From this time on, the dream of free flight was increasingly handed over to proponents of various forms of heavier-than-air machine. As Nadar and Tissandier had seen in France, Sir George Cayley in England, Count von Zeppelin in Germany and Samuel Cody in America, the future lay with the engine-powered airship; and very soon with the true fixed-wing aeroplane. The romantic age of the free gas balloon was passing. As Victor Hugo had predicted, the future lay with the bird, not the cloud.

Or, more strictly, the future lay with the bird’s aerofoil rather than the balloon’s envelope. Despite generations of would-be birdmen, it was not the flapping of birds’ wings that ultimately held the clue to human flight, but the basic shape of their wing feathers. Birds’ wings form a natural aerofoil. They are not flat or paddle-like, as one might think, but curved and concave. Amazingly, this basic aerofoil shape can be observed even in an individual wing feather.1 This makes the upper surface area of each wing larger (or longer) than the lower one. In consequence, the air has to flow more rapidly over the upper surface, and more slowly over the lower surface. This produces a thinning or decrease of air pressure above the wing, and a corresponding build-up or increase of pressure beneath the wing. So, as a bird’s wing moves through the air, it is in effect pushed upwards from below, and simultaneously sucked upwards from above. These combined forces produce aerodynamic lift, or flight. Moreover, this sort of flight, unlike balloon flight, is independent of wind direction. By adjusting the aerofoil curve of each wing separately, a bird can turn, climb and dive freely in three dimensions. Not even an airship could really achieve this.

Working airships would appear in France by the end of the 1880s. Charles Renard made seven flights out of Paris and back in an electric-powered airship in 1884–85.2 In Germany, an experimental Zeppelin – with an aluminium body and a Daimler petrol engine – would fly over Lake Constance in 1900. The Wright brothers flew their aeroplane at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in December 1903; and Louis Blériot crossed the Channel in July 1909.

Meanwhile, aerostation itself began to seem old-fashioned, almost a form of antiquarianism. Within a decade it had declined essentially to a rich man’s hobby, and fell largely into the hands of eccentric aristocrats and wealthy sportsmen. There was a great vogue for ‘champagne ballooning’, reaching its apogee in the Edwardian period, when the famous Gordon Bennett Annual Long Distance Balloon Race was inaugurated in 1906.* Rules and clubs were formed, international cups and prizes competed for, birthdays and fashionable weddings were celebrated in the air. There was a glamorous ballooning ‘season’, as for racing, polo, or yachting. These rich amateur balloonists also enjoyed taking up literary and artistic figures on both sides of the Channel, like Guy de Maupassant or H.G. Wells, on what were essentially celebrity jaunts.

Maupassant went up in a balloon in 1887. He had printed invitation cards to the launch, as for a luncheon party, but its real purpose was to advertise the publication of his strange autobiographical novella, Le Horla. The balloon was named after the book, and the flight was an early form of publicity book tour from Paris to Belgium. Le Horla is a story of incipient madness, and Maupassant himself was already suffering from grave mental problems, from which he would die in 1893. Perhaps for that very reason the balloon flight seemed rapturous, a strangely releasing and therapeutic experience: ‘The heady perfume of cut hay, wildflowers, damp green earth rose up through the air … A profound and hitherto unknown sense of well-being flooded through me, a well-being of both mind and body, a feeling of utter carelessness, infinite repose, total forgetting …’3

H.G. Wells ingeniously used the account of a runaway balloon flight to open his futuristic novel The War in the Air (1908). His protagonist, Bert Smallways, is accidentally swept away in a hydrogen balloon from Dymchurch Sands, on the Kent coast, and travels across the Channel and all the way to Germany. Initially Bert’s sensations are euphoric: ‘To be alone in a balloon at a height of fourteen or fifteen thousand feet – and to that height Bert Smallways presently rose – is like nothing else in human experience. It is one of the supreme things possible to man. No flying machine can ever better it. It is to pass extraordinarily out of human things.’4

But it is a sign of the times that Bert’s balloon finishes up over a secret Zeppelin factory in Bavaria. He sees the future lying beneath him in the form of row upon row of ‘grazing monsters at their feed’. These are ‘huge fishlike aluminium airships’, some over a thousand feet long, each capable of ninety miles per hour into a headwind, and fully equipped with guns, bombs and ‘wireless telegraphy’. The fleet is commanded by an Admiral von Sternberg, who is described in terms of the Franco-Prussian War, as ‘the von Moltke of the War in the Air’.5 Having inadvertently observed all these modern secrets from his old-fashioned balloon, Bert Smallways is symbolically shot out of the skies by a volley of German gunfire.

What remained of serious free ballooning at the end of the nineteenth century was notable for increasingly extreme and quixotic flights. These were usually of two kinds: reckless and bizarre attempts to entertain local crowds, or else equally reckless attempts to establish some kind of world record. Such exploits were intentionally dangerous and controversial, and brought all kinds of drama and fatalities, usually accompanied by huge and sensational press coverage. Yet all but a few were quickly forgotten. It was, in a sense, the fin-de-siècle of ballooning: stylised, extravagant and gloriously picturesque, but ultimately as ephemeral as a breath of air. Yet among these strange latterday balloonists there were a small band who deserve to be remembered. They were often unearthly in their courage.

* Interrupted by both World Wars, the Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett was reinstated in 1983, and continues to this day. It is regarded as the premier free-flight gas balloon competition in the world. But it also remains perilous. In October 2010 I was at Albuquerque for the annual International Balloon Fiesta, when rumours of the disappearance of two experienced and much-loved local aeronauts, Richard Abruzzo and his co-pilot Carol Davies, began to circulate. They had won the 2004 Gordon Bennett Cup, and were the favoured crew in the 54th event, which that year launched from Bristol. They had flown southwards across the Bay of Biscay, over France, Spain and Italy, and then on the third morning turned east and started to cross over the Adriatic, between Brindisi and Serbia. Here, on 29 September, all radio contact had suddenly been lost, and no emergency beacon could be tracked. Over the next few days it gradually emerged that they had been killed in a thunderstorm when struck by lightning at five thousand feet, and had dropped like a stone into the sea. Their open gondola, still containing their bodies, was not recovered until December. I had flown and talked with some of their colleagues, and witnessed the consternation and soul-searching this terrible news caused. I was also shown the aluminium frame basket they had used on a previous prize-winning flight, proudly preserved in the Anderson-Abruzzo Albuquerque Museum. My notebook reads: ‘The yellow panelling is torn where they were thrown out on a rough landing and Richard fell thirty feet and broke his ribs and pelvis.’

In Britain, this aerial champagne culture produced an extraordinary late fashion for female balloon acrobats and trapeze artists. This was a risqué tradition that had hitherto been largely confined to France, and the spectacular performances of the Garnerin and the Godard girls. Now it appeared in England, a striking demonstration of the fin de siècle of ballooning.

illustration credit ill.161

Dozens of celebrity female aeronauts and artistes began performing at county fairs and festivals across the land, executing acrobatics, releasing aerial firework displays, or doing parachute jumps, in a tradition that went right back to Sophie Blanchard. Many of them are only remembered by a few colourful posters that have survived in provincial museums, announcing their promised aerial feats, in sixty-point letterpress and garish red, green and gold illustrations.

Posters can still be found that announce ‘Miss Marie Merton’s ascent’ at Wolverhampton fairground in 1891. Or newspapers that advertise Maude Brooks and Cissy Kent as ‘the stars of Lieutenant Lempriere’s Aerial Show’. A poster declares that on 2 June 1891 ‘Miss Maude Brooks will Drop from the Clouds’ at the Cricket Grounds, Rotherham, in South Yorkshire: ‘She will endeavour to alight within the Grounds, but in the event of not doing so, will return with all possible speed, appear on stage, and give an account of her Aerial Voyage.’

These performances were not as frothy and light-hearted as they seem. Maude Brooks was seriously injured when her balloon collapsed during an ascent from a Dublin garden party on 25 May 1893. She managed to release her parachute, but fifty feet above the ground it tore and she landed heavily, breaking her legs and arms, and permanently damaging her spine. Such threats of death or injury hung over all of these aeronauts.6

illustration credit ill.162

Perhaps the most famous Edwardian balloon girl was twenty-year-old Dolly Shepherd. Flying regularly from the Alexandra Palace, and fairgrounds all over England, she popularised a truly terrifying balloon act in which she ascended several thousand feet hanging beneath a trapeze, then pulled a simple release cord and dropped back to earth by parachute. Dolly used no balloon basket at all, but hung fully exposed from her trapeze bar, dressed in a blue-trousered flying suit, with a jaunty cap and tight lace-up boots to show off her legs. Her only instrumentation was a tiny altimeter, which she wore as a silver bangle on her left wrist. She had many male admirers, and received several offers of marriage. But she had an even greater following among young working-class women, who regarded her as a portent of women’s rights.

In 1908 Dolly gained a national reputation when she ascended on twin-parachute harnesses with her friend Louie May. When Louie’s harness failed to release at twelve thousand feet, Dolly performed the extraordinary feet of transferring the petrified Louie to her own trapeze, while still attached to the balloon. She then pulled her own parachute release, which worked, and with Louie’s arms locked around her neck, brought them both safely back to earth on a single parachute. Louie was unhurt, but Dolly suffered severe back injuries which left her paralysed in a wheelchair for many weeks. Astonishingly, she recovered, and continued balloon parachuting for several years afterwards.7

illustration credit ill.163

It was an exceptional act of courage and, above all perhaps, of female friendship. Yet many felt that Dolly was being exploited by her balloon Svengali, a mysterious Frenchman known simply as ‘Captain Gaudron’. He arranged all her flights, supplied her equipment (including her provocative uniform, and also the release mechanism that failed), but only paid her piecemeal, by each ascent, and certainly without any life insurance. Yet Dolly would always speak with a naïve rapture, and a certain nostalgia, of her balloon experiences. Her passionate attitude seems expressive of this late period of extreme risk-taking.

I never lost that sense of wonderment and ecstasy whenever I floated alone in the awesome silence … Every ascent renewed in me those same feelings of delight and contentment. When I soared upwards, above all earthly worries and discomforts, my mind was set free to wander at will and to absorb the sensations of gentle flight, and the beauty of everything around and below me. I never failed to marvel at my bird’s eye view of the scenes below, whether rural or urban, forming an intricately woven tapestry above which I floated so effortlessly. In those days, flight in any form was an experience known to only a very few of us. Remember, no aeroplane flew in England until 1908.8

What was the appeal of these hugely popular and sensational displays? As the parachutes were still relatively crude, and the balloons increasingly old and ill-maintained, the performances were always far more dangerous than the sporting, fairground atmosphere suggests. Frequent injuries and regular fatalities occurred, as also happened in the Edwardian circus. According to Dolly, most of the parachutists with whom she worked, even the most glamorous ones such as Maude Brooks or ‘Devil-may-care Captain Smith or handsome dashing Captain Fleet’, somehow ‘disappeared’, as she put it in her memoirs.9

They may have been killed, but the more sinister possibility is that, like her, they suffered spinal or internal injuries as a result of a crash or a heavy landing. But unlike Dolly, they may have been paralysed or disabled for life. There was no attempt to regulate or license the displays, let alone to insure the lives of the performers, until the First World War brought such frivolities to an end. Nevertheless, like their contemporaries the suffragettes, many of them, such as Dolly, insisted that they were striking a blow for women’s freedom.

These young aerial artistes, so dazzling in their courage and carelessness, were some of the last representatives of the great nineteenth-century tradition of ballooning as entertainment. They were both the stars and the victims of the show, and it would be difficult to judge how far they were liberated or exploited in their métier. Like beautiful sacrifices they would be ‘offered up to heaven’; and like angels they would ‘drop back from the clouds’ for the edification of casual onlookers. Remarkably, such displays continued in America into the 1930s. But strangely, the ambiguity of their roles was mirrored in the other form of extreme ballooning.

The outstanding example of the extreme record-breaking balloonist was the Swedish engineer Salomon Andrée, and his fantastic efforts to reach the North Pole by balloon in 1896–97.

illustration credit ill.164

Andrée was born in 1854 in the tiny provincial township of Gränna, three hundred miles south-west of Stockholm, on the edge of Lake Vättern. He was brought up largely by his mother, Wilhelmina; his father, an apothecary, died when he was sixteen. As a boy Salomon ran wild, building rafts, sailing boats and on one occasion launching a fire balloon that set light to a local barn. He remained close to his mother all his life, calling her Mina, and sending her long letters confiding in her all his plans and secret ambitions. She seems to have given him an inner confidence and self-sufficiency that never left him. He grew up exceptionally tall, headstrong and adventurous, and defiant in his attitudes. He was strongly committed to the natural sciences, with a special fascination for engineering, meteorology and ornithology. By contrast, he disclaimed all interest in the arts and literature, claiming that concerts and art galleries bored him, and that he only liked adventure stories – notably the fantastic tales of Baron Munchausen.10 Like a hero out of Jules Verne – or Nietzsche – his watchword became ‘Mankind is only half awake!’

Andrée trained at the Royal Institute of Technology, Oslo, where he graduated with a first-class degree in engineering, and a passionate belief in the power of ‘technology’ to solve human problems. This engineering degree was itself a recent innovation, with particular attention paid to all forms of transport, including railways, engines and bridge constructions. Immediately on graduation, at the age of twenty-two, Andrée characteristically decided to visit the future, and travelled steerage to America, landing in New York with little money, no contacts and no work in prospect. Undaunted, he took the railroad south to the home of American science, Philadelphia. He arrived in time (probably as he had planned) for the Philadelphia International Exhibition of summer 1876, and enthusiastically toured all the stands, making notes of all the new mechanical inventions. To his delight he came upon a Swedish national stand, and at once succeeded in landing himself a job as a demonstrator and technical assistant for the duration. He also had his first glimpse of the importance of publicity and clever presentation in getting innovative projects ‘off the ground’ – a significant new American catchphrase.

But something unexpected occurred during these formative weeks. Andrée sought out not contemporary engineers and railroad designers, but the legendary old American balloonist John Wise, now retired (temporarily) at ground level on the east coast. They talked of the American dream of the Atlantic balloon crossing, and the theory of prevailing high-altitude currents. They may even have talked of ballooning to the Pole, since Wise published a letter on this very subject three years later in the New York Times.11

Young Andrée became fascinated by the technical challenge of ballooning. Wise recommended the latest works on meteorology and trade-wind patterns, and promised to take his young Swedish protégé on an introductory flight once the Exhibition was over. Twice Andrée climbed into one of Wise’s balloon baskets, but twice Wise cancelled the flight at the last moment due to bad weather conditions, a lesson in prudence that Andrée did not perhaps fully appreciate at the time. To his infinite frustration, Andrée never actually flew with John Wise in America, though in later years he sometimes implied that he had, the old American master handing on the aeronautical baton to the young Scandinavian one.

Returning home, Andrée obtained a post in the Swedish Patent Office, where he could study the development of every kind of mechanical invention, but he remained restive and unfulfilled. In 1882 he made another daring career leap, and volunteered for a two-year scientific expedition to the bleak northern island of Spitsbergen. This was a remote, icebound territory claimed by Sweden, lying inside the Arctic Circle between 78 and 80 degrees north. Hitherto quite unexplored, except by passing whalers, Spitsbergen was fast becoming the new Swedish centre for the science of polar exploration. There was growing rivalry with the Norwegians, who had discovered Franz Josef Land to the east in 1873. At this time neither Pole had been reached, and numerous expeditions – like that of Sir John Franklin to discover the North-West Passage in 1845 – had been lost, always under terrible conditions, including snow-blindness, limbs amputated as a result of frostbite, and rumours of cannibalism. There was much speculation about the unknown icy extremes at either end of the planet. Were they simply frozen deserts, or were they inhabited by unknown tribes, or even by unknown monsters? The great Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen wrote at this time: ‘The history of polar exploration is a single mighty manifestation of the power of the unknown over the mind of man.’12

The North Pole was particularly mysterious, with a powerful symbolic presence in Icelandic literature, and in such works as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), whose terrible dénouement takes place on the frozen Arctic Ocean. No one knew if the ice pack eventually became land, and if so what kind of creatures – besides the enormous and ferocious polar bear – might live there. Unlike the South Pole, the North Pole itself had no land mass or definable landmark, but was merely a geographical coordinate at 90 degrees north on the frozen ice cap. No expedition had reached further north than 83 degrees and survived to tell the tale. Using sledges, the English explorer William Edward Parry had got less than a hundred miles beyond Spitsbergen to 82.45 north in 1827, and the Royal Navy Commander Albert Markham had pushed to 83.20 north in 1876. But two American expeditions, led by Charles Hall (1871) and George DeLong (1881), had ended in disaster.

On Spitsbergen Andrée’s determination and independence greatly impressed the expedition’s director, Dr Nils Ekholm, who then held the important position of Senior Researcher at the Swedish Meteorological Central Office. Ekholm saw Andrée as a natural leader, with immense technical confidence. On his return to Sweden, Andrée began specialising in meteorology, and published several successful academic papers during the 1880s on electrical charges in clouds, and polar winds and weather patterns. He gained a reputation as a polar expert, and gradually the idea of mounting his own polar expedition from Spitsbergen began to possess his imagination.

Against this was the possibility of a more conventional, domestic future. Throughout his thirties Andrée had a long-term liaison with a married woman, Gurli Linder. She was deeply attached to him, and considered divorce; but perhaps her married status suited Andrée.13 He used to say that ‘marriage was too great a risk’ for an explorer, and that his mother remained his closest confidante. He seems to have been curiously aloof and inexpressive in most of his friendships, although he had a natural gift with children, and would unbend and join in all their games with boyish enthusiasm, ‘frolicsome and roguish’.14 But more and more he became obsessed by finding a brilliant engineering solution to what he thought of as ‘the challenge’ of the North Pole.

The infinitely slow and wearisome traditional method of Arctic travel by dog sledge, or skis, or drifting boat, seemed absurd to Andrée. He thought of John Wise and the great American dreams of epic flight. Slowly the decisive project took shape. The modern engineering solution to the North Pole was clearly air travel. Surely it would be possible to fly there in a specially designed and engineered hydrogen balloon? He could ‘conquer’ the Pole simply by dropping from the skies, anchoring at 90 degrees north, and depositing a Swedish flag and a marker buoy. It would be the ultimate, planetary, record-breaking balloon flight, before the nineteenth century came to an end. Andrée felt he had taken on a national destiny. Marriage would have to wait. He spent the next six years totally dedicated to technical preparation, publicity and fund-raising.

Andrée took his first actual flight in a balloon surprisingly late, two years into his project, in summer 1892, having hired the Norwegian aeronaut Francesco Cetti, based in Stockholm, to teach him. Cetti described Andrée as ‘disagreeably calm’ when airborne, and impervious to the picturesque charms of ballooning. Instead he was excited by all the technical potential the balloon offered, notably the use of onboard cameras, and the possibility of mapping a large swathe of the unexplored Arctic with overlapping photographs. On the strength of such ideas, he managed to raise funds for his own first experimental balloon. This was a relatively small 37,230-cubic-feet aerostat, which he named Svea, after the national emblem, the fierce valkyrie Mother Sweden, tutelary goddess of the North. It was the first of many skilful publicity gestures.15

Between 1893 and 1895 he made eight short flights aboard the Svea in Sweden, all undertaken solo and without further training from Cetti. He proved a natural aeronaut, cool and resourceful, and was soon experimenting with various forms of baskets, instrumentation, sails and drag lines. On his third flight, in October 1893, he was caught in a violent storm and blown out to sea from Gothenburg, and right across the Baltic towards Finland. He should have been lost, but keeping his head, he skilfully crash-landed on an offshore island, jumped from the basket, and allowed the tattered remains of the Svea to blow away without him. They were eventually found fifty miles away on the Finnish mainland.

Because he was missing for forty-eight hours, Andrée attracted a great deal of publicity in the Swedish press, and the disaster was turned into a triumph. A crowd of three thousand people greeted him on his return to Stockholm aboard a Finnish steamer. His tall, Viking-like figure, with his thatch of blond hair and large, dashing moustaches became increasingly well known. On his last flight in the Svea he travelled 240 miles in little over three hours, and successfully used a rip-panel to land. He could now claim to be Sweden’s leading aeronaut, although in reality his total flying experience amounted to about forty hours in the air.

Andrée published his flight reports in the Royal Swedish Academy Journal, and gained the powerful support of the leading polar scientist A.E. Nordenskiöld. Building upon this, he shrewdly publicised his new method of steering the balloon, by combining a special type of drag rope with a newly designed sail. With such engineering innovations, Andrée caught the attention of the popular press, while simultaneously promoting scientific fund-raising. At academic sessions his gaunt, aristocratic appearance, sober and even melancholy, gave him natural charisma and authority.

He did not seem like an adventurer, though he was quick to spot opportunities. During one meeting of the Academy, Nordenskiöld raised the possibility of a ‘photometric survey’ of the Arctic from a fixed balloon, tethered at Spitsbergen. Andrée cleverly ran with this as a brilliant idea, though he had already conceived it himself, and merely added that it would be even better for the Academy to fund a free balloon, because then the survey could go as far as the Pole itself. Nordenskiöld was delighted with this response.16 During the 1890s Andrée assembled serious scientific support for such a perilous and even quixotic expedition, and gained several wealthy patrons, including the great industrialist and arms manufacturer Alfred Nobel.

It helped him that polar exploration was increasingly in the news, and a question of national pride. In summer 1894 Nansen set out on his famous expedition to get as near as possible to the North Pole by drifting in the ice floes in his specially constructed boat the Fram. Nansen planned to overwinter on his journey, and somehow survive the six months of total polar night. He set out, amidst much Norwegian excitement, but failed to reappear in the summer of 1895. Nothing was heard of his expedition for the next twelve months. When he failed to return in the spring of 1896, a rival Swedish expedition seemed appropriate. Finally King Oscar II, monarch of both Scandinavian countries, expressed his approval of Andrée’s attempt to ‘conquer’ the North Pole by the latest technical means, and made a substantial donation. Exactly as Andrée had planned, his balloon expedition had become a patriotic endeavour.

Andrée now hastened to put together a balloon crew. Shrewdly he first persuaded his erstwhile meteorological director, Dr Nils Ekholm, then in his late forties, to agree to accompany him. His professorial, bespectacled appearance somehow further increased the expedition’s scientific standing. A second potential member of the crew was Ekholm’s brilliant young assistant Nils Strindberg. Aged only twenty-four, Strindberg was a trained physicist and meteorologist, but also had wide interests in books and music. He drew, painted and played the violin. His family were prosperous and distinguished, and he was a nephew of the great dramatist August Strindberg.

This was another shrewd choice. Temperamentally the opposite of Andrée, Strindberg was a cheery and attractive figure, bubbling with life and fun, adding a good emotional balance to the team. He was disarmingly youthful in appearance, and soon attempted to cultivate an unconvincing Andrée-style moustache. Yet equally vital for the expedition, he had already made a name for himself as an open-air photographer, using the latest Eastman Kodak equipment. In this capacity he further enhanced the engineering credentials of Andrée’s crew. Like Ekholm he knew nothing at all about balloons. But unlike Ekholm, he characteristically hurried over to Paris to take aeronautical lessons, which he regarded as a ‘tremendous lark’.

Andrée formally presented his scheme, ‘A Plan to Reach the North Pole by Balloon’, in a long and masterful speech given first to the Swedish Royal Academy in Stockholm in February 1895, and then repeated to the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London the following spring.17 In his best dry, commanding manner he outlined the apparently overwhelming challenges posed by an Arctic balloon flight. In sum there were four huge problems: how to sustain the balloon in the air for at least thirty days; how to survive the extreme cold and the potentially fatal problems of icing; how to navigate the balloon on a continuous northerly course; and how to get home in the eventuality that the balloon came down on the ice.18

illustration credit ill.165

Then, one by one, he coolly analysed each of these formidable difficulties, giving his own precise technical answers. His central theme was that reaching the North Pole was no longer ‘a purely scientific problem’, or even a human problem. It had become a specifically technological problem, a straightforward ‘task for the technologist’ requiring a logical series of engineering solutions.19 He could provide these with a package of brilliant inventions, ranging from an adaptable sailing rig, adjustable guide ropes, self-venting gas valves and ice-repellent balloon fabrics, to the smallest practical details, like an insulated cooking device, lightweight aluminium cutlery, and tinned condensed milk.

Many of Andrée’s larger claims would turn out to be chimerical, but it was an extraordinary and captivating performance just the same. Not least because he sounded almost exactly like one of Jules Verne’s fictional heroes, solemnly proposing ‘An Aerial Excursion Across the Icy Continent’ at some packed and breathless meeting of the Royal Geographical Society. It was as if the final destiny of nineteenth-century ballooning was to inflate fiction into fact (or indeed, vice versa).

Two great polar explorers, the American General Adolphus Greely and the British Admiral Sir Albert Markham (whose cousin Sir Clements Markham would later champion Scott’s two expeditions to the Antarctic), were in attendance at Andrée’s London talk, and gave a guarded welcome to the project. By contrast, Nansen’s Fram scheme had been universally criticised when presented to the Royal Geographical Society three years previously.

Although he did not actually mention Verne, it is clear from later references in his papers and diaries that Andrée saw himself as fulfilling the destiny of the whole previous century of historic ballooning. He would mention Pilâtre de Rozier’s pioneering ascents in France; Charles Green’s night flight across Europe; John Wise’s dream of crossing the Atlantic; James Glaisher’s heroic attempt to explore the seven-mile altitude limit; the intrepid flights of the Paris siege aeronauts (and notably the flight that ended in Norway); Wilfrid de Fonvielle’s bucolic five-day cross-country flights, anchoring the balloon each night; and the strange apotheosis of Henri Giffard’s gigantic captive balloon at the Paris Exhibition, like some ancient heroic god shackled by a race of modern industrial pygmies.

Perhaps the most extraordinary blurring of fact and fiction occurred in the time frames that Andrée proposed for his polar expedition. His hydrogen balloon would be capable of staying aloft for at least a month, a feat never remotely approached by any previous balloon. It would be capable of carrying crew supplies and equipment that would last for at least three months, an equally astonishing boast. Moreover, it would be dirigible throughout the journey, both to the Pole and away from it, a highly contentious claim. Yet, paradoxically, the actual journey time from Spitsbergen to the Pole, a distance of some 660 nautical miles, would be amazingly short.

Andrée gravely proposed three possible time scales, all ‘scientifically calculated’ according to previous flight data. The first was based on the speed of the famous siege balloon of November 1870, that reached Norway from Paris in fifteen hours. Based on this balloon’s velocity, Andrée projected that the North Pole could be reached from the Spitsbergen area in an astonishing six to eight hours. The second time scale, based on Andrée’s own crossing of the Baltic in the Svea during the storm of 1893, would occupy ‘little more than ten hours’.20 Both of these figures made the crossing of the huge, fearful Arctic ice cap sound like a walk in the park. His audience was reduced to amazed silence.

The third projected schedule was perhaps a little more realistic. It was based on the meteorological records Andrée had himself taken at Spitsbergen during previous Arctic summers. He claimed that these revealed the existence of one of those largely regular and reliable ‘oceanic air currents’ of seasonal wind, which the great aeronaut John Wise and others had predicted. He believed that just such an oceanic current, a regular north-moving low-pressure cyclone, did indeed exist in the Arctic summer. It promised ‘an average steady 16.2-mile-per-hour breeze’ to the north, starting in June, which if unbroken would carry the balloon to the Pole in ‘approximately forty-three hours’. This would be just under two days and two nights (except that in the northern summer there would be no nights). Andrée considered this time frame, between forty and fifty hours of travel, the most likely and also the most practical. It would allow proper time for observations, meals, sleep and carrying out a full photometric survey with ‘2 photographic apparatus and 3,000 plates etc’.21 *

The one thing that Andrée’s time projections did not include was how long, or which direction, the balloon would take to return from the Pole, although he did optimistically suggest that a journey from Spitsbergen directly across the Pole to the Bering Strait, a distance of 2,200 miles, might take a mere six days – ‘that is, one-fifth of the time during which the balloon can remain in the air’.22 He pointed out, with a rare smile, that once one had reached 90 degrees north, any direction was southwards, and therefore homewards: either towards Russian Siberia, or Canada, or Alaska, Iceland or even Greenland. Wherever one landed, he suggested, the Swedish pioneers would be greeted as aerial citizens of the world.

The balloon he presented was confidently christened the North Pole. Intended as the last word in aeronautical engineering, it was simultaneously a kind of Vernian fantasy machine. Two hundred and twelve thousand cubic feet (about the same size as Nadar’s Le Géant), standing ninety-seven feet tall and sixty-seven feet in diameter, it was constructed from three layers of hugely expensive double Chinese silk, and protected from ice by a special varnished cotton top canopy or calotte. Its venting valves were placed at the side of the balloon, rather than at the top, to prevent them icing shut. The conventional open neck above the basket was replaced by an automatic pressure valve, adapted from one designed by Giffard.23

The North Pole had an overall lifting capacity of 6,600 pounds (approximately three tons), of which three thousand pounds was free ballast in various forms. Of this, its complex system of three one-thousand-foot trail ropes, and eight shorter ballast ropes, provided 1,600 pounds – almost half – of the total adjustable ballast. So the ropes were crucial to its equilibrium. Altogether Andrée claimed to have designed into the balloon a large theoretical safety margin, allowing him to adjust altitude, and to respond freely to the expansion or contraction of hydrogen due to temperature changes in the Arctic air. Yet, apart from the calotte, he largely ignored the problems of moisture, Arctic fog and icing.24

The payload elements of the aerostat were mounted in three special sections, one above the other, suspended from the main balloon ropes. They consisted of a closed crew basket, then an open observation deck, and finally – above the balloon hoop – a conic or circular storage section. This arrangement had never been tried, or even tested before, but was intended to demonstrate all Andrée’s technical skill and foresight.

At the base was the specially insulated and enclosed wicker basket, six and a half feet in diameter and five feet in depth, ergonomically designed rather like a yacht’s cabin. Unlike conventional balloon baskets, it was sealed at the top with a flat roof, and accessed by a narrow hatch. Within, padded compartments were crammed with the latest scientific instruments, including chronometers, compasses, sextants, barometers, message buoys, and three pairs of Zeiss binoculars. Unusually for a balloon, it had a sleeping bunk, a galley and a night-stool. Typical of Andrée’s ingenuity was a mobile spirit cooker and oven, which could be lowered beneath the basket to prevent the risk of fire, and lit by remote control.

Stores included three months’ worth of tinned food, rifles and ammunition, fishing gear, a Swedish flag, and a reindeer-skin sleeping bag, large enough to take all three crew. This three-man sleeping bag was characteristic of the Scandinavian approach to Arctic exploration. It assumed teamwork, good fellowship, and the practical value of shared body heat. There were also marker buoys, thirty carrier pigeons, and numerous luxury items including champagne and Belgian chocolates.

The second section was the circular observation deck. This was effectively formed by the flat roof of the basket. Again, it was the equivalent of a yacht’s cockpit, encircled by an adjustable canvas windshield or ‘dodger’, and protected by a chest-high wooden railing. The railing was an Andrée invention, known as the ‘instrument ring’, upon which a variety of observational instruments – cameras, barometers, ground-speed calculators – could be quickly bolted or unbolted as required. Such a deck, combined with the enclosed basket, meant that separate ‘watches’ could be kept, and the crew could take turns to go below to sleep or eat or write their journals, a vital consideration for morale on a long journey. Although of course the journey out was only intended to last fifty hours.

The third section was mounted, in another design innovation, above the balloon hoop, and accessed through the hoop by a rope ladder. It consisted of carefully selected packs of back-up supplies, stored in a system of canvas pockets and sealed compartments. Most of them were only intended for use if the balloon came down. Apart from further stores and ammunition, notable additions were a tent, a surprisingly large collapsible boat with paddles, and three self-assembly wooden sledges. These were Andrée’s solution to any enforced landing on the ice.

Andrée’s greatest ingenuity had been reserved for his special guidance system. This consisted of three sails, in combination with the series of heavy guide and ballast ropes. The sails were mounted on a horizontal bamboo boom slung from the balloon hoop, like the topsails of a square-rigged ship. The three main hemp guide ropes, each over a thousand feet long, were slung from a hand-cranked winch that could pay them out or haul them back in again. When fully extended along the ice, they would drag and act as a kind of counterweight against the pull of the wind. In case they jammed in a crevasse or ice snag, Andrée had ingeniously fitted each section with exploding break points, and also with unscrewable metal disconnectors.

illustration credit ill.166

By slightly slowing the balloon down, the guide ropes radically changed its aerodynamics, making it behave like a kite held by someone running along the ground, or a sailing boat with its keel running through water. Thus Andrée believed that he had found a way of giving balloon sails a vital purchase on the airflow.

Additionally, in a brilliantly simple device, the angle of the trailing ropes relative to the balloon could be altered by running them through a heavy wooden swivelling block. Again, this was a design taken from sailing ships. The effect was to twist the balloon relative to the airflow, thereby automatically turning and altering the setting of the sails. Thus, by simply adjusting the angle at which the guide ropes left the balloon through the swivelling block, the sails could be turned to act like an airborne rudder. So Andrée believed he could redirect the course of his great balloon.

With this method, convincingly illustrated by fine engineering drawings, Andrée informed the Swedish Royal Academy that he could steer his balloon off the line of the wind by as much as twenty-seven, or even forty, degrees.25 If his projected ‘light Arctic breeze’ deviated to the east or the west, he could bring the balloon back on a true northerly course with a simple adjustment of his swivelling block. Thus Salomon Andrée claimed at last to have solved a problem that had haunted aeronautics for almost exactly a hundred years. He had designed a self-sufficient, long-distance, dirigible free-flight balloon.

The North Pole was different from all previous free-flight balloons in one other crucial respect: it had a very narrow altitude band. In order to be dirigible, it always had to remain close to the ground, so its ballast and guide ropes would work. Andrée stressed: ‘The weight of the balloon must be so balanced that when free it will stay at an average height of about eight hundred feet above the surface of the earth: viz. below the lowest region of clouds, but above the mists close to the ground.’26 Accordingly, unlike conventional hydrogen balloons, the balloon envelope was fully inflated to keep it within this critical altitude band. It had little space for expansion. It would immediately vent gas through its automatic Giffard valve if it rose much beyond a thousand feet. So if, for any reason, it did rise higher, then gas would be lost and very large amounts of ballast would have to be abandoned to re-establish its equilibrium or balance. As ballast equalled flying time, it was a design innovation with unknown implications.

Of course, apart from some early prototype journeys in the little Svea, Andrée had hardly flight-tested any of these innovations. Most of them remained brilliant drawing-board ideas. Yet the whole project was modestly presented to the Swedish Academy as a logical exercise in practical engineering. Some critics wondered if this was not after all merely a version of techniques tried out many times before, and many years ago. Hadn’t Charles Green tried guide ropes? And even before that, hadn’t Blanchard tried sails? Was it an old fantasy, rather than a new technology?

Yet Andrée’s calm authority, his ‘scientific data’, and perhaps his commanding moustache, quietly carried the day. Moreover, in his peroration he emphasised patriotic destiny, and gently mocked the attempts of the Norwegians, led by Nansen, who was still missing in the Fram: ‘Who, I ask, is better qualified to make such an attempt than we Swedes?…Is it not more probable that we shall succeed in sailing to the Pole with a good balloon, than that we shall reach it with sledges for transport … or with boats that are carried like erratic blocks, frozen fast to some wandering masses of ice?’27

Accordingly the North Pole was funded, and swiftly built. Amid immense publicity, Andrée and his crew sailed to Spitsbergen aboard the Virgo in June 1896, accompanied by a small fleet of well-wishers, scientists and press. A crowd of forty thousand people saw him off from Stockholm docks. His mass of equipment, all of it proudly engraved or marked in red paint with ‘Andrées Pol. Exp. 1896’, was unloaded in a shingle cove on the north-western tip of Dane’s Island. A huge wooden balloon hangar and a hydrogen-generating shed were swiftly constructed. Within four weeks the immense balloon was successfully inflated, and all the equipment prepared. The weather was fine and mild, perfect for a launch. But the wind blew steadily and provokingly from the north, not towards it.

They settled down to wait for Andrée’s predicted light southerly cyclone breeze. It never came. Andrée gave endless press briefings, several tourist steamers came and went, the great balloon stirred uneasily in its wooden cage, and the Arctic air was suspiciously perfumed with escaping hydrogen. At the end of August, after two frustrating months, the whole expedition had to return to Sweden. Just before they left Spitsbergen, Nansen’s ship Fram sailed quietly into the bay.

* Andrée’s idea of a ‘photometric survey’ of the Arctic was not ill-conceived. It eventually led to continuous high-altitude surveys of the Arctic ice cap, beginning with NASA’s ‘Scanning Multichannel Microwave Radiometer’ (SMMR) satellite in 1978. These first showed the huge seasonal expansion and contraction of the Arctic ice field, though not the thickness of the ice. It appears that the volume of summer Arctic ice has contracted by approximately 50 per cent since the year 2000, though the re-freeze of the ice cap in winter has remained roughly stable. These summer contractions or meltings were particularly noticeable in 2007 and 2012. Model predictions suggest that there may be no summer ice cap at all by 2030. The cause of this may be part of a natural cycle (the end of the so-called ‘4th ice age’), or directly attributable to man-made global warming, or both. Either way, such shrinking, if continuous, would probably affect the Gulf Stream and the whole weather system of Great Britain and northern Europe. It would make it less temperate and more extreme, in storms, heatwaves and droughts. See ‘Arctic Sea Ice’ on NASA’s Earth Observatory internet site. André’s fellow Scandinavian scientists were already considering such possibilities.

It was a strange and bitter anticlimax. Andrée stoically hid his disappointment, but was secretly devastated when Nansen himself triumphantly returned to Norway in September, having twice overwintered on the ice. In the first year the Fram had reached above 84 degrees north; and in the second, Nansen had set out with dog sledges from the Fram and had reached 86 degrees 14 minutes north, a formidable achievement, within a hundred miles of the Pole. Afterwards, Nansen and his colleague Hjalmar Johansen had succeeded in walking home together through the terrible pack ice, on the way surviving a second winter in a tiny ice-hut built on Franz Josef Island. It was a masterly demonstration of courage, comradeship and polar skills. Nansen recounted the trek in a superbly written travelogue, Farthest North (1897), which is still a bestseller.

Inevitably, Nansen stole much of Andrée’s thunder with the Swedish public. Worse, he had inadvertently raised the bar for any future polar expedition, which would inevitably be regarded as a failure unless it penetrated well beyond 86 degrees north. Andrée briskly announced that he would try again in summer 1897, but support for the renewed expedition naturally wavered. Alfred Nobel continued his subsidy, and so did King Oscar, but there was growing criticism in the press. Was Andrée really a fantasist, a dreamer? Was his huge balloon a ludicrous anachronism?

Dr Nils Ekholm, Andrée’s senior partner, now privately questioned him over the durability of the balloon fabric. He calculated that the balloon canopy, even while tethered in Spitsbergen, had been losing about 120 pounds of lift per day. In his view, this reduced the balloon’s endurance in the air from thirty days (by the end of which time he projected it would have lost more than its entire lifting capacity of six thousand pounds) to an absolute maximum of seventeen days, and probably much less. Andrée agreed to increase the size of the balloon by sewing in new gores, but at Christmas 1896 Ekholm officially resigned from the 1897 expedition. He had lost faith in Andrée’s dream.

Ekholm later published further reasons for resigning. They were revealing. He believed that Andrée had also lost confidence in the balloon’s endurance, and its capacity to complete the whole expedition in the air. The vague talk of flying on over the polar ice cap to Greenland, Alaska or Siberia (depending on the wind direction) was a chimera. The balloon flight was a one-way ticket. He thought Andrée was secretly resigned to coming back the hard way, by sledge and boat. There was no ‘engineering solution’ to this. It would be a brutal, slogging, potentially suicidal journey of up to six hundred miles. Even the experienced and hardened Nansen had taken two years to accomplish it, and had been forced to winter on the ice. Ekholm, who was now forty-eight, did not think he was physically capable of such a trek, and he doubted if Andrée was either. He especially feared for young Strindberg. He summed up Andrée’s dilemma as simply as possible. The balloon must have the scientifically proven capacity ‘not merely to carry the expedition safely into the Polar area; but also safely out of it’.28 *

As for Nils Strindberg, his position was also altered. In October 1896 he had become engaged to his childhood sweetheart, a beautiful young woman called Anna Charlier. Both Strindberg’s father and the Charlier family begged him to resign from the second expedition, as did his mentor Dr Ekholm. But Anna, deeply in love, understood Nils’s desire to make his mark in science before he settled down to family life. So she supported his decision, though with deep secret misgivings.

illustration credit ill.167

Meanwhile, Andrée purchased two of the latest Carl Zeiss cameras, reminding Nils that the ‘photometric survey’ of the Arctic from the air would be a scientific first, quite unlike anything achieved by Nansen. Much torn in his loyalties, both emotional and scientific, Nils eventually decided that honour required him to continue with the second expedition.

In spring 1897, after interviewing many candidates, Andrée replaced Dr Ekholm with Knut Fraenkel, a much younger man and a very different type. This choice may have confirmed Ekholm in his worries about the nature of the journey being undertaken. Like Andrée, Fraenkel was an engineering graduate of the Royal Technical Institute, but his main accomplishments were athletic. A youthful giant of immense strength and stamina, he was a fine gymnast, a mountain climber, an adventurer who had helped in his father’s roadbuilding business in the north of Sweden. He was extroverted and good-natured, and turned out to be an excellent cook. At twenty-seven years old, he towered over the small, elegant Strindberg, and was much stockier than Andrée. But he accepted his authority, and evidently admired him far less critically than Dr Ekholm. Like Strindberg, he hurried off to learn ballooning in Paris, and despite some severe crash-landings, came back more enthusiastic than ever.

On 29 April 1897, just before the second expedition was due to sail for Spitsbergen, Andrée’s beloved mother Mina died. The loss of this most important emotional tie for Andrée, now aged forty-two and still unmarried, may in some sense have loosened his last links with the earth. When Nansen wrote him a warm letter wishing him all luck, saying how much he admired what he was undertaking for Sweden, he also sounded a note of caution, quoting Macbeth: ‘I dare do all that may become a man; who dares do more is none.’ In the most tactful way, Nansen suggested that Andrée should not allow himself to be driven to take ‘unreasonable risks’ by patriotism, or any other influence: ‘It is in drawing this boundary that true spiritual strength reveals itself.’ Like a good mountaineer, Andrée should know when to turn back; or even when not to start.29

Andrée secretly added a codicil to his will, which included an ominous sentence: ‘I write on the eve of a journey full of dangers such as history has never yet been able to show. My presentiment tells me that this terrible journey will signify my death.’30

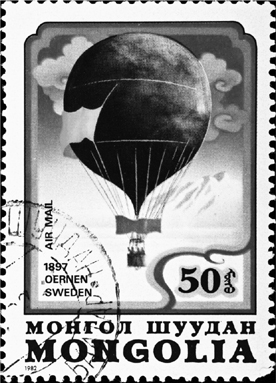

The new expedition reached Dane’s Island on 30 May 1897, repaired the balloon hangar on the bleak foreshore, and reinflated the balloon, which was now rechristened Örnen – the Eagle. Apart from this symbolic change – perhaps suggesting a triumphant flight, rather than a declared destination – all Andrée’s equipment, even his fine cotton handkerchiefs, remained emblazoned with the red insignia ‘Andrées Pol. Exp. 1896’. For nearly six weeks they waited for the wind from the south. Finally, on the morning of 11 July, the barometer dropped and a cyclone arrived, bringing low grey cloud. It blew temptingly northwards across Virgo Bay, in a series of sharp blustery squalls. The final preparations took less than four hours, and were hurried. Andrée made a point of taking both Strindberg and Fraenkel aside, and asking them individually if they agreed to launch. Strindberg was notably impatient to leave, although there was some discussion about waiting for the wind to settle its direction and strength. But after two years Andrée was not to be restrained, and ordered the downwind side of the wooden hangar to be cut away with axes. Now there was no turning back.

illustration credit ill.168

At exactly 1.43 p.m. they shook hands, released a tangle of restraining ropes, and launched the huge balloon.31 The Eagle rose with slow dignity, just cleared the hangar with a slight bump, then sailed magnificently out across the grey, choppy waters of the bay, heading a perfect due north. Everyone cheered and waved. The navigation sail was already billowing, though the complex cluster of trailing guide ropes made the balloon look curiously awkward. One of the journalists remarked that it was more like a long-legged spider than a soaring eagle. A photograph records this iconic moment, and was later enhanced as a photo-illustration that was published by Life magazine, and around the world.

illustration credit ill.169

Then, in a few seconds, the mood shifted. It was noticed that the balloon was flying very low, at little more than sixty feet. The ropes dragged a broad wake of dark disturbed water behind it, but several of them appeared to be dropping away. What no photograph showed is what had happened in the first sixty seconds of the flight. As the Eagle rose, the lower sections of the guide ropes had begun untwisting their metal screw connectors. Even before the ends reached the water, they fell with a rattle onto the foreshore.

It was later found that the ropes had been coiled neatly on the ground outside the hangar, rather than stretched out straight along the shingle. They had simply twisted round and round as they were pulled into the air, and finally disconnected themselves. It was a classic case of a brilliant technical design failing at its first practical application. A workman saw this with a shout, but Andrée did not discover it until some minutes later, as he was already preoccupied with something else.

The Eagle was failing to rise any higher. Slowly it began to dip towards the surface of the bay. Within a few hundred yards the basket was skimming and catching the water. Clearly the hurried ‘weighing off’ inside the protected hangar did not correspond to the blustery conditions outside. Ironically, the huge, powerful Eagle had not been released with enough initial lift. For a moment this seemed quite playful, and the workmen back on the shore still cheered. But in a few more seconds the basket was kicking up a bow wave, sinking deeper into the icy sea, and looking as if it would actually submerge. Alarmed, Andrée ordered a quick offload of ballast. In the emergency it seems that his two inexperienced crew, eager to obey their commander, immediately threw out four bags of gravel each, far more than necessary.

illustration credit ill.170

The Eagle was seen to jerk sharply, then leap clear of the waves and sail upwards, streaming water and trailing its shortened guide ropes high into the air. The workmen cheered again. It was only then that Andrée could see that he had lost most of his vital navigation system in the first few moments of the launch. The balloon soon rose over the coastal hills, and disappeared from sight, still climbing. Eventually it reached over two thousand feet, far higher than Andrée had ever intended to fly, and the automatic Giffard valve began releasing gas. Below them they could see the first ‘finely divided’ ice floes and the ‘beautiful dark-blue colouring’ of the Arctic Ocean. Just before they left the northernmost tip of Spitsbergen, Strindberg dropped a departure message for Anna Charlier in a canister. It was never found.

illustration credit ill.171

* Ekholm always maintained his interest in aerial exploration, but he saw that the future lay with the heavier-than-air machine, and became the founding chairman of the Swedish Aeronautical Society in 1900. Nevertheless, he still believed, like Glaisher, that crucial meteorological data could be gathered from high-altitude balloons. In addition to his work at the Swedish Meteorological Office, he continued to publish scientific papers. His visionary paper ‘On the variations of the climate of the geological and historical past and their causes’ was published in January 1901 by the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. It was one of the earliest academic papers to predict that increased CO2 emissions, both natural and man-made, would eventually produce global warming. However, Ekholm argued that this would broadly be beneficial to mankind, and would ward off the threat of a new Ice Age. See ‘On Variations of the Climate’ on the Nils Ekholm internet site.

From now on the history of the expedition has four main written sources, which do not always tell quite the same story. The primary one is Andrée’s official diary, which is in effect the captain’s log. The next is Fraenkel’s logbook, which consists mainly of meteorological observations. The third and fourth are Nils Strindberg’s almanac, which mixes navigational with private records, and finally Nils’s extended love letter to Anna, nine pages written in shorthand, which he intended to deliver on his return as a form of wedding present.32 But there would be a fifth, unwritten source, perhaps the most eloquent of all: Nils Strindberg’s Zeiss photographs.

At first the launch mishaps seemed comparatively minor, almost comic. The crew had drunk champagne, and were in high spirits. One of Nils’s early almanac entries describes how he climbed into the hoop to admire the view, and the following cheery dialogue took place: ‘Look out, Fraenkel!’ ‘What’s up?’ ‘You’ll get a shower-bath!’ ‘All right!’33 Evidently Nils was happily urinating. The balloon found its new equilibrium at around a thousand feet, and stopped losing so much gas from its automatic valve. The wind was carrying them briskly north, though also several degrees eastwards. Still hoping eventually to adjust their course with the sails, Andrée had all hands splicing new full-length trail ropes from what remained of the originals. But he was relaxed enough to go below for an Arctic siesta.

All that first afternoon of 11 July the ballooning was smooth, sunlit and bucolic. They were thrilled by the sense of entering so swiftly and so easily into the unknown land of ice and snow. Nils recorded: ‘Only a faint breeze from South East and whistling in the [Giffard] valve. The sun is hot but a faint breath of air is felt now and then. Andrée is sleeping. Fraenkel and I converse in whispers … Ice is glimpsed a moment below us between the clouds. Course North 45 East magnetic. We are now travelling horizontally so finely that it’s a pity we are obliged to breathe (as that makes the balloon lighter of course).’34 It seemed almost magical.

It was only later, when he had time to make his calculations, that Andrée realised how much vital ballast they had lost. Adding together the eight hastily-emptied sacks of gravel (450 pounds) and the disconnected trail ropes (1,160 pounds), it amounted to rather more than 1,600 pounds, or one-third of their total ballast. As ballast equals flying time, this immediately shortened the balloon’s possible endurance in the air by as much as half.35

There was also the problem of why the balloon had descended into the water in the first place. Possibly it had not been ‘weighed off’ properly. Possibly its sails had caught an unlucky downdraft of wind across Virgo Bay. Or possibly the balloon was leaking, and simply lacked lift, exactly as Dr Ekholm had feared. If so, this would require some radical rethinking of the journey. While Andrée lay below in his bunk, pondering these problems, Fraenkel prepared food, and Nils began photographing. He also started keeping a plotted chart of their course.

‘Our journey has hitherto gone well,’ Andrée entered briskly in his first recovered message, dropped by buoy at around 10 p.m. on 11 July. ‘We are still flying at an altitude of 250 metres [830 feet] on a heading at first North 10 East, but later N. 45 East. We are now well in over the ice field, which is much broken up in all directions. Weather magnificent. In best of humours … Above the clouds since 7.45 p.m.’ It was signed as a team: ‘Andrée, Strindberg, Fraenkel’.36 Amazingly, there is no mention of the lost ballast ropes, or any comment on their increasingly eastward heading. Until midnight on 11 July the balloon continued to fly high and stable at around one thousand feet, but also continued to turn eastwards. In fact, by 1 a.m. on 12 July it was flying due east, no longer heading north at all. Nevertheless, up till then progress had been little short of astonishing. By the end of the first twelve hours they had covered some 244 miles, which was genuinely impressive. A sledge would have taken three weeks at best to cover the same ground.

At around 1.30 a.m. on 12 July, the loss of gas suddenly began to make itself felt. Entering a cloud, the balloon lost the warming influence of the sun and sank steadily into a new world: that of Arctic ground fog. From then on, conditions changed dramatically. Within four minutes the Eagle had dropped from eight hundred to sixty-five feet, and for the first time since Spitsbergen one of the shortened drag ropes touched the ice. The balloon would never again rise above three hundred feet.37

The crew did not know this, but their mood darkened. Nils noticed a huge, blood-red stain on the ice, where a polar bear had made a kill. It seemed ominous.38 They could now see that what appeared relatively smooth and benign from a thousand feet was actually a surface of fearful irregularity, with twenty-foot humps and gullies of ice, sharp edges and rugosities, where the ice pack had stacked and compacted under huge wind and submarine pressure.

At the new low altitude, the balloon slowed to almost walking pace; worse, it gradually turned completely around and started to drift westwards. They were virtually retracing their steps. Throughout the day they threw out more ballast, including, at 4.51 p.m., the biggest buoy, originally intended to mark the Pole itself, or at least their furthest point north. Significantly, it was thrown overboard ‘without communication’. This also suggests their change of mood. Immediately afterwards, the basket actually struck the ice forcibly, ‘several times in succession’.39 By 5.14 p.m. they had had ‘eight strikes in thirty minutes’. This was menacing.

Throughout the remainder of 12 July, the Eagle’s speed and prospects steadily deteriorated. They were no longer advancing towards the Pole at all. Another of Andrée’s key concepts, the ‘steady summer breeze towards the Pole’, had failed to materialise.

As they sank into the freezing fog, the sun disappeared altogether, and their horizon closed down claustrophobically, with visibility reduced to less than a mile in all directions. Their voices came back to them with a dull, muffled echo. It grew much colder. The ice no longer glinted and shimmered, its blue and white beauty replaced by a dreary, featureless grey. This gave Nils’s cameras nothing to focus on, producing photographs without depth or scale. ‘The snow on the ice a light dirty yellow across great expanses,’ noted Andrée. ‘The fur of the polar bear has the same colour.’40

Nils found himself waiting for the basket’s next strike, each one shaking the wickerwork and vibrating up through balloon’s entire rigging, making the canopy snap and creak overhead. He described this with an expressive term: ‘the balloon’s stampings’. It was as if the Eagle was putting its foot down, angrily demanding to kick clear of the hostile world of ice. Should they try to anchor, and wait for a better wind? Should they expend yet more precious ballast, and try to ascend above the fog? Uncertain what to do next, Andrée again went below to take stock and sleep on the single bunk. Nils and Fraenkel were left on watch.

At some point Nils climbed into the balloon hoop to be alone, and to write his letter to Anna. His thoughts went both into his almanac and into his letter, though with slightly different emphasis in each. In the letter he was determinedly cheerful: ‘12 July. Being up in the carrying ring is so splendid. One feels so safe and so at home. One knows that the bumps up here are felt less and this allows me to sit calmly and write to you without having to hold on … Andrée is lying [below] in the basket cabin asleep but I expect will not get any proper rest. The sun vanishes in the fog.’41

Nils’s later almanac entry gives an optimistic account of their progress during the earlier part of the day, when the sun still partially shone through the fog. But the misdating of the entry ‘12 June’, instead of July – suggests an element of distraction in his thoughts.

12 June 21 hours 5 minutes o’clock … This morning the height of car was 60 metres [190 feet] when the fog lightened enough to allow the sun to peep through. Every so often patches of blue sky. A refreshing sight after all the ‘stampings’ during the night. The carrying power of the balloon also increased finely. I wondered if we will make a high-level journey?

But by the time Nils wrote this entry, just after nine o’clock on the evening of 12 July, the chances of returning to a ‘high-level journey’ were slipping away. The balloon was growing heavier every hour with moisture from the freezing fog, and the lifting power of the remaining hydrogen was reducing as its temperature dropped: ‘Hard and continuous bumps against the ground resulting from the fog that weighs us down.’ Nils also noted that the wind direction had swung further round, ‘90 to 100 degrees’, and was now threatening to blow them almost due west. Finally, at about 10 p.m., they stopped moving altogether – one of the drag ropes had become caught beneath a block of ice. At least temporarily, they were completely stuck – ‘fastened very well’, as Nils pointedly put it. Perhaps initially it was something of a relief. But now their progress did not look so impressive. After twenty-two hours’ flying, they were supposed to be over halfway to the Pole, but they had not reached even 82 degrees North. They would remain stuck for the next thirteen hours.42

From these entries of 12 July, it is possible to conclude that Nils had begun to have doubts about Andrée’s balloon technique. He might have begun to wonder if the trail ropes and sails should be abandoned altogether. Perhaps they still had enough spare ballast to throw out, and let the Eagle fly freely into the Arctic sunlight? Once higher up, beyond one or even two thousand feet, the hydrogen would expand in the heat, the lift would rapidly increase, and the balloon would come to life again. By adjusting the Giffard valve, they could find a new ballast equilibrium and risk ‘a high-level journey’. They could finally take the glorious chance of a free flight across the Pole.

Andrée was up on deck within an hour of Nils’s almanac entry. He made a brief official report in his own journal, dated 12 July, 10.53 p.m.: ‘Everything is dripping and the balloon heavily weighted down.’ Then for about thirty minutes he obviously had a discussion about their prospects with Nils and Fraenkel. He noted what they all felt: ‘the balloon sways, twists, and rises and sinks incessantly. It wishes to be off, but cannot.’43 He then ordered them both down below to rest in the balloon car. They seem to have gone reluctantly. The question evidently discussed was whether they should cut the trail ropes, drop ballast and attempt a free flight above the fog before it was too late. The wind might take them west towards Greenland, or it might turn north towards the Pole again, or it might even carry them back southwards towards Spitsbergen. But at least it would be a flight. Though Andrée does not specifically say so, Nils – and probably Fraenkel – argued for this, ‘the higher journey’. It was perhaps the most momentous decision of their expedition.

Andrée wrote in his journal soon after the others had gone below:

11.45 p.m. [12 July] Although we could have thrown out ballast, and although the wind [now blowing due west] might perhaps carry us to Greenland, we determined to be content with standing still. We have been obliged to throw out very much ballast today, and have not had any sleep nor been allowed any rest from the repeated bumpings, and we could not have stood it much longer. All three of us must have rest, and I sent Strindberg and Fraenkel to bed at 11.20 o’clock, and I mean to let them sleep until 6 or 7 o’clock [on 13 July] if I can manage to keep watch until then.

There was no hint in this entry of any dissension. The determination to ‘stand still’ seems to have been mutually agreed between the three of them, as a team. Yet the feeling that they ‘could not have stood it much longer’ suggests a certain tension. Andrée also added a curious reflection: ‘If either of them should succumb it might be because I have tired them out.’44

Andrée was now alone on the deck of the stationary Eagle for several hours, until early in the morning of 13 July. It was a rare moment of solitary command, a historic pause: the heroic aeronaut aboard the greatest of the nineteenth-century free balloons. Using his Zeiss binoculars, he gazed around at the desolate, grey-yellow ice stretching to the horizon in every direction. The low fog and the utter solitude pressed down upon him: ‘Not a living thing has been seen all night, no bird, seal, walrus or bear.’45

The balloon swayed slightly at the end of its trapped trail rope. At some point he sat down on the little wooden barrel they used as a seat, opened his journal on his knee, and made his longest and his only personal entry during the entire expedition.

Is it not a little strange to be floating here above the Polar Sea? To be the first that have floated here in a balloon. How soon, I wonder, shall we have successors? Shall we be thought mad, or will our example be followed? I cannot deny but that all three of us are dominated by feelings of pride. We think we can well face death, having done what we have done. Is not the whole endeavour, perhaps, the expression of an extremely strong sense of individuality which cannot bear the thought of living and dying like a man in the ranks, forgotten by coming generations? Is this ambition? The rattling of the guide-lines in the snow, and the flapping of the sails, are the only sounds to be heard, except the creaking [of the wind] in the basket.46

As Andrée clearly intended, this is a historic statement in the development of ballooning. It poses the question: are they at the beginning, or at the end, of a great tradition of aerial exploration?* Yet the truly surprising feature of this entry is its philosophical resignation. There is no sense of planning ahead, of assessing their chances. Andrée, like his balloon, is stuck fast, psychologically immobilised.

There is no attempt to consider options, or practical alternatives. It is almost as if the whole expedition is already over – ‘We think we can well face death, having done what we have done.’ For Andrée, after little more than thirty hours, death is now the most likely outcome. Yet clearly these were not the feelings of either Nils or Fraenkel, who had every reason to live, and to return to Sweden.

By mid-morning on 13 July everyone had slept, and the situation had changed again. The capricious wind had come round through nearly 180 degrees, and was blowing eastwards once more. At 11 a.m. the trail rope, pulled in the reverse direction, suddenly broke free from the ice, knocking them all off their feet. They were now sailing back eastwards, on an almost reciprocal course. They resorted to a hot meal washed down with several bottles of ‘the King’s Special Ale’.47 Then Andrée released four pigeons bearing the same very brief message. He gave their latitude as 82 degrees 2 minutes North, and said they were making ‘good speed’ to the east. He added less than a dozen words: ‘All well on board. This is the third pigeon post. Andrée.’

Ominously, there were no further details of their plans or prospects; no personal comments; and no signature from either Fraenkel or Strindberg. Probably Andrée simply did not want to admit the true position.48 But it was clear. At 5 p.m. that day they crossed back over exactly the same point at which they had been twenty-five hours earlier, at 4 p.m. on 12 July. The balloon had simply performed a huge west–east dog’s leg. They had covered a further two hundred miles over the ice, but got not a mile nearer the Pole.

By this stage the technical state of the Eagle was critical. It was beginning to bump on the ice again, and it was now clear that the fog had frozen yet more moisture onto the balloon canopy and network cords, adding hundreds of pounds to her weight. The failure of the sun to emerge throughout 13 July meant that this process of icing-up was ever-accelerating. It was a situation, despite all his analysis of Arctic ‘data’, for which engineer Andrée had provided no ‘design solution’.

As the afternoon of 13 July wore on, the bumpings made things increasingly difficult in the basket, and it became colder still. Andrée seemed lost in thought, Fraenkel let the cooker catch fire, and Nils started to feel ill: ‘I tried to lie down in the car at 7 o’clock but in consequence of the bumping I became seasick and spewed.’ He went up alone into the ring, pulled on ‘a pair of balloon-cloth trousers, and an Iceland jersey’, and read Anna’s last letter. ‘It was a really enjoyable moment.’49

At 8 p.m. on 13 July, probably in response to Nils’s urgings to return to a ‘high-level journey’, Andrée ordered a major dump of ballast. They threw overboard six more marker buoys, the winch, the night-stool, and most of the remaining sacks of gravel. In total this amounted to 550 pounds, an enormous weight, which should have lifted them back well above the clouds. The Eagle stirred in response, rose to two hundred feet, and then stubbornly hung there, still shrouded in icy fog. By 10.30 p.m. it was down again, and striking violently against the ice.50

The only possible remedy was now so extreme that it would be a complete aeronautical gamble. Unless they threw out some of the equipment in the upper storage cone – which consisted of the tinned food, the spare ammunition, the sledges, the tent, the collapsible boat and the cooking fuel, all of it vital for survival down on the ice – the Eagle would never rise again. It was exactly the dilemma defined by Dr Ekholm. Did Andrée really trust the balloon alone to get them ‘safely out of the Polar area’, and back home? Would they commit themselves completely and finally to the air, rather than to the earth? They must have discussed this dilemma throughout the ‘night’ of 13 July, although there is no record in either Andrée’s or Strindberg’s journals of what may have been said.†

* They did have successors, but not as Andrée had imagined. In 1907 and 1909 an American journalist, Walter Wellman, attempted to fly an airship from Dane’s Island, but only got thirty miles out and crashed on a glacier. In 1923 and 1925, the great Norwegian Antarctic explorer Roald Amundsen made two attempts to fly over the Pole by twin-engined seaplane, one from Alaska and one from Spitsbergen, During the second expedition he successfully landed on the ice at 88 degrees north, thereby beating both Andrée’s and Nansen’s records, and successfully flew back three weeks later. But perhaps his most appropriate feat was to launch an airship, the Norge, from the site of Andrée’s launch on Dane’s Island in 1926, and overfly the Pole itself. However, the first successful free balloon, in deliberate emulation of Andrée, did not reach the Pole until 2000. It had much modern equipment aboard, and flew the ‘high-level journey’ up to fifteen thousand feet. It was piloted by the British explorer David Hempleman-Adams, and actually managed a brief landing on the ice at 89.9 north. But it did not quite fulfil Dr Ekholm’s original stipulation, and fly back again. Both balloon and pilot were brought back in a helicopter.

† The physical and psychological stress that Andrée and his crew faced are vividly illustrated by the balloon flight to the North Pole made by David Hempleman-Adams in 2000. He used the latest propane burners, an autopilot, a GPS satnav, the most up-to-date survival kit, an Iridium mobile phone, a radio link providing a constant stream of updated meteorological data, and a helicopter back-up team. Even so, it took him five days to reach the Pole, and he nearly didn’t make it. At one point he fell into exhausted sleep, hallucinated that he had landed, and awoke to find himself climbing out of the basket at thirteen thousand feet, believing the cloudbase to be solid, snow-covered ground. ‘Then I wake up. I am standing in the basket, with one leg thrown over the side … Only the harness is stopping me from jumping out, but I continue to jerk at the reins … then I realize I am floating several thousand feet above the polar pack ice, one tiny step away from plunging out of the basket … I feel frightened, really frightened, like no fear I’ve felt before.’ See David Hempleman-Adams, At the Mercy of the Winds (2001).