Chapter 5

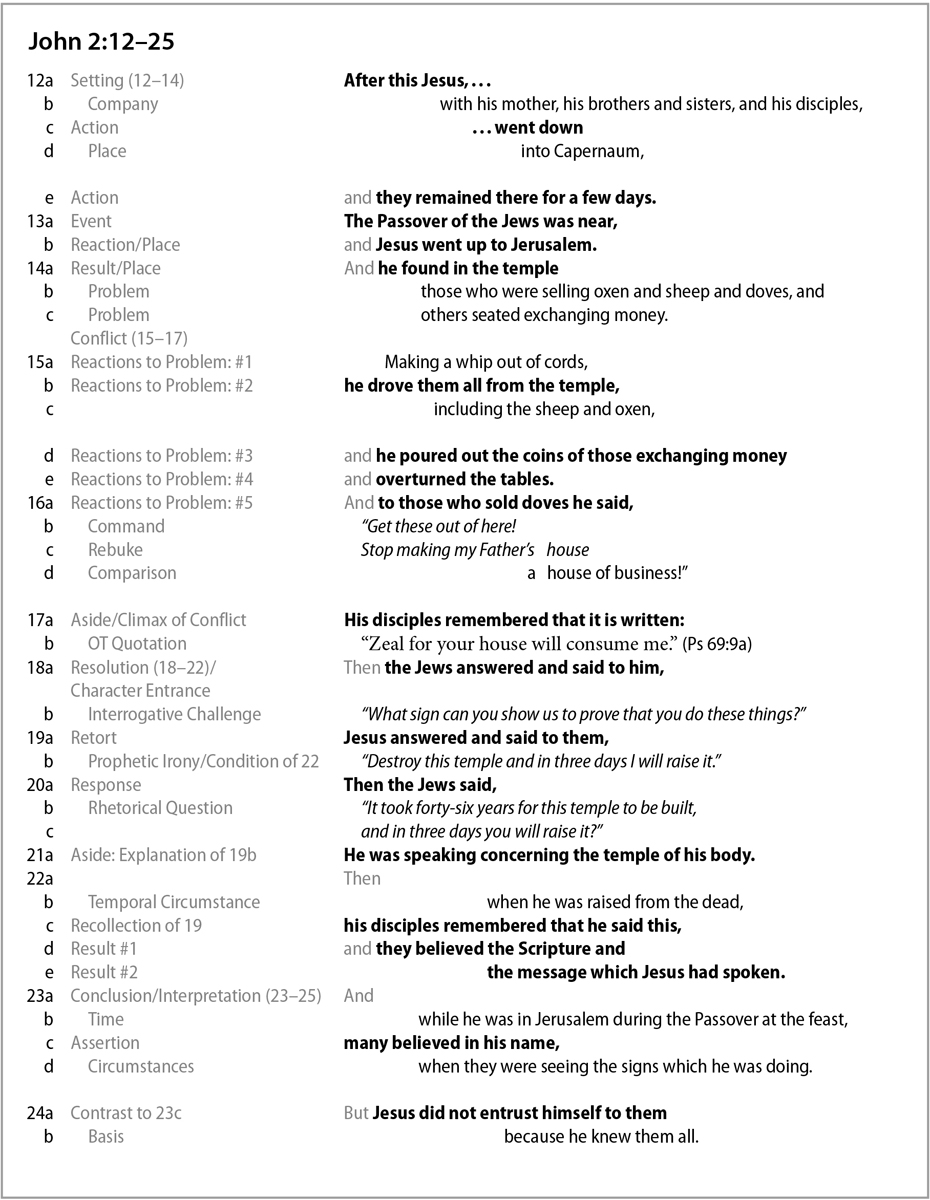

John 2:12–25

Literary Context

The narrative moves from a wedding in Cana to the temple in Jerusalem at Passover. The narrative’s careful depiction of Jesus in the previous pericope (2:1–11), with the imagery of purification followed by celebratory imagery, now confronts the reader as they watch Jesus enter into the temple. While he was willing to maintain his “guest” status at the wedding, he is not willing to remain a guest at the temple, his “Father’s house.” All of this is set in the context of the revelation of his “glory” (2:11), the theme ending the previous pericope and now pressuring this entire scene.

- III. The Beginning of Jesus’s Public Ministry (2:1–4:54)

- A. The First Sign: The Wedding at Cana (2:1–11)

- B. The Cleansing of the Temple: The Promise of the Seventh Sign (2:12–25)

- C. Nicodemus, New Birth, and the Unique Son (3:1–21)

- D. The Baptist, the True Bridegroom, and the Friend of the Bridegroom (3:22–36)

- E. The Samaritan Woman, Living Water, and True Worshippers (4:1–42)

- F. The Second Sign: The Healing of the Royal Official’s Son (4:43–54)

Main Idea

God the Father shall accept no other sacrifice than Jesus, the true Passover lamb and true temple of God. Only in Jesus can a person be reconciled to God and dwell with him. The business of the church is to sell nothing but the gospel of Jesus Christ, which is the crucified Lamb of God who alone can remove the sin and the shame of the world. Only those who receive this gospel, purchased for them by Christ, can dwell in the house of God.

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

The basic story form (see Introduction) of this pericope centers around the conflict and resolution of the temple cleansing at Passover. The introduction/setting is established in vv. 12–17, explaining the significant time (Passover) and location (temple) of the actions of Jesus in order to establish the context for the encounter with the authorities that immediately follows. Jesus’s aggressive actions in the temple (vv. 15–17) are not the conflict of the pericope but serve to express the forces at work in the actual conflict: the temple and its authority. The conflict is expressed by the brief dialogical exchange between Jesus and “the Jews” in vv. 18–20. Although not a technical dialogue (such as Jesus’s dialogue with Nicodemus), it serves a related function in this pericope (see Introduction). The resolution is provided by the narrator in vv. 21–22, serving to guide the reader to the ironic sign to which Jesus points and by which the meaning is derived from Jesus’s response to the Jews. Finally, vv. 23–25 provide the conclusion/interpretation of the pericope, carrying forward the conflict of the macrolevel plot of John that was first introduced in the prologue.

Exegetical Outline

- B. The Cleansing of the Temple: The Promise of the Seventh Sign (2:12–25)

- 1. The House of God and a House of Business (vv. 12–17)

- 2. A Challenge of Temple Authority (vv. 18–20)

- 3. The True Temple, the Body of Jesus (vv. 21–22)

- 4. Jesus’s Witness to the Nature of Humanity (vv. 23–25)

Explanation of the Text

This pericope is connected to a particular issue that has the potential of eclipsing the actual meaning intended by the text: the chronology of the cleansing of the temple. The differences in wording and setting between John and the Synoptics has caused much confusion regarding this incident (cf. Matt 21:12–13; Mark 11:15–17; Luke 19: 45–46). While Michaels is not wrong when he writes, “Such discussions belong either to canonical criticism or to the study of the historical Jesus. They are outside the scope of a commentary on any one Gospel,”1 his statement ignores the eclectic nature of exegesis, in which intra- and extratextual insights are needed to explain a text. In John there is only one temple cleansing; but that to which John witnesses demands that the possibility of two temple cleansings be addressed (and such possibilities affect what the text might be saying). The judgment of this commentary is that John speaks about a different (and earlier) temple cleansing than the Synoptics. The two-cleansing construction, we will argue, handles better not only the differences between the Gospels and their cleansings but also the nuances within the Fourth Gospel itself.

2:12 After this Jesus, with his mother, his brothers and sisters, and his disciples, went down into Capernaum, and they remained there for a few days (Μετὰ τοῦτο κατέβη εἰς Καφαρναοὺμ αὐτὸς καὶ ἡ μήτηρ αὐτοῦ καὶ οἱ ἀδελφοὶ [αὐτοῦ] καὶ οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ, καὶ ἐκεῖ ἔμειναν οὐ πολλὰς ἡμέρας). “After this” (μετὰ τοῦτο; or elsewhere with the plural: μετὰ ταῦτα) occurs frequently in John as a connective between narratives (cf. 3:22; 5:1, 14; 6:1; 7:1; 11:7, 11; 19:28, 38). This connective is imprecise, giving no indication of the timing of the events being summarized. The narrator takes care to establish the people traveling with Jesus, a surprising fact since his mother is not mentioned again until 19:25–27, and his brothers are mentioned again only in 7:3–5. “His brothers and sisters” (οἱ ἀδελφοὶ [αὐτοῦ]) is best understood to be referring to the biological children of Mary and Joseph, to his legal siblings.12 The nominative plural can refer to either all brothers or both brothers and sisters, with the latter option the most likely (cf. Matt 13:55–56; Mark 6:3).

Since Capernaum (the modern site is Tell Hum) was near the Sea of Galilee, to travel from Cana to Capernaum would naturally require a descent, thus the narrator describes that they “went down” (κατέβη). The trip from Cana to Capernaum was about sixteen miles. That Jesus and his fellow travelers stayed “for a few days” (οὐ πολλὰς ἡμέρας) suggests that there was not a long interval between the wedding they had just attended and the Jewish Passover. It is possible that John makes mention of this interlude in Capernaum, in agreement with the Synoptics (Matt 4:13; Luke 4:31), because Capernaum served as a home base for Jesus (e.g., Matt 9:1: “His own town”).

2:13 The Passover of the Jews was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem (Καὶ ἐγγὺς ἦν τὸ πάσχα τῶν Ἰουδαίων, καὶ ἀνέβη εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα ὁ Ἰησοῦς). The narrator, still introducing the scene and its setting, states that the “Passover of the Jews” (τὸ πάσχα τῶν Ἰουδαίων) was at hand. The Jewish Passover commemorated the great deliverance of the people from Egypt (Exod 12). The qualification, “of the Jews,” is common in John; the narrator elsewhere offers explanatory comments for non-Jewish readers. These qualifications, however, are not entirely consistent, for some advanced Jewish details are left unqualified, while some are applied to basic Jewish details that might even be known to the non-Jew.13 The “Passover” takes place three times in John at 2:13–23, 6:4, and 11:55 (cf. 19:14), suggesting that the ministry of Jesus took place for at least two years (hence, the typical understanding of a three-year ministry of Jesus). Such chronological precision (unique to John) should be taken into account as we consider the timing of the temple cleansing provided by the Fourth Gospel. The Passover serves to frame not merely this pericope (vv. 13, 23) but also the Gospel as a whole (19:14).

2:14 And he found in the temple those who were selling oxen and sheep and doves, and others seated exchanging money (Καὶ εὗρεν ἐν τῷ ἱερῷ τοὺς πωλοῦντας βόας καὶ πρόβατα καὶ περιστερὰς καὶ τοὺς κερματιστὰς καθημένους). This verse provides the final details regarding the setting of the pericope. The narrator depicts within the temple precincts—almost certainly the outermost court, the court of the gentiles—the business of the Jewish sacrificial religion. It is likely that the animal merchants would set up booths to meet the needs of people traveling from afar to offer sacrifices in the temple. And since many were probably from all over the Roman world, there were also some currency traders, providing foreigners with currency conversions.

The most significant detail is that this was occurring in the temple. The term becomes significant in this pericope, since its two primary NT forms both occur here. The term for “temple” (ἱερόν) that the narrator uses in vv. 14–15 is best understood to refer generally to “the whole temple precinct with its buildings, courts, etc.”14 This serves to explain the narrator’s depiction of the geographical circumstances in the pericope. The other term for “temple” (ναός), however, is primarily used to denote the dwelling place of God. It can be used comprehensively to refer to the whole temple precinct, but it does so with the emphasis on “dwelling,” not physical structure. This becomes significant since the term Jesus uses in v. 19 (followed by the Jews in v. 20 and the narrator in v. 21) is “temple” (ναός).

In the first-century Mediterranean world, corporate entities such as “the temple” and “the palace” were more than simply structures or locations for certain kinds of activities. They were invested with a social significance and therefore were personified and viewed as moral persons. “They had ascribed honor just as did any family or individual and could be insulted, cursed, hated, and dishonored. By dishonoring the temple, one also dishonored all of its personnel, from high priest down, including the One who commanded its construction and occasionally dwelled there—God.”15 For this reason, the narrative events about to be described as happening in this place are personal at numerous levels.

2:15 Making a whip out of cords, he drove them all from the temple, including the sheep and oxen, and he poured out the coins of those exchanging money and overturned the tables (καὶ ποιήσας φραγέλλιον ἐκ σχοινίων πάντας ἐξέβαλεν ἐκ τοῦ ἱεροῦ, τά τε πρόβατα καὶ τοὺς βόας, καὶ τῶν κολλυβιστῶν ἐξέχεεν τὸ κέρμα καὶ τὰς τραπέζας ἀνέτρεψεν). The narrator describes with graphic detail the response of Jesus to what he found in the temple courts. Only John notes that he was “making a whip” (ποιήσας φραγέλλιον). Such on-the-spot ingenuity reflected the dire necessity of the situation. Although “them all” (πάντας) refers primarily to the men, denoted by the masculine, since the term for “whip” (φραγέλλιον) implies that it is the sort used for driving cattle, “them all” can include both merchants and their animals.16 This scene includes no unnecessary detail for John: the sacrificial Lamb himself replaces the sacrificial animals in the temple. The specific inclusion of the “sheep and oxen” is to make clear that a full cleansing was needed; all blood (of man or animal) was deemed inadequate and tarnished save one. In light of their removal, the strong handling of their equipment makes clear that Jesus’s concern is not with trade itself but the location of this trade: “in the temple” (v. 14). The imagery is again significant. Jesus was attacking explicitly the corruption that had turned the sacrificial system into a business and attacking implicitly the failings of the sacrificial system itself.

2:16 And to those who sold doves he said, “Get these out of here! Stop making my Father’s house a house of business!” (καὶ τοῖς τὰς περιστερὰς πωλοῦσιν εἶπεν, Ἄρατε ταῦτα ἐντεῦθεν, μὴ ποιεῖτε τὸν οἶκον τοῦ πατρός μου οἶκον ἐμπορίου). After removing the men and their larger animals, the comment to the dove sellers seems less necessary. Yet it is in his final statement to the dove sellers that Jesus gives the reason for his whole action: the abuse of his Father’s house. The negation with a present imperative, “stop making” (μὴ ποιεῖτε), is used to stop action that is already taking place.17 We are not to see this statement as occurring following the removal of all traders except for the dove sellers. Rather, Jesus’s words “are to be read as more or less simultaneous with his actions.”18 By giving the reasoning last, John has made sure that we grasp the explanation as a commentary on the action of judgment already accomplished.

The force of Jesus’s statement comes when he sets his Father’s “house” in opposition to a “house of business” (οἶκον ἐμπορίου). Since the Greek phrase is a descriptive (or epexegetical) genitive, it is often translated as simply “market place,” which does not allow the English reader to see the play on the word “house” (οἶκος).19 The play on “house” makes the place, not the activity, the focus of attention. In contrast to the Synoptics’ cleansing, Jesus here is not objecting to their dishonesty (cf. Mark 11:17: “a den of robbers”) but to their presence. The contrast is sharpened when Jesus describes the temple as “my Father’s house.” Although this is the first occurrence of “my Father” by Jesus, it is anything but foreign in light of the prologue (1:14, 18). This subtle hint to the onlookers (since faithful Jews would have probably felt comfortable using the phrase) is a clear reminder of the source of the authority that Jesus has for his action (see Isa 56:7; Zech 14:21).20

2:17 His disciples remembered that it is written: “Zeal for your house will consume me” (ἐμνήσθησαν οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ ὅτι γεγραμμένον ἐστίν, Ὁ ζῆλος τοῦ οἴκου σου καταφάγεταί με). While this statement by the narrator might seem to be intended to explain the actions of Jesus, they are better understood to be shedding light on the conflict to come. It is difficult to know if this statement is suggesting the disciples remembered the OT text at that moment or only later. In light of v. 22 and 12:16, this is almost certainly a later, reflective statement. Until this verse, the disciples were entirely unimportant to the scene. This intervention by the narrator serves to provide an interpretive transition to the Scripture they remembered. The Scripture, then, becomes the interpretive grid through which the actions of Jesus are to be understood.

The Scripture the disciples remembered is from Psalm 69:9. The larger context of this quotation brings clarity to its use in this pericope. The psalmist declares in v. 7 that it is on account of God that “shame [dishonor] covers my face,” and in v. 8 he states, “I am a foreigner to my own family, a stranger to my own mother’s children.” The emphasis on the unique relation to God and the distance between his mother’s offspring connects directly to how Jesus is depicted thus far in the Gospel. The psalmist is declaring that the people were reviling God by their worship, and his public protest has caused them to begin to revile him as well. The people do not understand the protest, “and they attack the suppliant for suggesting that they are attacking Yhwh or because they infer admission of personal sin.”21 Thus, the use of Psalm 69:9 depicts both what Jesus intended by his actions (i.e., a pure temple; a right relationship with God for the people) and what Jesus received from his actions (i.e., shame) in the temple.22 In this way the setting and context of the pericope is introduced. God in the person of Jesus has just entered his temple, declared it unclean, and has prepared to receive its shame himself.

2:18 Then the Jews answered and said to him, “What sign can you show us to prove that you do these things?” (Ἀπεκρίθησαν οὖν οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι καὶ εἶπαν αὐτῷ, Τί σημεῖον δεικνύεις ἡμῖν, ὅτι ταῦτα ποιεῖς;). The conflict of the pericope is forcefully introduced to the reader. Although the Jews appear without explanation, their intentions are clear after the narrator’s inclusion of Psalm 69:9. They are the revilers who both revile God and will shame Jesus. The commotion caused by the cleansing in the court forced the authorities to present themselves. The authorities that appear, “the Jews” (οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι), are those that the Gospel has already introduced as the representatives of Judaism (see comments on 1:19) and frequent opponents of Jesus. The Jews are asking for Jesus to authenticate his enacted claim by a “sign” (σημεῖον). Their demand is clear: “We are the authorities of the temple, so by what higher authority do you claim the right to act as you have?” This question addresses the issue out of which the conflict of the pericope will find resolution.

2:19 Jesus answered and said to them, “Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Λύσατε τὸν ναὸν τοῦτον καὶ ἐν τρισὶν ἡμέραις ἐγερῶ αὐτόν). Without hesitation, Jesus directly states the proof of his authority. The content of the sign is made clear by the grammar. The imperative “destroy” (λύσατε) is best understood as a conditional imperative. The idea is that “if X, then Y will happen,” but by stating the conditional aspect of the mood the force of the imperative risks becoming eclipsed.23 And it is only when both forces, conditional and imperatival, are held together that the prophetic irony is fully expressed. The proof of the sign is conditionally dependent on the destruction of the “temple,” his body, and fulfilled when it is “rebuilt,” his resurrection, three days later (cf. vv. 21–22). At the same time, however, the command to destroy the temple (i.e., his body) is itself part of the very plan of the Father for the Son; Jesus’s command is itself a prophetic command pointing toward “the hour” of the cross (cf. 12:27, 32–33).

Interestingly, the real “sign” given to the Jews—and the disciples as well (cf. v. 22)—is here declared: the destruction of “this temple” and its resurrection “in three days,” that is, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In the Gospel, the death and resurrection of Jesus cannot be separated; they are one unified event—his “glorification” (cf. 1:14; 2:11; 7:39; 12:23). Since six “signs” are explicitly as such, the “sign” about which Jesus explicitly foretells here must be the seventh and final sign by which Jesus “revealed his glory” (2:11). It is the final and conclusive proof of Jesus’s identity and authority (for a summary of the identification of the seventh sign, see comments before 20:1). Thus, the death and resurrection of Jesus is the ultimate temple cleansing, and the temple of his body is a full replacement of the temple of the Jews.

2:20 Then the Jews said, “It took forty-six years for this temple to be built, and in three days you will raise it?” (εἶπαν οὖν οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι, Τεσσαράκοντα καὶ ἓξ ἔτεσιν οἰκοδομήθη ὁ ναὸς οὗτος, καὶ σὺ ἐν τρισὶν ἡμέραις ἐγερεῖς αὐτόν;). Although the narrator will explain below that by means of his statement Jesus is referring to himself, we must not miss that Jesus’s statement taken on its own is referring to the real temple. Only this explains the response of the Jews and therefore the need for the narrator to give an explanation. To fault the Jews for taking Jesus’s statement too literally is to misunderstand the message of the pericope. The rhetorical force of John is dependent upon this truly referring to one thing and yet also to another. For this reason, the Jews heard correctly what Jesus was saying and responded with a response intended to reject the sign as well as to shame the challenger.

This rhetorical question by the Jews is itself a statement. It makes what would have been deemed an insurmountable defense of their position and status. According to Josephus, the reconstruction of the temple began in the eighteenth year of King Herod, 20–19 BC (J.W. 1.21). Forty-six years from the commencement of the work would suggest that it was around AD 27–28 when the Jews made this statement. Such a statistic would have crushed the validity of Jesus’s statement. To interpret this as anything other than a defeating counterclaim by the Jews is to misunderstand the pericope. Interpreters often speak about the overly rigid (mis)understanding of the Jews at this point. But Jesus is talking about the temple, and they do hear him correctly. In this scene, the temple is nevertheless eclipsed by the temple (1:14), and both need to be kept in view. The reader is supposed to see two temples, not one, with the former now rendered entirely obsolete. And the reader is supposed to have heard a valid defense of the old temple. Quite simply, the misunderstanding is not to understand that the Jews are defending the wrong temple.

2:21 He was speaking concerning the temple of his body (ἐκεῖνος δὲ ἔλεγεν περὶ τοῦ ναοῦ τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ). The resolution of the conflict is so significant (and complex) that the narrator interjects the necessary explanation. Comments by the narrator that provide necessary insight are common in John (e.g., 6:64, 71; 7:5, 39; 11:13, 51–52; 12:6, 33; 20:9). In every instance they serve to add insight to the scene at hand, even to the historical details. This is precisely how this comment by the narrator is functioning. The conclusion of the dialogue between Jesus and the Jews ends with the official counterresponse to Jesus’s proof or sign. The statement by the Jews and the absence of a response by Jesus are fully intended to signify that Jesus lost the challenge. In a culture built on the foundational social values of honor and shame, Jesus was shamed. Jesus did not respond because no response was warranted; in the eyes of the temple authorities, in the eyes of any bystanders, and even in the eyes of the disciples—as v. 22 will explain—Jesus was shamed. This is the only honor contest recorded in the Gospels where the verdict was not declared—and perhaps more significantly—where Jesus was not (publicly) victorious.24 Such a conclusion is not based entirely upon sociological insights or even the silence of the narrative but by the explanation provided by the narrator. The narrator provides the necessary (“unseen”) insight that no one else saw: Jesus was not referring to the Jewish temple but to the temple of his body.

This statement, then, serves as a defense of Jesus’s honor and implicitly serves to show that Jesus received shame in the eyes of everyone else present—even his disciples (cf. v. 22). As Richards explains, “John’s defense of Jesus’s honor is correct, but the appeals to other evidence indicate what the initial verdict was. Jesus lost the honor contest. He was shamed (unfairly, John argues).”25 It could be said that it was not merely unfair; it was wrong. Admittedly, however, Jesus did offer evidence that could not be proven until after his resurrection. But only after the resurrection did that become clear to the disciples, and only with this statement is that beginning to be made clear to the reader.

2:22 Then when he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he said this, and they believed the Scripture and the message which Jesus had spoken (ὅτε οὖν ἠγέρθη ἐκ νεκρῶν, ἐμνήσθησαν οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ ὅτι τοῦτο ἔλεγεν, καὶ ἐπίστευσαν τῇ γραφῇ καὶ τῷ λόγῳ ὃν εἶπεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς). The narrator makes one final statement regarding the conflict of the scene in order to provide the necessary resolution. The narrator begins by connecting what the reader was being guided to understand with the eventual conclusion drawn by the disciples. The proof Jesus offered as a sign to the Jewish authorities, his death and resurrection, served as proof, as the final “sign” regarding this event, carrying with it all the necessary significance. Although it had already begun to make sense, it was only at that “hour” when it would all come together (cf. 2:4), when the words and deeds of Jesus came to make sense of all things. It was only “when he was raised from the dead” (ὅτε ἠγέρθη ἐκ νεκρῶν) that the disciples gained full understanding. For the disciples “remembered” (ἐμνήσθησαν) what Jesus had said and therefore came to place their trust in both “the Scripture” (τῇ γραφῇ) and “the message” (τῷ λόγῳ) Jesus had spoken. The Scripture in view is almost certainly Psalm 69, though it is not wrong for the term to include the Gospel’s awareness of the larger context of the Scriptures (cf. 5:39).

What is important to see is that the disciples had come to see as authoritative and complementary the word of God and the Word of God. The “memory” of the disciples, therefore, was not in regard to something different but to the same thing, which they only later saw as having begun well before they could understand it.

2:23 And while he was in Jerusalem during Passover at the feast, many believed in his name, when they were seeing the signs which he was doing (Ὡς δὲ ἦν ἐν τοῖς Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐν τῷ πάσχα ἐν τῇ ἑορτῇ, πολλοὶ ἐπίστευσαν εἰς τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ, θεωροῦντες αὐτοῦ τὰ σημεῖα ἃ ἐποίει). The pericope ends with a few verses that provide some interpretive conclusions. The narrator explains that many people celebrating Passover in Jerusalem believed “in his name” (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ), being founded on “the signs” (τὰ σημεῖα) he was performing. But two things are perplexing. First, since only one sign is recorded (2:11), to what other signs is the narrator referring? While there is no doubt that the author of the Gospel intends for us to understand that there were many other signs that Jesus performed (cf. 20:30–31; 21:25), it is probably best understood as emphasizing the fact that Jesus performed numerous other miracles and that his words and deeds were a constant sign of sorts.

Second, and related to the first, did the “many” truly understand the signs? Perhaps this answers our initial question. What the many thought they “were seeing” (θεωροῦντες) they were likely not understanding. The disciples become primary evidence on this point. The suggestion of this verse, then, is not that the crowds understood Jesus, in sharp contrast to the temple authorities; rather, it is claiming in fact that they did not understand him. Just as the temple authorities were blinded by their own agenda and understanding of God, so also were the people. The prologue has already informed us of this irony (see 1:11).

2:24 But Jesus did not entrust himself to them because he knew them all (αὐτὸς δὲ Ἰησοῦς οὐκ ἐπίστευεν αὐτὸν αὐτοῖς διὰ τὸ αὐτὸν γινώσκειν πάντας). What was implied in v. 23 is made explicit here. Jesus knew what they did not know—he knew them! Even if creation has forgotten its Creator, the Creator has not forgotten his creation. It is significant that “Jesus did not entrust himself” (αὐτὸς Ἰησοῦς οὐκ ἐπίστευεν). This sense of “trust” or “faith” is rarely used in this sense in the NT (e.g., Luke 16:11; Rom 3:2; 1 Cor 9:17; Gal 2:7; 1 Thess 2:4; 1 Tim 1:11; Titus 1:3). The contrast between Jesus and those interested in him highlights two things. The first is correct understanding. With spiritual fervor in their hearts, faithful Jews arrived in Jerusalem to meet with God and, in the midst of their festival, began to include Jesus within their religious excitement. They do not know the “name” about which they speak because they do not know the true Passover, the true temple, the true sacrificial Lamb, or even the true God. And for this very reason they do not—even cannot—know him. True faith must reside on Jesus, the Word of God. The subjectivity of their faith means that Jesus cannot entrust himself to them—he cannot let their distortion be the object of their faith.

The second is true discipleship. The true disciple has a correct belief in Jesus. Just as the Jews were correct to hear in Jesus’s words a reference to the real temple yet wrong in their understanding of the true temple, so also did the “many” believe in Jesus without truly believing in Jesus. The assumption is that not all belief in Jesus corresponds to the belief required: not all have been given the “right” (ἐξουσία) to believe (1:12). The right to “become” (γενέσθαι) children of God requires the creative force of God ex nihilo (see comments on 1:12). Such children are a new creation, those not of this world (17:6, 16), who have received the spiritual new birth from above (3:1–11).

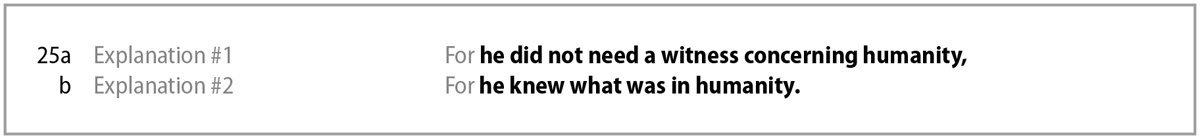

2:25 For he did not need a witness concerning humanity, for he knew what was in humanity (καὶ ὅτι οὐ χρείαν εἶχεν ἵνα τις μαρτυρήσῃ περὶ τοῦ ἀνθρώπου· αὐτὸς γὰρ ἐγίνωσκεν τί ἦν ἐν τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ). The pericope ends with what serves as a commentary on Jesus’s interaction with humanity, rooted strongly in the prologue’s preparatory description of the Light in the darkness. Rather than speaking from beyond human history, as in the prologue, we are now receiving from the narrator an explication of the state of the darkness of humanity. To make sure that we do not miss the depth of spiritual blindness, the Gospel is about to introduce to us a person who exemplifies the problem Jesus knows concerning humanity: Nicodemus.

Theology in Application

From the moment of his arrival, the person and work of Jesus have been depicted in the Gospel as the locus of divine revelation and the dwelling place of God. In this pericope, the true house of God enters the temple in Jerusalem and speaks of its fulfillment in him. Interestingly, Jesus makes this bold declaration not in the holy of holies, but in the court of the gentiles. This is itself a “sign” that “God loved the world” (3:16).

Jesus is the Temple and the Passover

The Gospel has not portrayed Jesus as merely analogous to the temple but as its full replacement. Although the new mode of worship has not yet been depicted (cf. ch. 4), the new place of worship is now fully defined in Jesus. Christ is the temple of God, and only through Christ can a person find God (cf. 14:1–7). The Fourth Gospel anticipates the temple typology found in Paul, who declares that the church is the body of Christ, the realization of God’s promise to dwell among his people (Col 1:18). Also anticipated is Revelation, where the union between Christ and the people of God finally comes to fruition in the new Jerusalem, when God’s people are fully with God in the city of God (Rev 21:3).

The cleansing of the temple is the replacement of a system that was “trading” what it did not have (the true removal of sins) for what it should not want (personal profit). Purification was God’s business; there could be no business partners in this deal. Our churches and our lives are no different. Our “religious” activities are nothing if they are not Christ centered, that is, centered upon his cross and resurrection and the significance of his work for our lives. God is not to be found in any religious practice or place; he is found only through Christ. Anything else is trading on grace, an offense that God himself deems worthy to remove.

The Importance of the Word of God

This pericope emphasizes that the disciples made connections between what they were seeing and hearing in Jesus and what had been recorded in the Scriptures (vv. 17, 22). These are not insignificant comments. Verse 22 even suggests that the disciples were putting their faith in the Scriptures; that is, they were beginning to trust the proof that, though attested long ago, was only now being made manifest. The disciples had come to see as authoritative and complementary the word of God and the Word of God. Although God has fully and decisively revealed himself in the Word, his Son, he had always revealed himself through his word, the Scriptures. The Scriptures, then, are depicted as revealing in their subject matter the person and work of Jesus Christ.

This should encourage the Christian in two ways. First, it should remind us that the Bible’s meaning and significance is found ultimately in Christ. God had planned (and worked) from the beginning to bring together all things in Christ. For this reason, the meaning of the Bible is entirely christocentric. Second, we would do well to follow the exhortation of Luther, who argued that the emphasis on the Scriptures in this pericope exhorts us “to hear, believe, and accept God’s Word gladly. . . .”26 Verse 22 makes it especially clear that to entrust ourselves to the message of Scripture is similar to entrusting ourselves to the message of Jesus. The Christian is exhorted by the narrator’s comment “to meditate industriously and continually on Scripture.”27 The ministries of our churches and the direction for our lives should be founded entirely on the Word of God.

A Passion for Christ

We get a glimpse of what motivated Jesus’s response in the temple in v. 17: zeal for the house of God. Jesus was passionate for God’s house, and he would not let it be made a marketplace or to offer things it did not have the authority to sell (i.e., the removal of sin). The memory of the disciples was not merely to the past, making sense of Jesus’s actions, but also to the future, making sense of all appropriate religious zeal. If we truly have “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor 2:16), then we are to be passionate for the things that Christ is passionate for. Since God can be concerned with nothing higher than his own glory, then we too must be passionate for his glory, which is only made visible in his Son, Jesus Christ (1:18). By definition, then, the Christian has a passion for Christ and for the things of Christ. The Christian sees his or her own life eclipsed by Christ, becoming a slave—to use Paul’s language again—to the things of righteousness, in place of sin (Rom 6:17–18). As the children of God (1:12), we begin to model our Father, enjoying what God enjoys and avoiding what God avoids, simply because we have found the love of God and guidance of the Holy Spirit so rewarding—so right—that in Christ everything makes sense.

The Celebration of Shame: From Wine to Whip

The clue to understanding the pericope above is to grasp the honor/shame conflict between the Jews and Jesus. The narrator does not want us to miss that Jesus actually lost the conflict with the Jews. Everyone knew it: the Jews, the crowd, even the disciples. Jesus lost! Such a statement sounds like it is not the story the Gospel of John was telling until we realize that “Jesus lost” is the story of the gospel—“Jesus lost” is the good news. We can too easily become like the Jews or the Pharisees or the disciples who think Jesus is their king according to their standards (e.g., military leader; financial provider). No—Jesus lost; it could be no other way. Jesus was shamed. In his temple, at his Passover, in his city, by Jewish leaders who should be serving and honoring him—by his own creation, Jesus received shame.

But this is the good news. This is God in the person of Jesus declaring through Psalm 69 that “shame covers my face” (v. 7) and that the insults of the people had fallen upon him (v. 9b). In Jesus, God entered his corrupt and negligent temple, declared it unclean, and received its shame. This is the very thing he should not have done and in light of his holiness could not have done—but he did! The contrast between the two pericopae in chapter 2 of John is stark: Jesus has gone from the master of the celebratory banquet to the shameful charlatan. The scene has moved from the Lord of the wine to the servant of the whip, and in neither case was he rightfully recognized. This is the gospel: “For the joy set before him he endured the cross, scorning its shame” (Heb 12:2). For this reason we, the children of God, exhort one another to “fixing our eyes on Jesus,” the one who authored true fellowship with God and perfected our wandering faith (Heb 12:2). To live in this gospel is to celebrate shame, holding fast to what he lost, which is our gain. We too now understand that if we are reviled because of the “name of Christ,” we are blessed, for like Jesus in the temple, “the Spirit of glory and of God rests” on us (1 Pet 4:14).