19

“And Here’s a Short Film By . . .”

SNL’s Original Shorts

Since its debut in 1975, Saturday Night Live has showcased an eclectic mixture of over three hundred narrative, nonfiction, and animated film and video shorts. The majority of shorts were produced specifically for SNL by a series of filmmakers, some of whom were also staff writers on the show.

• Albert Brooks, who was based in Los Angeles, contributed six films during season 1.

• Gary Weis, who specialized in comedy shorts and documentary pieces, many of which focused on New York City and some of its more eccentric inhabitants, helmed over forty shorts that aired during seasons 1–5.

• Tom Schiller, a member of the show’s original writing staff, directed shorts for seasons 3–5 and 14–18 under the segment title “Schiller’s Reel” (plus the occasional film during other seasons). Schiller’s oeuvre includes some of SNL’s funniest and artiest films, including mockumentaries that incorporate archival footage, and parodies and pastiches of European art and Hollywood genre films.

• Walter Williams directed over twenty episodes of The Mr. Bill Show, which aired during seasons 1–5.

• Adam McKay, who was a head writer on SNL for three of six of his seasons on SNL (21–26), pioneered the digital short on SNL and contributed to Robert Smigel’s “Saturday TV Funhouse” after his departure. McKay is cofounder, along with Will Ferrell, of funnyordie.com, one of the premiere sites for original comedy shorts on the web.

• T. Sean Shannon wrote and directed a series of bizarre (in a good way) digital shorts in season 30 entitled Bear City, which are set—you guessed it—in a city inhabited by bears (actually actors in bear costumes).

• Robert Smigel, a longtime staff writer on SNL, created a series of hilarious animated shorts presented under the segment title “Saturday TV Funhouse,” several of which were recurring: The Ambiguously Gay Duo, Fun with Real Audio, The X-Presidents, and The Anatominals. Smigel and his team are masters at imitating iconic animation styles, like the cartoons of Hanna-Barbera and Ruby-Spears, and the stop-motion animation of Rankin-Bass, makers of such holiday classics as Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964) and The Little Drummer Boy (1968).

• The Lonely Island, a comedy trio comprised of Akiva Schaffer, Jorma Taccone, and SNL cast member Andy Samberg, wrote, directed, and performed in over one hundred shorts under the segment title “An SNL Digital Short.” Many of their most memorable shorts featured original songs that showcased the musical talents of such stars as Adam Levine, Justin Timberlake, Michael Bolton, Lady Gaga, and Nicki Minaj. Schaffer and Taccone also directed other SNL shorts not presented under the “SNL Digital Short” banner, including episodes of MacGruber, which was adapted into a feature film in 2010 (see chapter 23).

The best of SNL’s film short library has been showcased on two specials. The first, SNL Film Festival, which aired on March 2, 1985, featured the best film shorts and commercial parodies since season 1. The special was hosted by Billy Crystal and featured reviews of the shorts by critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert. Twenty-four years later, on May 17, 2009, Andy Samberg hosted Saturday Night Live: Just Shorts, which was comprised of shorts from seasons 1–34.

Here, in chronological order, are some of SNL’s more memorable, entertaining, and provocative film shorts:

Homeward Bound, directed by Gary Weis (1.8)

SNL has never been much for sentiment, but considering it was the show’s first holiday episode, they were willing to let their guard down—if only for a few minutes. Set to the classic Simon & Garfunkel tune “Homeward Bound,” Weis’s film is a slow-motion montage consisting of a series of emotional reunions in an airport between recent arrivals and their friends and family waiting for them at the gate.

A Home Movie, directed by Howard Grunwald (1.13)

In addition to films by Albert Brooks, Gary Weis, and Tom Schiller, SNL also invited amateur filmmakers to send in their Super 8 and 16mm shorts. Selected films were screened in a segment entitled “Home Movies.” The filmmakers did not receive any monetary compensation—only the satisfaction of knowing their work would air on national television and be seen by millions of people. A viewer named Howard Grunwald submitted this forty-five second comedy short, which, according to the opening titles, he produced, conceived, and shot with some assistance from a pair of technical advisors. The opening credits of A Home Movie are twice as long as the film itself, which consists of a single, sixteen-second shot of the outside of a house (presumably Grunwald’s home). The End.

The Mr. Bill Show (1.15)

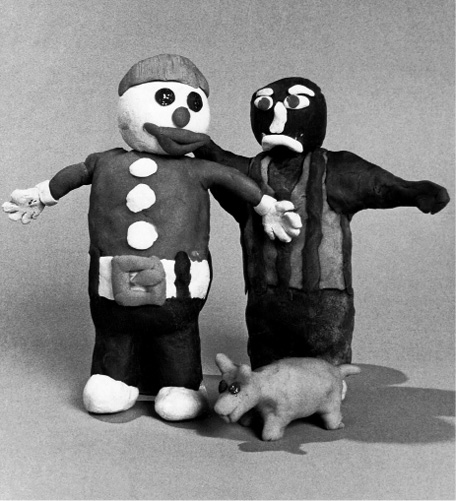

Oh nooooooooooo!

In the first episode of this parody of a children’s show, we are introduced to three clay figures: a little guy named Mr. Bill; his dog, Spot; and Mr. Bill’s nemesis, the evil Mr. Sluggo. The narrator is Mr. Hands (a pair of human hands), who doesn’t think twice about putting poor Mr. Bill in harm’s way. Over the course of three and a half minutes, Mr. Bill is stabbed by Mr. Sluggo, who, now pretending to be a doctor, amputates his leg. Mr. Hands next suggests Mr. Bill go on a “deep sea mission” and drops him in a pot of water. Then it’s time for Mr. Hands to brush Mr. Bill’s teeth, but the human size toothbrush wipes off his entire face. Finally, it’s time to skydive, but Mr. Bill’s parachute doesn’t work. Oh nooooooooo!

Mr. Bill was originally submitted by Walter Williams for the “Home Movie” segment. It’s purposely crudely made (the clay figures don’t actually move), completely original, and very unexpected, which is why it was followed by twenty more adventures in which Mr. Bill goes to the circus (3.15), to New York (4.2), fishing (4.6), to the movies (4.19), and to Los Angeles (7.3)—and runs into Mr. Sluggo every time.

“Oh noooooooooo!”: Mr. Bill and his dog Spot pose with his nemesis, Mr. Sluggo.

Mr. Bill’s creator ran into another kind of trouble when Williams was slapped with a lawsuit by the original Mr. Hands, Vance DeGeneres (Ellen’s brother), claiming he was entitled to artistic credit and 50 percent of all profits. “I want to be able to put Mr. Bill on my resume,” DeGeneres told the New York Times in 1979. In the same article, Williams confirmed that “definitely and obviously, I feel myself the sole creator.”

In 1980, DeGeneres told People magazine that when he and Williams lived together, they were working on an 8mm film for a comedy act. “We were sitting around the table one night and I started making a head out of Play-Doh and Walter started making a body for the head,” Williams explained. “Then we put it together and were just playing around—and somehow we started mutilating it. Then it hit us: If we did this right, it might make a film.” They moved to New York together, but their friendship ended over creative differences. In the same interview, DeGeneres said that he phoned Williams to give him a chance to settle the suit, but his former friend and roommate refused.

In November 1981, the Sarasota Journal reported that a New Orleans judge awarded Williams total control over the characters of Mr. Bill, Spot, Sluggo, and Mr. Hands and declared that Williams was responsible for “the basic idea in concept,” yet DeGeneres “participated in bringing that idea.” According to the judgment, Williams had to refile copyrights on all four characters and add DeGeneres’s name as cocreator. DeGeneres would also receive 25 percent of all net proceeds produced around the four characters. In exchange, DeGeneres relinquished all claims to copyright and trademark. David Derickson, who replaced DeGeneres as Mr. Hands, also joined the suit and was granted 5 percent of the proceeds from Mr. Bill records and books on the market and 20 percent of the past, present, and future revenues derived from the eleven shorts he coproduced with Williams.

“Crackerbox Palace” and “This Song” (2.8)

In the 1970s, music videos became a popular form of entertainment on television in both Australia (on shows like Countdown [1974–1987] and Sounds Unlimited/Sounds [1974–1987]) and the United Kingdom on the long-running Top of the Pops (1964–2006). Prior to the debut of MTV in 1981 and the USA Cable Network show Night Flight (1981–1996), music videos on American television were a rarity.

On November 20, 1977, Saturday Night Live debuted two music videos by George Harrison: “Crackerbox Palace” and “This Song,” both directed by Harrison’s close friend, Monty Python’s Eric Idle.

In his memoir, I, Me, Mine, Harrison recalled how the song “Crackerbox Palace” was inspired by the name a comedian named Lord Buckley gave his “beaten-up house in Los Angeles.” Harrison thought the name “sounds like a song” and wrote it down on a cigarette pack. The result is a playful little ditty sung by Harrison in the video as he welcomes us to Crackerbox Palace, which is home to an odd assortment of inhabitants, who look like they wandered over from a Monty Python sketch—gnomes in raincoats, British military officers, women clad in leather, clowns, drag queens, and a dummy of the Queen. The video was shot in Harrison’s home, Friar Park, a 120-room Victorian neo-Gothic mansion in Henley-on-Thames in South Oxfordshire that he purchased in 1970. In 1999, a thirty-three-year-old Liverpool man, who according to a New York Times story was mentally ill and obsessed with the Beatles, broke into Friar Park and stabbed Harrison in the chest, puncturing his lung.

Harrison’s “This Song” is a self-referential tune from his 1976 album Thirty Three & 1/3. It was written after he spent a week in a New York courtroom defending himself and his 1970 hit song “My Sweet Lord” against accusations of plagiarism. A suit was filed against Harrison claiming he plagiarized the song “He’s So Fine,” written by Ronald Mack and recorded by the Chiffons in 1963. In I, Me, Mine, Harrison describes “This Song” as “a bit of light comedy relief—and a way to exorcize the paranoia about song writing that had started to build up in me. I still don’t understand how the courts aren’t filled with similar cases—as 99 percent of the popular music that can be heard is reminiscent of something or other.” “This Song” opens with a policewoman dragging Harrison into a courtroom, where he testifies that the very song that he is singing doesn’t infringe on any copyright and has no point (I won’t quote any lyrics for fear of infringing on Harrison’s copyright. You can watch for yourself on YouTube). As for Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music, Harrison was found guilty of subconsciously plagiarizing “He’s So Fine” and was ordered to pay damages.

Harrison’s connection to Eric Idle didn’t end here. When Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) lost one of its financial backers right before it was going into production, Harrison and his business partner Denis O’Brien agreed to invest in the film. They formed HandMade Films, which continued to produce and distribute films throughout the 1980s, including Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981) and Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1982), and several British art house films, including Mona Lisa (1986), Withnail and I (1987), and The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (1987).

Three Films by Tom Schiller

Don’t Look Back in Anger (3.13)

Writer/director Tom Schiller produced a pair of shorts, airing a few weeks apart in 1978, that were self-referential films about two of SNL’s most popular cast members, John Belushi and Gilda Radner, whose careers tragically ended far too soon.

In Don’t Look Back in Anger, John Belushi, who is now an elderly, white-haired old man who walks with a cane, takes us on a tour through a snowy graveyard, which he says is the Not Ready for Prime Time Cemetery, where all of his castmates are buried. “I was one of those ‘Live Fast, Die Young, Leave a Good-Looking Corpse’ types,” he confesses, “but I guess they were wrong.” He tells us they all died young; Bill Murray, who lived the longest, was thirty-eight. He points out each of their graves and share a little about what they did after the show (Gilda had her own show in Canada, Laraine had a pecan farm in the San Fernando Valley) and how some of them died (Jane Curtin from complications during cosmetic surgery, Garrett Morris of a heroin overdose, and Dan Aykroyd in a motorcycle crash).

“Why me, why did I live so long?” he asks. “They’re all dead. I’ll tell you why. Because I’m a dancer.” He begins to dance to the Yiddish song “Roumania, Roumania,” by Aaron Lebedeff. Ironically, Belushi would be the first to go. He died of a drug overdose on March 5, 1982, and was laid to rest on Martha’s Vineyard on March 11, 1982, exactly four years after the film first aired on SNL.

Schiller’s decision to shoot in black and white adds to the film’s haunting quality. As Michael Streeter observes in Nothing Lasts Forever: The Films of Tom Schiller, the film is about the future, yet it has the look and feel of the past: “The manner in which Schiller manipulates time. The manner in which it is shot, the film scratches, Belushi’s old-fashioned mustache and garb, the fact that he travels by train—all make this film that is set in the future look as if it were produced in the thirties and forties.”

In Judith Belushi Pisano and Tanner Colby’s Belushi: A Biography, Schiller explained that the title was a combination of the 1967 Bob Dylan documentary Don’t Look Back and the 1956 British “angry young man” drama Look Back in Anger by John Osborne, which was adapted into a film in 1958 starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom. Pisano told Streeter that she had considered using the title for her own heartfelt 1990 autobiography about coping with her loss, but she instead decided to go with Samurai Widow.

La Dolce Gilda (3.17)

One of Schiller’s talents as a filmmaker is his ability to pastiche cinematic styles of the past. He succeeds once again in La Dolce Gilda, a homage to famed Italian director Federico Fellini and two of his cinematic masterpieces: La Dolce Vita (1960), starring Marcello Mastroianni as a journalist who has an identity crisis while covering the jet set in Rome; and 8½ (1963), in which Mastroianni plays an Italian director who struggles to reconcile his past with the present and his fantasies with reality as he prepares for his next film. In La Dolce Gilda, Gilda is struggling with her newfound fame. She arrives at a party with an unnamed woman who bears a slight resemblance to Italian film director Lina Wertmüller (Laraine Newman) and “Marcello” (Dan Aykroyd), who, like Mastroianni in the orgy sequence in La Dolce Vita, climbs onto a woman’s back and begins to ride her. Once inside, she is overwhelmed by the attention (even her mother is there, telling her to eat something) and leaves the party. Outside, she walks along a dock as the sun comes out. Accordion music, from Nino Rota’s score for Fellini’s Amarcord, plays in the background. She turns and, addressing the camera, tells us to leave her alone. She walks away, but turns around and tells us to come closer. “You know I love you, my little monkeys,” she says, “but leave me my dreams. Dreams are like paper, they tear so easily. I love to play. Every time I play . . . you win. Ciao.” As Gilda walks away, the camera pans to a mime holding a balloon. He opens his jacket to reveal a paper heart on his chest. He releases the balloon.

Schiller’s visual design, black-and-white cinematography, and frenetic editing and camerawork, complete with close-ups of mouths speaking what is obviously postdubbed English, brilliantly capture the milieu of a Fellini movie. The Italian director himself agreed. Schiller had the opportunity to meet Fellini and show him the film while he was vacationing in Rome. According to Streeter, Fellini was amused by La Dolce Gilda. The director told Schiller it was carina (“pretty” or “sweet”) and “had the atmosphere of some of his films.”

Java Junkie (5.8)

One of Schiller’s most original films is this pastiche of a 1940s film noir, specifically The Lost Weekend, a 1945 drama starring Ray Milland as an alcoholic that won four Oscars including Best Picture, Actor (Milland), Direction (Billy Wilder), and Screenplay (Wilder and cowriter, Charles Brackett). In Java Junkie, Peter Aykroyd plays a guy named Joe who is feeling low after losing his job and his girl, Betty. Every morning he orders breakfast at the same diner, only on this one particular morning he decides to skip breakfast and just have a cup of coffee. But one cup isn’t enough, and Joe keeps drinking and drinking until he becomes a “java junkie.” He starts wandering the streets looking for that next cup and is picked up by the police. After seven weeks of rehab in “Maxwell House,” where he’s treated for caffeine addiction, he is ready to resume his life with that “java monkey” off his back.

A Day in the Life of a Hostage (6.9)

The Iranian hostage crisis, which started on November 4, 1979, with the storming of the United States Embassy in Tehran, lasted one year, two months, two weeks, and two days, until the fifty-two remaining American hostages were released by Iran to U.S. custody on January 20, 1981. All during that time, the hostage crisis, including the failed negotiations for their release and the failed rescue attempts, were front-page news. CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite ended his broadcast by stating the number of days the hostages had been held in captivity. Backlash against Iranians living in the United States was on the rise as many Americans, in a display of national solidarity and support for the hostages, tied yellow ribbons around trees in their front yards. The yellow ribbon, a cultural symbol for remembrance, was popularized by the 1973 song “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” the top-selling single in the United States recorded by Tony Orlando and Dawn.

The song is heard over the radio in the beginning of this haunting film shot entirely from the point of view of one of the hostages, David Posner, who is trying to resume a normal life—but he is bombarded by people who recognize him (a crowd in a piano bar start singing “Tie a Yellow Ribbon” to him) or want him to sell them his story or endorse their cologne. At the end, he is welcomed back by Uncle Sam himself, who strangles him with a yellow ribbon. It is a haunting image—and quite a radical statement for a network television show.

The same episode featured three other segments devoted to the Iranian hostage crisis. In The Rocket Report, Charles Rocket is at the ticker-tape parade held in New York City on January 30, 1981, where he sees one of the hostages, Barry Rosen. The mental cruelty of the Iranian militants toward the American hostages (all of which was made public after their release) was the target of a commercial parody in which a hostage is about to be executed, only to find out it’s a joke—one of many, according to pitchman Charles Rocket, that can be found in the Iranian Joke Book. A third sketch is a meeting of the Iranian Student Council, at Tehran University, who are jubilant over their successful year (they raised over $8 billion thanks to the hostage crisis). They try to figure out what they will do next year. The audience is quiet, probably thinking that maybe all this Iranian humor is, as they say, “too soon.”

Andy Warhol’s TV, by Don Munroe, Vincent Fremont, Sue Etkin (7.1, 7.2, 7.4)

The King of Pop Art appeared on SNL in three video shorts in the early 1980s (7.1, 7.2, 7.4), and like his underground films of the 1960s, they are plotless and all talk about subjects like makeup, death, and stardom (“Death means a lot of money, honey. Death can really make you look like a star. But then it can be all wrong because if your makeup isn’t right when you’re dead then you won’t look really right.”). Warhol was certainly right about the money part. Twenty-one years after his death, Warhol’s “Eight Elvises” painting sold to a private collector for $100 million.

The most entertaining was the first video in the series, in which Warhol candidly gives his opinion about SNL: “In the first place, I never thought I’d ever be on Saturday Night Live because I hate the show. I never watched it. I don’t think it was great and if you’re home on Saturday night, why ARE you home on a Saturday night and I think all the comedians should be beautiful and not funny.” It’s hard to take anything Warhol ever said publicly very seriously, yet in his diaries, published two years after his death in 1987, he expressed how surprised he was that people watched SNL: “So many people must see Saturday Night Live, because instead of people on the street saying, ‘There’s Andy Warhol the artist,’ I heard, ‘There’s Andy Warhol from Saturday Night Live.’ They’d seen my first segment on it the night before.” Two days later he wrote: “So many people keep saying they saw me on Saturday Night Live. I guess people do stay in. I don’t know. I’m surprised.” Warhol’s venture into television continued with his cable series Andy Warhol’s TV, which was shown on Manhattan Cable in 1983–1984, followed by Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes (1985–1987) on MTV.

In addition to the shorts featuring Warhol, season 7 attempted to raise the show’s hip factor by featuring a music video, “Goodbye Sadness,” directed by Yoko Ono. The song appears on Season of Glass, Ono’s solo album released six months after the fatal shooting of John Lennon. The video includes footage of both Ono and Lennon. There was also a short by artist William Wegman (7.6), who made his SNL debut back in 1976 (1.15) when he and his Weimaraner, Man Ray, appeared in the first of several shorts by Gary Weis (1.16, 2.5).

Synchronized Swimming, directed by Claude Kerven (10.1)

Season 10 got off to a great start with the addition of some stellar new cast members (Martin Short, Christopher Guest, and Billy Crystal), characters (Ed Grimley, Fernando), and this hilarious short profiling Gerald (Harry Shearer) and Lawrence (Martin Short), two brothers with a dream—to win a gold medal in synchronized swimming in the 1992 Olympics (they will need the extra time to practice because as Lawrence admits, “I’m not that strong a swimmer.”).

Christopher Guest plays their fey director, who was most likely the inspiration for Corky St. Clair, the theater director Guest played in his 1996 mockumentary Waiting for Guffman. The short was directed by Claude Kerven, who had directed other segments for SNL and several ABC Afterschool Specials, including High School Narc (1985).

White Like Me, directed by Andy Breckman (10.9)

The inspiration for one of the best SNL shorts of the 1980s was Black Like Me, white author John Howard Griffin’s 1961 autobiographical account of the racism he experienced traveling as a black man for six weeks through the segregated South on a Greyhound bus. The tables are turned in this version in which Eddie Murphy, with the help of makeup artists, decides to go underground and experience America as a white man. The results of his experiment are hilarious. As “Mr. White,” he discovers that white people don’t have to pay for anything (as long as there are no black people around), the New York City bus turns into a party, and banks will loan you all the money you want (with no obligation to pay it back). “So, what did I learn from all of this?” Murphy asks. “Well, I learned that we still have a very long way to go in this country before all men are truly equal. But I’ll tell you something. I’ve got a lot of friends and we’ve got a lot of makeup.”

The short was directed by Andy Breckman, who wrote for SNL in the mid-1980s and later created the long-running detective series Monk (2002–2009).

The Narrator That Ruined Christmas (27.9)

In this parody of Rankin and Bass’s annual television special Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), the snowman who serves as the narrator begins the story—then stops suddenly during his introduction. In the post-9/11 world, it just seems so trivial. So he invites the two confused children watching to meet him down at Ground Zero for a reality check. Fortunately, Santa comes by to set the narrator straight, explaining that now is exactly the time that he should be bringing happiness to children. He also chastises the narrator for being one of those “show business types” that shifts the focus away from the crisis onto himself. The narrator sees the light, only to be interrupted by Tom Brokaw with a special NBC News report that the FBI has placed the nation on a forty-five-minute alert.

For anyone who grew up watching Rudolph every year, it’s amazing how Robert Smigel, who cowrote the script with Louis C.K., Michael Gordon, and Stephen Colbert, and his collaborators are able to capture the look of the original puppets with such precision.

“Christmas Time for the Jews” (31.9)

Robert Smigel uncovers the mystery of what Jews do at Christmas time in this music video directed by David Brooks. Shot in black and white using stop-motion claymation, the title song is sung by Darlene Love, who also appears in the video in claymation form (when it first aired on the 2005 Christmas show, Love was also live in the studio singing “White Christmas”). On Christmas Eve—the night the Jews take over the town—they go to the movies, eat Chinese food, crank up Barbra Streisand, have bar fights, and see Fiddler on the Roof with Jewish actors. The song, written by Smigel, Scott Jacobson, Eric Drysdale, and Julie Klausner, should be added to everyone’s holiday playlist. Since 1986, Love has made an annual appearance around the holidays on David Letterman’s late-night shows to sing “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home),” which was first recorded in 1963 by Love for Phil Spector’s legendary Christmas album, A Christmas Gift for You from Philles Records.

“Lazy Sunday” (31.9)

The second “SNL Digital Short,” which aired on the same holiday episode as “Christmas Time for the Jews,” is a rap music video entitled “Lazy Sunday.” The song is performed by Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell in true rap style with plenty of attitude as they shout and gesture into the camera. The joke is what they are rapping about—going to the Magnolia Baker for cupcakes, getting directions on Mapquest, buying snacks to bring into the movie theater, and going to see the film Chronicles of Narnia (2005). Within twenty-four hours after it first aired, the video, which was made with Samberg’s collaborators, Lonely Islanders Schaffer and Taccone, became a viral hit, and the song was soon reportedly being played on the radio and in bars. In a New York Times article on the video’s popularity, David Itzkoff reported that approximately a week after it aired, it was downloaded 1.2 million times from YouTube and was popular on both nbc.com and iTunes. The video was not only a turning point in the careers of Samberg and his collaborators, but it broadened the appeal of SNL, which is regarded by millennials as their parents’ comedy show. “Lazy Sunday” may have aired on a national television show on a major network, but it has the look and feel of a YouTube video, along with the same ironic playfulness that permeates contemporary youth culture, particularly comedy shows like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (1996–present) and The Colbert Report (2005–present).

Journey to the Disney Vault (31.16)

Robert Smigel’s “TV Funhouse” uncovers some of Walt Disney’s dirty little secrets in this classic commercial parody. When Disney rereleases one of their classic animated films on DVD, we are encouraged to go out and buy our copy now because it’s only available for a limited time. After a certain date, the film will go back into to the “Disney vault,” a magical underground storage unit. This parody of an ad for Walt Disney Home Entertainment starts off with a warning that some of Disney’s recent releases, with titles like Bambi II, Cinderella II, Bambi 2002, Hunchback 6: Air Dog Quasi, and Jungle Book 3.0, will soon be going back into the Disney vault for ten years. When a boy and girl are watching it on television, they wish they could go into the Disney vault. Mickey Mouse appears and grants their wish. They go on a magical journey to the Disney vault, where they learn the truth about Uncle Walt—how he was a friendly House Un-American Activities Committee witness, was planning a Civil War theme park, and had his own personal copy of Song of the South (1946) that he played only at parties.

“Dick in a Box” (32.9)

“Dick in a Box”: Two guys (Andy Samberg, left, and Justin Timberlake) sing about the surprise they will be giving their special ladies this Christmas (32.9).

NBC/Photofest © NBC

The Lonely Island scored again with another music video that aired on the holiday show in 2006, and like “Lazy Sunday” it became a viral hit. This R&B ballad is sung by Andy Samberg and Justin Timberlake, who collaborated with Akiva Schaffer, Jorma Taccone, Asa Taccone, and Katreese Barnes, all of whom won a Creative Arts Emmy for Outstanding Original Music and Lyrics. Both men are singing to their respective girlfriends (Kristen Wiig, Maya Rudolph), about the very special package they have for them this Christmas—their package, which they’ve inserted in a hole in a gift-wrapped box. The word “dick” is bleeped out sixteen times, but NBC did agree to post it uncensored on their website.

“Iran So Far” (33.1)

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, former president of Iran, made some outrageous statements while he was in office in 2005–2013. He called the Holocaust a “myth,” accused America of creating HIV to loot African nations, said Israel should be “wiped off the map,” the “mysterious September 11 incident” was a pretext for wars against Afghanistan and Iraq (the U.S. delegation at the United Nations walked out the door when they heard that one), and in Iran, there are no gay people. The latter statement was the inspiration for this inspired music video in which Andy Samberg sings a love song to Mahmoud (played by Fred Armisen) with vocals by Maroon 5’s Adam Levine. It was the perfect response to the rantings of a lunatic.

Japanese Office (33.12)

Ricky Gervais, co-creator (with Stephen Merchant) and star of the original British version of The Office (2001–2003), introduces a clip from the Japanese show that he used as the jumping-off part. Shot in documentary style, it all looks very familiar as we meet the characters who bear a close resemblance to their American counterparts, except they speak in faux Japanese and bow to each other: Steve Carell as “the boss,” Jason Sudeikis as the “Jim” character, Kristen Wiig as “Pam,” Bill Hader as “Dwight,” and Kenan Thompson as “Stanley.”

The idea of a Japanese version of The Office is not so far-fetched, considering versions of the show were produced in France (Le Bureau [2006]), Germany (Stromberg [five seasons aired between 2004 and 2012 with feature film in the works]), Quebec (La Job [2006–2007]), Chile (La Ofis [2008]), Israel (HaMisrad [2010–2013]), and Sweden (Kontoret [2012–2013]).

“3-Way (The Golden Rule)” (36.22)

The boys are back. The “Dick-in-a-Box” guys (Andy Samberg and Justin Timberlake) are surprised to find each other at the same girl’s door ready for a hookup. But that’s okay because she (Lady Gaga) wanted them both. And that’s okay, for as the boys explain, according to “the Golden Rule” a three-way is okay (and not gay) as long as there is a “honey” in the middle.