Menga (Andalusia, Spain): biography of an exceptional megalithic monument

Abstract

Menga was discovered for modern science in the 1840s, when Rafael Mitjana carried out excavations that he reported in his Memoria. The booklet soon circulated internationally, giving this great megalith an early fame. Yet, as written accounts dating to the 16th through 18th centuries AD and other pieces of evidence attest, Menga had never been really ‘forgotten’. Archaeological excavations carried out in the late 20th and early 21st centuries have provided evidence suggesting that, since its construction in the Neolithic period, and during later prehistory, Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Menga was used as a sacred building and burial ground. This paper brings together, for the first time, some of the evidence available in order to understand Menga’s outstanding biography, spanning almost 6000 years. The archaeological data currently available is fragmentary and largely unpublished, but taken together, it tells a remarkable story about the inception, design, and long life of what possibly is the most fascinating megalithic monument of Iberia.

Keywords: Neolithic, Copper Age, Bronze Age, Antiquity, Middle Ages, megalith, burial, landscape

Introduction

Located in the plain of Antequera (Málaga), on the northern side of the Baetic mountain range, Menga is possibly the most famous megalithic monument in Iberia. As Sánchez-Cuenca López (2012) showed in his historiographic review, following its discovery for archaeology as a scientific discipline by Mitjana (1847), Menga became a reference for the study of the megalithic phenomenon worldwide throughout the 19th century. There is no doubt that its exceptional size and architectural features played a major part in its early fame within contemporary archaeological knowledge (Figs 1.1 and 1.2).

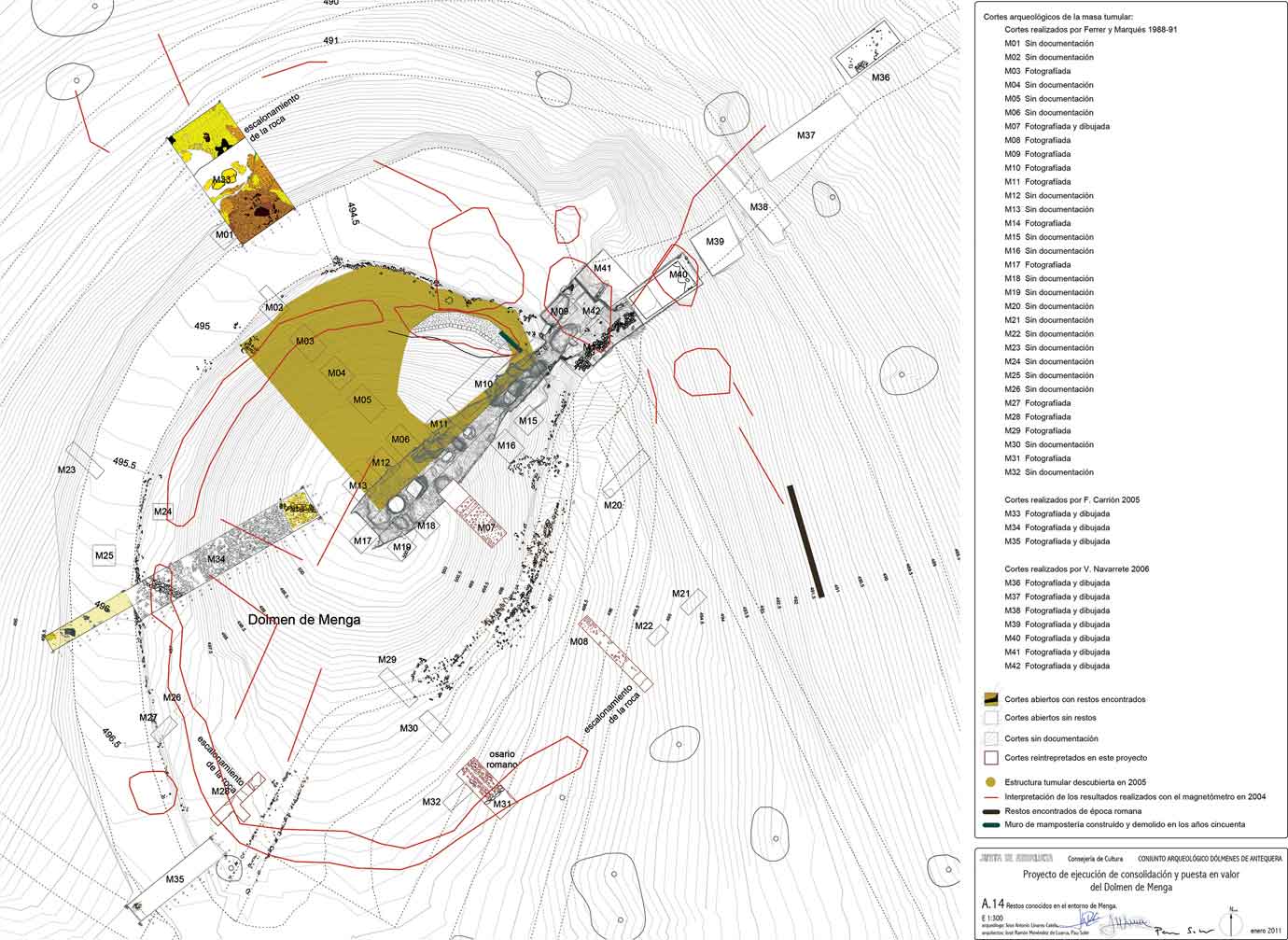

Writing a biography of Menga is a very complex task. Firstly, it has been the target of a significant number of interventions since it was first discovered, the more recent and extensive of which remain largely unpublished (Fig. 1.3).1 Secondly, numerous indications suggest that Menga has been visited, frequented and used, on a practically continuous basis since it was first built. It was never buried underground, away from human interest and curiosity, as so many other prehistoric monuments were. In addition, the history of Menga is inherently linked to the other two large monuments that form the megalithic complex of Antequera – Viera and El Romeral – as well as other important prehistoric sites in the surrounding area, the most noteworthy being La Peña de los Enamorados. Combined, these factors make its biography a fascinating, albeit particularly difficult, case study.

This paper is a condensed English version of a larger work dedicated to the biography of Menga, to be published in Spanish, and is based on a thorough examination of published data, various unpublished reports and information obtained directly from excavators (García Sanjuán and Lozano Rodríguez, forthcoming).

Before Menga

Excavations conducted over the last three decades found evidence suggesting prior occupation on the hill on which Menga and Viera are located. Details of what this activity consisted of are not known, as the first task the builders of Menga undertook was the levelling of the entire construction area (Ferrer Palma et al. 2004, 187–189). There are three pieces of evidence for this occupation: (i) the lithic and ceramic artefacts found within the fill used for the Viera and Menga tumuli, which came from deposits of a previously existing settlement (Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a, 184); (ii) the negative structures detected outside Menga (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006a, 23); and (iii) the single inhumation found in the south-western quadrant of Menga’s mound (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006a, 22–23). Unfortunately, attempts to radiocarbon date the very poorly preserved human remains of this single inhumation have been fruitless due to a lack of collagen.

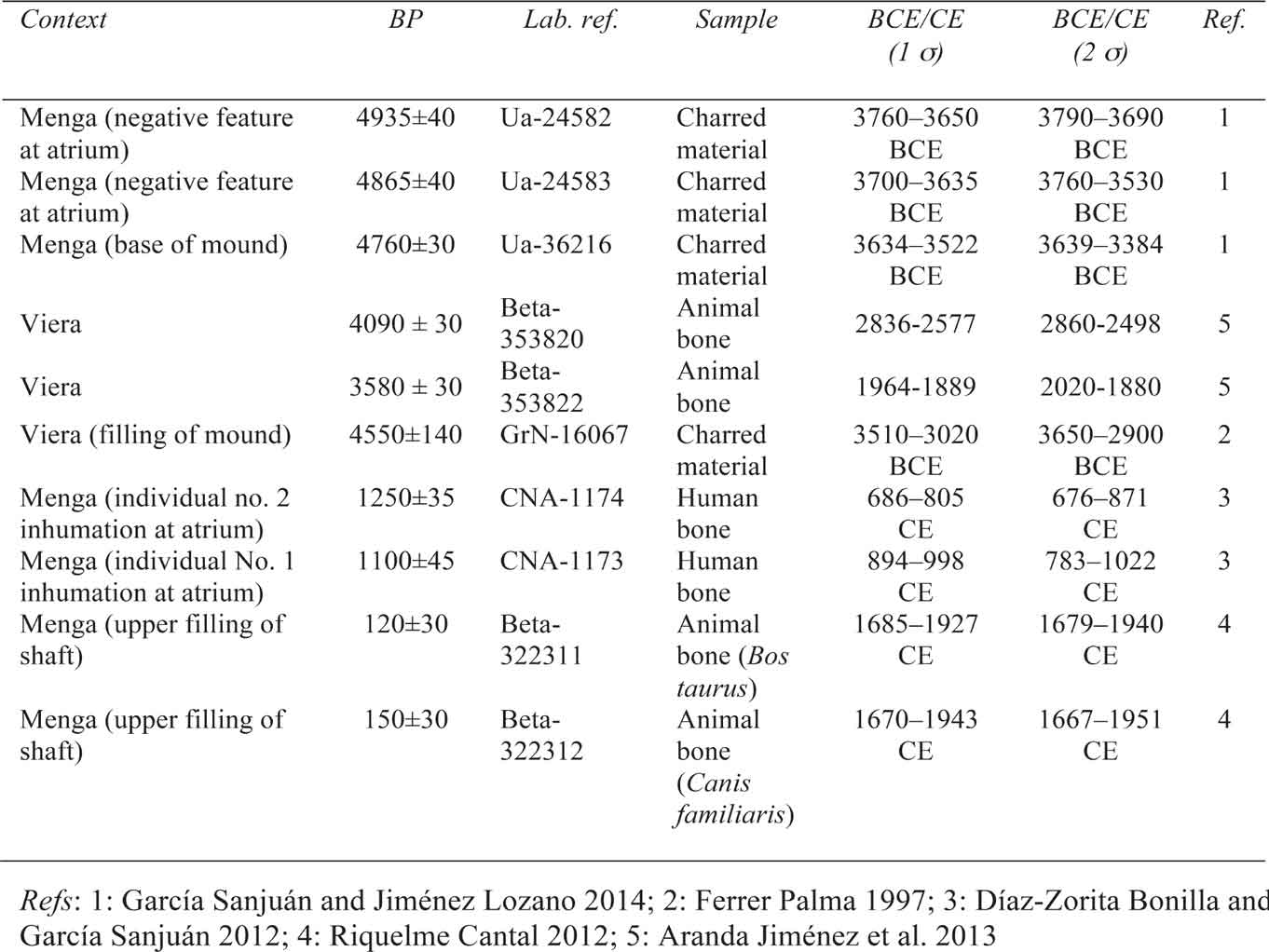

When was Menga built? There are currently three radiocarbon dates for this monument that fall within the late prehistoric period (Table 1.1), all obtained from charred material. Two were obtained from samples collected inside a pit located in the monument’s atrium that contained carbon remains and three fragments of handmade pottery, including a rim (Navarrete Pendón 2005, 16–17). The dates were 3790–3690 cal BC and 3760–3530 cal BC (all calibrated dates quoted to 2σ) (Table 1.1). The third radiocarbon date was obtained from a sample retrieved from the base of the tumulus in Sector D of the excavation undertaken by the University of Granada in 2005–2006. The age of this sample is 3639–3384 cal BC (Table 1.1): it is broadly contemporary with the two other samples.

Fig. 1.1: Menga from the northeast. Photo: Leonardo García Sanjuán.

Fig. 1.2: Interior of Menga, looking inwards from the entrance. Photo: Miguel Ángel Blanco de la Rubia.

Table 1.1: Radiocarbon dates available for Menga and Viera

The biological nature of the dated carbonised organic matter has not been established in any of the three cases. If they are wood, the samples could be older than the contexts or events supposedly dated. Nevertheless, the chronology of these dates quite consistently places them in the second quarter of the 4th millennium cal BC (c. 3800–3400 cal BC), within what could be considered an early stage of megalith construction in southern Spain. All three dates (especially that from the tumulus) constitute post quem chronological evidence for the building of Menga. Given that samples taken from the trenches or foundation pits of the orthostats or pillars have not been dated, there is no direct data that would enable us to establish when construction started, or how long it lasted (if this was a process that extended over time).

Indirect evidence regarding the date of construction of Menga comes from one of the three currently available C14 dates for Viera (GrN-16067). The tumulus of the latter lies adjacent to that of Menga and gave a calibrated age of 3650–2900 cal BC (Table 1.1). According to the excavators, this sample dates a surface that existed before the construction of the mound: therefore, again, the date only has a post quem value in relation to the construction of Viera (Ferrer Palma 1997a, 135). Moreover, in this particular case, the value of the date for interpreting the construction of the monument is limited by its high standard deviation. What seems clear is that this date points to a later chronological horizon than that reflected by Menga’s three dates. This is consistent with the observation that, from a mechanical standpoint, the space occupied by Viera was needed to construct Menga, as it is the natural entry point from the quarry area for its stone blocks (Lozano Rodríguez et al. 2014). Collectively, this suggests that Menga was built before Viera.

The radiocarbon data currently available are of little help with regard to how long the construction process of Menga took. However, architectural analysis yields three interesting indications: (i) the orthostats are supported one on top of another, with an identical angle of around 4°; (ii) the capstones overlap one another; and (iii) the tumulus does not show any lateral change of construction phases. Taken together, these indications suggest that Menga was the result of a single architectural project, carried out over a period of time that we are currently unable to determine. However, as part of its long biography, it is possible that some external orthostats, corresponding to the atrium, were removed at some unspecified point in time (García Sanjuán and Lozano Rodríguez, forthcoming). The architectural remains found in the atrium, particularly the wall that projects the southern hemisphere of the monument several metres to the east, could indicate the existence of “additions” to the original project but, unfortunately, the data currently available do not enable us to be more specific.

Fig. 1.3: General plan of Menga and its mound showing excavations by the University of Málaga (1988–1991), V. Navarrete Pendón (Spring 2005) and University of Granada (2005–2006). Source: Courtesy of José Ramón Menéndez de Luarca and Pau Soler

An extraordinary design

Menga stands out as an exceptional megalithic monument in both the scale of its construction and its design. It is basically the largest and heaviest megalithic monument on the Iberian Peninsula, comparable only to Anta Grande de Zambujeiro (Évora, Portugal). Its dimensions are remarkable, with a total length of the inner space plus atrium of 27.5m, a height that rises from 2.7m at the entrance to 3.5m at the top, and a width of 6m at its widest point inside (Marqués Merelo et al. 2004, 174; Márquez Romero and Fernández Ruiz 2009, 139). Menga’s mound is almost 50m across and contains approximately 3000m3 of earth and stones, carefully placed in alternating layers (Ferrer Palma 1997b, 359).

But what makes Menga extraordinary is the size and weight of its stones, including 24 orthostats, three pillars and five capstones. The total combined weight of orthostats, pillars and capstones is 835.7 tonnes, with the capstones weighing 44, 51, 68, 87 and 149 tonnes (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006b, 132). Although this type of estimate is virtually non-existent for other Iberian megaliths, capstone 5 of Menga with its dimensions of 6.05m wide, 7.20m long and 1.72m at its thickest, and weighing at least 150 metric tonnes, is possibly the largest and heaviest stone ever moved in later prehistoric Iberia within the context of the megalithic phenomenon.

Another exceptional element of Menga’s architecture is the shaft discovered at the back of the chamber in 2005. However, in light of the difficulties in establishing its chronology, for now it is impossible to know whether this element was designed and built as part of the original construction plan of Menga or whether it was added at a later date. Given the complexity of the discussion needed to evaluate the different sources of indirect evidence that could help to establish its chronology, the Menga shaft is not dealt with in this work – a detailed discussion is available in García Sanjuán and Lozano Rodríguez (forthcoming).

Altogether, it appears that the creators of Menga set out to make a special and enduring work that would live on in the memory of generations to come. In its dimensions and scale, it was conceived as a monument that would surpass all that was previously known. Its culmination must have been a memorable event, not only socially and ideologically, but technically and architecturally, too. Menga surely left a recognisable mark on the collective imagination of the Neolithic inhabitants of the region, and perhaps further afield. In this regard, the aim of those who built Menga, to create something unrepeatable and famous, is so obvious that it seems difficult to avoid the explanation that the Antequera plains already had an earlier special significance. This leads us to the implications of Menga’s landscape setting.

An extraordinary event?

Interesting indications in relation to the genesis of Menga can be drawn from another of its architectural features: its axial orientation. Menga was not oriented to sunrise, as is the case with 95% of the megalithic monuments in southern Iberia (Hoskin 2001, 92–93). Rather it is slightly to the north of the summer solstice (specifically at 45°), towards La Peña de los Enamorados, a mountain that stands out in the Antequera plain. Survey work has demonstrated that Menga’s axial orientation is specifically directed to the north face of La Peña de los Enamorados, where there is a cliff with an almost perfectly vertical drop of almost 100m. At the foot of this impressive cliff there was a noteworthy area of activity at the end of the Neolithic. This included the small shelter of Matacabras, with schematic-style rock art, and the Piedras Blancas I activity area, associated with a scatter of microliths (García Sanjuán and Wheatley 2009; 2010; García Sanjuán et al. 2011b). Although the functional nature and chronology of this sector of La Peña de los Enamorados still needs to be established more accurately, as yet unpublished studies suggest that the site of Piedras Blancas I may have been monumentalised during the Neolithic period (Fig. 1.4).

It seems implausible that a feature with such a powerful symbolic weight – the orientation – was left to chance: therefore in orienting Menga towards the Piedras Blancas I and Matacabras sector of La Peña de los Enamorados, the architects commemorated a site that already had a very special ideological and symbolic significance before the dolmen was built. Such significance prevailed over the solar orientation usually applied to megalithic monuments in Neolithic Iberia. Menga was therefore configured as a compass that not only pointed towards space but also to time, to a place with an ancestral importance for those who built it. In this regard, the physical design of Menga itself has a mnemonic purpose, suggesting that its biography started long before its construction (García Sanjuán and Wheatley 2010, 27–31). This can also be connected with the data regarding the previous occupation of the hill on which it was built, discussed above. It is possible that one of the reasons for Menga’s exceptional design was that there was an older tradition that made the Antequera region, or some specific site within it (perhaps La Peña de los Enamorados), a well-known social and ideological focus whose importance and fame needed to be matched. We must also consider the fact that the Antequera plain was (as it is today) a strategic transit point or crossroads in southern Iberia, between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, between the Guadalquivir river basin and the heart of the Baetic mountain range. Today, Antequera is the midpoint between Sevilla and Granada and between Málaga and Córdoba.

Fig. 1.4: Monolith at Piedras Blancas I, at the foot of the northern cliff of La Peña de los Enamorados, showing (left) Leonor Rocha and (right) the late Pedro Alvim, University of Évora (Portugal), March 2009. Photo: Leonardo García Sanjuán.

It is therefore possible to take a fresh look at recent geological research, which indicates that a massive earthquake may have hit the Málaga region between the late 5th and early 4th millennia cal BC. Evidence of this event has been found in the speleothem records of the El Aguadero sinkhole (Periana, Málaga), located 50km to the east of Antequera (Clavero Toledo 2010). Specifically, the radiocarbon date obtained from a stalactite (Beta-222473) places this earthquake in or shortly after 5110±70 BP, i.e. 4045–3713 cal BC (Clavero Toledo 2010, 136). The chronology of this earthquake is interesting when related to the radiocarbon dates of Menga and Viera, and particularly in relation to the Neolithic occupation of El Toro cave, which, lying just 8km to the south of Menga, is one of the oldest Neolithic settlements in southern Iberia (Fig. 1.5).

Of the 29 radiocarbon dates published for El Toro cave, the oldest 24 are chronologically compact. They represent its probably uninterrupted occupation from the mid-6th to the very end of the 5th, or start of the 4th millennium cal BC. Of the five remaining dates, the standard deviation of one is too large while the other four fall within the mid-4th, 3rd, and 2nd millennia BC, clearly representing a very different – more sporadic – usage pattern from that seen in the Neolithic period. This radiocarbon series seems to demonstrate a discontinuity in the very late 5th or early 4th millennium, precisely when the above-mentioned earthquake may have occurred. In addition, the excavators of El Toro cave noted a dramatic change in the topographic conditions and habitability of the cave, including the lasting blockage of the main entrance to the cavity, and attributed it to an earthquake (Cámalich Massieu et al. 2004, 297). The precise date of the collapse and blocking of the entrance to El Toro is, however, unknown. Since no absolute date for the earthquake was available when the results of the excavation were published by Camalich Massieu et al. (2004), the excavators suggested that the earthquake that caused the blocking could have occurred in the 3rd millennium BC. It was only later that the publication of the El Aguadero sinkhole date and its comparison with the El Toro C14 sequence led us to suggest that the date of that event may in fact have been considerably earlier.

If the apparent match between the discontinuity in the use of El Toro seen in the C14 dates and the possible date of the El Aguadero earthquake holds true, it could have some bearing on Menga’s biography. A catastrophic event of such magnitude must have had a severe impact on the community occupying El Toro cave, and maybe other Neolithic communities in the region, leading to changes in their living conditions and land occupation strategies – perhaps also affecting the Piedras Blancas I area of activity at La Peña de los Enamorados.

Later prehistory

As Menga seems to have been an “open” monument throughout its entire life history, the vestiges of its use during the Neolithic, the Chalcolithic, and the Bronze Age seem to have been almost completely erased by the actions of subsequent visitors and users. In his Memoria, Mitjana reported that, contrary to his expectations, there were no remains of “cadavers” or “urns” (Mitjana 1847, 19) suggesting that he saw no evidence of prehistoric funerary activity at Menga. The excavations undertaken by the University of Málaga at the end of the 20th century led to the same conclusion (Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a, 181–182).

Fig. 1.5: Summed distributions of the radiocarbon dates available for Cueva del Toro, Menga and Viera. Total number of dates in brackets. In red: distribution of date Beta-222473 from one stalactite in the El Aguadero sinkhole. Diagram by David W. Wheatley and Leonardo García Sanjuán.

Fig. 1.6: Artefacts attributed to Menga in the Málaga museum. Photo: Leonardo García Sanjuán.

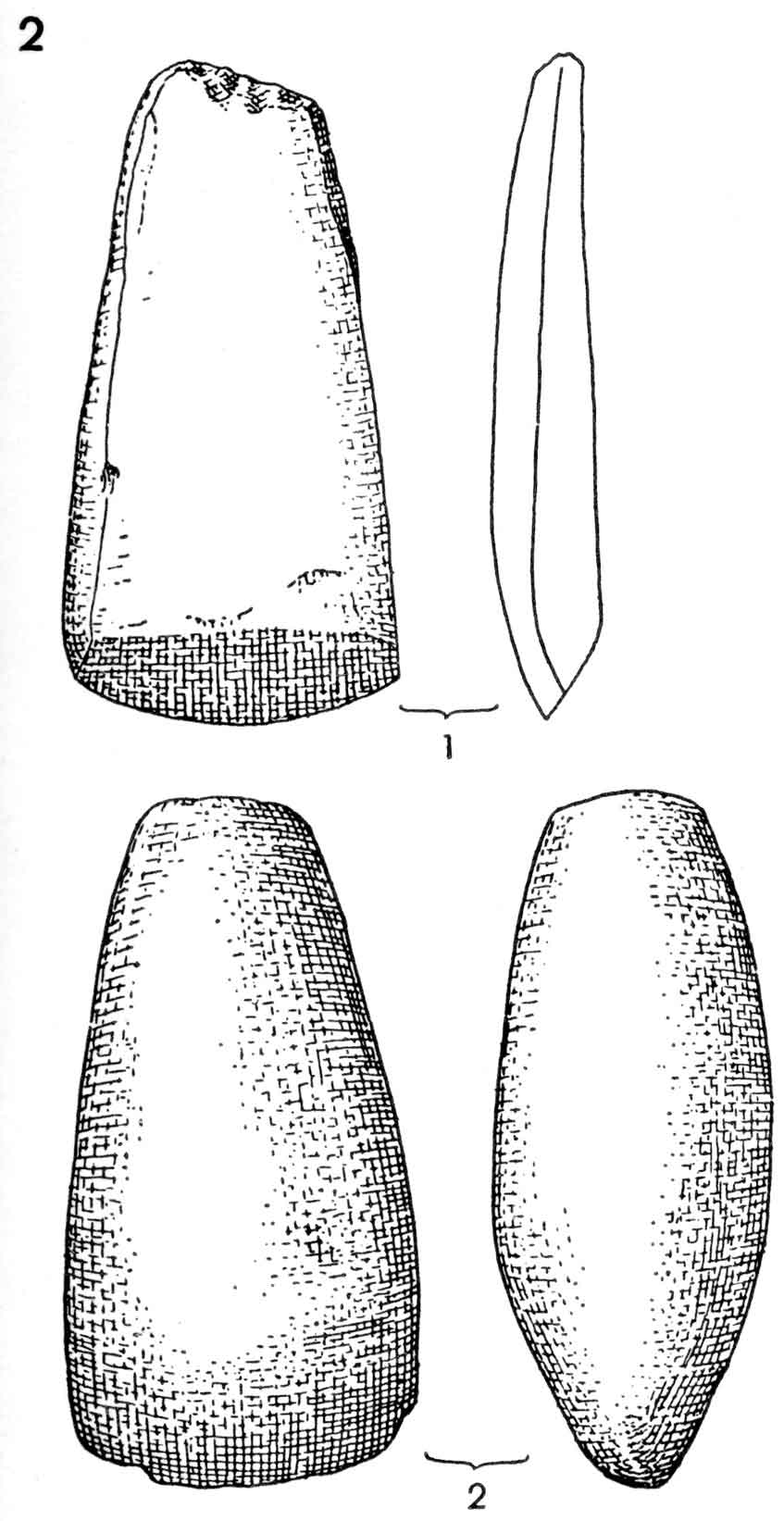

The only prehistoric materials officially attributed to Menga are now in the Málaga museum, donated by Manuel Gómez Moreno in 1945. These consist of a polished axe-head, three blades, and two retouched flint flakes (Figs 1.6 and 1.7). Georg and Vera Leisner (1943, pl. 58) attributed a polished adze and axe-head to Menga, although, due to the schematic nature of their drawing, the axe-head cannot be linked with the one housed in the Málaga museum with certainty. However, a recent review has identified some ambiguities and problems with the attributions of the materials in those old museum collections (Aranda Jiménez et al. 2013, 239). In any case, the finds are not necessarily of Neolithic date: according to their morphology and characteristics they could also be from the Chalcolithic.

There is only indirect evidence on the use of Menga in the Chalcolithic, a period of intense occupation in the surrounding Antequera plain, as exemplified at Cerro de Marimacho, a mere 200m to the east of Menga and Viera (Leiva Riojano and Ruiz González, 1977; Ferrer Palma et al. 1987a; Marqués Merelo et al. 2004b, 242), and at other nearby sites. Further indirect evidence comes from Viera, in particular from a C14 date (Aranda Jiménez et al. 2013), and from the 8cm long copper awl or punch attributed to this dolmen.2

Similarly, there is no direct evidence of how Menga was used during the Bronze Age. Nevertheless, in the province of Málaga, and in the neighbouring province of Granada, there is clear evidence of megalithic sites being intensely reused during this period (Ferrer Palma et al. 1987b; Fernández Ruiz et al. 1997; Fernández Ruiz 2004; Márquez Romero 2009, 214–218; Márquez Romero et al. 2009; Aranda Jiménez 2013), including Viera itself (Aranda Jiménez et al. 2013). It therefore seems highly unlikely that Menga was not used as a sacred and/or burial site by the local Bronze Age populations, although we do not have direct proof at present.

Fig. 1.7: Artefacts attributed to Menga by the Leisners. Source: Leisner & Leisner, 1943: Plate 58.

Fig. 1.8: Roman inhumation tombs discovered in 1988 by the University of Málaga near the Antequera-Archidona road, at the edge of the archaeological enclosure surrounding the dolmens of Antequera. Photo: Rafael Atencia Páez.

Fig. 1.9: Roman ‘ossuary’ discovered in 1991 in the tumulus of Menga by the University of Málaga. Photograph: Ignacio Marqués Merelo.

The publications available for the University of Málaga’s excavations in the 1980s and 1990s report no Iron Age materials in Menga. However, the unpublished reports of the 2005–2006 excavations mention fragments of orientalising-style pottery (Navarrete Pendón 2005, 20), as well as numerous Late Iron Age pre-Roman pottery fragments (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006a, 44). The practices that took place in the area surrounding Menga in the Iron Age are unknown.

Roman times

The excavations carried out in the late 1980s and early 1990s identified several Roman graves in the surroundings of the Menga and Viera tumuli (Ferrer Palma 1997a, 143; 1997b, 356; Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a, 184; Ferrer Palma et al. 2004, 207) (Fig. 1.8). In 1991, a Roman grave was found at the southwestern edge of the Menga mound, practically in the contact area with the Viera mound (Fig. 1.9). This grave, embedded in the mound’s stone filling, had a cover made of large ceramic tiles that protected a small ossuary. Numerous fragments of wheel-thrown pottery were found very close by, including several remains of terra sigillata and a small piece of Roman glass.

The excavations accompanying the restoration of Viera in 2003 also revealed evidence of its use in Roman times, including a burial surrounded by bricks in the right hand side of its atrium (as one enters) which remains unexcavated and in situ (Fernández Rodríguez et al. 2006, 97; Fernández Rodríguez and Romero Pérez 2007, 416). In addition, some grooves were identified in the first capstone of Viera that, in the excavators’ opinion, might have been caused by Roman quarrying, perhaps contributing to the partial dismantling of the monument (Fernández Rodríguez et al. 2006, 95).

How can this information on the use of the spaces surrounding Menga and Viera in Roman times be interpreted? First of all, it must be noted that just a short distance away (some 500m to the south-east) there is a Roman rural settlement known as Carnicería de los Moros (Ferrer Palma 1997a, 136; Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a, 184; Fernández Rodríguez and Romero Pérez 2007, 416). Remains of walls and a hydraulic structure with opus signinum that could have formed part of this rural settlement have been found near Viera. It seems possible that the Roman graves found around the perimeter of the dolmens could be connected with the inhabitants or occupiers of this suburban villa. The University of Málaga team dated these funerary contexts to between the late 5th and 6th centuries AD (Ferrer Palma 1997a, 136). They emphasised the fact that those buried had no grave goods, interpreting it to mean that the people buried there were low class, perhaps servants of the villa (Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a, 184).

Middle Ages

The excavations conducted in the atrium of Menga in the spring of 2005 revealed two human skeletons: the arrangement and context suggested that these burials were medieval (Navarrete Pendón 2005, 24–25) (Fig. 1.10). Both individuals were interred in simple, single graves in a prone position, with the upper and lower limbs extended, and hands at the pelvis. Neither individual was buried with any grave goods, nor was any type of funerary architecture found apart from the grave pit. Two subsequent radiocarbon dates demonstrate that those two individuals died between the 8th and 11th centuries AD (Díaz-Zorita Bonilla and García Sanjuán 2012, 244–245). Both bodies were approximately aligned with the axial symmetry of the dolmen (in other words, “in line” with the chamber), suggesting those who buried them wanted to place them in that exact position, acknowledging their awareness of the existence of the megalithic monument (and perhaps its great age).

Fig. 1.10: Excavation of medieval inhumation no.1 in the atrium at Menga (2005). Photo: Juan Moreno.

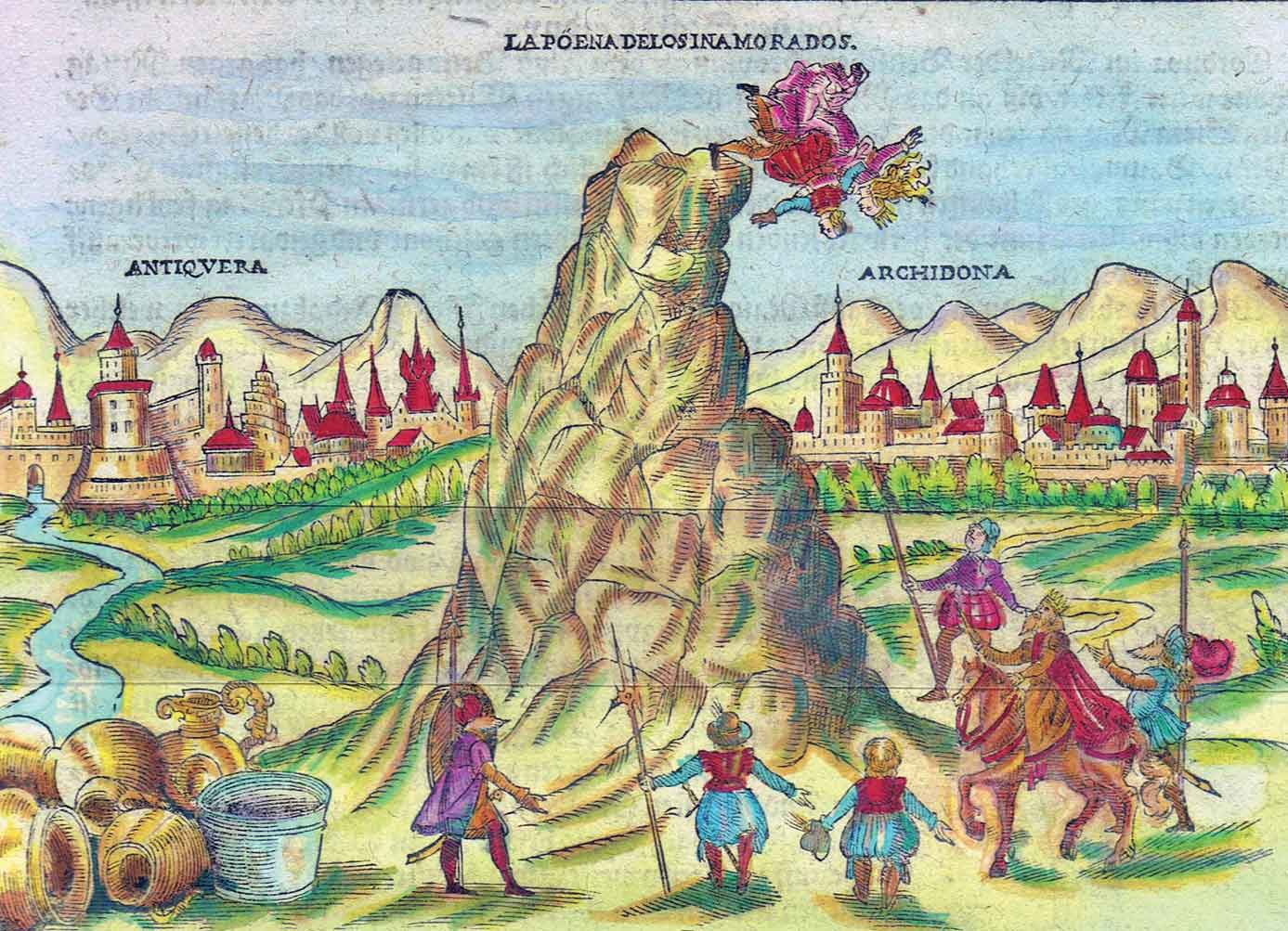

Fig. 1.11: Visualisation of the legend of La Peña de los Enamorados published in Basel in 1610 in Cosmographia Universalis (first edition 1507).

No other cases have been identified of megalithic sites (or prehistoric burial places in general) in the Antequera region being reused in the Middle Ages. The only other possible testimony is found in the schematic rock art complex of Peñas de Cabrera (Casabermeja, Málaga) located 30km south-east of Antequera. Engraved cruciform figures were found at this site, alongside an important series of schematic motifs, suggesting it was used as a sanctuary by Mozarab communities (Maura Mijares 2010, 119). The continuity of use of Peñas de Cabrera into the Middle Ages raises the question of the calvario (Christian cross) carved into the third orthostat of Menga (on the left as you enter). As noted by Bueno Ramírez et al. (forthcoming), this calvario was carved with a different technique from that used for the other motifs carved on that particular upright. Its specific chronology, however, remains a matter of conjecture.

The excavations carried out in the atrium of Menga in the spring of 2005 also discovered “medieval” pottery as well as “some resealed 8-maravedíes3 coins” (Navarrete Pendón 2005, 20–21). Similarly, Hispano-Muslim materials were recorded in Viera, inside the “tunnel” (considered to have been made by “plunderers”) located at the back of the passage’s orthostats, dated to the 14th and 15th centuries AD, coinciding with the Nasrid dynasty.

Modern and contemporary times

Menga appears to have played a sacred and/or funerary role as an ancestral site from its foundation up until some point in the late 1st or early 2nd millennium AD. This religious and/or funerary significance seems to decline with the abrupt cultural shift brought about by the Castilian conquest of the region between AD 1410 and 1462 and the subsequent Christianisation. However, there is consistent evidence that between the 16th and 18th centuries it was known and surrounded in a shroud of mystery and legend.

In 1587, the prebendary of Granada Cathedral, Agustín de Tejada Páez, wrote a manuscript entitled Discursos Históricos de Antequera. In an account of “some antiquities and curiosities” in his city, he referred to “a cave which is called Menga, and another besides which (not long ago) has been discovered, and they are on the outskirts of the city as you leave towards Granada”. Tejada Páez claimed that these “caves” (the second could be Viera) were “made by hand and must have been nocturnal temples where gentiles came at night to perform sacrifices”. In the late 16th century, therefore, there was a clear awareness of the existence and age of Menga (and most likely the Viera dolmen also), its construction and purpose attributed to non-Christian cults on whose behalf “sacrifices” were performed. In the mid-17th century, in his History of Antequera, Francisco de Tejada y Nava (nephew of Tejada Páez) considered Menga to be the “… work of supernatural beings in which men performed sacrifices or demonic rituals” (Sánchez-Cuenca López 2011, 15).

La Peña de los Enamorados was also famous in the 16th century AD as a “natural monument”, suggested by the fact that it features in an engraving in the German edition of the Universalis Cosmographia dated to 1610 (although first published in 1507), providing a pictorial version of the legend to which the mountain owes its name (Fig. 1.11). Different versions of this late medieval legend tell the story of a Muslim man and a Christian woman (or vice versa) who decide to run away together when their relationship is rejected by their families. They are chased as they try to escape and seek refuge on La Peña de los Enamorados but, cornered by their pursuers, they jump to their deaths off the north face precipice, where they are later buried (Jiménez Aguilera 2006).

It is likely that Menga was used as a refuge, dwelling, or even animal pen during these centuries. Many of the publications and reports consulted in writing this paper make reference to the existence of “modern” materials in the excavated zones of the interior and exterior areas of Menga although, once again, these materials have never been the subject of any detailed study. The geoarchaeological survey conducted by the University of Granada concluded that the visible wear on the lower third of several orthostats and (most notably) pillars was caused by animals rubbing against them, suggesting Menga was used as a stable at some point in its history (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006, 178). The two radiocarbon dates, obtained from animal bones found in the upper part of the shaft filling (Riquelme Cantal 2012, 232), fall between the late 17th and first half of the 20th century AD (Table 1.1).

Rafael Mitjana y Ardison stated that he first saw the “Cave of Mengal” on 17 April 1842, and that he visited the monument on 25 occasions between this date and the publication of his Memoria in 1847. He was aware of the scientific importance of the monument, which had never been recognised before, and so ordered that it be cleaned and the entrance closed off with a fence (Rodríguez Marín 2006, 124). If a fence was necessary, that implies that the site was known and frequented. Mitjana’s Memoria spread around the world very quickly: when British traveller Louisa Tenison travelled through southern Spain in 1852, she made her way to Antequera especially to visit the already famous megalithic monument of Menga (Tenison 1853). In early 1885, Alfonso XII, the King of Spain, was touring the province of Málaga visiting those affected by the serious earthquake that occurred on 25 December 1884: he also visited Menga. Impressed by the dolmen, he ordered that it be declared a National Monument: this came to pass on 1 June 1886, following the issuing of a Royal Order (Ruiz González 2009, 20). In 1896, Blanco y Negro magazine published the first photograph of Menga on its cover (taken by the photographer Juan Barrera) with the title “Old Spain”, commenting that “although the Cave of Menga was declared a national monument some years ago, nothing has been done to restore it and now it is in a complete state of abandonment” (Sánchez-Cuenca López 2011, 66). A watercolour included in a British publication of 1926 (the sixth edition of the 1906 book The Cities of Spain, by Alexander Wallace Rimington) depicts Menga as a picturesque traditional dwelling (Fig. 1.12). It is not known whether this watercolour was painted at the site, or if it is a fanciful recreation based on 19th-century clichés spread by European travellers about Spain and Andalusia.

Fig. 1.12: Watercolour by A. Wallace Rimington picturing Menga as a dwelling, published in Edward Hutton The Cities of Spain (Methuen & Co., London, 1906) Source: Archive Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera.

Fig. 1.13: Fired bullets discovered in Trench 21 of the University of Málaga 1991 excavations at Menga, currently held at the Málaga museum. Photo: Leonardo García Sanjuán.

There is one final episode in the biography of Menga that is worth mentioning. Both during the University of Malaga excavations, and during those of spring 2005, numerous bullets with clear signs of impact were identified (Fig. 1.13). Many of these fired bullets are held in the Málaga museum: in all likelihood they were left behind after summary executions performed after General Franco’s uprising against the Spanish Republic in July 1936. Their study may some day provide further details on what would appear to be the saddest episode in the millenary biography of Menga.

Corollary

Menga exemplifies a wider cultural phenomenon that is well documented throughout Iberia: namely the permanence and changing roles of megalithic monuments through later prehistory, Antiquity and the Middle Ages (García Sanjuán et al. 2007; 2008; García Sanjuán and Díaz-Guardamino 2015). Due to its ‘aura’ and exceptional material properties, namely its large scale and durability, Menga has been a constant feature in its surrounding landscape, acting as a focus for complex social interactions, and providing the arena for the negotiation of cultural traditions and identities.

Acknowledgements: We owe a debt of gratitude to several colleagues who generously provided us with invaluable unpublished data, and dedicate a special acknowledgement to all of them.

Notes

1 We refer to those carried out by the University of Málaga in 1986, 1988, 1991 and 1995 (Marqués Merelo et al. 2004a; Ferrer Palma, 1997a), the intervention carried out in 2005 to support the installation of a new electrical system (Navarrete Pendón, 2005), and those conducted subsequently between 2005 and 2006 by the University of Granada (Carrión Méndez et al. 2006a; 2006b).

2 This copper punch or awl is part of the small collection of objects from Viera held in the Málaga museum (Aranda Jiménez et al. 2013), and was already published in the summary of G. and V. Leisner (1943, pp. 182–185 and pl. 58). According to its shape, it can be dated to the Chalcolithic, which fits well with the set of materials that accompany it, especially the lithic materials. However, it is not possible to rule out an Early Bronze Age date, when this type of tool was very common and in which, as a C14 date has pointed out (Aranda Jiménez et al. 2013), Viera was also in use.

3 The maravedí coin was used between the 11th and 14th centuries AD.

References

Aranda Jiménez, G. 2013. Against uniformity cultural diversity: the ‘others’ in Argaric societies. In: Cruz Berrocal, M., García Sanjuán, L. and Gilman, A. (eds) The Prehistory of Iberia: debating early social stratification and the state. Routledge: New York, pp. 99–118.

Aranda Jiménez, G., García Sanjuán, L., Lozano Medina, A. and Costa Caramé, M. E. 2013. Nuevas dataciones radiométricas del dolmen de Viera (Antequera, Málaga). La Colección Gómez-Moreno. Menga. Journal of Andalusian Prehistory 4, pp. 235–248.

Bueno Ramírez, P., de Balbín Behrmann, R., Barroso Bermejo, R. and Vázquez Cuesta, A. forthcoming. Los símbolos de la muerte en los dólmenes antequeranos y sus referencias en el paisaje de la Prehistoria Reciente de Tierras de Antequera. In: García Sanjuán, L. (ed.) Antequera Milenaria. La Prehistoria de las Tierras de Antequera. Junta de Andalucía: Seville.

Cámalich Massieu, M. D., Martín Socas, D. and González Quintero, P. 2004. Conclusiones. In: Martín Socas, D., Cámalich Massieu, M. D. and González Quintero, P. (eds) La Cueva del Toro (Sierra del Torcal, Antequera, Málaga). Un Modelo de Ocupación Ganadera en el Territorio Andaluz entre el VI y II Milenios ANE. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 297–323.

Carrión Méndez, F., Muñiz López, T., García González, D., Lozano Rodríguez, J. A., Félix, P. and López Rodríguez, C. F. 2006a. Intervención en el Conjunto Megalítico de Menga y Viera (Antequera, Málaga). Unpublished Report. University of Granada: Granada.

Carrión Méndez, F., Lozano Rodríguez, J. A., García González, D., Muñiz López, T., Félix, P., Esquivel Guerrero, J. A. and Mellado García, I. 2006b. Estudio Geoarqueológico de los Sepulcros Megalíticos de Cueva de Menga y Viera y El Romeral (Antequera, Málaga). Unpublished Report. University of Granada: Granada.

Clavero Toledo, J. L. 2010. Investigación sísmica en simas de la alta Axarquía (Málaga): Comportamiento de la falla que originó el terremoto de 1884. Jábega 102, pp. 130–140.

Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, M. and García Sanjuán, L. 2012. Las inhumaciones medievales del atrio del dolmen de Menga (Antequera, Málaga): estudio antropológico y cronología absoluta. Menga. Journal of Andalusian Prehistory 3, pp. 237–250.

Fernández Rodríguez, L. E., Romero Pérez, M. and Ruiz de la Linde, R. 2006. Resultados preliminares del control arqueológico de los trabajos de consolidación del sepulcro megalítico de Viera, Antequera. Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía/2003, Tomo III. Actividades de Urgencia. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 89–99.

Fernández Rodríguez, L. E. and Romero Pérez, M. 2007. Las necrópolis en el entorno de Antikaria y Singilia Barba. Bases para su estudio sistemático. Mainake 29, pp. 401–432.

Fernández Ruiz, J. 2004. Uso de estructuras megalíticas por parte de grupos de la Edad del Bronce en el marco de Río Grande (Málaga). Mainake 26. Monográfico Los Enterramientos en la Península Ibérica durante la Prehistoria Reciente, pp. 273–229.

Fernández Ruiz, J., Marqués Merelo, I., Ferrer Palma, J. E. and Baldomero Navarro, A. 1997. Los enterramientos colectivos de El Tardón (Antequera, Málaga). In: de Balbín Berhmann, R. and Bueno Ramírez, P. (eds) Actas del II Congreso de Arqueología Peninsular (Zamora, Septiembre de 1996), Volume II. Fundación Rei Afonso Henriques: Zamora, pp. 371–380.

Ferrer Palma, J. E. 1997a. Proyecto de reconstrucción arquitectónica y paleoambiental en la necrópolis megalítica de Antequera (1985–1991): aspectos metodológicos. In: Martín Ruiz, J. M., Martín Ruiz, J. A. and Sánchez Bandera, P. J. (eds) Arqueología a la Carta. Relaciones entre Teoría y Método en la Práctica Arqueológica. Diputación Provincial de Málaga: Málaga, pp. 119–144.

Ferrer Palma, J. E. 1997b. La necrópolis megalítica de Antequera. Proceso de recuperación arqueológica de un paisaje holocénico en los alrededores de Antequera, Málaga. Baetica 19, pp. 351–370.

Ferrer Palma, J. E., Baldomero Navarro, A. and Garrido Luque, A. 1987a. El Cerro de Marimacho (Antequera, Málaga). Baetica 10, pp. 179–188.

Ferrer Palma, J. E., Fernández Ruiz, J. and Marqués Merelo, I. 1987b. Excavaciones en la necrópolis campaniforme de El Tardón (Antequera, Málaga), 1985. Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía/1985 III. Actuaciones de Urgencia. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 240–243.

Ferrer Palma, J. E., Marqués Merelo, I., Baldomero Navarro, A. and Aguado Mancha, T. 2004. Estructuras tumulares y procesos de construcción en los sepulcros megalíticos de la provincia de Málaga: la necrópolis megalítica de Antequera. Mainake 26. Monográfico Los Enterramientos en la Península Ibérica durante la Prehistoria Reciente, pp. 117–210.

García Sanjuán, L. and Wheatley, D. 2009. El marco territorial de los dólmenes de Antequera: valoración preliminar de las primeras investigaciones. En Ruiz González, B. (ed.) Dólmenes de Antequera. Tutela y Valorización Hoy. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 128–143.

García Sanjuán, L. and Wheatley, D. 2010. Natural substances, landscape forms, symbols and funerary monuments: elements of cultural memory among the Neolithic and Copper Age societies of Southern Spain. In: Lillios, K. and Tsamis, V. (eds.): Material Mnemonics. Everyday Memory in Prehistoric Europe. Oxbow Books: Oxford, pp. 10–39.

García Sanjuán, L. and Lozano Rodríguez, J. A. forthcoming. Menga: biografía de un monumento neolítico excepcional. In: García Sanjuán, L. (ed.) Antequera Milenaria. La Prehistoria de las Tierras de Antequera. Junta de Andalucía: Seville.

García Sanjuán, L. and Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, M. 2015. The outstanding biographies of prehistoric monuments in Iron Age, Roman and Medieval Iberia. In: Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, M., García Sanjuán, L. and Wheatley, D. (eds) The Lives of Prehistoric Monuments in Iron Age, Roman and Medieval Europe. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 183–204.

García Sanjuán, L., Garrido González, P. and Lozano Gómez, F. 2007. Las piedras de la memoria (II). El uso en época romana de espacios y monumentos sagrados prehistóricos del Sur de la Península Ibérica. Complutum 18, pp. 109–130.

García Sanjuán, L., Garrido González, P. and Lozano Gómez, F. 2008. The use of prehistoric ritual and funerary sites in Roman Spain: discussing tradition, memory and identity in Roman society. In: Fenwick, C., Wiggins, M. and Wythe, D. (eds) TRAC 2007. Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference (UCL and Birbeck College, University of London, 29 March–1 April 2007). Oxbow Books: Oxford, pp. 1–14.

García Sanjuán, L., Moreno Escobar, M. C., Márquez Pérez, J. and Wheatley, D. W. forthcoming. La Prehistoria Reciente de las Tierras de Antequera (VI–I milenios cal ANE): una perspectiva territorial. In: García Sanjuán, L. (ed.) Antequera Milenaria. La Prehistoria de las Tierras de Antequera. Junta de Andalucía: Seville.

García Sanjuán, L., Wheatley, D. W., and Costa Caramé, M. E. 2011a. The numerical chronology of the megalithic phenomenon in southern Spain: progress and problems. In: García Sanjuán, L., Scarre, C. and Wheatley, D. W. (eds) Exploring Time and Matter in Prehistoric Monuments: Absolute Chronology and Rare Rocks in European Megaliths. Proceedings of the 2nd European Megalithic Studies Group Meeting (Seville, Spain, November 2008). Menga: Journal of Andalusian Prehistory, Monograph 1. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 121–157.

García Sanjuán, L., Wheatley, D. W. and Costa Caramé, M. E. 2011b. Prospección de superficie en Antequera, Málaga: campaña de 2006. Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía/2006. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 3716–3737.

Hoskin, M. 2001. Tombs, Temples and Their Orientations: a new perspective on Mediterranean prehistory. Ocarina Books: Oxford.

Jiménez Aguilera, F. 2006. Archidona. La leyenda de la Peña de los Enamorados. Rayya. Revista Cultural de la Comarca Norte de Málaga 2, pp. 11–28.

Leisner, G. and Leisner, V. 1943. Die Megalithgräber der Iberischen Halbinsel. Der Süden. Römisch-Germanische Forschungen 1. Verlag Von Walter de Gruyter and Co: Berlin.

Leiva Riojano, J. A. and Ruiz González, B. 1977. Materiales arqueológicos del Cerro de Antequera. Jábega 19, pp. 15–18.

Lozano Rodríguez, J. A., Ruiz-Puertas, G., Hódar Correa, M., Pérez-Valera, F. and Morgado, A. 2014. Prehistoric engineering and astronomy of the great Menga Dolmen (Málaga, Spain): A geometric and geoarchaeological analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 41, pp. 759–771.

Marqués Merelo, I., Ferrer Palma, J. E., Aguado Mancha, T. and Baldomero Navarro, A. 2004a. La necrópolis megalítica de Antequera (Málaga): historiografía y actuaciones recientes. Baetica 26, pp. 173–190.

Marqués Merelo, I., Aguado Mancha, T., Baldomero Navarro, A. and Ferrer Palma, J. E. 2004b. Proyectos sobre la Edad del Cobre en Antequera, Málaga. Actas de los Simposios de Prehistoria de la Cueva de Nerja. La Problemática del Neolítico en Andalucía. Las Primeras Sociedades Metalúrgicas en Andalucía. Fundación Cueva de Nerja: Nerja, pp. 238–260.

Márquez Romero, J. E. 2009. Málaga. In: García Sanjuán, L. and Ruiz González, B. (eds) The Large Stones of Prehistory: megalithic sites and landscapes of Andalusia. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 198–227.

Márquez Romero, J. E. and Fernández Ruiz, J. 2009. The Dolmens of Antequera. Official Guide to the Archaeological Complex. Junta de Andalucía: Antequera.

Márquez Romero, J. E., Fernández Ruiz, J. and Rodríguez Vinceiro, F. 2009. Cronología del sepulcro megalítico del Tesorillo de la Llaná. In: Márquez Romero, J. E., Fernández Ruiz, J. and Mata Vivar, E. (eds) El Sepulcro Megalítico del Tesorillo de la Llaná, Alozaina (Málaga). Una Estructura Funeraria Singular en la Cuenca Media de Río Grande. University of Málaga: Málaga, pp. 81–88.

Maura Mijares, R. 2010. Guía del Enclave Arqueológico de Peñas de Cabrera. Junta de Andalucía: Seville.

Mergelina, C. de 1922. La necrópolis tartesia de Antequera. Actas y Memorias de la Sociedad Española de Antropología, Etnología y Prehistoria 1, pp. 37–90.

Mitjana y Ardison, R. 1847. Memoria sobre el Templo Druida Hallado en las Cercanías de la Ciudad de Antequera. Imprenta de José Martínez de Aguilar: Málaga.

Navarrete Pendón, V. 2005. Memoria de los Trabajos en el Control de Movimientos de Tierras para el Acondicionamiento de Iluminación y Accesos al Sepulcro Megalítico de Menga. Unpublished report.

Riquelme Cantal, J. A. 2012. Estudio de los restos óseos animales recuperados en la parte superior del relleno del pozo de Menga (Antequera, Málaga) en la intervención arqueológica de 2005. Menga. Journal of Andalusian Prehistory 3, pp. 221–236.

Rodríguez Marín, F. J. 2006. Rafael Mitjana y Ardison. Arquitecto Malagueño (1795–1849). Baetica 28, pp. 109–144.

Ruiz González, B. 2009. El proyecto de tutela y valorización de los dólmenes de Antequera. In: Ruiz González, B. (ed.) Dólmenes de Antequera. Tutela y Valorización Hoy. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, pp. 12–37.

Sánchez-Cuenca López, J. 2012. Menga in the Nineteenth Century: ‘The Most Beautiful and Perfect of the Known Dolmens’. Menga: Journal of Andalusian Prehistory Monograph 2. Junta de Andalucía: Seville.

Tenison, L. 1853: Castile and Andalucia. Richard Bentley: London.

Walker, M. J. 1995. El sureste, Micenas y Wessex. La cuestión de los adornos óseos de vara y puño. Verdolay 7, pp. 117–125.