that very piece, a stiff section of dark-red material about the size of a playing card, folded into one of his letters, and still stored in the Library of Congress Archive, Washington, in 2010. It is not surprising that the story has inspired at least one modern romance, The Last Silk Dress (1988), by Ann Rinaldi, later retitled as Girl in Blue. Here the coloured silk dresses are even identified with their individual owners, as the balloon comes to life: ‘The men on the dock were spreading the silk out, making it smooth. You could see the bright coloured patches, jumping and bubbling … Lying there on the dock, the crazy patchwork mass of material was like something alive. The men had all they could do to hold it down as the gas hissed in … We stood and watched as fold by fold of the balloon took life and it rippled into a mass of shimmering, bouncing silk … Connie screamed in delight and pointed out Francine’s green, Lulie’s striped pink, and all the other colours we recognized from the girls at Miss Ballard’s … The balloon was taking on a life of its own.’56

Almost unnoticed, the Civil War brought to an end a golden era in American ballooning. For a brief period in the 1840s and 1850s, the balloon seemed to hold the magic key to the unlocking of the whole vast American continent, ‘from sea to shining sea’. But the logistical demands of warfare had revealed the imperative necessity of modern communication networks: the telegraph, the railroad, the steamship. The business potential, as well as the visionary moment, of the balloon was gone.

The aeronauts responded to this each in their own way. John LaMountain, brave but cantankerous, struggled on briefly as a balloon showman, increasingly underequipped and underfinanced. After one of his worn-out balloons burst above Bay City, Michigan, in 1869, nearly killing him, he returned to New York State, and after various minor commercial ventures died, a forgotten figure, aged only forty-eight, in 1878.61

John Wise, nearly sixty by the end of the war, largely confined himself to giving lectures on the history of ballooning. In 1873 he published his admirable book, part history and part autobiography, Through the Air: A Narrative of Forty Years’ Experience as an Aeronaut. His actual attempts to return to the air were less happy. In September 1879, aged seventy-one, he took off in another balloon from St Louis, in an attempt to commemorate the famous flight of the original Atlantic twenty years before. No doubt he hoped to make the full thousand miles to New York or Boston, but this time he strayed even further from his projected easterly course. Once again he headed northwards towards the Great Lakes, and once again he was caught in a gale. He was last observed near Chicago, sailing in high winds out across the enormous stormy expanse of Lake Michigan, and trusting in the Lord. Neither he, nor his balloon Pathfinder, was ever seen again. Perhaps it was the heroic conclusion that he desired. ‘Astra Castra, Numen lumen’, as he had written.

Despite the long after-effects of his fever, Thaddeus Lowe made the most successful career adjustment. Part scientist, part entrepreneur, part adventurer, his navigation skills stood him in good stead. First, he shrewdly turned down a tempting, but surely doomed, Brazilian government invitation to start a military balloon corps in São Paulo. Though personally invited by Don Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil, with many blandishments, he passed the invitation on to his fellow balloonists the Allen brothers, remarking with a wry smile, ‘I think I am rather beyond the age of adventure.’62

Next, he briefly promoted a spectacular ‘Aeronautic Amphitheatre’ in New York City. Here his last ever balloon flight was made in 1866 for a wealthy honeymoon couple, to take them, as he put it, ‘nearer to heaven than most clergymen ever get’. The flight lasted most of a summer’s day, and finished on a perfect idyllic note: ‘We sailed high over cities, hills, valleys and rivers, and came to earth with the sunset.’63

But Lowe the entrepreneur was far from finished. Still determined to explore the vastness of America, he went west to Los Angeles, seeking business opportunities. Here he used his knowledge of the chemistry of hydrogen to invent a brilliantly successful ice-making machine. An early version was used to refrigerate cargo ships steaming from San Francisco around Cape Horn to New York. In its own way this fulfilled his original transcontinental dream. Instead of mail, he was transporting food across the whole continent. His perfected ‘Lowe’s Compressed Ice Machine’ was sold to all the newly opening stores and hotels of California, and made him a dollar millionaire. It also won him the Franklin Institute’s Grand Medal of Honour in 1887.64

illustration credit ill.99

The same year, at the age of fifty-five, a successful businessman, he settled with his faithful wife Léontine and their extensive family in Pasadena, at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains. Here he built a luxury estancia, and subsequently invested his fortune in a different form of elevation – a funicular, or scenic mountain railway, climbing into the hills above Altadena. It was to service an ‘Alpine Tavern’ and a forty-room luxury hotel, with panoramic terraces. This mountaintop complex, with its dazzling aerial views, was opened in July 1893 and publicised as ‘The White City in the Clouds’. Perhaps, in a way, Thaddeus Lowe considered it his final version of an enormous tethered balloon.65

Lowe kept up his scientific contacts with the Smithsonian, continuing to correspond with Professor Joseph Henry, and wrote a long, racy aeronautical memoir entitled My Balloons in Peace and War. Typically, he never bothered to publish it. But the manuscript, treasured by his family and transcribed by one of his granddaughters, Augustine Lowe Brownbeck, eventually reached the Library of Congress in 1931.

Lowe lived on comfortably in Pasadena, saw the coming of the Zeppelin and the aeroplane, and died peacefully in 1913, at the age of eighty. But he never quite stopped dreaming. Almost his last act was to form a new business company: the ‘Lowe Airship Construction Corporation’.66

The crossing of the American continent, so long dreamed of by Lowe, Wise and LaMountain, was never actually accomplished in the nineteenth century.* It was, however, achieved in fiction, as so often in ballooning. A novel by Jules Verne, The Mysterious Island (1875), opens with five men (and a dog) escaping by balloon from the besieged Confederate city of Richmond in the spring of 1865. The balloon, at fifty thousand cubic feet, is considerably bigger than the Gazelle, and the men are escaping Union prisoners. To lend verisimilitude, one of them is a war reporter for the New York Herald.

Stealing a rebel balloon at night, they launch in a terrible storm, which is described by Verne with vivid details drawn from the apocalyptic journey of Wise and LaMountain across the Great Lakes. But this storm is blowing from east to west, and it sends the balloon at ninety miles per hour right across America the other way: the Great Plains, the deserts, the Rocky Mountains, and out over the Pacific Ocean, where eventually it touches down on an unknown island. But ironically, because of the stormclouds, its passengers spy absolutely nothing of that entire great American land passing beneath them.

* For the record, the nearest thing to an actual non-stop trans-American balloon flight did not take place until May 1980. The helium-filled balloon travelled west to east, just as Professor Henry and John Wise had always prophesied. The Kitty Hawk was flown by Maxie Anderson and his son Kristian, for four days and nights, from Fort Baker in California to Sainte-Félicité in Quebec, a distance of 3,313 miles. Anderson had also been the first to fulfil the transatlantic dream. In 1978 he flew with Ben Abruzzo and Larry Newman in Double Eagle II, from Maine to Picardy in northern France, a distance of 3,107 miles. Their insulated gondola is displayed in the Udvar-Hazy Center, Dulles International Airport, Washington, DC. His and Ben Abruzzo’s names live on in the new Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque International Balloon Museum in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where the greatest of all American balloon fiestas is based. Anderson also founded the Anderson Valley Vineyards, which marketed a famous aeronautical rosé wine, christened ‘Balloon Blush’. It is surprisingly dry.