Chapter 7

John 3:22–36

Literary Context

After an intense conflict with an official representative of the Jewish authorities, Jesus continues his ministry. In light of the last three pericopae (2:1–3:21), the ministry of Jesus is now surrounded by a much larger context. Every scene depicts more clearly what the prologue described: the world does not recognize Jesus (1:5), but Jesus recognizes the world (2:25). In this scene, however, the confusion comes more from the inside, from some of the disciples of John the Baptist. With the help of the narrator (vv. 31–36), John the Baptist makes his final appearance in the Gospel and utters his most significant exhortation to his followers regarding the person of Jesus and the nature of life and ministry with him.

- III. The Beginning of Jesus’s Public Ministry (2:1–4:54)

- A. The First Sign: The Wedding at Cana (2:1–11)

- B. The Cleansing of the Temple: The Promise of the Seventh Sign (2:12–25)

- C. Nicodemus, New Birth, and the Unique Son (3:1–21)

- D. The Baptist, the True Bridegroom, and the Friend of the Bridegroom (3:22–36)

- E. The Samaritan Woman, Living Water, and True Worshippers (4:1–42)

- F. The Second Sign: The Healing of the Royal Official’s Son (4:43–54)

Main Idea

The identity of the Christian is entirely defined by Jesus, and all Christian service must be submitted to the service he already offered. For this reason, Jesus challenges not only the identity of the religious and political institutions of the world but also the identity of all Christian ministries. The task of the Christian minister is to proclaim this news in such a way that even when using their own words, it is an entirely other “Word” that is heard.

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

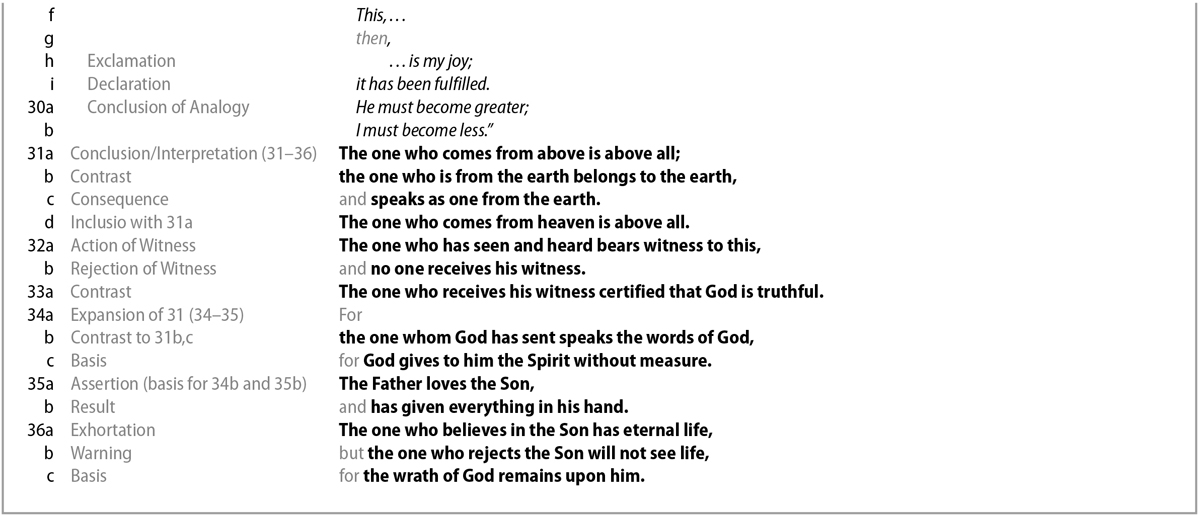

This pericope corresponds to the basic story form (see Introduction). The introduction/setting is established in vv. 22–24, explaining the place and people involved, both of which center upon John the Baptist. In vv. 25–26 the conflict is revealed by means of an argument involving John’s disciples and another Jew. The argument focuses upon the issue and gives it specific clarity for which resolution is made necessary. The resolution is given directly and forcefully in vv. 27–30 through a speech by John the Baptist. Finally, vv. 31–36 provide the conclusion/interpretation of the pericope, not merely by an implicit response by the crowd or an interlocutor but by the commentary of the narrator. Like the prologue, the narrator’s comments serve not only to explain the immediate scene but also to make connections to the developing message of the Gospel.

Exegetical Outline

- D. The Baptist, the True Bridegroom, and the Friend of the Bridegroom (3:22–36)

- 1. Introduction to the Baptism of Jesus (vv. 22–24)

- 2. Baptism Controversy (vv. 25–26)

- 3. The Bridegroom and the Friend of the Bridegroom (vv. 27–30)

- 4. Narrator’s Commentary (vv. 31–36)

Explanation of the Text

The common supposition that this pericope, or part of it, is out of place does not need to be explored. These conjectural suggestions neither rest on solid foundations nor make better sense of the larger context.1 The pericope makes sense just as and exactly where it stands. This is the fourth successive pericope to point out ways in which Jesus fulfills and surpasses Judaism: 2:1–11 (true purification), 2:12–25 (true temple), and 3:1–21 (true birth). It also serves to frame the first three chapters of the Gospel: 1:1–5 introduce Jesus as “the Word” and 3:31–36 give a conclusive definition to “the words” Jesus is in the process of speaking.2 The narrative has been guiding the reader to see Jesus correctly and to make the correct biblical connections. Everything we have read so far has entrusted us to the narrative and to the narrator who is witnessing not only to the work and person of Christ in the past but also to the work of God in the present. The Gospel of John is well aware that we, the readers, are to be included with those in the “darkness” (20:30–31).

3:22 After this Jesus and his disciples went into the Judean countryside, where he was spending time with them and baptizing (Μετὰ ταῦτα ἦλθεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς καὶ οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ εἰς τὴν Ἰουδαίαν γῆν, καὶ ἐκεῖ διέτριβεν μετ’ αὐτῶν καὶ ἐβάπτιζεν). The narrative signals to the reader the transition to a new pericope with the phrase “after this” (μετὰ ταῦτα), giving no indication of the timing of the events (cf. 2:12). Sometime after Jesus’s encounter with Nicodemus, which took place around Jerusalem (see 2:23), Jesus and his disciples left the city proper and went out into the rural parts of Judea, “the Judean countryside” (τὴν Ἰουδαίαν γῆν).3 After two intense conflicts, Jesus has now moved away from the city with his disciples and is described as “spending time” (διέτριβεν) with them. The point is not to conjecture about the nature of their time, as interesting as it would be to know what Jesus said or did with his disciples, but to be reminded that God had “made his dwelling” among them (1:14).

After informing the reader that Jesus spent time with his disciples, the narrative adds that he was also “baptizing” (ἐβάπτιζεν). This almost add-on statement has raised more than a few questions, most notably: Why was Jesus baptizing and what did this baptism signify? The “why” cannot be deferred to 4:1–2, where the narrator explains that it was not Jesus who was baptizing but the disciples (see comments on 4:2), because the third-person singular verb explicitly connects the baptism to Jesus. That is, although Christ did not physically perform the baptism (according to 4:2), he is still named as the author of the baptism. This verse provides a thematic introduction to the impending scene.

While supporters of John the Baptist might see a distinction, even competition, between the two baptisms (John’s and Jesus’s), for the Gospel there has always been only one baptism, and it was always and only a baptism from above, involving the Spirit and performed by Jesus, the true Baptist.4 For this reason, it is best to view the forthcoming comment in 4:2 not as an attempt to separate Jesus from the act of baptism but as an attempt to show that the similarity between those who are doing the baptizing, John the Baptist and the disciples of Jesus, is founded upon Jesus, who is authorizing true baptism on both accounts.5 This is why “he was baptizing” (ἐβάπτιζεν) had to be third-person singular, and why baptism in the church is always done in the name of Jesus (Acts 10:48; cf. Matt 28:19). It becomes imperative, then, that one not understand the statement “Jesus was baptizing” to be subsumed under the already existing baptism of John, as is common when viewing the events from within linear history. While it is true in one sense that John’s baptism came first, in another and more important sense Jesus/God was already well at work before John—from “the beginning” (1:1), or as John explained, “because he was prior to me” (1:30). And since John’s own beginning has already been rooted in the work of God (see comments on 1:6), it would be entirely inaccurate to view even the smallest part of John’s ministry as conflicting with and not serving under the ministry of God through Jesus Christ. John’s baptism was never cleansing in and of itself, and it is no coincidence that John is never even called “the Baptist” in the Fourth Gospel, for he cannot be the true Baptist (see comments on 1:33).

Thus, the historical chronology is misleading if it divides or disassociates John in any way from Jesus. In no real way is John any less a disciple than “the disciples” present with Jesus. And in no real way is John’s baptism any different from theirs.6 To view John’s baptism with the historical lens alone misconstrues the overt cosmological coalescence taking place at this unique point in redemptive history. John is only because Jesus was, is, and will be. There is no need for John to stop baptizing, or Jesus (through his disciples) to stop baptizing, for that matter. Baptism is not the problem; John is not the problem. Rather, it is simply that Jesus is necessary. For this reason, everything can and must carry on as before. The difference is that Jesus is now present. And his presence changes everything, even when it looks the same to the natural eye. In cooperation with 4:2, this verse makes clear that Jesus is the Baptizer, even if he was not physically performing the baptisms.

3:23 And John was also baptizing in Aenon near Salem, because there was plenty of water, and people were coming and being baptized (ἦν δὲ καὶ ὁ Ἰωάννης βαπτίζων ἐν Αἰνὼν ἐγγὺς τοῦ Σαλείμ, ὅτι ὕδατα πολλὰ ἦν ἐκεῖ, καὶ παρεγίνοντο καὶ ἐβαπτίζοντο). The narrative now shifts to John, who is described as baptizing in Aenon near Salem. The “also” (καὶ) intends to portray the baptisms as happening simultaneously. Although the location names taken together would mean “spring (fountain) near peace,” the narrative is mentioning them only so as to explain why baptisms are being performed there: “Because there was plenty of water” (ὅτι ὕδατα πολλὰ ἦν ἐκεῖ). The site is probably modern Ainun (“little fountain”), which has many springs in the region. Even more, this location lies east of Mount Gerizim and the ancient Shechem, the leading center of the Samaritans.7 Even though Jesus’s ministry was clearly underway, two indicative verbs explain that people were continually “coming” (παρεγίνοντο) and “being baptized” (ἐβαπτίζοντο) by John.

3:24 (For John had not yet been put into prison.) (οὔπω γὰρ ἦν βεβλημένος εἰς τὴν φυλακὴν ὁ Ἰωάννης). The introduction and setting of the pericope is concluded with a brief parenthetical statement. Since this event has not been told by the Gospel, this narrative aside assumes the readers were aware of not only John the person but even (at least some of) the events of his life. The snippet of information given by John is more substantially explained by the Synoptics (Matt 14:1–12; Mark 1:14; 6:14–29; Luke 3:19–20). It is warranted to assume that the Fourth Gospel was written with readers in mind who were aware of the other Gospels already (especially Mark). John may have written to avoid confusion or contradiction, or more simply to connect his witness to what had already been witnessed by the other Gospels.

Since the Gospel is concerned primarily with the person and work of Jesus, such a comment must develop the portrait of Jesus in some way. Two reasons for the comment can be posited. First, the Gospel is giving further details (not stated in the Synoptics) regarding what happened between the temptation of Jesus and the arrest of John. Such an inclusion suggests that the Gospel is much concerned with chronology and especially with the events that took place at the beginning of Jesus’s ministry. This supports the view of this commentary that it is likely that the Fourth Gospel’s placement of the temple cleansing is not loosely attached to the chronological happenings of Jesus, moved forward in the life of Jesus for theological reasons, but is directly reflecting what did in fact take place.

Second, the Gospel is showing the symbiotic relationship between the work of John and of Jesus. The narrative has created an inclusio in the first three chapters around the witness of John, serving to highlight the nature of Jesus’s ministry coming out of the OT and first-century Judaism. It also serves to highlight the Baptist and his unique role to Christ. This is not merely a chronological overlap but a symbiotic relationship that is rooted in the same work of the same God. While each has his own part to play, they are both significant in and of themselves and are both reflective of the unity of the work of God done through Jesus Christ. The pericope will continue to explain this unique symbiotic relationship in what follows.

3:25 Then a discussion arose between John’s disciples and a Jew regarding purification (Ἐγένετο οὖν ζήτησις ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν Ἰωάννου μετὰ Ἰουδαίου περὶ καθαρισμοῦ). This statement begins the conflict of the pericope (vv. 25–26). The details of the “discussion” (ζήτησις), which could also be translated as “debate” or “argument,” are not given. It could have been anything from a formal debate to nothing more than a mild discussion over a particular issue.

The discussion is between John’s disciples and an anonymous Jewish (or “Judean”) male. The prepositional phrase translated “between John’s disciples” (ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν Ἰωάννου) could be understood to contain a partitive genitive, and thus be translated “between some of John’s disciples,” but it is best viewed as referring to John’s disciples as a whole (i.e., “out of John’s disciples”). Apparently, there was discussion regarding purification, which just happened to “arise” (ἐγένετο) in the presence of John the Baptist. The significance of ἐγένετο throughout the prologue makes it difficult not to see significance here. Since this is the last occurrence of the Baptist in the Gospel, the occurrence of “came/made/arise” (ἐγένετο) here potentially forms a potent inclusio. The Baptist is about to announce what the narrative has already been showing the reader: the Gospel has always been about what God is doing (and Jesus in particular), not the Baptist (who is merely a witness). Thus, the reason for mentioning the dispute is to bring focus on purification, not on the disciples of John or the unnamed Jew. They, like the reader, are to be directed to the true meaning and source of purification. The Baptist, in what will be his final appearance, is a witness to something other, and for this to be made clearer it is time for his presence to be removed.

3:26 And they came to John and said to him, “Rabbi, the one who was with you on the other side of the Jordan, the one to whom you have been bearing witness, look, he is baptizing and everyone is going to him” (καὶ ἦλθον πρὸς τὸν Ἰωάννην καὶ εἶπαν αὐτῷ, Ῥαββί, ὃς ἦν μετὰ σοῦ πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου, ᾧ σὺ μεμαρτύρηκας, ἴδε οὗτος βαπτίζει καὶ πάντες ἔρχονται πρὸς αὐτόν). In some way, the discussion between John’s disciples and the unidentified Jew connected itself to the nearby and seemingly parallel ministry of Jesus. The disciples of John (and perhaps the unidentified Jew as well) come to the Baptist and offer a concern regarding Jesus. They address the Baptist as “Rabbi” (Ῥαββί), a term that except for this use is only applied to Jesus in the Gospel. Such a title is clearly honorific, indicating to the reader that these disciples claim allegiance to him. The narrative has allowed the reader to feel the palpable tension that was stirring around the disciples of John regarding the person and ministry of Jesus.

It is possible to interpret the statement of the disciples as arising out of jealousy or envy against Jesus in support of the Baptist. But “one must not attempt to give a psychological interpretation of the disciples’ report to John.”8 John’s disciples state unequivocally that John is witness to another, and a witness by nature points to something or someone other. The implicit problem, therefore, is not with Jesus but with the witness. What is a witness to do when the object of the witness has arrived? What is the nature of a witness? This is the conflict that has been placed at the feet of the witness, the prophet-apostle (see comments on 1:15). John has declared who he is not (see comments on 1:20); now in his last act of witnessing he must explain who he is.

3:27 John answered and said, “A man is not able to receive anything except what is given to him from heaven” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰωάννης καὶ εἶπεν, Οὐ δύναται ἄνθρωπος λαμβάνειν οὐδὲ ἓν ἐὰν μὴ ᾖ δεδομένον αὐτῷ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ). With the conflict placed before John the Baptist, his response serves to bring resolution to the plot of the pericope (vv. 27–30). The resolution the Baptist provides, however, has not always satisfied interpreters. What is given? To whom is it given? How does this explain the issue raised by John’s disciples? Carson is right to note that John casts his response in the form of an aphorism or a maxim.9 But the point is not that the Baptist is being general, vague, or cryptic but that he is speaking directly at misunderstanding (see 1:5). The Baptist declares prophetically that there is another perception that is needed—a perception “from heaven.” By this statement, the Baptist has performed the task to which he was called. It is not insignificant that “man” (ἄνθρωπος) is used here, for in perfect symbiosis with 1:6, the “man who was sent from God” has completed his task as witness. At this moment the Baptist speaks with insights similar to the prologue, situating this scene into the carefully crafted two-strand plot of the Gospel.

3:28 “You yourselves can testify concerning me that I said, ‘I am not the Christ, but I am sent before him’ ” (αὐτοὶ ὑμεῖς μοι μαρτυρεῖτε ὅτι εἶπον [ὅτι] Οὐκ εἰμὶ ἐγὼ ὁ Χριστός, ἀλλ’ ὅτι Ἀπεσταλμένος εἰμὶ ἔμπροσθεν ἐκείνου). In order to explain his position and purpose from a heavenly perspective, the Baptist reiterates what he had already declared: he is not the Christ (see comments on 1:20). By beginning with the emphatic “You yourselves” (αὐτοὶ ὑμεῖς), the Baptist makes clear that his followers are themselves recipients of his negative revelation—what he is not!—so that just as he can “witness” about Christ, they too can witness or “testify” (μαρτυρεῖτε) about him.10

From the first moment the Baptist began his ministry (according to the Fourth Gospel), his message has been about another. The entire statement is loaded with emphatics and is intended to rebuke his disciples, demote himself, and promote another. John’s disciples had conflated the witness with the one witnessed to, and in so doing had confused the message with the messenger. The difference between John and his disciples in v. 29 is not that one knew of Jesus and the others had not, for both knew of Jesus and his activity. Rather, the difference was what they knew about themselves. John had seen himself, his true identity, whereas John’s disciples had not. The Baptist’s embrace of Christ directly corresponded to his negation of self (“I am not . . .”). It was only at the point of his “not” that the Baptist could truly be who he was supposed to be, a messenger for the message and a witness to the true “I AM.”

3:29 “The one who has the bride is the bridegroom, but the friend of the bridegroom, who attends to and listens for him, greatly rejoices when he hears the voice of the bridegroom. This, then, is my joy; it has been fulfilled” (ὁ ἔχων τὴν νύμφην νυμφίος ἐστίν· ὁ δὲ φίλος τοῦ νυμφίου, ὁ ἑστηκὼς καὶ ἀκούων αὐτοῦ, χαρᾷ χαίρει διὰ τὴν φωνὴν τοῦ νυμφίου. αὕτη οὖν ἡ χαρὰ ἡ ἐμὴ πεπλήρωται). In order to explain who he is in relation to Christ, the Baptist employs the analogy of a wedding. The analogy is even more fitting in light of the Gospel’s employment of this theme earlier in 2:1–11, especially since in that pericope it was clear that at the Cana wedding Jesus was the true bridegroom, connecting the details of the pericope to the larger work of God in redemptive history (cf. Mark 2:19–20; Matt 25:1–13).

The Baptist uses the wedding analogy to state that he is the true friend of the bridegroom. While a historical reconstruction of his “position” in first-century weddings cannot be provided with exactness, it is likely that the “friend” (φίλος) of the bridegroom was the shoshbin, which is only partially comparable to a contemporary “best man” since it was much more extensive and official.11 The “friend” would be chosen with more forethought than the “master of the banquet,” who was usually one of the invited guests and was selected to oversee and preside over the celebration on the day it began (see comments on 2:8). The “friend” was a highly honored position who had numerous, important functions at the wedding, including serving as witness, contributing financially, having a prominent place in the festivities, and providing general oversight and arrangement for the ceremony. He possibly even served as the agent of the bridegroom.12 This was the role of the friend of the bridegroom, the role that John the Baptist performed for Jesus.

Besides the wedding analogy, the Baptist’s words also provide important insight regarding the scene at hand. By claiming that “the one who has [i.e., holds] the bride is the bridegroom” (ὁ ἔχων τὴν νύμφην νυμφίος ἐστίν), the Baptist is asserting that the very fact “everyone” is converging on Jesus is itself evidence that Jesus is the bridegroom of his bride—his people. The wedding analogy not only extends to God in Christ but also to the people of God in Israel and, ultimately, in the church. The OT clearly depicts Israel as the bride of the Lord: “ ‘In that day,’ declares the LORD, ‘you will call me “my husband”; . . . I will betroth you to me forever’ ” (Hos 2:16–23; cf. Isa 62:5). Interestingly, it was the duty of the “friend” to provide assistance to the bride as well, including the tasks of ensuring that the bride was bathed, appropriately dressed and adorned, and publicly escorted from her father’s house to her new home.13 In this sense, John the Baptist was the true friend of the bridegroom, who not only performed preparatory work for the bridegroom but also assisted the bride, the people of God, to be ready to receive the bridegroom. The ministry of the Baptist, then, can be viewed as a time of prewedding purification (reflected in the rite of baptism), ensuring that God’s people are appropriately dressed and adorned before they are introduced to the bridegroom.

Ironically, then, the concern the disciples of John had for their teacher was entirely misplaced. It would be like a bride who was concerned that the best man of the bridegroom was not getting any attention at the wedding. Unlike his disciples, the Baptist knew his purpose and the role he played in the wedding between God in Christ and his people, the church, among whom he was a fortunate benefactor and for whom he was a servant. For this reason, he can state that he “greatly rejoices” (χαρᾷ χαίρει; the use of the cognate dative is a rare emphatic form in Greek), for the presence of the bridegroom yields a blessing of which he is part.14 The fullness of what God has promised has been made manifest. It would be a mistake, however, to fully equate the Baptist’s joy with the “fulfillment” of his specific task.15 The Baptist’s satisfaction is not merely in what he accomplished for God but what God is accomplishing for him. At the same time that he was serving God, God was serving him. In a sense, the best thing the Baptist could do was hear and respond to his own witness. In this pericope, the Baptist shows the appropriate posture of a Christian minister, who must witness and receive the witness simultaneously.16

3:30 “He must become greater; I must become less” (ἐκεῖνον δεῖ αὐξάνειν, ἐμὲ δὲ ἐλαττοῦσθαι). The Baptist’s last words in the Fourth Gospel provide a universal summary of the purpose behind his sending from God (1:6) and a universal statement for all messengers of the message. The central term is “must” (δεῖ), which posits a divine necessity. Just as surely as God requires that a person “must” be born new (3:7) and that the Son of Man “must” be lifted up (3:14), so God requires that Jesus “must” come first and John the Baptist (or any other believing disciple) second.17 The strong contrast between “he” (ἐκεῖνον) and “I” (ἐμὲ) does not create a tension but is a natural reflection of the symbiosis between the witness and his object, in which “the one is fulfilled and made good by the other.”18

It is in this way that John the Baptist departs from the story the Fourth Gospel tells. There is no need to tell, like the Synoptics (cf. Matt 14:1–12), the end of the Baptist’s life and career, for it was at this moment that he had already given of himself. Regarding the “increase” language, it must not be taken too rigidly as if Jesus needed to increase (in glory, for example). Rather, to increase for Jesus means he becomes the one who gives, and to decrease for the Baptist means he becomes the one who receives.19 Jesus is now not only the object of the witness but also the sole witness himself—for he, like the Baptist, was sent from God to make the Father known (1:18; 3:16). Even more, Jesus not only provides a better baptism than John, but he also provides a better witness (cf. 3:32). The conflict initiated by the disciples of John has now been explained to the reader. Jesus was never the problem; he was the solution.

3:31 The one who comes from above is above all; the one who is from the earth belongs to the earth, and speaks as one from the earth. The one who comes from heaven is above all (Ὁ ἄνωθεν ἐρχόμενος ἐπάνω πάντων ἐστίν· ὁ ὢν ἐκ τῆς γῆς ἐκ τῆς γῆς ἐστιν καὶ ἐκ τῆς γῆς λαλεῖ. ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ ἐρχόμενος [ἐπάνω πάντων ἐστίν]). This verse begins an extended reflection by the evangelist. We have already seen a narrator “intrusion” in 3:16–21 and should be less surprised to see one again (see comments on 3:16). There are enough stylistic similarities with 3:16–21 (e.g., words spoken about Jesus in the third person) and the prologue to convince the reader that it is again the narrator who is speaking. By these asides, the narrator “provided members of his audience with the vital information that would enable them to comprehend the plot, and to understand the unseen forces . . . which were at work in the story.”20

In light of the preceding context in which the disciples of John contrasted Jesus and the Baptist, the narrator’s intrusion also provides an explanatory contrast, though this time with the “unseen” meaning and significance about which the disciples of John were blind. As much as it appeared on the surface that Jesus and John were similar, the narrator explains that they are quite the opposite. Jesus is described as “the one who comes from above” (Ὁ ἄνωθεν ἐρχόμενος), which in whole or in part echoes several other statements in the Gospel, especially 3:13 (see comments on 3:13; cf. 1:15, 27; 3:7; 6:14; 11:27; 12:13). His origin “from above” connects directly to what was revealed about Jesus in the prologue and should be used to support the force and meaning here. His origin defines who he is in every way. Like a genealogical statement, this insight gives context to his identity. But it also describes his authority, for because he “comes from above” he “is above all” (ἐπάνω πάντων ἐστίν). The exact identity and authority of Jesus cannot be determined or fully imagined; it can only be given an approximation by means of contrast.

Thus, the narrator provides the contrast with the phrase, “The one who is from the earth” (ὁ ὢν ἐκ τῆς γῆς). In contrast to a heavenly origin, which is unlimited, an earthly origin is limited by definition. The term “earth” (γῆ) is not used in John in a derogatory manner, unlike the Gospel’s use of “world” (κόσμος), which can often carry negative connotations (see comments on 1:10). The point is not to declare the earthly as valueless but to show its subordination to the heavenly, both in origin and in type. Whatever its value, that which is earthly is finite and limited. By referring to one who “speaks” (λαλεῖ) in an earthly manner, the narrator makes a clear allusion to John the Baptist, giving the “unseen” analysis regarding a comparison between Jesus and the Baptist. Although the Baptist had already “spoken earthly” about the real difference between himself and Jesus (cf. 1:32–34), the narrator explains it even further. The difference cannot be contained or explained by a historical contrast but can only be portrayed in cosmological categories. Thus, v. 31 ends its short inclusio with a repetition of its opening clause, making emphatic the unsurpassed difference between Jesus and John, a difference in both origin and type.

3:32 The one who has seen and heard bears witness to this, and no one receives his witness (ὃ ἑώρακεν καὶ ἤκουσεν τοῦτο μαρτυρεῖ, καὶ τὴν μαρτυρίαν αὐτοῦ οὐδεὶς λαμβάνει). The one from above, Jesus, is in a superior position based upon his place of origin, which from the very start of the Gospel has been defined as “in the beginning” and “with God” (1:1). He is described with the perfect tense as having “seen” (ἑώρακεν) and with the aorist tense as having “heard” (ἤκουσεν). Although the difference in tenses is almost impossible to gauge, since the context of the communication is between the Father and the Son, it is likely that a theological distinction is in play. The distinction might be that while the perfect denotes a “seeing” that is entirely unique to the Son as the one who reveals the Father (1:18), the aorist denotes a “hearing” that is more self-revelatory and therefore more global (a constative or comprehensive aorist), in which what is heard is the very Word himself, who is now made visible to all.21 With Augustine, we might say that although in one sense the Son hears the Father (8:26), in another sense what the Son hears can be nothing other than himself, since the Son is the only Word the Father speaks.22 Beyond this intra-Trinitarian construction (including the Spirit in v. 34), the overall point is clear: the unique origin of Jesus gives him (and makes him) the final “Word” of God and the perfect “witness” to the things of God. It is not merely the baptism of John that has been surpassed; even his witness was incomplete. Yet, as the plot of the prologue has already revealed, the Son’s witness is not received. Not to receive him is not to receive his witness (1:11; 3:11); the Word is his word.

3:33 The one who receives his witness certified that God is truthful (ὁ λαβὼν αὐτοῦ τὴν μαρτυρίαν ἐσφράγισεν ὅτι ὁ θεὸς ἀληθής ἐστιν). Similar to the prologue, universal rejection is immediately followed by an offer of reception (cf. 1:10–12; 3:20–21). The person who accepts his testimony “certifies” (ἐσφράγισεν) or “gives attestation to” the witness regarding God, like a seal certifies the document upon which it is placed.23 This certification is a sort of witness “from below,” reflecting the veracity of the witness “from above”; the Word from God is acknowledged as the word for humanity. The certification reflects not the truthfulness of the witness but the truthfulness of the object of the witness, namely, God. This passage echoes directly 1 John 5:10: “Whoever believes in the Son of God accepts this testimony. Whoever does not believe God has made him out to be a liar, because they have not believed the testimony God has given about his Son.” In both cases, not to believe in the Son is to deny God himself and to make God a liar. In contrast, God is “truthful” (ἀληθής), that is to say, he is the truth (14:6; cf. 8:26). Since God is truth, we can offer him no more acceptable worship than the faithful confession that he is true.24

3:34 For the one whom God has sent speaks the words of God, for God gives to him the Spirit without measure (ὃν γὰρ ἀπέστειλεν ὁ θεὸς τὰ ῥήματα τοῦ θεοῦ λαλεῖ, οὐ γὰρ ἐκ μέτρου δίδωσιν τὸ πνεῦμα). The Father and the Son are so identified that just as the response to the Son is a response to the Father, so also the “Word” (λόγος) is the very “words” (ῥήματα) of God. It is as God that Jesus is given unlimited access to the Spirit, who is God. The phrase “without measure” (οὐ ἐκ μέτρου) is found nowhere else in the Greek language, but must mean something like the opposite of the nonnegated form, “without using a measure.”25 Although the subject of the final clause is unexpressed, it is clearly God who is implied, since he is the stated subject of the previous clause.

For this reason, we have included the implied subject “God” in our translation, helping the reader to see that Jesus is the one God sent, through whom God speaks, and to whom he gives the Spirit. To suggest that it is the Son who gives the Spirit to believers in this way not only makes little sense of the context but also dangerously imputes the “measureless” Spirit to believers in a way that lacks biblical warrant and theological precision. As Ephesians 4:7 explains, each believer is given according to the measure of Christ’s gift (κατὰ τὸ μέτρον τῆς δωρεᾶς τοῦ Χριστοῦ). Thus, the warrant or guarantee for the truthfulness of God’s witness, Jesus, is the Spirit.

3:35 The Father loves the Son, and has given everything in his hand (ὁ πατὴρ ἀγαπᾷ τὸν υἱόν, καὶ πάντα δέδωκεν ἐν τῇ χειρὶ αὐτοῦ). If the gift of the Spirit beyond limits was not enough, the narrator informs us that “everything” (πάντα) belongs to the Son. The perfect “has given” (δέδωκεν) enforces the permanence of Christ’s ownership. A nearly identical statement is made in 13:3. The Father’s love for the Son, mentioned elsewhere in the Gospel (10:17; 15:9; 17:23–26), demands that he give him all things “that the Son should be such as the Father is.”26 This is a form of self-love which, in contrast to everything humanity has ever known, is entirely worthy. By this point, the reader has been so engulfed in the intra-Trinitarian relationship provided by the narrator that the comparison between Jesus and the Baptist has long seemed trivial.

3:36 The one who believes in the Son has eternal life, but the one who rejects the Son will not see life, for the wrath of God remains upon him (ὁ πιστεύων εἰς τὸν υἱὸν ἔχει ζωὴν αἰώνιον· ὁ δὲ ἀπειθῶν τῷ υἱῷ οὐκ ὄψεται ζωήν, ἀλλ’ ἡ ὀργὴ τοῦ θεοῦ μένει ἐπ’ αὐτόν). In a fitting climax, the narrator expands the cosmological commentary to all its readers. The narrator speaks about life in the Son through belief (or the lack thereof); these themes were discussed in the earlier narrator intrusion. In fact, this statement is best viewed as a summary of what was stated in more detail previously (see comments on 3:16–21). It is worth noting that while 3:16–21 spoke of those who reject the Son as already “condemned,” here those who reject the Son continue beneath “the wrath of God” (ἡ ὀργὴ τοῦ θεοῦ).27 Logically, if the Son is the love of God, to not receive the love of God is to receive his wrath by definition. Just as the love of God is personally defined by the Son, so also is the wrath of God. “God’s wrath is not some impersonal principle of retribution, but the personal response of a holy God who comes to his own world. . . .”28

In today’s culture, it is popular to proclaim a God of love but less popular to proclaim a God of wrath. Not only does the Gospel of John disallow such a distinction, but so also does the nature of God himself—the immeasurable love of God is a necessary response to the equally immeasurable wrath of God. The use of the present tense “remains” (μένει) suggests that what is portrayed historically (in linear time) as something to occur at the end of time is cosmologically already in play, with no need for the two times to be collapsed. This is denoted by the grammar itself. The one who believes “has” eternal life (present tense), while the one who rejects the Son “will not see” life (future tense). Bultmann is right when he states that this “conclusion is less a promise than a warning.”29 In this way, the narrator intrusion ends, providing not only a commentary on the state of the disciples of John but for all potential seekers of God.

Theology in Application

The arrival of Jesus has sparked a wide range of challenges and questions, but the scene shift from an intense challenge dialogue with Nicodemus to a puzzling question from the disciples of John forces upon the reader a deeper question regarding the identity of God’s opponents. It was clear that Nicodemus was on the wrong side of the challenge. But John’s disciples had committed themselves to his ministry and stood in agreement with his witness to Jesus. And yet, the conflict posited by this pericope between John the Baptist and Jesus found its source not in the Baptist or in Jesus but in the disciples of John. Somehow a concern for good things turned into a concern for self. It is to this issue that the Fourth Gospel turns and employs its authoritative narrative to ensure that the reader not merely be exposed to the light emanating from Jesus but also to the darkness contained in humanity.

Jesus Must Increase

Augustine is right when he suggests that to increase for Jesus means he becomes the one who gives. Everyone else can only decrease, that is, become the recipient of what he offers. At the wedding, the bride (the church) is only concerned with her bridegroom (Jesus); all the other guests, even our parents who brought us to this day (Abraham, Moses, David, the prophets, even the Baptist) all fade away as the bride approaches the bridegroom. No one else matters—and no one else should. The wedding analogy uses the pinnacle of human relationship to highlight the unique bond between Jesus and his church (corporately and individually), but it also highlights the necessity for complete monogamy. The Christian is exhorted to commit oneself to fidelity to Jesus even when the world provides its own select offerings. To receive from another, to unite oneself with another partner, is not merely adulterous but exhibits a lack of faith, for it reveals that the person does not really think that Jesus is “above all” (v. 31) and does not really have “everything” to offer (v. 35).

The God Who Is True

The reason why Jesus must increase is because he is our access to the God who is truthful (v. 33). This pericope gives grand insight into the God of the universe, not only in regard to his heavenly origin and universal authority (vv. 31–32, 35) but also in regard to the wonderful mysteries of the Trinitarian God. The Son is in a position that is unique (v. 32). He is in full and unhindered communion with the Spirit and has been given everything the Father can give, including the love of the Father. The Father does not do anything without the Son, and the Spirit is entirely defined by his empowerment of the Son. This mystery is the cause of the beauty of the universe and depicts in human words the glory of God that cannot be grasped by the human mind. The marital union between the church and Christ is merely a symptom of the perfect union between the Father, Son, and Spirit. And the “life” offered to us through the Son (v. 36) is life in the Trinitarian God. May this be the fulfillment of our “joy” (v. 29)!

The Message and the Messenger

The Christian message is at its core very personal. It involves the whole person—not merely his mind but also his life. The ministry of the Christian intrudes on all areas of life. For that reason, the Christian must make sure that the message he proclaims is the gospel of Jesus Christ and not some other, potentially attractive “good news.” The way this becomes confusing is when the gospel gets mixed with the symptoms of the gospel. Examples abound, and each would need to be subjectively explored, but the point is that the message is not the messenger. The Christian life is not about getting God into your story, but about getting your life into God’s story. To confuse your story with God’s is to confuse the gospel, to confuse the message with the messenger. It is, like the disciples of the Baptist, to begin to sense conflict when Jesus is around—when the commands and demands of Jesus feel restrictive and unnecessary. The moment that this happens, the center has moved. Remember, brothers and sisters, you are not the center, God is.

The Christian Vocation

John the Baptist was at one and the same time the “friend” of the bridegroom as well as a member of the “bride,” the people of God. The Christian has a similar calling as John’s. He or she is to proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ throughout the world (Matt 28:18–20). This is the task of the friend of the bridegroom. Yet, each Christian needs to maintain an appropriate balance between serving Christ (as the “friend”) and being served by Christ (as part of the “bride”). Even more, both positions are necessary for the Christian life—to be appropriately involved in the wedding of God. An absentee bride or friend of the bridegroom is ruinous for a wedding. Not only must the Christian see the need for both sides of the Christian life—the passive and the active—but also the inadequacy of either one on its own.

The friend of the bridegroom is fully defined by his service to the bride and the bridegroom. In a sense, his work is self-benefitting, for his joy is found in the bridegroom (v. 29) and his service benefits his own body, the church. Like the Baptist, the friend’s entire mission is centered upon what is needed for the bridegroom. In contemporary culture, it can become easy to think and act like a consumer, to focus our affections on what we desire and what makes us comfortable and happy. A friend of a bridegroom knows that this day—every day—is the day of the bridegroom. The friend knows who he is and who the bridegroom is and finds fulfillment in nothing else (v. 29). The friend of the bridegroom lives in his own witness, which has Jesus Christ as its object and eternal life as its promise.