When Camille Flammarion had looked over his beloved France in June 1867, from 10,287 feet above the river Loire, he had seen a clear, sunlit horizon, with no remote stormclouds gathering to the east. Yet this was precisely the year in which the fifty-two-year-old Otto von Bismarck was appointed Prussian Chancellor, and became the driving wind of European politics. Far below, political events began moving with sinister inevitability. Beyond the river Moselle, in the borderlands of Strasbourg and Metz – borders invisible to balloonists – the newly founded North German Confederation was flexing its demographic muscles. Arcane diplomatic disputes, like the Hohenzollern candidature for the Spanish throne in 1868, produced a ping-pong of diplomatic insults between France and Prussia. They culminated in the deliberately provocative Ems telegram of July 1870, described by Bismarck as ‘my red rag to the Gallic bull’.

In August 1870 the Emperor Napoleon III, confident of the strength of his three enormous armies, had marched eastwards across the Moselle and the Meurthe with the intention of claiming disputed territories beyond Alsace-Lorraine. Arrogantly, almost casually, he declared war on the fledgling Prussian state, ignoring the fact that this was precisely what Bismarck desired in order to unite a new German empire. Napoleon was also ill-informed about the small but highly efficient Prussian armies, equipped with superb Krupp weapons, well practised at mobilising by train, and commanded by the brilliant strategist General Helmuth von Moltke.

The shock military defeat of the French First Army took place on 2 September 1870 at Sedan, in the Ardennes, where – almost unbelievably - the Emperor was captured. The Second Army retreated to Metz, where it was effectively blockaded. The remaining Third Army gallantly attempted to fight a rearguard action, retreating grimly westwards down the Loire. Some took their stand in Paris, others melted away westwards to fight again another day. These swiftly unfolding events were accompanied by the ignominious abdication of the Emperor Napoleon, whom Bismarck despatched politely to exile in England. On 4 September the Third Republic was declared under the republican politician Jules Favre, who had opposed the war. While some patriotic leaders, notably Léon Gambetta, remained in the capital, the official seat of government fled south-westwards, first settling in Tours on the Loire, and eventually in Bordeaux. Bismarck attempted to negotiate an armistice, but was refused, and proceeded to invade France at high speed, the first example of a true German blitzkrieg.

Accordingly, the Prussian 2nd and 3rd Armies under von Moltke contemptuously left the remaining French forces besieged in Metz, under the vacillating Marshal McMahon, and advanced steadily westwards towards Paris, along the lines of the Meuse and the Marne. The Prussian invaders split into a classic pincer movement, and by 10 September were pressing on the northern and southern suburbs of the city, halting only at the ring of isolated forts surrounding it. For the Parisians the air was full of the sound of approaching guns and the smell of burning.

Gaston Tissandier described the desperate rush of people from the surrounding countryside into Paris, with piled handcarts, aged relatives in wheelchairs, and scampering animals led on lengths of rope. He watched them hurrying through the city’s gates and ramparts ‘like a Biblical scene from the Flight into Egypt’.1 With terrifying speed and efficiency, the Prussians had virtually surrounded Paris in less than a fortnight, by 15 September 1870. Bismarck, a master of both strategy and symbolism, ordered the occupation of Versailles, and installed heavy artillery in preparation for shelling the city into submission.

European, and notably British, opinion was initially sympathetic to the Prussians, since it was the French who had declared war, first invaded at Saarbrücken, and then refused Bismarck’s offer of an armistice. The celebrated British war correspondent, William Russell of The Times, who had famously covered the Crimean War, significantly chose to report from the Prussian headquarters. This, for him, was the story his British readership wanted.

It was strategically important to Bismarck to retain this sympathy. The French under Napoleon III were regarded as foolish aggressors, and Paris under the Empire was widely viewed as the seat of fashion, frivolity and sexual licence, quite incapable of offering any resistance to an invader. It was a lax city of ‘luxury and pleasure’, as The Times put it with a certain relish. The newspaper’s Special Correspondent sent a dramatic despatch datelined Palace of Versailles, 30 September 1870, which opened: ‘Here at 7.30 p.m. the German Crown Prince and his Staff are comfortably quartered … close at hand they have an angry Paris agitated by a hundred passions … impotent in her rage and fierce vindictiveness.’2

In fact many pro-republican French people themselves felt ashamed of what France had become. Félix Nadar and Fonvielle both expressed such views. Victor Hugo, who had remained in exile since 1851, returned to Paris on 5 September, immediately the Third Republic was declared. He brought with him his new book of poems, symbolically entitled Les Châtiments. It meant, literally, ‘The Punishments’; or perhaps, ‘The Reckoning’.

Bismarck’s strategy was to take advantage of these international views, and avoid any direct military attack on the civilian population of Paris, who, as he put it bluntly, could ‘stew in their own juice’.3 Moltke contented himself with shelling the ring of huge, isolated forts – like Mont-Valérien and the Fort d’Issy – that surrounded the city, a psychological as much as a military tactic. The master plan was to close down all communication between Paris and the outside world. The Prussians intended to silence, humiliate and punish Paris – but to do it largely in secret. Without too much fuss, they would quietly starve her citizens into submission within a matter of weeks. It was therefore vitally important that the minimum information about actual conditions in Paris should be allowed to filter out, and that the French government should remain paralysed. The blockade was a military necessity, but even more a diplomatic one.

On 17 September a Times editorial noted grimly: ‘In a few days we shall know nothing of what is passing in Paris … The Prussian army is large enough to destroy regular and effective communication between the invested city and the rest of France … Will the whole body politic be paralysed?’ Nonetheless, the commentator remarked, it was possible that ‘Paris will show fight’.4

Click here to view larger image

It is difficult to imagine how complete such a blockade could be, in an age before electronic communications were universally established (let alone before radio, mobile phones or the internet). All the French telegraph lines were above-ground, and were easily identified and severed. In a matter of days, all roads were closed, all bridges were blown up or guarded, all railway lines cut, and all river traffic on the Seine strictly controlled. Even the smallest skiffs were caught in Prussian nets. There was a desperate last-minute attempt to lay a submerged telegraph line along the bed of the Seine from Paris to Rouen. This was hastily imported from England at vast expense in the last days of August, but within a week of its arrival the Prussians had discovered and destroyed it, its position betrayed by a French collaborator.5

One young British journalist daringly slipped into the city at the last moment, the bilingual Henry Labouchère of the Daily News. His last despatch noted that he had no idea how he could send his next one, and that he would keep a Diary of a Besieged Resident instead. For the moment Labouchère observed only a phoney war: ‘The cafés are crowded … In the Champs-Elysées the nursery maids are flirting with the soldiers … there is universal drilling by the militia … at the Rond-Point an exceptionally tall woman was mobbed because she was thought to be an Uhlan [Prussian dragoon] in disguise … but no one took it seriously.’6

But things soon became very serious. On 19 September the last telegraph line was cut, and the official Paris mail coach was turned back with a contemptuous volley of shots by the Prussian pickets. Twenty-eight postal runners were sent out the following day, but all except one were captured or shot.7 Every village in the Ile de France surrounding Paris, within a distance of some thirty miles, was either permanently occupied by troops or regularly swept by the Prussian cavalry, the dreaded Uhlans. The Prussian encirclement was complete, and the siege was now absolute.

It was expected to last a matter of weeks, and would certainly be – like all wars – ‘over by Christmas’. In fact it lasted for five increasingly agonised months. Two and a half million people were crowded and sequestered within the walls of Paris. As Gaston Tissandier wrote in the Magasin pittoresque: ‘Our mighty capital city was surrounded, cut off not only from France but from the entire outside world … Two million human beings were shut away, silenced, and fenced in by a bristling ring of bayonets.’8

The siege tightened its grip in early October. The Prussians began a ceaseless shelling of the twelve Paris forts from the surrounding heights, the regular booming explosions wearing away at nerves, and making nights sleepless. On 13 October, when the French gunners of Mont-Valérien tried to fire a salvo at a Prussian encampment, they inadvertently scored a direct hit on the beautiful palace at Saint-Cloud and flattened it. Paris seemed to be collaborating in its own destruction.

City life became constrained, pinched and, above all, cold. One by one the theatres were closed, the street gaslights were dimmed or extinguished after 10 p.m., horse-drawn cabs virtually disappeared from the boulevards. Well before dawn, all the bakeries were thronged by endless queues. Makeshift ration books were issued, covering milk, coffee, bread and sugar. Meat was rationed to thirty-five grams – slightly over an ounce – per head per day. All luxury goods, including candles, became rare, or very expensive. Most of the trees in the Bois de Boulogne were cut down for firewood. The bitter comment went round that Paris was still a beautiful woman, but she had shaved her head in penitence.

Most of the cafés remained open, and wine alone remained surprisingly cheap and plentiful: many of the poor, especially the soldiers, were drunk for much of the time. As food supplies became seriously short, most domestic animals in the city were eventually eaten, except for a few prudent cats. There was a cull of ducks, carp and goldfish from the municipal ponds. Over forty thousand horses, and most of the rare animals from the zoo at the Jardin des Plantes, including two elephants and two zebras, were butchered.9 A surviving restaurant siege menu proposes elephant soup, kangaroo stew, roast camel, antelope terrine, and baked cat with rat garnish.

By December, the poet Théophile Gautier found himself writing a tragic appeal to the municipal authorities on behalf of his horse. This horse, a family friend and a faithful old servant, ‘a poor and perfectly innocent being’, was due to be forcibly dragged off to the city abattoir in the next twenty-four hours. His appeal, beautifully phrased and genuinely touching, did not succeed. Finally, all inhibitions breaking down, there was a brisk trade in rats. In a later letter, Gautier remarked on the curious flavour of rat pâté.10

Hunger and humiliation were the chief Prussian weapons against the Parisians. There was a dangerous collapse of morale, and a mood of hopelessness and cynicism. The emergency government of Jules Favre seemed paralysed, and a Council of National Defence was formed. Metz surrendered. The French army and the National Guard, under General Trochu, did little more than hold parades along the empty boulevards. Despite the presence of thousands of National Guards, there was no immediate attempt at a breakout. When this did come, on 27 November, under the vainglorious General Ducrot (‘I will only return dead or victorious’), it was a catastrophic failure, costing more than twelve thousand lives (but not Ducrot’s).11 There was talk of setting up a revolutionary Commune, and on several occasions the Hôtel de Ville was surrounded by a hostile crowd, and General Trochu was threatened and barracked.

illustration credit ill.140

Above all, there was a growing sense of utter isolation. All communications with the outside world had been severed. No post, no despatches, no newspapers; no Reuters cables, no weather reports, no London stock exchange figures; no Italian magazines, no American scientific journals. Most demoralising of all was the crushing of ordinary private life. From beyond the steely Prussian lines there came no family letters, no news of grandchildren or aged parents, no cheering get-well postcards, and no lovers’ billets-doux. Paris, the centre of European civilisation and enlightenment, was psychologically shrunk and physically silenced, just as Bismarck had planned.

Worse than that, it was mocked. The Times summarised the situation: ‘The Germans have on their side all the organized apparatus of modern warfare, strong discipline, a unanimous will; while on the side of France there is wild fury, alternate fits of overweening confidence and blank despondency, no mutual faith, no truth, and a suicidal tendency to universal social dissolution.’ In the circumstances, The Times concluded icily, the immediate, peaceful and silent surrender of Paris to the Germans would be ‘a triumph of civilization’.12

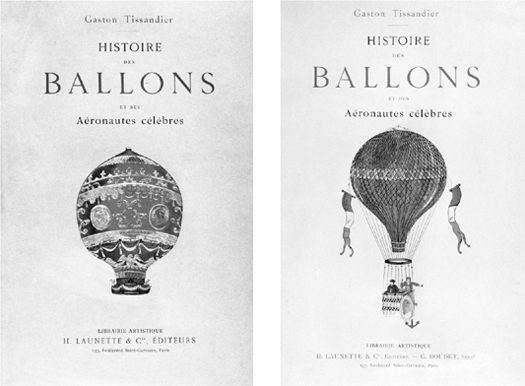

It was precisely at this low point of collapse and chaos that the fantastic story of the Paris siege balloons began. In the space of four months, between 23 September 1870 and 28 January 1871, no fewer than sixty-seven manned balloons were successfully launched from the encircled city, finding a new method of breaking a modern siege.13 In many ways these balloons represented the apotheosis of aerostation in the nineteenth century. They achieved what had never been done, or even fully imagined, before. Without being military balloons or carrying weapons, they changed the conditions of human warfare. They were the first successful civilian airlift in history.

Even as the Prussians advanced, the small group of aeronauts saw that there was one route out of the city that no one had really considered, and that remained unguarded: the air. The practical, and especially the propaganda, possibilities of balloons suddenly inspired them with a vision. Gaston Tissandier wrote a moving declaration on behalf of his band of brothers:

The silencing of Paris would be the death of France. Our besieged city would be lost irrevocably if she cannot find some way of making her voice heard abroad. Whatever the cost, we have to find a means of avoiding the slow torture of psychological encirclement [l’investement moral], as well as establishing communications with the army of the Loire. All ground routes being blocked, all river routes being barred, there remains but one other dimension open to the besieged – THE AIR! Paris will be reminded that balloons are one of the chief glories of the scientific genius of France. The mighty invention of Montgolfier is destined to come to the aid of la Patrie in this hour of mortal danger.14

This was all very fine. But initially there was no official response from the new Council of National Defence, or the harassed ministers of the Third Republic. Neither General Trochu’s army nor the Paris militia owned a single military balloon. The Minister for War, General le Flô, had his eyes fixed bleakly on the ground, desperately concentrating on supplying the Paris forts, and building up the city’s ramparts and artillery defences. Even the young and vigorous Minister for the Interior, Léon Gambetta (1838–82), the man of vision and energy, the hope of France, had no strategic policy on the air. There was plenty of coal gas in the enormous gasometers of La Villette and Vaugirard, but nothing to put it in.

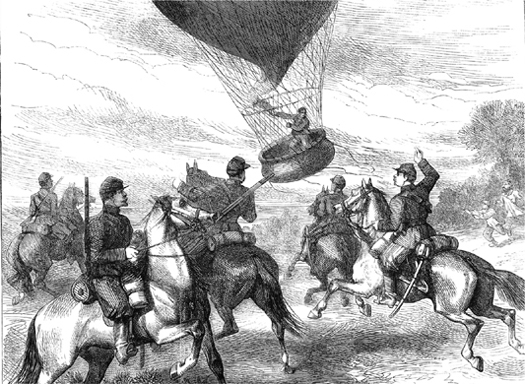

Besides, ballooning out of Paris was regarded as a high-risk, and probably suicidal strategy. No one knew if a balloon could escape the inevitable Prussian fusillade, and the legendary power of the new Krupp field guns. A balloon would pass with agonising slowness over the armed siege lines, more than sixty miles deep in many directions, and would doubtless be pursued by Prussian cavalry, the notorious Uhlans, in the spirit of a murderous fox hunt. Moreover, the Prussians had made it clear that anyone caught crossing the siege lines would be shot out of hand as a spy.

Equally, no one was sure which was the safest wind direction to try. The Prussians were known to be bivouacked in most of the towns and villages to the north and east of Paris, and out along the Marne as far as the newly occupied Alsace-Lorraine. To the south and west, where von Moltke had set up his headquarters at Versailles, approximately twelve miles from Paris, there were huge field garrisons and artillery supply dumps. Prussian cavalry units were constantly foraging and burning, and shifted quarters without warning. Officers had also forcibly requisitioned and, as it later emerged, looted and despoiled, many of the châteaux throughout the region, as far as Normandy. Moreover, the sympathies of the local farmers and peasantry could never be entirely relied upon.*

Finally, even if balloons were available, could actually fly out of Paris, and land safely, what exactly could they achieve? Clearly there was no question of using them to move troops en masse, as Benjamin Franklin and later Napoleon had once imagined. But might it be possible to establish communications with the Army of the Loire? Or to make contact with members of the government in exile at Tours, nearly a hundred miles to the west? Beyond these purely military considerations were other tantalising possibilities: could they deliver news despatches, a civilian postal service, or even some form of propaganda campaign?

Just four balloons were ready in Paris in September 1870. All were in private ownership, and most were rather the worse for wear. The first was the Neptune, the same balloon that had flown out of Calais in the storm, still manned and owned by Jules Duruof, now twenty-nine. The second was Les Etats-Unis, owned by the Godard family, and piloted by the comparative veteran Louis Godard, though he was still aged only forty-one. The third was Le Céleste, the scientific balloon now owned by Gaston Tissandier, aged twenty-seven. The fourth was Le National, lent by the Godards but piloted by Albert Tissandier, aged thirty-one. But the man who largely organised the whole initiative was none other than Félix Nadar.

* The ambiguous aspects of the Prussian occupation, and the issue of collaboration, were savagely portrayed by Guy de Maupassant, who fought against the advancing Prussians as a twenty-year-old volunteer, and later wrote a number of short stories based on his experiences. ‘Mademoiselle Fifi’ (1882) has a typically ironic title, which is the nickname of a particularly sadistic Prussian officer. While entertaining willing French girls from the local village, he destroys the beautiful interior of his château billet, out of a mixture of contempt and brutal drunkenness. In ‘Boule de Suife’ (‘The Suet Dumpling’, 1880), a fat, kindly French prostitute is forced to sleep with a Prussian officer for the convenience of her fellow coach passengers. This happens in Normandy, near Rouen, over sixty miles from Paris. Maupassant’s most moving reflection on the times appears in ‘Two Friends’ (1882). Two Parisians, driven by the hunger and boredom of the siege, get a little tipsy together on cheap wine, and set off for an innocent afternoon’s angling on the lower reaches of the Seine, near the Fort Mont-Valérien. They inadvertently cross into no-man’s land (hauntingly described), and after a few minutes’ idyllic fishing, are captured by a Prussian patrol. They are cross-questioned, skilfully tempted to betray each other by revealing a password, and when this fails, casually shot as spies. Their bodies are thrown unceremoniously into the Seine, while their little catch of fish, still leaping and gleaming in the late sunshine, is symbolically emptied from the Parisians’ net into the Prussian stockpot.

It was done with all Nadar’s characteristic panache and flair for publicity. Within a week of the outbreak of war, he had created, virtually out of nothing except a piece of headed notepaper, the ‘No. 1 Compagnie des Aérostiers’ – The Number One Company of Balloonists. Starting with Jules Duruof and his balloon the Neptune, he began enthusiastically recruiting among his friends, and anyone who had known Le Géant. At the same time he wrote directly to the Council announcing that he was setting up, on his own initiative, an observation-balloon service on the heights at Montmartre. From here his No. 1 Aérostiers (still basically himself and Duruof) would guard the northern approaches to the city by day, and by night mount high-powered electric searchlights, adapted from arc lights from his photographic studio.

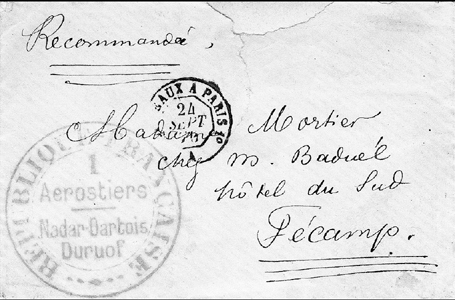

By 8 September 1870 Nadar had established a camp on the place Saint-Pierre, in the north Paris district of Montmartre. Besides Duruof, nine other balloonists had rallied to his call, including the Parisian balloon-maker Camille Dartois, the mechanical engineer Eugène Farcot, the doctor Emile Lacaze, and the militant socialist Jean-Pierre Nadal, who would go on to become Directeur Aéronautique for the Paris Commune during the tragic uprising of 1871. Apart from three bell tents and the tethered Neptune, Nadar’s main equipment consisted of a supply of headed notepaper, and a fine metal stamp with the company’s logo on it: ‘République Français; No. 1. Compagnie des Aérostiers. Nadar-Dartois-Duruof’.15

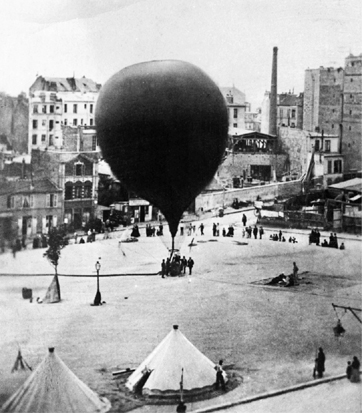

The place Saint-Pierre was an ideal balloon site, both strategically and psychologically. It was a flat platform of open wasteground, three hundred feet below the Butte Montmartre. A pagoda-like monument known as the Solferino Tower dominated the northern ridge of the Butte, and a steep bank of tussocky grass on which goats grazed and ragamuffin Parisian children played led down to Nadar’s encampment below on the Place. From the top of the Butte, the highest point in the whole of Paris, one could look north as far as the little villages of Saint-Denis and Le Bourget, now occupied by the Prussians.

illustration credit ill.141

In the opposite direction there was an unobstructed view from the Butte southwards, over the rooftops of Paris towards Montparnasse. All the heart-stirring monuments of the city were laid out for contemplation. The Aérostiers could see, in a single great panoramic sweep from left to right, the Vendôme column, the towers of Notre Dame, the dome of the Panthéon, the spires of the Institut, the green copper roof of La Madeleine, and the glittering golden cupola of Les Invalides. It was a place from which a patriot could see what he was fighting for.*

Nadar began his observational ascents in the tethered Neptune on 16 September, going up six times by day and three times by night. He had small cards printed off for his observation notes. These showed an outline map of Paris upon which he marked in all the military dispositions he could identify. To do this he used ‘naïve’ coloured crayons: ‘red for French, blue for Prussian, black for doubtful’. These cards he despatched ‘religiously’ to General Trochu, but never heard a word back in return.16

Nadar had established a simple rope cordon around the balloon site. Theoretically, this was to protect the Neptune, and the three bell tents where the Aérostiers team took turns to sleep and eat, from restive crowds. The weather had been cold and wet, and they had few provisions, but a local restaurateur known as Monsieur Charles provided them with cheap meals and wine. The patriotic young Mayor of Montmartre, future Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (only elected on 5 September), after objecting violently to their commandeering the Place without his permission, suddenly sent them a cartful of hay to sleep in. To this he added a gift of five or six large dogs to keep the area secure, and if necessary to warm their bell tents.17

The Prussian encirclement of the city was so complete that it was immediately clear that balloon observation was practically superfluous. It was now that Nadar began to consider the much more perilous possibility of actually crossing the siege lines. The following day, 17 September, he wrote urgently to Colonel Usquin, at the Council for the Defence of Paris: ‘Monsieur Cornu, whom we had the honour to see yesterday, spoke to us of the fabrication of free flight Aerostats, in the event that communications should be entirely cut. This concept is an excellent one, and all our personnel are immediately ready to volunteer for such missions, one after the other, as necessary.’18

He added, on a strictly practical note, that he only had one balloon, the Neptune, and that the Council should be aware that any new balloons would take him a minimum of two days to complete. However many specialists were employed, the canopies would always require ‘three separate coats of varnish’ to seal them, and each coat took at least twelve hours to dry properly.

Nadar’s historic proposal for launching a first ‘free flight’ balloon out of Paris produced absolutely no effect for several days. This left him and Jules Duruof in a fever of frustration. All the time they could see – and smell (‘insupportable stink of burning straw’) – from the observation position of the Neptune, four hundred feet above the Butte, that the Prussians were digging in and preparing their Krupp guns. They also knew that Louis and Jules Godard, based nearby at the La Villette gasworks, were making similar proposals to the Defence Council. As so often in war, there was growing rivalry between allies, as well as cooperation.

illustration credit ill.142

On 21 September, Monsieur Rampont-Lechin, the Director of Postal Services, finally issued a top-secret request to the Council for National Defence: ‘It has become absolutely necessary and urgent to employ aerostats to re-establish communications with the provisional government in Tours, which is required for numerous pressing reasons of a psychological as well as military and political nature.’19

Top-secret or not, rumours of this decision quickly reached the place Saint-Pierre. Nadar’s No. 1 Aérostiers were now desperate to be given the go-ahead, and fully rigged the Neptune for free flight. But still the Council delayed. Unknown to Nadar, another balloon was somehow procured by the Postal Services itself – possibly from the Godards – and clandestinely inflated at a hidden site in the Vaugirard gasworks, in the south-west of Paris, on the afternoon of 22 September. Its aeronaut was a professional, Gabriel Mangin. But the balloon was found to be in ‘a hopeless condition’, the pilot was unenthusiastic, and the launch was abandoned.20

At this point, on the evening of the 22nd, the Neptune was finally given secret instructions to prepare for a launch at dawn the following day. The task would be to carry an undefined amount of mail and government despatches to Tours. The westerly air current was favourable, but the Aérostiers had now been waiting in full readiness for over forty-eight hours. All this time, the old and worn-out balloon had been fully inflated but steadily leaking coal gas. Much battered after six years of Duruof’s festival flights, and the recent regime of tethered observation ascents, the Neptune had brittle varnish, numerous small punctures and splitting seams. It was now having to be repaired not merely daily, but hourly.

Throughout the night, the Aérostier team of volunteers steadily painted fresh cow-gum on the seams, and stuck on cotton patches as each new hole appeared. Nadar was hoping that the gentle westerly airstream would hold good. Duruof was quietly wondering how much the mail would weigh. Both of them privately speculated about whether the balloon would simply fall apart in the first hundred feet. The Neptune was, they said fondly, ‘a noble piece of wreckage’.

Finally, at 7 a.m., just after dawn on 23 September, the harassed Directeur des Postes, Monsieur Rampont-Lechin himself, arrived in a fiacre with several canvas sacks containing 125 kilos of despatches and public mail. This was the equivalent in weight of two extra passengers, for a balloon that had barely been able to lift a single observer. Watched by a grimly silent group of soldiers, Nadar and the Aérostiers team hastily loaded the mailbags, disconnected the municipal gas pipe, helped Jules Duruof into the basket, weighed off, and shook hands. Then they stood awaiting Duruof’s final command: Lachez-tout! – ‘Let go all!’

There is a photograph taken at this moment, just before the launch, from the grassy Butte just above the place Saint-Pierre.21 It shows the grey light of an urban dawn, a bleak huddle of Paris rooftops and windows, and the unpaved square almost deserted except for a group of dark figures in heavy coats clustered anxiously round the balloon basket. The balloon itself appears large, dirty and undecorated, swaying above the military bell tents, and casting no shadow. The long, thick snake of the gas pipe is still attached to the balloon’s mouth, so it was evidently being reinflated until the very last moment. To the left, a dispirited line of soldiers lounge as close as possible to Monsieur Charles’s café on the southern side of the Place. To the right, waiting behind Nadar’s cordon, are a sparse and dejected audience of some twenty people, most of whom appear to be small boys sitting on the ground. Contrary to later legends, there are no flags, no cheering crowds, no military band. It is a bleak and unglamorous image of grim determination.

illustration credit ill.143

Just after 8 a.m. – no balloon launch ever happens on time – Duruof shouted the irrevocable command, ‘Lachez-tout!’, and Nadar stepped smartly back from the heavily loaded basket. It was at once apparent that Duruof had a special flight plan in mind. Contrary to standard procedure, and using exactly the technique he had employed with Gaston Tissandier in Calais, he immediately cut away a huge sack of ballast and sent the ancient, creaking Neptune leaping vertically into the air. Whatever the risk of rupturing the old and rotten canopy, Duruof was absolutely determined to gain height and clear the Prussian lines. He might fall from the sky, but he would definitely not be shot out of it.

The Neptune rose with impressive speed, effortlessly cleared the nearest line of rooftops (the photograph shows nine-storey apartment buildings), and sailed away to the south-west. To Nadar’s amazement the scattered, apathetic group of soldiers suddenly began cheering, and the shouts and huzzahs were taken up by the small boys across the Place. Duruof’s fellow aeronaut Eugène Farcot recorded proudly: ‘Duruof took off in high style, shouting that he would see us all in Le Havre. He slashed away the trailing ropes, and emptied an entire sack of ballast, coolly setting out in the direction of Versailles, very much the old and practised routier of the air.’22

Wilfrid de Fonvielle, who also seems to have turned up for the launch, remarked admiringly: ‘Duruof challenged all the fury of the Prussian guns in an old, small, clapped-out balloon – he was a modern Curtius – he simply flung himself into the clouds, and went at them neck or nothing [à corps perdu]…He shot his balloon straight upwards like a shell from a mortar.’23

Duruof later left a detailed account of this first-ever balloon escape from the besieged city. Having reached a height of five thousand feet without disintegrating, the Neptune unexpectedly turned north-westwards, crossed the Seine, and floated slowly over the ‘black ant-heap’ of the Prussian lines beyond Mont-Valérien. Duruof could hear the sinister crackling of musketfire below, and hunched down low into his basket. He felt vibrations, but no direct hits. Only later was it established that 3,500 feet was the safe height, out of range of most standard Prussian weapons. But this had to be judged by eye, as few of the later siege balloons were equipped with anything as sophisticated and expensive as aneroid barometers.

On this occasion, by way of reply, Duruof threw out handfuls of printed business cards embossed ‘Nadar Photographe’. It was later said that each one had been marked personally by Nadar in the top right-hand corner: ‘Compliments to Kaiser Wilhelm and Monsieur Von Bismarck’.24

Duruof noted that the Prussians attempted to elevate their big field guns to fire up at him (like the Confederate artillery in the American Civil War), but without apparent effect. It was more disconcerting to see a line of Uhlan cavalry setting out in hot pursuit. But eking out what little remained of his ballast handful by handful, and throwing out more business cards, he nursed the leaking Neptune as it continued to drift north-westwards along the meandering line of the Seine.

To his immense relief, all signs of pursuit gradually disappeared after Mantes, apparently obstructed by the many twists of the river. Three hours after launching, at 11 a.m., he landed successfully at Corneville, near Evreux. He had travelled twenty miles, about a third of the way to Rouen. He was greeted ecstatically by the villagers, who could not believe that he had come from Paris until they were shown the official mailbags. Duruof commandeered a cart and trotted briskly to the nearest railway station, where by good luck he was able to board a direct train to Tours.

He arrived at Tours, with all the mail intact, by 4 p.m., and delivered his despatches to the government in exile. These included a special address to the nation from Léon Gambetta, which was printed in the next day’s newspapers throughout France. Gambetta announced that Paris was preparing ‘a heroic resistance’. All Prussian disinformation should be ignored. All political parties were united. The city could hold out all winter. ‘Let all France prepare herself for a heroic effort of will!’

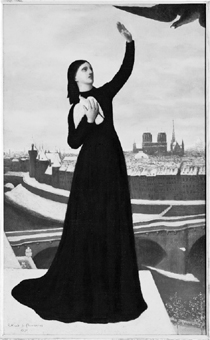

By the next evening the news had begun to spread like wildfire. It was not just the arrival of private mail, or Gambetta’s public message. It was the fact that the siege of Paris had been broken by a balloon. Prussian firepower had been beaten by French air power. Paris was airborne and alive. It was a technical, but above all, a huge propaganda, triumph. In celebration, the artist Puvis de Chavannes painted the figure of a defiant Marianne with fixed bayonet standing guard on the north-western ramparts, bidding farewell to a departing aeronaut. Completed in November 1870, the dramatic picture shows the balloon directly above Fort Mont-Valérien. It was made into a lithograph and widely distributed in Paris as a propaganda poster.

illustration credit ill.144

* This is the spectacular view the modern visitor still sees from the panoramic terrace of the Sacré Coeur. In those days neither the Basilica nor the terrace existed, and the Butte, or Heights, were only marked by the Solferino Tower, commemorating one of Napoleon III’s victories. There was also a popular restaurant, or guinguette, which charged extra for the panoramic view. Both were demolished in the winter of 1871, when it became clear that Prussian gunners were using them as sighting points for their bombardment. The Sacré Coeur, commenced in 1873, was originally intended to commemorate the Franco-Prussian conflict and ‘to expiate the crimes of the Commune’. Its completion was endlessly and symbolically delayed until 1919. Today its stark white cupolas, uneasily tethered on the skyline of Montmartre, still seem to retain some memory of its earliest aeronautical associations. On the place Saint-Pierre below, there is usually a children’s carousel which marks almost exactly the spot of Nadar’s balloon launches. The garden at the side has been renamed the square Louise Michel, in honour of the famous female communard. But Nadar and his heroic Aérostiers have no monument or memorial. Perhaps he would prefer the children’s carousel anyway, as it inspires so many happy photographs.

The propaganda moved beyond France. Among the mails Duruof carried was an open letter from Nadar to The Times in London, appealing for international support. It was copied by government clerks at Tours, and then immediately sent on by train to Le Havre, where it was transferred to a steamship, offloaded at Dover, and delivered by overnight Royal Mail express train to the Continental sorting office in London. Finally it was published by The Times in the first edition of 28 September 1870, a mere five days after it had left Nadar’s bell tent on the place Saint-Pierre. It appeared on the editorial page under the dramatic title ‘From a Balloon’.

The Times also chose to make this day a special siege edition. It took the almost unheard-of step of publishing on its sacrosanct front page a huge, half-page map of ‘Paris and Environs’. Actually what it showed was ‘Paris and its Defences’. It displayed all the central arrondissements, the inner ring of defences, the disputed outlying villages, the main redoubts and ramparts, the twelve perimeter forts, and all the incoming roads and railway lines (though of course these were now cut). The level of detail is extraordinary, and copies must soon have been pinned up in every Prussian officer’s tent and mess room. Given The Times’s anti-French bias, this is quite possibly what was intended.

Nadar understood the business of publicity and propaganda as well as, perhaps better than, any politician in Paris. He was also aware of the probably hostile attitude of Times readers. So his historic balloon letter consisted of just three short paragraphs, which the newspaper left entirely in their original French. He omitted any of the expected Gallic melodrama, self-justifying rhetoric or flamboyant heroics. The tone was modest, down-to-earth, frank.

Nadar began by thanking The Times for the ‘hospitality’ of its pages. (He was of course providing it with a sensational balloon scoop.) On previous occasions the newspaper had been ‘extremely severe’ towards ‘imperial France’, and it had been largely justified in this attitude. He himself – ‘moi Français’ – was indignant and ashamed at ‘the deplorable example my poor, benighted country’ had given over the last twenty years. It was undoubtedly imperial France’s ‘error’ to declare ‘this abominable war’ against the Prussians.

But now he begged English readers, with their famous sense of fair play, to reconsider the position. Here was a new, young, idealistic French republican government in power. Its peace proposals had been ‘disdainfully’ refused by the Prussians. Its sovereign lands had been ‘cruelly’ invaded and despoiled, by an enemy which had become ‘greedy and overconfident’. Most of all, the Prussian military hostilities were now being pursued not merely against the French army, but against the civilian population itself, the ordinary ‘people of France’.

The whole temper of that people, the people of France and specifically the people of Paris, was profoundly altered. ‘I could only wish, Sir, that you could bear witness to the sudden, unexpected sight of Paris transformed and regenerated, and now standing utterly alone in the face of supreme danger. The city of pleasure and frivolity has become silent, grave, and serious-minded.’

‘Wars,’ Nadar concluded pointedly, ‘are not won with cannons and rifles alone – there is also the small matter of having right on your side.’ Prussia had become an ‘insatiable’ enemy, too sure of itself, too self-justifying, too vindictive. Imperial France had been justly punished in the first place. But now it was Prussia’s turn to receive just punishment, a punishment that it had brought upon itself: ‘La Prussie va recevoir le châtiment qu’elle provoque.’ For readers of The Times, many of whom would have known Victor Hugo’s poetry, Nadar’s clinching sentence must have had a particular ring.25 A version of this same letter also appeared in L’Indépendance Belge on the following day, 29 September. The communications blackout had been decisively broken.

Three more balloons followed in quick succession over the next week, on 25, 29 and 30 September. Their aeronauts were Gabriel Mangin (his second attempt), Louis Godard and Gaston Tissandier, and they took off from the gasworks at La Villette and Vaugirard. All three of these balloons crossed the Seine and landed safely to the west of Paris carrying mail. They also carried baskets of carrier pigeons provided by a patriotic ‘columbine’ society, L’Espérance, to see if replies to the despatches could be flown back into Paris from the sorting office in Tours. When several of the pigeons returned over the next few days, it was clear that a complete outward-and-return postal service was now possible.

The Defence Council now officially announced the formation of the Paris Balloon Post.26 There were to be two kinds of delivery: monté and non-monté – by manned and by unmanned balloons. The first would take proper private letters; the second would accept only official ten-centime postcards with standardised message boxes to tick. Naturally, only the first ever caught on with the Parisians.

illustration credit ill.145

The third of the balloons, Le Céleste, was manned by Gaston Tissandier, who landed near Dreux, seventy miles due west of Paris in the department of Eure-et-Loir. He broke his arm, but still delivered the mail. Tissandier was also tasked with setting up a communications centre at Tours, and investigating all the possible methods of getting messages back into Paris. His ingenious professorial brain came up with numerous ideas, including not only carrier pigeons, but also messenger dogs, river flotation bags, and even balloons flown back into the city. His concept was that, as in the American Civil War, balloons could be mounted on trains. They could then be rapidly deployed to positions precisely upwind from Paris on any particular day, inflated and immediately released.

It was a supremely hazardous undertaking, but morale was high. Tissandier wrote: ‘The appearance of these first balloons in the provinces produced universal excitement and enthusiasm. In less than eight days, literally tens of thousands of families had received precious news from their besieged relatives by means of the air.’27

illustration credit ill.146

He was not exaggerating. As the weight of each letter was limited to four grams, Duruof’s original 125-kilo mailbag had held over three thousand letters. The next three balloons carried two or more mailbags each, totalling between them over nine hundred kilos of mail. This produced a grand total of well over twenty-five thousand letters delivered by the first four siege balloons in the last week of September 1870. These numbers would soon rise dramatically.

Victor Hugo wrote to Nadar: ‘One would have to be a pinhead not to recognise the huge significance of what has been achieved. Paris is surrounded, blockaded, blotted out from the rest of the world! – and yet by means of a simple balloon, a mere bubble of air, Paris is back in communication with the rest of the world!’28

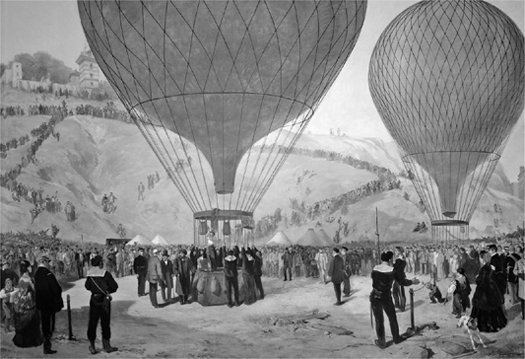

The new Defence Council decided on a propaganda coup. On 7 October the fifth and sixth balloons, christened the Armand Barbès and George Sand, were launched simultaneously from Nadar’s place Saint-Pierre. The dual launch was partly intended to confuse the Prussians, for aboard the Armand Barbès was the key member of the new republican government, Léon Gambetta. A radical lawyer and journalist, already known and admired as the dynamic Minister for the Interior, Gambetta had become the hope of all France. Still in his thirties, he was renowned for his populist sympathies and fiery, patriotic speeches.

The council had appointed him Minister for War, and given him the crucial task of energising and reorganising the provisional government in Tours. His instructions were to mobilise the population, recruit fresh troops, and put the army of the Loire on a renewed and aggressive footing. In short, he was to inspire ‘the sentiment of resistance’ throughout the south and west of France. With Gambetta went the editor of the leading newspaper La République Française, whose parallel job was to revitalise political publicity for the provisional government.

Altogether, it was a brilliant but risky initiative. The Journal des débats called it the launching of the ‘Balloon Government’. But some critics believed it was, rather literally, putting all their eggs in ‘one basket’. In the event of their deaths, or – even worse – their capture alive, the propaganda coup would turn devastatingly in favour of the Prussians.29

Victor Hugo later recorded in his vivid diary, Choses vues, how he happened to be out ‘wandering the boulevards’ that morning, and turning his steps towards Montmartre, chanced to witness the last few minutes before the launch. In fact he had almost certainly been alerted by the ever-resourceful Nadar. Hugo found quite a crowd in the big, bleak square: a detachment of General Trochu’s infantry, a cluster of bemedalled officers, a whispering group of Parisian workers, the assembled Aérostiers, and Nadar looking pale and exhausted. Then there were the two balloons, one dirty yellow – the Armand Barbès – and one dirty white – the George Sand – neither in the least impressive.

illustration credit ill.147

The white balloon was festooned with limp tricolour flags, and was clearly intended as the decoy. Nonetheless the George Sand carried a full payload of mail, and also two dauntless American businessmen, a Mr Reynolds and a Mr May, who were going to arrange a huge arms deal for Gambetta. Besides, Hugo noted, this was a literary balloon and a lady’s balloon as well: the novelist’s name alone would certainly put the philistine Prussians in their place.30

Hugo’s diary recorded tersely:

There were whispers running through the crowd: ‘Gambetta’s going to leave! Gambetta’s going to leave!’ And there, in a thick overcoat, under an otter-fur cap, near the yellow balloon in a huddle of men, I caught sight of Gambetta. He was sitting on the pavement and pulling on fur-lined boots. He had a leather bag slung across his shoulders. He took it off, clambered into the balloon basket, and a young man, the aeronaut, tied the bag into the rigging above Gambetta’s head. It was 10.30, a fine day, a slight southerly wind, a gentle autumn sun. Suddenly the yellow balloon took off carrying three men, one of them Gambetta. Then the white balloon, also carrying three men, one of them waving a large tricolour flag. Under Gambetta’s balloon was a small tricolour pennant. There were cries of ‘Vive la République.’31

illustration credit ill.148

This historic moment was also commemorated in several popular prints and engravings, some more imaginative than others. The main difference between them lies not in the depiction of the balloons, but in the attitude and mood of the watching soldiers and Parisian crowd. In some, the mood is evidently tense and sober, even sceptical. In others the crowd is packed, wildly supportive and enthusiastic.

One possibly genuine photograph has survived, which shows the moment after lift-off in the place Saint-Pierre. The Armand Barbès is about twenty feet up, swinging in what is evidently a high wind (not Hugo’s gentle breeze). There are no tricolour pennants attached anywhere. Gambetta, looking tense, has grabbed the edge of the basket to steady himself, and is dramatically holding out his fur hat to bid farewell to a small group of soldiers and civilians below.

But the mood is subdued. On the left, some soldiers raise their képis, one gentleman doffs his top hat, a guardsman stands impassively leaning on his musket with fixed bayonet. To the right, near the solitary gas lamp, the tall, spindly figure of Nadar can be seen standing alone, still and solemn, his right arm raised in a silent salute. Behind him, near the bell tents, are a loose circle of about a dozen watching militia men, either standing or sitting. Not one has either lifted his hat or raised his arm. Compared to the popular prints, the square is shown as largely empty, and the ground scattered with hastily discarded ballast sacks. Even if some of the figures have been improved, the authenticity of the bleak photograph is striking.

illustration credit ill.149

Owing to an unexpected wind shift, Gambetta’s balloon suddenly turned almost due north, passing over Saint-Denis and Le Bourget, an area known to be infested with Prussians. Nadar watched it with binoculars from the Butte, ice in his heart. Worse, the Armand Barbès could not gain sufficient height before crossing the siege lines. A brisk fusillade of musketfire rose up towards them, some balls hissing past, and several striking the base of the willow basket with a sharp crack. Then some actually pierced the canopy, causing the support ropes to vibrate above the passengers. It was a moment of terror. But as the American Civil War aeronauts had discovered, these produced only tiny, neat punctures and failed to ignite the gas.

But the position was still perilous. Gambetta was grazed in the hand by a musketball, and fell back stunned against the sacks of mail. The balloon lost buoyancy, sank, and actually came down in a field near Chantilly that had just been vacated by a squadron of Uhlan cavalry. Alerted by warning shouts from field workers, the pilot hurled out ballast and the Armand Barbès lurched back into the air again. The Prussian cavalry, in full cry, pursued them cross-country for several miles, as in some nightmare dream sequence. When they crossed the village of Creil, twenty-seven miles from Paris, they were still only seven hundred feet above the ground, well within musketshot.

illustration credit ill.150

Finally, after about three hours, they skimmed over the heavily wooded region of Compiègne, near Epineuse, thirty-eight miles from Paris. Here they seemed to have temporarily lost their pursuers, and the pilot decided to risk a quick emergency landing. But he missed the open ground, and crashed into an oak tree, where the balloon hung suspended in the branches for several minutes, helpless should the Uhlans arrive. Eventually some local villagers climbed up and pulled them clear, bundling them and the mailbags unceremoniously into a hay cart. It is not clear whether Gambetta was recognised at this point, or even if the villagers realised that they were dealing with Parisians rather than Prussians. It was also said in some reports that the bearded man had been found hanging upside down from the anchor rope.32

Luckily, the mayor of Epineuse did recognise Gambetta, and realising the imminent danger from Prussian troops, transferred the whole party into his private coach and hurried them northwards towards Amiens. Halfway there, at the village of Montdidier, Gambetta was bandaged and revived with stiff tots of eau de vie. He sent off a suitably clipped and optimistic message by carrier pigeon:

Arrived after accident in forest at Epineuse. Balloon deflated. Escaped Prussian rifle fire thanks to mayor of Epineuse and reached here Montdidier whence leave one hour for Amiens then railway to Le Mans or Tours. Prussian lines end at Clermont, Compiègne, Breteuil in the Oise. No Prussians in the Somme. Everywhere the people are rising. Government of National Defence acclaimed on all sides. – Léon Gambetta.33

At Amiens, they spent the night recovering, and by the following evening they – and the mailbags – had safely reached Tours via Rouen. The crew of the George Sand were already there. At the railway station, lined with National Guards, Gambetta climbed up on a porter’s trolley and gave one of the great fighting, patriotic speeches with which he would rouse the nation: ‘If we cannot make a pact with Victory, let us make a pact with Death!’ The republican government in exile proclaimed a mighty propaganda coup.34

From then on, the National Council for Defence was committed to balloons. It was clear that they were fully capable of breaking the Prussian siege, and that combined with the railway network, they could outwit and outrun the Prussian occupation forces beyond Paris. Two non-stop balloon-manufacturing centres were quickly established: one at the Gare d’Orléans (now Austerlitz), under the Godards; and the other at the Gare du Nord, under one of Nadar’s original Aérostiers, Camille Dartois.

The high-ceilinged stations were empty of trains and so provided huge and convenient open-plan buildings where balloons could be mass-produced. The vast stretches of balloon material were spread out on huge trestle tables, where they were cut, sewn and varnished by hundreds of volunteer dressmakers. They could then be hung from the overhead iron girders above the tracks, inflated with air pumps, dried, and moved rapidly to their launch sites at the La Villette and Vaugirard gasworks.

The plan was to mass-produce a standard siege balloon of seventy thousand cubic feet, made of cheap calico, capable of taking two men, a cage of pigeons, and at least three hundred kilos of mail. They were essentially ‘disposable’, designed to last for a single flight. The Dartois balloons from the Gare du Nord were plain, no-nonsense white – like button mushrooms in the sky, it was said; while Godard’s balloons at the Gare d’Orléans were all candy-striped, suggesting a certain teasing spirit of levity in the face of Prussian boorishness.35

illustration credit ill.151

Crucial to their propaganda value were the names assigned to each balloon. Knowing that a thousand Prussian telescopes and field-glasses would be furiously trained on every canopy as it floated slowly overhead, the Defence Council launched above the Prussians a veritable checklist of French genius. But admirably, and in the true Enlightenment tradition, they did not limit themselves exclusively to French citizens. In effect they sent over an airborne cours de civilisation.

The balloon names naturally included many inspiring soldiers and statesmen: Lafayette, Armand Barbès, Gambetta, Louis Blanc, Washington, Garibaldi and Franklin. But equally there were many scientists: Archimède, Kepler, Newton, Volta, Davy, Lavoisier. There were some inventors: Daguerre, Niepce, Montgolfier; but surprisingly only two writers: Victor Hugo and George Sand. There were a number of patriotic salutes: La Ville de Paris, La Ville d’Orléans, La Bretagne, La Gironde, L’Armée de la Loire. Finally there were several well-chosen political watchwords for the Prussian soldiery to consider: La Liberté, L’Egalité, La République-Universelle, La Délivrance. There was also the occasional direct provocation: on 17 December they sent up a balloon named Le Gutenberg.36

Of course all these names also heartened the French patriots below, not least in Paris itself, and served to stiffen the ‘sentiment of resistance’. It is true that later, when night launches were adopted, this propaganda became much less visible, at least to the Prussians. Yet these balloon names continued to be circulated in military reports, newspaper editorials and news telegrams on both sides; and eventually had their rippling propaganda effect right across Europe and as far afield as Scandinavia and America.

Hugo was delighted when Nadar arranged for balloon No. 13 to carry his name skyward. The Victor Hugo was launched on 18 October, and piloted by a member of the No. 1 Aérostiers, Jean-Pierre Nadal. In an exceptional gesture, the launch site was fixed in the gardens of the Tuileries, to achieve maximum publicity. The balloon rose amidst cheering crowds, carrying besides its cargo of postbags and pigeons several thousand copies of a hastily-written propaganda letter by Hugo addressed ‘To the Prussians’. It urged them, in the most magniloquent terms, to sign an honourable armistice, leave French soil and march peacefully home. ‘I believe its effect,’ confided Hugo, ‘will be incalculable!’37

From 7 October 1870, depending on wind direction and weather conditions – and it was becoming a bitter winter – postal balloons were launched regularly two or three times a week. Night launches began on 18 November. A total of over fifty balloons had been launched by the end of December. The Prussians were not amused by all this, and Bismarck was recorded as remarking drily, ‘Décidément, ces diables de Parisiens sont bien ingénieux.’ He was pleased when three balloons, the Normandie, the Galilée and the Daguerre, were unexpectedly captured in November, having landed behind enemy lines in bad weather. Both the crews and the mailbags sinisterly disappeared.

Bismarck wrote to the American Ambassador shortly after: ‘I take this opportunity of informing you that several balloons sent out of Paris have fallen into our hands and that the persons travelling in them will be tried by a court martial. I beg you to bring this fact to the French government’s notice, adding that any person using this means of transport to cross our lines without permission, or to engage in correspondence to the detriment of our troops, will be subjected, if they fall into our power, to the same treatment.’38 This was a fairly explicit warning that balloonists would not be treated as regular combatants, but would be summarily shot as spies.

After the capture of the three balloons, launches from La Villette and Vaugirard tended to be at night, allowing them several hours of darkness to clear the Prussian lines. But this made navigation even more haphazard. Uncertain of their line of flight or their location, fearful of being shot as spies if they were captured, aeronauts were inclined to press on as far as possible before they came down low enough to establish their whereabouts. This resulted in some fantastic long-distance flights, but also several tragic disasters.

La Ville d’Orléans took off on the night of 24 November, ran into a storm, and landed fifteen hours later on a snow-covered mountainside in Norway. It was a record distance of 840 miles, at an average speed of just under sixty miles per hour, passing through air temperatures as low as −32 degrees Fahrenheit. Astonishingly, the two-man crew managed to hike through snowdrifts to Christiana (present-day Oslo), and all the mailbags but one were safely retrieved by Norwegian farmers.39

Le Jacquard, launched on 28 November, disappeared in another direction, over the Irish Sea, and was never seen again. Its one-man crew, a twenty-seven-year-old sailor named Alexandre Prince, had given a number of rousing patriotic interviews before his departure, and became the subject of several poems and posters after his mysterious disappearance.* La Ville de Paris, launched on 15 December, landed in Wetzlar, Germany, where its mail was immediately seized and its crew probably shot. Le Général Chantzy, launched on 20 December, went as far east as Bavaria, and met a similarly unknown fate.

Despite these tragic failures, the Parisian enthusiasm for balloon post did not falter, nor the supply of aeronauts to deliver it. In fact balloons swiftly became vital to Parisian morale, a heroic part of the siege mythology. ‘The wind was our postman, the balloon was our letterbox,’ recalled the poet Théophile Gautier. ‘With each departing aeronaut, our deepest thoughts also took flight, our hopes and fears, our wishes for absent loved ones, our heartaches and our longings, everything that was good and fine in the human spirit … took to the air.’41

* The mystery of Le Jacquard throws some light on the spirit of the siege balloonists. Prince had never been in a balloon before, but in the last-minute absence of a regular aeronaut, he volunteered to fly from the Gare d’Orléans on a night launch. ‘I reckon to make a good long flight,’ he said simply. ‘People will talk about my trip.’ His instructions were basic. He was not to come down anywhere before dawn. He must be absolutely certain that he was completely clear of the Prussian lines. The mail must only be delivered into friendly hands. He was last reported by a British fishing boat, thirty miles due west of the Scilly Isles, and flying exceptionally high. However, some of his mailbags were later found among the rocks at the Lizard, the most south-westerly point of England. What had happened? His flight path on a marine chart indicates a roughly straight trajectory between Paris, Cherbourg, the Lizard and the Scilly Isles. While still flying low, Prince probably saw the tip of the Lizard below, and realised it was his last possible point of landfall before the Atlantic Ocean. So he deliberately threw out his mailbags in the desperate hope that they would be found and delivered, even by the English. (In fact some of this mail actually was later delivered.) But in doing so he was throwing out a large part of his remaining ballast. As he must have known, Le Jacquard was doomed to gain massive height and to continue ever westwards over the Atlantic Ocean. Alexandre Prince’s story – the lone figure in the high balloon headed west into the sunset – had a peculiar power to haunt Parisians. His name can be found in golden letters on a solitary memorial in the Salle des Pas Perdus, in the present Gare d’Austerlitz.40

With thousands of private letters going out each week from Paris, the increasingly urgent question was how to organise a postal reply system. Albert Tissandier – not to be outdone by his younger brother – had successfully flown out in the Jean-Bart on 14 October. He now joined Gaston in his attempts to establish a balloon service, flying back into Paris with sacks of return mail. After taking meteorological advice about the prevailing autumnal winds, the brothers set up Rouen, on the river Seine, as their centre of operations. They were sixty-eight miles north-west of Paris, potentially a four-hour flight back to the capital. With the approval of Tours, a temporary mail-sorting bureau was established at the Rouen post office, with letters from all over France being brought in by rail. On 7 November they took off in the Jean-Bart from Rouen gasworks, carrying 250 kilos of return mail on a promising south-easterly air current.

Their plan was to follow the meandering line of the Seine all the way to Paris. By evening they had gone twenty miles in precisely the right direction, and when the wind dropped at dusk, they came down stealthily outside the little town of Les Andelys on the Seine. They were now only forty-nine miles from Paris, and had every hope of reaching their destination the next day, although they were dangerously close to the Prussian lines. But the next morning the wind had backed and was blowing to the north. The Tissandiers bravely relaunched, hoping to find a southerly wind at a higher altitude. They spent the entire day in freezing clouds at ten thousand feet, unable to see anything beneath them, and experiencing temperatures of 14 degrees below zero, but calculating that if they could only hold on, they should be over Paris by dusk.

When they finally came down, they found themselves suspended above the middle of the Seine and surrounded by steep cliffs and dark, impenetrable woods. They were in the forest of La Bretonne, at Heurteauville, far to the north of Rouen. To their dismay, they realised that they had gone backwards, and were now eighty-one miles from Paris. They were only saved from drowning when some villagers rowed out under the light of the moon and succeeded in towing the Jean-Bart to the shore. The whole attempt was then abandoned. Afterwards, Albert Tissandier insisted that it was not an entire failure, as it gave him the subject for a wonderful engraving of the moonlit rescue.42

Gaston now considered other fantastic schemes to get mail back into Paris. Some were proposed by the Académie des Sciences, some by fellow aeronauts, some by more eccentric members of the public. Among the most imaginative suggestions sent in were a plan to harness the eagles from the Jardin des Plantes; a blueprint for a small steam-powered dirigible balloon; the concept of floating the mail down the Seine in camouflaged containers; and the almost surreal proposal to suspend a seventy-mile aerial telegraph line, on a chain of free-flight balloons, all the way up the length of the Seine from Rouen to the capital.43

But pigeon post remained the tried and obvious method. Baskets of homing pigeons had gone up with every balloon after the Neptune. The problem was that their return flights were unreliable, and besides, each pigeon could only carry half a dozen brief messages, laboriously copied in tiny handwriting, and slipped into a leg ring. What was required was some ingenious way of hugely increasing each pigeon’s postal payload. Each bird needed to carry not a dozen messages, but several hundred. Hence the fanciful idea of employing eagles.

The crucial technical discovery depended not upon eagles, but upon photography. Once again, the idea seems to have been conceived by Nadar, although it was actually pioneered by another commercial Paris photographer, René Dagron.44 The key idea was the use of microfilm. Throughout October, working quietly in his Paris laboratory at the rue Neuve des Petits-Champs, Dagron invented a simple but revolutionary system of photographing letters and then reducing them to miniaturised film negatives. His method was this. He mounted hundreds of letters at a time onto huge flat boards, and then photographed them with a single exposure taken from a fixed camera. These letter-boards could be photographed as fast as they could be mounted, the letters simply being placed side by side under a retaining sheet of glass. Each photograph was then reduced to a single tiny negative, on part of a roll of collodion film. The process was very rapid, very economical, and easily repeatable. The result was a single roll of collodion microfilm, no thicker than a roll of cigarette paper, which could easily be inserted into a goose quill. The quill could then be attached to a carrier pigeon’s tail feathers with waxed silk thread.45

Astonishingly, each collodion roll contained enough negatives to record well over a thousand two-page letters. As each goose quill could take four or five collodion films, one rolled tightly inside the other, a single pigeon could carry up to five thousand letters. Moreover, each roll could be reproduced scores of times, so that many copies could be sent by many different pigeons. Thus the chance of at least one safe home-run was greatly increased.46

It was Nadar who first heard about Dagron’s work, and introduced him to his old contact Monsieur Rampont-Lechin, head of the Bureau de Poste. Nadar wrote Rampont a beautifully clear, technical letter describing the whole process, as precise and detailed as a patent claim, and recommending Dagron to lead the project. He was undoubtedly shocked when Dagron negotiated a large fee with the government, and, when asked to fly out to Tours, added twenty-five thousand francs of danger money. This was hardly in the spirit of the Aérostiers.47

On 12 November, four days after the failure of the Jean-Bart expedition, Dagron flew out of Paris aboard Le Niepce, carrying a precious cargo of cameras and microfilm equipment, weighing six hundred kilos. His secret mission was to explain and install this top-secret message system at Tours, and then at Clermont-Ferrand, well clear of the Prussians. The balloon had a difficult flight, descending over the Marne, and Dagron and his weighty photographic kit barely escaped capture after a rough landing and cross-country pursuit. But by the end of November the first microfilm pigeon posts were flying in.

Meanwhile, the Bureau de Poste in Paris had organised a mass-distribution system. Whenever a pigeon returned to a rooftop roost anywhere in the city, it was inspected by a duty pigeon officer. Certain pigeon roosts or colombiers became famous for their successes, but all roosts were manned twenty-four hours a day. The precious rolls of collodion film were immediately extracted from the pigeon’s quill, and rushed over to the Bureau within minutes of their arrival. Here the films were carefully unwound and cleaned, by soaking them in a mild ammonia solution. They were then cut up into separate strips of negatives, and slipped into a battery of magic lanterns. These projected the negatives onto large screens, permanently installed in a series of darkened transcription rooms. Once magnified through the lanterns’ special lenses, the individual letters and despatches became as large as posters, and were easily legible.

A team of clerks, also on continuous twenty-four-hour duty, sat in front of the large, luminous screens, transcribing the letters and despatches back onto paper. This, of course, was the slowest, most exhausting and least reliable stage of the process. The hot, dark, smoke-filled transcription rooms were places of tension and high drama. The clerks saw fragments of history in the making, but were also privy to intimate family business, passionate lovers’ letters, and the endless heartbreaking private tragedies of war. There seems to have been little censorship. Government despatches got priority, but all post was eventually sorted and delivered to its destination throughout Paris, usually within a week. By this technique a single pigeon could carry enough written material to fill the pages of an average-size novel. (Indeed, it is odd that these exceptional circumstances did not actually produce a novel.)

illustration credit ill.152

The Prussians naturally took counter-measures, including regular shooting patrols using buckshot cartridges, and, most effectively, teams of hunting hawks and trained falcons. But probably the winter weather took the greatest toll. Between September 1870 and February 1871 around 360 carrier pigeons were released, but only fifty-seven made it home to Paris, a success rate of about one in six. But because of the system of microfilm and pigeon duplication, the actual success rate for message delivery was far higher. Some ninety-five thousand individual letters and despatches were sent from Tour and Clermont-Ferrand. Of these it is estimated that more than sixty thousand items were finally delivered to their addressees in the besieged city, a success rate of more than one in two.48

The arrival of pigeons became as significant to Parisians as the departure of balloons. Both became part of the psychology of the city’s resistance, and eventually its mythology. Just as the named balloon launches were announced beforehand, so the news of the latest pigeon-post arrivals would be officially advertised in the press. The pigeons too were given names: Gladiator, Vermouth, Fille d’air. Households all over Paris would wait in anticipation for their arrival. International news was vital to morale, and was quickly printed in the wartime editions of Le Moniteur, Le Journal des débats and other Paris papers. But family news – health, money, food, children, domestic animals, gardens – was at a premium. And there was always the shadow of the Prussians. ‘In all history, there will never have been a more beautiful or more touching legend than that of these saviour birds,’ wrote the journalist Paul de Saint-Victor. ‘They brought back to Paris the promise of distant France, the love and memories of so many separated families.’49 Once again Puvis de Chavannes produced a poignant picture, The Pigeon, showing the now emaciated figure of Marianne on the Paris ramparts. This time she is shielding a carrier pigeon, and warding off a Prussian hawk, with the belfries of Notre Dame symbolically in the background.

Letters between wartime lovers were particularly important and intense. Even the ageing Théophile Gautier tried to keep in touch with his mistress, the beautiful dancer Carlotta Grisi, who was safely ensconced in her manor house in Geneva. Like so many others, he despatched a fortnightly stream of duplicated letters, faithfully sent by each departing balloon post. He numbered each of the letters (over seventeen are known) so that lost ones could be identified. He also dated them, like many correspondents, according to the number of siege days that had elapsed.

illustration credit ill.153

On 30 November 1870 Gautier wrote duplicated letter No. 7, ‘on 74th day of Siege’:

Darling Carlotta … This morning I regaled myself with a rat pâté which wasn’t at all bad. You will understand the sadness of our life. The rest of the world no longer exists for us … Ah! My poor Carlotta, what a wretched year, this 1870. What events, what catastrophes! And all without the solace and sweetness of your friendship … I imagine that my dear ones might be ill, unhappy, or what would be far worse, forgetful. A balloon is leaving tonight: will it be more fortunate than the earlier ones that were captured?…Be assured that if I do not come and see you, it is merely the fault of 300,000 Prussian soldiers.50

Victor Hugo put both the balloons and the pigeons into many of the forty-five poems collected in his remarkable month-by-month verse journal of the Paris siege and the Commune, L’Année terrible. They became explicit, airborne symbols of Parisian resistance to the Prussians. Again and again Hugo uses the lyrical image of the dawn light in the east, with the silhouette of a departing balloon or the tiny flicker of an incoming pigeon: ‘the ineffable dawn where fly the doves’.51

Perhaps the most unusual of these resistance poems is his ‘Lettre à une Femme’ – ‘Letter to an Unknown Woman’. It is dramatically subtitled ‘Par Ballon Monté, 10 Janvier’.52 January 1871 was the final month of the siege, and this is central to the bravado of Hugo’s poem ‘sent by manned balloon’ (probably the Gambetta, which left at 3 a.m. on 10 January). By this time General von Moltke had finally overcome Bismarck’s scruples, and the Prussians had begun to bombard the centre of Paris five days before, on 5 January. This was the first time in modern history that a great European capital, and its overwhelmingly civilian population, had been bombarded. It caused profound shock. Over twelve thousand shells fell without discrimination, mostly on the Left Bank, striking the Panthéon, the Salpêtrière hospital, the Montparnasse cemetery and the Sorbonne.53

Ignoring these horrors, Hugo summons up, with a surprisingly light touch, the more banal daily discomforts of the siege. He refers to the sight of the raw tree stumps all along the Champs-Elysées, the icy chill of the unheated apartments, the huge queues outside the food shops, the constant thump of incoming Prussian shells, the drunken, desperate soldiers singing in the streets at night, and the awful massacre of the animals (‘We consume horse, rat, bear, donkey … our stomachs are like Noah’s ark’). There are also the small, insidious, personal privations: no clean shirts, no gaslight to work by, no white bread, the reduced diet of vegetables (‘Onions are worshipped like gods in ancient Egypt’). Above all, there is the awful gloom of the early-night-time blackout in the erstwhile City of Light: ‘at six in the evening descends the dark’.

illustration credit ill.154

But the message of Hugo’s resistance poem is that the old pleasure-loving Paris has been transformed, just as Nadar had claimed in that very first balloon letter to The Times. Paris has learned to accept all these hardships, without complaints, in the name of France. She will never surrender. Paris can take it. This image of Paris as a beautiful, stoic, unconquerable woman is the one that Hugo most wants to project. But she is also male in her determination – ‘un héros…une femme’. While Moltke bombards the Parisians, and Bismarck starves them, this strange, smiling, symbolic figure stands defiant on the ramparts. She – or he – gazes upwards, ‘at the balloon that sails away, at the pigeon that flutters back’.

Soit. Moltke nous cannone et Bismarcke nous affame.

Paris est un héros, Paris est une femme!

Il sait être vaillant et charmant; ses yeux vont

Souriants et pensifs, dans le grand ciel profond,

Du pigeon qui revient au ballon qui s’envole!

In fact Paris was bombarded into submission within three weeks. The city capitulated on 28 January 1871, in the nineteenth week of the siege. The Prussians marched briefly down a deserted Champs-Elysées on 1 March, exacted enormous punitive reparations, and the Commune of Paris erupted in April. The penultimate siege balloon, Le Richard Wallace, named after the British philanthropist who paid for the municipal fountains of Paris, had left from the Gare du Nord at 3.30 a.m. on 27 January. Manned by the last of Nadar’s original Aérostiers, Emile Lacaze, it flew fast and sure, almost due west, covering over 350 miles and reaching the large naval port of La Rochelle on the Atlantic coast in the late afternoon.

Sailors spotted Lacaze, flying low, and shouted for him to valve gas and come down. Witnesses later said that he waved to people on the quayside, and then unaccountably threw out sacks of ballast, gained height and sailed on over the bay of Arcachon, and out into the open Atlantic. He also threw out his mailbags, since several of them were later washed up on the shore.56 No one knows exactly what Emile Lacaze had in mind. Perhaps his release valve had jammed, like Major Money’s long ago. Perhaps, like Alexandre Prince, he deliberately sacrificed his own life for the mail. Or perhaps he simply could not bear the thought of Paris surrendering. Perhaps the last of the Aérostiers was determined to head on out to America, the land of the free, three thousand miles away. At all events, neither Lacaze nor Le Richard Wallace was ever seen again.

* Hugo’s other heroic siege poems include ‘Paris bloqué’, ‘Du Haut de la muraille de Paris’, ‘Les Forts’ and ‘Le Pigeon’. But his letters and prose diary suggest that the siege sometimes rather suited him. As well as being cosseted by his ageing but ever-faithful mistress Juliet Druot, and provisioned by generous well-wishers, his diary shows that he was also privately visited by a stream of late-night female fans and acolytes. Most brought small, innocent offerings, billets-doux, sweetmeats or poems. But some were anxious to offer various forms of sexual favour to the great man. Among these were Gautier’s unhappily married literary daughter Judith Catulle-Mendès, and none other than the future Communard leader, the fiery and headstrong Louise Michel.55