Chapter One

MANYA (Hydrogen)

THE WOMAN KNOWN to the world as Madame Curie entered the world on November 7, 1867, as Marya Salomea Sklodowska. The youngest of five children, she answered to Manya at home, as well as to the diminutive Manyusya, and sometimes Anciupecio. She had more pet names than any of her siblings because, in addition to being the baby of the family, she was also petite and precocious. She learned to read on her own by age four, and with such absorption that the older ones made a sport of scheming to distract her.

She owed her early interest in science to her father, Wladislaw Sklodowski, who taught mathematics and physics at a Warsaw high school for boys. He kept a barometer and other scientific apparatus in the family apartments, and communicated his enthusiasm for such things to his son and four daughters. He likewise revered language and literature. When he read aloud on Saturday evenings, he often chose a book in English, such as Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield, translating the text into Polish on the fly. Selections in French or German required no such interpretation on his part for the sake of the children, who spoke several foreign tongues. He also inculcated in them a special reverence for the poets who celebrated the feats of Polish heroes.

The father’s only fault, according to family lore, was his devotion to the lost cause of Polish nationhood. The country, once the largest in Europe, had been gradually overpowered by its aggressive neighbors, Austria, Prussia, and Russia, so that by 1795, all the land area long known as Poland had been partitioned and absorbed by the surrounding nation-states. Citizens who continued to consider themselves culturally Polish united to regain sovereignty, but the nationalist uprisings of 1830 and 1863 were brutally quashed, their leaders hanged, and thousands of followers exiled to Siberia. As a proud Pole teaching at a gymnasium in Russian-ruled Warsaw, Sklodowski provoked the anger of his superior, who fired him. Around that same time, unfortunately, the patriotic professor invested his life savings in his brother-in-law’s business venture—a steam-powered mill in the countryside—which failed and ruined them both.

A deeper misfortune befell Manya’s mother, Bronislawa Boguska Sklodowska, who had also taught school in Warsaw and served as headmistress of a private academy for girls. A few years after the birth of her fifth child, she developed the first signs of tuberculosis—a disease as deadly as it was common in those days. Though the routes of contagion were not well understood, she took every precaution she could think of, such as keeping separate dishes for herself. Fear of infecting her children forced her to stop hugging and kissing them. As the disease worsened, she sought rest and fresh air (the only available orthodox treatments) at mountain spas in Austria and southern France, accompanied by her eldest daughter, Zofia. For two years, beginning in 1874, Manya lamented the extended absences of these two beloved figures.

Meanwhile the cost of the mother’s care drove the family into ever poorer lodgings. The desperate father took in more and more student boarders. These boys slept in the children’s bedrooms, pushing Manya and her sisters into the living room, where still more boys came to study in the daytime. Under these overcrowded conditions, the two older Sklodowska girls, Zofia and Bronya, contracted typhus. Bronya recovered after several feverish weeks, but fourteen-year-old Zofia, who had for so long acted as nursemaid to her mother, died of the illness in January 1876. Their mother’s death followed two years later, in May 1878, when Manya was ten.

“This catastrophe was the first great sorrow of my life and threw me into a profound depression,” Mme. Curie disclosed decades later in an autobiographical essay. “My mother had an exceptional personality. With all her intellectuality she had a big heart and a very high sense of duty … Her influence over me was extraordinary, for in me the natural love of the little girl for her mother was united with a passionate admiration.”

The remaining family members drew even closer together. Bronya assumed many responsibilities of managing the household. The bereaved husband preserved family traditions, including reunions with relatives and friends, which “brought some joy” to all of them.

Manya had started school at the girls’ academy on Freta Street—the same one her mother had attended, later taught at, and ultimately supervised. Manya had in fact been born in the Freta Street School, near the center of Warsaw, in the apartment that came as a privilege of her mother’s position. The family vacated that home in 1868, while she was still an infant. When she was old enough to return as a first-grade student, she and her sister Helena, one year older, walked some distance to reach the place from their Novolipki Street residence, which lay west of the city center, on the border of the Jewish quarter.

At the beginning of third grade, in the fall of 1877, the two sisters reported to a different school, closer to home. Because it was a private school for girls, its bold administrator provided a real Polish education in quiet defiance of the Russian authorities. Often the arrival of an official inspector would send the students and teachers scrambling to hide their Polish texts and feign engagement in one of the accepted subjects, such as sewing or Russian history—in Russian. More than once Manya, with her excellent command of the Russian language, was singled out to answer an inspector’s questions. “This was a great trial to me, because of my timidity,” she later wrote. “I wanted to run away and hide.”

The next school year, which began within months of her mother’s death, found her at Gymnasium Number Three, a government-run girls’ school where, as the grown Manya recalled, the teachers “treated their pupils as enemies.” Only from such a government-sanctioned school, however, could she obtain a legal diploma. Now she walked to school with her friend Kazia Przyborowska, whom she loved like another sister, and after school she returned home with Kazia, whose mother coddled Manya and plied her with sweets.

“Do you know, Kazia,” Manya wrote from a summer vacation at an uncle’s farm, “in spite of everything, I like school. Perhaps you will make fun of me, but nevertheless I must tell you that I like it, and even that I love it. I can realize that now. Don’t go imagining that I miss it! Oh no; not at all. But the idea that I am going back soon does not depress me, and the two years I have left to spend there don’t seem as dreadful, as painful and long as they once did.”

She was fifteen when she finished school on June 12, 1883, first in her class and winner of the gold medal—a distinction achieved earlier by her brother, Józef, and sister Bronya. Józef had gone directly from the boys’ gymnasium to medical school at Warsaw University. Bronya would have loved to follow that same path, but it was open to men only, so she dreamed of someday studying medicine in Paris, where women were accepted at the Sorbonne. Helena possessed enough education as a gymnasium graduate to become a teacher like their mother, and enough musical talent to sing professionally if she chose to. Before Manya could form a clear picture of her own future, her father rewarded her scholastic success by sending her on a year’s vacation with extended family, beginning with her mother’s brothers in the southern countryside—the same relations who had embroiled him in the financial debacle. Now they treated Manya to the time of her life.

“I can’t believe geometry or algebra ever existed,” she wrote to Kazia. “I have completely forgotten them.” The leisure activities she listed in her letters included reading “harmless and absurd little novels,” walking in the woods, rolling hoops, playing childish games such as cross-tag and Goose, swinging “hard and high,” swimming, fishing with torches for shrimp, horseback riding, and eating wild strawberries. She had the family dog, Lancet, with her in the country that summer, and reported his noisy misbehavior as part of her enjoyment. When the season turned, she went farther south to visit her father’s brother in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, where she spent the next few months.

On festive winter nights Manya and her cousins, dressed as peasant girls, sped off through the forest in a sleigh, guided by young men on horseback. Other sleighs full of revelers met them at the first house they encountered, and a sleigh full of musicians, too. They danced the mazurka and the oberek, also the waltz, for hours. Then, instead of returning home, they rode on to the next house, and the next, in a custom called the kulig. Everywhere they stopped they found a feast prepared for them. Daybreak arrived before they finished their partying at all the hosts’ homes.

Her year of freedom from care extended through the summer of 1884, when she and Helena were invited to the rural estate of one of their mother’s former pupils. Up north in Kempa, the riverine scenery and hospitality topped even the amusements of the kulig. As she told Kazia, “Kempa is at the junction of the Narev and Biebrza rivers—which is to say that there is plenty of water for swimming and boating, which delights me. I am learning to row—I am getting on quite well—and the bathing is ideal. We do everything that comes into our heads, we sleep sometimes at night and sometimes by day, we dance, and we run to such follies that sometimes we deserve to be locked up in an asylum for the insane.” On August 25, the morning after the St. Louis night ball, by Manya’s own account, she discarded her new dance shoes because she had worn out their soles.

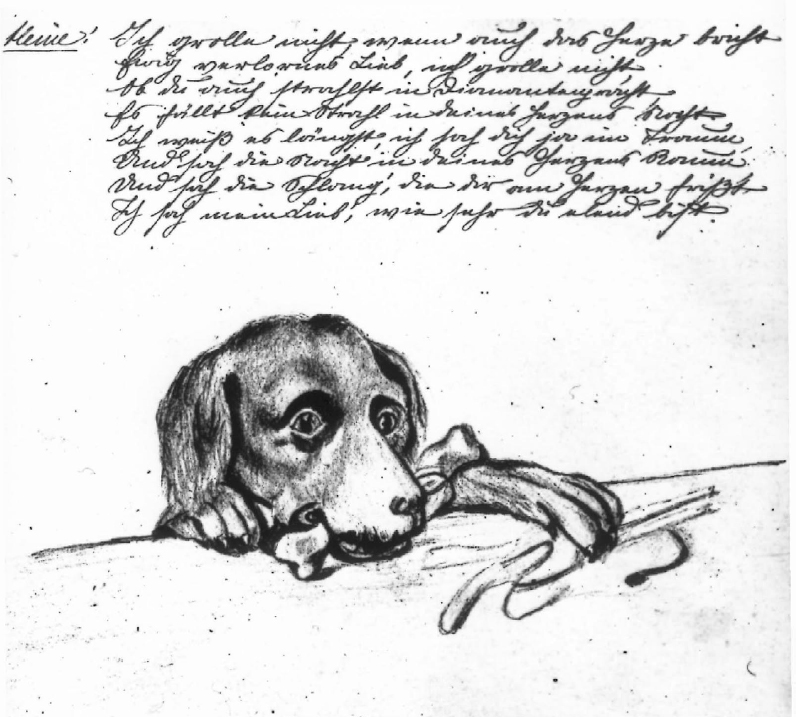

Manya’s portrait of Lancet in her diary

Musée Curie (coll. ACJC)

She returned to Warsaw, to her father’s much smaller quarters. He still taught classes, but no longer took in boarders. Manya, nearing her seventeenth birthday, could now add her own wages to the family’s support by giving private lessons in French, arithmetic, or geometry. It was not an easy way to make a living. “A person who knew of us through friends came to inquire about lessons,” she noted. “Bronya told her half a ruble an hour, and the visitor ran away as though the house had caught fire.”

To further their own education, she and Bronya attended secret sessions of the “Flying University.” The limited course offerings of this itinerant institution depended on the expertise of its volunteer professors, who met with eight or ten students at a time in one or another private residence. Classroom locales shifted often to avoid detection by the police. While study topics such as anatomy and natural history could hardly be considered subversive, providing higher education to women was itself illicit under Russian rule.

In the spirit of the Flying University, Manya made regular visits to a dressmaking shop where she read aloud to the employees and built up a lending library for them of books in Polish. On her own she read fiction and philosophy, sketched flowers and animals (including Lancet) in a notebook, wrote verses, and figured out a plan that would enable her—and Bronya—to study in France.

She would get a job as a governess. Not only would she earn more money living with a family, but also her room and board would be covered, freeing the bulk of her wages—maybe as much as 400 rubles a year—to pay Bronya’s way in Paris. In another five years, when Bronya became a doctor, then it would be Manya’s turn to go to the Sorbonne, and Bronya’s duty to support her.

Bronya, who was twenty, had saved just enough money to get to Paris and see herself through one year at the Faculty of Medicine. The plan fell into place in the autumn of 1885, just as Manya had envisioned, but by December her part of it had already fallen apart. Her placement with the B—s, a family of lawyers, made her feel like a prisoner. As she confided to her cousin Henrietta, “I shouldn’t like my worst enemy to live in such a hell. In the end, my relations with Mme. B— had become so icy that I could not endure it any longer and told her so. Since she was exactly as enthusiastic about me as I was about her, we understood each other marvelously well.” Her presence in the B—s’ home ended her innocence regarding human nature. “I learned that the characters described in novels really do exist, and that one must not enter into contact with people who have been demoralized by wealth.”

She immediately found a new position. This one pulled her far away from home—to Szczuki, some fifty miles north of Warsaw—but placed her with a more tolerable family and paid an annual salary of 500 rubles. En route on January 1, 1886, she imagined she was headed to forested hills of the kind she had admired the previous summer. Instead she found herself surrounded by two hundred acres of agricultural fields, all devoted to growing beet root for sugar production. Indeed, the business of turning the harvested crops into sweetener took place in a dreary-looking factory adjacent to the home of the Zorawski family, her new employers. Past the factory a cluster of huts housed the peasants who worked on the land. The nearby river offered scant recreation, but served the factory and also received its waste. Still, after one month in residence, Manya let Henrietta know how much her situation had improved: “The Z.’s are excellent people. I have made friends with their eldest daughter, Bronka, which contributes to the pleasantness of my life. As for my pupil, Andzia, who will soon be ten, she is an obedient child, but very disorderly and spoiled. Still, one can’t require perfection.”

She worked seven hours a day—three with Bronka and four with Andzia. The antics of the younger children, a boy of three and a six-month-old baby girl, further brightened her spirits. She had yet to encounter the three older sons, who were away at boarding school and university in Warsaw.

Manya and Bronya Sklodowska, 1886

Musée Curie (coll. ACJC)

Sometimes Mme. Zorawska begged Manya to help entertain guests by conversing with them or sitting in as a fourth at card games, and of course she complied. In her free time, of her own volition, she organized a class for the peasant children, teaching them for two hours a day to read and write in Polish, since they learned only Russian at school. Late at night and early in the morning, she pursued her own reading toward her ultimate goal of studying physics and mathematics at the Sorbonne. She named some of these books in a December letter to Henrietta: John Frederic Daniell’s Physics, Herbert Spencer’s Sociology in French, and Paul Bert’s Lessons on Anatomy and Physiology in Russian. She was reading them all at the same time, she told Henrietta, because “the consecutive study of a single subject would wear out my poor little head which is already much overworked. When I feel myself quite unable to read with profit, I work problems of algebra or trigonometry, which allow no lapses of attention and get me back into the right road.”

She let one disruption in her busy schedule go unmentioned in her letters to Henrietta: Sometime during her first year at Szczuki, she met and fell in love with the Zorawskis’ oldest son, Kazimierz, the university student. Their romance led to a serious commitment, but when Kazimierz announced that he and Manya were engaged, his parents forbade him to marry the penniless governess. Kazimierz could not flout their wishes, and Manya, who could not afford to lose her income, swallowed her rage and shame and stuck to her work.

The episode darkened her view of the future. In March 1887, three months into her second year at Szczuki, when her brother was contemplating a medical office in the provinces, she begged him to hold out for something better in the big city. If he compromised, she said, then she would “suffer enormously, for now that I have lost the hope of ever becoming anybody, all my ambition has been transferred to Bronya and you. You two, at least, must direct your lives according to your gifts. These gifts which, without any doubt, do exist in our family must not disappear; they must come out through one of us. The more regret I have for myself the more hope I have for you.”

By the following March she was even more despondent. “If only I didn’t have to think of Bronya,” she confessed to Józef, “I should present my resignation to the Z.’s this very instant and look for another post …” Despite the hopelessness and frustration she sometimes vented, she continued her own higher studies. “Think of it,” she wrote Józef, “I am learning chemistry from a book. You can imagine how little I get out of that, but what can I do, as I have no place to make experiments or do practical work?”

At Easter in 1889, having fully discharged her duty to Andzia, she left Szczuki for another governess position, this time with the wealthy Fuchs family in Warsaw. She found living in their luxurious home pleasant enough, but was happy to leave it after one year to move in with her father once again and rely on giving private lessons for her income. When she re-enrolled at the Flying University, she found its student body had swelled from two hundred to one thousand women, and its classrooms had perforce relocated from scattered homes to various discreet institutions.

Through an older cousin on the Boguski side, she gained access for the first time to a real laboratory, located in central Warsaw at the Museum of Industry and Agriculture. In the evenings and on Sundays, by herself, she would go there to try out some of the experiments described in the treatises she was reading on chemistry and physics.

“I learned to my cost that progress in such matters is neither rapid nor easy,” she later reflected. Even so, “I developed my taste for experimental research during these first trials.”

MANYA’S ACCOMMODATING COUSIN, Józef Boguski, had studied chemistry in his youth at the University of St. Petersburg with Dmitri Mendeleev, creator of the periodic table of the elements. This remarkable chart summarized everything known about the building blocks of the material world. At a glance it showed which elements shared common properties, which ones were most likely to combine with which others, and in what proportions. Moreover, it gave scientific meaning to the age-old terms “atom” and “element.”

“Atom” (a-tom) meant “un-cuttable” to ancient Greek philosophers pondering the smallest possible divisions of matter. By the nineteenth century “atom” indicated an invisible, indivisible particle, inconceivably tiny yet still retaining a given element’s traits. “Element,” through the long course of its history, had described a variety of essential entities, such as fire, air, earth, and water. Artisans in diverse early cultures smelted iron, alloyed copper with tin to make bronze, exploited the ornamental virtues of silver, and appreciated the utility of sulfur for cleaning, bleaching, and making medicines and matches. In the Middle Ages, alchemists endeavored to convert certain elements from a base form, such as lead, to the purity of gold. A list of thirty-three “simple substances” drawn up on the brink of the French Revolution added the gases hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen to the chemist’s supply. Nineteenth-century discoveries of calcium, potassium, silicon, iodine, and a couple dozen others had increased the number of known elements to sixty-three by the time Mendeleev tried to impose some kind of order on the ever-growing assortment.

He chose atomic weight as his organizing principle. Although no scale could weigh an entity as minuscule as an atom, the preceding century of theory and experimentation had shown chemists a way around that problem: By weighing equal volumes of different gases, they found hydrogen to be the lightest of all, and assigned it an atomic weight of one. In the reaction between hydrogen and oxygen to yield water, the quantity of oxygen always outweighed that of hydrogen by a factor of eight, so the atomic weight of oxygen was set at eight—until chemists realized that water contained two atoms of hydrogen for every one of oxygen, and corrected oxygen’s atomic weight to sixteen. Since both hydrogen and oxygen combined readily with many another element, these two helped establish the atomic weights of iron, sodium, magnesium, aluminum, and more.

Mendeleev’s first published periodic table (in Russian)

Ann Ronan Picture Library / Heritage Images / Science Photo Library

Atomic weight proved to be an element’s most enduring feature. It alone held fast while characteristic colors, textures, and odors typically disappeared when elements combined in chemical reactions. Sodium and chlorine, for example—one a soft, silvery-white metal, the other a poisonous gas—united to form crystals of ordinary table salt (sodium chloride), but their atomic weights remained unchanged.

When Mendeleev arrayed the known elements in order of ascending atomic weight, he was stunned to see certain chemical properties repeat at regular intervals. This periodic repetition of similarities convinced him he had perceived a law of nature.

Mendeleev published his periodic table in 1869 in a limited edition of two hundred copies, as well as in journal articles and in a textbook he wrote for his students at St. Petersburg. Since its debut, and thanks to Mendeleev’s own frequent improvements over the following twenty years, his periodic table had become a laboratory fixture. The most current revised version available to Manya Sklodowska at the Museum of Industry and Agriculture included three elements only recently identified: gallium, scandium, and germanium, each named for its discoverer’s homeland. All three occupied places on the periodic table that Mendeleev had intentionally left blank, as though awaiting their arrival. A few unusually large weight differences between successive elements had tipped him off to the possibility of latecomers. In making accommodation for them, he had given them provisional names—such as “eka-aluminum” for gallium—and approximated their atomic weights. Those predictions had since proven prophetic.

As Manya could see, empty spaces still punctuated the periodic table. At any moment, another new element might emerge to fill a vacant spot below tellurium, below barium, between thorium and uranium, or perhaps beyond uranium—the element deemed to be the heaviest.

News from Bronya in Paris came as fulfillment of the sisters’ longstanding bargain. Bronya had married a fellow student, a Polish expatriate named Kazimierz Dluski, in the summer of 1890, and established a small medical practice with him. There was room in their apartment for Manya.

“Your invitation to Paris … has given her a fever,” Wladislaw Sklodowski wrote to his elder daughter. “I feel the power with which she wills to approach that source of science, towards which she aspires so much.”

On Bronya’s advice, Manya shipped her mattress and other bulky belongings by freight, to save herself the trouble and expense of buying new ones in France. As a further economy, she chose the cheapest possible train fare—a mix of third- and fourth-class tickets that required her to bring her own folding seat for the section of the journey crossing Germany, plus enough food and drink to see her through three days’ travel.

“So it was in November, 1891, at the age of twenty-four,” she recalled three decades later, “that I was able to realize the dream that had been ever present in my mind for several years.”