RAILWAY RIVALRY

![]()

RAILWAY MANIA

The 1840s in Britain had been a decade of extraordinary expansion of the nation’s rail network. Speculators rushed to Parliament with their plans for railway construction (for the law required that each new line be the subject of its own special Parliamentary Bill), and engineers were kept busy providing plans for the promoters, many of whose schemes would never be put into practical effect. By the early years of the next decade, the broad outlines of the network were visibly in place. All the main cities of England were joined together by thin ribbons of iron, and the great days when fortunes were made from railway promotion were almost over. Yet ‘railway mania’ persisted, if at a less frantic level. Companies continued to be formed to join lesser towns to the main arterial lines by branches and spurs. There was little attempt by the promoters, and not much by Parliament, to develop these lines according to some well thought-out national strategy, and the combination of a lack of strategic planning and an excessive haste to realise elusive profits resulted in the development of lines which might never manage to pay their way. Inevitably these trends led to cut-throat competition between railway companies, and this in turn led either to the collapse of some companies, or to the merger of two or more companies together.

THE SCOTTISH RAILWAYS

In Scotland the situation was in some ways even worse than in England. The main Scottish companies, like their English counterparts the product of the glittering years of the mania, were mostly managed by men who had a real talent for promoting their lines and getting them built, but rather less for the day to day running of a rail system. ‘There is something wrong about the management of Scottish railways,’ commented a railway journal of the day, ‘notwithstanding the national character of that country for economy. But [in railway business] we find them to be comparatively extravagant in large matters, penurious in little, lax, and unsuccessful’.30 Amongst the particular weaknesses of Scottish railway management was failure to estimate accurately the costs involved in setting up a railway in the first place. In 1852 the Railway Times, writing about the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee line, complained that ‘experience has shown that no railway contract is ever completed for the price for which it is undertaken . . . The eagerness to embark in railways, as well as the inexperience of the difficulties and uncertainties attendant on them, appear to have alike deceived projectors, engineers and subscribers’.31 Thus the Caledonian Railway, which had allowed £173.000 for the purchase of land on which to build the line, ended up by paying nearly £390,000, while the North British, the Aberdeen, and the Edinburgh and Northern all paid out three times their original estimates. Huge sums also were expended on the Parliamentary and legal costs connected with getting the necessary legislation through, without which no work on building the line could even begin.

When it came to the actual operation of the lines, a series of enquiries into the Scottish companies revealed extraordinary stories of extravagance and financial irresponsibility – themselves born of the ruinous competition for routes between the major players in the business. On the one hand, companies committed themselves to guarantees to the shareholders of lines which they had leased, largely to prevent their rivals getting control of what they regarded as their territory, while on the other (and for the same reasons) they engaged in disastrous price-cutting exercises, making it impossible for those guarantees to be honoured. In the second half of 1850 four of the leading Scottish rail companies, the Caledonian, the North British, the Scottish Central, and the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee, all failed to pay a dividend to their shareholders.32

The 1850s and 1860s in Scotland saw an increasingly bitter battle being fought out between the major companies for a position of dominance in the railway business, and as time went on that battle developed into a contest principally between two giants – the Caledonian and the North British. The North British Railway Company had originated in 1846 as a relatively small concern, operating the line southward from Edinburgh to Berwick-upon-Tweed, but from these small beginnings had developed a growing empire of branch lines between the capital and the borders. In August 1862, under the control of expansionist chairman Richard Hodgson, the company took two important steps towards the major league – it inaugurated the new Waverley route from Edinburgh to Carlisle, and on the very same day took over the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee line, giving it control over the whole of the east coast route from Berwick to Dundee. More than that – the takeover of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee line would enable the North British to outflank the Caledonian, and develop an east coast network, at the heart of which was a line from Edinburgh to Dundee some 28 miles shorter than the Caledonian route.33

Over much the same time-span, the Caledonian had also been advancing on Dundee, but from the starting point of Carlisle, moving northward until it met with the southern end of the Scottish Central at Greenhill. In 1863 the Scottish Central took over the Dundee, Perth and Aberdeen Railway Junction Company, thus gaining direct access to Dundee, while from Dundee northward, the Scottish North Eastern Railway took the line as far as Aberdeen. As the Caledonian had negotiated an arrangement with both the Scottish Central and the Scottish North Eastern to have use of their lines, by 1863 the Caledonian effectively controlled the whole central route from Carlisle to Aberdeen, and within a further three years had consolidated its position by taking over both of the smaller lines. Thus, by the mid-sixties the Caledonian and the North British stood face to face across the Tay, ready for the final battle for supremacy. Which of them would emerge the victor would depend crucially on the building of the bridge over the Tay.34

There was of course a serious snag, or rather two – the two great firths of Forth and Tay, which separated the Kingdom of Fife from Lothian to the south and Angus to the North. So long as these huge natural obstacles remained unbridged, the advantage to the North British of having the shorter route remained academic. The dream of overcoming these obstacles had long been the great ambition of one of the central figures in the Tay Bridge tragedy – the engineer Thomas Bouch.

THOMAS BOUCH

Thomas Bouch was the third son of William Bouch, a retired captain in the merchant navy, and was born in the small village of Thursby in Cumberland in 1822. His interest in engineering as a career was first aroused, we are told, by a lecture on hydraulics given by the village schoolmaster, Joseph Hannah, and when Hannah moved to the headship of a school in Carlisle, young Thomas went with him to complete his education. After a brief and unsatisfactory period of employment in an engineering works in Liverpool, Bouch returned to Carlisle, where he was taken on by a local civil engineer called Larmer, who was currently engaged on the Lancaster and Carlisle railway. Bouch stayed with Larmer for about four years, went for a short time to Leeds, and then spent a further four years as resident engineer with the Stockton and Darlington railway. In 1849 he moved again, this time to become both manager and engineer of what was then the Edinburgh and Northern Railway, later known as the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee, a line which, as we have seen, was ultimately absorbed by the North British in 1862.35

THE ‘FLOATING RAILWAY’

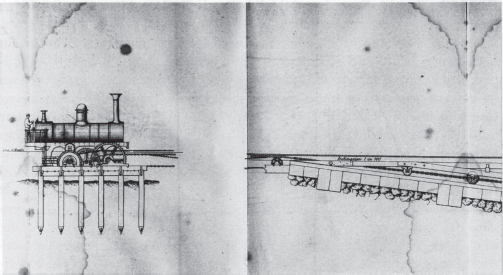

It was during his time at the Edinburgh and Northern that Bouch first confronted the problem caused by the wide estuaries of the Forth and Tay rivers. His solution to it was both ingenious and effective – not the construction of a bridge, which would have been quite beyond the means of the Company at that time, but the provision of what became known as a ‘floating railway’ – in fact a specially designed ferry boat with rails on the deck, on to which goods wagons were manoeuvred by means of a movable ramp on the quay. The vessel was designed by Thomas Grainger, the engineer who had built the line in the first place, while Bouch himself designed the ramp mechanism.36

One of the many obituaries of Bouch published on his death in 1880 gives full details of this simple but ingenious device:

The invention embraced three principal features – the inclined plane, the flying bridge connecting the moveable framework with the ship’s deck, and the means adopted to secure free space for the shipment of trucks on board. Upon a massive inclined plane of masonry, the moveable framework runs on sixteen wheels, the upper part of the frame presenting two lines of rails on the level, while below the beams and fillings take on the form of a slope. This framework is pulled up or down on the ship to suit the state of the tide. At its centre rise two uprights, with a crossbeam, the uprights sustaining heavy weights with chains over pulleys, and thence to strong cranes or jibs which, hinged at the outer end of the framework, support girders that stretch forward to meet the vessel. These hinged girders allow for the play of the vessel and for the rise and fall of the tide while loading and unloading go on. On board the vessel the difficulty arose that, as paddle wheels must be used to give breadth and stability for the rough crossing, the shaft would interfere with the clear run fore and aft. This difficulty was overcome by providing for each paddle a separate engine, with the result that on the several lines of rails trucks can be at once run on board over the whole deck space. The first cargo carried across the Forth by the vessel consisted of four hundred tons of turnips.37

There were of course already ferries in operation across both rivers when Bouch joined the Edinburgh and Northern, but the service they provided was slow, unreliable and expensive. On each river the company operated two boats for freight and one for passengers, but goods brought to the ferry terminal had first to be unloaded from wagons to boat and then loaded on to wagons again at the other side – a process which had to be repeated at the next crossing. Not only was this time-consuming, but the cost per mile to operate the ferries was a massive six times the operating cost of rail. Moreover the inefficiency of the system denied to the line the lucrative business of transporting very large loads. The great advantage of the floating railway was that it cut out the loading and unloading process – goods wagons were run directly on and off the boat.

Bouch was successful in persuading the company to go ahead with his scheme, and an order was placed for the first of the ferries – the Leviathan – with Napiers of Glasgow. The new boat was delivered to Granton in September 1849. On the 11th of that month Bouch wrote to the chairman:

The large steamer for conveying animals and merchandise across the [Tay] ferry was thought better adapted for the Forth, and has accordingly been sent there. A similar one in its stead is being built to effect the same object by Mr Napier of Glasgow and will be ready and on the passage by January next. By that time the necessary apparatus for running the wagons on and off board will be finished so as to enable you to send your goods and minerals into Dundee and Arbroath without change of truck.38

In fact it took longer than Bouch had planned to install the machinery, and Leviathan did not begin her work of transporting freight across the Forth until March of the following year. In operation Leviathan could carry up to 34 goods wagons, while the average time for a crossing, including loading and unloading, was just under an hour. Her counterpart on the Tay, the Robert Napier, was introduced in 1851, where with her sister ship the Carrier she ran from Tayport to Broughty Ferry until the opening of the bridge in 1878, and again from the fall of the bridge until the new bridge was completed in 1887. In March 1851 Bouch was able to report with some satisfaction on the ‘complete success of the floating railway used in the ferry. The steamer and apparatus have been at work thirteen months without so much as one single working day having passed without the conveyance of trucks safely across the firth.’ More than 29,000 wagons had been carried over the Forth by the rail ferry in the first six months of operation.39

THE BELAH VIADUCT

Shortly after this, and with his reputation in the profession firmly established, Bouch left the Company to set up as an independent consultant, and embarked on a long and successful career as the designer chiefly of cheap rail lines for small companies in the north of England and south-east Scotland. In this capacity he built some 300 miles of railway, though his most extensive single project, for the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway, was only 50 miles long, and the average length of his lines was only about 15 miles. He also built a number of viaducts to carry his lines across the rough country of the north of England. These included the Hownes Gill Viaduct spanning a deep ravine on the Darlington and Blackhill line, 700 feet long and 175 feet high at its highest point, the Redheugh Viaduct at Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and the Deepdale Viaduct carrying the Barnard Castle and Kirkby Stephen line over Deepdale Beck.40

Of his viaducts the best known and certainly the largest was Belah Viaduct, built for the North Eastern Railway over the little Belah river, to enable a line to be carried westward from Barnard Castle over the Pennines into Cumberland and Westmorland. Bouch’s plan called for the construction of a viaduct 1,010 feet long, carrying a double track, and with piers ranging from 60 to 100 feet in height, supporting 16 spans of 60 feet each. Two features of this viaduct (still standing more than one hundred years later, when it fell victim not to physical decay, but to Dr Beeching’s axe) connect it directly with the later ill-fated bridge over the Tay. In the first place the designs of the two bridges were similar, in that both of them made use of piers made up of hollow cast-iron columns braced together, these piers supporting latticework girders – a mode of construction which was simple, cheap, and offered only slight resistance to the wind at high elevations. In the case of the Belah Viaduct, Bouch’s employers had instructed him to draw up plans for both cast-iron and stone piers, but soon found that the cast-iron alternative would cost very much less both in time and materials. Secondly, the construction work was carried out by the Middlesbrough firm of Gilkes, Wilson and Co., who as Hopkins, Gilkes and Co., were also the principal contractors for the Tay Bridge. This collaboration was extremely successful – the viaduct was completed in only four months, using an ingenious technique which did away with the need for expensive scaffolding. The total cost of the project was only £31,630, and it was completed without a single injury or accident at any stage – an almost unique record.41 Moreover the Board of Trade inspector found the whole construction perfectly safe at the first inspection. The contractors’ achievement was commemorated in the following verse:

To future ages these lines will tell

Who built this structure o’er the dell,

Gilkes Wilson with his eighty men

Raised Belah viaduct o’er the glen42

THE ST ANDREWS LINE43

Bouch also became increasingly involved in railway construction in Scotland. The new managers of Scotland’s railways, who in many cases had supplanted the old guard by the mid-1850s, had come to the conclusion that the answer to the low earning potential of railways in thinly populated areas of the country was to cut down on construction costs. New lines could only be built economically where the local landowners were prepared to co-operate and make land available cheaply, where there was no opposition which could make the passage of the proposal through Parliament impossibly expensive, and where there was no need to build to the high specifications of the main line routes. One of the pioneers in Scotland of the movement to build cheap and unassuming lines was the St Andrews Railway Company, which employed Thomas Bouch as its engineer.

The St Andrews Company was well placed to carry out its objective of linking the town with the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee line at Leuchars. The land in between was flat, no large earthworks were required, and only two small bridges would have to be built. Most of the landowners over whose land the projected line would pass had a financial interest in the scheme, and the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee itself was happy to co-operate. In no position to build the line with its own financial resources, the company came to an agreement with the promoters to operate and maintain the line for twenty-five years after its opening. They also supplied the St Andrews Company with Bouch as the engineer, who submitted his estimates in August 1850, while still employed by the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee as manager and resident engineer. Although he resigned in the spring of 1851 to become an independent consultant, he retained the St Andrews Company as his clients, and designed the line for them for a fee of £100 per mile which, so he claimed, was about one fifth of the average engineering fees in Scotland at the time. He also took special care to reduce the cost of actual construction by ‘every economy consistent with obtaining actual safety’. This included specifying lightweight rails, and sleepers spaced four feet apart instead of the usual three. ‘With this slight road,’ he wrote, ‘it was arranged that light engines only should be used, and run at moderate speed.’44

It was with the St Andrews commission, then, that Bouch first established himself as a specialist in the construction of cheap, light railway lines, catering to the needs of companies with more enthusiasm than cash. His reputation ‘for contriving economical works’ carried him to other similar projects in Scotland and in England – the Leven, the Peebles, the Leslie, Crieff Junction, the Eden Valley, the viaducts already mentioned – and altogether he had completed some eighteen or nineteen rail constructions before embarking on what was to be the crowning achievement of his career – the conquest of the firths of Forth and Tay.

THE PLAN FOR A TAY BRIDGE

The idea of constructing an iron bridge across the Tay was not new. As early as 1818 a gentleman of Dundee had expressed a wish that someone might construct a bridge which would join Magdalen Yard Point to Woodhaven, ‘which would secure a safe easy and expeditious passage to and from y opposite county, without let or hindrance fr. either squally weather or sandbanks’.45 From time to time thereafter the idea was mooted, but with no practical result. Bouch himself had first put forward his plan for a bridge over the Tay in 1854, when still in the employ of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee company, only for the proposal to be rejected and himself ‘looked upon as a dreamer, and treated with an incredulity which was strangely inconsistent with the character of an astute businessman, whose knowledge of what engineers had already accomplished ought to have given them some conception of what man may command in his conflict with Nature.’46 For the next decade the bridge plan lay dormant, but the acquisition of the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Company by the North British in 1862 reopened the whole question of bridging both Forth and Tay, and chairman Richard Hodgson decided to give his backing to the scheme.

Initially the North British plan focussed on the Forth, and Bouch was commissioned to produce a plan for a Forth Bridge which would span the river between Blackness Point on the south side and Charleston in Fife. He designed a huge construction which, if built, would have been three miles long and 150 feet high, and although of course it never was built, some experimental work was done in preparation for it. In 1864 a huge iron cylinder was fabricated in Burntisland, taken out to the site of the proposed bridge, and sunk into the river bed. Once in position it was weighted down with large quantities of iron and measurements taken to see how far it sank. Curiously, Bouch himself was not present to observe the experiment, which in any case was eventually abandoned, and the cylinder sold for scrap.47

Developments with respect to the Tay Bridge, however, were more promising, and this was due in large part to local interest in the bridge project, at least among a small group of active and influential members of the business community in Dundee. In October 1863 a meeting to discuss the bridge project was held in the offices of prominent Dundee solicitors Pattullo and Thornton, and although nothing came out of that meeting directly, the Dundee Advertiser was quick to register its support of the scheme. A year later, Thomas Thornton, who was to take a leading part in the promotion of the bridge project, arranged for Bouch to explain his proposals to a public meeting in the Town Council Chambers, at which he unveiled plans for a bridge between Newport and Craig Pier (the site today of Discovery Point). There were to be 63 spans, and at its highest point the bridge would tower 100 feet above high water. On the Dundee shore, the rails would curve round to the west rather than the east, and join up to the line to Perth at Magdalen Green. The audience on this occasion was largely made up of businessmen and textile industrialists, who could readily grasp the advantages of having direct and speedy access to the coalfields of Fife to fuel the steam engines driving the machinery in their mills. If there were doubters among them, daunted by the sheer scale of the project, Bouch was ready to reassure them. ‘It is a very ordinary Undertaking,’ he is reported to have said, ‘and we have several far more stupendous and greater bridges already constructed.’ Encouraged by Bouch’s confidence, the great advantages of a direct rail link with Fife, and the prospect of good returns on the investment, the meeting resolved ‘that it would be for the public advantage, and tend greatly to the traffic of the North of Scotland and specially the town and trade of Dundee, were the present inconvenient and expensive route to the south improved by the construction of a bridge over the River Tay.’ A committee was appointed to promote the scheme, and on 4 November 1864 the prospectus of the projected Tay Bridge and Union Railway was issued, based on the capitalisation of £350,000, divided into 14,000 shares of £25 each. By mid-November plans were sufficiently far advanced that notice was given of a Parliamentary Bill to provide for the incorporation of the company, and for the construction of the bridge and connecting lines.48

If the promoters of the Undertaking had expected an easy passage for their bill through Parliament, they were soon to be disillusioned. While the project might be warmly welcomed by some interests, it was as warmly opposed by others, and opposition to the bill soon began to gather momentum. Naturally enough the principal opponent of the scheme was the North British Railway’s great rival, the Caledonian Railway, not to mention the smaller Scottish Central and Scottish North Eastern Railways, who had no wish to see the North British extend its lines north of the Tay. In Dundee itself a powerful negative voice was that of the Harbour Board, largely composed of members of the Town Council, and jealous of the interest of the port as the principal gateway into the city for the passage of goods. Twenty miles upriver lay the city of Perth, ancient rival of Dundee, and anxious that its already diminished role as a port should not be destroyed altogether by the barrier of a bridge across its path to the open sea. In actual fact, the failure to dredge the river adequately upstream from Newburgh meant that Perth was already inaccessible to ships with masts as high as 100 feet.49 In the end Perth Town Council was simply bought off, being promised the sum of £500 as soon as work started, plus an annual payment of £25 for every foot under the original 100 feet of clearance below the high girders. The distance was eventually set at 88 feet.50

This arrangement was, however, well into the future. In the meantime, in an attempt to meet some of these objections, significant changes were introduced into the plans, and these were explained in great detail to the readers of the Advertiser in December 1864. The site of the bridge was now to be one mile west of Newport Pier, and as it would now cross the river at a wider point than before it would be longer and include more spans – 80 instead of 63. The longest of these, over the deep water channel, was to stretch the enormous distance of 300 feet, at a height of 100 feet above the high water mark of the spring tides.51 This was only one of many different versions of the bridge plan to be made, but it was never put to the test. Lobbying against the bridge bill by the Caledonian began to tell, support for the Undertaking began to crumble, and the promotors decided on a tactical withdrawal. The bill fell through.

In 1866 a second bill was promoted. The new scheme was significantly different from the original plan in a number of ways. On the south side, the line was to be connected not only with Tayport, but also with Leuchars, and the bridge was to cross the Tay from Wormit Bay to a point west of the Binns of Blackness. From there the rails were to be carried over the Dundee to Perth line, and then eastwards towards the centre of town by way of the gardens of the houses of Magdalen Yard Road, the Perth Road and the Nethergate, until they arrived at a magnificent new Central Station in the middle of the city.52

In connection with this scheme, the North British also became involved with the Town Council in a plan to develop the area to the south of the Caledonian railway line as it entered Dundee. In its 1866 bill, the railway conceded the rights of town to this area, and after the Council had successfully promoted a bill to construct the esplanade along the foreshore, the North British and the Caledonian put up £13,000 for making up the ground inland of the esplanade for railway purposes. A similar sum was contributed by the Harbour Trust towards the cost of the esplanade itself.53

This agreement seems to have been instrumental in overcoming the Council’s opposition to the bridge proposal, and at the same time something of a truce had been reached with the Caledonian, both companies being unwilling to waste still more money on expensive legal battles. For its part, the North British withdrew its bid for the Scottish North Eastern, which both companies had had an interest in acquiring, and in return the Caledonian withdrew its opposition to the bridge, and even agreed to allow the North British use of its lines from Dundee to Aberdeen once the bridge was completed. No further obstacle now seemed to stand in the way of the project, but unfortunately at this crucial moment the North British was crippled by a severe financial crisis, brought on by overspending and weak financial management. Chairman Richard Hodgson, the great champion within the company of the bridge project, was forced out, and the second bill was withdrawn.54

JOHN STIRLING OF KIPPENDAVIE

The new chairman of the North British Railway Company was John Stirling of Kippendavie, a landowner and successful businessman, with many years’ experience of the railway business in Scotland. Until its recent takeover by the Caledonian, he had been chairman of the Scottish North Eastern Railway. Far-sighted enough to grasp the importance of the bridge for the Company and for the east of Scotland, Stirling roused his fellow directors on the North British board in support of the bridge, and the fight was on once more. A new and less ambitious bridge scheme was adopted, involving a crossing from Wormit to Buckingham Point, curving round to the east along the line of the foreshore into a new station which was to be built on the made-up land to the north of the esplanade. From there the rails would be carried by way of a tunnel under Dock Street to join up with the line to Arbroath.

On 5 September 1869 a deputation from the North British, consisting of Stirling, Bouch and James Cox, met with members of the Town Council and the Harbour Trust. Stirling played his cards well, appealing both to the civic pride and the financial self-interest of his audience. The proposed bridge, he assured them, would be of great benefit to the coal trade of Fife, and the trade and shipping of Dundee. It would place the city directly on the main route to the north, instead of being relegated, as now, to a mere siding. With the bridge to link Dundee with the southern shore of the Tay, the journey to Edinburgh would take only an hour and a half, and only half an hour to St Andrews. The total cost, including bridge, approaches, and a tunnel to take the line eastwards under Dock Street, would not exceed £350,000, and it was the intention of the directors to guarantee a return of 5¼% to stockholders. This return, as the directors were to explain to an extraordinary meeting of the North British shareholders in November, would easily be met from the savings which would arise from doing away with the ferry across the river, and from no longer having to pay £9,000 a year to the Caledonian for the use of the Broughty Ferry to Dundee rail link. In a scheme such as this there could be no losers.

In November a public meeting was called in Dundee to promote the Tay Bridge Undertaking, a meeting which ‘largely represented both the solid judgment and the youthful vigour which have enabled Dundee to take its present position as one of the most enterprising commercial towns in the kingdom.’ Once again John Stirling was at his most persuasive, explaining to the assembled businessmen that of all the advantages which the bridge would bring, ‘The greatest advantage of all, undoubtedly, will be the shortening of the distance between the pit mouths of Fife, and the furnaces and ship’s hatchways in Dundee.’ Mr Stirling, we are told, ‘put this most moderately, but all businessmen instinctively appreciate it.’ They no doubt also appreciated being told by Stirling that if it should happen that the bridge cost more than the estimated £350,000, then the same guarantee of 5¼% return would extend to the additional capital required to complete the project.55 The Undertaking was launched, the subscription list was opened, and the first name on it was James Cox, chairman of the Undertaking and a director of the North British, who put himself down for 200 shares. On 15 July, 1870, the Parliamentary Bill for the Tay Bridge received the Royal Assent.56

THE SEER OF GOURDIE

Not everyone shared the general enthusiasm for the bridge. Prominent amongst its opponents as Parliament moved closer towards approving the scheme was farmer Patrick Matthew – the ‘Seer of Gourdie’ – who uttered Cassandra-like prophecies of doom in a series of eight letters to the Advertiser between December 1869 and March 1870. In these letters Matthew foresaw all sorts of mishaps which might befall the bridge – scouring of the foundations by the rapid flow of the river beneath; collapse of bridge supports through collision with a ship; loss of the train by centrifugal force as it took the sharp curve at the north end of the bridge; destruction of the bridge by tremors of an earthquake.57

The Advertiser, committed to the scheme, was quick to dismiss Matthew’s fancies.58 But despite his own description of himself as a ‘crotchety old man with a head stuffed with old world notions, quite obsolete in the present age of progress’, Matthew was very far from being a mere crank. His advice that the bridge ought to be strengthened at the north end where it curved sharply east towards Dundee preceded an announcement that just such additional piers and columns as he had suggested would be provided, and his arguments in favour of an alternative and much cheaper bridge at Newburgh were never publicly answered. Matthew’s vision was of a city where the money saved by not building the Wormit bridge would be used to clean up the slums and build healthy good-quality housing for the working class, and his views on town planning were at least half a century in advance of their time. To the readers of the Dundee Advertiser he declared roundly, that ‘I would only put the rainbow bridge, with its disposition to destruction, into the one scale, and the sanitary improvement of the impure heart of the city, alongside the superior bridge at Newburgh in the other scale; which’, he asked, ‘would kick the beam?’

Matthew had been particularly concerned that the bridge might be brought down perhaps by an earth tremor – the ‘sleeping giant . . . whose strugglings are felt every season’. This, he thought, would be ‘quite sufficient to capsize the Wormit bridge which, being so high and heavy – so crank, like a narrow boat with tall people standing in it – would be easily upset.’ Few people took any notice. But before he died in September 1870, Matthew issued one final macabre warning. ‘In the case of accident with a heavy passenger train,’ he prophesied with fearful accuracy, ‘the whole of the passengers will be killed. The eels will come to gloat over in delight the horrible wreck and banquet.’59