The Trial Before Pilate (15:1–20)

Very early in the morning (15:1). The working day of a Roman official began at the earliest hour of daylight. Seneca attests that Roman trials could begin at daybreak.357 Pliny completed his work by 10:00 A.M.; Vespasian finished before dawn.358 If the council spent the early hours of daylight examining Jesus, they may have been too late for Pilate’s tribunal.

COINS MINTED UNDER PONTIUS PILATE

They bound Jesus, led him away and handed him over to Pilate (15:1). Pilate’s official title was prefect (see inscription found in Caesarea identifying him as Praefectus Iudaeae). The governors were called procurators only after A.D. 44. As governor, Pilate had the power of life and death over all the inhabitants of his province.359 He was of equestrian rank (knight, wealthy enough to own a horse). In this rank, he would have had no assistants of a similar status and no team of Roman officials to handle all of the administrative matters. A large part of the everyday chores of government and administration was thus carried out by the local councils and magistrates. They had the power to arrest, take evidence, and make a preliminary examination in order to present a case before a governor for a formal trial. The Roman authorities held them accountable for outbreaks of violence and would replace them. The governor, however, was ultimately responsible for ensuring that order was maintained and for deciding the death penalty.

The chief priests accused him of many things (15:3). No criminal code existed for the non-Roman citizen tried in the provinces. It was technically known as a “trial outside the system.” The governor was free to make his own rules and judgments as he saw fit, to accept or reject charges, and within reason to fashion whatever penalties he chose. Governors, however, tended to follow the legal custom with which they were familiar.

Trials normally took place in a public setting before the governor, who sat on his tribunal. Since there were no public prosecutors, a prosecution’s case was brought by private third parties, who presented formal charges (cf. the trials of Paul, Acts 24:1–9; 25:1–27).

The Roman governor would not have put anyone on trial for his life simply for transgressing Jewish religious regulations. When Paul was arrested, the Roman garrison commander wrote to the governor Felix in Caesarea, “I found that the accusation had to do with questions about their law, but there was no charge against him that deserved death or imprisonment” (Acts 23:29; see the reaction of Gallio in 18:14–17). The Sanhedrin may have found Jesus guilty of blasphemy and deserving of death, but a religious charge would not suffice for Pilate to take action. The governor only cared that matters religious did not become matters political. The chief priests must thus formulate a charge that will capture his attention and carry a death sentence. The charges need to be political, which explains why Pilate asks Jesus, “Are you the king of the Jews?” (Mark 15:2). Charges of maiestas, “the diminution of the majesty of the Roman people,” were increasingly frequent under Tiberius.360

Josephus bemoaned the various would-be kings who rose up and caused disturbances:

And so Judaea was filled with brigandage. Anyone might make himself king as the head of a band of rebels whom he fell in with, and then would press on to the destruction of the community, causing trouble to few Romans and then only to a small degree but bringing the greatest slaughter upon their own people.361

Now it was the custom at the Feast to release a prisoner whom the people requested (15:6). This tradition may derive from the days of the Hasmonean kings, and the Romans may have continued it when it suited their purposes. A papyrus from A.D. 85 contains a report of judicial proceedings before the prefect of Egypt and quotes the words from the governor to the prisoner: “You were worthy of scourging … but I will give you to the people.”362 A text from the Mishnah rules, “They may slaughter (the Passover lamb) … for one whom they (the authorities) have promised to release from prison.”363

A man called Barabbas (15:7). The name Barabbas means “son of Abba.” This name distinguishes him from others with the same personal name.

The crowd came up and asked Pilate to do for them what he usually did (15:8). Governors were known to enter into conversation with the crowd, although a first-century papyrus warns against this since it may lead to injustice. The crowd is probably composed of partisans supporting the priestly hierarchy. It would be easy to stir them up if they were led to believe that Jesus has somehow threatened the temple. The temple was not only a potent religious symbol, it provided employment to a large segment of the population of Jerusalem.

The Mocking and Crucifixion of Jesus (15:15–46)

He had Jesus flogged, and handed him over to be crucified (15:15). Scourging was a customary preliminary to crucifixion. The prisoner was bound to a pillar or post and beaten with a flagellum. This whip consisted of leather thongs plaited with pieces of bone, lead, or bronze or with hooks and was appropriately called a scorpion. Gladiators sometimes fought with them. There was no prescribed number of lashes so that in some cases the scourging itself was fatal. The balls would cause deep contusions as the flesh was literally ripped into bloody ribbons. It was so horrible that Suetonius claimed even Domitian was horrified by it.364 Significant blood loss could also occur, critically weakening the victim.

The soldiers led Jesus away into the palace (that is, the Praetorium) (15:16). During his sojourns to Jerusalem, Pilate probably stayed in the luxurious palace of Herod the Great (near the Tower of David and the Jaffa Gate), the highest point in the city. Philo recalls that when Pilate was first appointed governor he stayed in Herod’s palace.365 Others argue that he resided in the Antonia Fortress (named after Mark Anthony) adjacent to the northwest corner of the temple; it served as the barracks for the Roman cohort. It seems more likely that the governor would choose to lodge in Herod’s more opulent palace.

SOLDIER GAMES

A Roman era pavement inscribed with lines related to “the king’s game.”

They put a purple robe on him (15:17). The mocking of Jesus by the soldiers is intended to parody the charge that he is king of the Jews. The purple cloak probably refers to the oblong-shaped garment fastened around the neck by a brooch that was a foot soldier’s equipment (chlamys), or perhaps the cloak of the lictor. According to Suetonius, Caligula wore one.366 It is intended to be a mock royal robe.367

TREE USED FOR MAKING CROWN OF THORNS

They twisted together a crown of thorns and set it on him (15:17). This crown may or may not be an instrument of torture. The soldiers are improvising and grab whatever is at hand. Thus the thorns may come from a type of palm tree common to Jerusalem, a dwarf date palm or thorn palm, which grew as an ornamental and had formidable spikes. The leaves could be easily woven and the long spikes from the date palm inserted to resemble a radiate crown.368 Evidence for this type of crown is found in seals excavated from the Roman camp in Jerusalem. Or, the soldiers may have simply grabbed a clump of thorns and put them on his head like a cap.

Hail, king of the Jews! (15:18). The homage of the soldiers parodies that given to the emperor, “Ave Caesar, victor, imperator.” Philo records similar mockery of an imbecile named Carabas in Alexandria. He was used as a stand-in to lampoon Herod Agrippa I when he was proclaimed king of Judea.369

A certain man from Cyrene, Simon, the father of Alexander and Rufus (15:21). The names are Greek and Latin, although Simon may reflect the Hebrew Simeon. If Simon is a Jew, which seems likely, he may have been a member of the synagogue of Cyrenians that later opposed Stephen (Acts 6:9). Apparently, Rufus and Alexander are known to the first readers of this Gospel. A Rufus is mentioned in Romans 16:13 and in Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians 9:1. An ossuary with the name “Alexander, son of Simon” has been discovered in Jerusalem.370

They forced him to carry the cross (15:21). Normally, a condemned person carried the crossbeam (patibulum) to the crucifixion site, where a vertical post (stipes, staticulum) had already been fixed in the ground. Wood was scarce, and crosses were probably used more than once. Plutarch says that “every criminal who goest to execution must carry his own cross on his back.”371

Mark does not tell us why Jesus is unable to carry his own cross. We can surmise that he was too weak or too slow after the ordeal of his scourging, which also may explain his quick death (15:44). Cicero mentions an executioner’s hook used to drag the condemned to the place of execution.372 “Compel” is a technical term for commandeering a person or his property (see Matt. 5:41). Simon is grabbed from the crowd and forced to carry the crossbeam to the place where Jesus will be crucified.

They brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha (which means The Place of the Skull) (15:22). According to Roman law (and Jewish, Lev. 24:14), crucifixion was to take place outside the city. Quintilian commended crucifixion as a deterrent and noted that the executioners chose “the most crowded roads where the most people can see and be moved by this fear.”373 Josephus reports that during the siege of Jerusalem, the Romans crucified five hundred or more victims every day opposite the wall, nailing their victims in different postures as a spectacle for those in the city.374 The crucifixion site would be near roads leading into the city where people could learn what happens to malefactors and would-be kings.

Jesus is taken to a place called Golgotha, which Mark interprets for his Greek-speaking readers as “skull place.” The more familiar term Calvary derives from the Latin translation calvaria, which means “skull”. The name Golgotha does not appear in any other extant source from antiquity other than the Gospels. The name may refer to (1) the shape of the outcropping of rock that resembled a skull, (2) the place where executions were carried out, or (3) a region that included the place of execution and a cultivated tract of land where there were tombs.375 This last option seems best. Taylor concludes:

Golgotha was probably an oval-shaped abandoned quarry located west of the second wall, north of the first wall. Jesus may have been crucified in the southern part of this area, just outside the Gennath Gate, and near the road going west, but at a site visible also from the road north and buried some 200 m. away to the north, in a quieter part of Golgotha where there were tombs and gardens.376

This site is not far from the Gennath (Gardens) Gate mentioned by Josephus; it was located in the first wall and fits John’s mention of a garden in the place (John 19:41).377 Exposed rock in this area shows evidence of ancient quarrying, and it may have been a rejected portion of an ancient preexilic white stone quarry. One scholar suggests that the early Christians knew that Golgotha was a rejected quarry stone, which brings to mind Psalm 118:22, mentioned in Mark 12:10 (see also Acts 4:11 and 1 Peter 2:7).378

Constantine drew on local tradition to build “a great sacred enclave” in this area in 325–35.379 The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is currently located on this site. Despite this ancient tradition, several questions remain. Was it outside the city wall in the first century? Was it not too close to the temple (and the palace of Herod)? Since the prevailing winds came from the west, nearly all extant tombs are found to the north, east, and south of Jerusalem. Did the Gennath Gate open onto a roadway?

Then they offered him wine mixed with myrrh (15:23). According to a Talmudic tradition, the women of Jerusalem offered a narcotic drink to people condemned to death in order to alleviate the pain of execution, but it refers to wine and frankincense (see Prov. 31:6–7).380 The text, however, implies that the executioners, not pious women, offer the drink. Pliny regarded the finest wine as that “spiced with the scent of myrrh.”381 The Romans did not consider it to be intoxicating but more of a woman’s drink.382 The executioners may have given this drink to exhausted prisoners on the way to the place of execution to give them more strength so that they would last longer and suffer longer.

Another possibility is that this gesture continues the mocking of Jesus as a triumphant king. At the end of a Roman triumphant procession, the triumphator is offered a cup of ceremonial wine that he refuses to drink but pours out on the altar at the moment of sacrifice.383

Jesus rejects the offer of wine because he has made a vow of abstinence at the Last Supper (14:25) and wishes to remain fully conscious to the bitter end. He will drink the Father’s cup instead (14:36).

They crucified him (15:24). Mark does not need to describe crucifixion to his readers since they would be familiar with it. The victim is stripped to increase the humiliation and fastened to the crossbeam with nails and/or ropes. The executioners lift up the crossbeam with forked poles until the victim’s feet clear the ground and then attach it to the stake. Most guess that “Jesus’ cross stood some 7 ft. high.”384 Since the nails do not support the whole body, a plank (sedile, sedecula) is fastened to the stipes to support the buttocks, which explains Seneca’s mention of “sitting on a cross.”385

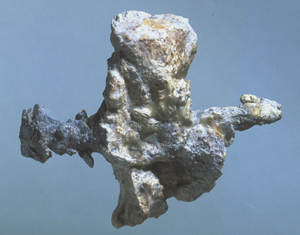

CRUCIFIED BONE

The heel bone of a man crucified with an iron nail that pierced the bone and fastened him to the wood. The bone was found in an ossuary (burial box) in a Jerusalem tomb.

The only extant bones of a crucified man were discovered in Jerusalem in 1968 at Giv‘at ha-Mivtar in a group of cave tombs dating from the second century B.C. to A.D. 70. A man named Jehohanan had been crucified sometime between A.D. 7 and 66.386 Initial analysis suggested several possibilities that have later been refuted. (1) A scratch on the forearm near the wrist was interpreted to mean that he was nailed to the cross beam through the forearms. Thus it is possible that Jesus was not nailed to the cross through his palms, as Christian art has normally depicted it, but through the wrists or arms. The word translated “hands” in Luke 24:39–40 and John 20:20, 25, 27 may refer to wrist or arm.387 Later analysis, however, has revealed that Jehohanan’s arms and hands had not undergone violent injury, and it is more likely that he had been tied to the crossbeam with ropes.

Zugibe has determined that the upper part of the palm of the hand can support the weight of the body nailed to a cross.388 It is therefore possible that tradition is correct, and Jesus was nailed to the cross through the palms of his hands.

(2) The iron nail piercing the man’s heel bone had apparently hit a knot when it was driven into the cross and was bent, making it difficult to extract from the bone. The initial report suggested that this nail had been driven through both heels and that the man’s legs were either pressed together and twisted so that the calves were parallel to the cross beam or possibly were spread apart. Later analysis showed that the nail was shorter than first described and was driven through the right heel, suggesting that the man had straddled the upright beam with each foot nailed laterally to the beam. Executioners employed a variety of ways of crucifying victims, and we cannot know precisely how Jesus was affixed to the cross.

(3) It was initially reported that the man’s legs were fractured from a blow from a massive weapon shattering the right shin into slivers and fracturing the left one. This procedure was known as crurifragium and hastened death. According to the fictional Gospel of Peter 4:14, the people were angry with the penitent thief and did not allow his legs to be broken so that he would suffer longer. Later analysis of the bones, however, has questioned whether the man’s legs had been broken.

Death by crucifixion normally came slowly and tortuously. Horace records a jeer that reflects this protracted suffering, “You’ll hang on no cross to feed crows.”389 Seneca’s letters offer gruesome images of crucifixion:

Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain dying limb by limb, or letting out his life drop by drop, rather than expiring once for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree, long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly weals on shoulders and chest, and drawing the breath of life amid long drawn-out agony? He would have many excuses for dying even before mounting the cross.390

In another letter he writes:

Yonder I see instruments of torture, not indeed of a single kind, but differently contrived by different peoples; some hang their victims with head toward the ground, some impale their private parts, others stretch out their arms on fork-shaped gibbet; I see cords, I see scourges, and for each separate limb and each joint there is a separate engine of torture.391

Reading this, one better understands the meaning of the word “excruciating,” which derives from the Latin excruciatus, out of the cross.

Dividing up his clothes, they cast lots to see what each would get (15:24). Executioners customarily shared out the minor personal belongings of the condemned.392 Not only does the victim suffer from the excruciating pain and thirst as well as the torture of insects burrowing into open wounds, he must also endure the humiliation of exposure. It is likely that Jesus was left with a loin cloth out of deference to Jewish scruples about nakedness.

The written notice of the charge against him read: THE KING OF THE JEWS (15:26). Jesus, who resisted any political overtones to his messiahship, is executed as a political Messiah. A placard citing the basic charge against him is probably hung around his neck as he departs for the execution site. To the Romans, any claim to kingship was treasonous.

They crucified two robbers with him, one on his right and one on his left (15:27). The robbers may have been involved in the insurrection with Barabbas (15:7), or they may be common thieves or bandits (11:17; see 2 Cor. 11:26).

Those who passed by hurled insults at him (15:29). Mocking a victim was customary and stemmed from the mob mentality of kicking a man when he is down. A rabbinic story tells of the crucifixion of Jose ben Joezer and the scorn hurled at him by his wicked nephew Jakum. He came up riding a horse on the Sabbath and mocked him: “Behold my horse which my master lets me ride and thy horse which thy Master (God) makes thee sit.”393 The “Aha” appears as a derisive cry in the Psalms, and the wagging of heads is a gesture of contempt.394

At the sixth hour darkness came over the whole land until the ninth hour (15:33). The darkness would have evoked several different images for ancient readers. (1) It was a sign of mourning (Jer. 4:27–28). According to a Talmudic tradition, when the president of the council dies, the sun is darkened; the rabbis comment that the sun mourns for the man even if humans do not.395 (2) Darkness was associated in the ancient world with the death of great men. Philo saw the sun and moon as natural divinities and wrote that eclipses announce the death of kings and the destruction of cities.396 Vergil wrote: “The Sun will give you signs. Who dare say the Sun is false? Nay, he oft warns us that dark uprisings threaten, that treachery and hidden wars are upswelling. Nay, he had pity for Rome when, after Caesar sank from sight, he veiled his shining face in dusky gloom, and a godless age feared everlasting night.”397 (3) In the Scriptures, darkness is an apocalyptic sign of judgment and could be construed as signaling the advent of divine judgment.398 The darkness that descended during Jesus’ crucifixion turns upside down the expectation derived from Isaiah 60:2 that though darkness covers the earth and dark night the nations, God’s light will shine on Jerusalem. (4) The darkness also announces the great Day of the Lord in prophets such as Amos, and the darkness that settles on the land signifies that the day has dawned with a new beginning. (5) The darkness may veil the shame of the crucifixion: “God hides the Son from the blasphemer’s leering.”399

“Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?”—which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (15:34). Jesus does not form the words of the prayer himself as he did in Gethsemane (“Abba”); rather, he cites a proverbial expression of distress from Psalm 22:1. One could not expect a crucifixion victim to recite an entire psalm, but it is possible that citing the first verse of the psalm refers to the entire psalm. Without chapters and verses to identify specific passages, initial words or key phrases were cited (see Mark 12:26). If this is the case here, Jesus prays the opening words of this lament psalm that, when read through to the end, expresses not only bitter despair but also supreme confidence. This interpretation does not deny the real anguish that Jesus experiences but understands his cry as an expression of trust that God will intervene and ultimately vindicate him.

Listen, he’s calling Elijah (15:35). The final taunt arises from the popular belief that Elijah comes to aid those in mortal danger. According to a story in the Talmud, Elijah was said to have rescued one Eleazar ben Perata from the Romans and removed him four hundred miles away.400

One man ran, filled a sponge with wine vinegar (15:36). The name of this sour wine derives from the Greek word for sharp (oxys) and was made from water, egg, and vinegar. It was a soldier’s drink. Marcus Cato was said to have called for it when he was in a raging thirst or when his strength was failing.401 The one who went to get the wine may have hoped to give Jesus a spurt of energy to enable him to hold out until Elijah arrived.

With a loud cry, Jesus breathed his last (15:37). “Breathed out” (ekpneueo) is a rare word for death. Scholars have argued that death was caused by (1) a rupture of the heart; (2) asphyxiation as breathing became more difficult; or (3) shock from extreme physical punishment. From carefully conducted experiments, Zugibe refutes the asphyxiation theory and argues that Jesus’ death was caused by traumatic shock from the effects of dehydration and loss of blood.402

The curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom (15:38). Mark may refer to the outer curtain that separated the sanctuary from the outer porch403 or to the inner veil between the Holy Place and the Most Holy Place.404 The high priest on the Day of Atonement could go behind this veil into the Most Holy Place for only a brief moment. The veil was made of the finest wool—blue, purple, and scarlet; and, according to the Mishnah, was one handbreadth thick, forty cubits long, and twenty cubits broad and took three hundred priests to immerse it.405 Josephus, a priest who would have firsthand knowledge of the veil, describes it as

of Babylonian tapestry, with embroidery of blue and fine linen, of scarlet and also purple, wrought with marvelous skill. Nor was this mixture of materials without its mystic meaning: it typified the universe. For the scarlet seemed emblematical of fire, the fine linen of the earth, the blue of the air, and the purple of the sea; the comparison of the two cases being suggested by their colour, and in that of the fine linen and purple by their origin, as the one produced by the earth and the other by the sea. On this tapestry was portrayed a panorama of the heavens, the signs of the Zodiac excepted.406

The veil’s rending may have both a negative and positive significance. Being torn from top to bottom points to its irremediable destruction and to God as the agent. It may signify the end of the Jewish cult and the destruction of the temple. Josephus records strange portents that he claimed gave early warning of the destruction that would later befall the temple. The massive, brass eastern gate of the temple’s inner court took twenty men to close it every evening and fasten it shut with iron bars anchored to solid blocks of stone. Some years before the temple’s destruction, it supposedly opened of its own accord.407 The Lives of the Prophets, compiled by a Jew in the first century A.D. but preserved and edited by Christians, contains the following prophecy attributed to Habakkuk:

And concerning the end of the Temple he predicted, “By a western nation it will happen.” “At that time,” he said, “the curtain of the Dabeir [transliteration of the Hebrew for the inner sanctuary, the Most Holy Place] will be torn into small pieces, and the capitals of the pillars will be removed and no one will know where they are” (12:12).

A Talmudic tradition also connects the rending of the veil with the temple’s destruction. It records the Roman general Titus entering into the Most Holy Place and rending the veil with his sword, and blood poured out.408

The rending of the veil may also be interpreted as a decisive opening. All barriers between God and the people have now been removed (Heb. 10:19–20).

And when the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, heard his cry and saw how he died, he said, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (15:39). Petronius, a courtier of Nero, recounts in his satiric novel, Satyricon, a soldier guarding the crosses of crucified thieves at night to prevent anyone from removing the bodies for burial.409 It is probable that this was not the first crucifixion detail that the centurion had commanded. According to Mark, the centurion witnesses Jesus’ death, not the rending of the veil. Consequently, we should not attempt to place the scene of the crucifixion at a spot where one might be able to see the veil being torn.

After Julius Caesar was deified, his adopted son, Augustus, became widely known as “son of god” (divi filius). It was not a title applied to emperors in general. This soldier transfers the title from the most revered figure in the Roman imperial cult to a Jew who has just been executed. The opening words of the Gospel (1:1) and this confession directly challenge the claims of the imperial cult. Jesus, not Augustus nor any other emperor, is Savior and Lord.410

Some women were watching from a distance. Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joses, and Salome (15:40). Women customarily gathered in groups segregated from men. Magdalene suggests that Mary came from Magdala, three miles northeast of Tiberias and known as Taricheia in Greek. Church tradition says that she had been a prostitute, but there is no evidence in the New Testament for this.

It was Preparation Day (15:42). Mark explains that Preparation Day is the day preceding the Sabbath. Quitting all work on the Sabbath required much forethought and preparation. Before sunset, all business must be discharged, journeys ended, food prepared, and lamps fixed to burn longer since no light could be kindled on the Sabbath.

Joseph of Arimathea, a prominent member of the Council, who was himself waiting for the kingdom of God, went boldly to Pilate and asked for Jesus’ body (15:43). The Romans frequently did not allow the bodies of executed persons to be taken down and buried.411 Philo protested against the prefect Flaccus:

On the eve of a holiday of this kind, people who have been crucified have been taken down and their bodies delivered to their kinsfolk, because it was thought well to give them burial and allow ordinary rites. For it was meet that the dead also should have the advantage of some kind treatment upon the birthday of an emperor and also that the sanctity of the festival should be maintained.

Flaccus gave no orders to take down the bodies of the executed Jews but crucified more instead.412

Deuteronomy 21:22–23 became the basis for the Jewish belief that one was obligated to bury the body of criminals and even enemies on the day of their death. Philo paraphrases the text, “Let not the sun go down upon the crucified but let them be buried in the earth before sundown.”413 Josephus writes about the treacherous attack of the Idumeans in the first revolt when they killed the chief priests and refused to allow them to be buried: “They actually went so far as to cast out the corpses without burial, although the Jews are so careful about funeral rites that even the malefactors who have been sentenced to crucifixion are taken down and buried before sunset.”414

Arimathea may designate that Joseph comes from Ramathaim (1 Sam. 1:1), east of Joppa, or Rathamin to the northwest (1 Macc. 11:34). He is described as someone of high standing and noble repute. He may have been a member of his local ruling body or a member of the council that decided Jesus deserved death. Why would he then wish to claim the body? Joseph is described with emphasis as looking for the kingdom of God, which identifies him as a pious man (see the description of Simeon and Anna, Luke 2:25, 38). The statement that it is already the evening of the Preparation Day, the day before Sabbath (Mark 15:42), provides the motivation for why he wishes to act and act quickly. A body must not be allowed to hang beyond sundown into the Sabbath. Joseph fulfills the pious obligation to bury the dead and thus prevents a body left on the cross from affronting God and defiling the land and the Sabbath (Deut. 21:23).

If Joseph is not a follower of Jesus at this point, it may explain why the women do not come near and assist in the burial but watch from a distance. In Acts 8:2, when Stephen was stoned, pious men, not Christians, buried him and made great lamentation over him. Regarding Jesus’ burial, Acts 13:29 asserts that when “they had carried out all that was written of him, they took him down from the tree and laid him in a tomb.” The context implies that enemies of Jesus buried him.

Ordinarily, family or friends requested the body of one who was executed (see the disciples of John the Baptist, 6:29). Yet Jesus’ disciples do not do this. That Joseph “went boldly” to ask Pilate for the body suggests that the request involved some risk. Jesus has been executed for treason as the king of the Jews. To ask for the body of one guilty of maiestas could be looked upon as sympathizing.

In Matthew 27:57, Joseph is identified as a disciple and rich. The aorist verb, however, may be translated that he became a disciple at a later time and need not mean that he was counted among the disciples when he buried Jesus. In Luke 23:50–51, he is identified as a good and righteous man, who did not consent to their plan and action and who was waiting for the kingdom of God. In John 19:38, he is identified as a secret disciple. Possibly, Joseph became a follower of Jesus after the resurrection, which explains why his name was remembered in the tradition.

So Joseph bought some linen cloth, took down the body, wrapped it in the linen, and placed it in a tomb cut out of rock (15:46). “Some linen cloth” translates the word sindon (see 14:51–52). It may refer to pieces of cloth to wrap the body but more likely refers to a single piece of linen cloth not unlike the spurious Shroud of Turin.

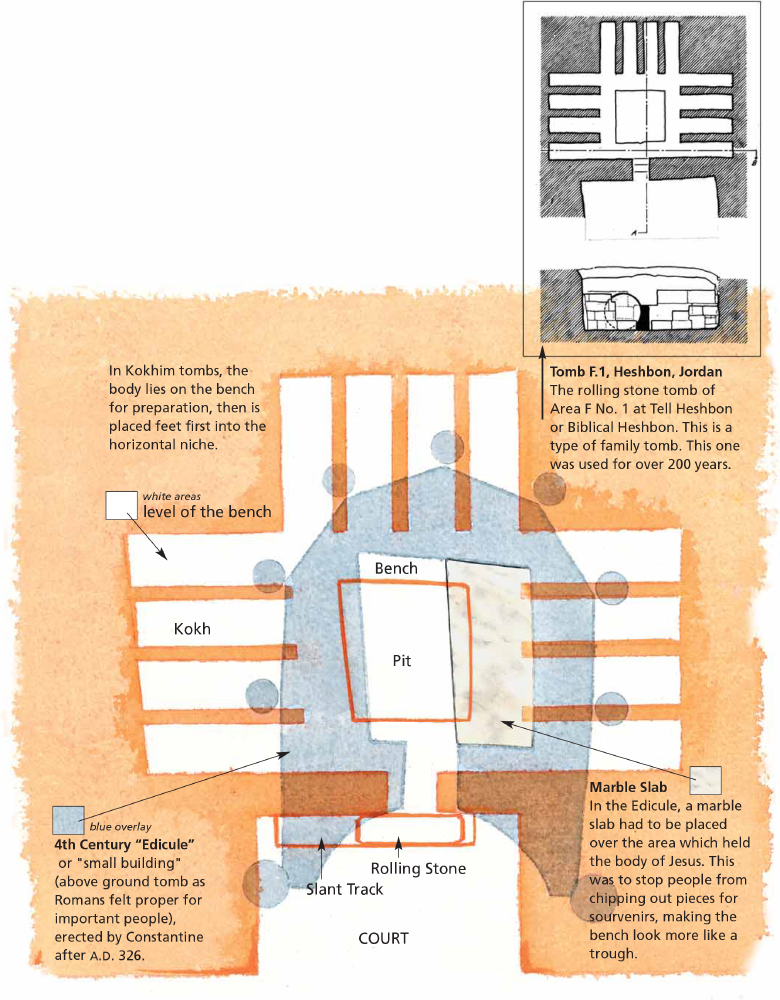

ROCK-HEWN TOMBS

Examples of Roman-era rolling stone tombs in Israel.

The surviving tombs from this period appear to belong to wealthier families. Most of the population apparently were buried in “simple shallow pits” that have not survived.415 Wealthier Jews practiced secondary burial. When the flesh had decomposed, the bones were carefully gathered up and placed in an ossuary box, the larger bones on the bottom and smaller bones on top. This practice allowed tombs to be reused. The coffin-less body would be placed in a niche (kokh, up to 2 ft wide and 7 ft deep) cut horizontally into the wall of the tomb chamber. Another type of tomb had trough-like shelves hewn along the sides of the chamber with an arched ceiling (acrosolinium). A third type of tomb had a low bench cut around three sides of the chamber. Mark’s account of the angel sitting inside on the right (16:5) seems to describe a tomb with a bench, and John 20:6, 8 suggests it has an anteroom.

Then he rolled a stone against the entrance of the tomb (15:46). The tombs in this period had small, low openings into cave-like chambers that were closed with stone blocks (see John 11:38–39) or with rolling stones (like a mill stone) in slanted tracks. Sealing the tomb prevented the body from being disturbed and shut out dirt. But it also shut down its potential defiling effects. A tomb with a door was ruled as not spreading defilement on all sides, and one could safely walk above it without being defiled.

TOMB OF JOSEPH AND THE EDICULE

Looking at the present edicule, it is impossible to know what the original tomb of Jesus looked like. We can now reconstruct that original by comparison with 63 other round-stone tombs from the time of Christ. Probably the closest of these 63 would be Heshbon Tomb F.1 which of all 63 most closely follows the plan found in the Mishnah Baba Bathiza 6:8. This form temporarily died out at A.D. 70 with the Roman destruction, but was brought back in the 4th century A.D.

A discussion in the Tosepta describes the case of a man who died on the eve of Passover. To bury him, the women tied a rope to the rolling stone and the men pulled on the rope from outside to move it. The women then entered the tomb and buried the man. By not touching directly the body or the rolling stone, the men remained in a state of purity and were able to eat the Passover.416

The tomb in which Jesus was laid had to be nearby since the body had to be buried quickly before the Sabbath. Visitors to Jerusalem are frequently shown the garden tomb, discovered in 1867, as the site of Jesus’ burial. It is a more peaceful and picturesque locale than the Holy Sepulchre church and definitely outside the city wall. The archaeological evidence, however, rules it out, since it was hewn in Iron Age II (eighth to seventh century B.C.). No other tombs that can be dated to the time of Jesus have been uncovered in this area, and it differs from other excavated burial caves that date from the first century.417