Decorative techniques in Breton megalithic tombs (France): the role of paintings

Abstract

The decoration of megalithic monuments is one of the ritual actions that define the spaces that were dedicated to the ancestors. Consideration of the artistic programmes employed during the construction of megalithic tombs provides parameters for analysis that support the search for the ideology and symbolic meaning of these monuments. Most of the known megalithic art within the Atlantic region has already been recorded, and this has shown that carvings are the commonest form. However, studies and analysis carried out in the Iberian Peninsula during recent years prove that paintings must have had a greater presence than was initially thought. By applying methodologies similar to those developed elsewhere in Europe, important new evidence could be recovered. In this paper we propose a programme of research for the megalithic monuments of Brittany.

Keywords: Megalithic monuments, megalithic art, carved motifs, painted motifs, ritual, chaîne opératoire

The importance of megalithic art

The use of painted, carved, or sculpted decorations in European funerary practice makes megalithic art a basic reference point for analysing the use of burial spaces. Decorating megalithic monuments was one of the ritual actions that defined the spaces that were dedicated to the ancestors. Engravings, paintings, and sculptures should therefore be included in any analysis of the process of building megalithic tombs. The addition of decoration was part of a deliberate programme, and hence represents an organised discourse.

Fig. 19.1: Brittany showing location of sites mentioned in the text

Standardisation of the codes relating to location and the association of images guaranteed a widespread understanding amongst ancient viewers (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 1994; 2004). These signs were not merely practical: they were used to transmit messages along with the ideology of the Western European megalith builders (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 2002). Consideration of such artistic schemes within megalithic construction would provide additional parameters for analysis to support the search for the ideology and symbolic meaning of monuments. The integration of these programmes into the study of the ideological and physical configuration of ancestral burial places is a challenge currently facing investigative research into European megaliths.

The majority of the known megalithic decoration within the Atlantic region is carved (Shee Twohig 1981). However, recent studies in the Iberian Peninsula prove that paintings had a greater presence than was initially thought (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 1992; 2002; 2006; Bueno Ramírez et al. 2004a; Carrera 2011). By applying methodologies developed in other European contexts (such as the Iberian Peninsula) to new areas, elements can be added that are vital for a thorough understanding of this interregional tradition.

Although there was long-lasting association between engravings and paintings, there are many monuments that have only painted motifs, for example in the Iberian Peninsula (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2009) and in the South of France, e.g. the Courion dolmen (Gutherz et al. 1998). However some raw materials, especially limestone and some granites, preserve paintings better than others, leading to differential survival.

In order to apply the methodologies developed in the Iberian Peninsula, a group of decorated and engraved megaliths was identified in Brittany. The Breton region was chosen for several reasons. It was found to be exceptional in terms of the presence of painting on megalith supports. Further, some of the decorative and other evidence connect the Iberian Peninsula with Brittany, a connection that is reinforced by new chronologies from the Iberian Peninsula that are closer to those from Brittany than previously expected (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2007; Furholt and Müller 2011). Brittany is also a region of special significance in the relationship between megalithic art and cultural elements such as menhirs, jade axes, and decorated ceramics (Calado 2002; Herbaut and Querré 2004; Laporte and Le Roux 2004; Pétrequin et al. 2012; Shee Twohig 1981).

Choosing the sites

Monuments that are considered to be of the appropriate period (Barnenez, Tumulus de Mont-Saint-Michel (TMSM), Petit Mont, and Goërem at Gâvres) were selected to reflect the development of Breton megalithic construction. Barnenez is a representative case, particularly chamber H, which is one of the most completely decorated monuments in Brittany (described by Giot (1987) (Fig. 19.1). The chamber was sealed following the excavations, ensuring excellent preservation when compared to other dolmens.

These monuments provide a good representation of the thematic repertoire present within Breton art, which includes geometrical motifs such as zigzags, simple or complex circles, rectangles in different stages of elaboration, and concentric series of curved lines, sometimes with a straight edge. These were accompanied by axes, crooks, and occasionally more elaborate elements such as bows. In more recent periods, anthropomorphic representations appear, such as the Pierres Plates type idols, or breasts and necklaces (Shee Twohig 1981, 54). It is a simple repertoire, but it relates to other Atlantic megalithic art and has some interesting nuances. The anthropomorphic images show an especial singularity. This is the case not only in the older forms as the buckler and écusson, but also in the later examples.

Some geometric motifs reproduce isolated shapes found in other monuments, such as U-shapes with outcurved ends, interpreted as birds or boats (Cassen 2011). Sometimes this type of engraved decoration is associated with paintings (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2012). This link points to the possibility that the carved motifs were completed using other, less visible, techniques. The interpretation of these motifs should consider the possibility of more complex original compositions than those we can see nowadays (Le Quellec 2006).

What to do and how to do it

Throughout over 20 years of experience in working with Iberian dolmens we have developed a documentation methodology. This methodology is based on complementary systems for the documentation of Paleolithic art (Bueno Ramírez et al. 1998; 2009b; Balbín Behrmann et al. 2012). It includes not only a thorough analysis of the decorated surfaces, but also integrates information regarding their spatial arrangement. In the Iberian Peninsula there is an interesting relationship between painted and engraved open-air art, and funerary art that is displayed on the walls of dolmens and funerary caves, created using the same techniques (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 2000; Bueno Ramírez et al. 2004b). Important methods of rock art analysis have also been developed in the British Isles and northern Europe (Bradley 2009). Unfortunately, this type of interpretation is rarely employed in fieldwork in France and Italy. At present, funerary structures are still analysed separately from those associated with everyday life. However, the work of D’Anna and his team should be noted, as they connect funerary images with similar symbols within territories that were marked and travelled through by the same groups (D’Anna et al. 2006). Likewise, research by Hameau links pigments from funerary caves with pigments from other non-funerary decorated contexts (Hameau et al. 2001).

Fig. 19.2: Diagram in “artistic” style of the stela of Oles (Asturias, Spain). (From Bueno Ramírez et al. 2007)

A detailed study of the artistic scheme of individual monuments is part of the micro-level of our protocol. Each orthostat is studied as a panel, as it is physically delimited from the other supports. In order to observe the decoration, it is vital to have adequate illumination and to know how to position it. White, frontal light is the best option. Pigments are photographed using all available traditional and digital resources. The camera used is capable of capturing infra-red light (1) and digital filtering packages such as Photofilter, Photofilter 1.0 manual use and Tiffen are also used. In addition we apply analogical Tiffen, Heliopan, and Kodak Wratten gelatin filters and B+W. Previous experience has been important, enabling easier identification of the most effective methodologies. When evidence was found for the possible presence of pigments, a microphotography device was used. This provides 300x magnification with its own internal illumination (Lumos X-Loupe – G Model) allowing us to distinguish pigment particles, their colour and even the remains of the tool used to apply them. Brush strokes, for example, were documented at the Soto dolmen in Huelva.

Each panel (or orthostat) is described to aid the analysis of the spatial analysis of the monument. The dolmens display a compact artistic discourse. However, today we know that individual blocks were often taken from other, older, monuments and were then manipulated by repainting, reengraving, or fragmentation in order to create new monuments (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2007). Detailed interpretation of the decoration of the stones is fundamental for reconstructing the history of the artistic discourse on the walls of the monument. Repainting, for example, demnonstrates complex sequences of re-use during the use of a monument. In some Iberian examples, it has been possible to date individual phases of painting (Carrera and Fábregas 2002; Steelman et al.2005).

Every photograph taken of each orthostat adds information. Various software applications such as Adobe Photoshop and Corel Photo Paint are used to highlight or contrast the tones of the pigment or surface. Image J is used to separate warm and cold ranges with a false colourization that allows one to distinguish lost or poorly visible tones. Together these are used to make a digital representation: at no point is a direct tracing made from the walls (Balbín Behrmann et al. 2012).

The final model combines different systems of graphic expression. In our opinion the most useful are those that include surface characteristics, such as the quality and depth of engravings, and evidence of technical and thematic superimpositions, since this builds upon the available information. It can be “artistic”, or it can be simple (Fig. 19.2).

Other teams prefer to offer more synthetic visions using coloured schemes. These do allow easy identification of the position and interrelationships of the images but they do not explain the techniques nor do they capture the characteristics of the stone surface (Fig. 19.3). They are very useful when explaining the difficulties of interpreting Paleolithic art to the public. However, models are scientific interpretations and should offer tools for distinguishing the techniques used. We have chosen this method to publish our work at Barnenez chamber H (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2015). We regard this as the penultimate phase before final documentation (Fig. 19.4).

Prehistoric painting is most commonly identified though photography: megalithic art is no exception. Many sites are justifiably described as megaliths with paintings. However, some professionals, including ourselves, have chosen to sample the pigments to authenticate the information, and to provide further detail for the study of the operational sequences through which the construction of the monument occurred. In addition, analysis of organic pigments offers the possibility of direct chronology (Carrera et al. 2005).

3D-scanning and photogrammetry provide geo-referenced information about the orthostats, precisely situating the decorative motifs. It is easier to locate the motifs of a megalithic monument than those in a cave. However, a 3D scanner does not provide clear images of the paintings: a specialized team must always have studied them beforehand. Ideally there should be closer cooperation between professionals working with three-dimensional techniques and archaeologists who specialize in rock art. We have used such methods to record the Andalusian megaliths (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2013a), and they have also been employed in Brittany (Cassen 2011).

Fig. 19.3: Colour coding showing phases of Paleolithic art in the Côa valley, Portugal. (From Baptista 1999)

Although it is the role of the paintings that is emphasised here, the variety of carved components must not be forgotten, including occasional sculptures, engravings, and the different techniques used complete and enrich the standard themes. We recommend a holistic analysis using specific methodologies for the detection of paintings. This is the only way to study thoroughly the complex funerary schemes in which diverse techniques and themes come together. Their combination represents the materialization of an ideological system that was of great importance throughout Western Europe (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 2002).

Fig. 19.4: Preliminary survey of paintings and engravings in the dolmen de Menga at Antequera (Málaga, Spain). (From Bueno Ramírez et al. 2013)

Preliminary results (Table 19.1)

Photographic analysis

We have carried out an initial photographic evaluation in all of the selected monuments using the methodology described above. This has provided indications of pigmented areas on several orthostats. There is black painting in chamber H at Barnenez, at Gâvres, and in the TMSM. Red paint is found in chamber H at Barnenez, in chamber E of the TMSM and probably also on dolmen 2 at Petit Mont. Black and red occur together in two monuments. The application of artificial colours was primarily used for geometric motifs. These include zigzags and rectangles with rounded edges, horizontal zigzags, and vertical zigzags. The painting follows a previously defined line and was probably made with a thick brush. This is especially visible in the black painting of orthostat C at Barnenez. Occasionally, paint has been used to extend and complete engravings: this is visible in the axe on menhir D in Barnenez chamber H (Fig. 19.5).

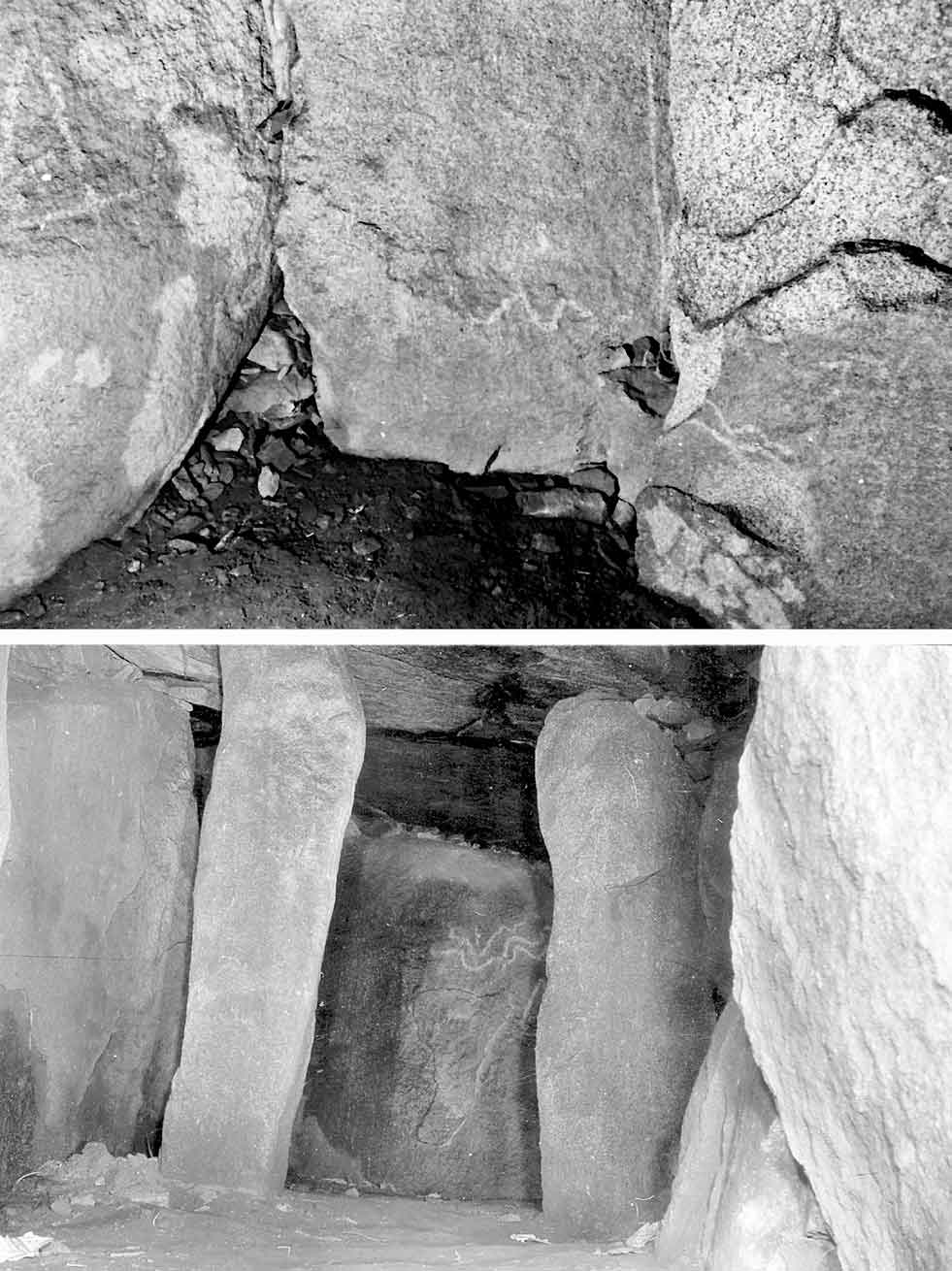

Fig. 19.5: (above) Menhir at the entrance to Barnenez chamber H: a hafted axe is highlighted by black paint and the upper part of the stone is finished in the shape of a glans penis; (below) entrance to the chamber with backstone beyond

Table 19.1. Themes and techniques in the decorated megalithic tombs of Brittany

Engravings also play an important rôle. Paintings and engravings are used alongside sculpture in chamber H at Barnenez, and at Petit Mont and Gâvres. There appear to have been regional schemes in Brittany requiring different techniques for the complex decoration of specific monuments.

Pigment analysis

Three methods of analysis have been employed to study the pigments used to produce these painted motifs: direct sampling, Raman spectroscopy, and fluorescent lighting. Each has advantages and disadvantages. The first offers more convincing results but damages the stones (although leaving no visible mark: the sample measures only 1 mm2); the latter two are non-destructive. Raman spectroscopy allows the identification of organic matter, which cannot be detected using fluorescent lighting. In some cases this is sufficient but the interpretation of samples can be problematic. Where there are thick surface crusts or where the stone contains high amounts of clay or chalk, the fluorescence can be affected. At present, direct samples have been taken only from chamber H at Barnenez and from Gâvres (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2012; 2015).

Conservation issues

Paint does not preserve well and it has been demonstrated that white and black, in that order, are especially delicate (Carrera 2011, 496). Another facet of the project has therefore sought to incorporate and analyse older archival documentation from all of the monuments within this study. This has yielded spectacular results in the case of Barnenez. The photographs taken when chamber H was first discovered show black paint in the chamber and more red paint than remains today (Fig. 19.6). Information provided by original photographic negatives is therefore very important: it may even allow us to propose a more complete reconstruction of the decoration. The search continues for older documentation for TMSM and Petit Mont.

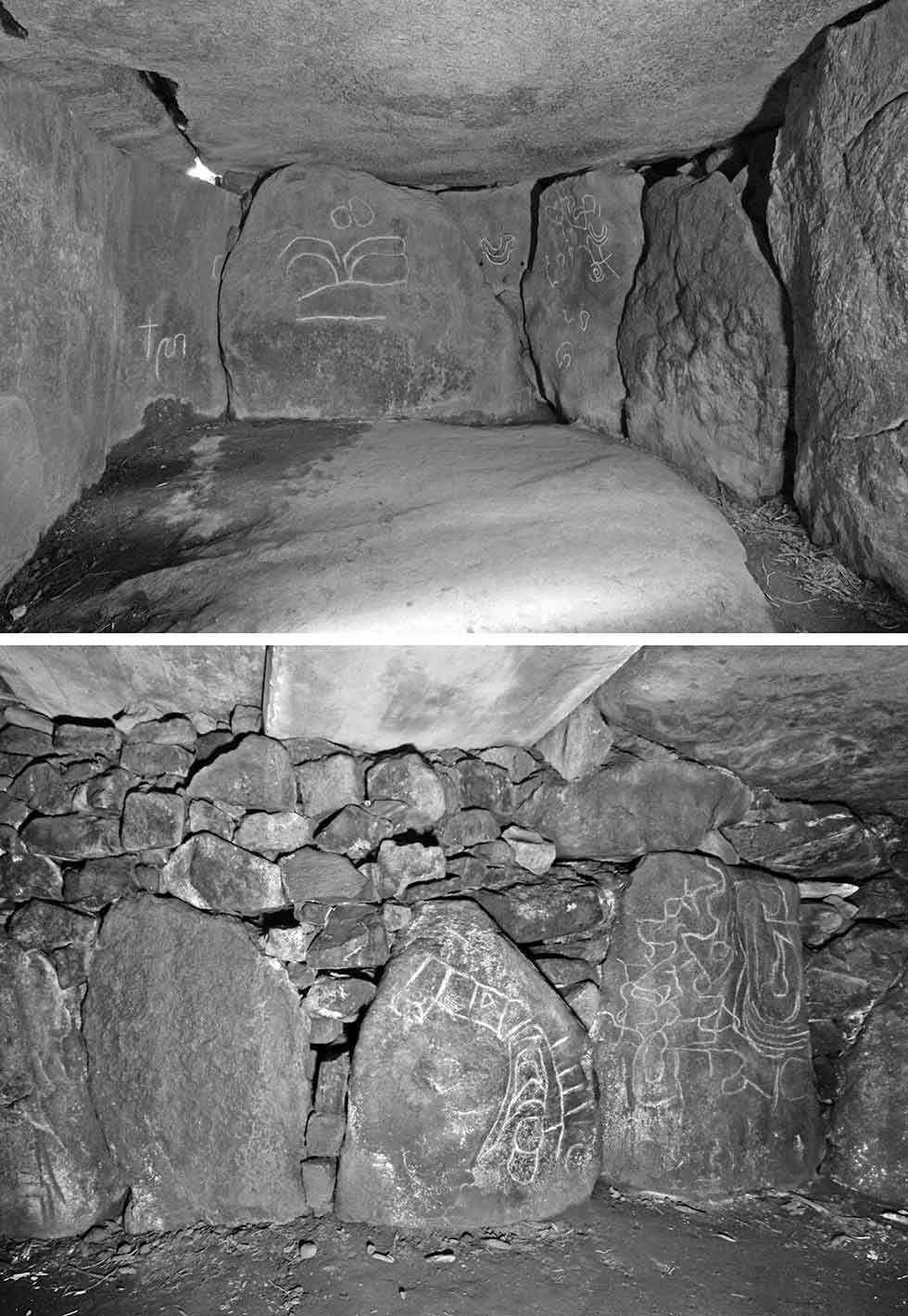

For this type of cultural heritage, conservation is a significant challenge. It is a particular issue in the Carnac area where most megalithic monuments are open to the public without any control. Cases such as Mané Kerioned or Mané Lud are shocking. The motifs within these megalithic tombs have been painted, infilled and reworked several times, mostly by vandals, destroying their archaeological value. It is of some concern that monuments of such significance for our understanding of the past are being “devoured” by poorly controlled tourism–although there are exceptions (Fig. 19.7). Our project therefore contains another vital element: to rescue information that will disappear if the management of these monuments does not focus more strongly on control of visitor access. Older repairs and restorations have also left their mark.

Fig. 19.6: Black paintings visible in photographs taken shortly after the discovery of Barnenez chamber H in the 1960s: (above) detail of the orthostats on the northern side of the chamber; (below) view of the backstone with remains of black painting on the left

Future plans

The encouraging results from chamber H at Barnenez justify the use of similar methodologies in all of the Breton megaliths. Our initial results already open up wider issues. The rectangular motifs in black pigment that were found on orthostat A of dolmen H at Barnenez are very similar to the engraving on a reused support in chamber J of the same mound. Some Breton motifs can be paralleled in other regions of France, especially around Paris, as L’Helgouach noted (1986). The best example is the decoration of the dolmen du Berceau at Saint-Piat (Renaud and Jagu 1994; Jagu et al. 1998). Écusson (shield) idols, hafted axes, and a bow, all made by piqueté (pecking) technique, are linked by thick carved angular strokes on the frontal slab of the chamber. This suggests the possibility of reuse or of a remodelling of the chamber during which the engravings were added (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2007). The deliberate choice of red stone for the construction of the chamber also deserves further study (Fig. 19.8).

Fig. 19.7: Mané Lud (above) and (below) Mané Kerioned

There is evidence of the role of the colour black elsewhere in France, in the black pigment used in the Marne hypogea (Villes 1997) and in the Courion dolmen mentioned above. As in Brittany, painted and engraved motifs can be contrasted. This is confirmed by the recording project we have initiated with Rémi Martineau at some of the Marne hypogea. The situation is analogous to that in the Iberian Peninsula: painting or engraving techniques enhance the visibility and expressiveness of some motifs. These designs, however, may be applied using either of the techniques, or both at the same time.

L’Helgouach (1970, 255) pointed out the clear relationship between engravings of Pierres Plates type and the stelae from Provence. Further support for this relationship hs being discovered through recent study of some of the painted stelae (Maillé 2010).

Fig. 19.8: Engraved motifs in the dolmen du Berceau at Saint-Piat (Eure-et-Loire, France)

Other evidence suggests relationships on an even larger scale. In addition to painting, there are techniques such as the superficial piqueté (pecking) found at Barnenez and other Breton monuments. This is frequently encountered in Iberian monuments. There is also evidence that specific motifs, such as hafted axes, were repeated. Moreover, false low-relief techniques are used in both regions to make deep, angular stroke engravings that clearly demarcate certain areas. Usually these are painted. Both aspects, motifs and techniques, are evident in Andalusian monuments (Bueno Ramírez et al. 2013b; in press) (Fig. 19.9).

Fig. 19.9: Pecked axes in the dolmen of Alberite II (Cádiz, Spain). (From Bueno Ramírez et al. 2007)

Fig. 19.10: (above left) Decorated orthostat at Gavrinis (Brittany); (above right) carved motifs at Montefrio dolmen 29 (Granada, Spain); (below left): chamber doorway of the dolmen de la Viera at Antequera (Málaga, Spain) with (below right) detail of the red painting

The use of such techniques at Gavrinis indicates that the engravings there could have been painted; that possibility requires investigation. (Fig. 19.10). We are not seeking to list all possible parallels; Le Quellec (2006) has previously noted the futility of that kind of interpretation. However, we believe that the symbolic relationships correspond to shared cultural mechanisms that explain the presence of certain prestige goods in both the Iberian Peninsula and Brittany.

The analysis is by no means complete, and there is still scope for further work. For example, sampling in the British Isles, and especially at sites on the Orkney Islands, could add valuable information (Darvill and Andrews 2014). As we proposed some time ago (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 2002), Atlantic megalithic art demonstrate the existence of a funerary code that was widely spread across Europe. Its variability parallels that found in funerary architecture. However, everything points to systems of interaction where painting and engraving techniques are evidence of common ideological content. Therefore, the use of specific protocols and methodologies that are dedicated to the documentation of painting must be a research objective for Atlantic megalithic studies. Only in this way can we interpret the true extent of this technique in Brittany, and in the rest of Europe.

Acknowledgements

This study has been made possible thanks to the project “The colours of death”, financed by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competividad, and the “Barnenez, Plouezoc’h, Finistère” project, supported by the Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles de Bretagne. We collaborated with colleagues who were involved in the original research on these monuments: Charles-Tanguy Le Roux, Michel Le Goffic, and Joël Le Cornec; and are also grateful for the help of Richard Longuepée and the commune of Saint-Piat in our study of the dolmen du Berceau. Rémi Martineau has generously allowed us to review the evidence of painting in the Champagne hypogea. Many other colleagues have also assisted us, especially Roger Joussaume, Jean-Marc Large, Emmanuel Mens, Gérard Bénéteau, Laure Salanova, Alain Villes, Nuria Sanz, Denis Vialou and Jean-Pierre Mohen. The necessary permits for this work were issued by the Direction Générale des Antiquités de Bretagne directed by Stéphane Deschamps. A. Belaud de Sauce has been a constant help.

The translation from the original Spanish was undertaken by J. Verdonkschot.

References

Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Bueno Ramírez, P. and Alcolea, J. 2012. Técnicas, estilo y cronología en el arte paleolítico del sur de Europa: cuevas y aire libre. In: Sanches, M. de J. (ed.) Artes Rupestres da Pré-História e da Proto-História: Paradigmas e Metodologias de Registo. Trabalhos de Arqueología 54. Direçao-Geral do Patrimonio Cultural: Lisboa, pp. 105–124.

Baptista, A. M. 1999. No tempo seu tempo. A arte dos caçadores paleolíticos do Vale do Côa. Centro Nacional de Arte rupestre: Vila Nova de Foz Côa.

Bradley, R. 2009. Image and Audience: Rethinking Prehistoric Art. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann, R. de. 1992. L’Art mégalithique dans la Péninsule Ibérique. Une vue d’ensemble. L’Anthropologie 96, pp. 499–572.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann, R. de. 1994. Estatuas-menhir y estelas antropomorfas en megalitos ibéricos. Una hipótesis de interpretación del espacio funerario. Homenaje a González Echegaray. Museo y Centro de Investigación de Altamira: Santander, pp. 337–347.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann, R. de. 2000. Art mégalithique et art en plein air. Approches de la définition du territoire pour les groupes producteurs de la péninsule ibérique. L’Anthropologie 104, pp. 427–458.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann, R. de. 2002. L’Art mégalithique péninsulaire et l’Art mégalithique de la façade atlantique: un modèle de capillarité appliqué à l’Art post-paléolithique européen. L’Anthropologie 106, pp. 603–646.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann, R. de. 2004. Imágenes antropomorfas al interior de los megalitos: las representaciones escultóricas. In: Calado, M. (ed.) Sinais de pedra. I Coloquio Internacional sobre Megalitismo e Arte Rupestre. Fundação Eugénio de Almeida: Evora. CD.

Bueno Ramírez, P. and Balbín Behrmann. R. de. 2006. Arte megalítico en la Península Ibérica: contextos materiales y simbólicos para el arte esquemático. In: Martínez, J. and Hernández, M. (eds) Arte rupestre Esquemático en la Península Ibérica. Comarca de Los Vélez: Almería, pp. 57–84.

Bueno, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2004a. Arte Megalítico en Andalucía: una propuesta para su valoración global en el ámbito de las grafías de los conjuntos productores del Sur de Europa. Mainake XXVI, pp. 29–62.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2004b. Application d’une méthode d’analyse du territoire à partir de la situation des marqueurs graphiques à l’interieur de la Péninsule Ibérique: le Tage International. L’Anthropologie 108, pp. 653–710.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2007. Chronologie de l’art mégalithique ibérique: C14 et contextes archéologiques. L’Anthropologie 111, pp. 590–654.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2009a. Pintura megalítica en Andalucía. Estudios de Prehistoria y Arqueología. Homenaje a Pilar Acosta. Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, pp. 141–170.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2009b. Análisis de las grafías megalíticas de los dólmenes de Antequera y su entorno. In Dólmenes de Antequera: tutela y valorización hoy. Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico: Sevilla, pp. 186–197.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de and Barroso, R. 2013a. Símbolos para los vivos, símbolos para los muertos. Arte megalítico en Andalucía. In: Martínez García, J. (ed.) Arte Esquemático. Actas del II Congreso de Los Velez. Grupo de Desarrollo Rural de los Vélez: Almería, pp. 25–48.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Barroso, R., Carrera, F. and Ayora, C. 2013b. Secuencias de arquitecturas y símbolos en el dolmen de Viera, Málaga. Menga 4, pp. 249–264.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Barroso, R. and Vázquez, A. in press. Los símbolos de la muerte en los dólmenes antequeranos y sus referencias en el paisaje de la Prehistoria Reciente de Tierras de Antequera. Antequera milenaria: Antequera

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R., de, Laporte, L., Gouézin, P., Cousseau, F., Barroso, R., Hernanz, A., Iriarte, M. and Quesnel, L. 2015. Natural colours/artificial colours. The case of Brittany’s megaliths. Antiquity 89, pp. 55-71.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Díaz-Andreu, M. and Aldecoa, A. 1998. Espacio habitacional/espacio gráfico: grabados al aire libre en término de la Hinojosa (Cuenca). Trabajos de Prehistoria 55, pp. 101–120.

Bueno Ramírez, P., Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Laporte., L, Gouézin, P., Barroso, R., Hernanz, A., Gavira-Vallejo, J. M. and Iriarte, M. 2012. Paintings in Atlantic Megalithic Art: Barnenez. Trabajos de Prehistoria 69, pp. 123–132.

Calado, M. 2002. Standing stones and natural outcrops. In Scarre, C. (ed.) Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europe. Perception and Society during the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. Routledge: London, pp. 17–35.

Carrera, F. 2011. El arte parietal en monumentos megalíticos del Noroeste ibérico. Valoración, diagnosis y conservación. BAR S2190, Archaeopress: Oxford

Carrera, F. and Fábregas, R. 2002. Datación radiocarbónica de pinturas megalíticas del Noroeste peninsular. Trabajos de Prehistoria 59, pp. 157–166.

Carrera, F., Fábregas, R., Bello, J. M., Balbín Behrmann, R. de, Bueno Ramírez, P., Ayora, C., Carrera, J., Lloret, A., Suriol, J., García, A., Silva, B., Rivas, T. and Prieto, B. 2005. Procedimiento interdisciplinar de caracterización, diagnosis y preservación de pintura megalítica. Actas de II Congreso del GEIIC “Investigación en Conservación y Restauración”. Grupo español del IIC: Barcelona, pp. 259–267.

Cassen, S. 2011. Le Mané Lud en mouvement. Déroulé des signes dans un ouvrage néolithique de pierres dressées à Locmariaquer (Morbihan). Préhistoires Méditerranéenes 2, pp. 11–70.

D’Anna, A., Guendon, J. L., Pinet, L. and Tramoni, P. 2006. Espaces, territoires et mégalithes: le plateau de Cauria (Sartène, Corse-du-Sud) au néolithique et l’âge du bronze. In Duhamel, P. (dir.) Impacts interculturels au Néolithique moyen. Du terroir au territoire: sociétés et espaces. Revue Archéologique de l’Est, supplément 25, Société Archéologique de l’Est: Dijon, pp, 191–213.

Darvill, T. and Andrews, K. 2014. Polychrome Pottery from the later Neolithic of the Isle of Man. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 243, pp. 531-541

Furholt, J. and Muller, J. 2011. The earliest monuments in Europe – architecture and social structures (5000–3000 cal. BC). In: Furholt, M., Lüth, F. and Müller, J. (eds) Megaliths and Identity: early monuments and Neolithic societies from the Atlantic to the Baltic. Rudolf Habelt: Bonn, pp. 15–31.

Giot, P. R. 1987. Barnenez, Carn, Guennoc. Travaux du laboratoire “Anthropologie-Préhistoire-Protohistoire-Quaternaire armoricains”: Rennes.

Gutherz, X., Jallot, L. and Garnier, N. 1998. Le monument de Courion (Collias. Gard) et les statues-menhirs de l’Uzege méridionale. Archéologie en Languedoc 22, pp. 119–134.

Hameau, Ph., Cruz, V., Laval, E., Menu, M. and Vignaud, C. 2001. Analyse de la peinture de quelques sites postglaciares de Sud-Est de la France. L’Anthropologie 105, pp. 611–626.

Herbaut, F. and Querré, G. 2004. La parure néolithique en variscite dans le sud de l’Armorique. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 101, pp. 497–520.

Jagu, D., Blum B. and Mourain, J. M. 1998. Dolmens et menhirs de Changé à Saint-Piat (Eure-et-Loir). Témoins archéologiques des rites et pratiques funéraires des premiers agriculteurs beaucerons. ARCHEA: L’Eure et Loir.

Laporte, L. and Le Roux, C. T. 2004. Bâtisseurs du Néolithique, Mégalithisme de la France de l’Ouest. Maison des Roches: Paris.

L’Helgouach, J. 1970. Le monument mégalithique du Goërem à Gâvres (Morbihan). Gallia Préhistoire 13, pp. 217–261.

L’Helgouach, J. 1986. Les sépultures mégalithiques du Néolithique final: 1es architectures et figurations pariétales. Comparaisons et relations entre massif armoricain et nord de la France. Revue Archéologique de l’Ouest Supplément 1, pp. 189–194.

Le Quellec, J. L. 2006. L’art mégalithique en France: récents développements. In Joussaume, R., Laporte, L. and Scarre, C. (eds) Origine et développement du mégalithisme de l’ouest de l’Europe. Conseil Général des Deux-Sèvres: Bougon, pp. 689–719.

Maillé, M. 2010. Hommes et femmes de pierre. Statues-menhirs du Rouergue et du Haut Languedoc. Archives d’écologie préhistorique: Toulouse.

Pétrequin, P., Cassen, S., Errera, M., Klassen, L., Sheridan, A. and Pétrequin, A. M. (eds). 2012. Jade. Grandes haches alpines du Néolithique européen, Ve au IVe millénaires av. J.-C. Les Cahiers de la MSHE Ledoux 17. Presses Universitaires de Franche-Comté: Besançon.

Renaud, J. and Jagu, D. 1994. Une datation concernant le site mégalithique de Changé à Saint-Piat obtenue grâce aux collections du Muséum de Chartres. Bulletin de la Société des Amis de Musée de Chartres 14, pp. 2–4.

Shee Twohig, E. 1981. The Megalithic Art of Western Europe. Clarendon Press: Oxford.

Steelman, K. L., Carrera, F., Fábregas, R., Guiderson, T. and Rowe, M. W. 2005. Direct radiocarbon dating of megalithic paints from north-west Iberia. Antiquity 79, pp. 379–389.

Villes, A. 1997. Les figurations dans les sépultures collectives néolithiques de la Marne, dans le contexte du Bassin parisien. Brigantium 10, pp. 148–177.