Of all the animals I’ve drawn, I find the lion to be the one that makes the most anatomical “sense.” The slope of the skull, the size of the shoulders, the paws, the overall skeleton, all the proportions—it just feels right. As I mentioned in the cat section, don’t make the mistake of thinking of lions (and tigers, for that matter) simply as large house cats. There really are a lot of differences. After all, no fireman has ever received a call to get a tiger out of a tree!

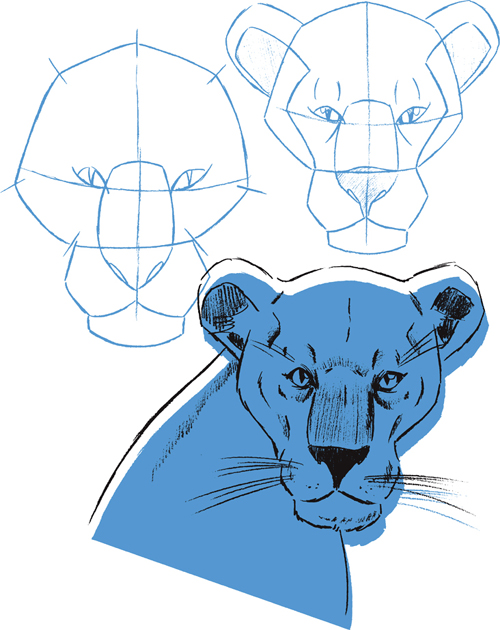

It’s better to start with a lioness, rather than a lion, because there’s no mane blocking our view of the head structure. And the major characteristics are the same for both lions and lionesses.

I’ve always been fond of drawing the lioness. Her construction is simple and unassuming, yet her look strikes fear in almost every animal she encounters. She is a contradiction of brute power and feminine slinkiness. She is the hunter of the pride. The male? A typical freeloader.

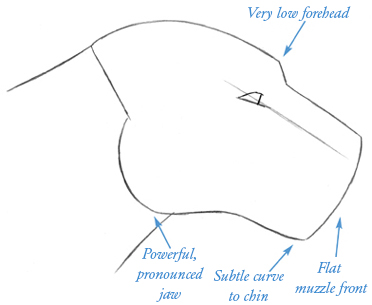

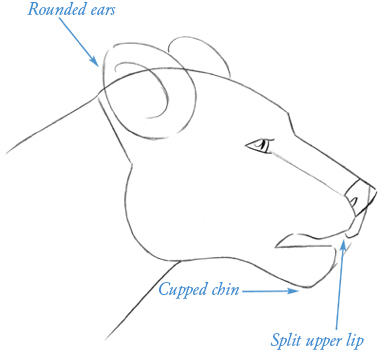

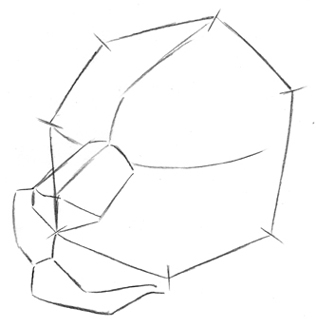

Unlike the house cat, the lion and lioness have longer muzzles, so it makes more sense to begin with the profile, rather than the front view.

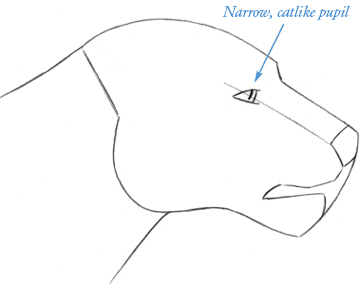

The most important things to keep in mind when constructing the lion and lioness’s head are that both have extremely low foreheads and large snouts that curve slightly downward.

As with many other animals with pronounced muzzles, the eye and nose fall on the same level. And as you did with the horse, “carve” a large masseter (or jaw muscle) into the lioness.

Add a shine to the pupil in order to give this big cat that piercing stare of a predator.

Note the facial contours, indicated by arrows here. In a relaxed pose, the lioness’s mouth hangs slightly open and reveals part of her fangs. The back of her mouth dips down. This isn’t an expression, but rather the way the mouth is formed.

Darken the eyelids, as if you were applying mascara. Emphasize the the tearducts and draw the eyelashes.

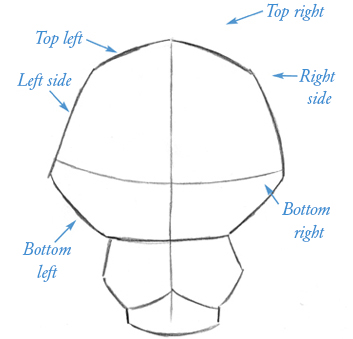

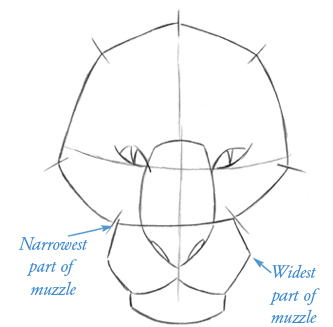

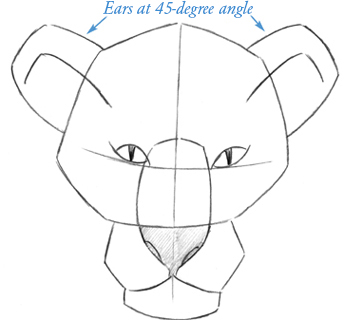

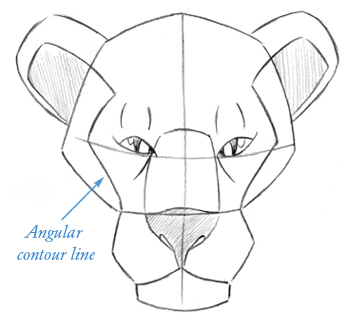

In the front view, the outline of the head is rounded but is not a true circle. And again, all the information here applies to lions, as well. (We’ll get to the lion’s mane.)

Note the angular shape of the head, with many planes. The muzzle elongates the face. The upper lip is puffed out and clearly split. The chin is squared off—more so than on any of the other animals in this book.

The bridge of the nose is wide, filling up the entire space between the eyes. Both the eyes and the nostrils tilt up at a 45-degree angle.

The pupils have thickness to them, but are drawn as slits. Make sure you always make the pupils bleed into the upper eyelids.

There is a distinct contour line that starts at the inner ears, continues to the cheekbones, and then into the muzzle.

The skull maintains its angularity in the 3/4 view. It has a rhythm to it: Thick, thin, thick. Thick skull, thinner bridge of nose, and thick muzzle.

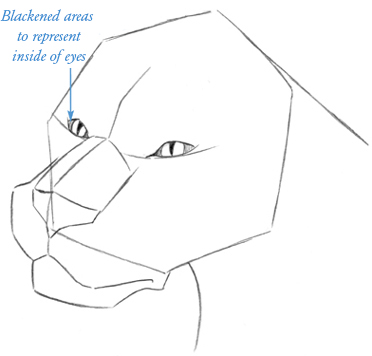

It’s important to sketch in the center line in the 3/4 view in order to maintain a balance on either side of the head.

Darken the inside the eyes except for the iris and pupils to represent the whites of the eyes. This will create the illusion of an intense stare.

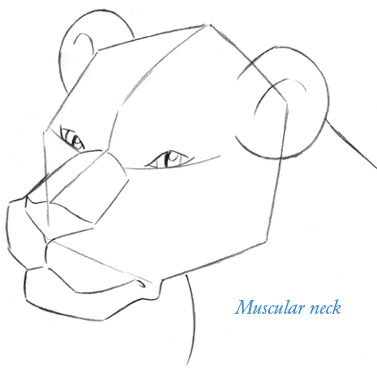

The neck widens into broad shoulders. The ears are placed at the top right and left of the skull.

Note that the face immediately gets wider above the bridge of the nose. And, the contour line that runs from the ear down to the muzzle evident in the front view is still visible in the 3/4 view.

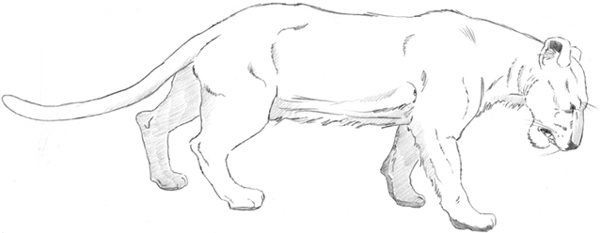

The lioness’s build is more fluid, with less definition between the body sections (the forequarters, midsection, and hindquarters). That’s not to say that these sections shouldn’t be defined; they should. But the skin is quite loose.

The shoulder blades are massive. The space between the rib cage and pelvic area is long, making room for a big belly so that the animal can eat large enough amounts of food to carry itself through lean days when food is not available. The rib cage and chest area is actually narrower near the upper chest and wider near the stomach. The tail is quite long and always hovers above the ground, if only by a few inches. (Compare to the tail position of the house cat on this page.)

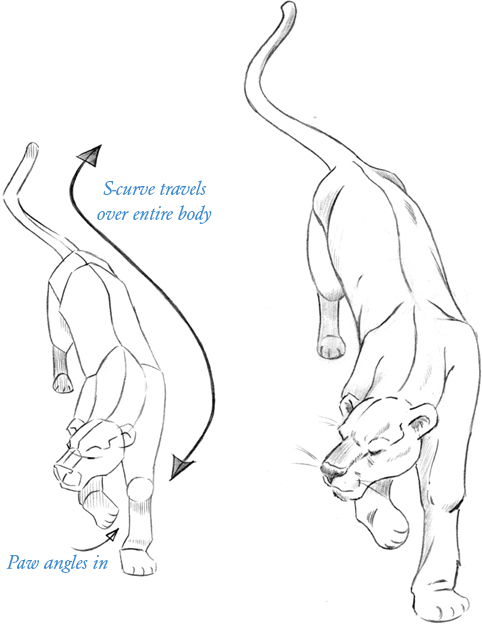

In addition, the overall body structure is rather horizontal, with a long torso carried low to the ground. The “arms” and “legs” are thick and somewhat stubby. The head is also often held low, with the nose pointed toward the ground, when the animal walks—a sign of a predator. A deer, for example, cannot afford to take its eyes off the horizon. One cannot help but get a sense of immense power when watching this animal in motion. Even a slow-moving lion or lioness exudes a feeling of primitive strength.

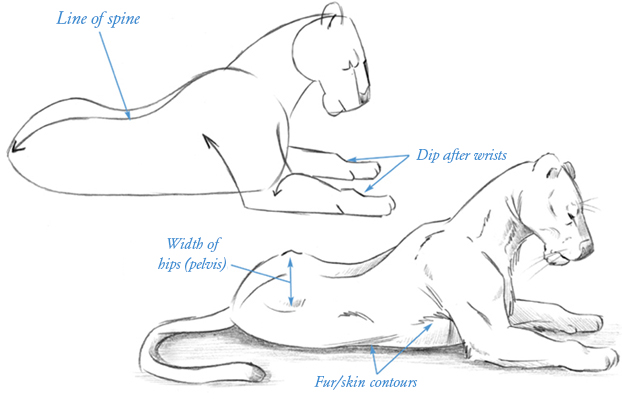

When the lion or lioness relaxes in a reclining posture, its hindquarters typically twist so that both legs are on the same side of the body. You can see the torso twist by following the line of the spine from the base of the neck down to the tail. Make sure that the shoulders are thicker than the hindquarters in this position.

Both the lion and lioness move gracefully, but they are also sturdy predators, moving slowly and keeping low to the ground—except when making lightning-quick strikes during an attack.

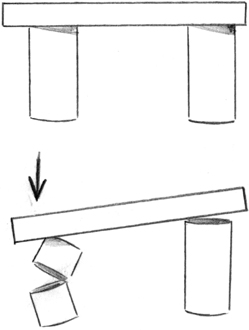

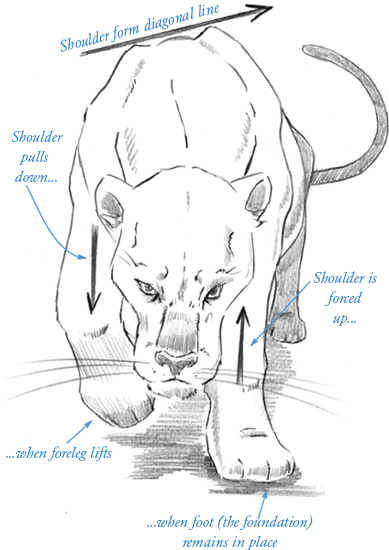

When one foreleg lifts off the ground, the shoulder on that same side has no support, so it sags. The shoulder on the other side, though, remains propped up by the other foreleg. As a result, the shoulder blades are at two different levels. (You should be able to draw a diagonal line across the two of them.) This is a dramatic look. But more important, it’s anatomically correct; conversely, it’s anatomically incorrect to draw the shoulders at the same level during the walk. The same principle applies to all four-legged mammals, but is pronounced on animals with large, muscular shoulder blades with good definition, which the lioness possesses.

When the support is removed, the slab slants downward.

From a high angle, or bird’s-eye view, most or all of the line of the spine is evident. Try to show the natural S-curve of the spine in the walk. Doing so will accentuate the slinkiness of the lion and create a fluid pose. In addition to being pleasing to the eye, it’s also anatomically accurate: When the lion walks, the shoulders tilt in one direction (to one side) while the hips tilt in the opposite direction (to the other side).

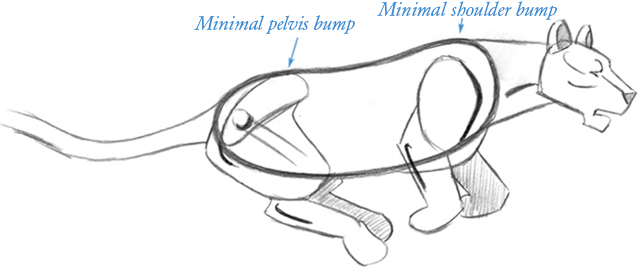

There is a point in the stride when all the legs are off the ground. Since no weight is on the paws in this moment, the shoulder blades and pelvis are not pushed up. As a result, they don’t make pronounced contours or bumps in the outline of the back as they would if the paws were on the ground. So, you can draw the body as a simple sausage shape, loose and relaxed. (The big cat is never tense, even on the hunt.)

The darkened lines on the neck, shoulder, legs, and hip highlight the contours that show through to the surface. The tail dips in the middle and then rises near the tip, like a delayed reaction, as the lioness runs.

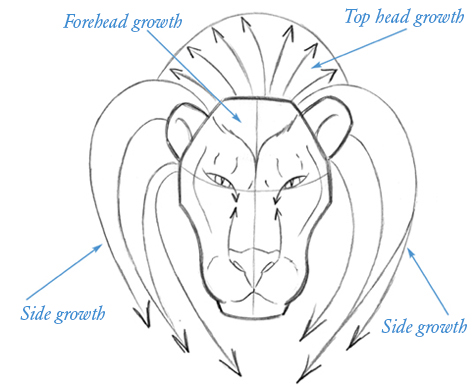

The male lion’s face is a little bigger that of the lioness. And then there’s the mane. The mane has three sections: the part on the forehead, the part over the back of the head, and the part that frames the face (this is the longest part).