AFTER THE FALL

![]()

FIRST REACTIONS

Madam,

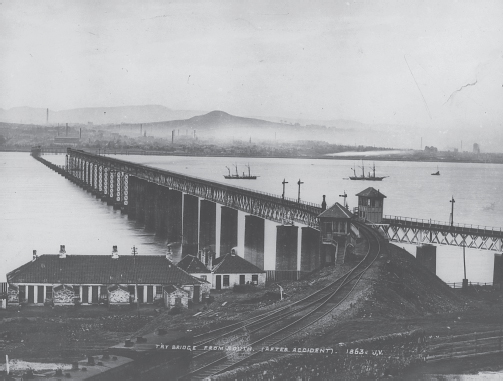

Last night will be remembered in the history of Fife for all generations to come. None living in the North of Fife has yet seen or felt such a night the Great Tay Bridge is fallen, and the 7 o’clock train from Edinburgh is also down with it and all the passengers lost. And it is now very painful for me to say that David Cunningham is lost. By the deplorable Fall of the Taybridge he and a young lad from the Gauldry Ann Dewar Son Ann will know him they took the train from St Fort station to go to there work to the new Asylum near Lochee. I went to see the broken down bridge to find out about the trains knowing that David C was to cross. What a sight it is now the 12 large High Pillars with the High Girders is all down with all there Iron Works is now out of sight in the water . . . to know and think that your Neighbours and Acquaintances is laying in the cold Tay is very trying to flesh and blood.97

So wrote Angus Mackay in his distress to Miss Morison Duncan on Monday 29 December 1879. How many such letters must have been sent to bring the tragic news to households near and far. And of course for those with no personal line of communication, the local and national press were quick to publish what news there was, and send their newsmen and graphic artists in all haste to the scene to discover more. First accounts were inevitably brief. The correspondent in Monday’s Times reported simply that:

Tonight a heavy gale swept over Dundee and a portion of the Tay Bridge was blown down while the train from Edinburgh was passing. It is believed that the train is in the water, but the gale is still so strong that a steamboat has not yet been able to reach the bridge. The scene at the Tay Bridge station is appalling. Many thousand persons are congregated around the buildings, and strong men and women are wringing their hands in despair.98

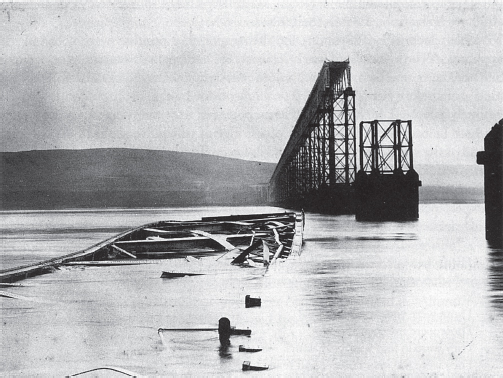

By the time this report appeared on the breakfast tables of the nation, the scene on the Tay was clear to watchers on the shore. The weather was now calm, and the surface of the river displayed no trace of the turbulence of the night before, but what it did show was the terrible gap where the High Girders had once stood. But what had happened to the train and its passengers? To a telegram from the Queen’s private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, expressing the royal dismay and asking for more information, the Provost could only pass on the erroneous information provided by the railway officials that nearly 300 passengers, as well as the servants of the company, were believed to have died. As to the causes of the disaster, Sir James Falshaw, deputy chairman of the North British, was quick to explain it as an act of God, and therefore the fault of no man. Few were inclined to agree with him, and the President of the Board of Trade announced the setting up of a Court of Inquiry that very day. By the time the newspapers had got over the initial shock of the tragedy, their approach to the question of blame was remarkably philosophical, and to the question of the rebuilding of the bridge remarkably positive. While recognising the central role and responsibility of Sir Thomas Bouch, few were prepared, at this stage at least, to cast him in the role of scapegoat. As the Glasgow Evening Times reflected,

Sir Thomas Bouch had necessarily to use his own judgement in regard to points of novelty on which the experience of other engineers would give him but small assistance. His work, taking into account its surprising cheapness, had been universally pronounced a success, and there can be little doubt that it would in ordinary circumstances have become the parent of many similar structures. Encouraged by the Tay Bridge the engineers would have boldly essayed to answer the call of enterprising capitalists by offering to throw arches over any estuary, however wide. But it is inevitable that this accident should produce circumspection and caution.99

Closer to home, the Dundee Courier was even more bullish about the whole scheme, confident that the bridge would have to be rebuilt without delay (as indeed the senior officials of the North British had already privately decided) and anxious only that this time the bridge should carry a double track, since in addition to the operational advantages, ‘it is clear that if we are to have an erection on which the public will venture their lives, it must be one of a broader base, of less height, and one less top heavy than that which was wrecked on Sunday evening.’100

THE SEARCH BEGINS

The rebuilding of the bridge would not even be begun for some years, and there were many more pressing matters to attend to first. Chief among them was to carry out a search for the remains of the victims, and a thorough investigation of the remains of the bridge and the train.101

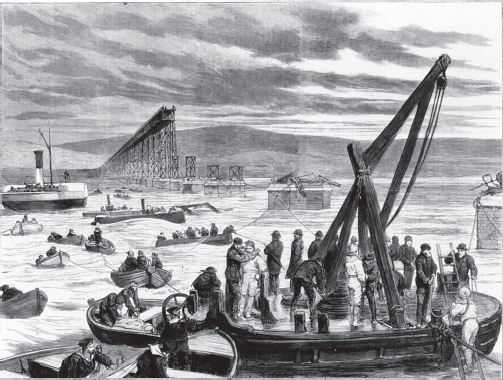

The search began at first light on the morning of the 29th, when the steam launch Fairweather made its way upstream to the bridge with harbourmaster Robertson on board, together with John Fox, a diver employed by the Harbour Trust. Fox was sent down at a point about thirty feet to the south of the third pier of the high girders, and from that point on the river bed he was able to see along the fallen girders in both directions until they were lost in the murk. There was no sign of the train.

When it became clear that for the time being the divers could do no more, the Fairweather was steamed along the line of the bridge, and an examination carried out of the piers which had supported the high girders. They were a sorry sight, with the iron columns snapped off and lying in a tangle on the broken stonework of the piers, though the brickwork of the piers in all cases was practically undamaged.

Shortly after eleven o’clock that same morning a second steamer, the Forfarshire, left the harbour to join in the search. On board it carried the Provost, James Cox, Dugald Drummond, and the brooding figure of Sir Thomas Bouch, as well as a number of officials of the North British Company. For some hours it passed backwards and forwards along the line of the bridge, but found nothing.

At Taybridge Station orders had been given to prepare one of the refreshment rooms as a temporary mortuary. Outside the station, friends, relatives and bystanders waited in the gathering gloom for news, only to be told that there was no news, and that no bodies had yet been recovered. But in fact one had been. Late that evening, in shallow water further down the Fife coast, the body of a middle aged woman dressed in black was recovered by a mussel dredger, and conveyed to Dundee.102 It was the body of Anne Cruickshank, Lady Baxter’s housemaid, and the only one to be recovered for many days. On Tuesday the divers resumed their search. John Fox was once again sent down at the third pier of the high girders, and walked northwards along the fallen superstructure towards the fourth pier, discovering nothing new. For some reason Peter Harley, also employed by the Harbour Trust, was sent down at the same point and with the same result. Further to the Dundee side a diver engaged by the North British, Edward Simpson, dived by the sixth pier, where he discovered one of the spans lying on its side on the river bed, with its top facing downstream.

In the afternoon of Tuesday, the train itself was sighted for the first time. Having twice drawn a blank in the area between the third and fourth piers, Fox now tried between the fourth and fifth. Here the girder, as elsewhere, was found lying on what had been originally its eastward facing side, but this time Fox found within it one of the carriages, unexpectedly standing upright but without its roof, and with extensive damage to both windows and doors. Within the carriage Fox could make our little except for some pieces of splintered wood and torn cushions. He was, however, able to retrieve some scraps of oilcloth which when brought to the surface identified his discovery as the first class carriage, which, in the original order of the coaches had been placed behind the third class carriage at the very front of the train.103

It was not perhaps surprising, given the strength of the current at this point in the river, that most moveable items had by now been sucked out of the train and carried downstream. In the whole course of the diving operation nothing in the way of personal belongings, and no bodies at all, were found to be inside the carriages. But downstream it was a different story, and the beach at Broughty Ferry, some four miles down the river on the Dundee side, became the repository for a melancholy collection of clothing and personal effects, which were quickly transferred for identification by relatives to the mortuary set up at Taybridge Station. Some were not difficult to identify – the caps of both the engine driver and his fireman; the basket belonging to the guard, David Johnston, with his flags still in it, neatly rolled. Johnston had not been on duty that night, but had been coming into Dundee ready to take his place on the first train out on the Monday morning. There was a handbag containing a collection of personal belongings, and there was the muff which had belonged to Jessie Bain.104

The discovery of all these items, and more especially their public display, can only have added to the distress of the relatives of the victims. By this stage, there can have been no realistic hope that anyone had survived the disaster, though how many of the relatives must have envied the good fortune of Mrs Upton, whose daughter Alice was believed to have perished with the train, only for her to learn by telegram on the Tuesday that instead of travelling the girl had stayed overnight in Edinburgh, and would soon be home safe and well.

There could not be many miracles like that, and indeed there were to be no more, but those who mourned longed in their grief to receive the bodies of their relations into their care. Impatience with what The Times called the ‘barrenness of the diving operations’ resulted in the organisation of regular search parties on both sides of the river, but still the only finds were of debris from the train and the bridge, and more pathetic relics of the unfortunate passengers and crew.

The funeral of the only victim discovered so far, Ann Cruickshank, took place on Thursday 1 January, an occasion which brought out large crowds to pay their respects, and that same evening some boatmen out in the Tay found a second body, also female, but it eluded the grasp of their boathooks and sank out of sight. A fine tortoiseshell comb identified it as Jessie Bain. No more bodies were released by the river until the following Monday, eight days after the disaster, when David Johnston, the off-duty guard travelling on the train, was found. The next day, five more bodies were brought up, using grappling irons; James Leslie, a clerk in a timber firm, William Jack, a grocer, James Crichton, a ploughman, and Robert Watson, an iron moulder. In the evening they found the fireman of no. 224, John Marshall, his face terribly burned from being hurled against the furnace. On the Wednesday there were six more; David Neish, a schoolmaster from Lochee, John Sharp, a joiner, William Threlfall, a confectioner’s apprentice, Walter Ness, a saddler, William Macdonald, a sawmiller from Blackness, and a flax dresser, James Miller. On the Thursday four more – Archie Bain, Thomas Davidson, Alexander Robertson, and James Henderson.105

The following week an unusual experiment was attempted in the search – a gullible shoemaker called Barclay enlisted the help of a female clairvoyant, and the pair of them set out in a small yacht across the water. Close by a large sandbar known as the Middle Bank, the woman claimed to have detected the body of a man in dark clothing, with a watch and some coins in his pockets. A trawl was put down, but the water was too deep for it to reach the bottom.106

And so it went on until by the end of January thirty-three bodies had been recovered. In later months more were to come to the surface from time to time – the last known being washed up on the shores of Caithness nearly four months after the accident. Thirteen were never found at all. Out on the water the diving operations continued, buoyed up by the discovery of the first-class carriage. On Wednesday, the last day of 1879, Fox went back down to the carriage, though he came across nothing new either then, or on a second dive some way further north. While he was down, however, Edward Simpson began to explore the section between piers four and five, where almost at once he discovered the third-class carriage which had been next to the engine. On his second dive, close to the fifth pier, he at last came across no. 224, lying on its side within the girder, but almost completely undamaged. Later inspection was to show that the throttle was open, and that the Westinghouse brake with which the train was fitted had not been applied. Clearly, for the driver of the train, the fall of the bridge had come with no warning.107

On Thursday, three divers went down – Fox, Simpson, and one John Barclay, engaged by the railway company – but none of them found anything of significance. On Friday the weather was too bad for diving, and on Saturday all that was found was a piece of handrail from a third-class carriage, a number of carriage roof lights, and part of the handrail from the bridge itself. A new diver, William Thoms, came across a fracture in the girder south of the fourth pier, but was ordered back to the shore before he could examine it properly. On Sunday a total of five divers went down, most of them to carry on with the search of the girders which held the train. Edward Simpson found the crack in the girder discovered the previous day by Thoms, estimating it to be about 18 inches wide, and also picked up a tail light from the rear of the guard’s van. Thoms explored the first-class carriage and returned with more pieces of oilcloth and a couple of warming pans. The Harbour Trust had engaged a new diver, Charles Tate, and he began to examine, not the train, but the piers which had supported the columns under the high girders, and he found that part of the iron casing surrounding the concrete base of one of the piers had broken away, leaving the concrete exposed. More diving took place on the Monday, but without any material discoveries being made.108

THE RELIEF FUND

As the diving operations continued in that first week after the fall, and while the relatives waited for news, some progress was being made in arranging for relief for the bereaved. In an age when it was not expected that the state would step in and provide for those left destitute by the loss of a husband or father, it was expected that private charity would do something to cushion the blow, at least in the short term. On the Wednesday following the tragedy, the Town Council called a public meeting at which an account was given of the diving operations so far, and a proposal approved to set up a relief committee which would receive donations and ‘administer the funds according to the necessities of the case’. Provost Brownlie was to chair the committee, and he was able to report that already the sum of £1,980 16s. had been donated, largely made up of £500 from the North British Company, a further £500 from the directors’ own pockets, and £250 from Sir Thomas Bouch.109

In the course of time, requests were to come in to the Provost for money to relieve the distress and real hardship suffered by the dependents of those killed in the disaster. Few asked for themselves, but left it to some person of standing in the community – minister, doctor, or schoolmaster perhaps, to petition on their behalf. Thus Laura Davidson wrote from the Free Church manse in St Andrews on behalf of Mr and Mrs Sharp, the aged and infirm parents of John Sharp, their sole support before the accident. On 6 January, Aeneas Gordon, minister of Kettle parish church, interceded on behalf of Mrs Crichton, mother of James Crichton, ploughman. ‘The circumstances of this poor woman,’ he explained, ‘are singularly sad. On Friday the 26th ulto. her husband, a ploughman in Downfield Farm was buried, he himself having died suddenly on Monday 22nd, while following his cart in the field. James her son came home from the Mains of Fintry with the intention of returning early in the week to live with and provide for his mother and sisters, some of whom are at present attending the Kettle School.’ Thus also Dr Boyd of St Andrews to Provost Brownlie:

Dear Sir,

There is a poor creature here, a girl of twenty-two with a child ten weeks old, left a widow by the awful disaster. Her husband, a fine young fellow, walked away that evening to join the train at Leuchars. He was a cleaner in the employ of the railway company. Her father, Brand, has been twenty-eight years a driver in the company’s service. They are all particularly decent. She is left with a child a burden on their parents. Her mother told me they should never want while the parents could support them, and they had not dropped a hint to me, tho’ seeing them constantly, of any aid from the fund. But I have taken upon myself to bring the case before you, and I think a little help to provide mourning and the like, and generally give a lift to the poor girl, would be well bestowed.110

This approach on behalf of the cleaner’s wife brought in a cheque for £3.00, which even allowing for inflation seems not over generous. Apparently Dr Boyd thought so too, as his letter of thanks contained a further request that the Provost ‘should consider the case favourably.’ But of course there were other and no less urgent pleas for assistance. A small donation was supplied to Robert Henderson, the aged grandfather of another of the bridge’s victims, young James Smith, who had been in the habit of visiting the old man in Springfield and taking him a few comforts. Indeed he had been coming home to Dundee after just such an errand when the bridge fell. Money was found for the mother of David Watson, and the aged parents of Annie Spence.111

The sums disbursed to the relatives of the victims were generally small, and in no sense were intended to provide long-term support. For this they had to look to the North British for compensation, and it would appear that the company met its obligations in this respect. ‘It is so far consoling to know’, commented a newspaper account on the anniversary of the disaster,

that those whose breadwinners were carried down with the train were not left to face chill penury as an aggravation of their woe. The spontaneous generosity of the public provided a fund to relieve their immediate wants, and the North British Railway Company have acknowledged their responsibility by meeting the claims made against them. Almost all these claims have now been arranged, and the Railway Company deserves praise for their liberal treatment of the families of the officials of the ill-fated train, who have been dealt with on the same scale as the passengers, though legally the Company were not bound to make any settlement in their case.112

One is less impressed with the generosity of the North British when it is discovered that having settled most of the claims for compensation, the Company proceeded to ask for their contribution to the relief fund to be returned, as did the directors. In the end, out of donations totalling £6,527, less than £2,000 was spent on relief, most of the balance being sent back to the subscribers. What could not be returned was retained in the fund, which was ultimately wound up after transferring the accumulated balance to the Piper Alpha Disaster Appeal in 1988. Not that the bill for compensation was as much as it might have been either. As The Times commented with satisfaction, ‘Fortunately for the North British Railway Company no one holding a high position lost his life, and in consequence the compensation claims were very small and settled without difficulty.’113

THE SALVAGE OPERATION

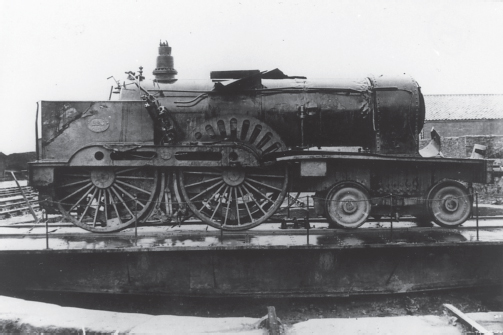

While some relief was being found for the relatives and dependents of the dead, the work of salvaging the remains of the train and the bridge continued. Bouch was still officially the engineer in charge of the bridge, and he appointed contractors to raise the fallen girders from the river bed using giant pontoons originally intended for what would have been his next great venture – the building of the bridge across the Forth. Not everything went smoothly. The girders were too big to be raised in one piece and had to be cut into manageable sections with dynamite. In an attempt to raise the fourth high girder complete with the second class carriage still trapped inside it, an explosive charge designed to free the girder damaged and sank one of the lifting pontoons. There were problems too with the engine, which Dugald Drummond was particularly anxious to recover. The plan was to lift it with pontoons and tow it to the beach at Tayport, and indeed this was done, but not before it had twice broken the lifting chains, and sunk to the bottom again. Remarkably it had suffered only superficial damage – and most of that from the lifting operation rather than from the fall. Drummond was able to report to the North British directors with some satisfaction that ‘The engine is very slightly damaged, and it will not cost more than £50 to put it in working condition. With the exception of the left hand trailing axle-bar, which has a small portion of the outer end broken, the tender is not in any way injured, and this damage will not prevent it from being serviceable.’114 In fact no. 224 was soon to be back on the rails, and continued in service for another thirty years.