6

One Samurai, Three Coneheads, and a Pair of Douchebags

SNL in the 1970s (1975–1980), Seasons 1–5

Seasons 1–5 of SNL showcased a menagerie of off-the-wall characters, ranging from a family of aliens, to a pair of Czech wannabe playboys, to a couple of teenage nerds. When a certain character clicked with the audience, he or she was certain to become a permanent part of the show’s repertoire of recurring characters. Here are the most memorable characters, sketches, and moments from seasons 1–5. In the case of recurring characters, the number in parentheses indicates the episode in which he or she debuted.

Land Shark: “Candygram” (1.4)

Nineteen seventy-five was the year of the shark due to the release of director Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, which became Hollywood’s first summer blockbuster, earning over $100 million by mid-August and becoming the biggest moneymaker of all time. In season 1, SNL first parodied Jaws (1.4) with a sketch (entitled Jaws II) in which a “Land Shark” (Chevy Chase) knocks on the apartment doors of young, unsuspecting single females as the Jaws theme plays in the background. When they ask who it is, the shark mumbles a series of answers in a low tone (“Plumber” . . . “Flowers” . . . “Candygram”). The Land Shark made subsequent appearances, including a visit to host Louise Lasser’s dressing room door when she won’t come out (1.23), on Halloween night posing as a trick-or-treater (2.6), at the door of The Spirit of St. Louis when Charles Lindbergh (Buck Henry) gets too close to the water during his transatlantic flight to Paris (2.22), in the middle of a sketch that had no ending when Chase returned as host (3.11), at a woman’s door via a video monitor (when Chase hosted from Burbank) (8.1), and on the set of Weekend Update where he eats Tina Fey (27.2).

Emily Litella: “Never mind.” (1.5)

In her memoir, It’s Always Something, Gilda Radner revealed that Emily Litella was based on Mrs. Elizabeth Clementine Gillies (affectionately known as Dibby), who was her nanny for eighteen years. Throughout her life, Radner stayed in touch with Dibby, who, in March 1989, two months before Radner died of cancer, turned ninety-six years old.

Emily Litella debuted on SNL (1.5) as a guest on a talk show, Looks at Books, hosted by Jane Curtin. She is there to discuss her new book, Tiny Kingdom, which is part of her “Tiny Book” series. Two shows later (1.7), she delivers her first editorial reply on Weekend Update, speaking out against “busting schoolchildren” (as opposed to “busing schoolchildren”). Once anchorman Chevy Chase (or as Emily called him, “Cheddar Cheese”) corrected her and she realized her mistake, she smiled into the camera and simply said, “Never mind.” Jane Curtin (or as Emily called her, “Miss Clayton’), who anchored Weekend Update when Chase departs the show, is far less patient with Litella, who, after apologizing profusely, utters one final word—“Bitch.” Playing the role of the serious newscaster, “Miss Clayton” eventually demotes Emily to appearing as a dancing red and blue “N” (the current NBC logo) (3.8), though she returned to Weekend Update when “Cheddar” came back to guest anchor the news (3.11).

From the death penalty to the environment to television violence, Miss Litella came close to addressing some of the more important national and international issues of the 1970s:

“What is all this fuss I’ve been hearing about . . .”

• “Busting” (busing) schoolchildren (1.7)

• “Firing” (hiring) the handicapped (1.8)

• “Saving Soviet ‘jewelry’” (Jewry) (1.11)

• “Eagle” (Equal) Rights Amendment (1.12)

• “Canker” (Cancer) research (1.13)

• The “deaf” (death) penalty (1.15)

• Preserving natural “race horses” (resources) (1.16)

• The 1976 presidential “erection” (election) (1.17)

• “Violins” (violence) on television (1.19)

• “Crustaceans” (Croatians) hijacking a plane (2.1)

• Collecting money for “unisex” (UNICEF) (2.10)

• Making Puerto Rico a “steak” (state) (2.11)

• Endangered “feces” (species) (2.15)

• The “Sssssst” (SST—Super Sonic Transport) (3.8)

When actress Ruth Gordon hosted the show (2.12), she appeared as Emily’s equally eccentric sister, Essie Litella, who suggested burning tissues [issues] for Emily’s next editorial: “transcendental medication [meditation]” and equipping cars with “air fags [bags].”

“Word Association Test” (1.7)

The most memorable sketch of the early days of SNL was not written by a member of the writing staff but comedian Paul Mooney, who wrote for guest host Richard Pryor. It involves a Human Resources interviewer (Chevy Chase) giving a word association test to a job applicant for a janitor position (Pryor). The test starts off with word pairs one would expect on such a test. Chase says “fast” and Pryor says “slow.” But the test takes an unexpected turn when Chase begins to spout a series of racial epithets like “Tarbaby,” “Colored,” “Jungle bunny,” “Spade,” until he gets to the word “Nigger” (which he says). For every epithet, Pryor throws back white slurs like “Redneck,” “Cracker,” and “Honky.” The sketch delivers a powerful statement on institutionalized racism, something Mooney revealed in his autobiography, Black Is the New White, that he experienced during his week at SNL when he was cross-examined all week regarding his qualifications to write for the show.

As for Pryor, his manager’s advice not to accept a position as a rotating host on SNL was right on the money in light of the treatment he received from the network when he was given his own show after his successful appearance on SNL. The Richard Pryor Show (1977) was canceled after four episodes over creative differences between its star and the network, which is a polite way of saying standards and practices wouldn’t allow his material on the air.

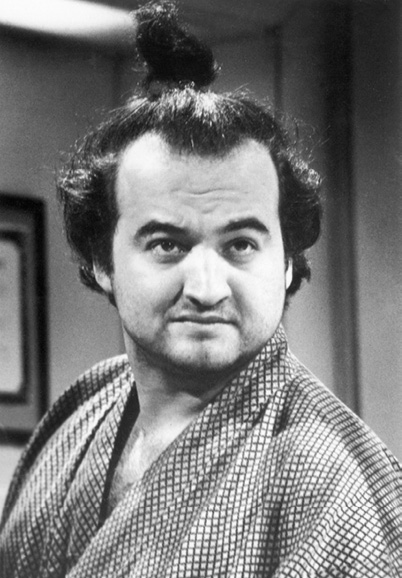

Samurai Futaba: “And now, another episode of Samurai [fill in profession here].” (1.7)

In addition to his rants on Weekend Update, John Belushi was given the chance to let loose by inhabiting the body of a Japanese samurai, one of the elite warriors who served the feudal lords of preindustrial Japan. The samurai practiced a strict code of conduct known as Bushido (“the way of the warrior”) that valued chivalry, loyalty, and honor. A samurai who was dishonorable, or may have brought shame upon himself, or would rather die with honor than fall into enemy hands performed a form of ritual suicide known as seppuku or hara-kiri by sticking a sharp blade in his abdomen. The samurai was popularized by Japanese cinema, particularly in the films of director Akira Kurosawa such as Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), and Yojimbo (1961), all of which starred Toshiro Mifune.

According to Judith Belushi Pisano, Mifune was the inspiration for her husband’s Samurai Futaba character. She told Michael Streeter, author of Nothing Lasts Forever: The Films of Tom Schiller, that John started to imitate Mifune after watching a Japanese film festival on television. “John would sit so close to the television,” Belushi Pisano recalled, “that when there was a close-up of Mifune, it appeared as if he was looking in a mirror—John would reflect what he saw.” She gave him a robe, a rubber band to put his hair up, and a clothes bar from a closet to use as a sword. Belushi auditioned for the show with the Samurai character playing pool, which is how writer Tom Schiller got the idea of “Samurai Hotelier.” Lorne Michaels, who worked on the sketch with Schiller, Chevy Chase, and Alan Zweibel, thought some people wouldn’t know what a “hotelier” is, so they changed the title of the sketch to “Samurai Hotel.” Zweibel wrote the remaining sketches, though Schiller provided him with a list of possible occupations for Samurai Futaba.

John Belushi as Samurai Futaba, a character modeled after the roles played by Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune in the films of director Akira Kurosawa, such as Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961).

NBC/Photofest © NBC

Each sketch works off the same premise: Samurai Futaba, who is dressed in traditional Samurai garb and has a limited understanding of the English language, has a different profession that’s incongruous with being a samurai warrior. In his sketch debut (1.7), Samurai Futaba faces off with a bellboy samurai (host Richard Pryor) over who is going to take a guest’s (Chase) bag up to his room. Belushi enjoys playing with his sword, using it to mime a golf putter and, like his audition, a pool cue. After some swordplay, Futaba insults the bellboy with the Japanese version of the traditional maternal insult (“Your momma-san”). The bellboy reacts by splitting the front desk in two with his sword. Samurai Futaba responds with the only English words we ever hear him speak—“I can dig where you’re comin’ from . . .”—as he takes the guest’s bag up to his room.

From season 1 to his final episode in season 4, Belushi repeated the role in a series of sketches featuring Buck Henry or another guest host as his customer or patient, who seems oblivious to the fact he’s a Samurai as he engages in small talk, which Futaba at times seems to understand. Belushi comically responds with grunts and Japanese gibberish, along with the raising of his bushy eyebrows and his sword. When the customer is displeased, Futaba kneels on the floor and pulls out his sword as if he is about to commit hara-kiri (at that point the customer usually assures him it’s all right). The sketch ends with Futaba raising his sword—with a freeze-frame and Don Pardo inviting us to “Tune in next week, for another episode of Samurai _______.” Some of the later episodes include:

• “Samurai Delicatessen” (1.10): When Henry orders a sandwich, Futaba is happy to cut it in half.

• “Samurai Psychiatrist” (3.6): When Henry calls him a quack, Samurai Futaba threatens to kill himself—and does.

• “Samurai TV Repairman” (3.20): Henry needs his television fixed to watch the basketball playoffs tomorrow. Futaba is ready to kill himself with a dagger because the person who inspected the defected machine, Inspector #68, is his momma-san. Futaba is relieved when Henry discovers the tag was upside down—it was Inspector #89.

• “Samurai Optometrist” (4.5): Henry breaks his glasses on a Sunday and needs a new pair. Futaba reaches for his sword when Henry calls him an optician instead of an optometrist.

• “Samurai Bakery” (4.20): Best man Henry needs a last-minute wedding for his brother’s wedding.

In “Samurai Stockbroker” (2.6), Belushi accidentally cut Henry’s forehead with the sword. Henry seems a bit dazed, but he continues the sketch by jumping out the window as if he is committing suicide. The next time we see Henry, he’s the moderator in a ’76 debate sketch between Jimmy Carter (Aykroyd) and President Ford (Chevy Chase), which is conducted like a beauty contest. Henry has a large bandage on his head—as does Chase when he comes out, and later Jane Curtin on Weekend Update. In Belushi Pisano and Colby’s biography of Belushi, Henry said he found it ironic that Belushi’s doctor happened to be in the audience. By the end of the show, almost everyone has a Band-Aid or bandage on his or her head (even Belushi).

Samurai Futaba also makes appearances during musical performances by Gordon Lightfoot (1.21) and Frank Zappa (2.10). Perhaps Samurai Futaba’s oddest and most unexpected appearance was in the pages of a Marvel Team-Up series comic book (#74) featuring Spider-Man and the Not Ready for Prime Time Players! vs. Silver Samurai. It’s set in Studio 8-H during a broadcast of SNL with Spider-Man creator Stan Lee as the guest host and Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson in the audience.

Godfather Group Therapy (1.9)

Participants in group therapy share their problems and feelings with each other in a “safe” environment under the supervision of a licensed therapist (played here by Elliott Gould). This group includes two people who live in very different worlds: The Godfather’s Vito Corleone (John Belushi, channeling Marlon Brando) and Sherry (one of Laraine Newman’s few signature characters), a girl from the San Fernando Valley who really loves being a stewardess “’cause she loves people.” When Vito starts talking about the grief the Tattaglia family is causing him, Sherry accuses him of blocking his true feelings and the group gets him to act them out, which he does—and performs Corleone’s heart attack at the end of the film. Belushi appeared again as Brando in a parody of The Godfather (3.5) and alongside another Brando imitator, host Peter Boyle. As the “Dueling Brandos,” they recite the actor’s most memorable lines from his movies (1.13).

Baba Wawa: “Not for Wadies Only” (1.18)

Gilda Radner’s imitation of Barbara Walters, better known as Baba Wawa, was first performed onstage in The National Lampoon Show. At the time, Walters was the host of a daily morning show, Not for Women Only (1968–1979), and Radner would watch the show before going to rehearsals. During a 1976 appearance with Lorne Michaels on a Canadian talk show, 90 Minutes Live, she told host Peter Gzowski that she noticed how she and Walters have “the same speech impediment and then all we had to do was change the L’s and R’s to W’s.” Radner perfected her impersonation with some help from some of the hair and makeup people at SNL who worked with Walters and told her “how to sit and all those secret things.”

In Gilda: An Intimate Portrait, biographer and friend David Saltman described the awkward first meeting between Gilda and Walters at a cocktail party in November 1976 at the Canadian consulate in honor of the Bicentennial. Gilda was nervous about meeting Walters, who seemed not to recognize Radner or her name. The comedian explained that she imitated her on Saturday Night. Walters said she had never seen it, but then said, “Oh, yeah, that’s right. Someone told me about that—that someone did an imitation of me.”

Walters proceeded to draw Radner into another room and asked her to do her imitation. She did and Walters responded, “I don’t see what so funny about it.” Radner managed to get a laugh out of her when she explained how she changed the L’s and R’s to W’s. Radner was still upset by the exchange and was worried she had perhaps damaged Walters’s credibility. David F. Smith, the former consul who introduced the two, later told Saltman, “Gilda . . . [was] so young and unworldly back then. Gilda was trying so hard to be kind. Barbara Walters did not have to be so cold, so rude to her.” “It was one of the few times Gilda, with her winning way,” observes Saltman, “did not bring out the best in people.”

Apparently the awkward meeting didn’t deter Gilda from imitating Walters. Baba Wawa made her SNL debut in April 1976 (1.18) with an appearance on Weekend Update to explain that she didn’t leave NBC for ABC because of her $5 million deal, but because of “Tom Snyduh. I simpwy cannot see his eahs” (1.18). Her later appearances were interviews with people from politics and entertainment, including “wiving wegend” Mahwena Dietrich [Marlena Dietrich] (Madeline Kahn) (1.19), Italian director Wena Wertmuller [Lina Wertmüller] (Laraine Newman) (1.21), Indian prime minister Indiwa Gandhi [Indira Gandhi] (Laraine Newman) (2.4), First Wadies Betty Fowd [Betty Ford] (Jane Curtin) and Woslyn Cawter [Rosalynn Carter] (Laraine Newman) (2.6), Henwe Kissingew [Henry Kissinger] (John Belushi) (2.8), Wichard Buwton [Richard Burton] (Bill Murray), (2.21), and Godziwa [Godzilla] (John Belushi) (2.16). Baba Wawa also appeared in a parody of My Fair Lady, in which Henry Higgins (Christopher Lee) and Colonel Pickering (Dan Aykroyd) try to help her with her R’s.

Super Bass-O-Matic ’76: “Wow, that’s terrific bass!” (1.17)

Dan Aykroyd played the perfect fast-talking television pitchman, who, in this in-studio commercial for a kitchen appliance known as the Super Bass-O-Matic ’76 demonstrates how you can prepare a bass “with no fish waste, and without scaling, cutting, or gutting.” You just put the whole bass (that’s right, the whole bass!) into what looks like an ordinary blender and turn it on. Then pour it into a glass like a milkshake. The Super-Bass-O-Matic ’76 also comes with ten interchangeable rotors, a nine-month guarantee, and a booklet, 1,001 Ways to Harness Bass. It also “works great on sunfish, perch, sole, and other small aquatic creatures.”

As one satisfied customer (Laraine Newman) attests, “Wow, that’s terrific bass!”

On the season 2 Halloween show, Aykroyd did a commercial for Bat-O-Matic (2.6). It’s the perfect alternative to a mortar, pestle or cauldron because it can cut, chop, slice, dice, mix, and blend anything, including plants, herbs, skin, hair, limbs and organs of all kind, and toads, lizards, newts, mice, rats and bats!

As one bat lover attests, “Wow! That’s great bat! And a great potion, too. I’m in love and my hives are cured!”

The Last Voyage of the Starship Enterprise (1.22)

SNL takes another jab at NBC in this popular and, for the time, ambitious, hilarious parody of Star Trek in which NBC executive Herb Goodman (Elliott Gould) comes aboard the Starship Enterprise and announces to the cast that they have been canceled due to poor Nielsen ratings (Mr. Spock [Chevy Chase] defines the Nielsens as a “primitive system of estimating television viewers once used in the mid-twentieth century”). When everyone admits that they have been defeated (even Mr. Spock gets emotional), Captain Kirk/William Shatner (John Belushi) refuses to abandon his ship and is left sitting alone on the dismantled set when he makes his final entry in his Captain’s captain’s log: “We have tried to explore strange new worlds, to seek out civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. And except for one television network, we have found intelligent life everywhere in the galaxy. [He gives the Vulcan salute.] Live long and prosper. Promise. Captain James T. Kirk, SC 937-0176 CEC.”

The Saturday Night Live book published in 1977 includes a letter from Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry to Elliott Gould, telling him that the sketch was “delicious”: “That is the proper word for it—imaginatively conceived and ably carried out with the kind of loose good humor that an entertaining parody demands.”

“The Right to Extreme Stupidity League” (2.10)

There’s nothing like live television—especially when a simple line flub can make a funny sketch even funnier. In this PSA for “The Right to Extreme Stupidity League,” two friends—Fern (Candice Bergen), the smart one, and Lisa (Radner), the stupid one—defend every American’s God-given right to be stupid. Lisa uses the expression “I’m so thirsty I could drink a horse” and pours her milk inside of her purse and says she is still thirsty. When Fern observes that she’s not too bright, she inadvertently calls Lisa by her name (“Fern . . . or whatever your name is”). Lisa then admits she is extremely stupid and proud of it. “You know,” tells the camera, “we all can’t be brainy like Fern here. . . .” Bergen can’t stop laughing (and neither can we). The flub, Bergen’s “deer-in-headlights” reaction to what she just said, and the way Gilda improvises around it without missing a beat, reminds us what we love most about live television.

The Coneheads: “We’re from France!” (2.11)

Created by Dan Aykroyd and Tom Davis, the Coneheads were inspired by the giant head statues carved from rock (better known as moai) that they saw on their holiday vacation to Easter Island. When Davis and Aykroyd returned to work in January, they wrote a sketch that eventually evolved into the Coneheads. In a 1978 Q&A with Franken and Davis entitled “Saturday Night Writers Strive for ‘Bad Taste,’” Davis credits Lorne Michaels with the idea of having Beldar Conehead (Aykroyd), his wife Prymaat (Jane Curtin), and their daughter Connie (Laraine Newman) live in suburbia (Parkwood, New Jersey, to be exact).

The Coneheads were an instant hit when they first appeared on the show (2.11). In “The Coneheads at Home,” Beldar and Prymaat explain to their teenage daughter Connie that twenty years ago the five high Masters of Remulak dispatched a fleet of Starcruisers to the earth’s solar system. They were instructed to land on Earth, take control of all the major radio and television communication centers, and introduce themselves: “People of Earth, we are the timekeepers of the planet Remulak. Your weapons are useless against us.” But Beldar lost the rest of the speech (containing the instructions, times, dates, places, and orders for the UN), and their flying saucer ended up in the bottom of Lake Michigan. So they bought a house in Parkwood, New Jersey (2130 Pineway Drive), changed their names to Fred and Joyce Conehead, and tell people they’re from France. Beldar now works as a driving school instructor. But the Coneheads sometimes had trouble concealing that they were from another planet, which is why they scare off an IRS agent (Steve Martin) (2.14) and run in horror themselves from their next-door neighbors’ house, the Farbers’, at the sight of a hairdryer (2.17).

The humor in the Coneheads sketches lies in how no one seems to notice they are not from this world coupled with their inability to fully assimilate, which is evident by the names they give to objects used by humans (a vacuum cleaner is a “particle collector,” the kitchen is a “food preparation chamber”) and the foods we consume like bacon and eggs (“shredded swine flesh and fried chicken embryos”) and pizza (“starch disks with vegetable matter and lactate extract of hoofed mammals”). Still, they somehow manage to win on Family Feud (3.9).

The Coneheads were also featured in Cone Encounters of the Third Kind, a parody of Close Encounters (1977) with host Richard Dreyfuss playing Roy Neary (his role in the film). Neary constructs a cone-shaped object, which leads him to the Coneheads’ house and then on to Remulak with the High Master (John Belushi).

“Just keep telling them we’re from France!”: Prymaat (Jane Curtin, left) and Beldar (Dan Aykroyd) explain their family history to daughter Connie (Laraine Newman).

NBC via Getty Images

Fourteen years after their debut on SNL, the Coneheads landed on the big screen with Aykroyd and Curtin reprising their roles as Beldar and Prymaat (see chapter 23).

Mardi Gras Prime-Time Special: “Mardi Gras is just a French word meaning ‘No Parade.’” (2/20/77)

At the start of the second season, Lorne Michaels announced that he would be taking SNL on the road and broadcast from Princeton University on October 16, 1975, and Georgetown University’s gymnasium two weeks later on Saturday, October 30, 1976, two days before the November 2 presidential election. “This will be our last chance to influence the November 2 election,” Michaels told Tom Zito of the Washington Post, “Basically our audience is college anyway, so the decision was made to try some shows on the road that rely on new video techniques—mini-cameras and a lot of hand-held stuff.” Less than two weeks later, the Post reported that all remote broadcasts from college campuses were called off. The unofficial reason was “technical problems,” though costs were most likely a factor.

The following February, Michaels did take his show on the road to New Orleans for a live, prime-time special from Mardi Gras, which aired on NBC on Sunday, February 20, 1977. The episode opened with Dan Aykroyd as President Jimmy Carter sitting on the top of a statue of Andrew Jackson in Jackson Square while First Lady Rosalynn Carter (Laraine Newman) stands below begging the president to come down. The segments that followed, shot both inside and outside at various locations around the city, featured musical performances by Randy Newman (“Louisiana 1927” and “Marie”) and the New Leviathan Oriental Fox Trot Orchestra (“Rebecca Came Back from Mecca”) from the Theatre of the Performing Arts; Laverne and Shirley stars Penny Marshall and Cindy Williams reporting from the Krew of Apollo drag ball; Eric Idle reporting on the crowd’s reaction to the festivities from an empty café; two films by Gary Weis, and comedy bits by Radner as Emily Litella and Baba Wawa, who interviews this year’s King of Bacchus, Henry Winkler; Aykroyd as Tom Snyder; John Belushi as Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire; and Paul Shaffer singing “The Antler Dance” while Mr. Mike shows the crowd how it’s done. Surprisingly (or maybe not), Garrett Morris, a New Orleans native, received minimal airtime. He hoped Gary Weis would shoot a segment in which he sang a song he had written, “Walking Down Bourbon Street,” about returning to his hometown, but it was never shot. Still, Morris was a hospitable host; the cast and crew were all invited over to his Aunt Audrey’s house for dinner.

The Mardi Gras episode was a great idea in theory, but as Lorne Michaels recounted to Mark Lorando in a 2008 article for the New Orleans newspaper the Times-Picayune, logistical difficulties, particularly with millions of drunken revelers in the streets, caused transportation problems that prevented everyone getting to and from where they needed to be.

But perhaps the biggest snafu was the last-minute rerouting of the Bacchus Parade due to an emergency on the route, leaving Buck Henry and Jane Curtin, who were sitting above the crowd at Canal Street and St. Charles Avenue, ready to provide the commentary as the parade went by, with nothing to do. Michaels considered them the show’s safety net. If a sketch wasn’t ready to start, they could always cut back to Henry and Curtin, which they did anyway. The pair were seated on the top of shaky scaffolding, and the revelers down below were hurling beads, doubloons, and bottles at them. “We had a writer, we had a sound guy, and we had a camera man, and we had a production assistant,” Curtin told Lorando, “and we had no security. So getting down off the scaffolding was almost as much fun as being on the scaffolding. They had to call in retired detectives . . . a lovely older gentleman came and literally carried Buck and me through the crowd. It was terrifying. Just terrifying. The Day of the Locust. And everybody chanting your name. It was scary.” Curtin did manage to deliver the evening’s punch line before the credits rolled: “The parade has not been delayed. It doesn’t exist. It never did. ‘Mardi Gras’ is just a French word meaning ‘No parade.’ Good night.”

With the exception of Newman and the New Leviathan Orchestra, who were far from the chaos outside, the show’s entertainment value had less to do with its comedic content and more to do with the fact it was live and you really didn’t know what was going to happen. There was the occasional technical mistake when the show was broadcast on its home turn in Studio 8H, but these tended to be very isolated moments. In this instance, the whole entire show felt like you were watching a powder keg that could blow at any minute.

The following day, the Times-Picayune’s Sandra Barbier reported that both the newspaper and the local NBC affiliate, WDSU, received phone calls complaining about the episode. “Everyone was expecting so much, it was a disappointment,” observed one New Orleans native. “People in other parts of the country probably didn’t understand what it was all about.” One caller to the Times-Picayune sounded more like a New Yorker than a Southern when she told the paper “NBC raped New Orleans.”

Leonard Pinth-Garnell: “That really bit it!” (2.15)

So-called high culture was skewered in a series of sketches that featured really bad plays, musicals, films, and short performance pieces. Our host is tuxedo-clad Leonard Pinth-Garnell (Dan Aykroyd), who introduces the evening’s presentation and assures us that what we are about to see is “Stunningly bad!” Bill Murray, featured as a regular player in each piece, is introduced as “our very own, Ronnie Bateman.” Pinth-Garnell usually ends each episode with his one-line review, an introduction of the players, and, finally, the ceremonial tossing of his program into the garbage can. Some of the exceptionably bad performances include:

• Bad Playhouse presents The Millkeeper (2.15) by Dutch writer, Jan Worstraad (“one of the worst of the new breed of bad Dutch playwrights of the Piet Hein School”)

The scene depicts the inner torment of a bride who lives in a windmill with her husband and sister, who is the literally in the clutches of Death (played by Ronnie Bateman [Murray]).

• Bad Cinema presents Ooh-la-la! Les Legs (2.18) by Henri Heimeau

Pinth-Garnell assembles a distinguished panel that includes Italian director Lina Wertmüller (Newman) and Truman Capote (Murray) to comment on this terrible film that consists of footage of a couple doing the twist in the streets of Paris. At the start of the sketch, Aykroyd appears to be looking around for Newman, who arrives late for the sketch and apologizes (in character).

• Bad Opera: Die Goldenklang (The Golden Note) by Friedrich Knabel (3.2)

A maiden named Mazda (host Madeline Kahn) is chosen by the gods to sing the golden note, which, if she sings, she will die. The opera is seldom performed because once Mazda reaches the “Golden Note,” she gets larynx lock (she sings the note forever), and must be taken away by the paramedics.

• Bad Musical: Leeuwenhoek by Hans Van der Scheinen (3.7)

Performed by the service staff of the Glendale Hospital for Wrist Disorders, this awful old-fashioned musical is about Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek (Pinth-Garnell refers to him as “Frederic Leeuwenhoek”), the Dutch scientist (played by Belushi) who contributed to the development of the compound microscope. The show originally ran “very Off-Broadway” in 1953 and closed in two and a half minutes.

• Bad Conceptual Art: Pavlov Video Chicken I by Helen Trouva (3.20)

A 378-hour conceptual piece first performed in 1965 at the Lifespace Galleries in Los Angeles. Written by and featuring Helen Trouva, it juxtaposes Zen poetry on video (a close-up of Newman’s lips as she recites poetry) and a woman (Radner, as Trouva) dancing like a chicken for 378 consecutive hours. There is a close-up of an eye (of Garrett Morris) on a second video screen. “Stunningly pointless,” Pinth-Garnell concludes. “Absolutely no meaning whatsoever. Really sucks.”

Twenty-nine years later, Leonard Pinth-Garnell (Aykroyd) returned to Studio 8H to present a new installment of Bad Conceptual Theatre, written by a group of chimpanzees. Anyone familiar with the Bad series got the joke when Chris Kattan was introduced as Ronnie Bateman Jr.

Nick the Lounge Singer: “Ah . . . Star Wars! Nothing but Star Wars!” (2.19)

Bill Murray revived a character from his Second City days, an untalented singer named Nick who performed in out-of-the-way, hole-in-the-wall lounges. Nick overcompensates for his lack of talent by trying to make each song his own by doing his variations of the lyrics to songs or inventing lyrics to movie theme songs with no lyrics.

Nick’s last name also changes with every sketch depending on the season and/or the venue. Here are some of his most memorable gigs:

• Nick Summers (2.19), from the Zephyr Room, at the beautiful Breezy Point Lodge at Lake Minnehonka, sings “I Write the Songs,” “Happy Anniversary” (to Mr. and Mrs. Gunnar Alquist [John Belushi and Gilda Radner] from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin), and “Sing.”

• Nick Winters (3.10), from the Powder Room, at a ski lodge on beautiful Meatloaf Mountain, sings the themes to 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars, “Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue,” and “That the Way (I Like It).”

• Nick Springs (3.19), from the Honeymoon Room at the Pocomount resort sings “I Love to Love You Baby,” “Poison Ivy,” “Hava Nagilah,” and the “Theme from Close Encounters of the Third Kind.”

American Dope Growers Union: “Look for the union label” (2.20)

Founded in 1900 in New York City, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was one of the country’s largest labor unions and the first to be comprised of a majority of female members. In the 1970s, the ILGWU released an ad campaign in which its members sing “Look for the Union Label,” a song that urges consumers to buy American at a time when manufacturing jobs were being lost to shops overseas. The commercials featured actual members of the ILGWU, mostly female and of all ages and races, who would come together and sing the song as an expression of solidarity.

In 1977, while the ILGWU commercials were airing, Saturday Night Live did their own version in support of another union that suffers whenever someone buys foreign over American-made. A representative of the American Dope Growers Union (Laraine Newman) tells us that every time you buy pot from Mexico or Colombia, you are putting an American out of work. “We have had a pretty hard time on our own,” she says, “but with the union we can lead decent lives and stay off welfare. That’s MY union, and that’s what our union label stands for.” She holds up a bag of pot with the Union’s sticker on it and begins to sing. She is soon joined by an enthusiastic group of pot growers (played by the cast members, members of the writing staff, and assorted extras). They begin to sing: “So look for, the Union label, when you are buying your joint, lid or pound.”

This is an example of what certain critics like to refer to as “drug humor.” After all, this was the 1970s, and most of the cast, the writers, and everyone else associated with the show both above and below the line, along with the audience were getting stoned (probably before, certainly during, and most likely after the show). As Hill and Weingrad so eloquently put it, “The image of a bunch of heads on Saturday Night Live putting together a show for the heads out there in TV land was definitely a large part of the show’s appeal. Saturday Night became in many respects, a passing of the communal joint around a circle that spanned, through television, the entire country.”

The comic bits about dope (mostly marijuana as cocaine would not become the drug of choice until the 1980s) were common, yet they never really dominated the show’s humor. The basic joke was that drugs were prevalent backstage. During host Eric Idle’s monologue (4.8), he wanders backstage to the writer’s lounge where sitar music is playing and the writers are either unconscious or smoking a hookah. John Belushi, who is at the center of most of the jokes, gives an editorial on Weekend Update (3.1) about the decriminalization of marijuana. He returns from Durango, Mexico, where he awarded a $2,500 scholarship on behalf of Weekend Update to a young aspiring journalist who is illiterate—but has some good connections (3.1). In another sketch, Belushi, dressed in a Cub Scout uniform, sits with host Minnesota Vikings quarterback Fran Tarkenton (2.13), who does a PSA for “Community Appeal,” which is helping unfortunates like John whose mind has been destroyed by drugs. Belushi later shares one of his killer joints with the “Anyone Can Host” contest winner, eighty-year-old Miskel Spillman (he told her it was a French cigarette) (3.8). When she appears onstage for her monologue, she’s flying and clutching onto a bowl of fruit from her dressing room.

The Festrunk Brothers: “Two wild and crazy guys.” (3.1)

“Two wild and crazy guys!”: The “smooth-talking” Festrunk Brothers, Georg (Steve Martin, center) and Yortuk (Dan Aykroyd) are getting nowhere with three single ladies played by (left to right) Gilda Radner, Laraine Newman, and Jane Curtin.

Dan Aykroyd paired up with Steve Martin for a series of sketches in which they played the Festrunk Brothers from Czechoslovakia, from which, as Georg (Martin) explains it in their debut (3.1), he and his brother Yortuk (Aykroyd) escaped “during the ’75 riots, by throwing many rocks at a Russian tank.” “A Wild and Crazy Guy,” was one of Steve Martin’s popular catchphrases and the title of his 1978 Grammy Award–winning comedy album. According to writer Marilyn Suzanne Miller’s bio for the Paley Center for Media (she was honored, along with Anne Beatts and Rosie Shuster, as part of their “She Made It: Women Creating Television and Radio” series), Aykroyd was inspired by Martin’s catchphrase and collaborated with her to create this pair who had successful careers back at home (Georg claims they had medical degrees) and were now selling decorative bathroom fixtures. The joke is that they are totally clueless when it comes to attracting American women (sorry, American “foxes”) because they look so ridiculous in their mismatched tight plaid shirts and slacks (“which give us great bulges!”) and the way they toss around American expressions like “You and what army?”

In his book Saturday Night Live: Equal Opportunity Offender, William Clotworthy, who worked for NBC’s Broadcast Standards Department, recalled that NBC received a letter from a Czechoslovakian special-interest group who “were very displeased and insulted by the presentation of two men as being refugees from Czechoslovakia. These individuals were two characters of a very low capability, skill, and moral values. They did not know how to dress properly and how to behave. Their English was very poor and what was presented to the TV audience as the Czech language was nothing but a mockery of our native tongue.” They demanded an apology and threatened to boycott the network. In their response, NBC explained that the Festrunk brothers “had never been recognized as insulting” and “the humor derived not from ethnicity but from their unfamiliarity with American customs and slang. Thus the satire was directed at the American character; i.e. the male breast emphasis, sexual emphasis, and the like.”

Twenty years after Georg and Yortuk were first seen swinging across their bachelor pad, the Festrunk Brothers appeared alongside the Roxbury Guys (Will Ferrell and Chris Kattan) (24.1), which coincided with the release of the feature film, A Night at the Roxbury. Their most recent appearance (38.16) was a game show parody, It’s a Date, in which contestant Judy Peterman (Vanessa Bayer) had to choose between Bachelor #1 (Bobby Moynihan), an ordinary guy; the “Dick-in-a-Box” guys (Justin Timberlake and Andy Samberg); and Georg and Yortuk Festrunk (Steve Martin, Dan Aykroyd). She rejects Bachelor #1, but is charmed by the others and decides to choose all four of them.

Things We Did Last Summer (10/28/78)

This odd collection of short documentaries (actually more like “mockumentaries”) directed by Gary Weis and written by Don Novello shows us what the Not Ready for Prime Time Players did over their summer, including Gilda Radner giving tours of her apartment, the Blues Brothers (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd) going on tour, Garrett Morris posing for lawn jockeys, Laraine Newman taking a tropical vacation, and Bill Murray playing minor-league baseball. The special is included on the SNL season 3 DVD set.

Roseanne Roseannadanna: “It’s always something!” (3.9)

Like Emily Litella, frizzy-haired Roseanne Roseannadanna did not make her Saturday Night Live debut on Weekend Update but in a “graveyard sketch” (the last sketch of the night)—a PSA for “Hiring the Incompetent” (3.4). Roseanne gives a short testimonial about how she was fired from her job making burgers at Burgerland because customers complained about human hair in the burgers (“What was I supposed to do, wear a bathin’ cap to work? . . . Besides, there’s a lot worst things that could be in burgers!”)

Later that season, Roseanne Roseannadanna joined Weekend Update as a correspondent. She began each report with a letter, usually from Mr. Richard Feder from Fort Lee, New Jersey, who asked questions about UFOs (“Do you believe in UFOs? Have you ever seen a UFO?”) (3.19), Studio 54 (“Why is it so hard to get in?”) (4.1), quitting smoking (“I’m cranky and I have gas. What should I do?”) (4.6), and depression over the holidays (“. . . I feel like hell! What should I do?”) (4.9). After making a crack about Mr. Feder and New Jersey (“Mr. Feder, you ask a lot of questions for someone from New Jersey!”), she answered the question by launching into a long diatribe that was completely off the topic and always included something disgusting, like warts and fever blisters (3.11) or toilet paper stuck to the bottom of Princess Lee Radziwill’s shoe (4.9) or a wet spot on Yves St. Laurent’s white pants (5.2). When an exasperated Jane Curtin tells her she’s making her sick, Roseanne delivers her catchphrase: “Well, Jane, it goes to show you—it’s always something.”

Roseanne Roseannadanna’s monologues were written by Alan Zweibel, who worked closely with Gilda Radner during their time together on the show. Mr. Richard Feder was also the name of Zweibel’s brother-in-law, who did live in Fort Lee, New Jersey. At the time, many people believed Roseanne was named after a local ABC New York newscaster, Rose Ann Scamardella, who was nothing like Roseannadanna in her demeanor. But in his profile of Radner for Rolling Stone, Roy Blount Jr. said the comedian’s name grew out of the rhyming song “The Name Game.” As Radner explains it, Roseanne Roseannadanna was meant to counteract “all these women reporting the news on TV; they always look like they’re so frightened to lose their job. You know they’re saying, ‘We’re women and have credibility to report the news, we don’t go number two, we don’t fart’ . . . And Roseanne, she’s a pig.”

The character is also the author of Roseanne Roseannadanna’s “Hey, Get Back to Work!” Book, published in 1983 by Long Shadow Books. The preface to the book is 100 pages long, and, like her reports on Weekend Update, it has nothing to do with the topic suggested by the title. Instead, it’s filled with personal information and stories of her family history. By the time she’s ready to discuss how to get, keep, lose, and get back the job you lost, she’s run out of pages. A letter from her publisher appears on page 11 in which he explains that due to “rising production costs” it would be “financially impractical” to allow her book to go beyond 100 pages. “As disappointed as I am,” he adds, “I can’t help but feel that had more thought been given to the body of the book than to the compelling, yet indulgent, preface, this situation would have never arisen.”

As Roseanne Roseannadanna would say, “It’s always something.”

“It’s always something”: Roseanne Roseannadanna (Gilda Radner, left) enjoys pushing all of Weekend Update news anchor Jane Curtin’s buttons with news commentaries that always go off topic.

NBC/Photofest © NBC

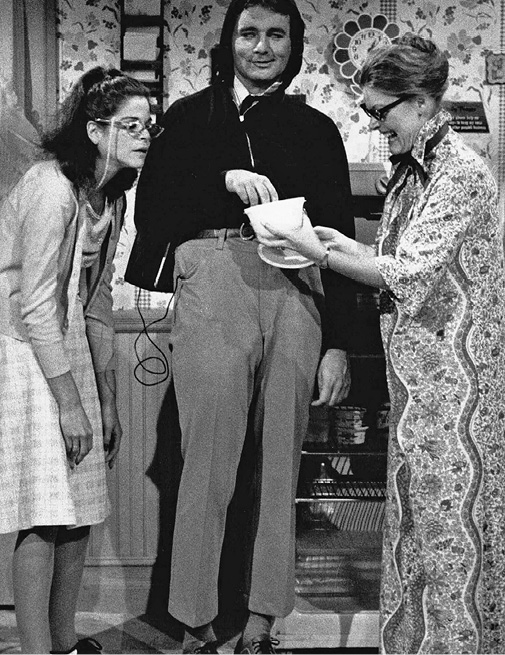

Lisa Loopner and Todd DiLaMuca: “Noogie Patrol” (3.10)

If you felt like a nerd, were called a nerd, or were a nerd in high school, you probably felt a little better about yourself when you first laid eyes on Lisa Loopner (Gilda Radner) and Todd DiLaMuca (Bill Murray). The way they dressed (Lisa with glasses, Todd with his pants pulled up high over his waist), the expressions they used (“Pizza face!” “Noogie Patrol”), and their awkward behavior were all nerdy to the nth degree, yet there was something endearing about this pair—maybe because they seemed quite content with their own nerdy existence and didn’t seem to care what other people thought of them. Or maybe it was the chemistry between Radner and Murray, who were apparently romantically involved sometime during their years on SNL. Todd teased and pursued Lisa, who was saving herself for her one true love—composer Marvin Hamlisch, whom she paid tribute to in her piano recital onstage at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York during her 1979 one-woman show, Gilda Radner—Live from New York (see chapter 23).

“Thank you, Mrs. Loopner”: Todd DiLaMuca (Bill Murray) charms Mrs. Loopner (Jane Curtin, right) as Lisa (Gilda Radner) looks on.

Todd and Lisa were first introduced (3.10) as “Pizza Face” (Todd) and “Four Eyes” (Lisa), respectively, who, along with their friend Spazz (guest host Robert Klein), appeared on a radio show to promote their newly released “nerd rock” album, Trying Desperately to Be Liked. (“We’re an idea whose time has come,” Lisa tells DJ Larry Duggan [Dan Aykroyd].) Unfortunately, no one calls in to claim a free copy. Lisa and Todd next appear as authors on the talk show Looks at Books (3.13) to discuss their new book, Whatever Happened to the Class of ’77? Inspired by the 1976 nonfiction best seller What Really Happened to the Class of ’65? in which authors Michael Medved and David Wallechinsky traced what happened to members of their high school class, Todd and Lisa’s book traced what’s happened to their graduating class since last June.

The next time we see Todd and Lisa they are inexplicably back in high school, entering their “Dialing for Toast” experiment at the science fair (3.18) and going to the prom (3.20). Todd even borrows his equally nerdy older brother Milt’s (Richard Benjamin) apartment in order to seduce Lisa (4.16). Fortunately, Mrs. Loopner’s “Parents Without Partners” was canceled and arrives in time to interrupt the festivities (Mr. Loopner, who invented the Slinky, was dead—“he was born without a spine, so it was just a matter of time.”). The sketch was one of the comedy highlights of the fourth season. Lisa can’t stop laughing, though it’s not entirely clear if it’s Lisa or Radner who is laughing at Todd’s attempt to get her drunk on Mateus Sparking Rosé.

The Olympia Café: “Cheezburger, Cheezburger” (3.10)

The setting is a greasy spoon diner owned by an impatient Greek named Pete Dionasopolis (John Belushi) with only three items on the menu—cheeseburgers, chips, and Pepsi. His staff are all members of his family: George Dionasopolis (Dan Aykroyd), his first cousin, whom he treats like a brother, grills the cheeseburgers; Sandy (Laraine Newman), his only waitress, is his second cousin, whom he treats like a first cousin; and Niko (Bill Murray), who works behind the counter, is his third cousin, whom he treats like a fourth. Niko only knows one word of English—cheeseburger. According to Pete, Niko is vlahos (that’s Greek for stupid). Gilda Radner plays a loyal customer who seems totally unfazed by the goings-on (and she usually orders a cheeseburger, Pepsi, and a bag of chips to go).

Writer Don Novello, who plays Pete’s brother, Mike Dionasopolis, who works in the back, modeled the Olympia Café after the Billy Goat Tavern, a real restaurant in Chicago established in 1934. In Live from New York, Novello recalled, “I used to go down there all this time . . . just to hear these guys going, ‘Cheezburger cheezburger cheezburger.’” In Judith Belushi Pisano and Tanner Colby’s Belushi: A Biography, Novello explained how “the owner was an old Greek guy who would hit you in the head with a cane when you walked in and yell ‘Get a haircut!’.” He had also brought his cousins over from Greece one at a time to work for him. The proprietors of the Billy Goat are grateful to Saturday Night Live for putting them on the map.

Novello believed that Belushi, the son of an Albanian immigrant, “really understood the working-class immigrant mentality.” The name of the restaurant was also changed from the Pyreaus Café because Belushi’s father owned a restaurant named the Olympia.

It’s basically a “one idea” sketch—the Olympia only serves cheeseburgers, and every time someone says the word (pronounced “cheezburger”), George thinks it’s an order and throws another patty on the grill. A customer comes in and orders something only to discover there’s no tuna, just cheezburgers; no fries, only chips; and no grape, orange, or Coke—just Pepsi. If they run out of cheeseburgers (3.10), they might serve you eggs, but scrambled, not “over lightly.” Over the course of seasons 3 and 4, the Olympia hires a new waitress (Jill Clayburgh), who has a meltdown her first day on the job (3.14); gets a makeover when Pete is away in Greece (the new waitress is Garrett Morris in drag) (4.1); and switches from Pepsi to Coke when he gets a good deal from a Coca-Cola salesman (Walter Matthau) (4.7). In our final visit (and Belushi’s final show), a suspicious fire (caused by “sparks”) has destroyed the Olympia Café and, unfortunately, his insurance policy is void because Niko had been living in the back room. A despondent Pete says the only thing they can do now—because they are Greeks—is dance!

Chico Escuela: “Baseball been berry, berry good to me.” (4.5)

Compared to his castmates, Garrett Morris didn’t play many recurring characters, but he is best remembered for playing former all-star for the New York Mets Chico Escuela (he was originally introduced as a former Chicago Cubs shortstop and second baseman). Although he has been playing ball in the United States for many years, Chico, who hails from Santo Domingo, has yet to master the English language. He’s best known for two phrases he would utter over and over, “Baseball been berry, berry good to me” and “Keep your eye on the ball.” Created by writer Brian Doyle-Murray for a sketch about a meeting of St. Mickey’s Knights of Columbus (4.5), Chico Esquela was based on Manny Mota from Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, whose career spanned twenty years (1962–1982), twelve of which were playing for the Dodgers (1970–1982). In an interview with the AAT, Morris explained that Chico was actually “a compilation of a whole lot of those guys” but he was really trying to capture the “whole energy” of Brazilian footballer Pele, who had retired in 1971 but maintained a high public profile throughout the 1970s.

For the remainder of season 4 and continuing into season 5, Chico was added to the Weekend Update, in which he gave the sports report, which consisted mostly of his two favorite phrases.

Julia Child: “I’ve cut the dickens out of my finger!”(4.8)

In what is considered his most memorable moment on SNL, Dan Aykroyd donned drag as Julia Child (4.8) in a takeoff of her cooking show The French Chef. While preparing a holiday feast, Child slices her finger and the blood starts to heavily gush out (“Oh, God, it’s throbbing!”). She instructs her audience on what to do in such an emergency (“If you are too woozy to tie the tourniquet, you might call emergency help!”), but eventually loses consciousness as the blood continues to drain from her hand. The sketch is shocking because there is such an excessive amount of blood and hilarious because of Aykroyd’s performance, particularly as Child begins to lose consciousness and begins to mutter about her childhood.

Lord and Lady Douchebag: “Just some salt and vinegar, thank you.” (5.20)

It’s the final show of the season and the final show for the writers and cast, so it was one final opportunity to push the limits of good taste with a Monty Python–esque sketch set in 1730 in Salisbury Manor. Lord Salisbury (Harry Shearer) is hosting a party for aristocrats, all of whose names, like their host’s, would one day be part of the English vernacular: Lord and Lady Wilkinson (Jane Curtin and Tom Davis) (he is carrying two swords, like the stainless steel razor blades made by Wilkinson Sword); the Earl of Sandwich (Bill Murray); Lord Worcestershire (Jim Downey); and, finally, Lord and Lady Douchebag (Buck Henry and Gilda Radner). You can tell Harry Shearer, Bill Murray, and Buck Henry are having fun repeatedly saying “Douchebag” on television (“Spoken like a true Douchebag!”).

The sketch concludes with Lord Douchebag walking outside into the garden with Lord Salisbury and the Earl of Sandwich to explain his new invention inspired by his wife that will immortalize the Douchebag name.

Lord Salisbury (Harry Shearer, far left) chats with his guests Earl of Sandwich (Bill Murray, second from left) and Lord and Lady Douchebag (Buck Henry and Gilda Radner) (5.20).

NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images