After reading this book, you may ask yourself how to move forward. The eleven artists who are featured in this book have all been inspired by—and, in turn, influenced—other artists. The six images shown here only just begin to show the range of influences at play with these eleven artists. No matter how far along you may be on your personal artistic path, inspiration is sure to flow—in one direction or another.

Many of the artists presented in this book are instructors, and they always try to impart to their students to “make the work your own”—a difficult thing to do. There is the need to replicate the lessons to improve your skill, but at some point your voice must begin to be present in your work.

You have taken this journey with us. Now create your own journey! Find an artist in your area who works in polymer (or even another medium) and work on a piece together. Plan a meeting where you bring your own work and discuss what is most important to you about the piece and why. Work together and spend time apart to think about the piece and bring new and fresh ideas that push your design and your ability.

Search the Internet for a person or group that excites you. Collaborations can be done long distance! Start a piece, perhaps a focal bead, and send it on to another artist who might add supporting beads or maybe wirework. A third person could join all the pieces together. Each artist adds his or her vision, usually in surprising ways.

Join or host a swap—where a group of artists all make a set number of pieces of work centered around a theme. All the work is gathered by the person hosting the swap, and one piece of each of the other artists’ work is then returned to each of the participants. Evaluate how each of the artists interpreted the theme.

Attend everything you are financially able to. Find polymer and art conferences and retreats. Allow yourself to be immersed in those around you and what they are creating. Take note of artwork you see and query the artist who made it: What inspired them? Why did they choose certain colors? How did they solve problems they incurred while creating the piece? Ask them to discuss your work: How would they have done it differently? What might they have added or taken away to make the piece more successful? Making the effort to engage in a broad range of dialogues is bound to stretch and improve your work. Enjoy the journey!

Margaret Reid,

Sylvan, 2007; polymer, wire, paper, skewers, and pine cone; dimensions variable. Photograph by Laurence Winram. This piece was created during a weeklong workshop in France with Dayle and was inspired by the title of the course: “Discovering Ancient France.” Margaret, a colleague and friend of

Dayle Doroshow, is always thinking about how to do things differently. Dayle admires the cleanness of her art, the sense of adventure, and that she works with intention.

Karen Woods,

Out of Africa, 2006; polymer; 13 × 18 inches (33 × 46cm). Photograph by Karen Woods. Karen’s prizewinning necklace was inspired by African mudcloth that she was making at the time. Taking a cue from Sarah, whom she considers one of the premier caners in the polymer community, gave her the opportunity to work with complex caning—the technique that makes her heart sing. With a background in textiles and basket weaving, Karen shares an affinity with

Sarah Shriver for all sorts of repeat patterns.

When

Leslie Blackford looks at a piece that Scott has made, she is immediately transformed into a land of wonder. His work is so oddly unique and simply beautiful. Scott Radke,

Deer Series, 2005; mixed media; each 13 × 13 inches (33 × 33cm). Photograph by Scott Radke

Ron Lehockey, Hearts, 2011; polymer; dimensions variable. Photograph by Ron Lehockey. Ron is a general pediatrician in Louisville, Kentucky, who treats children with special challenges. In 2011 he reached seventeen thousand hearts. Ron takes several workshops each year. The techniques that he masters are quickly fashioned into his signature heart pins, donating all of the proceeds to a children’s charity. In looking at a pile of pins you can spot ones inspired by Jeff Dever, Sarah Shriver, Judy Belcher, and Lindly Haunani.

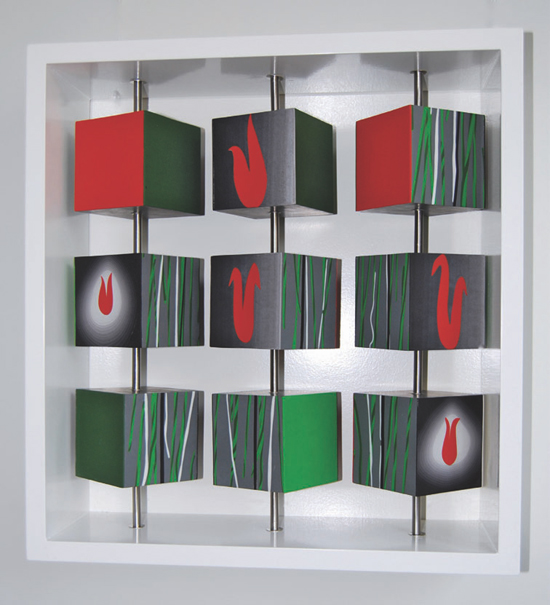

Alev Gozonar, Tulips, 2010; polymer, Plexiglas, metal, and wood; 24 × 24 inches (60 × 60cm). Photograph by Alev Gozonar Tulips is part of Alev’s cube collection, in which the cubes, turning on their own axes, have separate images on each side. The viewer is able to pick the images on the cubes and, therefore, is an active participant in the creative process.

Judy Belcher is intrigued by the movement in Alev’s work, but more important, the active participation by the public that it inspires. As an art form, polymer has the potential of moving into public spaces—it’s something that Alev has mastered in her home country of Turkey.

Rachel is one of the few polymer artists who has developed a entire body of work exploring screen printing. Seth Lee Savarick has long admired Rachel’s complex surface designs.

Rachel Carren,

Hokusai Cupola Brooch, 2010; polymer and acrylic pigment; 2⅜ × 2⅜ × ⅜ inches (6 × 6 × 1cm). Photograph by Hap Sakwa. Rachel’s brooch design is based on the idea of an architectural dome. Color scheme and patterning is after the work of the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849).