Chapter Twenty-Two

FRÉDÉRIC (Radon)

SINCE THE RUPTURE of the “Langevin affair” of 1911, Marie and Paul had strengthened the ties of friendship, common interests, and shared ideals that drew them together in the first place. They saw each other often, whether casually through social connections or formally via the Solvay Council, the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, and assorted Parisian scientific meetings. In November 1924, when Paul recommended one of his former students for a position at Marie’s lab, she agreed to see the young man immediately, even though he lacked experience in radioactivity.

Frédéric Joliot had studied physics with Langevin at Pierre’s old school, the École Municipale de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles, then worked briefly as an engineer at a steel plant in Luxembourg. Now twenty-four and nearing the end of his military service, he showed up in uniform for his anxious initial interview with the director. Since she asked only one question—When could he start work?—he told her nothing of his childhood exploits as an avid experimenter, or that, as a boy of six, he had clipped a photograph of Pierre and Marie Curie from a popular magazine, and still kept it hanging, framed, in his bedroom.

Joliot returned to the Radium Institute in mid-December, in civilian clothes. Madame assigned him to assist René Cailliet, a préparateur on the verge of retirement. She also counseled him to pursue his higher education while acquiring new lab skills. She held up her daughter as an example: Irène was only three years older than he, and already at work on her doctoral dissertation.

Irène’s thesis project concerned polonium, the first of her parents’ two element discoveries. Specifically, she sought to study its alpha radiation—the positively charged particles that polonium emitted as it decayed. Aware that scientists in several countries were similarly engaged, Irène did not let concern for their potential competition deter her. She planned to clock the initial speed of the alphas and the distances they covered—in centimeters—under various conditions. She would also track their ability to ionize the gases in their path as a function of distance traveled.

In January 1925, only a month into Frédéric Joliot’s tenure, bad news reached the Curie lab about two of its former students. Marcel Demelander and Maurice Demenitroux, working together at a small factory near Paris that produced thorium and mesothorium for medical use, had died within days of each other: first Demelander, age thirty-five, of a rapid-onset anemia, then Demenitroux, forty-one, of leukemia. Mme. Curie learned from their colleagues that both had been confined to cramped, poorly ventilated spaces, and denied the proven safeguards of lead screens, periodic blood tests, and frequent breaks for fresh air.

In response to these fatalities, the French Academy of Medicine appointed its newest member, Marie Curie, to a study commission that included Drs. Antoine Béclère and Claudius Regaud.

Their review of industrial working conditions revealed a widespread and alarming disregard for the safety practices observed at research laboratories. Those established precautions, the commissioners insisted in their report, must be widely adopted—and adapted to the specific situations and techniques in use in each venue. Any facility that handled or even transported “radioactive bodies,” they recommended, should be classified as “insalubrious,” and therefore subject to regulation by the Ministry of Work and Health.

Beyond her official participation in the matter, Marie took up a collection to aid the widows Demelander and Demenitroux.

Surely, she believed, the stated guidelines would suffice as protection. After all, no one at the Institut du Radium suffered any impairment. She herself had doubtless logged more lifetime exposure to radium than anyone in the world, yet here she was, a woman of slight build and nearly sixty years, still coming to the lab every day, still actively engaged in productive research. She did wonder sometimes, in her letters to Bronya, whether this or that bodily complaint could be blamed on radium, but only her hands showed signs of damage, and those burns had occurred long ago. Although she had likely inhaled more than her fair share of radioactive gas, her intake had obviously not amounted to a debilitating dose, let alone a lethal one.

Radium emanation had at last gained an official name, “radon,” approved by the recently established International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. “Radon” neatly abbreviated the “radioneon” suggested by Mme. Curie, and also achieved a pleasant harmony with the other noble gas names—argon, krypton, neon, and xenon. Many radioactivists referred to thorium emanation as “thoron,” and actinium emanation as “actinon,” though both of these were understood to be isotopes of radon, element number 86 on the periodic table. Harriet Brooks, who once hesitated to call the “new gas from radium” an element, and then spent years investigating the three emanations at laboratories in three different countries, had a third child now, Paul Brooks Pitcher, and a reputation in Montreal as an excellent gardener.

IF MARIE HAD been ignorant of risk and heedless of danger in her youth, she had nevertheless lived to tell about it, and was now doing everything in her power to assure the proper handling of radioelements in research and industry. She judged the Curie lab environment safe enough to serve as her own daughter’s workplace. In fact, from a coldly analytical standpoint, her two children constituted a natural experiment in radioactivity exposure. Irène had been a fixture in the Radium Institute for five years now, while Ève rarely entered the building. Between them, Irène boasted the more robust constitution.

Ève had just completed her formal education at the Collège Sévigné—the same school Irène attended after the co-op experiment ended—and was pursuing private music studies with pianist Alfred Cortot. The sisters remained as close as could be expected, given the differences in their ages and tastes. They even shared a few childhood friends among the regulars at l’Arcouest.

Ève always maintained that Marie treated her daughters equally, showing no favoritism. Her mother’s only fault, according to Ève, was to indulge the artistic teenager’s whims, letting her choose her own music teachers and methods of work, and enthusiastically encouraging her in one “capricious” plan after another. “She was bestowing too much freedom upon a being undermined by doubt,” Ève judged in retrospect, “who would have done better to obey firm indications.” At the same time, Ève understood her mother’s mindset—“she who had been led to her destiny” by “infallible instinct” and against “immense obstacles.” Ève saw the same drive, the same sort of innate resolve, in her older sister, their mother’s clone. With a mix of humor and bravado, Ève made light of her exclusion from the scientific discussions that dominated household conversation. As a little girl, she said, when she heard the two of them exchange algebraic expressions such as “Bb squared” and “BB prime,” she had pictured bébés like herself, but oddly shaped to fit in corners, or given special privileges.

On March 27, 1925, Irène upheld the family tradition by successfully defending her doctoral research at the Sorbonne. Because of her family history, the three professors who examined her could not help but be family friends of long standing, whom she had trusted as father figures all her life. André Debierne, Jean Perrin, and Georges Urbain deemed Mlle. Curie’s polonium work deserving, and the university awarded her the docteur ès sciences degree.

Frédéric Joliot, the recent hire, attended Irène’s thesis defense and congratulated her on the spot. Later that day, in the garden of the Institut du Radium, Paul Langevin joined the traditional celebration that Madame held to honor a new docteur at the Curie lab. Everyone drank tea out of beakers, with pipettes for stirrers, and ate cakes and cookies served in basins borrowed from the photography darkroom.

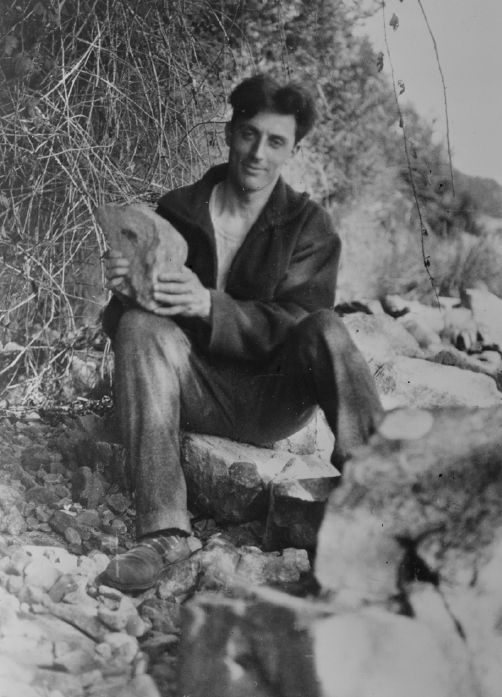

Now Irène had more time to coach Joliot, whose further formation as a radioactivist had fallen to her. He obeyed her every instruction. He also did as Madame had advised him, and in July he passed his second baccalauréat with distinction. By then he had befriended the other researchers, students, and staff, a few of whom were amused by the almost comical mismatch between tall, taciturn Irène and her handsome, gregarious acolyte.

Frédéric Joliot

Musée Curie (coll. ACJC)

As Frédéric himself later said of Irène, “With her cold exterior, forgetting sometimes to say good morning, she did not arouse a feeling of sympathy in the lab. But I discovered in this young woman, whom the others saw somewhat as a block of ice, an extraordinarily sensitive and poetic person who in many ways was the embodiment of what her father had been. I had read much about Pierre Curie, I had heard from teachers who knew him, and I found in his daughter the same simplicity, good sense, and humility.”

ONE DAY Catherine Chamié arrived from her morning of teaching at the Lycée russe and asked Mme. Curie to help her with an experiment. The lengthy process stretched through the afternoon and evening hours to well past midnight. On such occasions, when Madame did not leave the lab with her daughter as usual at the end of the day, Frédéric walked Irène home. And when the director left Paris in June for several weeks of travel, Frédéric became Irène’s more constant companion on long rambles through the forest of Fontainebleau.

“I find myself altogether too far away from you,” Marie wrote home to her daughters on June 3, 1925, from Warsaw, where she had gone to mark the start of construction on a new radioactivity research and treatment center. The city’s first radium institute, established in 1913, had perished with its on-site director, Jean Kazimierz Danysz, in the early months of the Great War. In recent years Bronya had raised funds to rebuild it by sending out thousands of postcards exhorting the populace to “buy a brick for the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Institute!” The same cards carried a quote from Marie, saying, “My most ardent desire is the creation of an institute of radium in Warsaw.”

At a sunny morning ceremony, the president of the republic, Stanislaw Wojciechowski, laid the first stone, Marie the second one, and the mayor of Warsaw, Wladislav Jablonski, the third. Other fetes followed for her at universities and learned academies. One orator hailed her as “the first lady-in-waiting of our gracious sovereign, the Polish Republic.” To some people, she was the very personification of radium.

After Poland, Prague. “I am astounded by the life I’m leading,” she wrote Irène on June 14, “and incapable of saying anything intelligent at this moment.” The next day would take her to Jáchymov (formerly Joachimsthal), to the mouth of the uranium mine that had yielded her original store of pitchblende. The life she was leading on this trip retraced the course of her old life, returning her as a conquering heroine to places where she had once been compelled to study in secret or to beg for mine tailings discarded as waste. Yet she felt depleted by all the fuss being made on her behalf. “I ask myself, what fundamental flaw of human nature makes people believe this form of agitation is necessary?” At the same time, she did not doubt the sincerity of her hosts in their determination to do every thoughtful thing for her. “I am here in a magnificent apartment, bedroom, salon and bath, with a view of the river and the hills beyond, surrounded by flowers given to me at the station, mostly roses because this is their season.”

MARIE RETURNED FROM the exertion and adulation of her tour to confront a new revelation about the marvel that was radium. A letter from Missy Meloney in America said that several young women whose job was to paint the numerals on luminous watch dials—with radium-laced pigment—had died of what appeared to be an occupational illness. Their employer, a private plant called the U.S. Radium Corporation, had opened in 1917 in Orange, New Jersey, to make glow-in-the-dark wristwatches for soldiers in the trenches, and now sold them to civilians. One currently afflicted dial painter, Margaret Carlough, was suing the company. Too disabled to remain at her job, she claimed that the recommended practice of pressing the fine tip of the dipped paintbrush between her lips to achieve a perfect point had destroyed her jaw.

“Lip-pointing” caused a dial painter to ingest a little of the paint, and with it a taste of radium, which was so like calcium in its chemistry that it readily settled into teeth and bones. Once lodged there, radium’s characteristic radiations—and those of its decay products—pervaded the body and destroyed the bodily tissues. When doctors tested Margaret Carlough’s breath during a diagnostic examination, they found that she exhaled radon along with the ordinary products of respiration.

More disturbing news reached Marie from a chemist she had met in America—Harlan Miner of the Welsbach Company in Gloucester, New Jersey, makers of mantles for gas lanterns. Miner was mourning “the quite sudden death from anemia of one of the young men in our organization,” and reported “the almost simultaneous death from the same disease” of another scientist at a nearby radium manufacturing company. Regular blood testing did take place at Welsbach, Miner’s letter said, but had apparently been instituted too late. “The man in our employ who died from anemia had a very low number of red corpuscles when we finally came to have him examined; and although he received blood transfusions it was not possible to save his life.”

Marie had never advocated the use of radium in commercial paint—or for any application outside a laboratory or hospital setting. The addition of thorium to the fabric of gas mantles had been common practice long before she recognized thorium’s radioactivity. And yet, responsibility for a host of ills seemed to be settling now on her shoulders.