Chapter 4

Finding Your Target Market

IN THIS CHAPTER

Taking stock of the target market

Taking stock of the target market

Picking the right industry

Picking the right industry

Getting the niche right

Getting the niche right

Gauging the most attractive customers

Gauging the most attractive customers

Choosing the best spot on the industry value chain

Choosing the best spot on the industry value chain

The most important step toward creating a great business is creating a product or service that customers want and will buy. This is called a powerful offering. The first step in creating a powerful offering is selecting the right market. Picking the proper combination of industry attractiveness, niche attractiveness, and customer attractiveness creates the best market for your product.

Gauging the Target Market

You should find a profitable and sufficiently large market segment. However, in order to have a successful and durable business, you need to find a large market that’s unserved or underserved. Finding this underserved market is paramount.

Anyone can find huge markets to attack. Hey, let’s sell coffee! The market is large and growing, right? However, several large and successful companies already own pieces of this market. In general, it’s unwise to attack an established competitor in the exact same market segment. Traditionally, the first mover or incumbent wins.

- How attractive is the industry itself? For instance, software companies tend to be more profitable than construction companies. Professor Scott A. Shane conducted research for his book The Illusions of Entrepreneurship: The Costly Myths That Entrepreneurs, Investors, and Policy Makers Live By (Yale University Press). That research offers significant data that some industries are more viable and profitable than others. Of course, other areas of the business model have great effect on the overall profitability.

- How attractive is the niche within the industry? Typically, packaged software developers are more profitable than custom software developers. You want to pick a niche that offers the best potential profitability.

- How attractive is the customer segment? The high-end customer targeted by Starbucks is more profitable than the customer targeted by McDonald’s. An attractive customer doesn’t have to be a wealthy customer. An attractive customer is the one who can make your business model work best. For instance, many profitable business models are being created for the unbanked (people without checking accounts). See Chapter 3 in Book 1 for an introduction to business models.

- Is the niche big enough to provide a good opportunity for you to enter it and sell enough product or services, at a price point that will allow you to create a viable business? Prosthetic limbs for pet dogs may seem like a great idea, but can you sell enough of them at a high enough price to be able to make any money doing it?

Determining Industry Attractiveness

An industry is the broadest category or definition of the business you’ll be in. Examples of industry include the following:

- Automotive aftermarket manufacturing

- Business consulting

- General contracting

- Home remodeling

- Lawn and garden distribution

- Legal services

- Medical

- Pet care

- Residential landscaping

- Software development

Within a broad industry are often-defined industry segments that further refine the offering. Here are some examples:

- The vehicle manufacturing industry has segments for heavy-duty trucks, electric automobiles, recreational vehicles, and more.

- The restaurant industry has segments for fast food, fine dining, casual dining, and so on.

- Clothing manufacturers have segments for athletic wear, men’s suits, lingerie, women’s business attire, and bridal gowns, among others.

- The medical doctor industry has segmentation for general practitioners, surgeons, podiatrists, holistic practitioners, ophthalmologists, and hundreds more.

- The HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) industry has segments for light-duty, boilers, and heavy-duty systems.

You’re much more likely to be successful in a “good” industry than a “bad” one. In a good industry, most companies are successful; examples include software development, mineral extraction, and insurance. In a bad industry, margins are historically low and/or competition is overly intense; examples include airlines and construction. However, you can find numerous examples of companies that entered unattractive industries and were successful because their business model was strong in other areas. Examples include Waste Management (garbage), Apple (computer hardware), Nike (shoes), and Vistaprint (commercial printing).

- Is this industry, as a whole, growing or shrinking?

- Will this industry be strong in ten years?

- How many incumbents are in this industry, and how strong are they?

- Do you see an opportunity for this industry to overlap into a different existing market (convergence)?

- Could the industry provide powerful synergies with an existing part of your business?

Book 1, Chapter 1 talks more about researching your chosen industry.

After you identify an attractive industry, you identify the best subset of that market, or niche, and then identify the best customers to serve within that niche. Working in an attractive industry is helpful, but it isn’t a prerequisite. Many great business models have been created in bad industries by carving out attractive customer segments, niches, or both.

For example, Vistaprint created an excellent business model serving customers no one wanted (microbusinesses) in an industry no one wanted to be in (printing). Vistaprint succeeded by leveraging a highly differentiated sales, distribution, and cost model.

There’s an old saying: “Everyone thinks they know how to run a restaurant because they know how to eat.” Every industry and business can be learned. However, if you’re unfamiliar with an industry, count on some hard work to get up to speed.

Finding the best industry

Picking an attractive industry for your business model may seem simple. The key lies in research (see Book 1, Chapter 1 for more ideas on how to conduct your research). One thing you should do is gather as much independent information as possible regarding current and future trends. By doing so, you’re able to make the best choice of industry for your model. Here are some places to find industry data and trends:

- Paid services such as Gartner (

www.gartner.com) and Forrester Research (www.forrester.com) - General business publications and news outlets like Bloomberg Businessweek (

www.businessweek.com), Inc. (www.inc.com), Barron’s (www.barrons.com), and CNN Business (http://money.cnn.com) - Books

Industry trade publications

Watch out for bias when using trade publications as a resource. Such publications put the most positive spin on the industry. For instance, travel industry trade publications were likely still positive on the industry in 2000 even though Internet sites like Priceline.com and Expedia.com were beginning to destroy portions of the business.

Watch out for bias when using trade publications as a resource. Such publications put the most positive spin on the industry. For instance, travel industry trade publications were likely still positive on the industry in 2000 even though Internet sites like Priceline.com and Expedia.com were beginning to destroy portions of the business.- Industry associations

- Personal experience

- The IRS or state government (look for the number of businesses in an industry starting or filing bankruptcy)

Working in unserved or underserved markets

Unserved or underserved markets offer significantly better opportunities than most. Underserved markets have growth potential and less competition. Position yourself in an underserved market and your business model will be much stronger. Markets are underserved because

- The market is growing and too few vendors serve the market. Most new businesses chase this classic market. Markets like Android application development, social media platforms, 3D printing, and passenger space travel are examples.

- The market is stagnant or shrinking and vendors flee. An overcorrection by competition can create opportunities.

- The market is considered unattractive. Some possible reasons:

- Perceived profitability: Rent-A-Center profits in a market others consider too dicey.

- Perceived size: Walmart found a market serving towns under 20,000 in population while competitors focused on large cities.

- Being unsexy: Markets like portable toilets, paper manufacturing, and salt mining have far less sex appeal than iPhone application development and can offer opportunities because of this lack of appeal.

Looking for Niche Attractiveness

After you pick an attractive industry for your business model (see the preceding section), it’s time to find an attractive niche. Your niche market is a subset of the overall market you participate in.

Know the power of a good niche

Picking the right niche may be more important than picking the right industry. For example, Vistaprint was founded in 1995 when the traditional printing business was getting crushed. Thousands of printers went out of business during the 1990s and early 2000s. During that time, Vistaprint grew into a billion-dollar business. How could Vistaprint grow when other printers were dramatically shrinking? Vistaprint targeted micro and small businesses considered too small for traditional printers. Combined with ingenious leverage of technology, Vistaprint turned unprofitable small customers into one of the most profitable printing operations in the world.

Unlimited niches exist

Good news! You can find unlimited niches within any market. At the core of many successful companies’ strategies was the creation or refinement of a new niche. Here are some examples:

- Panera Bread: Healthier, higher-quality sandwiches aimed at the fast-food industry.

- Häagen-Dazs: High-end ice cream at triple the price versus other ice creams in the frozen dessert industry.

- Starbucks: Not just a cup of joe — an experience. You could argue that Starbucks is in the restaurant industry, and it is. However, Starbucks also competes against convenience stores for coffee sales. The niche in either case is the customer who wants the full Starbucks coffee experience.

- McDonald’s: Fast, consistent food. This niche in the restaurant business is mature and crowded today, but when McDonald’s started, it was a new and untapped market. By catering to customers who wanted consistency in fast food, McDonald’s dominated this niche.

- Coach: Everyday luxury. Coach bags are more stylish than a department store brand but priced much more reasonably than high-fashion brands. This half high-fashion, half department-store niche has worked well for Coach and other everyday luxury brands.

- iPad: An email and Internet toy. Apple found a great niche between a laptop, Gameboy, and smartphone.

How many different niches can the hamburger business support? A lot more than anyone expected. The hamburger was invented around 1890, and the first hamburger restaurants began appearing in the 1920s. Since then, dozens of spins on making a hamburger have appeared. Here’s a partial list of hamburger chains and their niches.

Chain |

Niche |

McDonald’s |

The kids’ burger chain |

Wendy’s |

The adults’ burger chain |

Red Robin |

Gourmet burgers |

White Castle |

Craveable sliders |

Rally’s |

Drive-through only |

Steak ’n Shake |

Sit-down burgers with a diner feel |

Five Guys |

Simple, fresher burgers and fries |

Markets have a habit of splitting

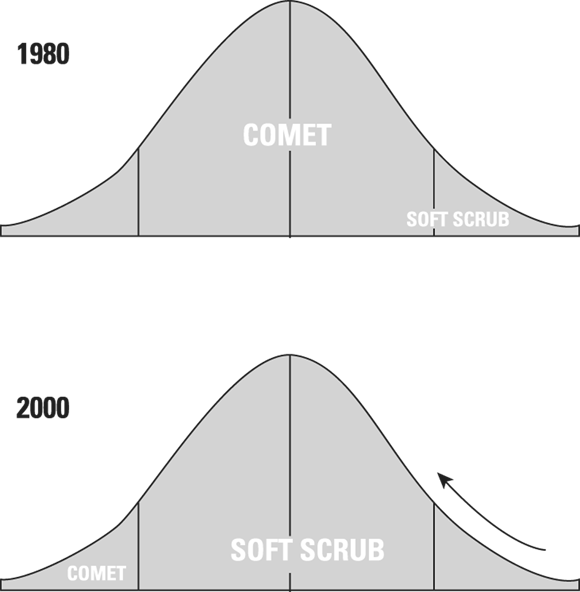

As markets mature, they tend to split into more and more niches. Niches that used to comprise a small portion of the market can become huge. Fifty years ago, abrasive cleaners such as Comet dominated the household cleaner market. In 1977, the Clorox Company introduced the niche cleaner Soft Scrub. The product had a limited market for those looking for an occasional alternative to hard abrasives. Over time, cream cleaners became the largest segment of the household cleaner market. Now you can find niche cream products such as Cerama Bryte stovetop cleaner for specialty uses.

If you think of the overall market as a bell curve in which the largest market exists in the fat portion of the bell curve, the best niches exist on the fringes of the market. Think of the left fringe as low-cost options and the right edge as high-cost options. Figure 4-1 shows bell curves for the household cleaner market.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-1: Bell curves for the household cleaner market.

At one time, dry cleaners like Comet held the bulk of the market. Soft Scrub entered the market as a liquid specialty cleaner on the right fringe of the market. Soft Scrub garnered customers who didn’t want the harsh abrasive in a dry cleaner. Over time, the appeal of liquid cleaners versus dry cleaners grew, and Soft Scrub replaced Comet as the main portion of the market (the fat part of the bell curve). Comet was relegated to the least attractive portion of the market (the left fringe), appealing to cost-sensitive customers willing to use old-fashioned cleaners.

Both edges of the bell curve offer a variety of niches. Walmart found a niche on the left fringe by providing buyers in small towns a low-cost department store. Today, Walmart represents the fat part of the bell curve, and dollar stores have carved out a niche on the left fringe.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-2: Entering the market on the fringes.

Find unserved or underserved markets

The best way to create a good niche is to find an unserved or underserved market. All blockbuster products do this. No one bought a cellphone for what it was; people bought it for what it did — made them feel safer and more productive while driving, for example. The underserved market for cellphones wasn’t one for better phones; it was for the capability to communicate in situations where it was previously impossible.

What does underserved mean? If the market was obviously underserved, an existing player in the market would fill the void. Some guesswork is involved in predicting what underserved means. You have to use your business judgment and then guess. Only the market knows what’s needed, and the only way to find out is to take it to the market.

Sometimes it’s easy to identify an underserved market. A fast-growing suburb needs gas stations, restaurants, and services in prime retail locations. Exponential growth in the use of smartphones creates users faster than the applications needed to serve them.

Instead of going for the obvious niche, be willing to take some chances and pick a less obvious niche. If everyone is chasing mobile phone growth by writing iPhone and Android apps, take a chance on Microsoft apps. For smaller companies, having a less competitive niche can be far more advantageous than being a very small fish in the big pond.

How can you find these elusive unserved or underserved markets?

- Personal experience: Many great products and companies have been created by an entrepreneur’s discontent with the status quo. Fred Smith wondered why letters couldn’t be delivered overnight when he conceived FedEx. While traveling in Italy, Starbucks’s Howard Schultz wondered why European-style cafes wouldn’t work in America.

- Friends and relatives: If you aren’t the cutting-edge type, look to friends who are. What products and services are they buying and why? What problems do they wish they could solve?

- Research trends: You don’t need to catch a trend to find a great niche; however, catching a trend can make your niche much better because the growth is built-in.

- Hired experts: Professional business plan writers, business model consultants, futurists, or other gurus can help you find a niche.

- Luck: Angie’s List was founded in 1995 when the Internet didn’t exist for very many people. Angie’s List was simply a monthly booklet sent to members with reviews of home contractors. Its popularity was concentrated in historic neighborhoods where repairs were frequent and expensive. Angie’s List was a nice little business that never envisioned the tidal wave that would carry it to become the leader in its niche. When the Internet turned the Angie’s List business model upside down, it also made it better. Instead of a localized printer of recommendation booklets, Angie’s List built a comprehensive website.

Checking Out Customer Attractiveness

You can create an attractive market niche (see the preceding section), but have it destroyed by bad customers. Attractive customers have a strong need for your offering, value the solution to their problem more than your product costs (that’s a strong value proposition), have disposable income to spend on your offering, pay their bills on time, and exist in sufficient numbers to make your venture profitable.

Most business models have customers that are neither exceptionally attractive nor exceptionally unattractive. Most business models don’t need to focus on customer attractiveness for long because the old mantra “all customers are good customers” is true most the time. However, you do have to study customer attractiveness.

The most prominent example of gaining the most attractive customer is the retail mantra “location, location, location.” What does an outstanding retail location get you? Outstanding customers, that’s what. A high-end retail mall has the same industry attractiveness and niche attractiveness regardless of where it’s located. Whether the mall is located in the hottest new suburb or the middle of farmland, the industry and niche attractiveness remain the same. However, the high-income customers available in the hot new suburb are typically viewed as more attractive than those in rural locations.

For example, Rent-A-Center is in the same industry as Best Buy. The two companies have some niche overlap, but they serve significantly different customers. Best Buy serves customers who can afford to purchase a television in full. These customers have either cash or pre-arranged financing like a credit card. Rent-A-Center caters to customers with lesser credit availability. Rent-A-Center extends credit to buyers deemed undesirable by traditional retailers like Best Buy. Rent-A-Center accepts monthly or weekly payments from customers until the item is paid in full. Due to the differences in the customer segments they serve, Rent-A-Center’s business model is significantly different from Best Buy’s:

- Best Buy serves a larger number of buyers who are more financially stable and makes money with a traditional retail business model — buying and selling merchandise.

- Rent-A-Center is closer to a specialty finance company that happens to sell appliances. Because Rent-A-Center doesn’t collect payment in full upfront, the company has many profit areas that Best Buy doesn’t have. Finance fees, high interest rates on loans, repossession fees, and more account for the bulk of Rent-A-Center’s profit.

Many businesses would consider the customers of Rent-A-Center less than desirable. However, Rent-A-Center has created a profitable business model selling to these supposedly less-than-desirable customers. Because the Rent-A-Center model accounts for sporadic and occasional nonpayment, it’s a workable business model.

Interestingly, you can have a customer niche within your customer niche. Your products are marketed to target a certain segment or niche. However, customers within any niche, no matter how tight, are widely varied. Coach bags fill a niche between the everyday bags you can find at JCPenney’s and the high-end bags you can find in Paris. Within this niche you can find Louis Vuitton customers slumming it a bit and middle-class folks looking for a bit of everyday luxury.

The question you need to answer is which of the sub-segments the marketing is directed to. In the case of Coach bags, the marketing is clearly directed at the middle-class buyer looking for everyday luxury.

Here’s another example: Starbucks attracts the most affluent and desired customers in the coffee industry. However, within Starbucks niche are buyers who stretch themselves financially to buy a $5 latte and buyers who spend hundreds of dollars every month at Starbucks. The niche Starbucks markets to is customers who want Starbucks as a lifestyle choice rather than just a cup of coffee.

Finding Your Place on the Industry Value Chain

You want to find the best place on the industry value chain. Every firm involved in getting a product from initial creation to purchase and consumption by the end consumer adds value in the form of activities, incurs costs, and has a resulting margin. Some positions in this value chain offer a greater opportunity than others.

Different industries value the places on this value chain differently. For instance, clothing retailers enjoy a more profitable position on their value chain than the clothing manufacturers. In automobiles, retailers tend to make less than the manufacturers. In some industries, no desirable places on the value chain are available, making the overall market less attractive for your business.

Consider a cup of coffee. Several operators add value to your daily cup of joe. However, the market rewards some activities much more richly than others. If your business model is to be the most successful, you want to assume a position on the value chain that offers the best potential profits. Table 4-1 shows the value chain for coffee.

TABLE 4-1 Value Chain for Coffee

Firm |

Value Added |

Key Activities |

Coffee bean grower |

Operations |

Farming |

Shipper |

Logistics |

Transportation and logistics |

Coffee roaster |

Operations |

Converting beans into drinkable coffee |

Marketers (Folgers, Starbucks) |

Sales |

Branding, sales, customer service |

Retailer |

Sales |

Merchandising |

Coffee prices go up and down, but the principles involved don’t change. Suppose that whole green Columbian coffee beans sell for $1.97 a pound. Assume the farmer has costs equal to about half that. The farmer’s margin is 98.5 cents per pound of coffee. The roaster buys the coffee from the farmer for $1.97 a pound and transports it, roasts it, and grinds it. The cost of logistics and transportation is around 2 cents per pound. The roaster then sells it to a coffee service, consumer products company, or retail outlet. Unbranded wholesale coffee sells for around $5 per pound. If the coffee roaster’s cost of operations is about half the $3.03 per pound value added, then the coffee roaster makes a margin of around $1.51. If the coffee is branded (Starbucks, Folgers, Seattle’s Best), add a dollar or two to the value added. Note that almost all the value added by branding drops to profit/margin. Finally, a company like Starbucks, Folgers, Kroger, or a coffee service delivers the coffee to the consumer. Folgers coffee sells for $9.99 a pound (Starbucks, $13.95 per pound). Therefore, the retail seller of Folgers has added about $4 of value (mostly margin). This comprises the entire value chain for a one-pound bag of coffee.

Table 4-2 shows the value added by each function and the approximate margin. Note that the marketing and sales related functions are much more handsomely rewarded than the functions that make the product.

TABLE 4-2 Value Added for Coffee

Firm |

Cost Added per Pound |

Margin Earned per Pound |

Total Value Added |

Coffee bean grower |

$0.985 |

$0.985 |

$1.97 |

Shipper |

$0.015 |

$0.005 |

$.02 |

Coffee roaster |

$1.52 |

$1.51 |

$3.03 |

Marketers (Folgers, Starbucks) |

$0 |

$2 |

$2 |

Retailer |

$2 |

$2 |

$4 |

Savvy entrepreneurs have also created new positions on the value chain to carve value away from existing players. For example, in the field of law, several new players have emerged to carve out a portion of the value chain traditionally owned by lawyers. Law firms in India specialize in large-scale complex research only. Some firms audit bills from law firms in an attempt to save their clients money. Both of these industries used to be part of the law firm value chain.

Ironically, there seems to be very little correlation between the amount of work or the difficulty of work and the amount of value added in the value chain. As you can see from the coffee example, the hardest work is done by the farmer. The farmer takes the risk of bad weather, has the highest number of employees, and puts in the most hours proportionately. However, the farmer makes the least amount of money on the value chain.

By combining industry attractiveness, niche attractiveness, and customer attractiveness, you can understand the overall market potential. This chapter refers to this combination as the market attractiveness from this point forward. Market attractiveness is one of the most important aspects of your business. It’s difficult to imagine a strong business that sells to lousy customers in a bad industry and small niche market.

By combining industry attractiveness, niche attractiveness, and customer attractiveness, you can understand the overall market potential. This chapter refers to this combination as the market attractiveness from this point forward. Market attractiveness is one of the most important aspects of your business. It’s difficult to imagine a strong business that sells to lousy customers in a bad industry and small niche market. As you choose your industry, keep in mind that the business landscape is always changing. Gas stations used to fix cars; now they sell donuts and sandwiches. If you look into the future, it can help you determine whether your chosen industry has peripheral growth opportunities or potential threats.

As you choose your industry, keep in mind that the business landscape is always changing. Gas stations used to fix cars; now they sell donuts and sandwiches. If you look into the future, it can help you determine whether your chosen industry has peripheral growth opportunities or potential threats.