Unfortunately there is no reliable image of Spenser, or of his wives or descendants. This is not really surprising: there are no positively identified images of many of his contemporaries. We have no real idea what Thomas Deloney, Robert Greene, Gabriel Harvey, Thomas Lodge, Christopher Marlowe (arguably), Thomas Middleton, Thomas Nashe, Robert Southwell, and John Webster looked like. We cannot be sure about Shakespeare, although the funeral monument in Stratford-upon-Avon is probably based on observations drawn from life.1 In any case, Shakespeare died late enough to have caught the vogue for producing civic portraits of writers.2 We have a number of reliable portraits of early seventeenth-century authors, including George Chapman, Samuel Daniel, John Fletcher, and Ben Jonson. However, only a few unusual examples survive from the late sixteenth century, most significantly the portraits of John Donne and Michael Drayton, who had himself painted as poet laureate in 1599, the year that Spenser died, the clear message to the knowledgeable viewer being that Drayton was claiming Spenser’s garland.3

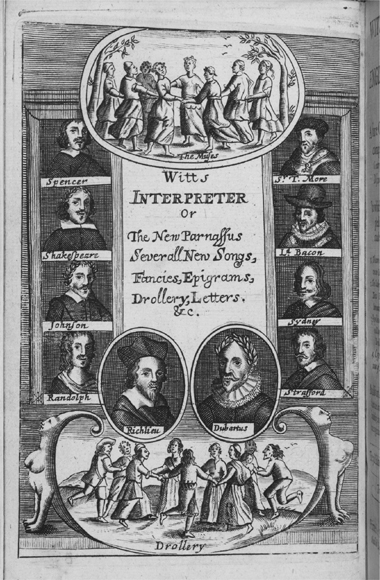

No printed portrait of Spenser appeared alongside work published in his lifetime. But in the mid-seventeenth century an imaginary engraved portrait appeared alongside other portraits of writers on the title pages of John Cotgrave’s survey of the written achievements of the English gentry, Wits Interpreter, the English Parnassus (1655) (Figure 12). The title page also includes thumbnail portraits of Geoffrey Chaucer, William Camden, Francis Bacon, and others, several of which are based on authentic known portraits of these sitters. The shadowy figure identified as Spenser shows a generic seventeenth-century long-haired man with a moustache, wearing costume from the 1640s. As this date is forty years after Spenser’s death, it is clear that the likeness could not be based on an authentic image and that the motive was largely an illustrative device; simply a shorthand means to associate the work with some major literary figures. Another similar portrait also identified as Spenser was reproduced on the frontispiece to the second edition of Edward Phillips’s The New World of English Words, or A General English Dictionary (1658).4 This portrait was probably inspired by the earlier print and shows a more clearly rendered man between two pillars with the same long hair and moustache (Figure 13), again one portrait as part of an ensemble of other renowned writers.

The first portrait of Spenser appeared soon after the publication of Jacob Tonson’s (1655/6–1736) edition of Spenser’s Faerie Queene in 1715, nearly a hundred and twenty years after the poet’s death, when the painter George Vertue (1684–1756) claimed to have discovered one in 1719 in the possession of John Guise (1682/3–1765) (Plate 45).5 Guise left his collection of 250 paintings to Christ Church, Oxford, but there is no record of any being of Spenser.6 The original has disappeared, but Vertue made what appears to have been a copy in 1727, which is of the same type later identified as the Oxford/Chesterfield portrait of Spenser, of which numerous copies exist, so this ‘original’ may well have been simply a copy of that painting or another version of it.7 The timing of the discovery is suspicious and, as David Piper has argued, the relationship of the portrait ‘to Spenser himself remains doubtful—not only because of its late emergence, but because of the clash of inscriptions of date and age that the versions bear’.8 Another copy, painted by Benjamin Wilson (1721–88), was given to Pembroke College by William Mason (1725–97) in 1771, the year his great friend, another fellow of the college, Thomas Gray, died.9 In fact, it seems clear that the surviving versions are later seventeenth century or even eighteenth century in origin. Therefore, it is possible that no original ever existed, but instead that the portrait type is a fabrication, perhaps like that of the so-called ‘Soest’ portrait of Shakespeare which dates from c.1667 and which shows Shakespeare as a handsome and notably romantic figure.10 Moreover, the style of dress in the Spenser portrait (particularly the doublet with wide shoulder guards) dates from c.1615–20 which clearly indicates that the original could not have been produced during Spenser’s lifetime. Therefore, the portrait type was either based upon a portrait of a Jacobean man whose likeness became associated with Spenser at an early date, or was an invented portrait to create a suitably sensitive portrait of Spenser at an opportune moment.11

The desire to find a picture of Spenser was clearly acute in the early eighteenth century, fuelled no doubt by Tonson’s own interest in the subject. Tonson, who almost single-handedly changed the nature of publishing by producing quality editions of the finest authors of his age to help bestow dignity upon the writing profession, had himself portrayed holding his own volume of Milton by Sir Godfrey Kneller.12 Along with Sir John Somers (1646–1723), he helped to revitalize Spenser’s reputation through publishing finely produced editions of his poetry.13 Tonson dedicated his edition of Spenser’s Faerie Queene to Somers, who was then painted by Kneller for the Kit-Cat Club holding the book in 1715 or 1716, as soon as it appeared.14 The Kit-Cat Club was named after the mutton pies of Christopher Catling, which the group of artists, writers, intellectuals, and politicians who met in central London taverns to discuss matters of importance, consumed during their meetings. It had been founded by Tonson and other intellectual Whigs eager to use their influence to transform the cultural politics of the nation. They held Spenser, seen as a Protestant, Whig poet, in especially high regard. Tonson’s edition of Spenser did not include a picture of the poet, but showed a group of gentlemen and ladies staring avidly at Spenser’s tomb in Westminster Abbey, a sign of his growing celebrity in the period and the need to have tangible remains of the famous dead (Figure 11). This lack of a secure image of the poet undoubtedly fuelled the need to find a portrait, especially as ones of Milton were relatively easy to procure. We should, then, not be surprised that a portrait turned up soon after Tonson’s edition, especially as it was found by the antiquarian George Vertue, who was close to the family of one of the central members of the club, Robert Walpole (1676–1745), whose son, Horace (1717–97), purchased many of his pictures.15

The first biographer to be able to locate a portrait of Spenser was Thomas Birch, author of a substantial life as a preface to his 1751 edition of the Works. Birch declares that ‘An original picture of him is still in being, in the neighbourhood of his seat, at Castle-Saffron [just east of Doneraile], the House of JOHN Love, Esq.’.16 A letter published in the Gentleman’s Magazine in March 1818 confirms that the picture was removed at some point in the late eighteenth century.17 It has never been recovered and we have no knowledge of whether Mr Love had a copy of an existing portrait or a new one that has now been lost.

In 1776 the discovery of another supposed likeness of Spenser was announced by the traveller Thomas Pennant (1726–98), when he visited Dupplin Castle, near Perth. This was the ‘Kinnoull’ portrait, named after the earls who then owned the estate (Plate 46). There was no obviously immediate reason for a picture at this time, as there had been in the aftermath of the Tonson edition. It is worth noting that Spenser’s role as the inspiration behind the Gothic revival of the later eighteenth century had been cemented by the publication of William Kent’s startling illustrations in Birch’s edition of The Faerie Queene and, immediately before that, James Thomson’s Spenserian tale, The Castle of Indolence (1748).18 Moreover, Pennant was a close friend of the naturalist Gilbert White (1720–93), White’s letters to Pennant making up a substantial part of White’s extraordinarily popular The Natural History of Selbourne (1771). White had a spaniel called ‘Fairey Queene’, a sign of how significant Spenser was in so many diverse ways to such groups of cultural gentlemen, and how he helped to form their intellectual horizons.19 Spenser was more popular in the second half of the eighteenth century than he had been at any time before, his work, in particular The Faerie Queene, appealing to Augustans and Romantics alike.20 The absence of a portrait of Spenser was, if anything, even more frustrating for readers when Pennant announced his find.

Figure 12. John Cotgrave, Wits Interpreter, the English Parnassus (1672 edition), title page. Reproduced with kind permission of the British Library.

Figure 13. Edward Phillips, The New World of English Words (1658), frontispiece. Reproduced with kind permission of the British Library.

The ‘Kinnoull’ sitter inspired flights of Victorian fancy: G. W. Kitchin, who edited The Faerie Queene, Book I, characterized this image of Spenser as ‘A refined, thoughtful, warmhearted, pure-souled Englishman’.21 The ‘Kinnoull’ portrait shows a man in his middling years wearing a white ruff edged with fine lace and a black cloak in a three-quarter pose facing right. The ruff probably dates from the first decade of the seventeenth century, but could conceivably be very late 1590s.22 The painting may date from around 1600, although dendrochronology would be needed to be certain of its date. The identification of Spenser, rather than any other well-to-do member of the middling sort, gentry, or a minor courtier, lacks any evidential basis, other than tradition, and the elaborate lace ruff would seem to indicate a sitter rather more wealthy than the poet.23 There is also little to be said for the case of the Fitzhardinge miniature, attributed at one time to Nicholas Hillyard, but clearly not his work. Little is known about the provenance of this portrait, but it is extremely unlikely to be Spenser.24

The evidence of portraits of Spenser existing after the early eighteenth century does not add much to our knowledge. Thomas Birch does not provide any details of the portrait that was discovered at Castle Saffron and we do not know its location now.25 Attempts to track it down in the early nineteenth century proved fruitless. There is a record of another portrait, perhaps the same one, in the possession of Edmund Spenser the third, the great-great-grandson of the poet, which was then passed on to a Mrs Sherlock, his granddaughter. This has also disappeared.26 An exchange between interested parties in 1850–1 led a correspondent, ‘Varro’, to claim that he was ‘well acquainted with an admirable portrait of the poet, bearing the date 1593, in which he is represented as a man of not more than middle age’.27 When challenged to produce his evidence by the original correspondent, ‘E. M. B.’, he failed to reply, but it is most likely that he was referring to the Chesterfield portrait.28 The exchange further reveals the history of uncertainty surrounding portraits of Spenser and the lack of confidence that a true likeness exists. When working on his biography of Spenser in the 1940s A. C. Judson had to work hard even to find the Fitzhardinge miniature as well as the Kinnoull portrait, more evidence that images of the poet do not have a definitive status.29

There are some later portraits but these are all oddities. A small canvas in the Plimpton collection at Columbia University, with the name ‘Spencer’ written beside the head and shoulders of the figure, is clearly a crude work based on the Chesterfield portrait, showing the poet at a slightly younger age. It was probably painted in the early nineteenth century (Plate 47).30 Another, a mid-Victorian work held in the National Portrait Gallery, shows Spenser greeting Shakespeare, each bowing with great formal reverence to the other. The painting is part of a general effort of the nineteenth-century imagination to think of the great writers of Elizabethan England in productive conversation with each other. As well as Shakespeare, Spenser is most commonly imagined in conversation with Sir Walter Ralegh, as in the charming print in H. E. Marshall’s English Literature for Boys and Girls (Figure 1). A tradition has developed in which Spenser is represented as a small man, with a neat beard, resembling the figure in the Chesterfield portrait rather than the more angular-featured man in the Kinnoull portrait. Unfortunately, this image has no serious claim to authority, although it is in keeping with the most authentic description we have of Spenser: ‘a little man, wore shorte haire, little band and little cuffs’.