Lorne Michaels and SNL’s Creative Team

To translate NBC president Herb Schlosser’s three-page memo into a hit television series, Dick Ebersol, director of weekend late-night programming, hired thirty-one-year-old Lorne Michaels, whose experience in television as a comedy performer and writer/producer made him the ideal producer to get the new series off the ground. In a 1992 interview with Playboy magazine, Michaels explained why he was hired: “The head of NBC then, Herb Schlosser, said, ‘We’re looking for a show for young urban adults.’ Yuppies weren’t invented yet. I was a young urban adult. I knew that television had changed everything. There was no difference in what people knew whether they lived in New York, Los Angeles, or the heartland. So if I could bring what was already popular in records and movies to television—if I just did a show that I would watch—well, there were lots of people like me. There was nothing cynical about it; no clever scheme of outsmarting anyone.”

The eldest child of Florence and Henry Lipowitz, Lorne Lipowitz grew up in Toronto, Canada, where his first exposure to show business was the College Playhouse, a movie theater owned by his grandparents on College Street near the University of Toronto. After earning his bachelor’s degree in English from University College, University of Toronto, he pursued a career in broadcasting at CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Radio. He also performed on the air with his writing partner, Hart Pomerantz. The pair were then hired as staff writers on the short-lived NBC variety show The Beautiful Phyllis Diller Show (1968), and for a season on Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968–1973), for which Michaels received his first of many Emmy nominations. Michaels and Pomerantz also starred on their own sketch comedy series on Canadian television, The Hart & Lorne Terrific Hour (1971–1972). After going their separate ways (Pomerantz became an attorney), Michaels’s career took off when he was hired to write and produce three successful Lily Tomlin television specials, winning Emmys for writing in 1974 and 1976, the same year he took home statues for writing and producing season 1 of Saturday Night Live.

In his interview with the AAT, Ebersol recalled how he and Michaels spent February through mid-March of 1975 developing SNL while living at the Chateau Marmont, the same Los Angeles hotel where John Belushi would die of a drug overdose seven years later. When it was time to pitch their idea to the NBC brass, they wouldn’t allow Michaels in the boardroom because he was a producer for hire and not an NBC employee. So Ebersol gave them a rundown of the show and explained there would be a repertory company of players with a new guest host each week (he dropped the names of some of the people they had in mind—George Carlin, Richard Pryor, and Lily Tomlin). Two names had also been added as regular contributors to the show: comedian Albert Brooks, who was signed to make a short film each week, and puppeteer Jim Henson, who would be introducing a new breed of Muppet characters. Incidentally (and certainly not coincidentally), Henson and Michaels had the same manager, Bernie Brillstein, who, over the years, handled the careers of many SNL cast members, including Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, Gilda Radner, Martin Short, Dana Carvey, Adam Sandler, and David Spade.

As Ebersol recalled, his pitch to the executives played to “total silence.” When Herb Schlosser asked if anyone had anything to say, there was no response. Schlosser then turned to the head of research and asked for his opinion. He said the show would never work because its target audience would never come home by 11:30 p.m. on a Saturday night. Fortunately, he was wrong.

When it was time to hire talent for both behind and in front of the camera, Michaels assembled a group of performers, writers, and artisans who were relatively young by television standards. Most of them were under the age of thirty (the youngest cast members, Dan Aykroyd and Laraine Newman, were twenty-three when SNL debuted) and had an irreverent, subversive comedic style compared to the crop of family friendly prime-time variety shows like Cher (1975–1976), Tony Orlando and Dawn (1974–1976), and the long-running The Carol Burnett Show (1967–1978). Their comedic roots were in sketch and improvisational theater, and in the pages of National Lampoon magazine. Michaels appointed former Lampoon editor Michael O’Donoghue, better known to early SNL fans as “Mr. Mike,” as the show’s first head writer. Anne Beatts, the Lampoon’s first female editor, was one of three women hired as staff writers.

Many of the writers and cast members had worked together on National Lampoon–related projects. O’Donoghue was also the creator of The National Lampoon Radio Hour, a half-hour, syndicated weekly sketch comedy radio show that ran from November 1973 through December 1974 and featured Chevy Chase, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, and John Belushi, who succeeded O’Donoghue as the show’s creative director. SNL cast members also appeared off Broadway in two Lampoon stage shows in the early 1970s: National Lampoon’s Lemmings (1973) with Chase and Belushi, and The National Lampoon Show (1975) with Radner, Belushi, Murray, and his older brother, Brian Doyle-Murray, who joined the SNL family in 1979 as a featured player.

While Lampoon’s subversive sense of humor certainly influenced SNL’s comedic style, Michaels admitted he was not much of a Lampoon fan. In a 1979 Rolling Stone interview with Timothy White, Michaels stated, “there was a kind of male-ego sweat socks attitude” in Lampoon’s humor that “[I] never have really been a part of.” In the same interview, Michaels explained that Second City, the sketch comedy and improvisation theater troupe founded in 1959 in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood, had a more profound influence on SNL’s brand of humor. Most of the cast members had training in stage sketch comedy and improvisation: Dan Aykroyd and Radner were graduates of Second City in Toronto; Belushi and Murray hailed from Second City in Chicago; Jane Curtin was a member of the Boston improv group the Proposition; and Laraine Newman was one of the founding members of the Los Angeles–based improv group the Groundlings, whose alums boast a long list of SNL cast members, including Will Ferrell, Will Forte, Ana Gasteyer, Phil Hartman, Chris Kattan, Taran Killam, Jon Lovitz, Cheri Oteri, Chris Parnell, Maya Rudolph, Julia Sweeney, and Kristen Wiig.

The Creative Team

• Anne Beatts (writer) was the first female editor of National Lampoon and editor of two women’s comedy anthologies, Titters (1976) and Titters 101 (1984). She, along with Rosie Shuster, created characters like “the nerds,” Todd and Lisa (Bill Murray and Gilda Radner), perverted babysitter Uncle Roy (Buck Henry), and the sleazy entrepreneur Irwin Mainway (Dan Aykroyd). After her five years on SNL, for which she won an Emmy and a Writers Guild Award, Beatts created the CBS situation comedy Square Pegs (1982–1983), starring an unknown Sarah Jessica Parker, and was responsible for revamping The Cosby Show (1984–1992) spin-off A Different World (1987–1993).

• Al Franken and Tom Davis (writers) began their twenty-year-plus comedy partnership when they met in prep school in Minneapolis, where after college they joined Dudley Riggs’s Brave New Workshop. They performed comedy in Los Angeles and Reno before being hired as writing apprentices by Lorne Michaels, splitting a single salary of $350 a week. They also appeared semiregularly on SNL under the title The Franken and Davis Show. They departed the show after season 5, only to return together and separately several times beginning in the mid-1980s through the 2002–2003 season. They both received multiple Emmys for their work on the show and an Emmy for writing The Paul Simon Special (1977). Franken wrote and starred in Stuart Saves His Family (1995), a film vehicle for his popular recurring SNL character, Stuart Smalley (see chapter 23) and created and starred in the NBC sitcom Lateline (1998–1999). He is also the author of several books, including Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot and Other Observations. In 2008, Franken was elected to the U.S. Senate from his home state of Minnesota. Meanwhile, Davis, who cocreated the Coneheads with Dan Aykroyd, collaborated on the screenplay for the 1993 film. He later hosted Trailer Park (1995–2000) on the Sci-Fi Channel and in 2009 published his memoir, Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss: The Early Days of SNL from Someone Who Was There. Davis died of cancer on July 19, 2012.

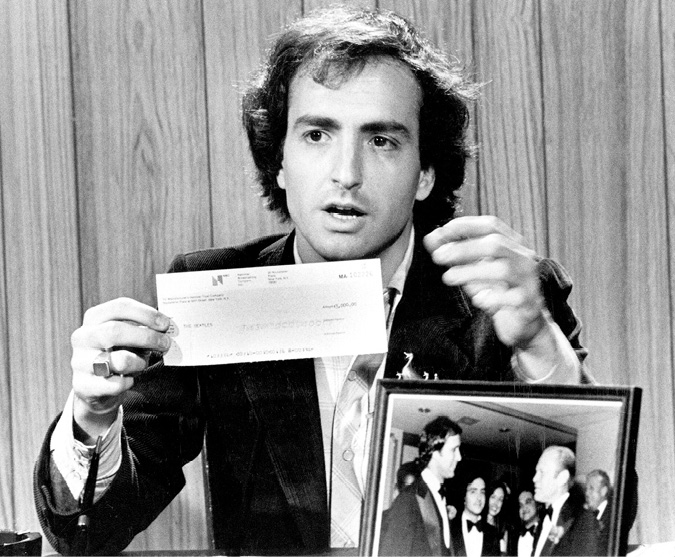

Television writer/producer Lorne Michaels, who was hired by NBC to create a new late-night comedy show, offers the Beatles a check for $3,000 to reunite on SNL (1.18).

NBC/Photofest © NBC

• Eugene Lee and Franne Lee (production and costume designers) are a former husband-and-wife design team best known for their work on Broadway. They both won a pair of Tony Awards for scenic and costume design for the 1974 revival of Candide. Eugene Lee, who has been the scene designer for over twenty Broadway productions, winning Tony Awards for Sweeney Todd (1979) and Wicked (2003), has been the production designer on over four hundred episodes of SNL. Franne Lee, who also won a Tony for her costumes for Sweeney Todd, left SNL after five seasons.

• Marilyn Suzanne Miller (writer) had no professional writing credits when the recent college grad made a cold call to writer/producer James L. Brooks (she doesn’t know why he took the call) and pitched her idea for an episode of Mary Tyler Moore (1970–1977), which led to a job as a junior writer on The Odd Couple (1970–1975). In addition to her five years on SNL, she wrote episodes of Mary Tyler Moore, Rhoda (1974–1978), Maude (1972–1978), and Welcome Back, Kotter (1975–1979). Her post-SNL credits include Cybill (1995–1998), Murphy Brown (1988–1998), and The Tracey Ullman Show (1987–1990), for which she won her third Emmy. Miller’s profile for the Paley Center for Media describes her work on SNL as “Marilyn pieces”—sketches that focused on character, rather than jokes, and infused “humor with poignancy.” Some of her most memorable sketches include “Slumber Party,” in which Gilda, Jane, Laraine, and host Madeline Kahn are young girls having a late-night talk about where babies come from (1.19); a sketch from an Emmy-winning episode in which host Sissy Spacek plays a newlywed whose husband (John Belushi) can’t perform in the bedroom (2.15); and “The Judy Miller Show,” in which Radner plays a hyperactive tween alone in her room who entertains herself (3.4, 3.17).

• Michael O’Donoghue (head writer), a.k.a. “Mr. Mike,” began his writing career as the author of dark, absurdist plays and illustrated books, including The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist (1968). He was one of the founding writers and later the editor of National Lampoon magazine. Lorne Michaels hired him as the show’s head writer, earning him two Emmy Awards for writing. O’Donoghue stayed with SNL for three years, but returned in 1981 when he was hired by the show’s new executive producer, Dick Ebersol, to save SNL after its disastrous sixth season. He only lasted eight shows. According to his biographer, Dennis Perrin, author of Mr. Mike: The Life and Work of Michael O’Donoghue, he was fired over creative differences, though he was rehired for the 1985–1986 season when Lorne Michaels returned to the show. As Mr. Mike he told “Least-Loved Bedtime Tales” like “The Enchanted Thermos” (2.6), “The Blind Chicken” (2.7), and, to fourteen-year-old guest host Jodie Foster, “The Little Train That Died” (2.9). During his tenure at NBC, O’Donoghue wrote, directed, and starred in a special for NBC, Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video (1979). Although it was slated to air in SNL’s time slot, the network demanded too many cuts, so it was released (and bombed) in theaters. His other acting credits include featured roles in Manhattan (1979), Head Office (1985), Wall Street (1987), and Scrooged (1988), which he cowrote with Mitch Glazer. O’Donoghue died in 1984 from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of fifty-four.

• Don Pardo (announcer) has been one of the voices of NBC since 1944. Prior to SNL he was best known as the announcer on several game shows, including the original Jeopardy! (1964–1975). Pardo has served as SNL’s announcer for all but one season (season 7, when he was replaced by Mel Brandt with Bill Hanrahan sitting in for Brandt for two episodes [7.7, 7.8]), and while viewers are more familiar with his voice than his face, Pardo did occasionally appear on camera. He participated in NBC’s “Save the Network” telethon (6.8) and came out from his announcer’s booth in 2008 to blow out his candles on his ninetieth birthday cake (33.5). In what is certainly an unusual collaboration, Pardo lent his voice to three Frank Zappa recordings, including “I’m the Slime,” which was performed on SNL (2.10). At the age of ninety-two, he was inducted in the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences’ Hall of Fame.

• Herb Sargent (writer) was a veteran television writer whose credits dated back to the mid-1950s when he wrote for Steve Allen (The Steve Allen Plymouth Show [1956–1960], The New Steve Allen Show [1961]) and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (1962–1992) early in its run. He was also a staff writer on the American version of one of SNL’s predecessors, That Was the Week That Was (1964–1965) (see chapter 5) as well as other comedy-variety shows and specials. Sargent also wrote numerous network specials, winning two of his six Primetime Emmys for writing and producing Lily Tomlin’s 1973 special, Lily. Sargent was on the writing staff of SNL as a writer and “script consultant” for a total of seventeen seasons (1975–1980, 1983–1995). In his interview with the Archive of American Television, Dick Ebersol described Sargent as one of the few “adults” involved in the show in its early years (director Dave Wilson and associate producer Audrey Peart Dickman were the two others). Sargent is credited as the one responsible for developing the Weekend Update segment with its first anchor Chevy Chase. At the time of his death from a heart attack in 2005, Sargent was president of the Writers Guild of America, East. Since then, an award bearing his name, the Herb Sargent Award for Comedy Excellence, has been given to James L. Brooks (2006), Lorne Michaels (2007), and most recently, Judd Apatow (2012).

• Tom Schiller (writer) is the son of veteran television comedy writer Bob Schiller (I Love Lucy [1951–1957], The Carol Burnett Show, Maude, and All in the Family). Before SNL, he wrote and directed a short documentary about the writer Henry Miller entitled Henry Miller Asleep & Awake (1975). During SNL’s first five seasons, he was a staff writer and contributed a series of memorable short films to SNL, including Don’t Look Back in Anger (3.13), La Dolce Gilda (3.17), and Java Junkie (5.8). His association with SNL as a writer and filmmaker continued through the 1980s into the early 1990s, winning him three Emmys. Schiller also wrote and directed the 1984 feature Nothing Lasts Forever, featuring Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and Zach Galligan.

• Howard Shore (musical director) first collaborated with Lorne Michaels when they were campers and later counselors at Camp Timberlane in Ontario. Shore was the musical director of The Hart & Lorne Terrific Hour and for the first five seasons of SNL, returning in season 11 as the show’s music producer. He composed the score for over fifty films, frequently collaborating with directors David Cronenberg, Martin Scorsese, and Peter Jackson. He is the recipient of three Academy Awards for The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) (Original Score), and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) (Original Score and Original Song, cowritten with Fran Walsh and Annie Lennox).

• Rosie Shuster (writer) is a Toronto native and a second-generation comedy writer. The daughter of Frank Shuster, of the legendary Canadian comedy duo Wayne and Shuster, she was on the writing staff of The Hart & Lorne Terrific Hour. In 1971, she married one of its stars (and longtime friend) Lorne Michaels. They next worked together on several Lily Tomlin specials and then on Saturday Night Live, where she was a staff writer for the first seven seasons and again in 1986–1988. Her other television writing credits include episodes of Square Pegs, The Larry Sanders Show (1992–1998), and the animated series Bob and Margaret (1998–2001).

• Dave Wilson’s (director) affiliation with NBC dates back to the 1960s when he worked on variety shows like The Bell Telephone Hour (1959–1968) and The Kraft Music Hall (1967–1971). Over the course of seventeen years, he directed over three hundred episodes of SNL, winning an Emmy for directing the second episode (1.2), hosted by Paul Simon. Wilson (affectionately known as “Davey”) was sometimes featured in cold openings and monologues that spilled over into the control room, where we saw him dressed as a bee (2.9), drunk with his crew on St. Patrick’s Day (4.15), and dead, only to miraculously wake in time to signal the engineer to roll the opening credits (2.15).

• Alan Zweibel (writer) was a joke writer for stand-up comedians when he was hired by Lorne Michaels to write for SNL. He is best known for writing the Samurai sketches and for Gilda Radner’s alter egos Roseanne Roseannadanna and Emily Litella. His friendship with Radner was the subject of his best-selling book Bunny Bunny: Gilda Radner—A Sort of Love Story. He was the cocreator and producer of It’s Garry Shandling’s Show (1986–1990) and cowrote the screenplays for Dragnet (1987), North (1994) (based on his novel), and The Story of Us (1999). He also collaborated with former SNL cast members Billy Crystal on his one-man Tony Award–winning show 700 Sundays (2004), and Martin Short on his autobiographical musical revue Martin Short: Fame Becomes Me (2006).