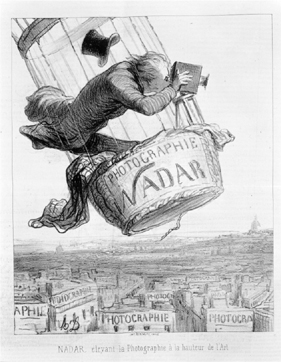

The lack of any aerial photographs from the American Civil War is a curious anomaly. For as early as 1858 the first aerial photograph of Paris had been taken from a balloon by a strange, daredevil figure who called himself Félix Nadar. Nadar (the name was one of his many inventions) eventually persuaded his friend, the distinguished artist Honoré Daumier, to draw a cartoon in celebration of this achievement. It appeared as a lithograph in the popular magazine Le Boulevard in 1862, and became one of Nadar’s most treasured mementoes.

illustration credit ill.100

In it, Nadar’s unmistakable gawky figure is shown perched in a tiny balloon basket above the rooftops of Paris. Top hat flying, he is clinging onto a spindly photographic apparatus mounted on a tripod. The balloon basket – emblazoned with his name – swings perilously above an imagined Parisian cityscape, which seems largely composed of photographic studios. The caption reads wittily: ‘Nadar elevating Photography to the height of Art.’

Nadar had a genius for elevating things. He was one of the earliest masters of the new nineteenth-century art of visual publicity. He turned unknown people into celebrities, and gave new ideas public prominence, largely by fixing them with memorable imagery. Even his own name was created as a visual logo to publicise his work. The one-word signature ‘Nadar’ was carefully designed with a long, forward-racing letter ‘N’, to express his particular energy and enthusiasm. He actually copyrighted this logo signature, once fought a court case to retain control of it, used it on the covers of his books, and had it incorporated into an early form of red neon sign above his Parisian studio by Antoine Lumière.1

Born in April 1820 into a prosperous family of Parisian printers, recently established in the fashionable rue Saint-Honoré, Nadar was christened Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, and schooled in the latest techniques of printmaking and print advertising. Self-confident, sociable and highly original from the start, he broke away into the world of literary bohemia, and soon became known for his wild ideas, his immense height and his memorable shock of carrot-coloured hair. He was already a kind of walking logo. He plunged into radical politics and satirical journalism, and took part in the revolutionary street disturbances of 1848 in Paris, always remaining a republican. But his visual and business talents soon emerged, and by his mid-thirties he had established himself as a brilliantly inventive cartoonist, caricaturist and commercial artist.

From 1851 the Paris of the Second Empire saw an explosion of newspapers, illustrated journals and satirical magazines, such as La Silhouette, Le Charivari, La Revue comique and Le Journal pour rire (the equivalent of the modern Le Canard enchainé and Charlie hebdo). Nadar exploited these with astonishing energy and flair. Commissioned by leading Parisian editors such as Charles Philipon, he drew cartoons of all the leading celebrities of the day. Already thinking in ‘panoptic’ terms, he chose figures from every artistic field of endeavour for which Paris was famous: painting, music, theatre, opera and literature. These early portraits-chargés were signed by an early version of his logo, with his name altered from Tournachon to ‘Tournadard’. This might be translated as ‘Jab-the-barb’, although his caricatures were for the most part gentle and humorous, even flattering. His subjects faithfully collected the originals.

Nadar then had the genius to combine them all into a single, enormous cortège: Le Panthéon Nadar, a true panoptic vision. He published this independently, as an expensive and hugely popular poster, in 1854. It made his name, and established his logo. He was now almost universally known, especially among the writers of the day. Baudelaire, Hugo, Gautier, Nerval, Dumas, the Goncourts, George Sand and – notably – Jules Verne, were all to become personal friends. And they were all also to be photographed.

Alive to all new technical developments, Nadar saw the possibilities of photography – ‘writing with light’ – as a novel means of portraiture, and also of publicity. With the arrival of the wet-plate collodion method in the early 1850s, it was possible to take a photograph in less than thirty seconds, rather than the several minutes that daguerreotypes had previously required. Individual photographic portraiture – not merely a superficial ‘likeness’, but a study of personality in depth – became practicable. Nadar saw both the immense artistic and commercial potential of this. He swiftly mastered the techniques, and ‘exchanged the pencil for the camera’. In January 1855 he opened a fashionable photographic studio at 35, boulevard des Capucines. At the same time, he also fought a successful legal battle against his younger brother Adrien to retain exclusive rights to his logo ‘Nadar’, and installed his first illuminated ‘Nadar’ sign above his premises.2

It was a shrewd move. Nadar quickly became the most famous portrait photographer in France. Between 1854 and 1860 he photographed nearly all his celebrated friends, compiling a matchless Album Nadar. It was said that while André Disderi was the official ‘establishment’ photographer (politicians, generals, aristocrats, wives), Nadar was the official ‘opposition’ photographer (writers, actors, painters, mistresses). Victor Hugo – himself always a republican – sent letters to him from Belgium or the Channel Islands addressed simply to ‘Nadar, Paris’.3

Determined to master the whole photographic field, Nadar had been secretly struggling with aerial photography, on and off, since 1855. He worked from a small hydrogen balloon, provided by Louis Godard, tethered above an apple orchard in the village of Petit-Bicêtre, outside Paris.4 Since the clichés, or glass photographic plates, had to be prepared and painted with the wet collodion gum on the spot, that is to say while actually in the air, Nadar had immense difficulties. It was not a question of breakages, but of contamination. For a long time the escaping gas from the balloon contaminated his developing chemicals, and rendered all his plates black after exposure. After endless experiments, he hit upon the solution of closing the balloon’s escape valve and fitting a special kind of thick cotton insulating tent to the basket.5 He described the intense excitement of his first success in a memoir, When I Was a Photographer:

It’s just a simple positive on a glass plate, very feeble in this misty atmosphere, all blotchy after so many false starts. But what does that matter? The evidence cannot be dismissed. There beneath me, the only three houses in the little hamlet: the farm, the inn and the police station. It’s the unmistakable image of Petit-Bicêtre. You can clearly make out on the road a furniture cart whose driver has come to a halt directly below the balloon, and on the tiles of the rooftops two white pigeons which have just alighted there. Yes, I was right!6

Nadar was much concerned to establish commercial priority for his invention, and made wildly extravagant claims about the exact date on which he achieved this technical breakthrough, for example as early as autumn 1855. But the only reliable documentary proof is his French patent, which was first registered on 23 October 1858. The patent referred to a ‘special combination of equipment’ taken up in a balloon, which would allow him ‘to employ photography for the production of topographical plans and cadastral surveys, and also for the direction of strategic military operations, for the erection of fortifications, and the disposition of armies on the march etc.’ The camera would be mounted ‘perpendicularly in the balloon car’, either fixed ‘laterally on the outside’, or else positioned ‘at the bottom of the car using a perforated section’.

Nadar also patented a ‘sliding lens shutter’ to allow the camera to be operated automatically; a black cotton tent for preparing the plate, and also a yellow one for developing it afterwards. The whole operation could thus be performed within the balloon basket, and the aeronaut could descend to earth with the finished glass negative. The design was of course very far from the flapping, comic tripod wittily imagined by Daumier.7

The following spring, 1859, Nadar claimed he was able to take a further historic series of Paris photographs from several hundred feet above the Right Bank. He recorded these simply as ‘several views of the Bois de Boulogne, Arc de Triomphe, and perspectives on the place des Ternes’. They are not of fine quality, but have a surprisingly long perspective to the north of the city, and have been proudly annotated to show the place des Ternes, the Parc Monceau and the heights of Montmartre in the far distance.8

But again, the date Nadar gave is not certain. If he really did take his first aerial photographs in 1858, it is curious that the Daumier cartoon is dated 1862. Nadar did not return to aerial photography until 1868, when a second, much-better-quality set, clearly showing the Arc de Triomphe, is well documented. So there remains some dispute over who actually took the first successful aerial photograph from a balloon. On 13 October 1860 James Black and Samuel King flew in their balloon Queen of the Air over Boston harbour, and took a series of high-quality photographs of the roofscapes and ships immediately beneath. The best of these was subsequently widely distributed in an oval frame as ‘Boston, As the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It’, and soon gained the reputation of being ‘the first ever aerial photograph, 1860’. Yet no balloon photographs of Civil War battlefields, over the next five years, are known.

illustration credit ill.101

As for Nadar, in a typical volte-face, he left the air and went underground to photograph the Paris sewers and catacombs, taking out a first patent on ‘photography by artificial lights’ on 4 February 1861. He sold a set of eight photographs entitled ‘Paris Overhead and Underground’ to a minor Brussels publisher on 25 October 1866, which suggests his aerial photos were well known by that date. A cartoon by Cham shows two Parisians on a boulevard, one peering down into a manhole, the other gaping upwards into the sky. The first turns to the second: ‘Are you looking for Monsieur Nadar? He ain’t up there! He’s down here!’9

Nadar was rarely content to pursue one scheme at a time. His quick mind had already moved on to a new publicity challenge. He began to think about ballooning itself, and by extension the whole question of sustained and navigable flight. Was it possible? He had always been fascinated by balloons, having first seen one in Paris at the age of eight or nine during the Fête du Roi of 1829. It flew very low down the Champs-Elysées, grazing the treetops and followed by a shouting, ecstatic crowd. He was much struck by the people’s reaction, and thought afterwards that the publicity possibilities of such an event were huge.10

illustration credit ill.102

With undimmed boyish enthusiasm, Nadar threw himself at this age-old question in aeronautics. Could a balloon, a ‘lighter than air’ machine, ever truly be navigated? And if not, what kind of ‘heavier than air’ machine must be invented to replace it? To address this debate in his own unique way, Nadar undertook three quite different forms of publicity campaign. The first was fairly modest: he set up a discussion group, founding the Society for the Promotion of Heavier than Air Locomotion, which began meeting at his studio in July 1863; Jules Verne was a member of the steering committee. Then, the following month, Nadar launched a beautifully illustrated review, L’Aéronaute, dedicated to the challenge of flight in all its aspects. Its first issue had a cover designed by Gustave Doré. Finally he began construction of a truly enormous gas balloon, Le Géant (‘The Giant’), to demonstrate both the capabilities and the limitations of aerostation.11

As part of his campaign, Nadar circulated photo-portraits of himself as a gentleman balloonist. These were not shot perilously en plein air, but safely in his studio at the boulevard des Capucines. He appears incongruously in top hat and evening dress, with a warm tartan plaid casually over one shoulder, and an expensive pair of opera glasses to hand. His large frame is elegantly posed in a wicker observation basket against a background of delicately painted clouds. The effect is unexpectedly comic, but this may have been exactly Nadar’s intention. It is in its own way a photographic caricature: the balloonist as aerial flâneur, a gentleman of the upper air, a voyageur extraordinaire.

illustration credit ill.103

In the same mode, Nadar published a spectacular ‘Manifesto of Aerial Autolocomotion’ in a winter 1862 edition of La Presse, announcing his Géant scheme. It is presented as a disinterested scientific project, undertaken purely at his own expense, but with obvious commercial potential internationally (for anyone who might care to invest). At the same time Nadar makes witty use of hyperbole, so it can also be read as a brilliant and playful piece of advertising copy:

I shall construct a balloon – the last word in balloons – in proportions extraordinarily gigantic, twenty times larger than the largest hitherto known. It will realise what has only been a dream in the American journals; and it will attract, in France, England, and America, those vast crowds that are always ready to run to witness even the most insignificant balloon ascents.

In order to add further to the interest of the spectacle – which, I declare beforehand, without fear of contradiction, shall be the most beautiful spectacle which it has ever been given to mankind to contemplate! – I shall dispose under this monster balloon a small balloon (or balloonette) designed to receive and preserve the excess of gas produced by dilation. Instead of losing this excess, as has hitherto been the case, this will permit my balloon to undertake genuinely extensive voyages, instead of remaining in the air two or three hours only, like our predecessors.

I do not wish to ask anything of any private investor, nor of the State, to aid me in this proposal of such general, and also of such immense scientific interest. I shall endeavour to furnish entirely by myself the enormous sum of two hundred thousand francs necessary for the construction of my balloon. Once my balloon is completed, I am confident that a series of well-publicised ascents and successive exhibitions at Paris, London, Brussels, Vienna, Baden, Berlin, New York (and anywhere else I can think of) will generate ten times the funds necessary for the construction of my next scheme: our first true [heavier-than-air] aerolocomotive.12

Le Géant was designed and piloted by the leading French aeronauts Louis and Jules Godard.13 Nadar was careful to publicise the precise financial and technical details of its gigantesque construction, knowing that such lavish extravagance had a particular appeal in the Second Empire. The balloon was made of twenty-two thousand yards of silk, costing the equivalent of five shillings and fourpence a yard, making its price alone almost £6,000. This was cut into 118 gores, which were entirely hand-sewn with a double seam. Two hundred women were employed for a month in the sewing of the gores. For the sake of greater strength, the silk was doubled. In other words, there were two balloons of the same size, one within the other. The vast envelope contained 212,000 cubic feet of gas and stood approximately 196 feet in height when fully inflated. This was well over twelve storeys high (nearly the height of the first platform of the Eiffel Tower when it was built in 1887). It was a truly fantastic sight, visible for miles above most of the surrounding buildings of Paris. It was the biggest logo that Nadar had ever imagined.14

Nadar’s deployment of all these hard facts and figures was carefully set against a personal narrative which appealed directly to the sympathies of his readers. He turned the whole construction process into a gripping drama.

I have set myself to work immediately, constantly and with great difficulties, suffering sleepless nights and daily vexations. These I have kept to myself up till now, but one day this winter when the most urgent part of my task is completed, I shall reveal all to my readers. I have succeeded in establishing my balloon, and in simultaneously founding this journal – L’Aéronaute. It will become the indispensable guide to aerial autolocomotion. And I shall have laid the basis of that which shall be, perhaps, the greatest financial operation of the age. Those who see and appreciate these labours, will I hope pardon their Nadar, for wiping the sweat from his brow with a little gesture of pride! In one month’s time, a mere one month! – I shall announce: ‘C’est fait! It is accomplished!’15

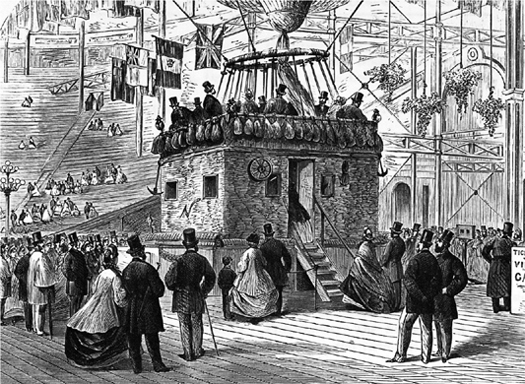

Nadar commissioned a spectacular wickerwork gondola to house paying passengers in the greatest possible comfort. The gondola expressed something of Nadar’s childlike enthusiasm and fantasy. It looked less like a conventional balloon basket than a fairy-tale cottage out of a children’s illustrated book. (Admittedly, some critics said it looked like a small garden shed.) It was thirteen feet long, eight feet wide, and ten feet tall – but somehow looked bigger and more mysterious than these prosaic dimensions. It was constructed on two levels, with an open-top sundeck like a kind of aerial balcony, and an enclosed lower deck like a ship’s cabin.

The cabin had a central entrance door, and several little windows or portholes. It could be divided by partitions into a maximum of six separate compartments, and the extensive fixtures were altered according to the requirements of different voyages. Besides the captain’s compartment with a navigation desk, it contained at various times a set of guest bunk beds, a small printing press, a photographic studio, a galley kitchen and wine store, and – most important last touch of luxury – a portable lavatory. The upper deck was reached by an internal ladder. Nadar claimed that Le Géant could carry up to twenty people, and had a lifting capacity of four and a half tons. The original is still proudly kept on display at the Musée de l’Air at Le Bourget, Paris.16

The maiden voyage of Le Géant started from the Champ de Mars at 5 p.m. on 4 October 1863, with fifteen passengers and many crates of champagne aboard. The flight lasted five hours, and came down near Meaux (the mustard capital) before midnight, instead of flying on till dawn as planned. But the occasion was a masterpiece of Nadar’s commercial and publicity skills. Each passenger agreed to pay a thousand francs. Despite a ‘no women or children’ rule, Nadar shrewdly accepted at the last moment a fashionable and glamorous young aristocrat, la Princesse de la Tour d’Auvergne. He also distributed ‘a hundred thousand’ copies of a special number of his review L’Aéronaute to a huge crowd of paying spectators. His receipts amounted to thirty-seven thousand francs, although, as expected, these did not cover half his costs. But the press coverage was global, reaching even the Scientific American.17

illustration credit ill.104

Taking advantage of the immediate publicity, Nadar launched the second flight of Le Géant a fortnight later, on 18 October. This time he announced a sustained long-distance voyage eastwards: Germany, Austria, Poland, even Russia were all possible destinations. The balloon supplies were fully restocked, but this time there were only six people on board. It was something like a professional crew: the balloon’s two designers, the brothers Louis and Jules Godard, a member of the Montgolfier family, a reporter, Théobald Saint-Félix, Nadar himself and – rather surprisingly – Nadar’s young wife. Nadar’s public relations had been masterly: the spectacular sunset lift-off was witnessed by no less than the Emperor Napoleon III himself, and the King of Greece, both VIP guests in a special enclosure.18

Le Géant sailed rapidly north-eastwards across Paris and towards the Belgian border. Nadar records that they took supper on the sundeck and opened no fewer than six different cases of vintage wine supplied gratis by the Paris wine merchant Courmeaux (just one of many examples of his skilful marketing). After nightfall, like Green in the Nassau, they watched with fascination as they passed over the fiery Belgian ironworks.19

Just before dawn they were over Holland, and mildly worried about floating out over the North Sea. But the wind veered to a more south-easterly direction, carrying them inland into Germany in the direction of Hanover. It also stiffened considerably, though this was not evident at four thousand feet, and when the sun came up the passengers took a tranquil breakfast of coffee and croissants on the sundeck. After some discussion, the Godards decided to attempt a landing in the open countryside before they reached Hanover. Nadar later claimed that he had serious reservations about this, and wanted to continue much further east, according to the original plan; waiting till the wind dropped, and at least crossing the Rhine.

As they valved gas and descended, it became clear how alarmingly fast Le Géant was travelling over the ground. It was a situation very similar to that experienced by Wise on the foreshore of Lake Ontario, though with a quite different outcome. Unused to the aerodynamic properties of the enormous balloon, the Godards had released too much gas, and left themselves too little ballast to recover height. They found themselves committed to a very rough landing near the village of Nimbourg. The passengers were instructed to come up from the cabin, and brace themselves around the sides of the sundeck, holding on tightly to the special leather hand-grips. They let down both the enormous grapnel irons, and hoped for the best.

The huge balloon brushed the ground and rebounded. It instantly ripped off both its grapnel anchors, and began careering over the open farmland at an estimated speed of thirty miles an hour. This might not sound very fast, but for Nadar and his passengers it was like being attached to a wild animal that had gone completely berserk.

It is worth remembering at this point that the balloon was nearly two hundred feet tall. As it was still partially inflated – the Godards had not supplied a rip-panel – it continually bounced fifty feet into the air and came crashing back down in a series of giant leapfrogs. When trees got in its path it simply tore off huge branches and lunged on. Everyone on board was paralysed with shock. From below them in the cabin came the sound of smashing crockery, furniture and equipment. One side of the sundeck was ripped off, so the passengers tried clinging to the balloon rigging above their heads. In the confusion, Nadar lost hold of the valving line. Jules Godard made three attempts to climb into the hoop to retrieve it. Meanwhile the nightmare journey continued.

In a narrative development that Verne would have appreciated, the balloon was now blown into the path of an approaching express train. They were travelling at right angles to the track; the alert train driver spotted the monster bounding towards him across the fields from the west, and correctly calculated that to avoid a fatal collision, he must slow down rather than accelerate. He applied the emergency brakes, and halted the train in time for the balloon to bounce across the tracks directly in front of the engine. They were so close to the driver’s cab that through the cloud of steam they could hear him yell a warning in German. Nadar worked out that he was shouting ‘Mind the wires! Mind the wires!’20

Indeed, the balloon basket was now hurtling towards a line of telegraph wires running parallel to the railway track. Nadar glimpsed them approaching at head height, and a single grotesque thought flashed through his mind: ‘Four electric wires – four guillotines!’ He grabbed Madame Nadar.

We lower our heads, crouching down … By fantastic good luck at that precise moment we skim back towards the ground. The wires strike just above us, at the level of the balloon hoop and the small gabion fastenings. Only one or two of the leading balloon cables are cut by these slashing razors, which are immediately torn up and dragged along behind us – like the flying tail of a crazed comet…21

To Nadar’s amazement, the force of the balloon uprooted the two telegraph poles on either side of them, and the whole hissing tangle of wires and poles was dragged along for several seconds. Having shed them, Le Géant continued its terrible, headlong course for a further ten miles, continually leaping into the air and then smashing the gondola onto the ground. One by one the passengers jumped or were thrown out, until only Nadar and his wife remained, clinging to each other and curled up in a foetal position in a corner of the sundeck, their hands locked onto the remaining pieces of wickerwork.

Le Géant, now reduced to a long flailing tangle of ropes and silken canopy, finally tore into a dense thicket of woodland, and was shredded between its branches. The wreckage came to rest in a clump of trees, the battered gondola lying on its side, bodies and pieces of wickerwork strewn in a long trail behind it. It had travelled four hundred miles in fourteen hours, at speeds ranging between twenty and sixty miles per hour. Every one of its passengers was injured, although inexplicably none was dead.

News reports were telegraphed to journals all over the world, including La Vie Parisienne, the Illustrated London News and the newly founded New York Times. The Scientific American carried a gripping (but slightly inaccurate) stop-press item: ‘Second voyage of the Géant. Seventeen hours and two hundred and fifty leagues. Landing near Nieubourg in Hanover. Balloon dragged for several hours. Nadar suffered fractures to both legs, his wife a deep wound to the thorax.’22

illustration credit ill.105

Paradoxically, this was just the kind of story that Nadar could turn into brilliant publicity. The moment he and his wife got back to Paris (by train) he began working on his Mémoires du Géant (1864). His detailed description of the crash-landing occupied no less than thirty-two pages, and ends with the dramatic admission that at first he thought he had been responsible for his wife’s death. In fact she was slightly concussed, and cut under the chin, but not otherwise hurt.23 He wrote the book while recovering from his own leg injuries, which were more severe, and took several months to heal. For good measure, he also brought a lawsuit against the pilot, Jules Godard, for incompetent balloon management. Surprisingly, none of the other passengers brought a lawsuit against Nadar.

Nadar saw that in narrative terms, the climactic moment was the encounter with the express train. Accordingly, he commissioned his brother Adrien to compose a semi-documentary drawing of this, carefully assembling all the elements into a single image of imminent peril. The viewpoint is dramatically from above, as if from another balloon. The dark shape of the Géant, bent over sideways and grotesquely distorted by the howling wind, almost fills the picture. It looks like some blind, maddened creature rushing across the fields, casting a huge shadow, and terrifying a flock of sheep and a pair of horses. The gondola drags along helplessly in its wake, leaving behind a trail of shattered trees. In front of it the steam engine, tiny by comparison with the huge balloon, thunders down the track under a flattened plume of steam. The near-fatal telegraph wires are just visible in the balloon’s path.

illustration credit ill.106

Nadar carefully copyrighted this image, which appeared in journals all over Europe during the winter of 1863. He also used it as the frontispiece to his book when it was published eight months later, in the spring of 1864. It had become the symbol – the logo – of the flight. He had the balloon and basket repaired and refitted, and over the next four years Le Géant made further demonstration ascents from Brussels, The Hague, Hanover, Meaux and Lyons. When it flew from Amsterdam, the publicity posters were distributed as far afield as Geneva and Marseille.24 Nadar had broken with the Godard brothers, and instead employed Camille d’Artois as his pilot. There were no further aerial dramas. Despite the understandable objections of Madame Nadar, he went up again himself from the Hippodrome at Lyons on 2 July 1865.

What Nadar now decided to do was ingenious. He would use the story of the Géant to demonstrate that ballooning was superannuated as a concept. A lighter-than-air machine would publicise the heavier-than-air cause. Indefatigable, Nadar set out to write a different kind of campaigning tract, Le Droit au vol, ‘The Right to Flight’. This made the case for the ‘aero-locomotive’ as against the balloon. The title also neatly implied that flight had somehow become one of the Rights of Man. He coopted George Sand to write the Preface. She did so with a flourish, but later wrote to him privately, on 28 September 1865: ‘Dear Nadar, I must beg you to renounce these terrible balloon-antics that worry your friends far more than you realise. I beg you to go back to photographic portraiture! Mine for example …’

Le Droit au vol promoted Nadar’s new conviction that flight would only reach its full potential when a true ‘aircraft’, powered by an engine, was invented. Such an aircraft or airship, powered by a steam, electric or even gas engine, would necessarily be heavier than air, and would at long last provide the fully navigable vehicle that balloonists had been seeking for over a hundred years. Just like an ocean-going ship, an airborne ship could be steered by rudders working against the airflow. Thus it would become a ‘dirigible’ – a new word that conveniently worked in both French and English. In fact, with rudders and elevators, it could be steered in three dimensions. Exactly what this machine would look like, no one yet knew. But it would not look like Le Géant.

illustration credit ill.107

Nadar turned to the most controversial and celebrated writer in France to back his cause. Victor Hugo was a loyal friend from the days of the Panthéon Nadar, and Nadar wrote to him requesting some form of public statement in support of Le Droit au vol. Would Hugo underwrite his vision of the future of flight? Hugo had after all had such aerial visions himself, describing the astonishing view of medieval Paris ‘as seen from the air’ in the second chapter of his great novel Notre-Dame de Paris, entitled ‘Paris à vol d’oiseau’ (‘A bird’s-eye view of Paris’).25 He had also recently featured in a flattering cartoon, published by the Journal amusant, showing him ascending heavenwards for earnest discussions with God, in a balloon marked ‘Mankind’.

Hugo was controversial because he was a declared republican enemy of the Second Empire and all its works. To prove his ‘eternal’ opposition he was living in self-imposed exile from France in his famous clifftop residence, Hauteville House, on what he called the ‘foam-lashed rock’ of Guernsey. This exile had only increased his huge public following and readership back in France. Hugo was himself a past-master of publicity. His was exactly the name that Nadar needed.

Hugo wrote back one of those letters addressed simply to ‘Nadar, Paris’.26 He congratulated Nadar on his personal bravery during his balloon adventures – ‘What courage, intrepidity, audacity!’ Le Géant was, certainly, a typically monstrous product of imperial flamboyance and exaggeration, but ‘the risk you took was magnificent! And the risk is the true example!’ He did not mention the risk run by Madame Nadar and the other passengers.

Hugo announced that he would willingly put on his ‘prophetic wings’ for his reckless old friend. The concept of Flight was democratic, it was progressive, it was ‘universal’. The long open Letter on Flight which followed was, in effect, the text of a brilliant popular tract specifically designed for Nadar to print and distribute under the auspices of L’Aéronaute. It was addressed, in a modest gesture typical of Hugo, ‘To the Whole World’.

Its theme was radical, and its grandstand manner was crafted to appeal to the broadest possible readership. Like a modern tabloid editor, Hugo skilfully invented catchy slogans, coined neat catchphrases, and spun sensational headlines. His letter became a publicity brochure, a masterly piece of advertising copy for the art and science of flying. As he put it: ‘Let us deliver mankind from the ancient, universal tyranny! What ancient, universal tyranny, you cry. Why, the ancient, universal tyranny of gravity!’27

Hugo began on a patriotic note, recalling the self-sacrifice of all the previous French aeronauts, from Pilâtre de Rozier onwards. Ballooning was indeed a specifically French gift to the world, and no foreign aeronauts – not even Charles Green – were mentioned. It was the French who had opened a new world, a new direction of travel. Rousing phrases were piled one upon the other. ‘The iron bolt has been drawn back from the blue abysm.’ The ‘vertical journey’ had become possible. Mankind would take possession of the ‘fourth of the ancient elements’, and be ‘master of the upper air’. Man would be a bird, an eagle, a ‘thinking Eagle with a Soul’.28

It was the heroic Nadar, wrote Hugo, who had conclusively demonstrated that the aerostat, the ‘lighter than air’ machine, could never fulfil the immense promise of flight. The terrible crash of the Géant in Hanover had proved once and for all that the aerostat was fundamentally flawed as a concept.

Today the balloon has been judged, and found wanting … To be torn from the ground like a dead leaf, to be swept along helplessly in a whirlwind, this is not true flying. And how do we achieve true flight? With wings!…For the dream of flight to become the fact of aviation, we have only to accomplish a small and relatively simple technical break-through: to construct the first true ship of the air [le premier navire]…

Whoever you are, reading this declaration, lift up your heads! What do you see above you? You see clouds and you see birds. Well then, these are the two fundamental systems of aviation in operation. The choice is right in front of your eyes. The cloud is the balloon. The bird is – the helicopter!29

The idea of the helicopter or ‘helice’, as proposed by Hugo, was taken from both Nadar and Verne writing in L’Aéronaute. It was an idea gaining wide acceptance in the 1860s. Hugo popularised the fundamental distinction between the floating balloon (the cloud) and the driven airship (the bird). But how was the airship to be driven? How would its wings actually work? One solution was some form of spinning ‘airscrew’ or ‘propeller’ powered by an aerial engine. Like wings, but far more efficiently, the angled blades or paddles of such a device would have purchase on the air, and would drive or drag the craft through it, exactly like a marine propeller driving a ship through water. One possible design was Ponton’s ‘helicopter’, photographed by Nadar in 1863.

illustration credit ill.108

The two airscrews were apparently designed to produce both horizontal movement and vertical lift, though the parasol-parachute suggests some uncertainty about their efficacy. There is no indication of what engine might power this machine, but it clearly abandons the age-old chimera of ‘flapping’ wings, and is a step towards the propeller-powered ‘airship’.*

Navigable flight, continued Hugo in his Letter on Flight, would be of huge scientific and social importance once it was achieved. In praise of this hypothetical future, Hugo let out all his rhetorical sails:

It will bring the immediate, absolute, instantaneous, universal and perpetual abolition of all frontiers, everywhere … The old Gordian knot of gravity will finally be untied…Armies will vanish, and with them the horrors of war, the exploitation of nations, the subjugations of populations. It will bring an immense and totally peaceful revolution. It will bring a sudden golden dawn, a brisk flinging open of the ancient cage door of history, a flooding in of light. It will mean the liberation of all mankind.30

There was much more in this wild, heroic vein. The absurd error, or perhaps the glorious naïveté, of Hugo’s prophecies is striking. His vision of the ‘universal peace and freedom’ arising directly from the conquest of the air has a kind of innocence about it, which goes back historically to the ‘ballomania’ of the 1780s, and the declarations of poets like Erasmus Darwin and Percy Shelley. Yet perhaps we are now too quick to view these dreams of ‘liberating all mankind’ as entirely misplaced. The fact remains that air travel and transportation, as well as satellites, are the sine qua non of our global civilisation; and space flight may yet become the final means of its salvation. It would be interesting to read Hugo on the Apollo space missions of the 1960s, and the current Mars-landing programmes.

At any rate, Hugo now had the bit between his teeth. He unblushingly compared Nadar’s pioneering balloon flight to Hanover with Christopher Columbus’s sea voyage to discover America. Nadar’s public bravery – rather less obviously – was likened to the moral courage of Voltaire and the religious iconoclasm of Luther. If Nadar could be accused of self-promotion, of seeking publicity, of ‘making a noise’ with his balloon adventures, then so could those other master spirits. Yet they were each fighting for a worthy cause. With this thought, Hugo became fully airborne:

People accuse you, Nadar, of ‘just seeking to make a noise’. That is the age-old sneer! The sneer of silence against speech, dumbness against expression, castration against fecundity, nihilism against creativity, envy against the masterpiece, egoism against the generous act, the tin-whistle against the sounding horn, the abortion against the new born child … But I say the noise you make with Le Géant is A GOOD NOISE.31

illustration credit ill.109

Hugo closed his Letter on Flight on a more personal note, recalling a memorable exchange he had once had with the great French scientist François Arago (1786–1853). The outstanding astronomer and physicist of his generation, a staunch republican and a supporter of the earliest French scientific balloon ascents, Arago had died ten years previously, and was now widely regarded in France as something of a scientific visionary and secular saint. He had already been canonised by having craters on both the moon and Mars named after him, and was looked upon as a man who had seen the future.

According to Hugo’s story, the poet and the scientist were walking one evening in the Luxembourg Gardens, along the path known, symbolically enough, as l’allée de l’Observatoire. It had been an official festival day and public holiday, and they were deep in speculative discussion. A large balloon passed unexpectedly overhead, having just taken off from the Champ de Mars. Its full, round, pregnant shape, touched with gold by the setting sun, was ‘truly majestic’, and filled them both with a moment of silent awe.

I said to Arago: ‘There is the floating egg which is destined to become a bird! That bird is still inside the egg. But it will soon emerge!’ Arago seized me by both hands, and fixed me intently with his large, luminous eyes. ‘On that day,’ he murmured, ‘Geo will become Demos – the earth will belong to the People.’32

Hugo signed off with a final farewell to Nadar: ‘I no longer address you personally, brave Nadar the Aeronaut. There is nothing further I can tell you, that you do not already know. Instead, I fling this open letter upon the four winds. I write on its envelope: A tout le Monde!’33 As it turned out, Hugo was far from finished with balloons in 1865. The four winds would soon bring them back to him, as unexpected symbols of liberty, flying above the rooftops of Paris.

Over the next three years Nadar continued to send the repaired Géant around the cities of northern Europe, as much for tethered publicity displays as for actual flights. They were always accompanied by pamphlet copies of Hugo’s Letter on Flight and his own Droit au vol. Nadar even took the balloon to London, where it was exhibited at the Crystal Palace. The celebrated two-storey gondola was much photographed, and the cause of ‘heavier-than-air’ flight much discussed.

illustration credit ill.110

Balloons and flying became populist symbols again; the propaganda for aviation and republicanism were twinned. During these tours Nadar met many writers and opposition politicians, in exile like Hugo from the Second Empire. Among them were Charles Baudelaire and Armand Barbès, both in Brussels and both old friends from the Panthéon Nadar days. Nadar’s aeronautical fame gave him a certain freedom of manoeuvre. When he was presented to Leopold II, the King of the Belgians, the following exchange took place. His Majesty: ‘You are a republican I suppose, Monsieur Nadar?’ ‘Yes indeed, sire. And you?’ ‘Ah! Monsieur Nadar, my profession absolutely forbids it.’34 Even so, the king could not be persuaded to ascend in the republican balloon.

The end of the Géant itself was strangely muted. Perhaps this was appropriate for a balloon dedicated to advertising its own superannuation. The last three ascents of the now ancient and creaking campaigner, damaged as much by overland as by aerial travel, took place in Paris during the Exposition Universelle of 1867. Captained by Nadar, it was launched from Les Invalides, amid great celebrations and thousands of spectators, but got little further than the Paris suburbs.

A balloonist of the new generation, Wilfrid de Fonvielle (1824–1914), who was on board, left a wry account of ‘the three last gasps of the late, great Géant’.35 The old balloon appeared ‘striped like a zebra’, encircled by long bandages of white silk crudely sewn on with black thread to cover some of its ‘many wounds’. Fonvielle dreamed of going as far as the Danube, but finished up at Choisy-le Roi instead, and the balloon leaked alarmingly all the way. White smoke oozed from its top seams, ‘like the steam that issues from the funnel of a locomotive’. Someone joked that it was just the old Géant ‘smoking his pipe’, but it was no laughing matter to Fonvielle: ‘This pipe was being smoked over a barrel of gunpowder.’ It was a relief when the balloon was finally deflated, folded and bagged up. The whole extraordinary legend of Le Géant, so carefully built up by Nadar, seemed finally reduced to a large dirty sack of ‘so much matchwood’. Perhaps, Fonvielle concluded, it had rendered ‘some slight service to the art of aerostation’.36

* In fact the first true airship or dirigible had already been invented in France by the engineering genius Henri Giffard (1825–82). In September 1852, Giffard successfully flew his baguette-shaped hydrogen balloon with a three-horsepower steam engine slung beneath it, driving a ‘helice’, or propeller. It was steered with an upright rudder, and flew twenty-seven kilometres southwards from the Paris racecourse to Trappes. However, it was slow and clumsy, and would not fly against contrary winds. Hampered by lack of money to develop his ideas, and despite receiving the Légion d’Honneur in 1863, Giffard spent the rest of his career doggedly building bigger and bigger captive hydrogen balloons. With equal irony, his wonderful steam engines were used to power their cable winches on the ground. His final balloon was a true captive monster, a King Kong of the balloon world. In his late fifties Giffard’s eyesight began to fail, and, unable to contemplate a world without a visual horizon, he committed suicide. But his ideas influenced Charles Renard’s airship La France, which made its maiden flight in 1884; and later still, as we shall see, Salomon Andrée in the Arctic.

Yet the imaginative influence of Nadar’s gigantesque balloon, and the publicity surrounding it, was far more subtle and widespread than this. It elevated and transformed the very idea of travel itself. Jules Verne had been following Nadar’s adventures from the beginning, and in December 1863 published a long article in Musée des familles, ‘Nadar the Aeronaut’, praising his courage and vision. He said that Nadar was the man who had demonstrated that it was not enough merely to ‘float in the upper air’ passively. The true hero would actively ‘fly through it’ with purpose and energy, towards a definite destination. This destination could be a place, real or invented; or it could be ‘adventure’ itself.37

Jules Verne (1828–1905) had been an unknown freelance science journalist from Nantes when he first met Nadar in 1862. He was still struggling in his mid-thirties to establish his literary career in Paris, and had been supporting himself with miscellaneous legal work, writing plays, and publishing occasional short articles on travel and invention. For several years previously he had been looking for actual adventures, ‘true stories’, for his magazine articles. He slipped away ‘day and night’ from his job at the Paris Bourse to research at the Bibliothèque Nationale, which offered him ‘endless resources’.38

Verne saw that travel in general, and ballooning in particular, potentially supplied fantastically rich material. For instance, in 1849 a young French aeronaut, François Ardan, had made the first daring crossing of the Maritime Alps by balloon, starting at Marseille and landing near Turin.39 Verne did not forget Ardan’s name when he later came to invent his scientific daredevil ‘Michel Ardan’, who flies to the moon.

Verne had also researched Julien Turgau’s vivid study Les Ballons: Histoire de la locomotion aérienne, which had appeared in 1851. It had an inspired Introduction by the visionary poet Gérard de Nerval, and memorable steel engravings of airborne balloons. Equally, his friendship with François Arago’s younger brother, the seasoned travel writer Jacques Arago, turned him towards the idea of fantastic expeditions. Early results were his articles ‘A Balloon Trip’ (1851) and ‘Wintering on the Ice’ (1853). By the end of the decade he was already discussing with Alexandre Dumas fils his new concept for what he called ‘le roman de la science’.40

When Verne met Nadar and the editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel – another member of the Panthéon Nadar, and the hugely successful publisher of Balzac, Hugo and George Sand – in the autumn of 1862, the crucial moment had arrived. He abandoned a negative, dystopian novella about Paris, and agreed to write instead a high-spirited balloon adventure.* Verne wrote excitedly to his friends at the Bourse bidding them adieu, and putting his future in appropriately commercial terms. He was writing a novel ‘in a new style, truly my own – if it succeeds it will be a gold mine’.42 The contract for Cinq semaines en ballon was signed with Hetzel in October 1862.

In fact, a crude first version of the story had already appeared as an article in a Swedish magazine under the title ‘In a Hot-Air Balloon Over Africa’. It was never translated, and according to Verne’s wife he had struggled to expand it in a manuscript version with the working title ‘A Voyage Through the Air’. It caused him such despair that he had threatened to burn it.43

After many talks with Hetzel and Nadar, Verne rewrote and expanded the manuscript in his ‘new style’. Inspired by Nadar’s enthusiasm and Hetzel’s editorial skills, he transformed his flat documentary ‘magazine manner’ into a brisk form of narrative. His chapters became brief and punchy: there are forty-three in the short novel. He added a mass of realistic scientific details and dramatic ballooning incidents: storms, condors, elephants, volcanoes, drought, hallucinations, mirages, wild tribesmen, and of course frequent near-misses and crash-landings.

illustration credit ill.111

Above all he introduced a lively play of comic dialogue among his balloon crew. Verne saw that the balloon basket (like Ardan’s later moon rocket, or Captain Nemo’s submarine) was the ideal enclosed space in which to stage a drama, and draw out contrasting characters under pressure. As Nadar would experience, any balloon flight – especially a long one – was always essentially a piece of theatre. To exploit this Verne introduced three highly contrasted protagonists, and Hetzel soon appended a provocative subtitle: Five Weeks in a Balloon; A Voyage of Discoveries in Africa by Three Englishmen. The novel was swiftly completed and published in late January 1863, three months after Nadar’s ‘Manifesto’. It was the perfect moment: talk of ballooning and Le Géant was becoming all the rage.

* It is often forgotten that at this time Jules Verne still had profound doubts about scientific progress and technology. In this same year, 1862, he wrote the short dystopia entitled ‘Paris in the Twentieth Century’, about a young poet living in a world of skyscrapers, high-speed trains, gas-powered cars, chemical warfare and global telegraphy, where even the dead can be revived by electric shock treatment. Far from being happy, Michel Defrenoy is deeply depressed by the materialism of society; he can find no serious books or music, and he detests living off synthetic food made from coal. A new ice age engulfs the whole of Europe, and Michel dies in the snow outside Père Lachaise cemetery clutching an unpublished book of his poems entitled Hopes. When Verne presented the draft of this grim vision to Hetzel, he refused it: ‘Wait twenty years to publish this book. No one today will believe your prophecies, and no one will care about them – It will damage your reputation.’ Instead he persuaded Verne to turn to the balloon story. The manuscript was only recovered over a hundred years later, by Verne’s great-grandson, in 1989. It was finally published in 1994, and paradoxically, its pessimism rather enhanced Verne’s reputation.41

Five Weeks in a Balloon is Jules Verne’s first true science fiction novel, his first roman de la science. It proved to be the major breakthrough in his career as a popular author. With extraordinarily realistic details and statistics, it recounts a purely imaginary balloon expedition westwards across the whole of Africa, starting from the island of Zanzibar, in the Indian Ocean. Zanzibar, then a British colony, lies off the east coast of what is now Tanzania. The protagonists are three unflappable British types, an adventure formula that Verne would develop and repeat in many later books.

The first is the eccentric Dr Samuel Fergusson, dreamer and explorer, the commander of the expedition, ex-member of the Bengal Engineers, ‘possessed by the demon of discovery’. Florid-faced, calm, stoic, wiry, immune to any disease or privation, Dr Fergusson has ranged restlessly through India, Australia and America, and has ‘dreamed of fame like that of Mungo Park and Bruce, or even – I believe – like that of Selkirk and Robinson Crusoe’.44 For Fergusson the balloon is the application of pure science to exploration. He is the prototype of all Verne’s cerebral adventurers.

Next is his bluff and fearless friend Dick Kennedy, a big-game hunter and ‘a Scotsman in the full significance of the word, open, resolute, and dogged’. They had met in India where Kennedy ‘was hunting tigers and elephant and Fergusson was hunting plants and insects’. Kennedy is shrewd and practical, and thinks Fergusson’s African balloon project is obviously mad. But when he finds he cannot prevent it, he decides to join Kennedy out of blind loyalty. ‘ “Rely on me,” said Fergusson, “and let my motto be yours: Excelsior!” “Very well, old man, Excelsior!” answered the sportsman, who didn’t know a word of Latin.’45 Excelsior means, of course, Ever Higher!

Finally, as the catalyst between the two, Verne conjures up their small Cockney manservant, Joe. In recognition of Victorian class distinctions, Joe has no surname, but he is far from being a cypher in the plot, or mere ballast in the balloon. (Indeed, he is the forerunner of Passepartout in Around the World in Eighty Days.) Smart, resourceful, quick-thinking and sharp-tongued, he is also a formidable gymnast, and so perfectly adapted to life in a balloon basket: ‘Jumping, climbing, somersaulting, performing a thousand impossible acrobatic tricks, were child’s play to him.’ More than this, he is one of Nature’s enthusiasts: fascinated by science, in love with balloons (‘beautiful things’), and above all loyal to his master: ‘If Fergusson was the brilliant brain of the expedition, Kennedy was the brawny arm, and Joe was the dexterous hand.’46

The novel opens with a remarkably convincing account of Dr Fergusson being summoned before the Royal Geographical Society in London, from whom he hopes to raise funds. However, satirical elements soon surface. Verne hints at his wide background reading by making disguised reference to Poe’s balloon hoax story of nearly twenty years previously:

‘Perhaps this incredible scheme is only intended to hoax us,’ said an apoplectic old Commodore. ‘What if Dr Fergusson didn’t really exist?’ cried another malicious voice. ‘Then he’d have to be invented,’ replied a waggish member of this learned Society. ‘Show Dr Fergusson in,’ said Sir Francis simply. And the doctor entered amid a thunder of applause, and without the least show of emotion … His whole person exhaled calm gravity, and it would never have occurred to anyone that he could be the instrument of the most innocent hoax.47

Verne then presents the mass of historical, scientific and statistical data that he was learning to deploy, sometimes quite mischievously, in order to provide the necessary frame of realism. Chapter 4 is a short history of African exploration, from Bruce to Speke; Chapter 7 a short treatise on balloon theory and practical navigation by east-to-west trade winds (which John Wise would have recognised). Some of it is straight-facedly pedagogical in tone: ‘By giving the balloon a capacity of 44,847 cubic feet and inflating it not with air but with hydrogen which is fourteen and a half times lighter than air and weighs only 270lbs, a change of equilibrium is produced amounting to a difference of 3,780 lbs, which constitutes the lifting force of the balloon.’48

Other sections slip into pure romance, as when Dr Fergusson harangues Kennedy on the beauty and convenience of balloon flight. Here one can hear the voice of the authentic balloon geek. It is a voice partly inspired by Nadar, but also going back to the very roots of the aeronautical tradition and eighteenth-century ballomania.

I don’t intend to stop until I reach the West coast of Africa! With my balloon there will be nothing to fear from either heat, torrents, storms, the simoon, unhealthy climate, wild animals or savage men. If I’m too hot, I go up. If I’m too cold, I come down. If I meet an impassable mountain, I fly above it; a precipice, I sail over it; a river, I float across it. If I encounter a storm, I ascend above it; a torrent, I flit over it like a bird. I travel without fatigue and halt without need of rest. I soar over new cities. I fly with the swiftness of a hurricane. Sometimes I rise to the very edges of the breathable atmosphere. At others, I descend to skim over the earth at a few hundred feet, so the great map of Africa unwinds beneath my eyes like the mightiest atlas in the world.49

Launched from Zanzibar, they do indeed follow ‘the great map of Africa’ along the westward line of the upper Nile into the African interior. But nothing goes as Fergusson had prognosticated. The picaresque adventures and mishaps of their balloon, the Victoria, unfold one after another, helter-skelter, practically without pause for breath – or hydrogen. Verne, brilliantly inventive and bold in his plotline, gives a new meaning to the term suspense. The crew suffer from fever, are towed by a runaway elephant, attacked by condors, worshipped by witchdoctors (who think they are the moon come to earth). They rescue a missionary from cannibals, sail through a hail shower, survive a huge electrical storm, overfly an active volcano, escape from clouds of locusts, beat off ‘incendiary pigeons’, and find the source of the Nile, though not necessarily in that order. In the end, with no more hydrogen left, they turn the Victoria into a Montgolfier. By burning dry grass beneath the canopy, they just manage to escape the final wave of ‘infuriated natives’, and skim across a river into French-occupied Senegal and safety.

Infuriated natives in fact feature regularly throughout the novel. Long before, Shelley had imagined that ‘the shadow of the first balloon’ crossing Africa would be an instrument of liberation and enlightenment. But for Verne the balloon is more a symbol of imperial command, and scientific superiority.* Cinque semaines is paradoxically a work of colonial exploitation, as much as exploration. It is blatantly – almost naïvely – racist throughout, and observations such as ‘Africans are as imitative as monkeys’ occur regularly throughout the story.51

Balloon height gives the crew not only safety, but also moral superiority. To them, tribesmen are savages, and the wildlife – the elephant, the blue antelope – is there largely for big-game hunting. De haut en bas gains a literal force. Africa, and Africans, can become just ‘scenery’. It is the recognisable beginnings of a safari culture. Yet it is perhaps also relevant that this is a Frenchman writing about British imperialists, and their very balloon is named after their Queen.

The Victoria passed close to a village which the doctor recognised from the map as Faole. The whole population had turned out, and howled with rage and fear. Arrows were vainly shot at the monster of the air soaring majestically above all this impotent fury. The wind was blowing them south, but this did not worry the doctor, as it would enable him to follow the route taken by Captains Burton and Speke. Kennedy had now become as talkative as Joe. ‘A bit better than travelling by coach,’ he observed. ‘Or by steamer,’ replied Joe. ‘I don’t know I think much of railways, either,’ continued Kennedy. ‘I like to see where I’m going.’ ‘Balloons is priceless,’ agreed Joe. ‘You don’t feel you’re moving at all – the scenery just slides under you. Just begging to be gawped at!’ ‘Yes, a splendid view! Like dreaming in a hammock.’ ‘What about some lunch, sir?’ said Joe.52

Nevertheless, by using the balloon to open up a new, exotic world – with its special geography, anthropology, natural history, geology and climate – to a popular readership, Verne had a surprise best-seller on his hands. The book was quickly translated throughout Europe, and Verne was able to follow it up with astonishing rapidity. He had found his path, and from that point on he published two or more books a year for the next decade.

It was an amazing output. The most successful titles became equally celebrated in English as in French (and eventually as films). They included Voyage au centre de la terre (Journey to the Centre of the Earth, 1864); De la terre à la lune (From the Earth to the Moon, 1865); Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, 1869); and Le Tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours (Around the World in Eighty Days, 1872). Hetzel quickly saw the enormous potential of the series and began to publish it collectively as Voyages Extraordinaires (Astonishing Voyages). From then on Verne could live on his writings, and his reputation was made.

illustration credit ill.112

Verne continued to work for Nadar’s Society for the Promotion of Heavier than Air Locomotion, of which he eventually became Secretary. He also immediately repaid his fictional debt to Edgar Allan Poe, by publishing a short study, Edgar Poe et ses oeuvres, in 1864. He had, after all, trumped Poe by producing probably the most famous of all imaginary balloon flights of the nineteenth century, to which he later appended his Pacific balloon story The Mysterious Island, of 1875. Yet the novel is in a sense uncharacteristic of the rest of Verne’s romans de la science. Like its successors, it is wonderfully inventive in its picaresque storyline, and it is obvious why Hetzel had such confidence in his author’s power to produce incident-packed narrative.

Yet it contains very little scientific or technological prophecy. It is not a ‘futuristic’ novel. The journey of the Victoria, just like that of Le Géant, is presented as a contemporary marvel, almost as an extended news item, and is specifically described as ‘the most noteworthy expedition of the year 1862’.53 It is true that Dr Fergusson also has various invented devices for increasing the balloon’s lifting power (such as a ‘Bunsen battery’ burner for raising the temperature of the hydrogen – a glimpse of the prototype propane balloons of the 1960s). But he also takes every opportunity to expatiate on the advantages of ‘modern’ flight over traditional land-based transport in the tropics. If, for example, they had attempted to travel overland like Mungo Park or Speke, they would have been overcome by disaster:

‘Since leaving Zanzibar half our pack animals would have died of fatigue. We should be looking like ghosts and feeling desperate. We should have had constant struggles with our guides and porters, and no protection against their savagery. We would have suffered the humid, unbearable, disabling heat by day; and often intolerable cold by night. We would have been bitten by insects with mandibles capable of piercing the thickest canvas and driving men mad. Not to mention the wild animals and savage tribes …’ ‘I’m in no hurry to try it,’ remarked Joe.34

There is a premonition of future imperial romances, and the Lost World genre, especially of the British Boy’s Own type – Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and She (1887) are both set in Africa. But Verne’s sense of authentic reportage remains strong. The novel closes on a deliberately dry, factual note: ‘The chief result of Dr Fergusson’s balloon expedition was to confirm in the most precise manner the geographical facts and surveys reported by Bath, Burton, Speke and others … Thanks to the present expeditions undertaken by Speke and Grant, we may before long be able to check in their turn the discoveries made by Dr Fergusson in that vast area lying between the 14th and 33rd meridians.’55 Verne cannot quite forbear to add another, more mischievous statistic: that a special edition of the London Daily Telegraph covering the balloon story ‘sold out 977,000 copies’ on the day of publication.

In consequence, one of the most striking things about the novel’s enthusiastic reception was that many reviewers thought it might actually be a true story. With widespread knowledge of balloon adventures like those of Green, Godard and Nadar, an aerial safari over darkest Africa did not seem intrinsically unlikely. Verne might be writing non-fiction. The reviewer in the new Paris daily Le Figaro played elegantly with this idea: ‘Is Dr Fergusson’s journey a reality or is it not? All we can say is that it is as bewitching as a novel and as instructive as a book of science. Never have the serious discoveries of celebrated travellers been summed up as well.’†

* It is instructive, and poignant, to compare this with Percy Shelley’s views some fifty years earlier: ‘The balloon promises prodigious faculties for locomotion, and will allow us to traverse vast tracts with ease and rapidity, and to explore unknown countries without difficulty. Why are we so ignorant of the interior of Africa? – Why do we not despatch intrepid aeronauts to cross it in every direction, and to survey the whole peninsula in a few weeks? The shadow of the first balloon, which a vertical sun would project precisely underneath it, as it glided over that hitherto unhappy country, would virtually emancipate every slave, and would annihilate slavery forever.’50

† As so often with ballooning, the boundaries between fact and fiction remain curiously porous. In summer 1962, a real balloon voyage across Africa, starting from Zanzibar, was undertaken by three Englishmen to celebrate the centenary of Verne’s Five Weeks. The story is told in Anthony Smith’s delightful balloon classic Throw Out Two Hands (1963). (The title refers to the tiny amounts of sand ballast required to adjust the equilibrium of a hydrogen balloon.) The modern trip was presented as an African safari from the air, with great attention paid to wildlife and conservation. One of its notable feats was to overfly the Ngorongoro crater, though unlike Verne’s volcano, this was not erupting at the time. As the expedition was partly sponsored by the Sunday Telegraph, Smith and his amiable camera crew, Douglas Botting and Alan Root, had considerable technical back-up, and were only too grateful to rely on the help of local tribesmen, rather than fighting them. The style of the book might be described as post-colonial jovial. The balloon itself is christened Jambo, and ballooning is presented as an eccentric European sport, whimsical rather than imperial in its manner. The next year Smith became the first Briton (following Nadar’s avatar Michel Ardan) to cross the central Alps in a balloon.

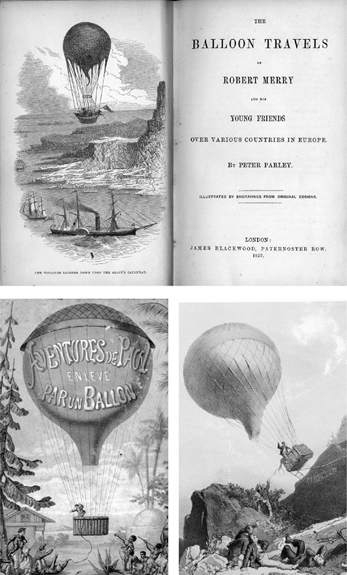

The idea that an ‘astonishing voyage’ might be instructive, or frankly educational, was already in the air by the 1860s. Hetzel considered Verne’s readership was primarily mass-market and adult, but this profile would soon alter. The later editions of Les Voyages Extraordinaires were more and more lavishly illustrated, which indicates that they were intended for an increasingly youthful audience. This was particularly true of Cinque semaines en ballon, which joined a flourishing new genre of educational children’s books, using the balloon as a pedagogic device. These had begun appearing, both in France and England, in the 1850s. The balloon, with its bird’s-eye or ‘panoptic’ view, its 360-degree tour d’horizon, and its ability to take its passengers across a huge variety of landscapes, became an instrument of, or even a metaphor for, encyclopaedic knowledge. In the right hands, Education itself could be presented as a kind of magic balloon journey.

One of the earliest attempts to do so was an American illustrated geography book, The Balloon Travels of Robert Merry and his Young Friends (1857). This was written by the prolific children’s author Peter Parley, as part of a series of educational adventures promoted by the Boston magazine The Robert Merry Museum. ‘Peter Parley’ was in fact the pseudonym of Samuel Griswold Goodrich (1793–1860), who liked to be known as ‘the Pied Piper in Print’. He claimed to be the author or editor of 170 volumes, with total sales of seven million copies. His series, beginning as far back as 1827, embraced geography, biography, history, science and miscellaneous tales. In 1851 Goodrich – or Parley – became American consul in Paris, and adapted many of his books for French children, a development that did not escape Hetzel.

illustration credit ill.113

The Balloon Travels, written towards the end of Goodrich’s career, was a kind of farewell to his young readers. It recounts a stately geographical sightseeing tour around the countries of Europe, each site illustrated by an aerial engraving. The frontispiece shows the balloon hanging dramatically over the famous Giant’s Causeway, an extraordinary outcrop of basalt rock columns on the coast of County Antrim, in Northern Ireland. The young travellers learn that its legends connect it to Fingal’s Cave in Scotland, and this kind of ‘aerial perspective’ gives them a new view of both history and geology.

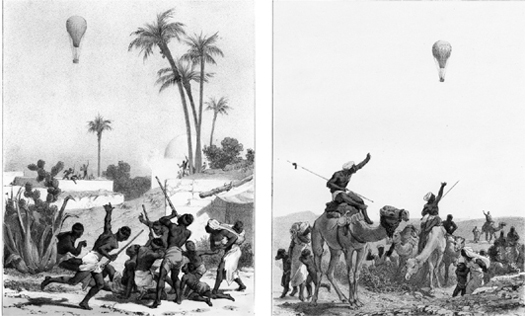

In 1869 came a much racier French book, Jean Bruno’s Les Aventures de Paul enlevé par un ballon – ‘The Adventures of Paul Kidnapped by a Balloon’. It was also remarkable both for its twelve beautiful illustrations (the originals in watercolour) and its naïve imperial attitudes. Paul’s epic flight begins by chance one summer in southern France. He accidentally falls into the basket of a giant French balloon, the Leviathan, while its three adult aeronauts are on the ground, attempting to anchor it. In a dramatic picture, we see the balloon caught by a gust of wind, the aeronauts sent sprawling, the anchor ropes snapping free, and Paul sailing away over a hillside. Soon the balloon crosses the Mediterranean, and takes him over Algeria and North Africa.

illustration credit ill.114

Paul is subsequently swept helter-skelter right across the varied landscapes of Africa. He watches fascinated as its jungles and deserts and savannahs pass beneath him. He encounters storms, wild animals, and wilder tribesmen. Some greet him with friendly waves, others shout and threaten him with spears. One picture shows enraged natives hurling weapons at the balloon overhead, with the caption ‘Paul could judge from this specimen of their behaviour what kind of greeting he could expect if he landed.’

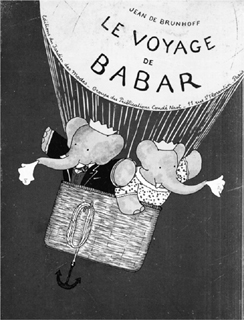

Such imperial balloon adventures remained popular throughout the nineteenth century. When Mark Twain brought Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer over to visit Europe in 1894, a chaotic journey in an airship forms the main thread of Tom Sawyer Abroad, and appears on the striking scarlet cover design. In fact this seems like Twain’s deliberate parody of Verne, as the balloon is piloted by a lunatic professor who insists on taking them to Africa: ‘He said he would sail his balloon around the globe, just to show what he could do.’ This vogue for imperial balloon voyages, launched by Verne, only concluded seventy years later with Jean de Brunhoff’s unforgettable Le Voyage de Babar (1932). In a gentle reproach to Verne, Brunhoff cleverly reverses the imperial perspective from the balloon basket. These native balloonists start from their home in Africa, and fly off to explore the wild boulevards of France. They are two charming and aristocratic jungle elephants (the young King Babar and his bride Celeste), who sail away in a bright-yellow balloon to spend their honeymoon shopping in Paris. This is a truly astonishing voyage.*

illustration credit ill.115

* The motif of the small boy carried away by a runaway balloon is so frequent in balloon history that it has almost reached the status of a myth to rival Icarus. Most recently a boy was carried off in a home-made balloon from a farm in Colorado in 2009; though significantly this later turned out to be a hoax perpetrated by his father. Ian McEwan makes memorable use of the runaway balloon in Chapter 1 of Enduring Love (1997), where it becomes a symbol of fatality, or fatal attraction, which brilliantly predicts the themes of his entire novel. The forces at work have a kind of ‘geometrical’ inevitability, in both physics and psychology. The fate of John Logan, lifted off his feet into the air when he gallantly tries to save the boy, and subsequently dropping to his death, is a bad case of falling upwards, which leaves the witnesses racked with guilt, while the small boy himself eventually floats back to earth quite unharmed. McEwan reflects further, and mordantly, on the fatal nature of balloons in his Introduction to At the Mercy of the Winds, by David Hempleman-Adams (2001). It is clear that, like Charles Dickens before him, McEwan profoundly distrusts them, even as instruments of the imagination, and possibly for similar reasons. The result is one of the most haunting opening chapters in contemporary fiction.