Chapter 1

Your Business in Context

IN THIS CHAPTER

Analyzing the feasibility of your business idea

Analyzing the feasibility of your business idea

Figuring out your industry

Figuring out your industry

Doing research on your industry

Doing research on your industry

Determining where you fit in

Determining where you fit in

Targeting a new product for the market

Targeting a new product for the market

This chapter starts at the very beginning, looking at how to step back and see a potential start-up business in the context within which it operates. If you’ve already started your business and are committed to it, or if you know exactly what kind of business you want to run and nothing will change your mind, or if your idea is to start rather small, with a modest idea that doesn’t require finding much funding to get you going, you can skip this chapter. Good luck to you.

But it could be to your advantage to stick around anyway, because the fact is, not every business is a good idea at the time and place where it is born. You could save yourself some heartache by examining the external factors that will affect your business whether you like it or not. If you choose the right business at the right time and the right place, your chances of success are much higher.

Every successful business operates inside an environment that affects everything it does. The environment includes the industry in which the business operates, the market the business serves, the state of the economy, and the various people and businesses the business interacts with. Your business doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Now, more than ever before, understanding your industry is a critical component of your business venture’s success.

If you position your company well inside a growing, healthy industry, you have a better chance of building a successful venture. By contrast, if your business niche is a weak position in a hostile, mature industry, your fledgling business may be doomed. Conducting a feasibility analysis can be a good way to get a clear picture of the landscape. The first section of this chapter provides an overview of this process.

An Overview of Feasibility Analysis

A feasibility analysis consists of a series of tests that you conduct as you discover more and more about your opportunity. After each test, you ask yourself whether you still want to go forward. Is there anything here that prevents you from going forward with this business? Feasibility is a process of discovery, and during that process you will probably modify your original concept several times until you get it right. That’s the real value of feasibility — the way that it helps you refine your concept so that you have the highest potential for success when you launch your business.

Today, you can often go for financing on the strength of a feasibility study alone. Certainly in the case of Internet businesses, speed is of the essence. Many an online business has gotten first-round financing on its proof of concept alone and then done a business plan before going for bigger dollars in the form of venture capital. But even if your business is a traditional one, feasibility can help you avoid big early mistakes.

Executive summary

The most important information to emphasize in the executive summary is your proof that customers want what you have to offer. This proof comes from the primary research you do with the customers to find out what they think of your concept and how much demand there is. The other key piece to emphasize is your description of your founding team. Even the greatest ideas can’t happen without a great team, and investors put a lot of stock in a founding team’s expertise and experience.

Business concept

- What is the business?

- Who is the customer?

- What is the value proposition?

- How will the benefit be delivered?

It’s important to be able to state your business concept in a few clear, concise, and direct sentences that include all four of the components of the concept. This is what is often called your elevator pitch — a conversation that begins when the elevator door closes and ends when the door opens at your floor. That means you have only a few seconds to capture your listener’s attention, so you better be able to get it all out quickly and confidently. If you’re preparing a feasibility analysis that will be shown to investors, you should state your business concept right up front in the concept section. Then you can elaborate on each point as a follow-up. Here’s an example:

Rural Power Tools is in the power equipment business, providing contractors and developers solutions to power needs in remote areas through rental equipment outlets.

As you find out more about your business concept, you’ll also want to consider the various spin-off products and services you may be able to offer.

Industry analysis

Testing whether or not the industry in which you will be operating will support your concept is an important part of any feasibility analysis. Here you look at the status of your industry, identify trends and patterns of change, and look at who the players in terms of competitors may be. Also, don’t forget that one way to find a great opportunity is to study an industry first. More details on how to do an industry analysis are covered in the section “Researching an Industry,” later in this chapter.

Market/customer analysis

Here you will be testing your customer. Ideally, inside your industry, you find a market segment appropriate to your business. Then you identify a niche that is not being served so that you have an entry strategy with the lowest barriers possible and the highest probability of success. In this part of the analysis, you also look at what your potential customer wants and what the demand for your product/service is. You will also consider a variety of different distribution channels to deliver the benefit to the customer. To find out more, see the section “Defining Your Market Niche,” later in this chapter.

Genesis or founding team analysis

Investors look very carefully at the founding team because even the best concept won’t happen without a team that can execute it. In this part of the analysis, you want to consider the qualifications, expertise, and experience of your founding team, even if that consists of only yourself. Be aware that today’s business environment is so complex and fast-paced that no one person has all the skills, time, and resources to do everything him- or herself.

Product/service development analysis

Whether you’re planning to offer a product or a service or both (and that’s usually the case), it’s going to take some planning. Consider which tasks must be accomplished to prepare the product or service for market, whether that is developing a product from raw materials and going through the patent process or developing a plan for implementing a service concept. Identify these preparatory tasks and figure out a realistic timeline for completion of them. Put that timeline in your analysis.

Financial analysis

In this part of the feasibility analysis, you figure out how much money you need to start the business and carry it to a positive cash flow. You also distinguish among the types of money, which will be important in defining your financial strategy. You can find out more about finding funding in Chapter 2 of Book 2.

Feasibility decision

After you have gone through all the various tests that comprise the feasibility analysis, you are ready to make a decision about going forward. Of course, throughout the process of doing the tests, you may have decided to stop — because of something you found out from analysis of the industry, market, product/service, and so forth. But if you’re still on the mission, now’s the time to define the conditions under which you go forward.

Timeline to launch

You always need to end a feasibility analysis with an action plan so that you’re sure that at least something will happen. Establishing a list of all tasks to be completed and a time frame for completing them will increase the probability that your business will be launched in a timely fashion. The research you have done along the way will help you make wise decisions about the length of time it takes to complete everything and open the doors to your business.

Understanding Your Industry

New industries emerge on a regular basis. In fact, with e-commerce holding so much of the attention of young businesspeople today, you may well ask, “Is e-commerce an industry?” That’s a great question. If you define an industry as a group of related businesses, then all e-commerce businesses have one thing in common: the Internet. But retail businesses, manufacturers, wholesalers, and service companies are all on the Internet, so every member of the value chain is found in one location.

All retail businesses have retail in common, and all manufacturers have manufacturing in common. Are retail and manufacturing industries as well? Within retail, you find clothing retailers and book retailers among many others. Is clothing an industry? Is publishing an industry? The answer to all these questions is yes.

Actually, there are layers of industries, starting with the broadest terms and working down to the more specific terms. Take an e-commerce business that almost everyone knows: Amazon.com. If you consider e-commerce to be an industry, a grouping of like businesses, then Amazon is definitely part of that industry. Within e-commerce, Amazon is also a retail business that happens to be using the Internet as its marketing/distribution channel. Within retail, it operates in the publishing, music, toys, and video industries, among others. What this means to you is that when you study Amazon’s industry, you’re really looking at multiple distinct industries, and it’s important to understand what’s going on in each.

Using a framework of industry structure

One way to begin to look at the industry you’re interested in is to use a common framework. One useful framework is based on the work of W.H. Starbuck and Michael E. Porter, two experts on organizational strategy. This framework steps you through analyzing your potential industry by assessing the outside forces that work upon it and then assessing the countermeasures that you’ll need to implement against those outside forces. According to Starbuck and Porter, new businesses must be constantly on the lookout for forces that affect them in every area.

The business environment, especially the entrepreneurial environment, often looks like a battlefield. But for every threat there’s a countermeasure. The first step is to look at what these outside forces really are.

Carrying capacity, uncertainty, and complexity

This first environmental factor explains why so many industries today are changing, moving more rapidly, and making it more difficult for businesses to succeed. Carrying capacity refers to the extent to which an industry can accept more businesses. Industries can become oversaturated with too many businesses. When that happens, the capacity of businesses to produce their products and services exceeds the demand for them. Then it becomes increasingly difficult for new businesses to enter the industry and survive.

Uncertainty refers to the predictability or unpredictability of the industry — stability or instability. Typically volatile and fast-changing, modern technology industries produce more uncertainty. But these same industries often produce more opportunities for new businesses to take advantage of.

Complexity is about the number and diversity of inputs and outputs in the industry. Complex industries cause businesses to have to deal with more suppliers, customers, and competitors than other industries. Biotechnology and telecommunications are examples of industries with high degrees of complexity in the form of competition and government regulation.

Recognizing threat to new entrants

Some industries have barriers to entry that are quite high. These barriers come in many forms. Here are the main ones:

- Economies of scale: These are product volumes that enable established businesses to produce goods more inexpensively than a new business can. A new business can’t compete with the low costs of the entrenched firms. To combat economies of scale, new firms often form alliances that give them more clout.

- Brand loyalty: If you’re a new business, you face competitors that have achieved brand loyalty, which makes it much more difficult to entice customers to your products and services. That’s why it’s so important to find a market niche that you can control — a need in the market that is not being served. That will give you time to establish some brand loyalty of your own. Later in this chapter you find out more about niches, and Chapter 4 in Book 5 covers branding in detail.

- High capital requirements: In some industries, you encounter high costs for the advertising, R&D (research and development), and plants and equipment you need to compete with established firms. Again, new companies often overcome this barrier by outsourcing expensive functions to other firms.

- Buyer switching costs: Buyers don’t generally like to switch from one supplier to another unless there’s a good reason to do so. That’s why once a person invests the time to learn and use the Windows environment, for example, he or she is reluctant to start all over with a different platform. Entrepreneurs must match a need that is not being met with the current product on the market to get the customer to switch.

- Access to distribution channels: Every industry has established methods for getting products to customers. New companies must have access to those distribution channels if they are going to succeed. The one exception is where the new business finds a new method of delivering a product or service that the customer accepts — for example, the Internet.

- Proprietary factors: Established companies may own technology or a location that gives them a competitive advantage over new companies. However, new ventures have often entered industries with their own proprietary factors that enable them to enjoy a relatively competition-free environment for a brief time.

- Government regulations: In some industries, a long and expensive governmental process, such as FDA approval for foods and drugs, can be prohibitive for a new business. That’s why many new ventures form strategic alliances with larger companies to help support the costs along the way.

- Industry hostility: In some industries, rival companies make it difficult for a new business to enter. Because they typically are mature companies with many resources, they can afford to do what it takes to push the new entrant out. Again, finding that niche in the market where you’re giving the customer what your competitors are not helps your company survive, even in a hostile industry.

Identifying threat from substitute products/services

Remember that your competition comes not only from companies that deal in the same products and services that you do, but also from companies that have substitute products. These products accomplish the same function but use a different method. For example, restaurants compete with other restaurants for consumer dollars, but they also compete with other forms of entertainment that include food. You could go out to dinner at a restaurant, take in a movie, and stop off at a pub for a nightcap. But there are movie theaters now where you can do all three of these things.

Spotting threat from buyers’ bargaining power

Buyers have the power to force down prices in the industry when they are able to buy in volume. Established companies, if they are worth their salt, have this kind of buying power. New entrants can’t purchase at volume rates; therefore, they have to charge customers more. Consequently, it’s more difficult for them to compete.

Distinguishing threat from suppliers’ bargaining power

In some industries, suppliers have the power to raise prices or change the quality of products that they supply to manufacturers or distributors. This is particularly true where there are few suppliers relative to the size of the industry and they are the primary source of materials in the industry. Don’t forget that labor is also a source of supply, and in some industries such as software, highly skilled labor is in short supply; therefore the price goes up.

Being aware of rivalry among existing firms

Highly competitive industries force prices down and profits as well. That’s when you see price wars, the kind you find in the airline industry. One company lowers its prices and others quickly follow. This kind of strategy hurts everyone in the industry and makes it nearly impossible for a new entrant to compete on price. Instead, savvy new businesses find an unserved niche in the market where they don’t have to compete on price.

Deciding on an entry strategy

The structure of your industry will largely determine how you enter it. Failing to consider the structure of your industry can mean that you spend a lot of time and money only to find that you have chosen the wrong entry strategy. By then, you may have lost your window of opportunity. For the most part, new ventures have three broad options as entry strategies: differentiation, niche strategy, and cost superiority.

- Differentiation: With a differentiation strategy, you attempt to distinguish your company from others in the industry through product/process innovation, a unique marketing or distribution strategy, or through branding. If you are able to gain customer loyalty through your differentiation strategy, you will succeed in making your product or service less sensitive to price because customers will perceive the inherent value of dealing with your company.

- Niche strategy: The niche strategy is perhaps the most popular strategy for new ventures. It involves identifying and creating a place in the market where no one else is — serving a need that no one else is serving. This niche gives you space and time to compete without going head to head with the established players in the industry. It lets you own a piece of the market where you can establish the standards and create your brand.

- Cost superiority: Being the low-cost leader is typically difficult for a new venture because it relies heavily on volume sales and low-cost production. A new venture can take advantage of providing the lowest-cost products and services when it’s part of an emerging industry where everyone shares the same disadvantage.

Researching an Industry

Getting to understand your industry inside and out is critical to developing any business strategies you may have. Yes, it’s a lot of work, but it will pay off many times over.

- Ask yourself whether the site or author is a recognized expert in the field.

- Ask people who are familiar with the industry you’re researching whether they’ve ever heard of that site or that person.

- Compare what that site or person has said with what others are saying. If you find a number of sources that seem to agree, you’re probably okay. Of course, don’t assume that just because many people are saying something, it’s necessarily true — that’s how rumors get started.

Checking out the status of your industry

- Is the industry growing? Growth can be measured in many ways: number of employees, revenues, units produced, and number of new companies entering the industry.

- Who are the major competitors? You want to understand which companies dominate the industry, what their strategies are, and how your business is differentiated from them.

- Where are the opportunities in the industry? In some industries, new products and services provide more opportunity, whereas in others, an innovative marketing and distribution strategy will win the game.

- What are the trends and patterns of change in your industry? You want to look backward and forward to study what has happened over time in your industry to see if it foreshadows what will happen in the future. You also want to see what the industry prognosticators are saying about the future of the industry. But the best way to find out about the future of your industry is to get close to the new technology that is in the works yet may not hit the marketplace for five years.

- What is the status of new technology and R&D spending? Does your industry adopt new technology quickly? Is your industry technology-based or driven by new technology? If you look at how much the major firms are spending on research and development of new technologies, you’ll get a pretty good idea of how important technology is to your industry. You’ll also find out how rapid the product development cycle is, which tells you how fast you’ll have to be to compete.

- Are there young and successful companies in the industry? If you see no new companies being formed in your industry, it’s a pretty good bet that it’s a mature industry with dominant players. That doesn’t automatically preclude your entry into the industry, but it does make it much more expensive and difficult.

- Are there any threats to the industry? Is there anything on the horizon that you or others can see that makes any part of your industry obsolete? Certainly, if you were in the mechanical office equipment industry in the early 1980s, you should have seen the writing on the wall with the introduction and mass acceptance of the personal computer.

- What are the typical gross profit margins in the industry? The gross profit margin (or gross margin) tells you how much room you have to make mistakes. Gross margin is the gross profit (revenues minus cost of goods sold) as a percentage of sales. If your industry has margins of 2 percent, like the grocery industry has (sometimes even less), you have little room for error, because 98 percent of what you receive in revenues goes to pay your direct costs of production. You only have 2 percent left to pay overhead. On the other hand, in some industries gross margins run at 70 percent or more, so you end up with a lot more capital to expend on overhead and profit.

Competitive intelligence: Checking out the competition

One of the most difficult tasks you’ll face is finding information about your competitors. Not the obvious things that you can easily find by going to a competitor’s physical site or website (although of course you should do those things), but the really important stuff that can affect what you do with your business concept. Things like how much competitors spend on customer service, what their profit margins are, how many customers they have, what their growth strategies are, and so forth.

If you’re in competition with private companies (which is true most of the time), your task is that much more difficult because private companies don’t have to disclose the kinds of information that public companies do.

Here’s some of the information you may want to collect on your competitors:

- The management style of the company

- Current market strategies — also what they’ve done in the past because history tends to repeat itself

- The unique features and benefits of the products and services they offer

- Their pricing strategy

- Their customer mix

- Their promotional mix

With a concerted effort and a plan in hand, you can find out a lot about the companies you’ll be competing against. This section provides a step-by-step strategy for attacking the challenge of competitive intelligence.

Pound the pavement

If your competition has bricks-and-mortar sites, visit them and observe what goes on. What kinds of customers frequent their sites? What do they buy, and how much do they buy? What is the appearance of the site? How would you evaluate the location? Gather as much information as you can through observation and talking to customers and employees.

Buy your competitors’ products

Buying your competitors’ products helps you find out more about how your competition treats its customers and how good its products and services are. If you think that it sounds strange to buy your competitors’ products, just remember, as soon as yours are in the marketplace, your competitors will buy them.

Rev up the search engines

Go to the Internet and hit the search engines. Just type in the names of the companies you’re interested in and see what comes up. True, this is not the most effective way to search, but it’s a start, and you never know what you’ll pull up that you otherwise may not have found.

Check information on public companies

- D&B Hoovers (

www.hoovers.com): This source provides detailed profiles of public companies. Visit the site to find out about current pricing. - U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (

www.sec.gov): This site contains the SEC’s EDGAR (Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval) database about companies. It’s not terribly user friendly but has great information. Try Free Edgar,www.freeedgar.com, which is a good place to research public companies and those that have filed to go public.

Use online media

Here are some great online sources that you may want to check out:

- Inc. (

www.inc.com): This database of the fastest-growing private companies in the U.S. contains information you won’t find elsewhere on revenue, profit-and-loss percentages, numbers of employees, and so forth for the past eight years. - Fuld + Company (

www.fuld.com): This site gives you advice on how to seek competitive intelligence and has many links to information on specific industries. - ProfNet (

www.profnet.com): This site provides a direct link to experts at universities, colleges, corporations, and national laboratories. You may be able to find an expert in your industry and contact that person. Check the site for current pricing. - ProQuest eLibrary (

www.elibrary.com): This is a great site if you’re looking for articles, reference works, and news wires. You can request a free trial; check the site for current pricing. If you’re near a local university, you may be able to access it from the university’s library computers.

Look for data at government websites

You can find an extensive network of government sites with mostly free information on economic news, export information, legislative trends, and so forth. You may want to go directly to often-used sites like the following:

- U.S. Department of Commerce (

www.commerce.gov): Here you’ll find everything you ever wanted to know about the U.S. economy. - U.S. Census Bureau (

www.census.gov): This is the home of the stats based on the census taken every ten years. The amount of information available here is very impressive. - Bureau of Labor Statistics (

www.bls.gov): This is another site full of information on the economy, in particular, the labor market.

Go off-line for more research

The Internet is not the only place you can find important information. Here are two off-line options you ought to consider:

- Industry trade associations: Virtually every industry has its own trade association with a corresponding journal or magazine. Trade associations usually track what’s going on in their industries, so they are a wealth of information. If you are serious about starting a business in your particular industry, you may want to join a trade association, so you’ll have access to inside information.

- Network, network, network: Take every opportunity to talk with people in the industry. They are on the front lines on a daily basis and they will give you information that is probably more current than what you’ll find in the media or on the web.

Defining Your Market Niche

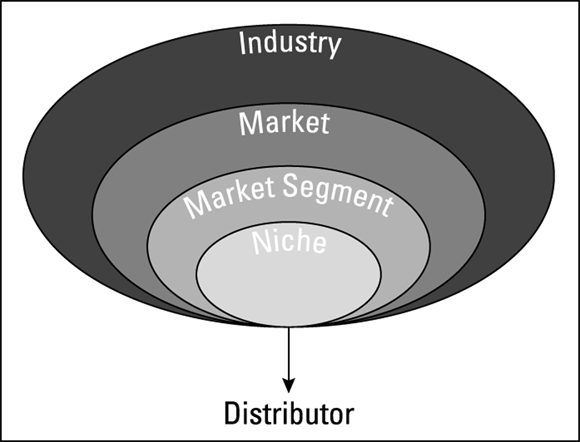

Markets are groups of customers inside an industry. Take a look at Figure 1-1 and you can see that in conducting your feasibility analysis (covered earlier in this chapter), you work your way down from the broad industry to the narrower market niche.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 1-1: Finding your niche.

Narrowing your market

Within each broad market are segments. For example, the broad market of people who buy books contains segments of customers for

- Travel books (or any other broad category of books)

- Kids’ books

- Books appealing to seniors

- Audiobooks

Within a market segment, you can find niches — specific needs that perhaps aren’t being served — such as

- Travel books geared toward people with disabilities

- Kids’ books that target minorities

- Books that teach seniors how to deal with technology

- Audiobooks that provide current journal articles to professionals

Market niches provide a place for new businesses to enter a market and gain a foothold before bigger companies take notice and begin to compete. Having a niche all to yourself gives you a quiet period during which you alone serve a need of the customer that otherwise is not being met. As a result, you get to set the standards for the niche. In short, you’re the market leader.

Defining your target market is about identifying the primary customer for your products or services — the customer most likely to purchase from you. You want to identify a target market because creating customer awareness of a new product or service is time-consuming and costly, requiring lots of marketing dollars — dollars that few start-ups have at their disposal. So, instead of using a shotgun approach and trying to bag a broad market, aiming at the specific customers who are likely to purchase from you is far more effective. More important still, going to the customer who’s easiest to sell to helps you gain a foothold quickly and start to build brand recognition, which makes selling to other potential customers easier.

Your first definition of a target customer will probably be fairly loose — an estimate. For example, suppose you target customers are “professional women.” That’s a fairly broad estimate. But as you conduct market research, you come to know your primary customer well. In this example, the picture may emerge of “a woman in law, medicine, or business, between 35 and 55 years of age, married, with children.”

The basic questions to answer about your potential customers are:

- What are their demographics: Age, education, ethnicity, income level?

- What are their buying habits? What do they buy? When? How?

- How do customers hear about your products and services? Do your customers buy based on TV ads, magazines, social media, web advertising, word-of-mouth, referrals?

- How can your new business meet customers’ needs? What customer need is your product now meeting?

Where do you find the answers to these important questions? Your market research — actually talking with potential customers — provides answers.

Don’t forget that if your customer is another business, that business may not be the actual end user of your product or service. So then you also have an end user to deal with. The end user is the ultimate consumer, the person who uses the product or service. For example, here is a typical channel for distributing a product:

Manufacturer > Distributor > Retailer > Consumer

If that distribution channel is filled with your products — refrigerators, for example — who is your customer? It’s the distributor who purchases the fridge from you to distribute to retailers. The retailer, in turn, is the distributor’s customer. The consumer, who actually uses the fridge, is the retailer’s customer and your end user. (The easiest way to identify the customer is to find out who pays you — follow the money.)

Developing a niche strategy

One primary reason to define and analyze a target market is to find a way into the market so that you have a chance to compete. If you enter a market without a strategy, you’re setting yourself up for failure. You are the new kid on the block. If customers can’t distinguish you from your competitors, they’re not likely to buy from you. People generally prefer to deal with someone they know.

Niche strategy is probably the premier strategy for entrepreneurs because it yields the greatest amount of control. Creating a niche that no one else is serving is the key. That way, you become the leader and can set the standards for those who follow. Niche strategy is important because, as the sole occupant of the niche, you can establish your business in a relatively safe environment (the quiet period) before you develop any direct competitors. Fending off competitors takes a lot of marketing dollars, and when you’re a start-up company, you have numerous better uses for your limited resources.

How do you find a niche that no one else has found? By talking to customers. The target market from which your business opportunity comes also holds the keys to your entry strategy. Your potential customers tell you what’s missing in your competitors’ products and services. They also tell you what they need. Fulfilling that unmet need is your entry strategy.

Zeroing In on a Brand-New Product

Many entrepreneurs would like to deal in products, but they’re not quite sure how to get started. Of course, you could import products from other countries or buy your products from domestic manufacturers. But if you like the idea of manufacturing and distributing a brand-new technology or other type of product, then you have three choices: invent something, team up with an inventor, or license an invention.

Become an inventor

If you’re the kind of person who likes to tinker and play around with new ideas that might become inventions, then your role might be to invent a new product. Most entrepreneurs and start-up businesspeople, however, are not inventors — not because they don’t have the ability to invent, but because their focus is elsewhere.

The mindsets of businesspeople and inventors tend to be quite different, and it’s unusual to find both in the same person. Not only are the mindsets different, but the skills required by each are very different. In general, pure inventor types aren’t interested in the commercial side of things. They invent for the love of invention. Unless an entrepreneur comes along and points out an opportunity, many inventors never see their inventions reach the marketplace.

Team up with an inventor

Entrepreneurs often team up with inventors to commercialize a new product. Often the opportunity to pair up with an inventor comes out of the industry in which you’re working. You hear about someone who’s working on something; you investigate and discover an interesting invention.

Don’t hesitate to approach an inventor, but remember a couple important things:

- Inventors are paranoid about their inventions. They are sure that someone is out to steal their ideas.

- Inventors typically aren’t business oriented and don’t want to become business people. Their love is inventing, so don’t expect them to be partners in a business sense.

License an invention

Companies, universities, the government, and independent inventors are all looking for entrepreneurs to commercialize their inventions. You gain access to these inventions through a vehicle known as licensing. Licensing grants you the right to use the invention in an agreed-upon way for an agreed-upon time period. In return, you agree to pay a royalty to the inventor, usually based on sales of the product that results from the invention.

The executive summary is probably the most important piece of a feasibility analysis because, in two pages, it presents the most important and persuasive points from every test you did during your analysis. An effective executive summary captures the reader’s attention immediately with the excitement of the concept. It doesn’t let the reader get away; it draws the reader deeper and deeper into the concept as it proves your claim that the concept is feasible and will be a market success.

The executive summary is probably the most important piece of a feasibility analysis because, in two pages, it presents the most important and persuasive points from every test you did during your analysis. An effective executive summary captures the reader’s attention immediately with the excitement of the concept. It doesn’t let the reader get away; it draws the reader deeper and deeper into the concept as it proves your claim that the concept is feasible and will be a market success. For an online business, you may want to prepare what’s called a proof of concept. This is essentially a one-page statement of why your concept will work, emphasizing what you have done to prove that customers will come to your site. That may be in the form of showing hits to your beta site or a list of customers signed up and ready to go when the site is finished. Similarly, if you’re developing a new product, your proof of concept is your market-quality prototype.

For an online business, you may want to prepare what’s called a proof of concept. This is essentially a one-page statement of why your concept will work, emphasizing what you have done to prove that customers will come to your site. That may be in the form of showing hits to your beta site or a list of customers signed up and ready to go when the site is finished. Similarly, if you’re developing a new product, your proof of concept is your market-quality prototype. One-product businesses often have a more difficult time becoming successful than multi-product/service companies. You don’t want to put all your eggs into one basket if you can help it, and you want to give your customer choices.

One-product businesses often have a more difficult time becoming successful than multi-product/service companies. You don’t want to put all your eggs into one basket if you can help it, and you want to give your customer choices.