Chapter 6

John 3:1–21

Literary Context

The narrative moves from a public encounter with the temple authorities at Passover to a private encounter with a representative from the temple at night. But the issues are just as heated and just as important. This scene is best viewed as part of a larger and progressing conflict between Jesus and the ruling authorities, between God and the world. Although the arrival of Jesus, the Light, exposes the evil and darkness of the world, it is also a Light that can embrace the darkness. In this pericope, Jesus speaks as the true teacher, guiding even the religious elite to grasp the significance of his authoritative person and gracious work.

- III. The Beginning of Jesus’s Public Ministry (2:1–4:54)

- A. The First Sign: The Wedding at Cana (2:1–11)

- B. The Cleansing of the Temple: The Promise of the Seventh Sign (2:12–25)

- C. Nicodemus, New Birth, and the Unique Son (3:1–21)

- D. The Baptist, the True Bridegroom, and the Friend of the Bridegroom (3:22–36)

- E. The Samaritan Woman, Living Water, and True Worshippers (4:1–42)

- F. The Second Sign: The Healing of the Royal Official’s Son (4:43–54)

Main Idea

Jesus is the representative of God who challenges and shames the darkness of the world with its system of religion. Yet Jesus is also the manifestation of the love of God that meets the very challenge he initiated and receives upon himself the shame that belonged to the world.

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

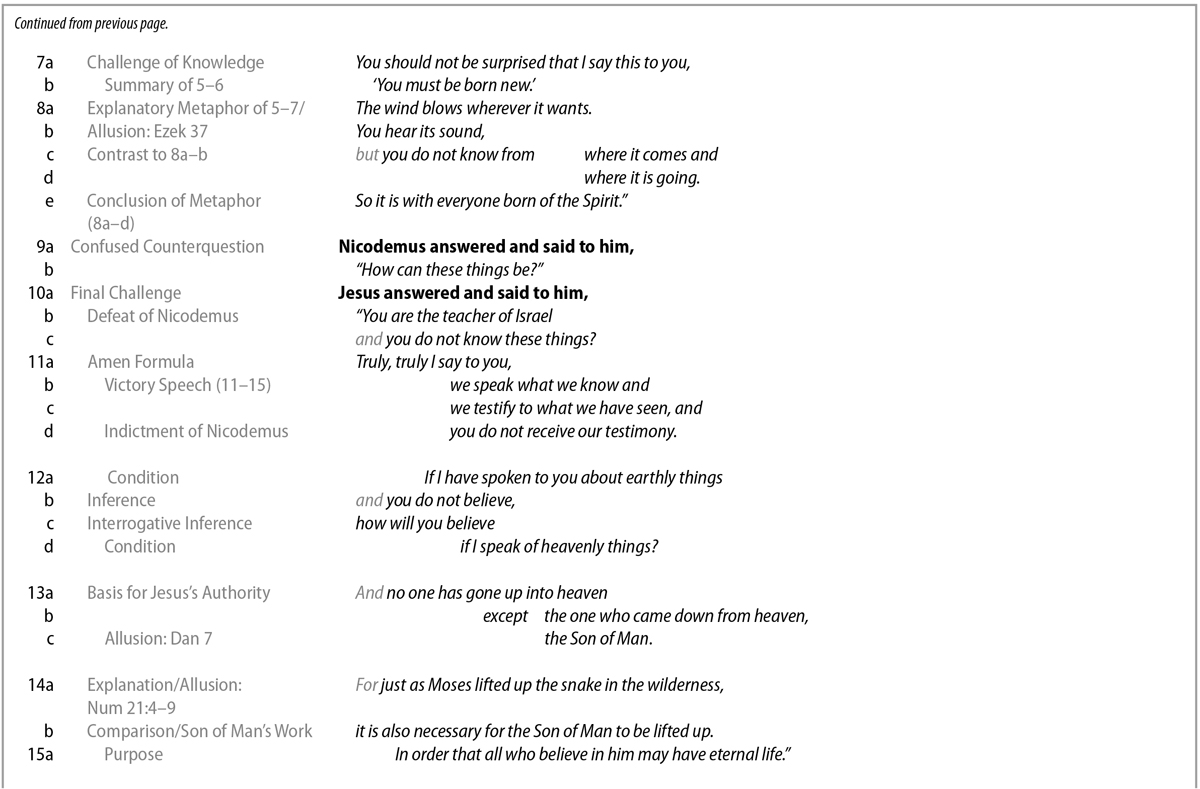

This is the first substantial dialogue in the narrative proper, and it is a social challenge dialogue, which takes the form of an informal debate intending to challenge the honor and authority of one’s interlocutor (see Introduction). In reference to this pericope, Barrett is correct when he observes that “narrative is in this section reduced to a minimum.”1 However, such a statement too easily divorces the dialogues from the narrative movement and emplotment of the Gospel as a whole. This is not a tangent for John; this is a necessary element in the developing story of Jesus.

Exegetical Outline

- C. Nicodemus, New Birth, and the Unique Son (3:1–21)

- 1. Nicodemus’s Provocative Introduction (vv. 1–2)

- 2. First Verbal Exchange: “Born New” (vv. 3–4)

- 3. Second Verbal Exchange: “Born from Water and Spirit” (vv. 5–10)

- 4. Jesus’s Victory Announcement: The Cross (vv. 11–15)

- 5. Narrator’s Commentary (vv. 16–21)

Explanation of the Text

After a compelling scene in the temple in Jerusalem at Passover in which Jesus challenged not merely the temple authorities but also the entire religious system of Judaism, the narrative moves to a more private but just as animated dialogue between Jesus and one of the temple authorities. This first dialogue, a social challenge, carries forward the plot’s depiction of the person and work of Jesus in relation not merely to religious authority, but to the foundation of the entire Jewish religion (i.e., the replaced “grace” of 1:16).

It is important to note that two transitions occur from the previous pericope to this one, both of which are a move from general to specific. First, the narrative moves from “the Jews” in a corporate sense to an individual Jew, though still a ruling official. Second, the narrative moves from “humanity/man” (2:25) in a corporate sense to an individual man. Thus, all the tension in the prologue between the Light and the darkness or God and the world is also present in this scene when Jesus confronts a representative of the opponents of God. Nicodemus embodies broken religion and broken humanity. The prologue has set the context not merely for the Gospel as a whole but even for its intricate parts.

This larger context provides insight into the nature and scope of this pericope. The scene with Nicodemus is usually considered to be a more innocent teaching moment, somehow removed from the conflict so present in the previous scenes. Nicodemus is often described as “a sincere inquirer with limited belief.”2 In fact, commentaries are nearly unanimous on this point.3 The general reconstruction goes something like this: Nicodemus comes to Jesus with a genuine openness, acknowledging that Jesus is credentialed by God. He seems to be guilty of nothing more than befuddlement before a confusing revelation, a befuddlement the reader can easily understand! At the end, Nicodemus does not argue with Jesus or depart in protest. He simply throws up his hands, asking helplessly, “How can this be?”4

But in light of the developing context of the Gospel as well as the qualification that the dialogue between Jesus and Nicodemus is in the form of a social challenge—an informal debate that is a challenge for honor and authority—the above reconstruction is misguided. As we will explain below, the encounter between Jesus and Nicodemus is part of the larger conflict between Jesus and the religious authorities, that is, between God and humanity.

3:1 Now there was a man who was one of the Pharisees, whose name was Nicodemus, a ruling official from the Jews (Ἦν δὲ ἄνθρωπος ἐκ τῶν Φαρισαίων, Νικόδημος ὄνομα αὐτῷ, ἄρχων τῶν Ἰουδαίων). The use of “man” (ἄνθρωπος) in an unusual expression is almost certainly intended to link this pericope with the closing words of the previous pericope (2:25). The insight given in 2:25, and more importantly 1:11, regarding the nature of humanity (“a man”) gives insight into the dialogue between Jesus and this “man.” This man is described as having the name Nicodemus, being from the party of the Pharisees, and having the position of one of the ruling officials of the Jews. In one sense, he is no different than any other man (2:25); in another sense, however, he is a distinct representative of the ruling authorities of the religion of God.

The narrative introduction to Nicodemus establishes for the reader the context out of which and the force with which the interaction with Jesus will take place. Verse 1 gives us three pieces of information that need explaining. First, his religious-political party: Nicodemus is a Pharisee. The Pharisees have been introduced previously and need little explanation here (see comments on 1:24). The Pharisees were strict and precise in regard to the law (Josephus, J.W. 2.162). One of the distinguishing marks of the Pharisees was commitment to “the traditions of the elders” as supplementing or amending biblical law (cf. Josephus, Ant. 13.297; Mark 7:1–13). In general, however, the Pharisees had only popular support and indirect authority, for they were neither politically connected nor aristocratic.

Second, his position and status: Nicodemus is a ruling official. This might seem to conflict with the party with which he is aligned, because the Pharisees were rarely associated with the ruling elite. In the Gospel, however, “the Pharisees” does not usually denote the Pharisaic party in general but the small number of wealthy aristocratic Pharisees who belonged to the ruling elite. This can be seen when John describes the ruling group as “the high priests and the Pharisees” (7:32, 45; 11:47, 57; 18:3). This suggests that Nicodemus comes from an elite family, and fits Josephus’s depiction of some of the Pharisees being “distinguished men” (Ant. 20.201–2). Barrett suggests, however, that John did not distinguish clearly between Jewish parties.5 Such an awkward collection suggests instead to him that the author has mistakenly fused Jewish parties and affiliations for rhetorical purposes. Another possibility, however, is that Nicodemus is a unique case. The third piece of information explains that this latter option is more accurate.

Third, his family connections: he has been given the name Nicodemus. Standing between the description of this “man” as a Pharisee and a ruling official is his name, that is, “the name given to him” (ὄνομα αὐτῷ). Commentators often draw attention to the fact that “Nicodemus” was a common Greek name.6 But even though it was a common Greek name, it was a rare name among Palestinian Jews of the first century. Bauckham has recently shown that sources reveal only four Palestinian Jews between 330 BC and AD 200 had the name Nicodemus, and all four belonged to the same family: the Gurion family.7 After reconstructing the Gurion family and seeing the clear connection between Gurion and the name Nicodemus, Bauckham concludes that Nicodemus was a member of “a single, very wealthy, very prominent Jerusalem family of Pharisaic allegiance.”8 The very name Nicodemus, which means “conqueror of the people,” along with the military meaning behind the name Gurion suggests that “the family’s unusual and distinctive names are those appropriate to military heroes. So it may be that the first Gurion or the first . . . Nicodemus was a successful general in the Hasmonean period, won the name in the first place as a laudatory nickname, and received landed estates as a reward for his distinguished service.”9

As member of the Gurion family, Nicodemus was both a Pharisee and a ruling official of the Jews, one of the ruling elite. He was wealthy, powerful, and born into an honorable and influential aristocratic family who, along with the high priests, composed the ruling group of first-century Judaism. Nicodemus, then, was a rare Jew, combining elements from the popular pietist movement of the Pharisees (he is a “teacher,” 3:10) with the wealthy and aristocratic ruling class of Judaism (he is a wealthy patron, 19:39). Such a position places Nicodemus at the very center of Judaism, as the most representative voice possible. Contra Barrett, John was not forcing foreign elements together “in order to portray Nicodemus as a representative Jew,” for Nicodemus, in light of his heritage and social-religious status, was already qualified to be the representative Jew par excellence. With this context in mind, we see Nicodemus, the perfect representative of the Jews, facing Jesus, the perfect representative of God. In this way, the narrator establishes the social-religious and theological context for this social challenge dialogue.

3:2 He came to him at night and said to him, “Rabbi, we have become aware that you are a teacher who has come from God, for no one is able to perform the signs you do unless God were with him” (οὗτος ἦλθεν πρὸς αὐτὸν νυκτὸς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Ῥαββί, οἴδαμεν ὅτι ἀπὸ θεοῦ ἐλήλυθας διδάσκαλος· οὐδεὶς γὰρ δύναται ταῦτα τὰ σημεῖα ποιεῖν ἃ σὺ ποιεῖς, ἐὰν μὴ ᾖ ὁ θεὸς μετ’ αὐτοῦ). The narrator briefly sets the stage for the challenge dialogue by describing the time at which Nicodemus approached Jesus: “at night” (νυκτὸς). Since every occurrence of “night” in John has negative associations (see 9:4; 11:10; 13:30; 21:3), it is likely that the “impression” the narrator is intending to create to set the context is derived from the cosmic depiction of darkness first established in the prologue (see Introduction). This is not to deny that the real Nicodemus approached Jesus when it was “night.” In fact, the sociological evidence would suggest that an evening event would have allowed for the dialogue to be even more public in nature.10 It is simply to suggest that in view of the prologue’s projection of the two-strand plot of John it is likely that John is pleased to have “night” impress itself upon both the historical circumstances and symbolic (cosmological) realities at play in this encounter.

Nicodemus’s opening statement to Jesus, with its honorific language, is common for a challenge dialogue. The opening address was often filled with praise for the opponent, even though it frequently turned out to be a form of self-promotion for the one who gave it.11 This opening address is a formal initiation to a social challenge dialogue. All the titles and statements reflect a recognizable form of honorific flattery, without any sense of genuineness until the dialogue continues. In the least it shows that Nicodemus takes Jesus to be a worthy interlocutor with whom he must engage.

The courteous title “Rabbi” (Ῥαββί) bestows upon Jesus the status of a professional teacher of Judaism (see comments on 1:38). The professional teaching status of Jesus is strengthened when Nicodemus also refers to Jesus as a “teacher” (διδάσκαλος). The terms in the context of first-century Judaism were connected to the spiritual guides of the people, the “scribes,” who were the only teachers of the people in matters of religion since it was deemed that the age of prophecy had ended and the will of God could only be known by a serious study of the Scriptures.12 Thus, on the lips of Nicodemus, the term suggests that Jesus is to be viewed as a religious authority to the highest degree.

If this were not enough, Nicodemus also describes this “teacher” as one who “has come from God” (ἀπὸ θεοῦ ἐλήλυθας). This is not a normal OT expression for a divine messenger (“send” is the more usual verb: cf. 1 Sam 15:1; 16:1; Isa 6:8; Jer 1:7). The preposition “from” (ἀπό) is regularly used in John to denote someone’s place of origin (1:44, 45; 7:42; 11:1; 12:21; 19:38; 21:2) and is used by both John (13:3) and the disciples (16:30) when referring to the heavenly origin of Jesus. The perfect “has come” (ἐλήλυθας) suggests an abiding presence and is frequently found on the lips of Jesus himself (5:43; 7:28; 8:42; 12:46; 16:28; 18:37).

The plain sense of these words is that Nicodemus is positing Jesus “as a new and heaven-sent interpreter of the Law and the prophets,” which rests uncomfortably with what Nicodemus should have known in regard to the one who would be a “prophet like Moses” (Deut 18:15–19).13 The uncomfortableness forces other commentators to nuance the strength of Nicodemus’s statement, showing how it is different from the details in Deuteronomy 18. Yet in the context of a social challenge dialogue, the language need not be interpreted so mechanically. Rather, the honorific language is intentionally echoing through the “prophet like Moses” motif in order to provide a show of wits and provocation. Nicodemus is initiating a “verbal contest with an ad hominem orientation.”14 With a creative maneuver, Nicodemus jabs at Jesus in a manner that on the surface sounds entirely complimentary, but at the deeper level—at the level of Scripture (for which Jesus supposedly serves as a teacher) and religious authority (which Jesus is supposedly assuming for himself)—is combative hyperbole, intending to challenge the very things it claims: Jesus’s warrant to serve as a teacher and religious authority.

This entire challenge is set in the context of a growing tension between Jesus and “the Jews” (see comments on 1:19). Nicodemus suggests as much in two ways. First, he claims to speak on behalf of others: “We have become aware” (οἴδαμεν). This serves to heighten the conflict in light of the context. “While some say this is who you are, we do not buy it!” There is no need to see the “we” as either a literary intrusion by the evangelist or a sign that Nicodemus is “betraying a touch of swagger or nervousness.”15 Rather, it connects this dialogue—this dispute—with what has come before and what is certain to follow. The “we” reflects a real conflict with the Jewish authorities, of which Nicodemus is an official member (v. 1). This also makes sense of Nicodemus’s final statement regarding the signs Jesus performs that warrant that God is with him; this serves as the grand finale of Nicodemus’s combative hyperbole.

At one level, Nicodemus’s opening address describes accurately what the common people are perceiving in Jesus’s activities (cf. 2:23). But on another level, it is exactly what “the Jews” need to confront, since the shame they tried to attribute to Jesus during the temple cleansing incident seems to have not affected him (see comments before 2:12). What was needed was a more direct and formal shaming. For this the Jews selected one of their most prominent ruling officials, a member of one of the most honorable and influential families that enjoyed a long history of “conquering” enemies of Judaism. Nicodemus is a man who was not only aristocratic but was also a Pharisee, with whom Jesus, who was known for associating with one version of the pietist movement (i.e., John the Baptist) might find familiarity. Thus the social challenge dialogue has been formally initiated.

3:3 Jesus answered and said to him, “Truly, truly I say to you, unless a man is born new, he is not able to see the kingdom of God” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω σοι, ἐὰν μή τις γεννηθῇ ἄνωθεν, οὐ δύναται ἰδεῖν τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ). Without the larger context of the social challenge, Jesus’s statement appears inconsistent. The connection is not in the words themselves but in their illocutionary intent; that is, in what they functionally intend to communicate. What appears to be disconnected is actually an immediate and forceful response to the challenge. We should not take this as an inappropriate flexing of the muscles by Jesus but as a righteous response rooted in the authority of God. If Jesus can claim the authority of God in the Jerusalem temple, certainly he can claim that same authority in a social challenge with one of the temple authorities.

Jesus begins his response to Nicodemus with an authoritative preface that connects the speaker with God himself (see comments on 1:51). Jesus declares that a man must be born “new” (ἄνωθεν). This term and our chosen translation are particularly important. While there are three possible meanings of the term, only two adverbial functions are possible here: 1) an adverb of time: again; or 2) an adverb of place: from above.16 Even though Nicodemus understands the adverb to be functioning temporally (v. 4), clearly Jesus is intending for it to function as an adverb of place. The intentional duality of this adverb has long been noted and seemed to force a difficult interpretive choice. Even if we would agree that Nicodemus did not fully understand what Jesus was meaning, he certainly heard correctly. Therefore our translation of the term must allow for this duality of meaning, since it has to mean both “again” and “from above” in v. 3. To select one of the options is to misunderstand v. 3. The intentional ambiguity of this adverb is part of the plot. In this case, the adverb is doing something that requires both its meanings to be cooperatively in play. Nicodemus was both entirely correct in what he heard and at that very same moment dead wrong.

The context of the challenge dialogue adds a further significance to the function of this adverb. The “exploitation of divergent meanings of a single word” is a common—even necessary—part of a social challenge dialogue.17 It is not only an appropriate counter to the interlocutor, but it also serves the facilitation of meaning in the developing dialogue. But Jesus is not just playing dialogue games, for his use of “again/from above” (ἄνωθεν) corresponds directly to the attack initiated by Nicodemus. In v. 2, Nicodemus used a combative hyperbole that mockingly linked Jesus to the “prophet like Moses” in Deuteronomy 18. For Nicodemus, nothing could have been further from the truth. Yet the reader knows that Jesus actually is, according to Philip in 1:45, “the one about whom Moses wrote in the Law and the Prophets.” The irony is stark. Nicodemus crafts a statement so theologically lofty that it was intended to be an obvious mockery and rebuke. Yet the one to whom it was addressed was entirely worthy of the statement. Even Nicodemus’s intended exaggeration of acclaim could not surpass or be denied Jesus.

The result of this new birth would be the ability “to see the kingdom of God” (ἰδεῖν τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ). While a Jew like Nicodemus might have primarily understood the kingdom to occur entirely at the end of the age, John (as well as the Synoptics) announces that the kingdom of God has already been inaugurated in the person and work of Jesus. The very fact “to see” is mentioned here echoes back to 1:51, where Jesus declared to his disciples that they “will see heaven open and . . . the Son of Man.” “Seeing” God (1:18) or the kingdom of God (3:3) is entirely dependent upon Jesus.

3:4 Nicodemus said to him, “How is a man able to be born when he is old? He is not able to enter into his mother’s womb a second time, is he?” (λέγει πρὸς αὐτὸν [ὁ] Νικόδημος, Πῶς δύναται ἄνθρωπος γεννηθῆναι γέρων ὤν; μὴ δύναται εἰς τὴν κοιλίαν τῆς μητρὸς αὐτοῦ δεύτερον εἰσελθεῖν καὶ γεννηθῆναι;). Nicodemus responds with a counterquestion that is often taken as affirmation that he misunderstood the ambiguous adverb. Brant suggests that it is an open question whether Nicodemus “is insensible to Jesus’s intended meaning” or whether he is actually engaging in the social challenge dialogue and “trying to foul Jesus by accusing him of crossing the bounds of truth and thereby violating the rules of play.”19 That is, does Nicodemus’s response reflect confusion (misunderstanding) or rebellion (a further challenge based upon the rules of dialogue)? It is most likely a mixture of both. Nicodemus’s categories were being annihilated, and his only response is rebellion—made manifest in a counterquestion that fails to provide an adequate response and merely serves to move the plot of the dialogue forward. Nicodemus has yet to understand what the reader has already heard in the prologue about “new birth” (1:13).20

3:5 Jesus answered, “Truly truly I say to you, unless a man is born from water and spirit, he is not able to enter into the kingdom of God” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω σοι, ἐὰν μή τις γεννηθῇ ἐξ ὕδατος καὶ πνεύματος, οὐ δύναται εἰσελθεῖν εἰς τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ). Prefacing his response to Nicodemus’s counter with another authoritative preface, Jesus declares that a person must be born “from water and spirit” (ἐξ ὕδατος καὶ πνεύματος). Several things require explanation to interpret this prepositional phrase. First, the grammar of the phrase demands that the two terms be understood in relation to each other. The fact that this phrase is taken to be an explanation of “again/from above” (ἄνωθεν) demands that the birth spoken of here is singular, not plural.

Second, the terms need to be explained by means of both their background (OT) and their foreground (John). Although the full construction is not found in the OT, “the ingredients are there.”21 With the creation motif so strong in John, it is significant that the OT begins with the statement, “The Spirit of God was hovering over the waters” (Gen 1:2; emphasis mine). More specifically, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel had all seen the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple and yet envisaged the restoration of the city and its temple. Ezekiel specifically spoke of a renewal of Israel which cleansed the people with clean water from all uncleanness and gave them a new heart and a new spirit (Ezek 36:24–28). Following Ezekiel 36 is the resurrection of a new people (Ezek 37) and the building of a new temple (Ezek 40–48). Thus Ezekiel, whose influence will also be seen in John 4 together with a score of other OT passages (e.g., Ezek 11:16–20; Jer 31:31–34) is fully adequate to account for the phrase “born of water and spirit.”

The use of “water” and “spirit” by the Gospel itself also shows a similar swath of impressions that speak to the broader motif of cleansing, restoration, and newness. “Water” in John evokes images either of cleansing (9:7; 13:5) or of sustaining life by the quenching of thirst (4:10–14; 6:35; 7:37–38) and is even directly connected to “the Spirit” in 7:39. “Spirit” in John can be either the “life-giving” Spirit (6:63) or the agent of purification (1:33). While this includes the capital-S “Spirit,” he is not the specific referent of “spirit” here at 3:5. The phrase “water and spirit” refers to the work of the Trinitarian God, which includes the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Spirit has a central role in this cleansing, but the cleansing would be entirely incomplete without the Son. Thus, “born from water and spirit” is referring to a radical new birth that yields a cleansing and renewal that is not merely from God—“from above”—but is the full manifestation of what God had promised long ago. This new birth is an eschatological birth, the cleansing and renewal par excellence. It is so overwhelmingly rooted in God that it can only be described as “from above” and explained with various OT images. Nicodemus is not only directed “to see” it (v. 3) but is invited “to enter” (εἰσελθεῖν). In Jesus what God promised has now been fulfilled. And in Jesus both spiritual realities and physical realities of the kingdom coalesce.

3:6 “That which is born of flesh is flesh, and that which is born of spirit is spirit” (τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τῆς σαρκὸς σάρξ ἐστιν, καὶ τὸ γεγεννημένον ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος πνεῦμά ἐστιν). This further statement by Jesus serves to reinforce the radical nature of the cleansing and renewal from God. The concept of flesh is not to be simplistically imported from the apostle Paul, for in John “flesh” is merely the body and its limitations, which is sharply contrasted to the source of the children of God, which is supernatural and entirely from the outside of a person (cf. 1:12–13). The point is quite simple: “flesh” and “spirit” are different spheres of reality, each producing offspring like itself.22 “Neither can take to itself the capacity of the other.”23 While the contrast is clear, it is only at the center of the contrast, at the point of their interrelation, that the gospel is presented. The one who speaks these words is the one who became flesh. Standing before Nicodemus and now confronting the reader is the “spirit”-become-flesh. It is for this reason that the prologue so intimately connected this new birth to Christ’s person and work.

3:7 “You should not be surprised that I say this to you, ‘You must be born new’ ” (μὴ θαυμάσῃς ὅτι εἶπόν σοι, Δεῖ ὑμᾶς γεννηθῆναι ἄνωθεν). In the context of the social challenge, Jesus presses further his response to the rebuke and mockery initiated by Nicodemus. Since interlocutors would often employ divergent meanings of a single word, it is likely that “water” and “spirit” (v. 5) and “flesh” (v. 6) have served to diminish Nicodemus’s ability to respond. Again, this is not an inappropriate aggression but an authoritative response to the initiating aggressor and a leader of Judaism. For this reason, Jesus reinforces his rebuke of Nicodemus and silences any kind of response. Interestingly, Jesus’s restatement of what has surprised Nicodemus is stated this time with a plural “you” (ὑμᾶς). Jesus was well aware that the one to whom he was speaking was merely the figurehead, so he speaks through him to all who have ears to hear. Jesus is not merely involved in a social challenge with one ruling official but with Judaism—indeed, with the world. Nicodemus (and those he represents) was wrong to claim in 3:2, “we know” (οἴδαμεν); the prologue has already made clear that “the world did not know him” (1:10). What the prologue foretold Jesus has now made fully known. The challenge dialogue has been turned back upon the interlocutor. Now Nicodemus is forced to face his true challenger: God himself.

3:8 “The wind blows wherever it wants. You hear its sound, but you do not know from where it comes and where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit” (τὸ πνεῦμα ὅπου θέλει πνεῖ, καὶ τὴν φωνὴν αὐτοῦ ἀκούεις, ἀλλ’ οὐκ οἶδας πόθεν ἔρχεται καὶ ποῦ ὑπάγει· οὕτως ἐστὶν πᾶς ὁ γεγεννημένος ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος). Jesus explains why Nicodemus should not be surprised about new birth in the form of an analogy regarding wind. Interpreters usually discuss how this “verse is complicated” by the use of the word “wind/spirit” (πνεῦμα), with some focusing on the (physical) wind and others the Spirit.24 The answer to this “complication” is found in the context of the social challenge. By giving an analogy that is able to exploit the flexibility of the word “wind/spirit” (πνεῦμα), Jesus not only provides a powerful explanation of the nature of new birth but does so in the form of an appropriate counter befitting the dialogue. The style is not to be dismissed as inappropriate or unneeded. In its first-century context, a social challenge dialogue was based on both principle and poetics. Jesus is showing himself to be the definitive Word.

The analogy is empowered by the contrastive traction between the two. The meaning is found not in the point of reconciliation between differences but in the one thing that both wind and spirit have in common: the mysterious, the unseen. The further apart the two might appear only enhances what they have in common, and this is exactly what Jesus stresses. The wind cannot be controlled; it contains its own power. The wind can be heard and even recognized, but it cannot be known or analyzed. Its activities, though active in and around us, are wholly other. It is at one and the same time a part of our experience and yet totally beyond us and entirely outside of what we can know and do. “So it is” (οὕτως) with the “spirit.” Jesus’s comparison is not between “wind” and lowercase “spirit,” but he has creatively necessitated that the term refer to the uppercase “Spirit.” For only the Spirit is able to provide new birth. The creative use of “spirit/wind/Spirit” (πνεῦμα) allows Jesus to explain forcefully the mysterious power and activity of the Spirit. Just as “life” is “in the Word” (1:4), so also are spiritual things empowered “by the Spirit.” The one “born of the Spirit” (ὁ γεγεννημένος ἐκ τοῦ πνεύματος), therefore, is nothing less than a mysterious, supernatural creation of God (cf. 1:12–13). Just as “water and spirit” in v. 5 was echoing Ezekiel 36, so here the playful use of the term “wind/spirit/Spirit” echoes Ezekiel 37, where the dead have “breath put in them” (v. 10). This is the nature of the new birth about which Jesus speaks.

3:9 Nicodemus answered and said to him, “How can these things be?” (ἀπεκρίθη Νικόδημος καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Πῶς δύναται ταῦτα γενέσθαι;). Nicodemus gives a second and final response to Jesus, again in the form of a question. In the context of a social challenge, this is not best viewed as an “incredulous question”25 but as a counter toward his interlocutor. It is likely that Nicodemus’s question is rejecting the terms.26 But even then, such a counter is more a move out of desperation than a competent countering statement. This question is the last and definitive statement of Nicodemus—a shockingly impotent conclusion in a social challenge dialogue. Before Jesus, silence suits him better. The historical situatedness of Nicodemus as a Pharisee and ruling official as well as his family heritage as “the conqueror” makes the scene all the more telling. The representative of the Jews is silenced before the representative of God.

3:10 Jesus answered and said to him, “You are the teacher of Israel and you do not know these things?” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Σὺ εἶ ὁ διδάσκαλος τοῦ Ἰσραὴλ καὶ ταῦτα οὐ γινώσκεις;). Jesus brings the challenge around full circle and, after receiving the honorific title mockingly bestowed upon him from Nicodemus, takes away from Nicodemus the title Nicodemus would have claimed for himself: “the teacher of Israel” (ὁ διδάσκαλος τοῦ Ἰσραὴλ). With the definite article, the title is an appropriate mockery of this God challenger who has spoken out of turn and claimed for himself a title and position that does not belong to him. The true teacher, the definitive Word of God, is the one to whom that office has already been given. While this might be viewed as hyperbole in a social challenge, the prominence of Nicodemus might suggest that Nicodemus is not far removed from this position. Jesus provides a crushing counter that completes the dialogue. In one sense, it is a rebuke of Nicodemus’s inability to see what the prophets had foretold in the Old Testament (see examples above). In another sense, it is a rebuke of Nicodemus’s vainglory, his inappropriate posture toward himself and toward God. Thus, the one who thought he was coming to shame the shameless has received the shame; the one who thought he was the teacher has become the student. Although the Gospel will give us insights into Nicodemus’s response, the silence from Nicodemus is deafening. Nicodemus became the very proof of Jesus’s point; he was not only defeated by an argument, he became the argument.

3:11 “Truly, truly I say to you, we speak what we know and we testify to what we have seen, and you do not receive our testimony” (ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω σοι ὅτι ὃ οἴδαμεν λαλοῦμεν καὶ ὃ ἑωράκαμεν μαρτυροῦμεν, καὶ τὴν μαρτυρίαν ἡμῶν οὐ λαμβάνετε). Jesus began his counter to Nicodemus with an authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51) and in the same manner he begins what can be described as his victory speech. This verse begins what in the context of a social challenge dialogue is “the vaunting at the end of a battle.”27 But in contrast to a social challenge between equals, from the start the reader has known that this was no true challenge. Thus, this is no egotistical vaunt of a fortunate winner, but the I AM, “the Maker of all things.” These postvictory comments, therefore, were rightfully his from the beginning.

After the authoritative preface, Jesus makes a strong statement that is filled with first-person plurals: “We speak what we know” (ὃ οἴδαμεν λαλοῦμεν); “we testify to what we have seen” (ὃ ἑωράκαμεν μαρτυροῦμεν), and “you [pl.] do not receive our testimony” (τὴν μαρτυρίαν ἡμῶν οὐ λαμβάνετε). On the surface, the “we” of Jesus is a perfect counter to the “we” of Nicodemus (v. 2). But more is clearly intended by the “we” spoken by Jesus. In light of the context of the Gospel, Jesus is referring to what he uniquely has seen and heard, what is uniquely his to know as “the unique Son.” He is the one who has descended from heaven (v. 13) and has seen heaven (cf. 5:19–20). “If the claim refers to the testimony that only Jesus can make on the basis of what he has seen in heaven, then not even his disciples in the future can say ‘we testify to what we have seen,’ only that Jesus testified to what he had seen.”28 This is a “we” of authoritative testimony (see comments on 1:14). The “intention is not to refer to any other persons along with the speaker, but to give added force to the self-reference . . . the plural intensifies the authority expressed.”29 Only Jesus can speak this way; there is no other person that can speak as such. Even the testimonies of the disciples are all derivative, whereas the testimony of Jesus is the very fountainhead of Christian revelation. Thus, the testimony and message of Jesus is connected to his presence with God as a person of God. Jesus is the “thus says the Lord.” And it is interesting to note that the “you” that does not receive Jesus’s testimony is plural. Although it includes with Nicodemus the Jewish authorities he represents, it extends well beyond them (i.e., the world; cf. 1:10–11).

3:12 “If I have spoken to you about earthly things and you do not believe, how will you believe if I speak of heavenly things?” (εἰ τὰ ἐπίγεια εἶπον ὑμῖν καὶ οὐ πιστεύετε, πῶς ἐὰν εἴπω ὑμῖν τὰ ἐπουράνια πιστεύσετε;). Jesus’s return to the first person “I have spoken” (εἶπον) is not to be contrasted with the authoritative “we” in v. 11, but should be seen as synonymous. His reversion is merely to bring into focus the specific dialogue he had been having with Nicodemus. Jesus presents a contrast that, by putting it in the form of a question, he deems is beyond what Nicodemus is able to grasp. The contrast is between “earthly things” (τὰ ἐπίγεια) and “heavenly things” (τὰ ἐπουράνια). It is common for commentators to see the latter as contrasting the “higher teaching,”30 or if not a contrast at least a difference “of degree.”31 But the Gospel up to this point has been careful to show the careful coalescence of these things ultimately being made manifest in Jesus. To conclude that “earthly things” cannot contain or allude to anything “spiritual” would require that Jesus had not yet said anything “earthly,” since his first words to Nicodemus were “from above.” Yet Jesus himself claims that he had been speaking of “earthly things.” Thus, “earthly” must refer to that which takes place here, to that which is connected to and related to the flesh—including the very fleshly presence of Jesus; yet it also includes the new birth that is offered to humanity. The “heavenly things,” then, would be not merely what has been inaugurated with the arrival of Jesus but the things that will arrive at the consummation of history, namely, heaven and the full-blown kingdom of God.32 The difference between the two conditional clauses lends support for this reading.33 The message of Jesus (and the Gospel), therefore, is not abstract and otherworldly but is fleshly and about the real, physical world.

3:13 “And no one has gone up into heaven except the one who came down from heaven, the Son of Man” (καὶ οὐδεὶς ἀναβέβηκεν εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν εἰ μὴ ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβάς, ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου). The authority that belongs to Jesus, an authority that gives him the right to speak of “earthly” and “heavenly” things, is an authority rooted in his heavenly origin. The “and” (καὶ) connects this verse to v. 12 and explains the nature of Jesus’s authority. The negative statement, “no one has gone up into heaven” (οὐδεὶς ἀναβέβηκεν εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν), reinforces the importance of “belief” in Jesus. Jesus is the authoritative one in both his position “with God” and in his person as God (1:1); he is “the way . . . the truth . . . the life” (14:6). Although Jesus’s language makes it sound as if he had already “gone up to heaven,” it need not be taken so mechanically; the solution is not found in appealing to the perspective of the evangelist or to the flexible use of “except” (εἰ μὴ).34 This is the voice of one who speaks of the historical and cosmological realities in a coalescing manner. Speaking historically, we would say that Jesus has not yet ascended; yet the moment we speak cosmologically we are required to say that Jesus has always been and will always be defined as the one who was “in the beginning . . . with God” (1:1) and “from above” (v. 3). There is no need to pit them against one another, for the prologue has given us a vision of the things “unseen” that find their coalescent meaning in the incarnate Jesus.

His concluding title for himself, “the Son of Man” (ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου), is used for a second time in the Gospel (see comments on 1:51). In this occurrence, however, it is not angels who are “going up and coming down,” but the Son of Man himself. With these words, Jesus reinforces the note of impossibility and human limitation which has dominated the dialogue with Nicodemus from the start, while at the same time transcending it with a clear exception: “no one . . . except” me!35 This statement confirms what the prologue declared in 1:18: only the “unique Son” can “reveal” the Father, for “no one [else] has ever seen God.” The language of ascent/descent is ultimately referring to the divine work of redemption accomplished by (and in) the Son of Man.

3:14 “For just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, it is also necessary for the Son of Man to be lifted up” (καὶ καθὼς Μωϋσῆς ὕψωσεν τὸν ὄφιν ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ, οὕτως ὑψωθῆναι δεῖ τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου). At this point, the essential and functional significance of Jesus could not be more heavenly. With this second occurrence of “the Son of Man” and with clear connections to the divine magnificence and authority so evident in the prologue, Jesus concludes his postvictory comments with a shocking twist—with the gospel. This concluding statement gives further clarification to what has come before, namely, “new birth” and the effective power of “water and spirit.” This time, however, Jesus does not speak with “earthly/heavenly” language but by allusion to an Old Testament narrative. Jesus uses the gracious provision of refuge and new life depicted in Numbers 21:4–9 as a parabolic portrayal of his work and provision.

Several points of comparison are intended to be made. First, it is clear in Numbers 21 that the Israelites were not appropriately postured before God. They grew impatient (v. 4) and spoke directly against God and his assigned leader, Moses, freely rebuking God in a manner that reflected their own pride (v. 5). Just as the Israelites mocked and rebuked God, Nicodemus mocked and rebuked Jesus. By using this narrative, Jesus was making a parallel to what was so obvious in his conversation with Nicodemus as well as to something so obvious in the very nature of humanity: enacted rebellion and sin before God.

Second, it is clear in Numbers 21 that Moses served as the intercessor between the Israelites and God. It was only to Moses that the people could turn for relief from their suffering and their situation (v. 7), and it was only through Moses that the suffering was reversed and relationship was restored. Jesus’s statement in v. 14 makes this comparison clear by making an explicit connection between the “redemptive” work of Moses and the redemptive work of Christ. There are, however, two important differences. First, the work of Moses was clearly depicted in Numbers 21:8 to be not his own doing but the gracious work of God simply funneled through him. In contrast, as much as God the Father is still entirely behind the work of Christ (cf. 3:16), it is also clear that Jesus is entirely behind the work as well. Second, the work of Moses involved something outside of himself (e.g., a staff), whereas the work of Christ necessarily involves himself, his own “flesh” (1:14). Moses’s lifting of the staff was temporary; what was needed was an intercessor who could provide a permanent “lifting” of the staff (i.e., the cross).

It is the differences between Numbers 21 and Jesus, however, that are the ground for his message to Nicodemus, serving to present the irony of the gospel. Jesus, though victorious over Nicodemus, can only truly win when he loses—when he is killed and declared the defeated. That is, the finale of Jesus’s postvictory speech is his ultimate defeat and an ultimate victory for Nicodemus. Jesus’s own carefully selected term, “lifted up” (ὑψωθῆναι), conveys a rich duality of meaning. In the context of the cross (the historical strand of the plot), the verb is able to speak of death, suffering, and defeat. But in its larger context (the cosmological strand of the plot), the verb is also able to speak of exaltation in majesty and glorification (cf. Acts 2:33). In this one word, the message of the gospel is presented. It is only in his humiliation that Jesus can be exalted and glorified. And it is at the center of this irony that humanity receives eternal life “from above”—from Jesus. To look at Jesus is to understand the necessity of the exalted Son of Man on a cross, to understand how a crucified God can become for the world the greatest thing imaginable.

3:15 “In order that all who believe in him may have eternal life” (ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων ἐν αὐτῷ ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον). Jesus concludes with a purpose summary of his work and person, denoted by “in order that” (ἵνα) with the subjunctive “may have” (ἔχῃ). In light of v. 14, this statement carries with it all the weight of the plight of humanity as well as the exaltation of the crucified God. It can only be offered after the cross, and it can only be received by those “who believe in him” (ὁ πιστεύων ἐν αὐτῷ). The nature of this life is “eternal life” (ζωὴν αἰώνιον). The addition of the qualifier “eternal” occurs here for the first time in the Gospel and is only ever used to qualify “life.” Since the prologue already defined life by means of the Word, its qualification here is necessarily related. The phrase “eternal life” speaks not merely about the quantity of life (i.e., life forever) but also the quality of life.36 Eternal life is life in Christ.

This concludes the final statement by Jesus. Although the majority of translations imply that Jesus is speaking to the end of v. 21, the expression and tone change, and the apparent change to past tense strongly suggests that the narrator takes over in v. 16 (see below). One reason why vv. 13–15 are often considered not to be Jesus’s words is because they seem disconnected from what has come before. But when understood as the end of the social challenge dialogue, these final words, belonging to Jesus by right of his victory, are remarkable. At the moment when Jesus could be heralding the honor due to him, he announces his impending shame. And it is by Jesus’s shame that Nicodemus can become victorious, albeit in a manner quite different than expected. Thus Jesus, the winner of the social challenge, claims that his true honor (the exaltation) can only come through shame (the cross). Such an explanation bridges this pericope with what has come before. While the proof of Jesus’s victory will only be in the resurrection (cf. 2:18–19), the power of his victory must go through the cross (shame). The strange irony with which Jesus ends his dialogue with Nicodemus needs to be explained by the narrator regarding its meaning and significance.

3:16 For in this way God loved the world, and so he gave the unique Son in order that all who believe in him might not be destroyed but have eternal life (Οὕτως γὰρ ἠγάπησεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν κόσμον, ὥστε τὸν υἱὸν τὸν μονογενῆ ἔδωκεν, ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν μὴ ἀπόληται ἀλλ’ ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον). This verse begins an extended reflection by the narrator. Because ancient texts did not use anything like quotation marks, the exact point of this transition is disputed. Some have suggested the voice of Jesus stopped at v. 12 and the narrator began at v. 13, but not only is the dialogue best viewed as extending through v. 15 but the language in vv. 13–15 is strongly linked to Jesus elsewhere. For example, the title “Son of Man” is reserved for Jesus’s lips alone in the Gospel (12:34 is no exception). A similar argument demands that vv. 16–21 are best viewed as the words of the narrator/evangelist; for example, the expression “unique Son” is only used by the evangelist (1:14, 18; cf. 1 John 4:9), and Jesus does not normally refer to his Father as “God” (ὁ θεὸς).

It also seems clear that vv. 16–21 echo again the great themes of the prologue. Some examples include the following: (1) the term “world,” used only once since the prologue, occurs five times in these verses; (2) “light” occurs five times in these verses—its first appearance since the prologue; and (3) “unique Son” occurs only outside the prologue in these verses. As we discussed in regard to the prologue, it was common in classic prologues that the narrator of the prologue “would continue to comment on the action of subsequent scenes.”37 We have already seen as much since the beginning of the narrative proper. In several pericopae thus far, the narrator has been guiding the reader to understand an action as a “sign” (2:11) or to understand the words of Jesus and their correct interpretation by the disciples (2:17, 21–22), and we will see such explanatory “intrusions” later as well (e.g., 3:31–36). For this reason, it is imperative that we not detach vv. 16–21 from vv. 1–15. This is not a digression or mere meditation but a necessary interpretation of the dialogue that has just taken place; it is where the narrator gives us fuller insight into the meaning and significance of the events being testified to. By this, the evangelist “provided members of his audience with the vital information that would enable them to comprehend the plot, and to understand the unseen forces . . . which were at work in the story.”38 This interpretation by the narrator reveals the “unseen” motivation behind all of God’s actions: love.

The narrator begins by giving insight into God’s actions: “For in this way God loved the world (Οὕτως γὰρ ἠγάπησεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν κόσμον). This is the first occurrence of “God” (θεὸς) since the prologue. The “for” (γὰρ) is best understood as an explanatory conjunction, serving to introduce the narrator’s comments (cf. 4:8; 6:64; 7:5; 13:11; 20:9).39 The term translated “in this way” (οὕτως) is more often taken as an adverb of degree, which serves as a “marker of a relatively high degree”: “God so loved the world” or “God loved the world so much.”40 But although οὕτως can indicate high degree when individually modifying adjectives, adverbs, and adverbial phrases, when it occurs in combination with ὥστε it serves rather to refer retrospectively and is best translated “in this way.”41 Thus, the grammatical construction of v. 16 serves not only to separate vv. 16–21 from what has come before but even facilitates a retrospective analysis and interpretation of what has come before. This not only provides further warrant for seeing v. 16 as the beginning of a narrator comment but also guides the reader to see that the statement being made in v. 16 is a retrospective summary intended to provide explanation.

What does the narrator explain? Quite simply, that the motivation behind the words and actions of Jesus, who is the Word of God, is God’s love for the world. In case the reader was confused by Jesus’s concluding statement to Nicodemus, the narrator explains it in its larger (cosmological) context with a theological proposition: everything Jesus does and says is rooted in the love of God. This is the first occurrence of “love” in the Gospel, and it is rather shocking that the object of God’s love is “the world” (τὸν κόσμον). Nowhere else in this Gospel or anywhere else in the NT is God explicitly said to “love” (ἀγαπάω) the world (on “world,” see comments on 1:10). Although the prologue implied as much, it is only after Jesus had been depicted among the darkness of the world that the narrator thought it time to reveal the deeper intentions of God. What made God come? What made God embrace human weakness and suffering? What made God endure mockery and shame? The answer is his love for the world—the very ones for whom he was enduring and suffering shame!

In light of the grammatical construction discussed above (οὕτως . . . ὥστε), although ὥστε would individually function as a result conjunction (“so that” or “with the result that”), in combination with οὕτως it now adds something more or less parallel to the earlier referent.42 In this way, v. 16 gives retrospective interpretation of what has come before in the form of two parallel statements, both speaking about the same thing. The former, denoted by οὕτως, gives the general explanatory declaration. This happened because of God’s love for the world. The latter, denoted by ὥστε, gives explanatory nuance to the former: God’s love is made manifest in what and who he gave to the world. God gave to the world the “unique Son” (τὸν υἱὸν τὸν μονογενῆ). The giving of the Son by God is the very expression of his love. The love of God is not floating in abstraction but embodied in human “flesh.”

The purpose of the love of God, of the giving of the unique Son, is that “all who believe in him might not be destroyed but have eternal life” (ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν μὴ ἀπόληται ἀλλ’ ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον). Although impending destruction in judgment is what is coming upon the darkness, a persistent theme in John (cf. 5:22–30; 8:15–16; 12:31, 47–48; 16:11), the provision offered is life. Since v. 16 is a retrospective explanation, giving meaning to what was declared previously, it is not surprising to see “life” mentioned again (see comments on 1:15). The statement of Jesus to Nicodemus is being given a cosmological commentary by the narrator. Along with the prologue we can now see that the mission of the Son is also the mission of God, and the mission field is the world, the darkness, humanity. In light of Jesus’s challenge with Nicodemus, such language rebukes an impotent religious system and offers a way beyond the darkness of humanity.

3:17 For God did not send his Son into the world in order to condemn the world, but in order to save the world through him (οὐ γὰρ ἀπέστειλεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν υἱὸν εἰς τὸν κόσμον ἵνα κρίνῃ τὸν κόσμον, ἀλλ’ ἵνα σωθῇ ὁ κόσμος δι’ αὐτοῦ). Since v. 16 gave the explanatory overview, the rest of the narrator’s comments give further clarification and application. The first clarification is to explain what the sending of the Son was not intending to accomplish. The purpose of the unique Son, denoted by the twofold use of “in order to” (ἵνα), was not “to condemn” (κρίνῃ) but “to save” (σωθῇ).

This is the first occurrence out of seven of “the Son” (τὸν υἱὸν) absolutely, that is, without any qualification (cf. 3:36; 5:19; 6:40; 8:36; 14:13; 17:1). The various titles of Jesus presented thus far have found their most natural home: the Son of God (cf. 20:31). Although later Jesus will declare that he came to condemn (see 9:39), the narrator is here describing the specific love-based sending of the Son. While condemnation is unavoidable (cf. v. 18), it is not what the love of God seeks to bring about. Condemnation is, rather, what is natural to (as the inevitable result of) darkness. What initiated the “sending” is love, not condemnation. This is not to deny a place for condemnation but to say that the sending of the Son is rooted in the love of God. This clarification sheds further light on the social challenge with Nicodemus. The intention of Jesus was not to gain his own honor at the expense of Nicodemus but to gain honor for Nicodemus at the expense of his own.

3:18 The one who believes in him will not be condemned, but the one who does not believe is already condemned, for he has not believed in the name of the unique Son of God (ὁ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν οὐ κρίνεται· ὁ [δὲ] μὴ πιστεύων ἤδη κέκριται, ὅτι μὴ πεπίστευκεν εἰς τὸ ὄνομα τοῦ μονογενοῦς υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ). The narrator transitions from speaking about “the world” to “the one.” As much as the whole world is in need of Jesus, only “the one who believes in him” may receive what he offers. The present-tense substantival particle, “the one who believes” (ὁ πιστεύων), is commonly used in soteriological contexts, speaking of the appropriate response and posture of the child of God. Although the whole world is already condemned (in darkness), there is at the same time a way through which “the one who believes” may be exonerated. And this exoneration, this love of God, is only possible for those who believe “in the name of the unique Son of God” (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα τοῦ μονογενοῦς υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ). As discussed earlier, someone’s “name” in the ancient world did not merely function as a label but said something about the character of the person (see comments on 1:12). With the additional insight of God’s intention in sending the Son, the “name” now contains within it God’s love for the world (v. 16).

3:19 This is the verdict: the Light has come into the world and humanity loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil (αὕτη δέ ἐστιν ἡ κρίσις, ὅτι τὸ φῶς ἐλήλυθεν εἰς τὸν κόσμον καὶ ἠγάπησαν οἱ ἄνθρωποι μᾶλλον τὸ σκότος ἢ τὸ φῶς, ἦν γὰρ αὐτῶν πονηρὰ τὰ ἔργα). The narrator concludes his comment in vv. 19–21 by casting the same cosmological vision developed in the prologue, with the addition of further explanations. By now, however, the reader has also gained numerous insights from the historical strand of the plot already unfolding. The narrator makes a declarative statement with the significant term “verdict” (κρίσις), which could be translated as “judgment” but more generally speaks of the judicial process that includes and culminates in a verdict. Thus, our use of “verdict” implies an ongoing judicial process.43 The prologue described the darkness of the world, but v. 19 explains it. The world manifested its darkness by its self-love and selfishness, both of which necessarily excluded God, for God should be loved and obeyed. It was only when the love of God came, when “the light” came “into the world,” that the darkness saw itself by means of contrast. It was only in the Light that humanity could see that it was in darkness (1:4–5).

3:20 For all who practice evil hate the light and do not come toward the Light, in order that their deeds may not be exposed (πᾶς γὰρ ὁ φαῦλα πράσσων μισεῖ τὸ φῶς καὶ οὐκ ἔρχεται πρὸς τὸ φῶς, ἵνα μὴ ἐλεγχθῇ τὰ ἔργα αὐτοῦ). The reason the darkness does not “recognize” the Light (1:5) is because it hates the light. And its hate is rooted in its pride; it does not want its deeds exposed. Without the light, darkness feels safe, although in reality it has already been condemned (v. 18). Not to come to the Light, then, is true disbelief.44

3:21 But the one who does the truth comes toward the Light, in order that his deeds may be made manifest as having been accomplished in God (ὁ δὲ ποιῶν τὴν ἀλήθειαν ἔρχεται πρὸς τὸ φῶς, ἵνα φανερωθῇ αὐτοῦ τὰ ἔργα ὅτι ἐν θεῷ ἐστιν εἰργασμένα). The narrator concludes with the contrast to v. 20, with one significant difference. Rather than avoiding the Light, the one who does truth comes toward the Light. The title “the one who does the truth” (ὁ ποιῶν τὴν ἀλήθειαν) is in part a contrast with the evildoer; yet it might also be an expression that describes “the one who believes.” If this is the case, then “to do the truth” is to keep the faith.45 While the evildoer finds the Light shameful, the one who does the truth embraces the Light as the place to escape shame. While the evildoer embraces who he is, the one who does truth embraces who Christ is. Finally—and this is the significant difference between the person described in v. 20 and that of v. 21—while the actions of the evildoer reflect who he is, the actions of the one who does truth reflect who God is. The purpose, denoted by “in order that” (ἵνα), is that his deeds may be made manifest “as having been accomplished in God” (ὅτι ἐν θεῷ ἐστιν εἰργασμένα). Although “through God” might seem to make more sense, “in God” (ἐν θεῷ) is more comprehensive, for the Christian life is rooted “in him” (v. 16).

Theology in Application

The arrival of Jesus has sparked a wide range of challenges, from the hesitant disciples of John the Baptist to the challenging authorities of the established Jewish religion. In this pericope, the teacher of Israel—Nicodemus—is forced to become a student, and the reader participates in a social challenge that forces upon them the choice between evil and truth, darkness and light, and a love of self and the love of God.

The Challenge of God

The context of the social challenge not only gives important insight into the details of the dialogue between Jesus and Nicodemus but also serves to set the challenge in its larger cosmological context. Like Nicodemus, the world has approached God with all its sinful pride and declared itself to be the judge of its Creator and King. Like Nicodemus, the world has crafted for itself a position of control and power that directly confronts the God of the universe. And when this world speaks of God, like Nicodemus it naively builds vaulted cathedrals and writes poetic words that simply “expose” its own darkness, its own inability to see and understand God. In his dialogue with Nicodemus, Jesus takes the challenge on directly and reverses the challenge initiated by Nicodemus so that Nicodemus’s own words turn back upon him. In the same way, God uses the darkness of the world and the shame we so quickly conceal in our pride to be the means by which we perform exactly what God wanted us to do and in the exact manner. What the world thought was a victory over Jesus at the cross became the very victory of Christ and his moment of exaltation. We crown him with thorns, and he wears them with honor! We beat him to our own benefit! The gospel—the good news—is that God has taken on our challenge, allowed us to speak in mocking hyperbole of him in our pride, and has used that for his own glory and our ultimate good.

The Love of God

It is in the very midst of a social challenge, when God has been confronted by the full, pompous brokenness of humanity, that God declared his love for the world. In one sense, this was a strange place for God to declare it, for it was wholly undeserved. Yet there was, at the same time, no better place. For it is in the deepest depth of sin that God’s love in the form of the cross of Jesus Christ makes the most sense. It is in darkness that light is most necessary and most magnificent. Ultimately, then, it was love that made God engage and counter humanity’s sinful, self-righteous challenge. God did not leave us to ourselves but came to us, extended himself to us in the form of his Son, and given us newness of life.

Oh world, embrace the love of God! Oh church, make the love of God the foundation of all life! Just as Christ during his postvictory speech over Nicodemus—when victors would traditionally declare their own brilliance and success—preferred to announce his own defeat and shame for our gain, so also we, the children of God, in moments when we appear victorious need to declare to the world the true source of our success and real reason for our life: the love of God shown in Christ. The love of God is not something to hide but to proclaim. It is not something about which we find embarrassment, for it is the embarrassment of God that makes love possible. The love of God, therefore, cannot be portrayed as abstract or vague, for in and through Jesus it is the most personal, the most “fleshly” attribute known of God.

Humanity Exposed

It was only when the Light arrived in the darkness that the darkness was exposed as darkness. And the response of the darkness to the Light made manifest its dark quality, for it did not want to be exposed. Ironically, evil is aware of its own shame, and it knows exactly what to do to stay in the dark. As the Light of humanity (1:4), Jesus has exposed the darkness of humanity. While the world speaks naively of “goodness” and “morality,” for the Christian human sinfulness and depravity are the true norm and plumb line of human existence. For this very reason, the Christian does not deny in any way their own sinfulness but wears it as a badge—not for their own honor but as proof of the work of God in one’s life. To speak of goodness or morality without Christ is to speak as a non-Christian; for the Christian is first and foremost a sinner who has been worked on by God. That is, to speak of a general morality is to speak without God and to speak about one’s own honor. The Christian finds their honor and significance in Christ, which means he or she finds acceptance and true identity as a child of God not in spite of their sin but by means of it. The motto of the Christian is “but of God” (1:13). Such a motto provides the needed contrast in regard to the old self (“but”) as well as the source of the newness of life (“of God”). Anything else is self-righteousness and idolatry.

The One Who Does the Truth

The connection between faith and behavior is located in the person and work of Jesus Christ. The reason the darkness does not “recognize” the Light (1:5) is because it hates the light. And its hate is rooted in its pride: it does not want its deeds exposed. Evil is always aware of its innate shame. Without the Light, the darkness feels safe, even though it has already been condemned (v. 18). Not to come to the Light, then, is true disbelief. The one who does the truth is the one who believes rightly about self and God. The one who does the truth knows who he is and who God is, and finds in the light the only repellant for the shame that naturally belongs to them. While the evildoer finds the light shameful, the one who does the truth embraces the light as the place to escape shame. While the evildoer embraces who he is, the believer embraces who Christ is.

It is for this reason that Christ is at once repulsive and attractive. He is repulsive because he demands a full acknowledgement of our true sin-laden selves. Yet he is attractive because he offers a “new birth.” It is so new—so different, so alien—that it can only come from God. But the attraction takes away what is repulsive. This does not mean that the Christian is able to disassociate from sin, only that sin is now different; sin is now exposed for what it is. In the light of Christ, sin becomes repulsive, something to avoid. Once in this light, the darkness becomes a place of cursing not blessing. Ultimately, then, doing the truth is a response to the love of God. To do the truth is truly to believe.