Chapter Twenty-Six

ISABELLE and ANTONIA (Thallium)

“THE OLDER ONE GETS,” Marie observed in a reflective mood, “the more one realizes that knowing how to enjoy the present moment is a precious gift, comparable to a state of grace.” It was better to enjoy today today, she told her children, than to look back and savor it later, or to put off enjoyment till some distant tomorrow.

At sixty-two, having lived so much longer than either her mother or her husband, and with her future foreshortened accordingly, Marie spent her spare time preparing a revised second edition of her two-volume treatise on radioactivity and overseeing completion of the new radioelements factory at Arcueil, six miles from central Paris. The text encapsulated the history of the field she had named and still toiled in; the factory ensured its future.

Radioactivity itself was exquisitely time sensitive, with each radioelement defined by its rate of diminishment. Had she known, in the early days of her discoveries, the difference in longevity between polonium and radium, would she have saved her native country’s name for the more durable element?

The clocklike regularity of radioactive decay was what enabled scientists, despite their puny human lifespans, to extrapolate the sixteen-hundred-year half-life of radium and the multi-billion-year half-life of uranium. Even the lifetimes of individual atoms could be calculated: The average radium atom, though it had the potential to explode at any moment, endured twenty-five hundred years before expelling an alpha particle and turning to radon. In contrast, no single atom of polonium ever survived for more than a few months’ time.

The radium standard that Marie had fabricated in the summer of 1911—a petite glass tube containing twenty-two milligrams of her purest radium chloride—still served as the world’s arbiter of radioactivity. It resided, as per agreement, at the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures in Sèvres, but traveled to the Laboratoire Curie whenever required to test a secondary standard bound for some new member of the global radioactivity community. By 1930, half a dozen secondaries had been prepared in Vienna, tested in Paris, and exported with certificates signed by Marie Curie, Ernest Rutherford, and Stefan Meyer, officers of the International Commission for the Radium Standard.

Marie personally tested the first few secondaries, by comparing their degree of gamma radiation to that emitted by the international standard. Later she trained Renée Galabert to conduct the tests. Renée, who joined the lab in 1919, had advanced to head of the Measurement Service in 1921, the year Madeleine Molinier left to have a baby.

Thanks to the long half-life of radium, the international standard remained virtually unaltered after two decades of use. Each year saw it shrink by only one-thousandth of its initial mass. Still, time wrought important changes. The moment Marie sealed the glass tube, a predictable number of radium atoms transformed into radon, and the radon gas changed in its turn, yielding a series of solid daughter products. At the end of one month, a state of equilibrium prevailed inside the tube: the amount of new radon forming exactly balanced the amount dissipating.

The condition of radioactive equilibrium figured crucially in defining the “curie,” the unit of measure named in 1910 in honor of Pierre: one curie signified the quantity of radon (then called “radium emanation”) in equilibrium with one gram of radium. At the time, other radioactivists wanted to base the measure on a much smaller weight of radium—a milligram instead of a gram. Marie had insisted on a whole gram, however, and won her way. Perhaps she had been showing off, as she alone actually owned a full gram of radium. More likely she meant to set Pierre’s namesake unit on a generous foundation. As a result, measurements had been expressed ever since in millicuries.

In 1930 the international commission broadened the definition of the curie so that it was no longer tied exclusively to radon. From now on, one curie would equal the amount of any decay product in the uranium-radium family—polonium, say, or thallium—in equilibrium with a gram of radium.

Over time the comings and goings of personnel in the Curie lab had also achieved an equilibrium. The outflow of radioactivity-wise students, assistants, and independent researchers invited an influx of others equally eager to learn. In February 1930, Isabelle Archinard arrived from Geneva, on the advice of her thesis advisor, Charles Eugène Guye, who held the University of Geneva physics chair once offered to Pierre. Isabelle had also been pointed toward the Curie lab by Jean d’Espine, a veteran of five years’ collaboration in Paris with Marie, beginning in 1921. The Swiss d’Espine would have stayed longer at the Radium Institute, but he contracted tuberculosis and went home in 1926 to take the cure.

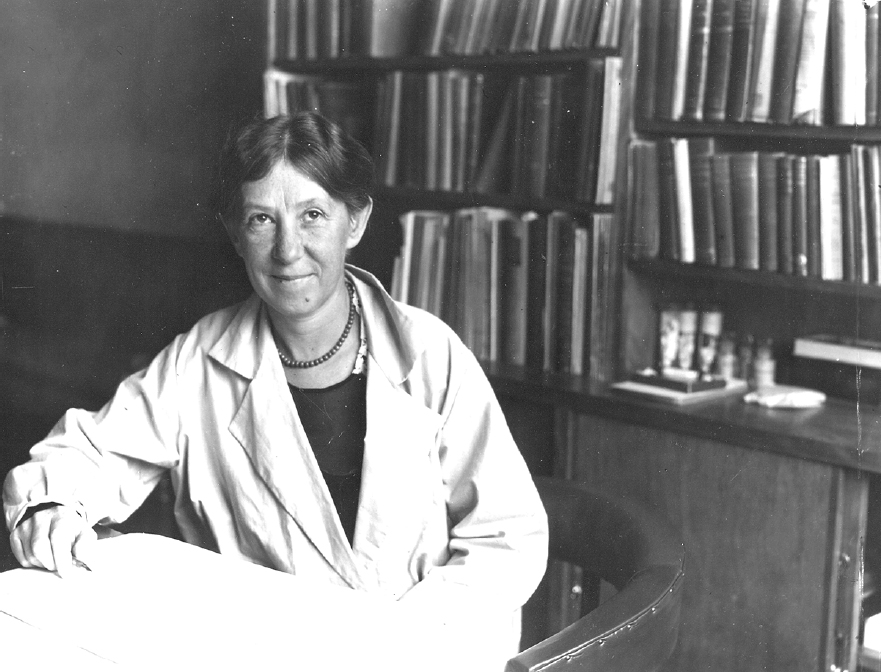

Prof. Ellen Gleditsch, 1935

National Library of Norway

Some lab alumnae—Ellen Gleditsch and Alicja Dorabialska in particular—returned periodically to undertake new studies in radioactivity or to spell Madame when she was teaching or lecturing abroad. Ellen, now Professor Gleditsch, had secured only half the space she requested in the long-awaited new chemistry building at the Royal Frederick University. Instead of ten rooms en suite, just two on the second floor and two in the basement were assigned to radiochemistry. No sooner had the chemists occupied the building than a plan emerged to move both the chemistry and physics departments to a shared new space at the university’s Blindern campus on the outskirts of Oslo. In the spring of 1930, Ellen again consented to serve on the planning committee.

“I have dangerously many interests beside my science,” she confessed to the student body at the 1930 jubilee. “I enjoy fiction, theater, and music, although not cinema. I am a member of the Female Students’ Choir and on its board. In recent years I have participated a little in international work, the peace movement, and intellectual cooperation.” Indeed, as part of her contract with the IFUW, Ellen had interacted with committees and subcommittees formed by the League of Nations. “I love sports and outdoor life, am a member of the Female Students’ Skiing Club, and know no better kind of summer holiday than a sojourn in the Norwegian mountains. I have lived long enough in France to appreciate that cooking is a great and important art, and I am known in many countries for my omelets.”

WHILE WRITING HIS doctoral dissertation on “The Electrochemical Study of Radioelements,” Frédéric Joliot earned extra money to support his growing family by teaching part-time at the École Pratique d’Électricité. On receipt of his graduate degree in mid-March 1930, he and Irène conceived new experiments together and also built and tinkered with the equipment needed to execute their ideas. Although the Radium Institute employed two full-time mechanics, an electrician, and a glassblower, Frédéric relished doing the mechanical work himself. He excelled at glassblowing, too. As he and Irène had predicted when they married, their contrasting natures and modes of thinking complemented each other well. Their hired nanny, Mme. Blondin, looked after Hélène during their long days at the lab.

Irène was still not well. In June she availed herself of the mountain air at Notre-Dame de Bellecombe, a ski resort near Mont Blanc in the Savoie region. A concerned Marie went with her. Organizing themselves around the daily rain showers, they walked for hours every afternoon. They ate, slept, took hot baths, and largely ignored the writing and editing work they had brought along. Ève sent Marie a book to read for relaxation. It was Colette’s latest, called Sido, a memoir about her mother. Ève deemed it “a masterpiece, every sentence of which is to be savored,” and Marie could only agree. Meanwhile Frédéric commuted regularly between Paris and Brunoy to spend time with Hélène. “The visits from her father,” Marie wrote Ève, “must comfort the dear child while her mother is so far away.”

Irène had built up a “depth of fatigue” that would not ebb easily, Marie feared, due to the persistent anemia. Nevertheless, the current regimen seemed to be doing her some good.

A plea from Paris abruptly ended Marie’s part of the mountain respite. Her colleagues Georges Urbain, Jean Perrin, and Émile Borel begged her to join them in a July 8 meeting with Gaston Doumergue, the president of France, to discuss the newly established funding agency for scientific research, the Caisse Nationale des Sciences, and she could not refuse. One of the first Caisse grants was awarded to the promising young Frédéric Joliot. The state-sponsored windfall would allow him to quit his sideline teaching job and devote himself totally to research.

With Irène still away, Frédéric took Hélène to l’Arcouest on vacation. “I wrote Irène to recommend she get a blood count as soon as she returns,” he informed Marie. “If you are in Paris then, please insist that she listen to me.” In other news, he said Hélène had formed a marvelous friendship with Charles Seignobos, the elderly Sorbonne historian hailed by the summer regulars in l’Arcouest as “le capitaine” of all sailing and social activities. Now Seignobos let the littlest member of the company gather flowers in his garden.

August took Irène back to her family and back to Brittany. “I have done a little bit of work, very little,” she wrote Marie from l’Arcouest, “but if we have bad weather, I think I’ll get better motivated.” She was planning the students’ projects for the coming academic year, matching their interests with their skills and experience.

The start of the fall term was to bring Dutch chemist Antonia Korvezee to the Radium Institute from the Technical University in Delft, where she had recently completed her doctoral degree and won a scholarship to further her education abroad. Although Irène did not keep a running count, Mlle. Korvezee would be the thirty-fifth woman to enter the Curie lab since Harriet Brooks found her way to the old Annex in 1906.

Marie, in Cavalaire, sent bonbons to Irène for her birthday, followed by a teddy bear and a construction set for Hélène’s birthday.

“I had a toy chest built for Hélène,” Irène reported while still in l’Arcouest in mid-September, “but I had it made a little too large. And the result is that Hélène, after putting her toys inside it, climbs in to play with them. Making off with the chest just then would capture the baby and all her belongings in one fell swoop.”

That same month saw the death of Kazimir Dluski, Marie’s protective “little brother-in-law” who had looked out for her during her student days at the Sorbonne, and who had shared Bronya’s life for forty years.

“My siblings are in reasonable health,” Marie wrote Ève from Warsaw, not long after the funeral. They lived “in a circle that tightens as they advance in age, and in which the loss of Uncle Dluski has left a sorrowful gap.” Bronya was coping with her grief by concentrating on her professional duties, readying the new radium institute and hospital. “What I fear most for her,” Marie said, “is the moment when she will need to curtail her activities, because then the past will come round to haunt her.”