Dolmens without mounds in Denmark

Abstract

The earliest monumental structures in Denmark appear at about 3700 BC, a couple of centuries after the first traces of a Neolithic economy in Denmark. The structures consist of elongated fenced areas, usually with or without timber built cists, but occasionally with stone built cists, such as in Barkær. These cists are the forerunners for the real dolmen-chambers, the latter built from erratic boulders and dating back to c. 3500 BC. This article uses examples from investigations of scheduled dolmens to show that originally the dolmen chambers were exposed, regardless of whether the chamber was free-standing, enclosed by a circle of stones (round dolmen), or had a rectangular setting of stones (long dolmen). Some dolmens were altered – often in multiple stages – in very dynamic ways, including the addition of extensive mound fill. Generally speaking however, many dolmens – especially later ones like Poskær Stenhus and the round dolmen at Tustrup – largely kept their original appearance. After around three centuries, at 3200 BC, the building of dolmens ceased, and instead a totally new type of monument – the mound-covered passage tomb – took over.

Keywords: dolmen, Denmark, free-standing chamber, multiperiod monuments, stone cist, barkærfeature

Poskær Stenhus – a key site

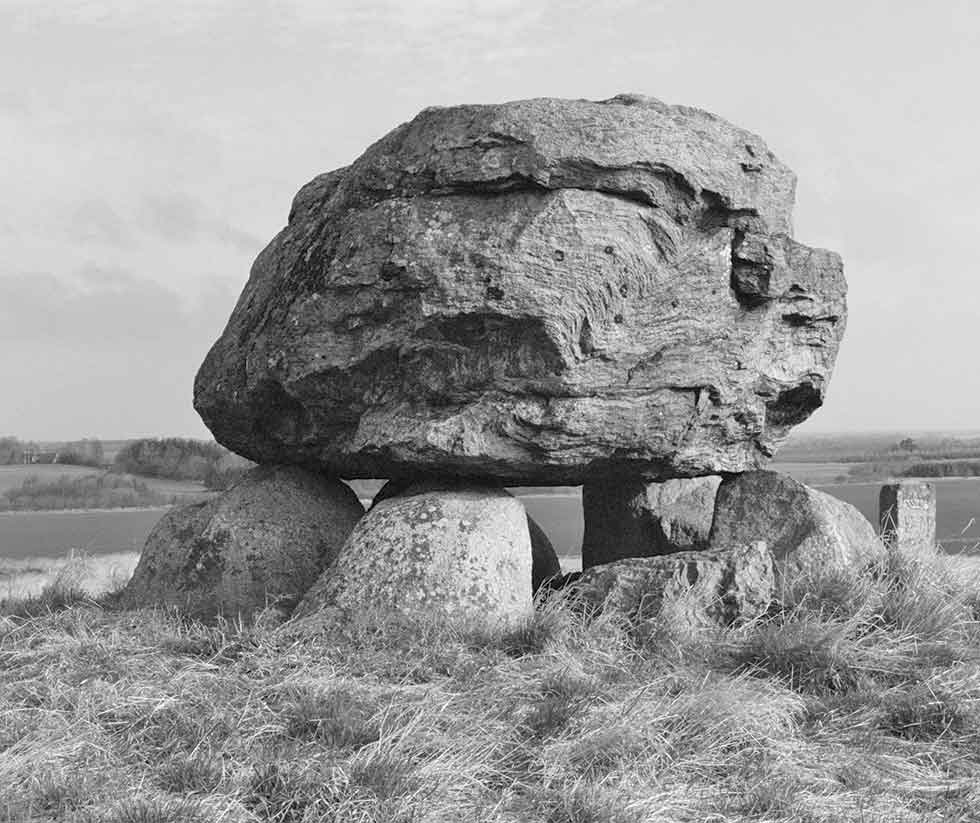

Since the middle of the first half of the 19th century, Danish dolmens have been national icons, depicted by painters in monumental and dramatic ways showing raised capstones against a blue sky. The earliest legal protection of selected dolmens dates back to the same time. One example is the famous round dolmen, Poskær Stenhus (Stenhus meaning stone house) in Eastern Jutland. It measures 15.5m in diameter and has one polygonal chamber; it was scheduled in 1860 (Eriksen 1999) (Fig. 8.1). Poskær Stenhus is a key site in the discussion of whether dolmens had mounds. Poskær Stenhus, like many of our dolmens, is an open structure with no sign of ever having had a mound cover. The visibility of its big stones was even more striking and monumental before 1943, when the bottom section of the façade of the kerbstones was covered up with earth to protect them from falling. In spite of its present appearance, Poskær Stenhus is believed by some archaeologists to be a ruined and skeletal megalithic structure, whose mound has disappeared through a combination of human action and natural erosion. A similar opinion is expressed on the 20-year-old information board at the site (removed in 2003) which, beneath a drawing of a mound hiding the chamber of Poskær Stenhus (Fig. 8.2), states the following (our translation):

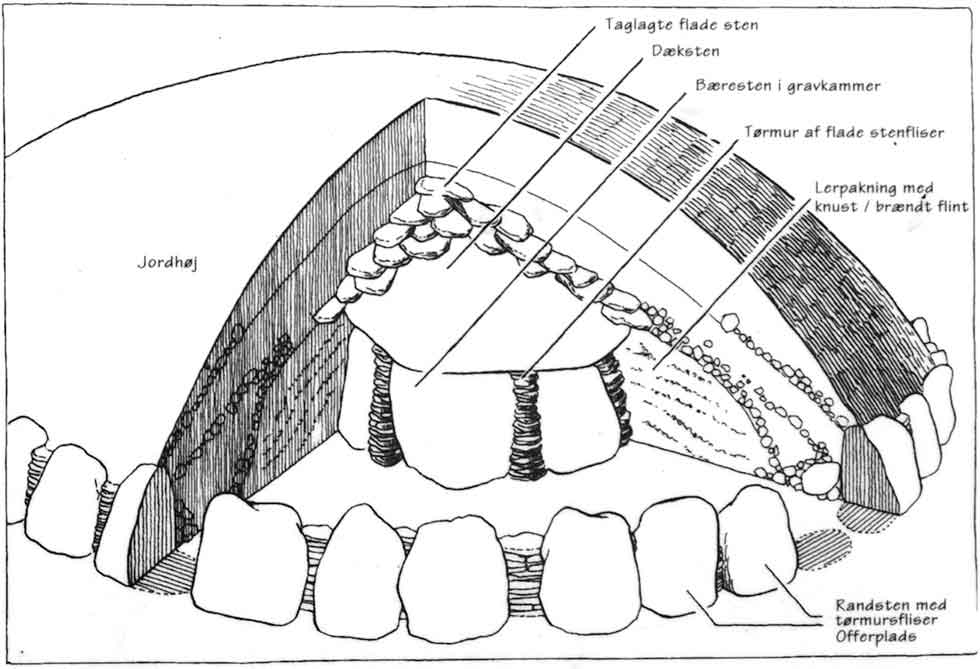

Reconstruction of the round dolmen’s original appearance before the destruction of the dry walls between the kerbstones and the removal of the soil of the mound, which perhaps concealed the chamber totally. The chamber was not – as it is today – open and accessible, but must have been opened up in connection with new burials and offerings to the dead and the gods.

Fig. 8.1: The round dolmen Poskær Stenhus, Mols, in Eastern Jutland. (Photo: P. Eriksen)

Fig. 8.2: Reconstruction drawing from the old information board at Poskær Stenhus, illustrating the original appearance of the site proposed by some archaeologists

A survey of Poskær Stenhus, in 1995, demonstrated that this interpretation could not explain a number of construction details of the monument. Since then, the authors have conducted a study of dolmens with and without mounds (Eriksen and Andersen 2014). In this article we only deal with scheduled dolmens, but the book also includes information from the excavations of destroyed dolmens in the Sarup area, with many examples of dolmens originally without mounds.

Simple typology, definition and dating

In Denmark, all dolmens and the later passage tombs were built of stones left on the surface after the withdrawal of the ice. The main difference in morphology between dolmens and passage tombs is that the latter always have a passage connecting the interior of the chamber with the exterior of the mound, while dolmens never have a passage leading to the kerbstones or mound exterior.

Broadly speaking, the dolmens consist of two groups: an older group with small, mainly rectangular chambers, and a younger group with polygonal chambers which are generally bigger and higher than the chambers in the older group (see Figs 8.12 and 8.13). Usually dolmens have only one capstone, while passage tombs have more. Some passage tombs with a rounded floor plan are, in a misleading way, called great-dolmens (stordysser in Danish, Ebbesen 1979; Grossdolmen in German, Schuldt 1972). About 2400 protected megaliths (1800 dolmens and 600 passage tombs) are found in Denmark.

The mounds are built of earth, sometimes with intermittent layers of stones. They are not just mounds in the traditional sense, as the prehistoric layers comprising them can be divided into four principal classes: packing, cultic, natural, and real mound fill, the latter in the traditional sense of increasing the mound and sealing the structures inside it. The mound can be extremely low, or no traces of mound fill are found at all: the mound can also be extremely high. The shapes of the mounds vary from long rectangular, sometimes vaguely trapezoidal (long dolmens) to round (round dolmens). Finally, in the case of the free-standing dolmens, no mound is found at all.

The Neolithic period in Denmark begins around 3950 BC. The first monuments built there, at around 3700 BC, were elongated structures, frequently with imposing wooden constructions in one of the gables. We have called the whole structure a barkærfeature. After this monumental beginning, stone built cists and/or long barrows – which sometime cover the above-mentioned elongated structures with timber – were succeeded by dolmens at around 3500 BC, and by passage tombs at around 3200 BC.

Literature about Danish dolmens in foreign languages is sparse, but two books with summaries in English have been published recently (Ebbesen 2007; 2011).

Looking different – why?

The 1800 protected dolmens have very different appearances, spanning ruins with a few stones, free-standing chambers, and chambers in long or round mounds. These have levels of mound fill that vary from none to a complete cover of the chamber. Many of the monuments have been plundered for stones: the capstones are often missing, or several, if not all, of the kerbstones have been removed. Some of the remaining stones might have been broken or blown up into smaller pieces.

Until 1984, most Danish archaeologists believed that the dolmens, especially the later dolmens, were open structures in the Neolithic just like they appear today, but that year the erosion theory was put forward (Thorsen 1984). The idea – that man had a destructive, altering impact on the megaliths, combined with natural erosion – was not unknown, but with this theory every monument could fit into one and the same scheme in a very convincing way (Fig. 8.3).

The erosion theory operates at four stages, each illustrated by a section through the chamber in a long dolmen. Stage 1 is the newly built monument just as it was finished in the Neolithic. The mound completely covers the chamber in a gable roof shape, leaving only the upper top of the capstone visible. The long dolmen for the dead was meant to imitate a Neolithic house for the living. Some hundred years later in the Neolithic – in stage 2 – natural erosion has eroded the top of the mound, resulting in an exposed capstone but with kerbstones still almost completely hidden by the eroding mound fill. Stage 3 represents modern times (20th century) with more extensive farming activities: the eroded soil along the kerbstones is ploughed away or removed so the dolmen now looks like a dolmen without a mound. By stage 4 – in 1984 – the rest of the mound has disappeared together with the kerbstones; only the chamber survives, now as a freestanding structure. If this trend continued, the next stage would have been the removal of the capstone and later the orthostats of the chamber. However, in 1937, between stages 3 and 4, such monuments became protected by law.

Fig. 8.3: The Erosion Theory. (From S. Thorsen 1984)

The erosion theory convinced many Danish archaeologists that, originally, megalithic monuments in general were covered by a mound. The reconstruction in 1994 of the round dolmen at Tustrup in Eastern Jutland is an example of a monument that has been restored according to how a dolmen probably looked in the Stone Age, and this opinion is still maintained by the archaeologist who carried out the restoration (Dehn 2013; Hansen 2009a; 2009b; 2010). This theory is based upon the assumption that monuments such as the dolmens are single-period monuments. Of course, its supporters acknowledge that some dolmens have a more complicated building history; for example, that long dolmens grew longer as a result of additions (Kaul 2012).

In contrast to the erosion theory, we offer another explanation for the different appearance of the dolmens. Almost all dolmens are multi-period structures that evolved and changed their appearance in often very dynamic sequences – except the free-standing chamber, which marks the beginning of a possible sequence. The long barrow Bygholm Nørremark, in Eastern Jutland, serves as a good example (Rønne 1979; Mohen 1989, 97). The investigation of this monument was carried out in 1976–77 by Preben Rønne. It showed a monument built in four or five main phases, beginning with a 60m long timber enclosure that was covered by a long barrow, which was later elongated and surrounded by kerbstones. In the final stage, a passage tomb was inserted in the barrow, now 75m long, and an outer row of free-standing orthostats was added. Together, the phases span over 500-600 years; if we were to freeze the monument in each phase, we would have five different monuments. Dolmens could have developed in a similar multistage fashion (Holst 2006).

Some dolmens without mounds

The free-standing chambers make up a quarter of protected dolmens in Denmark. We know from older descriptions that many of them originally belonged to round or long dolmens with a higher or lower mound surrounded by kerbstones. Some of the free-standing chambers we see today, where no knowledge exists about their surrounding mounds, could also have appeared in this manner in the Neolithic. The only way to find out is by investigation. The first example of such an investigation is from Sweden, all the others are from Denmark.

The dolmen of Trollasten, situated in Scania, is a polygonal chamber, which was investigated in 1965 by Märta Strömberg (1968). The free-standing chamber was surrounded by pavings of smaller stones (Fig. 8.4). When we use the terms “pavement” or “paving” we do not mean carefully placed stones in the modern sense of the words. The stones are often placed quite arbitrarily and seem to reflect different activities and episodes, and appear to have accumulated over time in relation to different activities. One of the pavements – which Strömberg called the tablet – was very carefully executed. On the pavement in front of the dolmen lay potsherds and small clusters of burnt human bone, indicating that this surface was an activity area in the Neolithic. No traces of a mound or kerbstones were found.

Fig. 8.4: Free-standing chamber at Trollasten, Scania, surrounded by pavements, as revealed by the excavation in 1965. (Photo from Strömberg 1968)

Fig. 8.5: (above) 1879 plan of the round dolmen at Kjallesten, Lolland, with two circles of stones, the outer one being kerbstones; (below) 1999 section drawing: note animal activity is responsible for the mound to the right of the chamber. (Plan by Magnus Petersen, Nationalmuseet, section by N. H. Andersen and P. Eriksen)

In Denmark, there are only two examples of scheduled free-standing dolmen chambers where the surroundings have also been investigated: Lunden on the island of Langeland with a chamber of earlier or “older” type; and Ormslev in Eastern Jutland with a chamber of later or “younger” type. The excavations, by Jørgen Skaarup in 1974 and Torsten Madsen in 1975 respectively, showed similar pavements and that these chambers also had never been covered with mounds or surrounded by kerbstones (Skaarup 1985, 212–214; Nielsen 2003). Another example is the free-standing dolmen chamber at Tustrup, excavated by Poul Kjærum in 1955–56. This dolmen, a different monument from the round dolmen at the same site, has a chamber of ‘younger’ type that was a chamber without a mound in the Neolithic, just as it appears today. At that time, the chamber was surrounded by a pavement and a circular setting of small kerbstones, as well as an outer concentric circle of free-standing orthostats with a diameter of 11m (Eriksen and Andersen 2014, 194–203). The outer circle may be a later addition, perhaps in response to Beaker influence in the late Neolithic.

Fig. 8.6: Engraving of the long dolmen at Gunderslevholm Skov, Zealand, with surface of low inner mound covered by a scatter of stones. (From Madsen 1868)

Fig. 8.7. Polygonal chamber at Stenhus, Eastern Jutland, situated on top of a small hill. (Photo: P. Eriksen)

Kjallesten, on the island of Lolland, is a polygonal chamber in a round dolmen with small kerbstones. When it was recorded in 1879, another circle of smaller stones was visible at the surface between the chamber and the kerbstones, and it was noted that “only very little mound fill is seen in relation to the surrounding surface”. In 1999 we recorded a section through the monument to demonstrate the low surface of the mound in relation to the chamber (Fig. 8.5). Poskær Stenhus also had an inner circle of smaller stones but they were removed, possibly in 1859, the year before the monument was protected. Other chambers of ‘older’ types include Hydeskov Fredskov and Syllinge Skov (skov means forest), situated in Lolland and Southern Zealand respectively. These have inner stone circles, surrounded by smaller rectangular, nearly quadratic, settings of kerbstones, and are situated on completely flat terrain. They are good examples of spaces between kerbstones and chambers that, in prehistory, were sealed by smaller stone circles. These circles must not be confused with those of the kerbstones. A relevant parallel to these four dolmens with inner stone circles are the Irish dolmens at Carrowmore, where excavations in 1977–79 by Göran Burenhult revealed that they also lacked mounds (Burenhult 1980; Bergh 1995).

At Gunderslevholm Skov, in Zealand, we have a well preserved, 55m long dolmen with a chamber of ‘older’ type (Fig. 8.6). The monument is unique in Denmark because a scattering of 40–90cm big stones covers the interior surface inside the kerb without any intervening soil. The tops of the stones, which are some distance from the chamber, are quite low at around 1m when compared to the height of intact kerbstones and the top of the orthostats of the chamber. Similar to the inner stone circles just mentioned, this cover of scattered stones at the dolmen of Gunderslevholm Skov marks the last visible activity, irrespective of whether the stones were placed in the Neolithic or later. If a mound had covered the stones and it was later removed, traces should have been left, such as soil between the stones, or cleaved stones in the interior. That is not the case.

The normal settings of Danish dolmens and passage tombs in the landscape are on low-lying terrain or terraces. Settings on hilltops are unusual but do occur. The Stenhus dolmen – only 6km from Poskær Stenhus – is one such exception (Fig. 8.7). The first description of Stenhus, in 1878, mentions a mound, about 12m in diameter and 1m high, surrounding the chamber. No kerbstones could be detected. In a later description from 1925, 14 small-kerbstones, 75cm in size, were recorded. The monument was protected in 1925, and no alterations have taken place since the first description, except that the grass is higher nowadays. Unfortunately the vegetation hides the smaller stones that helped determine the diameter of the mound. These stones probably edged a pavement around the chamber. The fact that the chamber is placed on top of a small hill surrounded by the pavement – an original surface of the monument – makes it very unlikely that a covering mound ever hid the chamber. Just to cover the lower edge of the capstone, the mound inside the kerbstones should have been 1m higher at the chamber. The distance from the kerbstones to the outer edge of the chamber is only 3.5m.

Fig. 8.8: Round dolmen at Tustrup, Eastern Jutland, showing the lower layer of stones. Excavation demonstrated that the low mound consisted of two layers of stones separated by a layer of eolian sand. The capstone is missing. (Photo: P. Kjærum)

Fig. 8.9: Excavated section at the round dolmen at Tustrup, Eastern Jutland, between chamber to the right and kerbstone to the left. Note the two layers of stones separated by a layer of eolian sand. (Photo: P. Kjærum)

Fig. 8.10: Excavated section at the round dolmen at Tustrup, Eastern Jutland, with fallen kerbstones. Note the two layers of stones separated by a layer of eolian sand; the capstone is missing. (Photo: P. Kjærum)

Fig. 8.11: Polygonal dolmen chamber on hill of Rungeløsebjerg, Zealand, with impressive capstone. (Photo: P. Eriksen)

In 1956, Poul Kjærum excavated the previously mentioned round dolmen at Tustrup. The kerbstones formed a circle nearly 9m in diameter around the polygonal chamber. The mound fill consisted of two different layers of stones separated by a layer of eolian sand (Figs 8.8–8.10). According to Kjærum, the Neolithic surface of the area between the chamber and the kerbstones appears to be the lower stone layer. The totally level surface surrounding the monument lay in heath before the monument was scheduled in 1887, and remains there still. The absence of a thick layer of eroded mound fill on this surface also argues against a mound.

One of the main objections to the interpretation of the Tustrup round dolmen as a monument without a mound is the presence of large amounts of flagstones from collapsed dry walls between the kerbstones. So many flagstones are present that the top of the erected dry walls may have been on a level with the top of the kerbstones. We agree that the dry walls might have achieved this height, but we do not agree with the conclusion that such high dry walls demanded a mound of similar height to support them (Dehn 2013). Instead we – like the excavator Poul Kjærum – understand the dry walls and the kerbstones as forming a circular enclosure around the free-standing chamber. This enclosure was not built for eternity: some parts might have collapsed already in the Neolithic. Deliberate destruction and natural collapse were integrated and not unusual phenomena related to Neolithic monuments. They should be seen as similar to the burning down of timber cult houses, the filling of the long ditches of the Sarup enclosures with soil, and the smashing of ceramics and burning of flint artefacts in front of passage tombs.

An additional argument supporting the idea that some dolmens lacked mounds is the fact that many exposed capstones at Danish dolmens are of such grandeur, and made of such spectacular material, that it must have been the intention of the dolmen builders that these magnificent stones should be visible, eye-catching and monumental (Fig. 8.11). This appearance is quite similar to that of portal dolmens in Britain and Ireland, where “the capstones float to the sky” (Whittle 2004). The capstones of Danish dolmens are often much thicker and heavier than those of British and Irish portal dolmens, but the same concept may apply to them too.

Fig. 8.12: The “older” or earlier type of dolmen chamber: access would have been impossible had they been covered by mounds. Passages orthostats are low and small and constitute only symbolic expressions of a passage. (From A.P. Madsen 1868)

Fig. 8.13: The later or “younger” type of dolmen chamber: access would have been impossible had they been covered by mounds. The passage orthostats are small, and effectively present only a symbolic passage. (From Madsen 1868)

A final argument for dolmens without mounds is the rudimentary character of their passage. The passage is built from one, or occasionally two, pairs of smaller stones: these are often quite low compared with the orthostats of the chambers (Figs 8.12 and 8.13). Capstones over these symbolic passages are missing, and there is no evidence that they ever existed. The length of dolmen passages is always too short to reach the exterior of a possible mound. Taken together with the low height of the passage, this would make it impossible to enter the chamber through the passage if a mound covered the chamber. This assumes there is a passage at all: at the Tustrup round dolmen there is none in front of the opening to the chamber.

Fig. 8.14: Long barrow at Kellerød, Zealand, showing the unusually tall mound. With a height of 1.5m, the mound exceeds the height of the kerbstones and also covered the capstone of the single stone-built chamber (a dolmen cist). (Photo: P. Eriksen)

Dolmens with mounds – a lot of mounds!

Many long dolmens with dolmen chambers of the ‘older’ type have considerable mound fill. The height of the mounds might reach to the lower edge of the capstones, but there can also be so much mound fill that the capstones cannot be seen. How is this to be explained?

Let us first look at the chambers that, including the capstone, are completely enclosed by a mound. A good example is the only chamber in the 125m long, 7.5m broad, and 1.5m high dolmen at Kellerød at Zealand, which is surrounded by kerbstones (Fig. 8.14). The longitudinal chamber is situated near one of the ends of the long dolmen. It was discovered and excavated in 1933 (Nielsen 1984; Ebbesen 2008, 358–360). The chamber measured 2.5m x 0.6–0.75m and was only 60cm high. It was constructed of equally high stones, two at each long side and one at each gable, and covered by one capstone 3m long, 1.6m broad, and 0.35–0.5m thick. Like the capstone, the six side stones were all very thin, around 10–40cm, and with parallel sides. The stones were more like slabs than ordinary boulders, and the chamber was more like a cist than a normal dolmen chamber.

A similar stone cist, built of slabs in the same manner as the one at Kellerød, was found in one of the two long barrows at Barkær in Eastern Jutland, investigated by P. V. Glob in 1946–49 (Liversage 1992). The chamber measured 2.0m x 0.6m, and was 60–70cm high: it was covered by a thin slablike capstone, which again had been sealed by half a meter of mound fill. In the same long barrow, traces were found of a cist made of wooden planks. At the other long barrow at Barkær, two similar timber cists were discovered. The two long barrows, which are around 90m long and 6.5–7.5m wide, are placed 10m apart and parallel to each other. In fact these barrows with no kerbstones should be classified as long barrows, predating the long dolmens with ordinary dolmen chambers of the ‘older’ type. The stone cist and the three timber graves at Barkær are regarded as contemporary, and the stone cist is just a wooden chamber translated into stone (Liversage 1992).

These two examples – Barkær and Kellerød – of stone cists made of slabs including their capstones, might be termed dolmen cists. They should not be confused with the ‘younger’ ordinary dolmens with chambers of ‘older’ types, built of much thicker erratic boulders with plain surfaces turned towards the interior of the chamber. The long barrows with the dolmen cists should be considered part of the tradition of early Neolithic long barrows. Many of these were perhaps closed by mounds and turned into memorials in the same manner as Neolithic long barrows in Brittany about one thousand years before (Scarre 2014, 2016).

Dolmens and passage tombs are like day and night

Although we are aware that some passage tombs might originally have been free-standing, like the Irish Mound of the Hostages at Tara (O’Sullivan 2005), we assume that – in general – they were covered by mounds. Standing outside the mound of a passage tomb, only the entrance to the passage would be visible, as opposed to dolmens, where all the stones can easily be seen. In lectures, the Danish archaeologist Professor Peter Vilhelm Glob has expressed the difference in this way: a dolmen had to be seen from the outside, a passage tomb from the inside (pers. comm.).

The same difference prevailed in the Neolithic. At the dolmens, the rituals could be followed by a number of people, while only a few people could observe and participate in the rituals inside the passage tombs. Dolmens and passage tombs represent two different cases, both cultic and architectural, where the architecture was dictated by the cult. Alongside the construction of the passage tombs, it is most likely that older monuments were refashioned according to the new customs by adding more soil to their mounds.

Both dolmens and passage tombs must not be understood as burial chambers in the traditional sense. In some dolmen cists, old investigations have produced perhaps a single skeleton, such as the one at Kellerød (Nielsen 1984; Ebbesen 2008, 358–360). However, no evidence of complete skeletons contemporary with the first use of these megaliths has yet been found from the real dolmens and the passage tombs. The fragmented skeletons found at the megalithic tombs form part of complicated rituals that also took place at other structures, such as the ceremonial enclosures and natural sites, where complete or partial skeletons were deposited (Andersen 2000).

Fig. 8.15: Artificial dolmen erected as a war memorial in Haderslev in 1927 in honour of the Danish citizens of the town killed in the First World War in German service. (Photo: P. Eriksen)

In summary, the forerunners for the real dolmens were the dolmen cists in the long barrows, the barkærfeatures. At the beginning the cists were exposed, but later – perhaps very soon after – they were covered with large amounts of mound fill. The oldest real dolmens followed this tradition in part, but the capstones were visible in the round or long mounds. At the same time, free-standing chambers, with or without kerbstones, appeared and – with the arrival of the ‘younger’ dolmen chamber – became the dominant type of monument.

All in all, there is no reason to doubt or alter the common and popular understanding of how dolmens, particularly the more recent ones, looked in the past and still look today (Fig. 8.15).

Note: This broad outline is further explained and documented elsewhere (Eriksen and Andersen 2014).

References

Andersen, N. H. 2000. Kult og ritualer i den ældre bondestenalder. Kuml 2000, pp. 13–57.

Bergh, S. 1995. Landscape of the Monuments: a study of the passage tombs in the Cúil Irra region. Riksantikvarieämbetet: Stockholm.

Burenhult, G. 1980. The Archaeological Excavation at Carrowmore, Co. Sligo, Ireland. Excavation seasons 1977-79. Institute of Archaeology at the University of Stockholm, Theses and papers in North-European Archaeology 9, G. Burenhults Förlag: Stockholm

Dehn, T. 2013. “Open dolmens” – a matter of decay. In: Bakker, J. A., Bloo, S. B. C. and Dütting, M. K. (eds) From Funeral Monuments to Household Pottery. BAR S2474. Archaeopress: Oxford, pp. 95–109.

Ebbesen, K. 1979. Stordyssen i Vedsted. Studier over tragtbægerkulturen i Sønderjylland. Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology University of Copenhagen, Arkæologiske Studier 6. Akademisk Forlag: Copenhagen.

Ebbesen, K. 2007. Danske dysser. Danish Dolmens. Attika: Copenhagen.

Ebbesen, K. 2008. Danske jættestuer. Attika: Copenhagen.

Ebbesen, K. 2011. Danmarks megalitgrave. Attika: Copenhagen.

Eriksen, P. 1999: Poskær Stenhus – Myter og virkelighed. Moesgård Museum: Aarhus.

Eriksen, P. and Andersen, N. H. 2014. Stendysser. Arkitektur og funktion. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab: Aarhus.

Hansen, S. 2009a. Dysser i høj – Grundtvigs offersted. Fund og Fortid. Arkæologi for alle 4, pp. 4–7.

Hansen, S. 2009b. Dyssen i Gunderslevholm Skov. Årsskrift. Fuglebjergegnens Lokalhistoriske Forening – Borupris’ Venner, pp. 4–9.

Hansen, S. 2010. Dysserne ved Strids Mølle. Dysser i høje, del 2. Fund og Fortid. Arkæologi for alle 1, pp. 12–15.

Holst, M. K. 2006. Tårup. A round dolmen and its secondary burials. Journal of Danish Archaeology 14, pp. 1–21.

Kaul, F. 2012. Multi-period construction of megalithic tombs – and the megalithic tombs in Shetland. In: Mahler, D. L. (ed.) The Border of Farming and the Cultural Markers. Nationalmuseet: Copenhagen, pp. 100–121.

Liversage, D. 1992. Barkær. Long Barrows and Settlements. Institute of Prehistoric and Classical Archaeology University of Copenhagen, Arkæologiske Studier 9, Akademisk Forlag: København.

Madsen, A. P. 1868: Afbildninger af danske Oldsager og Mindesmærker. Thieles Bogtrykkeri: Copenhagen

Mohen, J.-P. 1989. The World of Megaliths. Cassell: London.

Nielsen, N. 2003. Ormslev-dyssen – en dysse uden høj? Fritstående dysser i tragtbægerkulturen. Kuml 2003, pp. 125–156.

Nielsen, P. O. 1984. Flint axes and megaliths – the time and context of the early dolmens in Denmark. In: Burenhult, G. (ed.) The Archaeology of Carrowmore. Theses and Papers in North-European Archaeology 14. Riksantikvarieämbetet: Stockholm, pp. 376–387.

O’Sullivan, M. 2005. Duma na nGiall. The Mound of the Hostages, Tara. Bray: Wordwell.

Rønne, P. 1979. Høj over høj. Skalk 1979(5), pp. 3–8.

Scarre, C. 2014. Dysser uden høje i Storbritannien, Frankrig og Irland. In: Eriksen, P. and Andersen, N. H. 2014. Stendysser. Arkitektur og funktion. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab: Aarhus, pp. 216–236.

Scarre, C. 2016. Accident or design? Chambers, cairns and funerary practices in Neolithic western Europe. In: Laporte, L. and Scarre, C. (eds) The Megalithic Architectures of Europe. Oxbow Books: Oxford, pp. 69-78.

Schuldt, E. 1972. Die mecklenburgischen Megalithgräber. Museum für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Schwerin: Berlin.

Skaarup, J. 1985. Yngre stenalder på øerne syd for Fyn. Rudkøbing: Langelands Museum.

Strömberg, M. 1968. Der Dolmen Trollasten in St. Köpinge, Schonen. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia 7. Gleerup: Lund.

Thorsen, S. 1984. Dysserne. Kæmpers værk. Nedrige altre. Oldheltenes grave. Arkæologiens smertensbørn. Eller de dødes huse? In: Bolvig, A., Mahler, D. and Holtegaard, G. (eds) Fortid og Nutid. Søllerød Kommune: Søllerød, pp. 29–38.

Whittle, A. 2004. Stones that float to the sky: portal dolmens and their landscapes of memory and myth. In: Cummings, V. and Fowler, C. (eds) The Neolithic of the Irish Sea. Materiality and Traditions of Practice. Oxbow Books: Oxford, pp. 81–90.