Chapter 27

John 13:21–30

Literary Context

This pericope is the second of a two-part introduction to the farewell discourse, setting the historical and theological context in which Jesus’s fourth and most complex monologue will take place. In the first part of the introduction (13:1–20), Jesus enacted the service of the cross for his disciples with the washing of their feet. In the second part of the introduction Jesus will announce his betrayal, setting into motion the historical (Judas) and the cosmological (Satan) conflict that will only find resolution in his death and resurrection. In this scene Jesus reveals that his “hour” had come and that his battle was not merely with those on the outside, but even with one on the inside, revealing that his person and work confront not only the cosmological opposition of Satan but also the sin that entangles every person, including the reader of the Gospel.

- VII. The Farewell Discourse (13:1–17:26)

- A. Introduction: The Love of Jesus (13:1–30)

- 1. Jesus and the Washing of His Disciples’ Feet (13:1–20)

- 2. Jesus Announces His Betrayal (13:21–30)

- B. The Farewell Discourse (13:31–16:33)

- 1. Prologue: Glory, Departure, and Love (13:31–38)

- 2. I Am the Way and the Truth and the Life (14:1–14)

- 3. I Will Give You the Paraclete (14:15–31)

- 4. I Am the True Vine (15:1–17)

- 5. I Have Also Experienced the Hate of the World (15:18–27)

- 6. I Will Empower You by the Paraclete (16:1–15)

- 7. I Will Turn Your Grief into Joy (16:16–24)

- 8. Epilogue: Speaking Plainly, Departure, and Peace (16:25–33)

- C. Conclusion: The Prayer of Jesus (17:1–26)

- A. Introduction: The Love of Jesus (13:1–30)

Main Idea

Even at his betrayal, Jesus communed with his disciples. Christians, “beloved disciples” of Jesus, should find their rest in his person, reclining on his chest and remaining in permanent communion with him and his church.

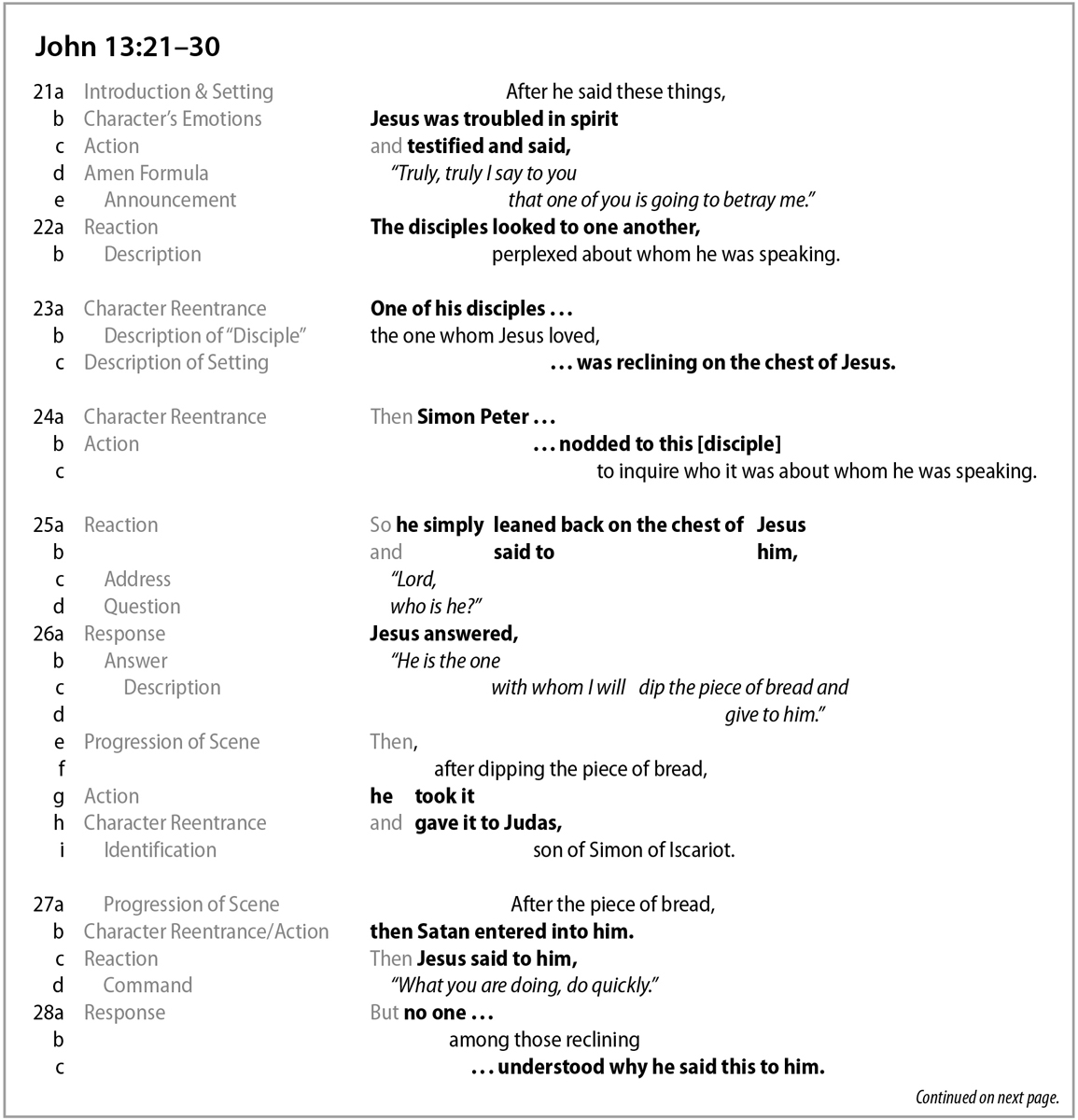

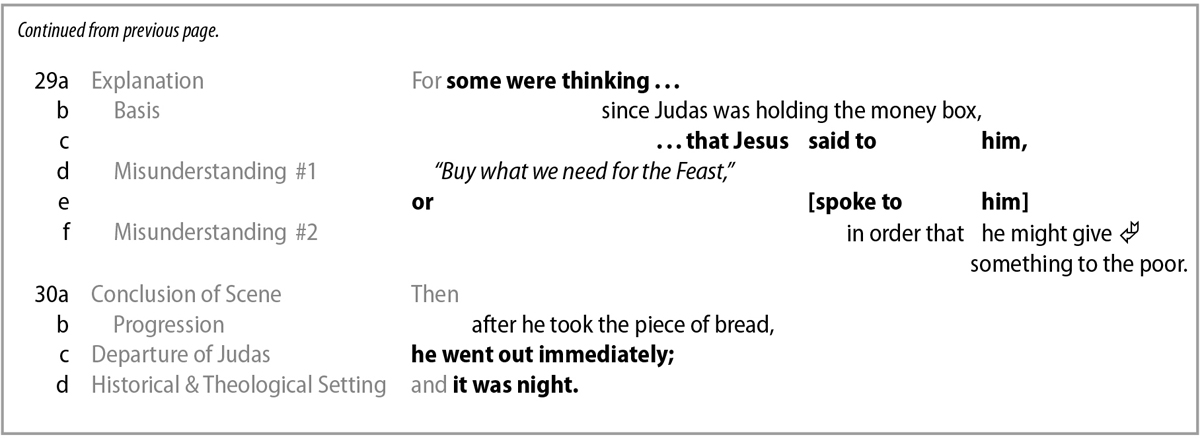

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

This pericope is a combination of a basic story form and a dialogue. Unlike the previous pericope (13:1–20), which moved in the sequence of action-dialogue-monologue, in this pericope a dialogue (vv. 23–26) is framed on both sides by narrative action (vv. 21–22 and vv. 27–30). What is similar, however, is the combination of action with dialogue, which the reader should understand as working as part of an integrated movement. Jesus introduces the issue of the pericope, followed by the response of the disciples in vv. 21–22. In vv. 23–26 a dialogue ensues, prompted by Peter, between the Beloved Disciple and Jesus that provides insight into the prophetic and cryptic statement of Jesus. This dialogue is unique in that it is a symbol-laden dialogue with few words. Finally in vv. 27–30 the narrator turns his attention to Judas, the betrayer of Jesus, describing his transition from his association with Jesus and the disciples to his new association with Satan. As the second of a two-part introduction to the farewell discourse, the pericope guides the reader to see even more clearly the historical and cosmological context of opposition to Jesus.

Exegetical Outline

- 2. Jesus Announces His Betrayal (13:21–30)

- a. The Prophecy of a Betrayer (vv. 21–22)

- b. Jesus’s Dialogue with the Beloved Disciple (vv. 23–26)

- c. The Entrance of Satan and Departure of Judas (vv. 27–30)

Explanation of the Text

Since this entire section of the Gospel is replete with interpretive issues, we refer the reader to the first pericope of this section where we provided an overview of the nature (genre), literary structure, and function of the farewell discourse (see comments before 13:1).

13:21 After he said these things, Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified and said, “Truly, truly I say to you that one of you is going to betray me” (Ταῦτα εἰπὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἐταράχθη τῷ πνεύματι καὶ ἐμαρτύρησεν καὶ εἶπεν, Ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν ὅτι εἷς ἐξ ὑμῶν παραδώσει με). The phrase “after he said these things” (Ταῦτα εἰπὼν) serves as an introductory expression and signals to the reader that this is a new pericope and a new phase in the story.1 The new phase is introduced further by a summarizing statement by the narrator depicting the emotional condition of Jesus: “Jesus was troubled in spirit” (ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἐταράχθη τῷ πνεύματι). Jesus has been depicted as “troubled” before, with the most revealing example occurring at the death of Lazarus. The use of a related phrase here reveals a similar emotional state, one in which Jesus is filled with deep emotion as the “hour” draws near (see comments on 11:33; cf. 12:27).

Beginning with an authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51), Jesus announces that there is a betrayer among the disciples. Jesus had been prophetically aware of this moment much earlier, as had the reader, who was given specific insight into the betrayal and the betrayer (see 6:64, 71; cf. 12:4; 13:2, 11). The disciples had only been told cryptically that one of them was the devil (see 6:70; cf. 13:18). Like the original announcement, it is best to understand this more direct statement not only as a “prophecy” of what will take place but also as an accusation against his disciples, those sharing with him in this intimate meal, out of whom would come the betrayer (see comments on 6:70).

13:22 The disciples looked to one another, perplexed about whom he was speaking (ἔβλεπον εἰς ἀλλήλους οἱ μαθηταὶ ἀπορούμενοι περὶ τίνος λέγει). The prophecy and accusation of Jesus caused a stir among the disciples. Taking their eyes away from Jesus, they “looked to one another” (ἔβλεπον εἰς ἀλλήλους). Rather than asking Jesus directly, they remain silent and communicate at first only with their eyes—the first of several “wordless” communications in this pericope.2 They look to each other as a way of expressing their perplexity regarding the identity of the one about whom Jesus speaks (the prophecy), as well as in regard to themselves (the accusation).3

13:23 One of his disciples, the one whom Jesus loved, was reclining on the chest of Jesus (ἦν ἀνακείμενος εἷς ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ ἐν τῷ κόλπῳ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ, ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς). The narrator focuses his attention on one disciple in particular, with whom Jesus will have a short dialogue (vv. 23–26). This anonymous disciple is simply described as “the one whom Jesus loved” (ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς) or, more traditionally, “the Beloved Disciple.” This is the first of several occurrences of the Beloved Disciple in the Gospel (see also 19:25–27, 35; 20:1–10; 21:1–7, 20–24; cf. 1:40; 18:15). The anonymity of the Beloved Disciple can only be intentional, for it is highly unlikely that the evangelist was unaware of this individual. As we discussed earlier, anonymity is itself a narrative tool to develop both plot and characterization (see comments on 1:40). It serves “to focus the readers’ attention on the role designations that flood into the gap that anonymity denotes,”4 a gap not to be filled until the Gospel’s conclusion (see comments on 21:24; see Introduction).

This first occurrence of the Beloved Disciple does reveal some important details about his identity. First, it is likely that the Beloved Disciple is one of the “Twelve.” While the Gospel is not explicit on this point, this is the implicit assumption in this scene and in later appearances in the narrative. This is not to suggest the Gospel is only (or even primarily) concerned with the historical referent, as the next point will make clear.

Second, while the Beloved Disciple is a “real” disciple, by using anonymity the Gospel establishes the Beloved Disciple as not only a figure in history but as a character in the narrative. In this way, the anonymity functions as a literary device that forces the reader to engage with the Beloved Disciple primarily by his narrativized identity. For the reader then, the identity of the Beloved Disciple is not simply who he is (behind the narrative) but what he is (within the narrative). The anonymity of the Beloved Disciple depicts the “ideal disciple,” one having special access and intimate relationship with Jesus (see comments on 21:24).5 This in no way minimizes the historical reality of the Beloved Disciple, but creates alongside his historical identity a narrativized identity and role that is significant to the message of the Gospel.

Third, the narrator depicts the Beloved Disciple in “a position that signals a privileged relationship,” made clear by the description of him as “reclining on the chest of Jesus” (ἦν ἀνακείμενος ἐν τῷ κόλπῳ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ).6 While this is not best compared too strictly with the similar language in 1:18 (“Son . . . in the bosom [chest] of the Father”) that relates Jesus to the Father (a cosmological union), it certainly intends to communicate a deep and mutual commitment between Jesus and his disciple, befitting the ancient context and dining customs (a historical union). For 1:18 makes clear that Jesus’s intimate relationship with the Father is intended to provide an intimate relationship between God and all disciples.7 The unique relationship between Jesus and the Beloved Disciple is not mentioned explicitly here, but it may stem from a personal friendship or even from a relation of kin (see comments on 19:25–27). It is important to note that meals in the ancient world did not involve tables with chairs but involved reclining on couches, usually U-shaped (called a triclinium) around a low table. Participants would support themselves on their left elbows and eat with their right hands.8 The position of the Beloved Disciple is not to be understood as resting “on top of” Jesus, but as reclining “by the side of” Jesus. Although our less idiomatic translation helps make the important connection to 1:18, it could mislead the modern reader in regard to physical position.

Fourth, the Beloved Disciple is also in a unique relationship, at least narratively, with Peter (v. 24). Most of the appearances of the Beloved Disciple are in direct connection with Peter and will be noted in the commentary as the narrative progresses. As we will see, this is not to be viewed as a competition but as a depiction of the different roles and kinds of disciples. This is, however, the first of four comparison-like depictions of Peter and the Beloved Disciple (13:22–25; 20:3–9; 21:7; 21:20–23).

Finally, and most obviously, Jesus “loved” (ἠγάπα) this disciple. The Beloved Disciple is not the only one Jesus is said to have loved, for not only is Jesus described as loving Martha and Mary (11:5), Lazarus (11:36), and all his disciples (13:1; 15:19), but God himself is described as loving the whole world (3:16).9 But befitting his role as an “ideal” disciple, this serves to portray the uniquely loving relationship that exists between Jesus and his disciples.

13:24 Then Simon Peter nodded to this [disciple] to inquire who it was about whom he was speaking (νεύει οὖν τούτῳ Σίμων Πέτρος πυθέσθαι τίς ἂν εἴη περὶ οὗ λέγει). The relationship between Peter and the Beloved Disciple is made evident by the response Peter gives to him in regard to Jesus’s statement. The narrator describes how Peter “nodded” (νεύει) to the Beloved Disciple; that is, Peter made some kind of motion to him as a signal, probably by inclining his head.10 As much as the Beloved Disciple is in close communion with Jesus, this nonverbal communication between Peter and the Beloved Disciple suggests that they are similarly in close relationship, for whom words were not even needed.11 Peter wanted to know “about whom” (περὶ οὗ) Jesus spoke, so he signaled to the Beloved Disciple in order that he might ask Jesus to be more specific.

13:25 So he simply leaned back on the chest of Jesus and said to him, “Lord, who is he?” (ἀναπεσὼν οὖν ἐκεῖνος οὕτως ἐπὶ τὸ στῆθος τοῦ Ἰησοῦ λέγει αὐτῷ, Κύριε, τίς ἐστιν;). In response to the signal given by Peter, the Beloved Disciple “leaned back” (ἀναπεσὼν) toward Jesus, so much so that the narrator claims he was resting “on the chest of Jesus” (ἐπὶ τὸ στῆθος τοῦ Ἰησοῦ). With the combination of the Greek words translated “so” (οὖν) and “simply” (οὕτως), the narrator focuses the reader’s attention on the wordless communication of the Beloved Disciple, who responds to Peter’s signal “without further ado,” another possible translation in place of “simply” (οὕτως).12 The nature of this description reveals the kind of intimate closeness the Beloved Disciple is able to express with Jesus. At this moment a disciple of Jesus, a mere man, has immediate and personal access to God himself.

The word translated as “chest” (τὸ στῆθος) in this verse is different from the word translated as “chest” (τῷ κόλπῳ) in v. 23. While the terms are generally synonymous, the difference is certainly intentional, probably serving to strengthen or emphasize the closeness of this disciple to Jesus, for he is literally “on” Jesus (on the use of two related words in close proximity, see comments on 13:10).13 The Western reader must be immediately reminded that such physical closeness was (and is) quite different in an Eastern context. In many parts of the world today, men walk down the street holding hands as a sign of friendship, not as a sign of homosexuality. This is an especially common practice between two men operating together in a business relationship, reflecting mutual respect and trust. With this in view, the actions of the Beloved Disciple become wordless communication that shows mutual trust and respect, even intimacy, between Jesus and the Beloved Disciple. Thus, when he finally does speak (“Lord, who is he?” [Κύριε, τίς ἐστιν;]), the Beloved Disciple speaks as one who has been given the “right” to ask such questions because he is, quite simply, “in Christ.”

13:26 Jesus answered, “He is the one with whom I will dip the piece of bread and give to him.” Then, after dipping the piece of bread, he took it and gave it to Judas, son of Simon of Iscariot (ἀποκρίνεται Ἰησοῦς, Ἐκεῖνός ἐστιν ᾧ ἐγὼ βάψω τὸ ψωμίον καὶ δώσω αὐτῷ. βάψας οὖν τὸ ψωμίον [λαμβάνει καὶ] δίδωσιν Ἰούδᾳ Σίμωνος Ἰσκαριώτου). Befitting this pericope’s focus on “wordless” communication, Jesus designates the betrayer not by his name but by his actions. Only the narrator gives the name of Judas, son of Simon of Iscariot, to the reader.

Jesus explains that the betrayer is the one “with whom I dip” (ᾧ ἐγὼ βάψω), with the first-person pronoun giving emphasis to Jesus’s action. This action is made especially significant because of the intimacy of meals in the first-century context. Social gatherings, but especially meals, were intimate affairs. A person did not just eat with anyone. To eat with a person was to show approval and equality. This explains why Jesus was denounced by the Pharisees and scribes for eating with sinners: “This man welcomes [gathers with] sinners and eats with them” (Luke 15:2). Thus, when Jesus announces the betrayal with actions (not words), he too signals to those present that the forthcoming actions of Judas are a betrayal.14 The fact that the narrator, not Jesus, makes Judas the explicitly stated referent suggests that Jesus’s wordless signal is intended to depict Judas in a manner similar to the Beloved Disciple as an ideal disciple, although clearly in a negative sense. In this pericope “Judas becomes the archetypal defector.”15 Judas becomes a model in the Fourth Gospel for disbelief, for breaking away from Christian fellowship and intimacy and becoming an agent of Satan (as v. 27 will establish).16

13:27 After the piece of bread, then Satan entered into him. Then Jesus said to him, “What you are doing, do quickly” (καὶ μετὰ τὸ ψωμίον τότε εἰσῆλθεν εἰς ἐκεῖνον ὁ Σατανᾶς. λέγει οὖν αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ὃ ποιεῖς ποίησον τάχιον). The final section of the pericope (vv. 27–30) begins with the introduction of Satan. Continuing the theme of “wordless” signals, the narrator connects the entrance of Satan “into” Judas with the giving of the piece of bread. This is the only place in the Gospel that Satan is mentioned by name. Interestingly, only the reader is given access to the interpretation of this signal. The “odd expression”17 of the sharing of bread between Jesus and Judas creates something like a contract or covenant between them, initiated by Jesus, through which Judas was given the right or authority to do what he was going to do. Like the Spirit of God entering those chosen by God in the OT, it was not until that moment—“then” (τότε)—that Satan “entered into” (εἰσῆλθεν εἰς) Judas. This event cannot be described with any greater clarity or precision, for this is a cosmological event that needed the narrator’s insight.

Jesus’s statement to Judas stems from his authority—“no one takes [my life] from me, but I lay it down by myself” (10:18). As much as Jesus has been serving Judas (e.g., washing his feet), even in the betrayal Judas is technically serving Jesus. The urgency Jesus demands befits the significance of “the hour” in the Gospel (see comments on 2:4). All that has transpired, even the betrayal of Judas, has been rooted in his plan, for everything had already been determined by God himself. Thus, Judas, and even Satan, are in reality servants of the King. This makes sense of Jesus’s command to Judas (“do quickly” [ποίησον τάχιον]).

13:28 But no one among those reclining understood why he said this to him (τοῦτο [δὲ] οὐδεὶς ἔγνω τῶν ἀνακειμένων πρὸς τί εἶπεν αὐτῷ). The cosmological insight provided to the reader by the narrator is now contrasted with the rest of the disciples who were watching the symbol-laden interaction between Jesus and Judas. The narrator explains that “no one . . . understood” (οὐδεὶς ἔγνω) the statement Jesus made to Judas. With no awareness of the wordless signal of the dipping of the piece of bread, the disciples appear to be looking for the meaning of Jesus’s stated words alone. In this pericope, wordless communication has played a significant role in the narrative. This is true once again here by the narrator’s description of the rest of the disciples as “those reclining” (τῶν ἀνακειμένων), a symbolic depiction of their intimate relationship to Jesus.

13:29 For some were thinking, since Judas was holding the money box, that Jesus said to him, “Buy what we need for the Feast,” or [spoke to him] in order that he might give something to the poor (τινὲς γὰρ ἐδόκουν, ἐπεὶ τὸ γλωσσόκομον εἶχεν Ἰούδας, ὅτι λέγει αὐτῷ [ὁ] Ἰησοῦς, Ἀγόρασον ὧν χρείαν ἔχομεν εἰς τὴν ἑορτήν, ἢ τοῖς πτωχοῖς ἵνα τι δῷ). The narrator does not merely note the misunderstanding of the disciples but even offers a description of the innocent constructions they concocted to explain the departure of Judas, who had previously been “among those reclining” (v. 28). The disciples knew Judas was the administrator of the common fund (see 12:6), so they assumed by implication that Jesus either told him to purchase what was needed for the Passover Feast or instructed him regarding a religious offering for the poor, which was common during such festivals (cf. Tob 2:2).

13:30 Then after he took the piece of bread, he went out immediately; and it was night (λαβὼν οὖν τὸ ψωμίον ἐκεῖνος ἐξῆλθεν εὐθύς· ἦν δὲ νύξ). The pericope concludes with the departure of Judas from the intimate communion of Jesus and his disciples. It is of great significance that the narrator again, continuing the theme of “wordless” signals, connects the departure of Judas with the giving of the piece of bread (cf. v. 27). The narrative could not express in more physical (action-based and symbol-laden) terms the contrast between the intimate communion and the betrayal.

Judas physically removes himself from the communion, with the narrative giving it emphasis with the adverb “immediately” (εὐθύς). This departure is hardly just a depiction of the historical plot—that Judas left the room—but also of the cosmological plot of the Gospel, that Judas left the “one flock” and the “one Shepherd” (see 10:16). It is with this in mind that the narrator’s concluding description must be understood: “And it was night” (ἦν δὲ νύξ). Without denying that this detail fits nicely with the time of day at which the meal was taking place, the term “night” is never used positively in the Gospel (cf. 3:2; 11:10; 21:3) and impresses upon the reader the symbolic, cosmological realities at play in the action of the Gospel. Even the “night” serves as a “wordless” communication to the reader!

It is important to note that the exit by Judas at v. 30 is part of the “dynamic movement” of the Gospel’s farewell discourse, serving as a transitional marker and bringing closure to its two-part introduction (see comments before 13:1). According to Parsenios, an important detail to note from this dramatic exit is that Judas does not leave the meal of his own accord. It is a “forced” exit; Jesus orders Judas to exit. This plot-guiding insight serves two significant functions.18 First, such an exit sends someone offstage to prepare for future action. In order for Jesus properly to address “his” disciples, Judas the outsider needed to leave. The plot depended on this symbolic action. Second, involuntary (or “forced”) exits remove from the scene a character whose presence would disrupt its natural flow. The reader is, in a sense, readjusted or better prepared for what is about to come (the farewell discourse proper). The significance of this will be made clear at the beginning of the next pericope (see comments on 13:31).

Theology in Application

Jesus gathers his disciples together, washes their feet in a ceremony filled with symbolism of service and sacrifice (the cross), and then prophecies that he is about to be betrayed by one of them! The betrayal reveals not merely who is with Jesus (the “Eleven”) but also who is against him—not merely Judas but Satan himself. As the second of a two-part introduction to the farewell discourse, this pericope gives the reader a powerful depiction of the call of discipleship and the demands facing Jesus, not only the external opposition of the prince of darkness, but also the internal opposition from one of “his own” (1:11). Through this pericope the reader witnesses both the historical and cosmological forces at work in the world and is exhorted to be faithful to the end, resting comfortably in the love and on the “chest” of Jesus.

Body (of Christ) Language

This pericope communicates its message with an abundance of nonverbal, symbol-laden actions and gestures that present a robust portrait of the body of Christ. The foot washing of the previous pericope (13:1–20) offered one significant symbol-laden act, but this pericope is filled with small, almost unnoticeable acts that communicate rich theological realities. The “look” between disciples (v. 22) and the “nod” Peter gives to the Beloved Disciple (v. 24) communicate a shared identity and cause and express a trust and fellowship that words alone cannot depict. Moreover, the description of the disciples “reclining” together (v. 28) and sharing in a meal together, which included Judas (vv. 26, 27, 30), portrays the intimate fellowship of the disciples of the new covenant, with whom God himself was “dwelling” (1:14).

The church, the people of God, can and must speak with words; the saying, “Preach the gospel, and if necessary use words,” is even at its best incomplete, for the gospel is a message that requires words. Yet the truth of the gospel begets a way of life that also speaks. Such “wordless” communication shows the way brothers and sisters in Christ live and work together, trust and share together. They are expressions of the very nature of the Trinitarian God.

The Beloved Disciple

The first appearance of the Beloved Disciple depicts him as an “ideal disciple,” having immediate access to and intimate closeness with Christ. It takes all of the apostle Paul’s robust theology regarding life “in Christ” to serve as a commentary on the symbolic description of the Beloved Disciple leaning “on the chest of Christ” (v. 25). It should be no surprise that John in his first letter calls the church “the beloved” (Ἀγαπητοί), a term that is minimized by its translation as “dear friends” (NIV; see 1 John 2:7). The Beloved Disciple enjoyed an intimate relationship with the Lord, but so do all disciples have such a relationship with the Lord. God is the lover and we are the loved. The same God who loves the whole world (3:16) simultaneously declares his love to each Christian that each is his “beloved” disciple.

Satan

This is the only pericope in the Gospel that mentions Satan by name. But befitting the cosmological plot of the Fourth Gospel, Satan is a primary character of the darkness, which was introduced to the reader in the prologue (1:5). “Darkness” is abstract; “Satan” is what Scripture uses to express its personal nature. Paul explains this well, “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly [i.e., cosmological] realms” (Eph 6:12). Paul and John together teach that Satan opposes Christ and therefore those who belong to Christ. Moreover, Satan is not far removed from the people of God but beside them and, when permitted, “in” them (v. 27). The purpose of this pericope is not to give a full description of Satan but to show how present and active is the darkness. But thanks be to God, the light shines in the darkness (1:5).

Judas and the Christian

Judas must not be viewed as an isolated example but as a common experience in the church. While the gospel is good news, it is not easily swallowed. Scripture warns that the message of Christ is a stumbling block and foolishness (1 Cor 1:23) and that even Satan, “the god of this age,” is actively blinding the minds of the world (2 Cor 4:4). But as scary as this is, there is something else frightening in the example of Judas. Judas does not represent disbelief among those on the outside of faith and opposed to Christ but disbelief among the faithful and those on the inside. Judas is a far more threatening figure than Pilate or the Jewish leaders, for he reminds us that on any day some faithful follower sitting among us might turn off the light and stumble out into the darkness.19

May this not be you, O reader of this Gospel. May the Spirit of God protect you from such a flight into the “night,” into darkness and keep you in Christ, “shielded by God’s power” (1 Pet 1:5), in intimate communion with Christ. Hold firm, Christian; hold fast, church.