Chapter 14

John 6:22–71

Literary Context

This lengthy pericope in the form of a dialogue has been anticipated through the previous two pericopae: the feeding of the large crowd (6:1–15) and the encounter with the “I AM” on the sea (6:16–21). From the beginning of the Gospel, Jesus has been intimately connected to God (cf. 1:1), and the previous pericope gave a vivid demonstration of the unity of God and Jesus, the “I AM” in the burning bush and on the sea. As much as this pericope completes the larger picture of chapter 6, it also propels the Gospel’s narrative forward, forcing the reader to confront the person of Jesus as the fullness of God. Jesus has confessed in dramatic fashion his true identity; he will now challenge his interested followers to see if they are willing to accept him as he truly is.

- IV. The Confession of the Son of God (5:1–8:11)

- A. The Third Sign: The Healing of the Lame Man on the Sabbath (5:1–18)

- B. The Identity of (the Son of) God: Jesus Responds to the Opposition (5:19–47)

- C. The Fourth Sign: The Feeding of a Large Crowd (6:1–15)

- D. The “I AM” Walks across the Sea (6:16–21)

- E. The Bread of Life (6:22–71)

- F. Private Display of Suspicion (7:1–13)

- G. Public Display of Rejection (7:14–52)

- H. The Trial of Jesus regarding a Woman Accused of Adultery (7:53–8:11)

Main Idea

Jesus is not only the source of life; he is also its substance. The mystery of the metaphor of eating his flesh and drinking his blood is comfortably solved in the simplicity of belief in him and his work on the cross. As the bread of life, Jesus offers himself as the satisfying gift of God and offers a challenge against human pride and disbelief.

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

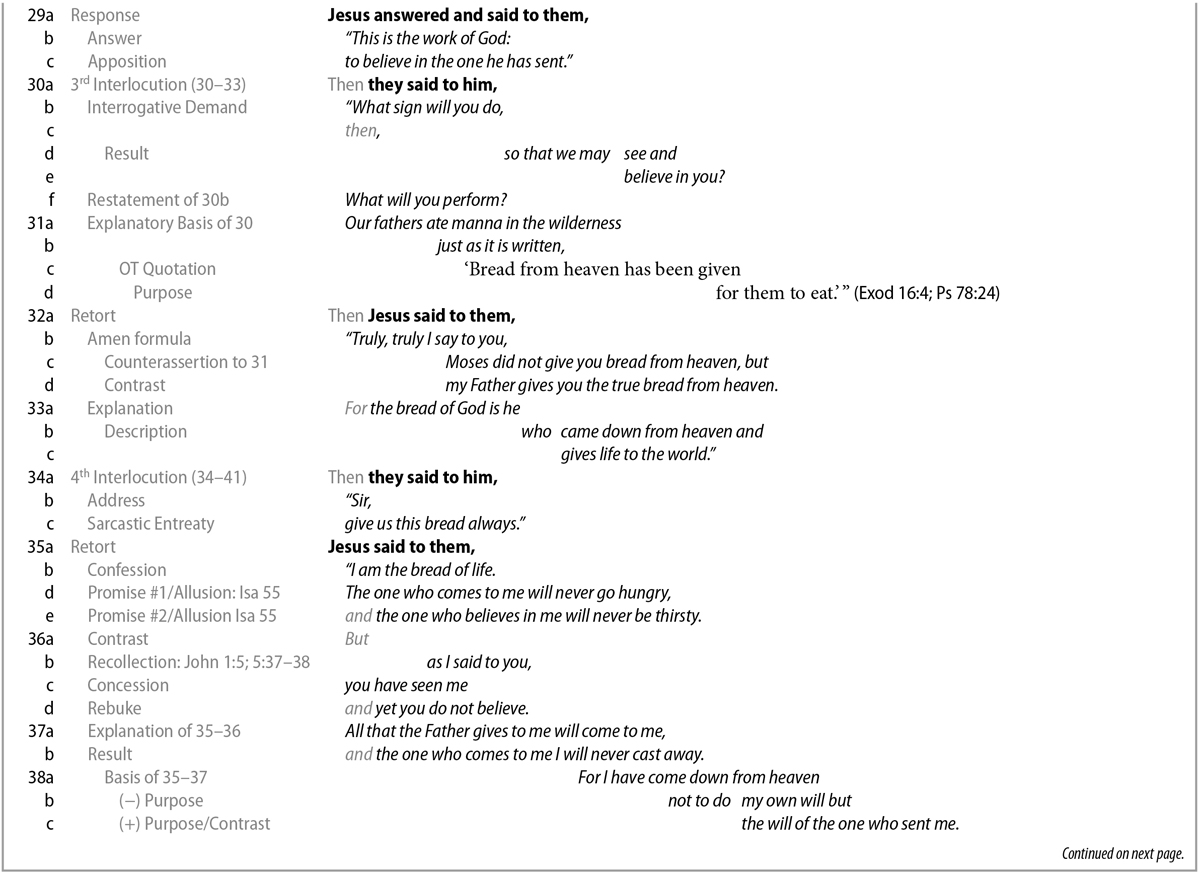

This is the third substantial dialogue in the narrative proper, and it is a social challenge dialogue, which takes the form of an informal debate intending to challenge the honor and authority of one’s interlocutor (see Introduction). Although a few interpreters define it technically as a dialogue, for the majority of interpreters this identification has little to no effect. Structural analyses deal almost exclusively with Jesus’s statements, almost certainly because the statements of Jesus are so important and hotly debated. But the dialogical structure into which those statements are placed by the narrative are also important and are strikingly similar to the dialogue with the Samaritan woman, with both having six verbal exchanges surrounded by a closing and opening scene. The dialogical form of this pericope needs to be given its due interpretive authority (see comments on v. 49).

Exegetical Outline

- E. The Bread of Life (6:22–71)

- 1. The Crowd Pursues Jesus (vv. 22–24)

- 2. First Verbal Exchange: “When Did You Come Here?” (vv. 25–27)

- 3. Second Verbal Exchange: The Work of God (vv. 28–29)

- 4. Third Verbal Exchange: God Gave You Bread, Not Moses (vv. 30–33)

- 5. Fourth Verbal Exchange: Jesus Is the Bread, Not Manna (vv. 34–40)

- 6. Fifth Verbal Exchange: “I Am the Living Bread” (vv. 41–51)

- 7. Sixth Verbal Exchange: Life in the Flesh and Blood of Jesus (vv. 52–59)

- 8. The Crowd Deserts Jesus (vv. 60–71)

- a. The Offense of Some “Disciples” (vv. 60–66)

- b. The Confession of the “Twelve” (vv. 67–71)

Explanation of the Text

We stated earlier that John 6 has been called “the Grand Central Station” of critical issues in John and a summary of numerous interpretive issues related to the Gospel as a whole (see comments before 6:1). One issue has been so frequently raised in regard to this pericope that we must address it briefly here: the institution of the Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist, or the “sacrament.”1

6:22 On the next day the crowd that had been with him on the other side of the sea saw that there was no other small boat there except one, and that Jesus had not entered into the boat with his disciples, but his disciples departed alone (Τῇ ἐπαύριον ὁ ὄχλος ὁ ἑστηκὼς πέραν τῆς θαλάσσης εἶδον ὅτι πλοιάριον ἄλλο οὐκ ἦν ἐκεῖ εἰ μὴ ἕν, καὶ ὅτι οὐ συνεισῆλθεν τοῖς μαθηταῖς αὐτοῦ ὁ Ἰησοῦς εἰς τὸ πλοῖον ἀλλὰ μόνοι οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ ἀπῆλθον). After what can be described as a sort of interlude (6:16–21), the narrative now returns to the crowd with whom chapter 6 began. The crowd that had completely misunderstood Jesus after the miraculous feeding (cf. 6:14–15) was now looking for him again, with intentions the reader is almost certainly supposed to assume are inappropriate. The phrase, “On the next day” (Τῇ ἐπαύριον), suggests that after Jesus’s escape from them, the following day they sought to find him again, likely to make him king (cf. 6:15). But instead of finding him, they discovered only the “small boat” (πλοιάριον), from which they concluded that Jesus had crossed the sea without a boat or his disciples. The confusing sense of the verse should not deter the reader from gathering the important details. The crowd is aware that Jesus departed and is convinced he did so separately and without a boat. The point of the narrator may simply be to confirm by means of the crowd the events told in the previous pericope (6:16–21).

6:23 But some boats came from Tiberias near the place where they had eaten the bread after the Lord had given thanks (ἄλλα ἦλθεν πλοῖα ἐκ Τιβεριάδος ἐγγὺς τοῦ τόπου ὅπου ἔφαγον τὸν ἄρτον [εὐχαριστήσαντος τοῦ κυρίου]). The narrator adds what appears to be isolated information to explain how the necessary transportation had arrived for a certain number of “the crowd” to continue their pursuit of Jesus (cf. v. 24). Several details are not provided by the narrator, suggesting that the reader is given a mere sketch of what really happened so as to make sense of where the narrative is going. As much as we have further questions for the narrator and other interests in the vague description of the events that transpired, we as readers must not get sidetracked from the narrative’s guiding intention.

6:24 When therefore the crowd saw that neither Jesus nor his disciples were there, they stepped into the boats and went to Capernaum for the purpose of seeking Jesus (ὅτε οὖν εἶδεν ὁ ὄχλος ὅτι Ἰησοῦς οὐκ ἔστιν ἐκεῖ οὐδὲ οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ, ἐνέβησαν αὐτοὶ εἰς τὰ πλοιάρια καὶ ἦλθον εἰς Καφαρναοὺμ ζητοῦντες τὸν Ἰησοῦν). The narrator concludes the crowds’ search for Jesus by describing how after not finding him or his disciples (and by implication being convinced that he had crossed the sea), they enter the boats themselves and pursue Jesus. The use of the purpose participial phrase, “for the purpose of seeking Jesus” (ζητοῦντες τὸν Ἰησοῦν), calls to mind the seeking (and finding) done by the first disciples (cf. 1:41, 45). The narrator has set up the dialogue to come, which is centered upon the crowd’s pursuit of Jesus and what they think he represents, which will be contrasted with the true identity of Jesus.

6:25 When they found him on the other side of the sea, they said to him, “Rabbi, when did you come here?” (καὶ εὑρόντες αὐτὸν πέραν τῆς θαλάσσης εἶπον αὐτῷ, Ῥαββί, πότε ὧδε γέγονας;). The first verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 25–27) begins when the crowd finds Jesus “on the other side of the sea” (πέραν τῆς θαλάσσης). The crowd addresses Jesus as “Rabbi” (Ῥαββί), which is reminiscent of Jesus’s first disciples revealing their interest in Jesus (cf. 1:38, 49). Although it serves as an honorific title that accorded the individual with the highest status as a teacher, it does not reveal the nature of their intended discipleship, which up to this point has been motivated more by hunger than humility (cf. 6:1–15).

6:26 Jesus answered to them and said, “Truly, truly, I say to you, you do not seek me because you saw signs but because you ate of the bread and had your stomachs filled” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, ζητεῖτέ με οὐχ ὅτι εἴδετε σημεῖα ἀλλ’ ὅτι ἐφάγετε ἐκ τῶν ἄρτων καὶ ἐχορτάσθητε). Jesus calls their spiritual bluff and directly addresses the source of the “seeking,” their stomachs, reflective of their selfish desires and passions.4 Although they “saw” (εἴδετε) signs, they did not comprehend them (cf. 2:11). The crowd wanted a king (cf. 6:15), one to take care of their physical needs, not the Prophet (cf. 6:14), who would condemn their sinfulness and announce the plan of God. The “signs” of Jesus according to the Gospel were pointing beyond themselves, past the earthly and physical to the heavenly and eternal. The signs challenge those who see them, for they are material testimony to the identity of Jesus. Thus, encountering one of Jesus’s signs can lead to a foreshortening of one’s sight, a lowering of one’s eyes from the true object of the sign to its mere symptoms (the miracle). Properly perceived, however, the signs draw one’s eyes directly to Jesus, deepening and strengthening belief in him. In this way, signs are truly gracious gifts to those who correctly see, and like curses of hindrance to those who do not.5

6:27 “Do not work for the food that perishes, but for the food that endures into eternal life, which the Son of Man will give to you. For on him the Father has placed his seal” (ἐργάζεσθε μὴ τὴν βρῶσιν τὴν ἀπολλυμένην ἀλλὰ τὴν βρῶσιν τὴν μένουσαν εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον, ἣν ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ὑμῖν δώσει· τοῦτον γὰρ ὁ πατὴρ ἐσφράγισεν ὁ θεός). What the crowd did not “see” or understand from the sign was the distinction between the temporary and the eternal, that is, the distinction between the Jesus they wanted and his true status as the Son of Man, sent from the Father. Rebuking the shallow “god of their stomachs,” Jesus provides the deep answer to their question, which they unknowingly asked as implied by the phrase, “When did you come here?” He states that they should not “work for” (ἐργάζεσθε) food that “perishes” (τὴν ἀπολλυμένην) but rather for the food “that endures into eternal life” (τὴν μένουσαν εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον). This food that endures into eternal life is equivalent to “a well of water springing up into eternal life” (4:14). This is what the crowd should pursue, and this is what Jesus alone can provide. The word “work” is not suggesting that we merit eternal life by works but is exhorting the crowd to apply themselves to the food that matters.

The verse goes on to declare that what is worked for is what the Son of Man “will give to you” (ὑμῖν δώσει). The antecedent of “which” (ἣν) is unclear. It could be referring to either “the food” or “eternal life.” The ambiguity only serves to highlight that both the food and the eternal life come directly from him in the form of a gift. As much as there is a strange paradox created between the command to “work” and the fact that what is obtained is ultimately “given” by Jesus, the two statements ultimately find agreement in Christ.6

Jesus offers confirmation of this when he declares that on him the Father “has placed his seal” (ἐσφράγισεν). The verb implies that Jesus has been marked with a seal as a means of identification, suggesting not only that the one sealed is endued with the authority of the one who sent him but also that the sender (the Father) is directly connected with the one sealed (the Son).7 In the ancient world, a seal was a mark of ownership. It is probably not referring to a particular act of sealing (e.g., the baptism in the Synoptics, or more likely for John, the descent of the Spirit in 1:33–34) but to the seal upon his whole person and activity. In this way, the first verbal exchange of the challenge dialogue ends, with Jesus, fully aware of what is in humanity (cf. 2:24–25), responding to their self-focused question with the truest answer he could give.

6:28 Then they said to him, “What must we do in order to perform the works of God?” (εἶπον οὖν πρὸς αὐτόν, Τί ποιῶμεν ἵνα ἐργαζώμεθα τὰ ἔργα τοῦ θεοῦ;). The second verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 28–29) focuses more directly on the challenge Jesus presents to the crowd’s misguided pursuits. The crowd responds to Jesus’s statement by asking for clarification and further explanation about how to do these “works.” The phrase “to perform the works of God” or “to work the works of God” (ἐργαζώμεθα τὰ ἔργα τοῦ θεοῦ) is emphatic in that both the verb and the direct object bear the sense of “work.” In spite of all the shocking things Jesus revealed—that he is the Son of Man, that the Father has placed his seal upon him, and that he can provide eternal life—it is surprising to see the focus land merely on the “works.” The reason is clear. They misunderstood Jesus’s rebuke regarding the inappropriate object of their work. Jesus is not inventing a new mode of work for his followers but is confronting the idolatrous object(s) of their current work.8 Their blindness in regard to self is being revealed by the dialogue. In the context of the dialogue, the crowd’s misguided focus on their duties and not Christ’s takes the form of a rhetorical grumbling, a cry of the victim who has been accused undeservedly. The Son of Man has just declared who he is and what he can do, and all they can think about (and see) is themselves and what they can do.

6:29 Jesus answered and said to them, “This is the work of God: to believe in the one he has sent” (ἀπεκρίθη ὁ Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Τοῦτό ἐστιν τὸ ἔργον τοῦ θεοῦ, ἵνα πιστεύητε εἰς ὃν ἀπέστειλεν ἐκεῖνος). Jesus responds to their question by changing their plural “the works of God” (τὰ ἔργα τοῦ θεοῦ) to “the work of God” (τὸ ἔργον τοῦ θεοῦ), about which he then provides the definitive answer: belief in Jesus. Jesus’s statement is in the form of a subjunctive with the conjunction often translated as “that/in order that” (ἵνα), which in this context is best taken as introducing an epexegetical clause explaining the preceding “this” (τοῦτό) and is fittingly translated as an infinitive.9 It is important to note that the verb “believe” (πιστεύητε) is in the present tense; believing in Jesus is less an act of faith and more a life of faith.10

The singular work of the Christian is faith in the Son who was sent from the Father. The Trinitarian nature of the Christian faith could not be more pervasive. Any work for God must involve faith in his Son. The Gospel has heralded this message since the prologue (see 1:18). The duties and responsibilities of humanity are entirely eclipsed by this one task of trusting in the person and work of the Son.11 It is likely for this reason that Jesus kept the word “work” alongside the call to faith in his response to the crowd’s question. There is a work to be done, but it belongs to God, both Father and Son (see comments on v. 44). Faith, then, is to trust in the work of God accomplished in Jesus Christ.

The separation of faith from works, fitting so nicely alongside Paul’s letter to the Romans, is not to deny a place for works. Rather, it is to place works beneath and subordinated to faith so that true “works” for Jesus may be deemed impossible outside of faith in Jesus. Belief in Jesus is the structural category into which all other works are placed and function.12 Even the value of a particular “work” is deemed worthy and acceptable only if it occurs by faith in Christ (cf. 5:28–29).13 In this way, faith becomes the only work of God for the Christian, for by it we possess the Son, obtaining the right to become children of the Father (1:12) and are therefore graciously governed by his Spirit. Only within this Trinitarian identity may the Christian be freed from the demands of God so as to properly respond to the commands of God. And this is what the crowd could not see by focusing entirely upon themselves. Ironically, their rhetorical grumbling in the form of a question was itself proof that they were “working” to an entirely different end.

6:30 Then they said to him, “What sign will you do, then, so that we may see and believe in you? What will you perform?” (εἶπον οὖν αὐτῷ, Τί οὖν ποιεῖς σὺ σημεῖον, ἵνα ἴδωμεν καὶ πιστεύσωμέν σοι; τί ἐργάζῃ;). In a third verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 30–33), the crowd presses Jesus to do the sign he mentioned in the first verbal exchange and the “work” he explained in the second verbal exchange. The crowd is pleading—note the emphatic “you” (σύ)—for a sign to confirm the things about which Jesus speaks, including his own person. Even their final question, asked in the form of a futuristic present, “What will you perform?” (τί ἐργάζῃ;), utilizes a verb that could also be translated as “work.” He claims to be the “Sent One”; they are now demanding that he match that claim with action—with a sign. Their questions are not symptoms of interest but the jabs of a challenge (cf. Mark 15:32).14 The social challenge is well underway.

6:31 “Our fathers ate manna in the wilderness just as it is written, ‘Bread from heaven has been given for them to eat’ ” (οἱ πατέρες ἡμῶν τὸ μάννα ἔφαγον ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ, καθώς ἐστιν γεγραμμένον, Ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ ἔδωκεν αὐτοῖς φαγεῖν). The challenge from the crowd is supported by biblical proof and the example of Moses. Their logic proceeded something like the following. If the God-ordained activity of Moses warranted a sign, certainly the prophet-like-Moses of Deuteronomy 18 would give an even greater sign. If this is the Prophet, giving not just perishing food but something “eternal,” he would prove himself to be the giver of even more and greater bread. The feeding of five thousand men can only have been the appetizer, signaling that the true meal was still to come. From this point on in the dialogue, the focus is markedly on the manna miracle and its motifs.15

It is important to note that the crowd uses biblical reasoning in their challenge to Jesus. Nowhere else in the Gospel do we find anyone but Jesus or the narrator/author quoting Scripture in this way. The biblical quotation is taken from both Exodus 16 and Psalm 78. The emphasis of the crowd seems to be primarily on the phrase, “from heaven” (cf. Ps 78:24), which is why the feeding of the five thousand men seems to be an unsatisfactory sign for them. Bread “from heaven” has a strong biblical heritage (cf. Ps 105:40; Neh 9:15), and Jewish literature suggests that Jews believed there would be an end-time recurrence of God’s provision of bread from heaven.16 Jesus had fed them “from below”; in their opinion, it was time for him to make good on his confession and feed them “from above,” as Moses had done and promised would happen.

6:32 Then Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly I say to you, Moses did not give you bread from heaven, but my Father gives you the true bread from heaven” (εἶπεν οὖν αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, οὐ Μωϋσῆς δέδωκεν ὑμῖν τὸν ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ, ἀλλ’ ὁ πατήρ μου δίδωσιν ὑμῖν τὸν ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ τὸν ἀληθινόν). Beginning his statement with his authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51), Jesus counters their biblical reasoning and reconstructed tradition of the promise of God. He rejects outright that Moses actually gave bread “from heaven”—a remarkable negation (challenge!) of what would have been a saturated biblical logic. It is not Moses who gave bread to them, “but my Father” (ἀλλ’ ὁ πατήρ μου). This rebuttal of the crowd’s claim of tradition demands that the true agent of manna was never Moses but the God of Moses. In sharp contrast to the rabbinic argument that Moses was the “first redeemer,” and the assumption that followed that the Prophet would be the “second redeemer” (cf. 2 Bar. 29:8), Jesus declares that there had always been only one redeemer, and it was not Moses. This is a hermeneutical correction to the crowd’s reading of Scripture.

Alongside this correction is another, more theological correction: it was not Moses but the Father who gives them “the true bread from heaven” (τὸν ἄρτον ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ τὸν ἀληθινόν). Just as Moses was seen in place of God, the true giver, so also the substance of bread (manna) was seen in place of the “true bread” (which will be explained in v. 33). This is an even more remarkable correction, for it is one thing to correct the crowd when they assert Moses as the giver, thus allowing God (inappropriately) to become merely implicit and therefore secondary. But it is quite another for Jesus to claim that the physical bread was also falsely asserted as the primary bread. There is no need to try to explain this exegetical maneuver based upon Jewish exegesis or typology, even if traits of such maneuvers are present,17 just as no solution could be offered to explain Jesus’s correction of the temple to the Jewish authorities in 2:12–25. This time, however, there is no interpretive assistance provided by the narrator (cf. 2:21–22).

Beyond the insight already provided by the prologue and the developing narrative, the only possible clue is in the present-tense verb “gives” (δίδωσιν). It can quite easily be taken as a historic present and thus be referring to the bread that God gave through Moses. But why the present tense when the aorist, for example, would be more effective? The answer must be that Jesus spoke in the present intentionally so as to communicate about a “giving” in the present. In this way, the sense would be something like this: “But my Father is giving you at this moment the true bread from heaven.”18 Although our translation cannot maintain both senses, the reader is to hear the echoes from them both in Jesus’s words. For this reason these words of Jesus—this remarkable declaration—is not merely a rebuke but is also the manifestation of the long-awaited promise of God’s provision.

6:33 “For the bread of God is he who came down from heaven and gives life to the world” (ὁ γὰρ ἄρτος τοῦ θεοῦ ἐστιν ὁ καταβαίνων ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καὶ ζωὴν διδοὺς τῷ κόσμῳ). Jesus then declares that he is the true bread: “For the bread of God is he” (ὁ γὰρ ἄρτος τοῦ θεοῦ ἐστιν). The opening phrase could be taken attributively (“This is the bread of God that . . .”), but while grammatically possible the context presses us to take the phrase predicatively (“He is the bread of God . . .”). The personalization of the bread is not only accurate but rhetorically powerful, fitting the forthcoming dialogue (cf. vv. 53–58).

If there was any doubt about the present status of “gave” in v. 32, it has now been answered. The “bread of God” is the more precise, more direct way of referring to the “bread of heaven”; it is not a different thing. Jesus is and has always been the bread that God would give to his people, the long-awaited promise now being fulfilled. This bread has arrived in a similar manner to the bread already eaten by the Israelites, but there are several important differences. First, like the manna this bread also “came down from heaven” (ὁ καταβαίνων ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ), but in a manner unique from what the Israelites received. The Israelites had to wait each day for a fresh arrival of bread, whereas this bread has already come down. Second, while the manna was given to sustain life, so also this bread “gives life to the world” (ζωὴν διδοὺς τῷ κόσμῳ). But the “life” this bread gives is life par excellence (see comments on 1:4 and 3:15), and the recipient is no longer Israel alone but the entire “world” (cf. 4:42). In this third verbal exchange of this dialogue, Jesus has declared that “my Father” is the true provider, that he is the true bread, and that “life” itself, not the mere satiation of hunger, is the true provision.

6:34 Then they said to him, “Sir, give us this bread always” (Εἶπον οὖν πρὸς αὐτόν, Κύριε, πάντοτε δὸς ἡμῖν τὸν ἄρτον τοῦτον.). The fourth verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 34–40) centers more directly around this bread of God. The ambiguity of Jesus’s words mixed with their distorted perception of God directed the crowd to bread and not the bread. The crowd, like the world, has become so accustomed to that which is perishing that they are unable to make sense of that which is eternal (cf. v. 27).

After taking into account the rebuke Jesus gave the crowd in the third verbal exchange, the crowd’s address to Jesus, “Sir” (Κύριε), though dressed in a respectful form, is anything but polite. Under a cloak of polite expression, the crowd speaks to Jesus with sarcastic daggers in a manner similar to Nicodemus (see comments on 3:2) and thus moves the social challenge forward.19 Their language, “this bread” (τὸν ἄρτον τοῦτον), also betrays their intentions. They realize Jesus is speaking beyond the manna of Moses, so they beckon him—challenge him—to produce it. Even the grammar suggests a mockery is in play with the strange combination of the aorist imperative, “give” (δὸς), which deemphasizes duration and repetition, and the adverb, “always” (πάντοτε), which is clearly durative. They had asked him for a general sign in the previous verbal exchange (v. 30), which he was able to deflect by his rebuke. How could he now avoid “proving” himself to them after making such cavalier statements?

6:35 Jesus said to them, “I am the bread of life. The one who comes to me will never go hungry, and the one who believes in me will never be thirsty” (εἶπεν αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος τῆς ζωῆς· ὁ ἐρχόμενος πρός με οὐ μὴ πεινάσῃ, καὶ ὁ πιστεύων εἰς ἐμὲ οὐ μὴ διψήσει πώποτε). Jesus’s response to the crowd’s cloaked retort is one of the most famous declarations of our Lord in the Gospel, even in the entire canon. Almost no explanation is needed in regard to the confession, “I am the bread of life” (Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος τῆς ζωῆς), for the entire dialogue has provided the needed background and foreground of the title. Jesus is—and has always been—the true bread. Moses did not and could not give this bread, nor did he or this crowd even consider the “enduring bread of eternal life” that was to come and is now here (cf. v. 27). The crowd mockingly asks Jesus for this “magical” bread that trumps the famous bread of Moses, and Jesus offers himself. What was insightfully implied in v. 33 has now been shouted in explicitness.

The true disciple of the bread of life is the one who “comes” (ὁ ἐρχόμενος) and “believes” (ὁ πιστεύων), with the latter term serving as an insightful commentary on the former. To come to Jesus is to believe in him, and both of these are defined by the motif of eating that drenches this entire dialogue. For this reason Jesus can claim that the disciple who comes to/believes in him will no longer “go hungry” (πεινάσῃ) or “be thirsty” (διψήσει), for they have fully embraced Christ as the source and sustenance of life. The motif of thirst recalls Jesus’s dialogue with the Samaritan woman (see 4:14). By combining hunger and thirst in the metaphor of the bread of life, Jesus embodies in his person all promises of satisfaction and satiation. Jesus is the recipe for the soul. While it is clear that the remainder of the dialogue will explicate further this confession, it is also clear that the Gospel as a whole (and all Scripture) is part of the necessary interpretive matrix into which this confession is fit (e.g., Isa 55:1–3, 6–7, 10).

“I am the bread of life” is the first of seven formal “I am” statements in the Gospel, each containing “I am” (Ἐγώ εἰμι) and a predicate. The “bread of life” predicate serves to convey the absolute necessity of Christ by linking the most basic and foundational needs of human life to his person and work.20 In a manner not yet fully described, the phrase signifies that in Jesus there is an eternal sufficiency in which there is no want.21 In Jesus there is an “eating” that provides deep rest for one’s whole being, “even if all about me should go to pieces.”22

6:36 “But as I said to you, you have seen me and yet you do not believe” (ἀλλ’ εἶπον ὑμῖν ὅτι καὶ ἑωράκατέ [με] καὶ οὐ πιστεύετε). The grand offer of Christ is immediately and strongly contrasted with what Jesus reveals about the unreceptive crowd. His claim to have already communicated this is not necessarily suggesting it occurred earlier in this dialogue (e.g., in v. 26) but in words spoken to other disbelievers (possibly 5:37–38), representing the innate disbelief of a world in darkness (1:5). Jesus decries that although they “have seen” (ἑωράκατέ) him, made emphatic with the perfect tense, they still do not believe. Their disbelief is highlighted by the contrastive conjunction “and yet” (καὶ . . . καὶ),25 which implicitly offers judgment on the crowd. This crowd has seen and heard God in the flesh, and yet the encounter has aroused not their faith but their curiosity, physical appetites, and political ambitions.26 Even worse, they have given challenge to the very God for whom they claim to be looking.

6:37 “All that the Father gives to me will come to me, and the one who comes to me I will never cast away” (Πᾶν ὃ δίδωσίν μοι ὁ πατὴρ πρὸς ἐμὲ ἥξει, καὶ τὸν ἐρχόμενον πρὸς ἐμὲ οὐ μὴ ἐκβάλω ἔξω). In order that the crowd’s disbelief not be viewed as their own possession, Jesus offers a counter by placing their disbelief fully within the sovereign domain of God. That is, rather than rejecting God, in a real way God had already rejected them. “All” (Πᾶν) is neuter and singular and thus is referring not to individuals but to “a general quality” of persons.27 In this context, the quality is not their own but that which only the Father can give. The second part of the verse, which seems to emphasize more the individual’s responsibility, is not contradicting the first part. The Son is not welcoming beyond what the Father is giving, but is matching in detail—note the move from collective to individual, “the one who comes” (τὸν ἐρχόμενον)—a responsiveness coordinated with the Father’s. Even more, the statement, “I will never cast away” (οὐ μὴ ἐκβάλω ἔξω), strengthened by the emphatically negated subjunctive, declares that those the Father brings in the Son will keep in.28 The final three verses of this verbal exchange will explain the nature of this coordination between the Father and the Son (vv. 38–40).

6:38 “For I have come down from heaven not to do my own will but the will of the one who sent me” (ὅτι καταβέβηκα ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ οὐχ ἵνα ποιῶ τὸ θέλημα τὸ ἐμὸν ἀλλὰ τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πέμψαντός με). The reason for the Son’s coordinated effort with the work of the Father is because his entire mission is defined by the Father. The Son who “came down from heaven” (καταβέβηκα ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ) is performing the tasks given to him by “the one who sent me” (τοῦ πέμψαντός με). The “coming” of Jesus is rooted in and a subset of the “sending” by the Father. For this reason the Son claims to do “not my own will but the will” (τὸ θέλημα τὸ ἐμὸν ἀλλὰ τὸ θέλημα) of his Father. There can be no severing the Father from the Son. Jesus is not merely describing the ontological and functional unity between himself and his Father but is also rebuking the crowd for even considering to pit the provision of God for his people against the provision provided through the Son. Even the presence of the Son, which is strengthened by the perfect tense, “I have come down” (καταβέβηκα), gives force to Jesus’s location on earth and, therefore, further warrant for its direct connection to the mission “from heaven” (ἀπὸ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ).29

6:39 “And this is the will of the one who sent me, that I might not lose any out of all that he has given to me but will raise them on the last day” (τοῦτο δέ ἐστιν τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πέμψαντός με, ἵνα πᾶν ὃ δέδωκέν μοι μὴ ἀπολέσω ἐξ αὐτοῦ ἀλλὰ ἀναστήσω αὐτὸ [ἐν] τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ). Jesus continues to explain the coalescence of the Father and Son with a formal description. “This is the will of the one who sent me” (τοῦτο δέ ἐστιν τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πέμψαντός με) contains a substantival participle that is functioning as a subjective genitive, which could also be translated, “This is what the one who sent me wills.”30 The will for the Son is that “I might not lose any out of all that he has given to me” (πᾶν ὃ δέδωκέν μοι μὴ ἀπολέσω ἐξ αὐτοῦ). This verse provides further insight into Jesus’s earlier statement that he “will never cast away” (v. 37). Just as it is within the will of God that some be given to the Son, so also it is within the will of God that the Son not lose those he has received (cf. 6:12).

Rather than losing them, it is the will of the Father that the Son “will raise them on the last day” (ἀναστήσω αὐτὸ [ἐν] τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ). We have already been told that a future day (or “hour”) is coming for which Jesus is the assigned agent of the resurrection of life and judgment (5:28–29). The expression here is further confirmation that the Gospel is familiar with a futuristic eschatology. Even more, it demands that the bread of life is not merely ephemeral but is solid food that is connected to an ultimate and final reality.31 The metaphorical language previously used is merely the sign used to depict a true substance, the present and future reality centered upon Christ.

6:40 “For this is the will of my Father, that all who see the Son and believe in him will have eternal life, and I myself will raise him on the last day” (τοῦτο γάρ ἐστιν τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πατρός μου, ἵνα πᾶς ὁ θεωρῶν τὸν υἱὸν καὶ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν ἔχῃ ζωὴν αἰώνιον, καὶ ἀναστήσω αὐτὸν ἐγὼ [ἐν] τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ). The fourth verbal exchange concludes with Jesus giving his final explanatory comments. The “one who sent me” (vv. 38–39) is now explicitly stated as “my Father” (τοῦ πατρός μου). And those “given” by the Father and kept secure by the Son are those “who see the Son and believe in him” (ὁ θεωρῶν τὸν υἱὸν καὶ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν). The inclusion of “seeing” suggests that the one who believes has the vision to recognize who the Son is—God’s agent and representative. The crowd saw signs which Jesus performed but could not really see him (cf. v. 26). But he will be seen, if not now, at the “hour” of the eschaton, when as he promises with an emphatic first-person pronoun, “I myself will raise him” (ἀναστήσω αὐτὸν ἐγὼ). Jesus concludes the fourth verbal exchange of the dialogue with a rebuke. It is centered upon his identity as the Son who functions entirely within the will of his Father from first (“the beginning”; 1:1) to last (“on the last day”; 6:40).

6:41 The Jews were grumbling about him because he said, “I am the bread that has come down from heaven” (Ἐγόγγυζον οὖν οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι περὶ αὐτοῦ ὅτι εἶπεν, Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος ὁ καταβὰς ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ). The fifth verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 41–51) moves the social challenge in a slightly different direction, for the crowd begins to reveal (at least among themselves) their utter rejection of the claims made by Jesus and therefore of Jesus himself (v. 42). Without being given any recourse to their reasoning, the Jews are clearly opposed to the claims Jesus has made, probably not only in regard to himself but also in regard to the claims he made for God (his Father).

An interesting change also occurs in the narrator’s title for the character that had been called “the crowd” (ὁ ὄχλος). For the first time in this pericope—almost out of nowhere—the narrator calls Jesus’s interlocutors “the Jews” (οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι) and will maintain this title throughout the rest of the dialogue (cf. v. 52). There is no evidence of a change of scene or historical situation; in fact, quite the contrary, the dialogue attends to details and issues rooted in its earlier parts. The change in description must be viewed as having a literary (and rhetorical) function for the narrator. The Gospel frequently uses the title “the Jews” for leaders or spokespersons who are hostile to Jesus (see comments on 1:19), very much fitting the tenor of this social challenge. But what is its specific nuance here?

A visible clue can be derived from the narrator’s choice of words regarding the reaction of “the Jews” to Jesus’s claims. According to the narrator, the Jews were “grumbling” (Ἐγόγγυζον), a term which depicts a manner of expression done “in low tones of disapprobation,” that is, disapproval or condemnation.32 The term has a significant past, particularly in regard to the Israelites—the Jews—who exhibited their unbelief by “grumbling” against Moses and Aaron, their representatives before God (Exod 16:2). The Jews, like their forefathers, were rejecting God’s agent and therefore were rejecting God himself. As Hoskyns describes it, by their grumbling “they preserve the genuine succession of unbelief.”33

6:42 And they said, “Is this not Jesus, the son of Joseph, whose father and mother we know? How can he now say, ‘I have come down from heaven?’ ” (καὶ ἔλεγον, Οὐχ οὗτός ἐστιν Ἰησοῦς ὁ υἱὸς Ἰωσήφ, οὗ ἡμεῖς οἴδαμεν τὸν πατέρα καὶ τὴν μητέρα; πῶς νῦν λέγει ὅτι Ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβέβηκα;). The message of Jesus was so shocking that the “Jews” begin to deduce from what they assumed about Jesus in order to evaluate his statements against his person. He speaks like he has just come down from heaven, denoted by the inclusion of “now” (νῦν), which is to be contrasted with the properly basic knowledge that he came from the home and lineage of a known and earthly family, as the son of Joseph. Jesus’s words are so evidently claiming a divine heritage that the crowd asks what is clearly a rhetorical question since they already know his father and mother. They do so in order to rebuke his visionary statements and theophanic self-descriptions. The question is loaded with irony for the reader, who knows the true Father of Jesus (cf. 1:1–2, 14, 18).

6:43 Jesus answered and said to them, “Stop grumbling among yourselves” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Μὴ γογγύζετε μετ’ ἀλλήλων). Even though the Jews were not speaking to him but among themselves, Jesus silences their grumbling. This is a unique moment in the dialogue where Jesus responds to what they said among themselves, not to him. As Moses declared to the grumbling Jews in the wilderness, “[the LORD] has heard your grumbling. . . . You are not grumbling against us, but against the LORD” (Exod 16:7–8), so also Jesus “hears” the grumblings of the Jews. This time, however, God, not Moses, confronts the grumbling Jews directly.

6:44 “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him, and I will raise him on the last day” (οὐδεὶς δύναται ἐλθεῖν πρός με ἐὰν μὴ ὁ πατὴρ ὁ πέμψας με ἑλκύσῃ αὐτόν, κἀγὼ ἀναστήσω αὐτὸν ἐν τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ). Jesus begins to rebuke the Jews, clarifying further exactly who he is. Moses only told the Jews in the wilderness that God heard their grumbling (Exod 16:7); Jesus declares what the Father was thinking about it. This verse is commonly used as a prooftext in debates regarding election, and in many ways rightly so. We would be wrong, however, to miss this as a further rebuke of the Jews, not only of the forefathers but also their contemporaries.

Even more explicitly than vv. 37–40, where Jesus makes connection between the will and giving of the Father to those who believe, Jesus declares that “no one can come to me unless the Father . . . draws him” (οὐδεὶς δύναται ἐλθεῖν πρός με ἐὰν μὴ ὁ πατὴρ ἑλκύσῃ αὐτόν). The key verb, “draw” (ἑλκύσῃ), implies that “the object being moved is incapable of propelling itself or in the case of persons is unwilling to do so voluntarily.”34 While theologians will often posit that such a drawing can be resisted, there is not one example in the NT of the use of this verb where the resistance is successful.35 The statement plainly depicts the inability of a person to “come” (ἐλθεῖν) to Jesus “unless” (ἐὰν μὴ) the Father directly acts in an intervening manner. God is the only acting agent. Such language is stark and even offensive, certainly to the Jews at the time and to a large amount of readers of the Gospel today. Yet it cannot be explained away. Without any real argument, Jesus presents God as the primary agent of salvation, just as he had already made clear that the Father is the one who enacts belief as part of his gift and will (vv. 37–40). In this way, Jesus offers a preemptive strike against any and all arguments presented by the Jews. They came as followers (cf. vv. 22–24) but have now been challenged to rethink the object of their allegiance (cf. v. 26).

6:45 “It is written in the prophets, ‘They will all be taught by God.’ All who heard and learned from the Father come to me” (ἔστιν γεγραμμένον ἐν τοῖς προφήταις, Καὶ ἔσονται πάντες διδακτοὶ θεοῦ· πᾶς ὁ ἀκούσας παρὰ τοῦ πατρὸς καὶ μαθὼν ἔρχεται πρὸς ἐμέ). Jesus gives further explanation to his comment in v. 44, this time with the help of the Old Testament. Claiming to speak from the “prophets” (plural), Jesus quotes from Isaiah 54:13: “All your children will be taught by the LORD, and great will be their peace.” This prooftext serves to make clear that if one comes to Jesus, one has “heard” (ἀκούσας) and “learned” (μαθὼν) from the Father. These two terms are best viewed as synonyms. What cannot be missed is the necessary connection between the teaching from the Father and the coming to Jesus. This connection and the use of Isaiah make three important claims.

First, as an explanation of what he previously said (v. 44), Jesus makes clear that the intention had always been that God would be the primary agent of belief. It is not only God who propels a person toward Christ (v. 44), but also God who provides the primary instruction. Belief in Christ is enacted by the agency of God who “draws” and “teaches” his children, ultimately being made known personally through Jesus Christ (cf. v. 46). As Augustine explains, “The Son spoke, but the Father taught.”36

Second, by using this prophecy Jesus is declaring that this reality is being fulfilled in his person. Jesus is “the teaching God,” instructing his people directly. There is no longer an intermediary, such as Moses, Aaron, or any kind of priest, for the Word of instruction has arrived. To reject Christ, as the Jews were doing, is proof that the teaching one upholds has not been given by God. Anything that is actively opposed to Christ or passively void of Christ is by definition not instruction from God. The reader is exhorted to be Christ centered, since this is the only subject matter God teaches his children.

Third, this statement serves as a first-order rebuke of the Jews, who reject the teaching of the one they claim to be hoping for (cf. 6:14); yet it also serves to locate them outside the people of God since they do not take part in what was promised to God’s “children.” Although Jesus does not include the second half of Isaiah 54:13, “and great will be [your children’s] peace,” in the context of the dialogue and the earlier connection to the Jews’ forefathers, the implication is strong. These children have not yet found peace, for instead of seeking the satisfaction of their souls, they are pleased merely to satisfy their stomachs (vv. 26–27).

6:46 “Not that any person has seen God except the one who is from God, he has seen the Father” (οὐχ ὅτι τὸν πατέρα ἑώρακέν τις εἰ μὴ ὁ ὢν παρὰ τοῦ θεοῦ, οὗτος ἑώρακεν τὸν πατέρα). Jesus explains further our second point from v. 45 that he is the fulfillment of the presence of the “teaching God.” Some have suggested that this verse is a parenthetical intrusion by the narrator; however, not only is there no such change of speaker signaled to the reader, but when viewed from Jesus’s own lips the statement is profound. By beginning with a negation, Jesus is clarifying any possible misunderstanding regarding the teaching presence of God. The teaching of God is not in isolation from his Son, that is, some kind of mystical, direct revelation from God to an individual person, but is centered upon and mediated through him. Jesus is the teaching presence of God, the living narration of God, the ultimate spokesperson for God. The warrant for this claim is that he is the only one who is “from God” (παρὰ τοῦ θεοῦ) and “has seen the Father” (ἑώρακεν τὸν πατέρα), which was first declared to the reader in the prologue (1:18). There is no hearing, learning, or seeing other than through Jesus Christ. The Jews’ rejection of Christ in favor of “God” is a non sequitur, for to reject Christ is to reject God.

6:47 “Truly, truly I say to you, the one who believes has eternal life” (ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, ὁ πιστεύων ἔχει ζωὴν αἰώνιον). Jesus now states more firmly a confession about himself that in the logical flow of the last few verses is rooted in the Trinitarian identity of God. By beginning with the authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51), Jesus is speaking as God and on God’s behalf. Jesus brings his discussion of God and belief full circle by concluding that this belief produces eternal life. In a movement from eternal God to eternal life, the person who believes in Christ is already receiving everything that has been announced: hearing, learning, and seeing the Father through Christ. Believing is now referred to absolutely, with no mention of “in me” or “in God” by Jesus.37 The reason is because one cannot make such distinctions. Belief in God is belief in the one he sent, Jesus Christ, and belief in Christ is belief in God. If it is real belief, both God and Christ are being believed. Such a statement silences the earlier request of the crowd for a sign so that they might believe (v. 30). The very question revealed the answer and serves to explain why Jesus turned their seeking on its head and initiated his challenge.

6:48 “I am the bread of life” (ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος τῆς ζωῆς). The fifth verbal exchange has moved so powerfully from Jesus to God and back to Jesus that with simplicity and rhetorical precision Jesus restates his claim as the bread of life (see comments on v. 35). This title of Jesus provides the theme of the entire dialogue, and after several necessary and combative verbal exchanges, Jesus declares it again to press further the significance of his person and work.

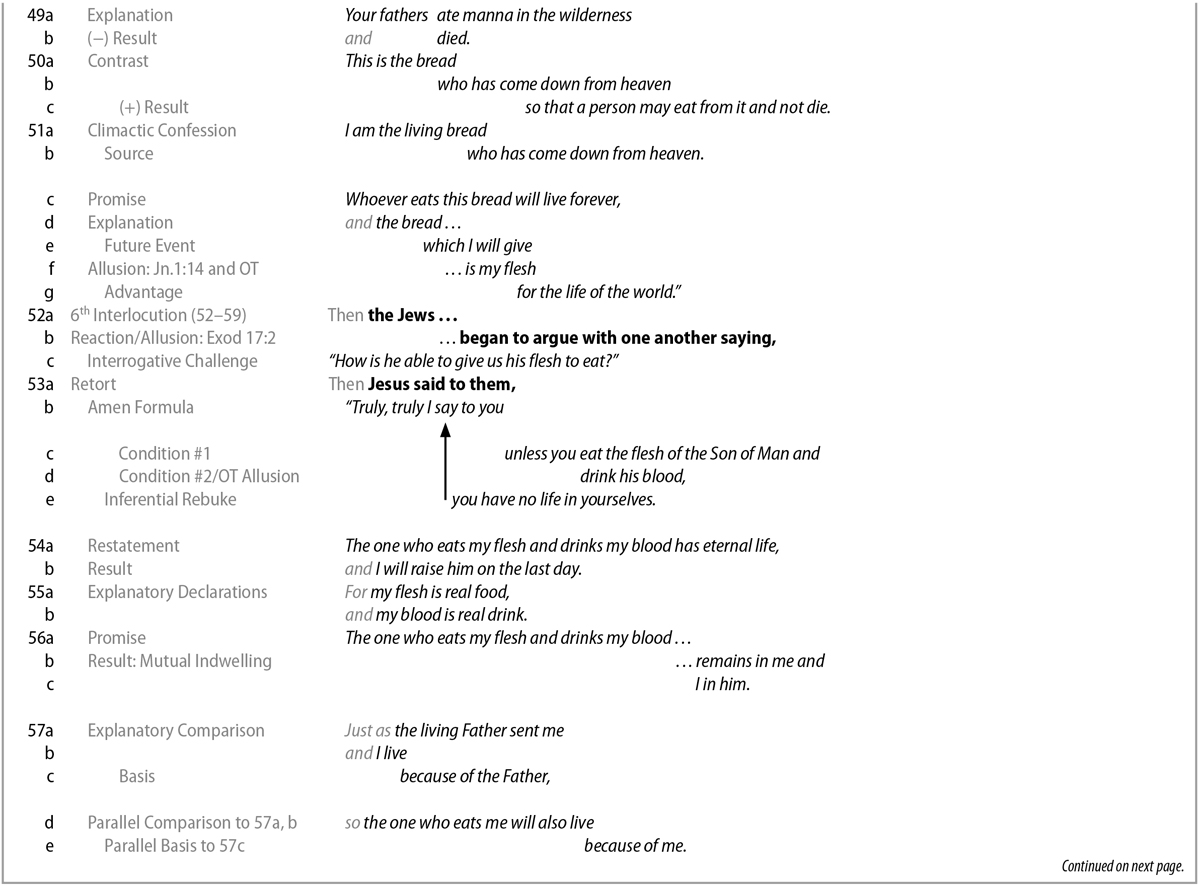

6:49 “Your fathers ate manna in the wilderness and died” (οἱ πατέρες ὑμῶν ἔφαγον ἐν τῇ ἐρήμῳ τὸ μάννα καὶ ἀπέθανον). Following his restated claim, Jesus provides a three-verse summary (vv. 49–51) that serves to conclude the fifth verbal exchange. It is unfortunate that many commentators project a section break after v. 48.38 It is here where the awareness of the dialogue guides the reader to see the structure of the pericope. These last three verses are essential commentary to the restated claim of Jesus and speak directly into the message Jesus has been presenting against the Jews. Jesus is still responding to their grumbling “origin” question of vv. 41–42, with his response giving engaged attention and making direct allusion to the issues raised in those verses. Not until v. 52 will the dialogue adjust its focus.

The earlier conflict between Jesus the bread and the bread of Moses is now readdressed with new insights, for Jesus’s claim to be “the bread of life” is now unavoidably linked to the divine provision and agency of God himself. Jesus is the offering of God, the provision for his people, the bread, and this has always been the case—both for the forefathers in the wilderness and their contemporaries, the crowd/Jews. What Jesus declares in vv. 48–51 is essential to what he will declare in the final verbal exchange. It is he whom God has always given to his people, and he is the bread that needs to be eaten. The proof of this was made manifest at the time of the forefathers. They “ate manna” (ἔφαγον τὸ μάννα) and still “died” (ἀπέθανον). The logic is that bread was not truly life sustaining, otherwise the forefathers would not have died. Their death certifies that manna was insufficient and that it was not the final offering of bread from heaven.

6:50 “This is the bread who has come down from heaven so that a person may eat from it and not die” (οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ἄρτος ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβαίνων ἵνα τις ἐξ αὐτοῦ φάγῃ καὶ μὴ ἀποθάνῃ). The final offering of bread, the one competent to bestow true life, is Jesus himself. In contrast to the manna, “This is the bread” (οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ἄρτος) from which “you may eat and not die” (φάγῃ καὶ μὴ ἀποθάνῃ). The subjunctives denote the possibility of life offered in the bread and the possibility offered to the “person” (τις) who partakes. In line with v. 49, death is now depicted as surmountable. The words Jesus used earlier, “believe” and “come to me” (vv. 35, 37, 44, 47), are now fully contained in the imagery of “eating,” just as who he is and what he offers is now contained in the imagery of “bread.” This demands that we interpret this imagery as flowing from the semantics of the preceding dialogue and not by a later, sacramental context.39 But it also suggests that “eating” is not intended to swallow the semantic meaning of “believe” and “come” but to contribute to our understanding of what the terms actually entail.40

6:51 “I am the living bread who has come down from heaven. Whoever eats this bread will live forever, and the bread which I will give is my flesh for the life of the world” (ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος ὁ ζῶν ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβάς· ἐάν τις φάγῃ ἐκ τούτου τοῦ ἄρτου ζήσει εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα· καὶ ὁ ἄρτος δὲ ὃν ἐγὼ δώσω ἡ σάρξ μού ἐστιν ὑπὲρ τῆς τοῦ κόσμου ζωῆς). After speaking of “the bread” in the third person, he now speaks of it in the first person: “I am the living bread” (ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος ὁ ζῶν). But instead of his previous confession, “the bread of life,” he now says in a synonymous manner that he is “the living bread,” a nuance that reflects the presence and permanence of the “life” that he now offers and eternally is. The manna-bread that came down has been replaced and fulfilled by the man-bread who has also come down.

This “living bread” is given so that a person may “eat” (φάγῃ). As much as this imagery is still alluding to the manna in the wilderness, it is also referring to something just as edible and presently available through Jesus Christ—for only he can give eternal life. More shocking is the final statement, that “the bread which I give is my flesh” (ὁ ἄρτος δὲ ὃν ἐγὼ δώσω ἡ σάρξ μού ἐστιν). The dialogue has been moving in this direction since the beginning of chapter 6. The feeding, the manna, the eating, the bread, which is now revealed to be “my flesh,” is the exact depiction provided in the prologue of the fleshly body of Jesus (1:14). Since “flesh” is conceptually linked to sacrifice—the cross (see comments on 1:14)—its use here explains the nature of God’s provision through Jesus.

Such a statement has easily surpassed the manna of the Jews, but it must not be limited by the Eucharist (the Lord’s Supper).41 Both “breads” are representative of the bread. They are signs that signify something beyond themselves, pointing outward from their position in salvation history. The Gospel has been working to explain the theological, metaphysical, and religious significance of Jesus’s “flesh”—as the man (embracing humanity and the world; cf. 1:14), as the temple (mediating between God and the world; cf. 2:12–25), and now as the living bread (conquering death and offering life in his person). The feeding of the large crowd was just the starter, for the meal Jesus offers is for “the world” (τοῦ κόσμου). This is all part of the will of God, the drawing of his people, motivated by his love for the world (3:16). With this robust declaration, the fifth verbal exchange concludes.

6:52 Then the Jews began to argue with one another saying, “How is he able to give us his flesh to eat?” (Ἐμάχοντο οὖν πρὸς ἀλλήλους οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι λέγοντες, Πῶς δύναται οὗτος ἡμῖν δοῦναι τὴν σάρκα [αὐτοῦ] φαγεῖν;). The sixth and final verbal exchange of the dialogue (vv. 52–59), carrying the force of the preceding verbal exchanges, gives a final depiction of the shocking statement made by Jesus in v. 51. The dialogue has offered a true challenge to the Jews, who are depicted by the narrator as initiating an argument among themselves. The ingressive imperfect, “began to argue” (Ἐμάχοντο), is a strong term that depicts a heated dispute. The arguing, however, is not taking place between the Jews as if they are debating the issue among themselves with a mixture of opinions for or against but is to be viewed as an intensification of the “grumbling” of v. 41. The uniformity of their collective question confirms their agreement to the contrary. Like their forefathers, who not only “grumbled” (Exod 16:2) but also “argued with Moses” so as to put God to the test (Exod 17:2), these Jews argue and test Jesus.42 Their question is a final challenge in the form of a mocking rebuke and is rooted in their unbelief. Ironically, however, their question is actually important and provides Jesus with a final explanation about eating his flesh, the living bread.

6:53 Then Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly I say to you unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in yourselves” (εἶπεν οὖν αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, ἐὰν μὴ φάγητε τὴν σάρκα τοῦ υἱοῦ τοῦ ἀνθρώπου καὶ πίητε αὐτοῦ τὸ αἷμα, οὐκ ἔχετε ζωὴν ἐν ἑαυτοῖς). Without any retraction or nuance, and introduced with his authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51), Jesus reiterates his earlier statement (v. 51) in a more robust manner. Jesus states even more explicitly that it is his flesh that is to be eaten, including this time the insight that it is the flesh “of the Son of Man” (cf. v. 27), thus combining in his person the baseness of the flesh of humanity with the loftiness of the Son of Man (see comments on 1:51).

Even more than eating, Jesus adds a further, participatory requirement that they must “drink his blood” (πίητε αὐτοῦ τὸ αἷμα). If eating flesh was shocking, drinking blood was outright offensive and especially abhorrent to Jews who were explicitly forbidden to partake of blood (cf. Gen 9:4).43 Jesus had become more than a mystery to the Jews; he was now unavoidably scandalous. While several suggest that “blood” is suggestive of life, since the two concepts are associated in parts of the OT (e.g., Lev 17:11, 14; Deut 12:23), the biblical evidence as a whole clearly suggests that “blood” is conceptually related to and reflective of “death.”44 In combination with “flesh” and in light of the preceding verbal exchange in which sacrifice and the cross were implied, the language here is intentionally directed toward the sacrificial death of Christ. In some manner, then, the benefits of the cross of Christ are received by means of eating and drinking the flesh and blood of Jesus. We would be mistaken to think that this is entirely spiritual, for clearly Jesus had real flesh and blood and would really die. Even more, there is real life bestowed to the person who partakes. In light of the failure of the forefathers, this final stage of the challenge of Jesus consists in surrendering one’s own life and laying hold of another’s.

6:54 “The one who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him on the last day” (ὁ τρώγων μου τὴν σάρκα καὶ πίνων μου τὸ αἷμα ἔχει ζωὴν αἰώνιον, κἀγὼ ἀναστήσω αὐτὸν τῇ ἐσχάτῃ ἡμέρᾳ). Jesus restates the same message, though this time positively and with clear first-person reference: “my flesh” (μου τὴν σάρκα) and “my blood” (μου τὸ αἷμα). The continuing reference to Christ’s raising the believer on the last day must be important (cf. vv. 39, 40, 44). There is also an interesting switch in the Greek term used for “eating.” Instead of using the term for “eat” (ἐσθίειν) used in v. 53, here another term for “eat” (τρώγειν) is used. While the terms have a high degree of overlap, if anything the latter term is more aggressive—more actively or more audibly eaten—so that some suggest the translation, “munch” or “gnaw.”45 There is no reason to deny a distinction between the two terms, even if it is minute. The change suggests a rhetorical thrust, a forceful explication of the reality of the eating being depicted.

6:55 “For my flesh is real food, and my blood is real drink” (ἡ γὰρ σάρξ μου ἀληθής ἐστιν βρῶσις, καὶ τὸ αἷμά μου ἀληθής ἐστιν πόσις). Jesus had already declared that the food that filled their bellies was not true food, for it was not food “that endures into eternal life” (v. 27). Rather, Jesus describes his food using the adverb “real” (ἀληθής). This is not to be taken as literalizing the food, for Jesus is speaking about something to which food only signifies; yet neither can it be taken as mere metaphor, since something is being signified that is best depicted with the imagery of food.46 Rather, and with more nuance, Jesus is declaring that the food he gives—that the food he is—is real, that is, it fulfills the ideal, archetypal function of food and drink, for its caloric effects secure eternal life. No other food was as qualitatively real as his food, for nothing and no one else can provide eternal life—not the food given to the large crowd (6:1–15), or the manna of Moses, or any other food humanity can discover or invent for itself. His food, his body, is the real food; his drink, his blood, is the real drink. Such pointed language directs our minds to his body and blood, that is, to the cross.

6:56 “The one who eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me and I in him” (ὁ τρώγων μου τὴν σάρκα καὶ πίνων μου τὸ αἷμα ἐν ἐμοὶ μένει κἀγὼ ἐν αὐτῷ). Jesus gives further explanation to eating his flesh and blood when he describes it as a mutual indwelling: those who eat and drink remain in him, and he in them. It is the eating and drinking that makes possible this coparticipatory union. The term “remain” (μένει) is one of the central terms in the Gospel; the Father “remains” in the Son (14:10), the Spirit “remains” upon Jesus (1:32–33), and believers “remain” in Christ and he in them (15:4). The term is depicting a coparticipatory existence, where the “being” of the believer is determined or regulated by Jesus.47 It is nothing less than a depiction of an intimate relationship. The apostle Paul considers himself to have shared so deeply in Christ that the crucifixion of Christ was in a real way also his death, with his life being lived (empowered) by Christ in him (Gal 2:20). This is the first appearance of this concept in the Gospel; later in the Gospel Jesus will give further explanation concerning this mutual indwelling (see 8:31–32; 14:20; 15:4–10; 17:21–23).

6:57 “Just as the living Father sent me and I live because of the Father, so the one who eats me will also live because of me” (καθὼς ἀπέστειλέν με ὁ ζῶν πατὴρ κἀγὼ ζῶ διὰ τὸν πατέρα, καὶ ὁ τρώγων με κἀκεῖνος ζήσει δι’ ἐμέ). The concept of life which has been so central to the dialogue thus far continues to be prominent in this further explanation by Jesus. Just as Jesus is the living bread (v. 51), so also is the Father now described as the “living Father.” The life that Jesus provides is connected to the Trinitarian identity of God from Father through Son and—as we will soon see—in cooperation with the Spirit (cf. 14:17). The statement draws on what Jesus has already stated in 5:21–30 (see comments on 5:24). The Son, the representative of the Father (1:18), is to be eaten, but the meal was produced by the very fullness of God.

6:58 “This is the bread that came down from heaven, not as the fathers who ate and died, the one who eats this bread will live forever” (οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ ἄρτος ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβάς, οὐ καθὼς ἔφαγον οἱ πατέρες καὶ ἀπέθανον· ὁ τρώγων τοῦτον τὸν ἄρτον ζήσει εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα). This verse concludes Jesus’s statement in the sixth verbal exchange with the Jews and serves as a summary of the entire dialogue. By returning to the third person and with the use of “this” (οὗτός), which has no proper antecedent, Jesus ends by summarizing his message. In short, Jesus offers the Jews real food and real life. To reject this offer would be to reject God himself. Through Jesus, God has personally rebuked the “grumbling” and “arguing” people to whom he showed such great love in the wilderness. No longer! Out of this context and heritage comes the challenge Jesus has launched against the Jews (and—even more—against the reader and the world; cf. v. 51). All their questions have now been answered (vv. 42, 52). It is now time for the Jews to respond. Will they eat this bread and live? The answer will be revealed by the narrative shortly (v. 61).

6:59 He said these things while he was teaching in a synagogue in Capernaum (Ταῦτα εἶπεν ἐν συναγωγῇ διδάσκων ἐν Καφαρναούμ). The dialogue comes to a close with a brief intrusion by the narrator, who provides closure by revealing where the event took place. The reader had already been informed that the location was Capernaum (v. 24); the new insight here is that the dialogue occurred “in a synagogue while he was teaching” (ἐν συναγωγῇ διδάσκων). Although John often begins a new section with the setting, it is not uncommon for the setting to bring a section to a close (cf. 8:20). There is historical evidence that synagogue services allowed such exchanges, all the more if the lectionary reading on that day was Exodus 16.48 But such specific evidence is not needed, for Jesus’s presence in a synagogue, surrounded by a swarming crowd interested in the wrong things, became the perfect context for him to offer his divine challenge. In fact, Jesus will later declare when confronted by the high priest about his teaching that he spoke “openly to the world,” teaching “in synagogues and the temple, where all the Jews come together,” saying nothing in secret (18:19–20). In this synagogue on this day, it was not the Jews who came to speak to God, it was God who came to speak to them—in the form of a social challenge.

6:60 Then after many of his disciples had heard they said, “This message is offensive! Who is able to accept it?” (Πολλοὶ οὖν ἀκούσαντες ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ εἶπαν, Σκληρός ἐστιν ὁ λόγος οὗτος· τίς δύναται αὐτοῦ ἀκούειν;). With the dialogue concluded, the narrator now turns to the reaction of those present. Those responding to Jesus here transitions from the “crowd/Jews” to “many of his disciples” (Πολλοὶ ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ). This transition suggests that the dialogue scene has shifted its focus more narrowly from the crowd in general and the Jewish opponents of Jesus to a circle of “disciples,” more inclusive than the Twelve (cf. v. 67). By the standards of first-century Judaism, they were disciples of a rabbi.

This larger circle of disciples is no less offended than the Jews when confronted by his teaching. They call Jesus’s message “offensive” (Σκληρός), a term which refers by itself to something “hard” or “unpleasant” but in relation to people is something that “pertains to causing an adverse reaction because of being hard or harsh.”49 These “disciples” can only ask in disgust, “Who is able to accept it?” (τίς δύναται αὐτοῦ ἀκούειν;).

6:61 After Jesus had seen in himself that his disciples were grumbling concerning this he said to them, “Does this offend you?” (εἰδὼς δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἐν ἑαυτῷ ὅτι γογγύζουσιν περὶ τούτου οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Τοῦτο ὑμᾶς σκανδαλίζει;). The narrator introduces Jesus’s response to these “disciples” by revealing that Jesus was aware of their thoughts, denoted by the awkward prepositional phrase, “in himself” (ἐν ἑαυτῷ). The phrase serves to highlight the supernatural awareness of Jesus—an insight regarding Jesus that has been seen previously (v. 43; cf. 1:47–48; 2:24–25; 4:18). These “disciples” respond in a manner conspicuously similar to the response of the Jews to Jesus and of their forefathers to God (see comments on vv. 41, 43). While it is likely that the eating of his flesh and drinking of his blood is the most blatant source of offense, it is best to include around it the entirety of Jesus’s message.50

6:62 “Then, what if you see the Son of Man ascending to where he was before?” (ἐὰν οὖν θεωρῆτε τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἀναβαίνοντα ὅπου ἦν τὸ πρότερον;). Jesus offers another question, though this one is more difficult to interpret, since the apodosis is not given (i.e., the “if” clause is not followed by a “then” clause, thus requiring the inclusion of “what” to make a complete thought). It is likely that Jesus is pressing further his first question in order to say, “Would you still be offended?” The combination of “if” (ἐὰν) and the subjunctive, “see” (θεωρῆτε), refers to the future.51 Because the ascension is lacking in the Gospel (besides the implied version in 20:17), some interpreters suggest the “ascending” here refers to Jesus’s exaltation on the cross (in a similar manner as found in 3:14). But this seems to work against the context of the pericope with the focus on Jesus’s person and work as the Son of Man, as well as the message Jesus has been declaring about himself since the Gospel’s inception (see 1:51).

When we recall the prologue, the reader is then able to see the referent behind the words, “Where he was before” (ὅπου ἦν τὸ πρότερον). He, the Word, “was in the beginning with God” (1:2). It is the Word, descended from the Father, who will “ascend” to his rightful place again. Such a statement coalesces perfectly with the emphasis of the pericope on the “descending” of the Son, the bread of life (cf. vv. 33, 38, 41–42, 50–51, 58). It is not, then, that these “disciples” are rejecting the cross; it is rather that they are rejecting God himself. For this reason, the Word confronts these so-called disciples with his full identity and challenges them to reconsider. Jesus seems to be saying, “If you reject me and my words, what will you do if (and when) you see me as I truly am in glory, ascending to my rightful place of power and authority? What, then, would you do with your unbelief and offense?”52

6:63 “The Spirit is giving life, the flesh cannot help anything; the words which I have spoken to you are spirit and are life (τὸ πνεῦμά ἐστιν τὸ ζῳοποιοῦν, ἡ σὰρξ οὐκ ὠφελεῖ οὐδέν· τὰ ῥήματα ἃ ἐγὼ λελάληκα ὑμῖν πνεῦμά ἐστιν καὶ ζωή ἐστιν). Pressing further his challenge against their unbelief and offense, Jesus gives commentary on their state of rebellion. Jesus declares that the Spirit, which can only be the Holy Spirit, “is giving life” (ἐστιν τὸ ζῳοποιοῦν). The participle serves to highlight aspectual force, which in this case is the present, even ongoing, occurrence of the giving of life (cf. 2 Cor 3:6).53 This is contrasted with the emphatic, double-negative denial of “the flesh” (ἡ σὰρξ), which is spoken of as helpless; it “cannot provide anything” (οὐκ ὠφελεῖ οὐδέν).54 The concept of flesh is not to be simply imported from the apostle Paul, for in John “flesh” is merely the body and its limitations. The point is quite simple: “flesh” and “spirit” are different spheres of reality, each producing offspring like itself.55 “Neither can take to itself the capacity of the other.”56 This verse has many similarities to what Jesus said to Nicodemus (see comments on 3:6).

Thus, when Jesus declares that “the words” (τὰ ῥήματα) he has spoken to these so-called disciples “are spirit and are life” (πνεῦμά ἐστιν καὶ ζωή ἐστιν), he rebukes them by way of reminder that he is the one who gives life (5:21), he is the assigned Judge (5:22), and it is the Father alone who wills belief (cf. v. 37–39, 44). Interpreters who have relied heavily on a eucharistic interpretation of this pericope have difficulty with this verse and usually disassociate this section (vv. 60–71) from the preceding verses because it does not match the emphasis placed on the “flesh” of Jesus.57 But that confuses the “flesh” in general with the flesh of Jesus Christ, which is the unique flesh that provides for our “flesh” the beginnings of eternal life (see especially the comments on v. 51). The contrast, then, is not entirely between all flesh and spirit, but between the “flesh” of dying humanity and the living flesh of Jesus, the flesh of the bread of life—the flesh of the crucified God.58 It is in the person of Jesus where our flesh, which he himself bore, becomes united with his life.

6:64 “But there are some of you who do not believe.” For Jesus had known from the beginning who they are that do not believe and who it is who will hand him over (ἀλλ’ εἰσὶν ἐξ ὑμῶν τινες οἳ οὐ πιστεύουσιν. ᾔδει γὰρ ἐξ ἀρχῆς ὁ Ἰησοῦς τίνες εἰσὶν οἱ μὴ πιστεύοντες καὶ τίς ἐστιν ὁ παραδώσων αὐτόν). Jesus adds to his rebuke its logical conclusion: “There are some of you” (εἰσὶν ἐξ ὑμῶν τινες) who do not believe. Just as he revealed himself to them, so also does he now reveal to them their true selves, similar to how he earlier unmasked the unbelief of “the crowd” (v. 36), of “the Jews” in Jerusalem (5:38), and even earlier of Nicodemus and those he represented (3:11–12).59 The more Jesus became an offense (vv. 60–61), the more visible their unbelief. That only “some” and not all are declared such is not merely a gentler statement but a sign of hope that there is the possibility of change.

The narrator provides an explanatory intrusion, something common to the reader by now, which provides an important insight: none of this was a surprise to Jesus. The one who knows the nature of humanity (cf. 2:24–25) also knows the nature of these followers. The narrator explains that Jesus had known of these disbelievers “from the beginning” (ἐξ ἀρχῆς), a phrase that harks back to 1:1, which implied that the Word partook of the eternal counsels of God.60 It is strange that the narrator inserts here the future betrayal of Jesus by one of his disciples. Just as Jesus knew in the past that some disciples would not believe in the present, so also he knows in the present that a certain disciple will reveal his unbelief in the future. The allusion to Judas here also serves as an allusion to the cross, the very thing “some of” these disciples are rejecting.

6:65 And he said, “For this reason I told you that no one is able to come to me unless it has been given to him from the Father” (καὶ ἔλεγεν, Διὰ τοῦτο εἴρηκα ὑμῖν ὅτι οὐδεὶς δύναται ἐλθεῖν πρός με ἐὰν μὴ ᾖ δεδομένον αὐτῷ ἐκ τοῦ πατρός). Jesus concludes his postdialogue conversation with the so-called “disciples” with a statement that reemphasizes a fundamental theme of the entire pericope: the primary agent of faith is the Father. Referring back to what he said in vv. 37–39, 44, Jesus declares “no one is able to come to me” (οὐδεὶς δύναται ἐλθεῖν πρός με), that is, have faith in or believe in him, unless “it has been given to him” (ᾖ δεδομένον αὐτῷ). This latter phrase is conveyed with a perfect passive participle that nearly bursts with theological significance. Faith is not just a general gift but is a specific gift, something upon which the Christian is utterly dependent. From start to finish there is no such thing as an independent Christian. Without the Father, there would be no children. It is the Father who must give the “right” (1:12); salvation is “from God” (1:13). In a real way, this is the ultimate rebuke of Jesus to his interlocutors in this challenge dialogue. They lose not only because of their own lack of faith but also because the Father was, quite simply, against them from the start.

6:66 From this time many of his disciples fell away and were no longer following him (Ἐκ τούτου [οὖν] πολλοὶ ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ ἀπῆλθον εἰς τὰ ὀπίσω καὶ οὐκέτι μετ’ αὐτοῦ περιεπάτουν). After Jesus brings further clarity to his message to the crowd of Jews, the so-called disciples conclude their interest in him. The verse is filled with peculiar language. “From this time” (Ἐκ τούτου) could also be translated as “for this reason”; in fact both senses are likely to be simultaneously intended. The so-called disciples deny their rabbi by their actions. While the verb “following” (περιεπάτουν) could also be translated as “walking,” in the context of first-century Judaism the term stands for the act of a follower, that is, a disciple.61 To walk no longer with one’s teacher was to resign formally from his instruction and disassociate from his message.

6:67 Then Jesus said to the Twelve, “You do not want to leave also, do you?” (εἶπεν οὖν ὁ Ἰησοῦς τοῖς δώδεκα, Μὴ καὶ ὑμεῖς θέλετε ὑπάγειν;). Jesus now turns from the wider circle of disciples (cf. v. 60) to his more intimate disciples, whom the Gospel describes for the first time as “the Twelve.” In a question this form of negation, “not” (Μὴ), produces either “a strong deprecatory tone . . . or puts a suggestion in the most tentative and hesitating way.”62 The former is more likely here. The context builds the dramatic force of this question, for the disciples have witnessed in detail the challenge presented to the Jews and then to the wider circle of disciples. And it is the same challenger that now poses a loaded question to them.

6:68 Simon Peter answered to him, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτῷ Σίμων Πέτρος, Κύριε, πρὸς τίνα ἀπελευσόμεθα; ῥήματα ζωῆς αἰωνίου ἔχεις). Simon Peter, known in the Synoptics for being outspoken (cf. Matt 16:22), speaks on behalf of the Twelve with words that serve as a confession of allegiance and belief. His return question to Jesus, “Lord, to whom shall we go?” (Κύριε, πρὸς τίνα ἀπελευσόμεθα;), is to be viewed in sharp contrast to the response of the so-called disciples who had already left, that is, “fell away” (v. 66). Quite simply, the Twelve believe Jesus, for as Peter explains, “You have the words of eternal life.” With these words, Peter reveals a true grasp of Jesus’s message and an awareness of what is at stake—life itself (see comments on v. 53).

6:69 “And we have believed and have known that you are the Holy One of God” (καὶ ἡμεῖς πεπιστεύκαμεν καὶ ἐγνώκαμεν ὅτι σὺ εἶ ὁ ἅγιος τοῦ θεοῦ). Peter adds to the confession of the Twelve by declaring with two perfect-tense verbs—“we have believed and have known”—that Jesus is “the Holy One of God” (ὁ ἅγιος τοῦ θεοῦ). The disciples had from early on been more than willing to see Jesus as the Messiah (cf. 1:41, 45, 49), but now they see him and their understanding of “Messiah” as something more. There are no parallels for this title in Judaism.63 Rather, rooted in the words of Jesus himself, “the Holy One of God” is the emissary, the one who came descending and ascending, the “I AM,” the “bread of life,” the revelation of God, the Judge and the life, the Son of Man. Peter is confessing what he has been “given” to see and believe. It is to all of this that the Gospel has been serving as witness. In Jesus is found everything God wants to do and is doing.

6:70 Jesus answered to them, “Have I not chosen you, the Twelve, yet one of you is the devil?” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Οὐκ ἐγὼ ὑμᾶς τοὺς δώδεκα ἐξελεξάμην, καὶ ἐξ ὑμῶν εἷς διάβολός ἐστιν;). After such a lofty confession the reader might have expected Jesus to embrace the Twelve with joy, but even to them (not just to Peter) a challenge of sorts ensues. With the stroke of one forceful rhetorical question, Jesus not only reminds them that they were “chosen” (ἐξελεξάμην) by him but also declares their faith to be still lacking—for “one of you is the devil” (ἐξ ὑμῶν εἷς διάβολός ἐστιν). What v. 71 will explain is that Judas, “the one,” will serve as a pawn for Satan, who so operates behind failing humans that his malice becomes theirs.64 By combining the chosen eleven with “the one,” Jesus positions the sovereign work of God on both sides of faith. Not only were the Twelve sovereignly elected by God to have faith, but even the unfaithfulness of Judas is to be subsumed under the election of God, even if for a contrary task.

6:71 He was speaking about Judas, son of Simon of Iscariot, for he was about to hand over Jesus, even though he was one of the twelve (ἔλεγεν δὲ τὸν Ἰούδαν Σίμωνος Ἰσκαριώτου· οὗτος γὰρ ἔμελλεν παραδιδόναι αὐτόν, εἷς [ὢν] ἐκ τῶν δώδεκα). The narrator concludes the pericope with an explanatory intrusion that serves to explain Jesus’s comments and connect the scene and its message to the developing plot of the Gospel. This information only serves to make explicit what had already been implied (see comments on v. 64). The one behind whom the devil will act is “Judas” (Ἰούδαν), modified by two genitives providing his family name and place of origin, “son of Simon of Iscariot” (Σίμωνος Ἰσκαριώτου).65 This statement provides a reality check for the reader by putting flesh on Jesus’s rebuke of and insight into the human condition.

Theology in Application

In a scene reminiscent of Moses and the Israelites in the wilderness, Jesus stands with a horde of followers who want to make him their king. But their vision of him—of God—was drenched with sinful illusions. So Jesus initiates a challenge to his followers, and through his self-revelatory confession challenges not only the “God” the crowd claims to seek but also their self-righteousness. In this pericope the reader of the Fourth Gospel is exhorted to examine the object of their worship, and even more to see life itself as founded upon the work of God through the Son. While the length of the pericope might prohibit the preacher from handling all fifty verses at once, the overall message should at least be maintained in the context of the dialogue and its movement.

Who (or What) Are You Following?

This pericope contains some of the most theological and christological statements of Jesus in the entire Gospel, even in all four Gospels. And on their own they need to be studied and reflected upon. But when viewed in the context of a social challenge dialogue, these statements serve as a rebuke of the reader and all humanity for the objects of our worship. The pericope shows the self-focused infatuation of the crowd and their self-interest in Jesus. Yet Jesus cuts right to the heart of the matter—the food their stomachs crave versus real food for their souls. The rest of the dialogue revolves around this distinction.

In the context of the dialogue over real food, another issue is clearly presented to us: our stomachs (i.e., our desires and passions) cannot be trusted. Our desires are self-seeking, rooted in our skewed perception of what is real and what really matters. The gods of this world are perishing; they are figments of our fallen and limited imaginations. Peter may not have fully understood “the Holy One of God” (v. 69), but he at least phrased the right question: “Lord, to whom shall we go?” As Luther explained, this is the message of the Christian church to itself and to the world, declaring in our hearts that he will satisfy us and testifying to the world about the satisfaction we have found in Christ alone.66

The Argument from Election

This pericope contains some of the clearest and strongest statements by Jesus that God is the primary agent of salvation. But what might be most significant is that these statements are not just isolated propositions but are used as an argument against the crowd and the Jews in the midst of the social challenge. Jesus is careful to explain to the crowd and the Jews that it is not they who reject God, but God who has preemptively already rejected them. “Unless it has been given to him from the Father” (v. 65), no one can come to Jesus. Such a statement demands that the potential for belief be removed from the individual, for faith is a gift from the Father alone. Just as there is no independent fetus or infant, so also from start to finish there is no such thing as an independent Christian. Without the Father, there simply would be no children. It is the Father who must give the “right” (1:12). It cannot be given from the blood of humanity or the desire of the flesh or the will of a person; it must be “from God” (1:13). In the context of the social challenge, the role of rejection has been reversed. It is not the crowd/Jews/disciples who are rejecting Jesus; rather, it is God rejecting them.