JIM AND GEORGE DEFEND DEMOCRACY

One night in October of 2023, I had a strange dream. All I knew was that it involved vodka and cigarettes and my dad with a gun.

When I woke up, I pieced the shards of the dream together into a memory of a real story that my late father, Jim Alter, liked to tell. During World War II, Dad flew thirty-one harrowing missions over Nazi-occupied Europe in a B-24 Liberator. As a navigator/bombardier, he handled a device called the Norden bombsight, a primitive computer that was supposed to help bombardiers lock on to targets. Dad told me that it didn’t work well when an airplane was in the clouds. Slight detail.

Dad had orders to destroy the classified Norden bombsight if he and his crew were captured. On one of his last missions, the B-24 came under heavy German fire and made an emergency landing in Hungary. Dad emptied his Colt .45 into the bombsight and crawled out of the plane with his hands up. Fortunately, he and the crew were greeted by friendly Soviet troops. After a night of drinking, Dad ripped a page from a log and scrawled out a contract: the Russians could keep the unflyable airplane in exchange for vodka, cigarettes, and safe passage back to the American base in Italy.

First Lieutenant James Alter, Army Air Corps

Three years earlier, Dad was a sophomore at Purdue when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He liked college, was in love (not with Mom yet), and had what he then would have called a “swell” new convertible. Leaving all that was hard. There is no right time in anyone’s life to do what you can to help defend democracy. But he did. He enlisted.

When he got home to Chicago in 1945, Dad learned from my great-grandmother that he had bombed the town in Hungary where she said “our people” were from, though by that time almost any Jewish relatives in the area who hadn’t emigrated to America had been carted away to the camps.

Dad had no regrets. He was part of what Tom Brokaw dubbed “the Greatest Generation.” The men and women who survived the Great Depression and World War II and built a powerful postwar economy shared a set of beliefs: appeasing enemies never works; alliances matter; and America is great, as Alexis de Tocqueville said, because America is good.

George H. W. Bush was the last American president from that storied generation. In 1942, Secretary of War Henry Stimson gave the commencement address at Bush’s graduation from Andover. The speech was about fighting for freedom and democracy. Stimson told the graduates to go to college before they went to war, but Bush didn’t listen to that. Days later, on his eighteenth birthday, he enlisted and soon became the youngest pilot in the navy.

When I covered his 1988 presidential campaign for Newsweek, I learned that Bush bailed out of his TBM Avenger near the island of Chichijima in the South Pacific, where cannibalistic Japanese soldiers were said to be eating the livers of downed American aviators. With his two crewmates dead, he gave himself first aid and sat for four hours in his inflatable life raft before being rescued by a submarine.

Bush said he spent his time in the ocean thinking about his next meal; his fiancée, Barbara; and . . . the separation of church and state embedded in the Constitution. Lots of jaundiced reporters—including me—snickered at this, assuming that Bush was just trying to show moderate voters that he hadn’t sold out entirely to the Christian Right.

Perhaps so, but shame on us. The young pilot was also expressing a genuine motivation for his service. George Bush, Jim Alter, and thousands of other brave volunteers were risking their lives for an idea. When I recall the Greatest Generation nowadays, I think about Trump calling veterans and dead soldiers “losers” and “suckers.” A personal, political, and occupational question reverberates in my head. It’s a question, to be honest, that keeps me up at night:

What am I doing to help defend democracy and save the Constitution? At any other time in my adult life, this would be a grandiose, laughable question. Not now.

Unlike Dad and Bush and the combat reporters I’ve known who have died abroad doing their jobs, I don’t have to risk my life. I just have to inconvenience myself a little to bear witness—do my job—and urge others to get into the fight in whatever way they can.

It’s a fight alright. From the start, Trump called the press “the enemy of the people,” the exact words of Stalin, Hitler, and Mao.

When I heard this, my first reaction was: No, we represent the people (as the founders intended when they singled out the press for protection in the Constitution) and you are the enemy—of decency and democracy. But then I thought that descending to Trump’s level by describing even the most odious character (e.g., Trump) as the “enemy” takes us down a path toward violence. We have to fight hard and sometimes get personal, but stay decent.

Democracy is supposed to be America’s civic religion. It’s certainly mine. Trump doesn’t believe in this creed. He and J. D. Vance are classic nationalists, who believe not in the power of ideas but in the idea of power.* They’re blood and soil, divide and conquer, might makes right. This is how demagogues and despots have scarred human history.

I’m glad that Dad’s gone and can’t see all this.

HONEST ABE

I can trace my fascination with politics back to a single afternoon of dorm room small talk.

In 1948, my mother, then Joanne Hammerman, had an experience that would change her life and, by extension, mine.

As a senior at Mount Holyoke College, she was assigned to give Eleanor Roosevelt a tour of campus. After the tour was over, Eleanor asked her, “Now where do you live, Joanne? I want to see your dormitory.” When they arrived, the most famous woman in the world—the author that year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—plopped down on Mom’s bed and said to this Jewish girl from a non-political family in the Chicago suburbs, “Now tell me all about yourself. Do you want to help make a better world?”

Mom was dumbfounded. Eleanor Roosevelt was asking about her! From then on she was intensely interested in public affairs and intensely curious about other people, the foundation of both good politics and good journalism. She could be blunt and unfiltered, but her belief in working within the American political system to change lives never wavered, and she infected first her husband and then her children with it.

After the war, Dad began working in his father’s wholesaling business. In the 1920s, the Harry Alter Co. distributed Majestic Radios, the Apple Computer of its day (until it collapsed in the Crash). Someone in the family saved a 1928 invoice for a $167.50 radio sold by Harry Alter to “Benito Mussolini, Rome, Italy.” Il Duce (“The Leader”)—who must have liked Majestic’s motto, “the Mighty Monarchs of the Air”—was popular then in both Italy and the United States.

My parents were married in 1952 at Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel, where the phrase “smoke-filled room” was coined to describe how the Republicans nominated Warren Harding there in 1920. Mom was already a pioneer for women in politics, serving alongside a young county official named Richard J. Daley as an officer of the Young Democrats of Illinois. Daley would soon become the most powerful mayor and party boss in the country—a local Trump, only a thousand times smarter and more competent.

At the 1952 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, my parents worked to nominate Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson for president. Adlai was derided as an “egghead,” which meant an intellectual. A woman told him that he had the votes of every thinking American. “That’s nice, ma’am,” Adlai replied. “But I need a majority.” He didn’t get one. Retired General Dwight D. Eisenhower—with grievance-nursing Richard Nixon as his running mate—crushed Stevenson in November and again in a rematch in 1956. The lesson I later drew was that elite opinion has little to do with winning elections.

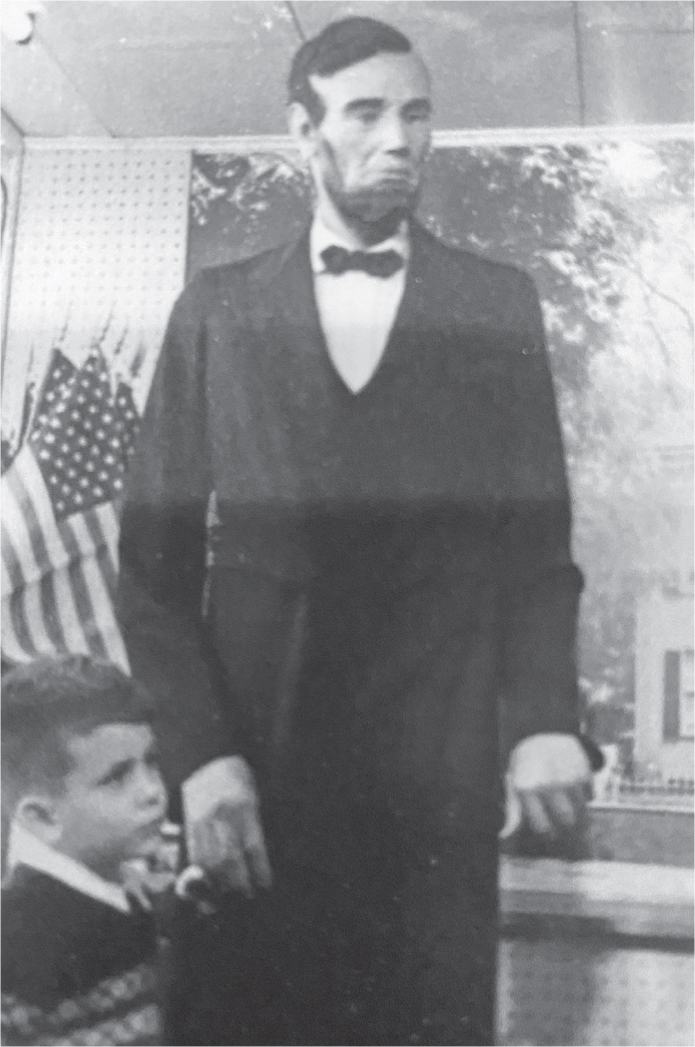

I was born the year after that second defeat, and by the time I was three, I was smitten with my fellow Illinoisan, Abraham Lincoln. At dinner parties, my parents hauled me out in my pajamas to discuss Honest Abe and recite all the presidents in order in a made-up song that I later taught my siblings and eventually my children.

My earliest memory in life is of Mom and Dad leaving us with a babysitter in 1960 when they flew to Los Angeles to see John F. Kennedy nominated. (“Whistle while you work! Nixon is a jerk!” was the song my older sister Jennifer taught me that summer.) My uncle, Bill Rivkin, was a Kennedy man and got an ambassadorship out of it.* The photograph of Uncle Bill and Aunt Enid in the Oval Office with JFK hung in our hall and fueled my youthful dreams.

My first campaign was in 1968. As a ten-year-old, I accompanied my parents as they rang doorbells on the South Side for Abner Mikva, an inspiring candidate for Congress. Mikva was running against incumbent Barratt O’Hara, a veteran of the Spanish-American War. I had a connection to Teddy Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill!

The author with his hero

That was around the time I learned of my father’s three-handshake history of the American republic. A drummer boy in the American Revolution could have shaken hands with a future Civil War veteran who, in fact, did shake hands with my father at a Chicago 4th of July parade in the late 1920s, who shook hands with (or kissed) grandchildren who may live into the twenty-second century.

After learning that American history is so short, I thought in second grade that I could write a short history of the country. I made it about two or three pages in.* Dad called me the only American historian who didn’t know how to read. When I finally learned, I inhaled Landmark Books about presidents and Mike Royko’s funny and pointed columns in the Chicago Daily News.

My little friends played with Legos and dinosaurs. I preferred Lincoln Logs, of course, and on the wall of my room I hung a copy of the Gettysburg Address (which I memorized) and a Styrofoam eagle, above the seal of the president of the United States, with an olive branch in one talon and arrows in the other. I also hung a 1964 Sports Illustrated poster of Cassius Clay (soon to be Muhammad Ali) decking Sonny Liston.

MLK

In 1966, when I was eight, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was living in a slum on the West Side of Chicago. He was there to draw attention to the plight of the urban poor and to pressure Mayor Daley for concessions on housing. A local politician had planned to host a party for King to raise money for a big civil rights rally at Soldier Field, but he feared Daley’s wrath. So he asked my parents to do it, and one spring night, King and his Chicago associate, Al Raby, came to our North Side house. The haul was disappointing—just a few hundred dollars, my father recalled. Many of my parents’ white friends didn’t show up because they, too, feared alienating Daley, whose iron grip on Illinois Democrats was as strong as Trump’s hold on Republicans would later become.

I got King’s autograph on the lined paper of my school notebook. The next day I stood exactly where he did in front of our fireplace and tried to recreate the mini “I Have a Dream” speech he had softly delivered. Could I stand up for justice like him? It wouldn’t be easy. That summer, I read in the Chicago Sun-Times how King was pelted with rocks when he marched through Marquette Park.

I wish I could report that I began my journalistic career by covering King in my handwritten newspaper that Dad xeroxed at his office so I could deliver it to the neighbors. Instead, I covered the Cubs (Wrigley Field, where bleacher seats cost a dollar, was only six blocks away) and wrote a banner headline that read: JON LOSES FOUR HARD BALLS IN THE BUSHES IN ONE SUMMER.*

For years, I took my unusual childhood experiences for granted, from attending campaign rallies in a stroller to skipping school every Election Day to work a precinct. Mom brought us to see the Beatles at Chicago’s Comiskey Park when I was seven and to see Hair (with full frontal nudity) when I was eleven. This was life as an “under-deprived Alter,” as my wife, Emily, later put it. We weren’t rich or spoiled, just exposed—to everything.†

Mom was, by all accounts, a force of nature. In third grade, my interest in history took a back seat to sports—Cubs, White Sox, Bears, Blackhawks, and a brand-new lousy basketball team called the Bulls. She marched into the Francis W. Parker School and confronted the teacher, Mrs. Horst. “My son could have been the next Henry Steele Commager,” she scolded, referring to the renowned historian. “And now you’ve made him into just another little boy!” I had no idea who this Commager was, but I was relieved that Mom didn’t tell Mrs. Horst her real career ambition for me—to be the first Jewish president of the United States.

I considered that occupation but also weighed being a TV anchor. On stage at school, my friend Casey and I re-created The Huntley-Brinkley Report, which, like the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite, was seen every weeknight by about twenty-five million people, more than five times today’s evening news ratings and ten times today’s top cable ratings, even though the country was only two-thirds the size that it is now. I played David Brinkley. “Goodnight, Chet,” I said to Casey, who played Chet Huntley. “Goodnight, David,” Casey said, completing the storied sign-off.

CHICAGO ’68

The summer I was ten, I was footloose at the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention. Having seen war, Dad hated it and was working for the peace candidate, Gene McCarthy; Mom had a job on the staff of Hubert Humphrey, who won the nomination that year without entering a single primary. A McCarthy aide saw my parents eating together in the Haymarket restaurant, soon to be the site of violence, and reported back to headquarters that Mr. Alter was conspiring with a female Humphrey operative. “That’s my wife!” Dad said.

Even as a kid, I could feel tension between anti-war protesters and police mounting on Michigan Avenue. We fled by car through Grant Park, and soon after, images of police clubbing demonstrators there would be flashed around the world. I have no idea why my parents let me go back the next day. But I can still see the glint of the National Guardsmen’s bayonets and smell the stink bomb that a protester threw into the lobby of the Conrad Hilton hotel.*

In 1969, federal prosecutors were determined to send hippies and Black radicals to jail for disrupting the previous summer’s convention. The result was the Chicago Eight Trial, with Judge Julius Hoffman—one of the worst federal judges in the country—presiding. Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, had been in Chicago only briefly during the convention and was completely innocent of any conspiracy to disrupt it. With his lawyer hospitalized, he protested to the judge that he lacked legal representation.

Judge Hoffman didn’t like his tone. He ordered him bound and gagged in the courtroom, then severed him from the other seven defendants and sentenced him to four years in prison for contempt of court, an absurd sentence he never served.

I remember poring over the Sun-Times courtroom sketches of Seale shackled to a chair with a rag in his mouth—and feeling my conscience stirred.* But as bad as the racial politics of Chicago were in those days, I don’t recall any white politicians claiming, as Trump did with Kamala Harris, that a Black rival wasn’t really Black.

In high school, defining myself as an outsider, I chose journalism over politics. My mother seemed OK with it, perhaps because she was otherwise occupied. She was a tireless “professional volunteer,” as she called herself, spear-heading civic organizations, as many women of her generation did. But her big focus was getting women to run for public office. Our dining room table was given over to women’s causes, from races for state representative to unsuccessful efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

THE JACKIE ROBINSON OF CHICAGO GENDER POLITICS

In 1972, Mom went to see Mayor Daley on behalf of a women’s group she organized and bluntly told him that “women are people, too” and he should slate them for public office. This was a polite but bold request (not a “demand”) three years before wives were even allowed to have their own credit cards. She gave the mayor a list of accomplished women who, unlike her, were loyal to his “Machine.” Daley thought Mom was a pushy critic, but he was a clever politician. So he offered her a place on the Democratic ticket (primaries being a mere formality in Illinois in those days) for commissioner of the Metropolitan Sanitary District. Mom told “Hizzoner Da Mare’’ that she knew nothing about sewage. He reproached her in his flat, harsh-consonant Chicago accent, “Joan [her real name was Joanne], I thaaat you sa’d you wanted women in politicks.” She said yes.

It was just after the first Earth Day, and Joanne Alter—with the help of a field organization made up mostly of housewives—ran one of the first environmental campaigns in the country. That and the novelty of her sex propelled her from the bottom of the ticket to being the top vote getter in Cook County. Over the years, I came to think of her as the Jackie Robinson of gender politics in Chicago, with Dad as her Denis Thatcher or Doug Emhoff. Friends had a joke campaign poster made: “When You Flush, Think of Me. I Won’t Stand for No Shit.”

Once in office, Mom didn’t. She made a lot of enemies but saved taxpayers millions and spearheaded the removal of industrial slag heaps in favor of beautiful walkways on the banks of the Chicago River, now a gem of the city. One day in the mid-1980s, her office phone rang. The caller was a community organizer from the South Side who was surprised to be put through to a commissioner. Mom always refused to have her calls screened; she believed she worked for the people and they deserved to be heard just as much as any big shot. The young man had a problem with a nearby sewage treatment plant that he discussed years later in a book called Dreams from My Father. That was the first time Mom ever spoke to Barack Obama.

Joanne Alter, civic pioneer

Mom owed her political career to Daley, but unlike Trumpsters, she wouldn’t take orders from the “Boss,” as the columnist Mike Royko called him. “Joanne, you’re one of those brainless braless broads who is ruining America,” another commissioner told her. That was mild compared with what he and other hacks said behind her back. “They couldn’t deal with a ‘girl from the kitchen’ making big budget decisions,” she told me years later, noting that path-breaking women engineers and lawyers she knew faced similar derision.

Remembering these men makes me think of Ted Cruz, Lindsey Graham, Kevin McCarthy, and other Republicans. They sound tough but are putty in the hands of their Dear Leader. After Mom opposed Daley’s reelection to a sixth term, he slated another candidate for lieutenant governor. She ran anyway, and lost with no regrets.

THINKING IN TIME

My work as a journalist began at sixteen when I wrote press criticism for the Chicago Journalism Review, a prelude to my job a decade later as Newsweek’s media critic. At Andover, which I attended for two years, I got the chance to interview Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa for the school paper. I asked him a tough question about the Teamsters muscling Cesar Chavez’s farm workers off the roads in California. “Where’d they get this kid?” Hoffa asked a thuggish aide, gesturing to me with a look that could kill. My interview turned out to be one of the last with Hoffa before he mysteriously disappeared.

At Harvard, I majored in history, with David Herbert Donald’s class on the Civil War my favorite. Things are bad now, but not nearly as bad as they were in the 1850s. I took a course at the Kennedy School taught by Richard Neustadt and Ernest May called “Thinking in Time: The Uses and Misuses of History.” Neustadt and I stayed in touch, and he helped me to embrace historical analogies in my Newsweek column but also to stay careful in how I deployed them.*

History doesn’t repeat itself, and when it rhymes, the meter is sometimes off. Columnists, historians, and the guy at the gym with a bone to pick should reject “presentism”—analyzing history through the prism of the present. That doesn’t mean rationalizing slaveholders or the callous treatment of women, but it does require avoiding facile historical analogies.

Beyond history and English classes and my senior thesis on Vietnam, I didn’t study much. I remember one class taught by a guy named Roger Revelle that had something to do with boring meteorological patterns. I ditched it often and only learned later that Revelle (like Neustadt) was a mentor to Al Gore and one of the founders of climate science.† My loss.

In the summer of 1978, I was an intern in the speechwriting office of Jimmy Carter’s White House. The emotion I remember is awe. This was what I had dreamed of when peering up at night at the styrofoam eagle and Gettysburg Address on the wall of my childhood bedroom. After a few weeks, I scored a hard pass for the West Wing, which allowed me to take my friends to see the Oval Office. If the president wasn’t there, the door was open and we could stand in front of the velvet rope and stare inside for as long as we wanted.

My boss was twenty-eight-year-old Jim Fallows, who later wrote that “Being Jimmy Carter’s chief speechwriter was like being FDR’s tap dance instructor.” Carter was a good president but a so-so speaker, especially compared to his successor, “the Great Communicator,” Ronald Reagan. One week, none of the grown-up speechwriters wanted to write Carter’s remarks at a North Carolina tobacco warehouse. I happily obliged. The only line of mine the president used was a joke saying he would bring back some tobacco for staffers caught smoking pot “so they smoke something regular for a change.”

In 1980, my former teacher, Alan Brinkley, got me a job as a research assistant to his famous and dry-witted father, David, my grade school role model, who was writing a history of Washington during World War II. David had been put out to pasture at NBC News and was still a year away from being hired by Roone Arledge at ABC News to launch his Sunday show, This Week with David Brinkley. That year, I loved interviewing old people who had known FDR personally. I vowed to become a journalist of some sort. My mother had planned for me to go to law school, but it slipped my mind.

NIXON HAD MY NUMBER

I came of age when Richard Nixon was president and I hate-watched him on TV every chance I got. Like many of my friends, I was inspired to go into journalism in part by the dogged work of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, whose articles in the Washington Post broke the Watergate scandal wide open.

Not long ago, I moderated a discussion with Woodward and Bernstein, both in their early eighties, on the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of their classic book, All the President’s Men. Bernstein, comparing Trump’s conduct to the treason of Jefferson Davis, explained how George Washington warned against a party very similar to the GOP in his Farewell Address, in which he described a dangerous faction that “kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasional riot and insurrection.” Woodward, who has spent more time with Trump than any other reporter, thought the similarities between Nixon and Trump were “stunning.” During the Watergate hearings, Sam Ervin, chairman of the Senate Watergate Committee, asked the larger question: “Why did this happen?” Woodward said the answer fits both Nixon and Trump: “A lust for political power. It’s a disease.”

I remember being influenced in the 1970s by a Watergate book called Breach of Faith, by Theodore H. White, whose best work I later tried to emulate. White argued that Nixon shattered a national myth that the presidency “would make noble any man who held its responsibility.”

Just before the 1988 election, I arranged to bring Nixon to Newsweek. I wanted to meet the man before he croaked. Toward the end of a long session between Nixon and the magazine’s editors, I asked him how history would view outgoing President Reagan.* He gave a perceptive answer: “Well, you have to distinguish between history and the historians,” he said. “The historians are like you, they’re liberal. If you’re a conservative, you go into business. If you’re a liberal, you write history and journalism.”

Nixon—this man I despised—had my number. He had, as they say, seen me. These days, as I weigh how to respond to Trump, I have to see myself and my responsibilities more clearly. Historian and journalist. Bearing witness. That’s all I got.

Is it enough? In Woodward and Bernstein’s day, aggressive journalism brought down a president. Nowadays, reporters still break big stories, but the fragmentation of the news business has dramatically curbed the influence of people like me. That’s fine, but I worry that readers now seek and receive (through algorithms) “news” that mostly validates their worldview. There’s a big difference between a fact-checked 1988 Newsweek cover story and “I read it somewhere online—can’t remember where—but it must be true and it really pissed me off!”

THE NIXON PARDON

I’ve done a 180-degree turn on the Nixon pardon—actually a flip-flop on a flip-flop. When Gerald Ford granted it in 1974, I was in high school and strongly opposed the decision. Later, Caroline Kennedy gave Ford the Profile in Courage Award for a decision that helped cost Ford his presidency.*

Over time, I and a lot of other people also decided that in retrospect he deserved the award—that the pardon was necessary to help heal the country. I wanted to talk to Ford about it and had my chance in the summer of 2000 when our family was on vacation in Colorado. I took Emily and our children with me to Ford’s ski chalet in Beaver Creek. As gracious Betty humored the kids while packing for a trip, I asked the former president about the pardon, and he offered a vigorous defense of it.

For years, the pardon seemed prudent because we thought Nixon was an aberration and that basic democratic accountability had been achieved. But by short-circuiting a trial of Nixon for his Watergate crimes, the pardon set a harmful precedent and should not have been issued. It left open the question of whether the president is above the law. “When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal,” Nixon told British television host David Frost. Fifty years after Nixon’s resignation, the Supreme Court—in Donald J. Trump v. United States—essentially agreed.

CHARLIE PETERS

On Thanksgiving Day 2023, I saw a New York Times bulletin on my phone that Charles Peters, the founder and editor of the Washington Monthly, had died. I left the living room and wept in the hall.

Charlie was ninety-five, so the news was hardly unexpected. But for me, Jim Fallows, and many of the other magazine writers and editors in our informal Washington Monthly alumni association, it was like losing a second father.

Charlie hired me in 1981 for a princely $8,700 a year. He expected that I and his other young editors would work eighteen-hour days doing everything from taking out the garbage to writing cover stories for two years before graduating to something bigger in journalism. I was twenty-three and intimidated by his patented “rain dances,” where this squat, raccoon-eyed, West Virginia iconoclast would jump up and down and explain at a high-decibel level what was wrong with your article, the government, the country—and you.

The abuse was worth it, because eccentric Charlie was one of the few genuinely original thinkers I’ve ever met. He believed in the compassionate ends of liberalism but was often critical of the mindless means of achieving them—and of the smug pieties of many on the left. As we learned to meld idealism and skepticism, he urged us to fasten an anthropological lens on our reporting, as if Washington politicians and bureaucrats were some exotic tribe in the South Sea islands. Charlie taught us to appreciate human complexity by writing “something bad about the good guys and good about the bad guys.”

Charlie and I last spoke in the spring of 2023 as he sat propped up in his basement, surviving thanks to an oxygen machine and the glow of an artificial Christmas tree that—his own person to the end—he kept lit all year long. We talked about his road trips with JFK during the critical 1960 West Virginia primary, and agreed that Trump was the exception who proved the rule—the only bad guy about whom there was nothing good to say.

ROY COHN

Charlie was the one who got me a job at Newsweek, where I spent twenty-eight years as a New York–based writer, senior editor, and columnist. Early on at Newsweek, I covered the media, and that brought me into contact with a figure who years later would cast a shadow over Trump’s criminal defense team. In 1985, S.I. Newhouse, heir to a newspaper fortune, bought the New Yorker. The week of the sale, I learned that one of Newhouse’s friends was Roy Cohn, the infamous New York lawyer. As a young man, Cohn helped prosecute Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage. He went on to be the top aide to Senator Joseph McCarthy, the most dangerous postwar American demagogue until Trump.

I called Cohn, who told me that he and the new owner of the New Yorker were not just friends, but best friends from Horace Mann School in the Bronx.

Cohn informed me that every morning at 6 AM, he, Newhouse, and their other best friend from high school, Generoso “Gene” Pope Jr., who founded the National Enquirer with a loan from New York crime boss Frank Costello, talked on the phone. That was the lede of my story, which I was later told almost blew the roof off the old New Yorker building on 44th Street: “Our new owner’s best friends are Roy Cohn and the founder of the National Enquirer? We’re toast!” It turned out that Cohn and Pope did nothing to harm their best friend’s new purchase, which Newhouse kept prosperous and strong editorially until the day he died.

Roy Cohn did a lot for Trump. He represented him in the 1970s after Trump and his father were sued by the Nixon administration’s justice department for blocking Black people from renting apartments in their buildings. Fred Trump had been arrested at a Ku Klux Klan rally in New York in 1927, and the poisoned apple didn’t fall far from the tree. Fred Trump III later reported that he heard his uncle use the N-word.*

Cohn also represented big-time mobsters, including Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, Carmine Galante, and Paul Castellano, the latter of whom was whacked by John Gotti, the original “Teflon Don” before the New York tabloids bestowed that title on Trump. These gentlemen were part of what federal authorities called “the largest and most vicious criminal business in the history of the United States.” Starting in 1979, “Fat Tony” struck a deal through intermediaries with the brash young developer: Trump would pay a mobbed-up construction company a premium for ready-mix concrete in exchange for labor peace with the mobbed-up unions he needed to build Trump Tower. Later, when erecting his casino in Atlantic City, Trump’s contractors dealt with a Sopranos-style New Jersey mob called “the Young Executioners.”

I didn’t know it, but at the time I talked to Cohn, he was dying of AIDS. The next year, Trump and Barbara Walters were among those testifying as character witnesses before the bar association after Cohn was credibly accused of ripping off a clueless elderly client. Just weeks after Cohn was disbarred, as Cohn’s secretary reported, Trump dropped his terminally ill mentor “like a hot potato.”

When he was president, Trump often asked, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?” He meant, Where’s my brilliant and surpassingly unscrupulous lawyer who would do anything to win? Too bad they couldn’t locate one for the New York trial. It would be fun to watch a reincarnated Cohn in the courtroom. I don’t think the jury would like him.

PEZ-DISPENSER PRESIDENTS

Since 1994, my family has lived in a Queen Anne Victorian house that was built in Montclair, New Jersey, during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes.

President Hayes has a place in our home, along with almost all of the other men who have held the highest office. We’ve got silver spoons of presidents, supermarket figurines of presidents, bobbleheads of presidents, paintings of presidents (including one by our daughter Charlotte of Martin Van Buren), bookends of presidents, and Pez dispensers of presidents. Did I mention the busts? We have bronzes of Washington, Lincoln, FDR, and JFK, and a wax Nixon, plus a foot-high peanut with Jimmy Carter’s grin and a classic print of Obama by Shepard Fairey.

There is one president whose likeness does not appear anywhere in our home. I think you can guess who he is.

TRUMP’S SHOPWORN HAIR SALON

In 1991, I was interviewed for a documentary about Trump’s business career and said two things: Trump was not the richest real estate developer in New York, much less the United States, as he insisted. And Trump was lying when he claimed Mikhail Gorbachev planned to visit him at Trump Tower. Both the Soviet embassy and the State Department told me this was complete bullshit—never any such plans.

The film, a critical look at his bankruptcies called Trump: What’s the Deal?, was underwritten by the billionaire Leonard Stern, who owned the Hartz Mountain pet food company. Trump paid Stern to squelch the film—a kind of early catch and kill—and I received a harsh letter from one of Trump’s lawyers threatening to sue me for defamation. I was young and a little intimidated. But when I showed the letter to Newsweek’s attorney, she laughed and said, “Join the club.” Nothing ever came of the lawsuit, of course.

Six years later, Trump had completely forgotten the flap over the film. I needed a sound bite for a TV piece and—like a lot of New York reporters—knew where to get one. Calling Trump a publicity hound in those days was unfair to hounds. We sat down in his Trump Tower office, which looked like a shopworn hair salon where the owner insists on hanging photos of himself between the mirrors.

This was for a TODAY show story about how everything in America is now super-sized, from McMansions to coffee cups at Starbucks. He tried to be thoughtful about the trend but did not succeed. We included him in the story anyway.

In the years that followed, I tried to think about Trump as little as possible. He was just an obnoxious celebrity who embarrassed New York in the eyes of the world.

Unfortunately, by 2009 he was impossible to ignore. Trump believed in Joseph Goebbels’s “Big Lie” technique, which means not just lying with relish but pushing outlandish lies so incessantly that they worm their way into public consciousness. He began with the absurd claim that Barack Obama was not born in the United States. After Obama, as president, released his birth certificate, Trump just moved on to the next of more than thirty thousand other documented lies. Trump’s lies were picked up by the Tea Party, a huge and now forgotten movement that hassled Obama for years before morphing into MAGA, which in turn spawned QAnon and its insane conspiracy theories.

I made a point of listening to some of Trump’s lies at one of his 2016 rallies in New Hampshire. Standing in the crowd, I sensed an air of menace, especially when the crowd turned on reporters gathered near the camera stand, booing them on Trump’s cue. But the crowd seemed happy and entertained, and there was power in that.

The weekend before the 2016 election I was with Vice President Biden when he campaigned for Hillary Clinton at a lackluster rally in Pennsylvania. Afterwards, a student at Bucks County Community College told me that as many as half of his classmates were for Trump. I asked why. He said it was because Trump was funny. That’s when I knew Hillary Clinton was in deep trouble. Many Americans ignore or indulge Trump’s norm-breaking because they view him as they would an eccentric uncle telling gay jokes at the other end of the dinner table.

I’ve rarely tried to report on Trump World and here’s why: At the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland, I ambushed Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign chair (and later a jailbird), and asked him why Melania Trump plagiarized Michelle Obama in her speech the night before, and why support for Ukraine had been mysteriously deleted from the Republican platform. He was pleasant enough but didn’t even bother with the usual spin. He simply denied everything, which was preposterous.

Since then, I have steered clear of these guys even though I know they are prodigious leakers. That’s because I’ve long subscribed to the maxim that a fish rots from the head—Trump’s bottom-feeders are serial liars, too, so why waste time trying to figure out if they’re lying 50, 75, or 100 percent of the time?

The feeling, of course, is mutual, not just from Trump World but from the broader MAGA universe. Despising the press is hardly new. Sixty years ago, Barry Goldwater’s delegates at the 1964 Republican National Convention loudly booed reporters at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. But it’s worse now. After the 2016 election, I asked a friend from South Carolina why so many people voted for Trump. “Because they hate you,” he said—not me personally, but everything that I, as a “lamestream” journalist, represent.

INSIDE THE BEAST

Bret Stephens, a conservative columnist for the New York Times, asked me recently: What’s worse, covering up hush money payments to Stormy Daniels or lying under oath about Monica Lewinsky?

For me, it’s not a close call. Both involved law-breaking, but the stakes were higher with Trump. In 2016, Trump did more than lie about sex; he took part in a conspiracy aimed at securing his election. In 1998, Bill Clinton lied like any cheating husband—to avoid embarrassment. One thing is for sure: the reaction of Republicans was worse. After they denounced Clinton, they didn’t just back Trump, they anointed him. By contrast, Democrats all chastised Clinton and breathed a sigh of relief that he wasn’t eligible for a third term.

Thinking about all of this took me back to the 1990s. That was the pre-9/11, pre–Iraq War, pre–Great Recession decade of peace and prosperity—the era when we had the leisure to obsess over Clinton’s sex life and the O. J. Simpson trial.

I’m not ashamed of my coverage of sex and politics but not proud of it, either. Much of what I wrote about Gary Hart, Bill Clinton, and, later, John Edwards, was prompted by tawdry articles in supermarket tabloids that we in the mainstream press thought could not, alas, be ignored.

My guidance in matters of sex and presidents came from Charlie Peters, who in 1979, at the time Ted Kennedy was challenging incumbent Jimmy Carter, published a widely read article by Suzannah Lessard in the Washington Monthly entitled “Kennedy’s Women Problem—Women’s Kennedy Problem,” that argued persuasively that Ted Kennedy’s philandering and cavalier treatment of women should be openly discussed. Charlie wrote that the sex lives of presidents and presidential candidates—but not senators or governors—were newsworthy because “We should not have to wonder from whose bed the commander-in-chief will be summoned at the moment of nuclear decision.” He wrote this in the context of saying that he knew and revered JFK and didn’t think his womanizing was disqualifying, but that friendly reporters should not have covered for him.

So aside from the legalities, is it necessary for the public to know that Trump had sex with a porn star when his wife was pregnant? I vote aye—and still believe that when vetting candidates for president, everything is fair game.

After a rocky start, Clinton led the country through eight years of relative peace and prosperity. According to a book by Howard Kurtz, Clinton said of me: “Alter bites me in the ass sometimes but at least he knows what we’re trying to do.” Sounds about right.

In 1997, a senior White House aide asked if I wanted to come down to Washington and interview for the job of chief speechwriter. I was tempted but decided that a job interview would compromise my column if it didn’t work out, so I immediately declined. Thank God, because the next year I would not have enjoyed cranking out the party line on the allegations against Clinton in the Monica Lewinsky case.

Lewinsky was a twenty-two-year-old White House intern when Clinton first kissed her, before they moved on to phone sex, an unlit cigar in her vagina, and tell-tale stains on a blue dress. I opposed his impeachment but supported censure, which I still think is the right punishment for lies about sex that do not rise to the level of the “High Crimes and Misdemeanors” required by the Constitution for removal from office (like, say, extorting the government of Ukraine or attempting a coup). But in retrospect, it’s remarkable how many Democrats defended him, including prominent feminists who would later champion the #MeToo movement. Imagine if he’d done all of that now—he’d be forced to resign before lunch.

Of course the rules are different for Trump, whose base didn’t care at all when he was found in a civil trial to have sexually assaulted E. Jean Carroll in a changing room at Bergdorf Goodman. Same for his involvement in Jeffrey Epstein’s harem or with Stormy Daniels. Swing voters—especially women—may not be as forgiving.

Like Kennedy’s many dalliances, Clinton’s sins did not discredit his presidency. But his handling of the matter did make it easier for men like Gary Hart, John Edwards, and Donald Trump to play the victim.

All told, I interviewed Clinton seven times when he was president, and all but one involved foreign affairs or domestic affairs, not the affairs and other sexual encounters that were causing him such problems. The exception proved memorable.

After he was impeached in part on the basis of reporting by my Newsweek colleague Mike Isikoff, he cut me off for a year or so. Then I spent time with Clinton touring impoverished areas of the country, and he agreed to let me interview him again. This was more than a year after he admitted the affair with Lewinsky, and no reporter had yet been able to question him about it. So in the fall of 1999, I rode with him in “the Beast” (the presidential limo) to Hartford, Connecticut, and posed what may be the most impertinent question I’ve ever asked anyone, though one I don’t regret:

“Are you seeking any psychiatric counseling for your self-destructive behavior, Mr. President?”

Clinton blew up. “I can’t believe you’re asking me that question, Jon!” I mumbled something about Tipper Gore working to end the stigma around mental health, then reframed the question to refer to his publicized pastoral counseling. He said that counseling was going well, calmed down, and finished the interview before he and an aide bolted the Beast without saying goodbye.

At the end of his term, I sought another interview with Clinton and was rebuffed. “After that ‘Are-you-crazy-Mr.-President’? question, no way,” his press secretary, Jake Siewert, told me. But here’s the thing about Clinton: Because he needs forgiveness, he forgives others. A year later, I got the first interview with him after he left office. “I can’t believe I’m giving my first interview to the house organ of Paula Jones,” he complained to me when I was shadowing him for a week at his Harlem office, referring to the fact that Newsweek had twice put his Arkansas accuser on the cover. But he cooperated and allowed me to question him for the first time about his pardon of fugitive financier Marc Rich, a decision that received a hundred times more negative coverage than all of Trump’s more egregious pardons combined.

Back in New York after the presidency, the Clintons let Trump ingratiate himself with them. He gave $100,000 to the Clinton Foundation and supported Hillary’s Senate campaigns; they attended his 2005 wedding to Melania at Mar-a-Lago. Just another celebrity transaction.

Then came 2016. Trump—reeling after the release of the Access Hollywood tape—brought three women who had accused Bill Clinton of sexual harassment or assault as his guests for his second debate with Hillary Clinton.

We all saw the resurrection of this tabloid drama. But another tabloid story—a story about Trump and a porn star—was hidden from view that fall, known only to Trump, Michael Cohen, and a couple of others. It would surface much later in the dusty files of the Manhattan DA.

UNCLE FUN

Getting to know John McCain did as much as anything to nourish my nonpartisan civic faith. I fell for him harder than a journalist should for a politician. We met in 1995 when he and his fellow war hero and Senate colleague, John Kerry, were providing cover for President Clinton (like Trump, a draft dodger) to normalize relations with Vietnam. I told McCain I was headed for Vietnam, and he set me up with Communist officials who offered me strong evidence that—contrary to feverish conspiracy theorists—no POW/MIAs were held or buried there.

McCain was a bad boy with a good heart and we called him “Uncle Fun.” He spent two of his five and a half years of captivity in North Vietnam in solitary confinement and now craved company. “I’m Luke Skywalker getting out of the Death Star!” he’d exclaim.

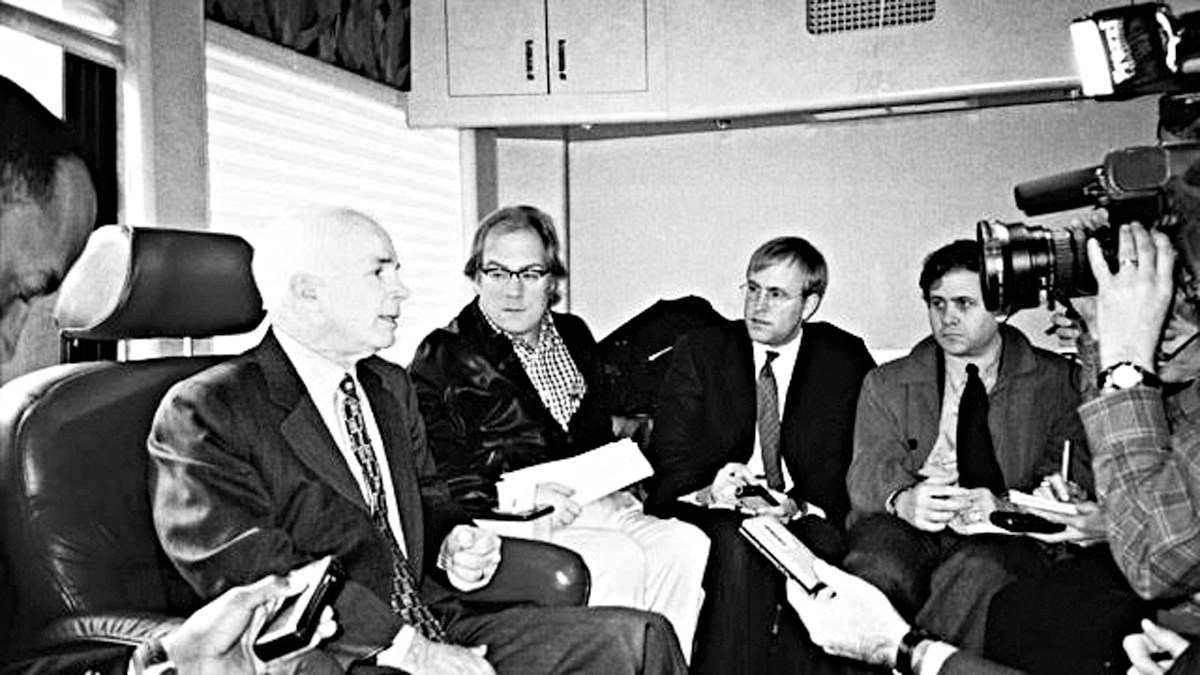

I was a frequent passenger on “the Straight Talk Express,” his 2000 campaign bus where day after day about ten reporters got to talk to the candidate for five or six hours straight about everything from being viciously beaten by his captors at the “Hanoi Hilton” to why he felt Mitch McConnell and many of his Republican colleagues were jerks.

McCain’s positions on most issues were too conservative for my tastes but that didn’t matter in primaries. He was essentially running to be another John F. Kennedy—“to inspire a generation of young Americans to commit themselves to a cause larger than their own self-interest,” he’d say. Just mentioning the need for inspiration was inspiring to me, and the contrast with Trump—who has no ideals of any kind—could not have been more stark. In 2015, Trump said of McCain, “I like people who weren’t captured.” I was surprised and disappointed that this comment did not end Trump’s campaign. That was an early sign that, politically, we were no longer in Kansas.

Aboard the “Straight Talk Express” with (left to right): John McCain, strategist Mike Murphy, journalist Jonathan Karl, and the author

Before the South Carolina primary, Jeff Zucker, the executive producer of the TODAY show, arranged a wildly expensive live shot aboard McCain’s Straight Talk Express, which in those days required two hovering helicopters and a fleet of satellite trucks. After Katie Couric tossed to me to open the broadcast, I said, “Good morning, Senator McCain,” and he replied, “Good morning, Jonathan, you communist.”

When Trump says something vile (i.e., almost every day), he often claims afterwards that he was just joking. It’s a clever way of revving up his base while simultaneously slagging his critics for lacking a sense of humor and denying responsibility for the inflammatory remark. But the “jokes” are more than just part of his lounge act. Most of them also reflect his actual views. Even sick humor contains truth.

In McCain’s case, the “communist” jab really was a joke, and a funny one. He was amusing in private, too, and proved more even-keeled than his reputation suggested. While he tongue-lashed Senate colleagues for selling out to special interests, he treated his loyal staff with great respect.

I was in his Columbia, SC, hotel room when his aides told him that exit polls showed he had not only lost to Bush in South Carolina, but had lost among veterans. Racists in Bush’s campaign had—without Bush’s knowledge—spread the word that McCain fathered a Black daughter. This was an unconscionable attack on eight-year-old Bridget McCain, whom the McCains had adopted from a Bangladeshi orphanage in 1991. Cindy McCain, sitting next to me on a small couch, burst into tears. John, who had seen a lot worse in Vietnam, calmly said, “It’s just politics, honey.”

I put my columnist’s thumb heavily on the scale for McCain, who began losing a string of primaries to Bush. On a day off from the 2000 campaign, he had me and John Dickerson of Time to his ranch near Sedona, Arizona, where he kept four “Turbo” grills. His war injuries prevented him from raising his arms above his shoulders, so hiking and moving from grill to grill were his only forms of recreation. His specialty was spicy chicken, which he patiently grilled on low heat “to cook everything bad out of it—a purification thing.”

For me, McCain embodied a purification ritual in American public life. Instead of bitterness, great suffering can bring grace—if survivors tap their curiosity, idealism, and sense of humor. Even so, the rest of 2000 tested my faith in democracy. After defeating McCain, Bush beat Al Gore in the disputed 2000 general election, despite losing to him in the popular vote (the first time a president was elected with a minority of the popular vote since Benjamin Harrison in 1888).*

In 2008, McCain won the GOP nomination after Rudy Giuliani blew up on the launchpad. By then we had drifted apart, mostly because he had the poor judgment to name Sarah Palin to the ticket. I angered his staff by writing that he didn’t know how to use a computer—a relevant detail for a possible future president—and he knew I was partial to Obama.

Five years after that, we reconnected when he agreed to do a cameo on a comedy I was working on.* John loved show business. During his captivity, he entertained the other American POWs by acting out all the parts in movies. One day on the campaign trail, I watched a conspiracy monger confront him. “And Angela Lansbury turned over the queen of diamonds,” he deadpanned, a reference to nutjobs calling him “the Manchurian Candidate.”

McCain had limited patience in life and art. If he hadn’t succumbed to brain cancer in 2018, Trump’s “January 6th Choir” would have killed him.

FEARLESS

On Super Tuesday 2004, I was in a Starbucks in Penn Station when a doctor called to say that a CT scan of my abdomen showed a large tumor, with extensive lymph node involvement.

I endured a chatty lunch with anchors and political reporters at the Palm restaurant, where we bet on the outcome in Super Tuesday states. My head was throbbing as I absorbed what I knew to be true: I had cancer. Our group hosted a guest that day—Roger Ailes. I remember wondering: Why do I have cancer and Roger looks fine?

The diagnosis was worse than I expected: stage four mantle cell lymphoma. Two-year survival rate of 50 percent. The five-year survival rate was so bad they didn’t want to tell me.

Dr. Andy Zelenetz and the Sloan Kettering team saved my life. I was there for twenty-nine days in all, including the bone marrow transplant. Our children—Charlotte, Tommy, and Molly—handled it remarkably well, in part because we didn’t overshare the details.

In the hospital, I set my doubting nature aside—the crap I read online that understandably irritated Dr. Zelenetz—and listened scrupulously to doctors’ orders, which I later recounted in a long Newsweek article about my ordeal. Before I grew too weak, I even managed to write a column about New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey resigning after a gay sex scandal. Yep, I was still covering politics from my near-death bed.

I have a memory about Trump from this period. Because of my severely compromised immune system, I refused to shake hands, cheerfully telling friends that I was just following the example of germaphobe Donald Trump, who did the same without having cancer.

I never learned what caused my lymphoma, though I have my suspicions. After I recovered, I received a call from Joe Lhota, the former deputy mayor of New York. In the days and weeks following 9/11, I had accompanied Joe and his boss, Mayor Giuliani, on several shattering visits to Ground Zero, which struck me as the closest I will ever get to Dante’s Inferno. I thought Giuliani had been a bad mayor overall but respected his leadership after 9/11, a period that strengthened my patriotism. At lunch, Joe told me that he, too, had been diagnosed with lymphoma, and he thought we both might have gotten it from all that unmasked exposure to chemicals in the steaming pile of rubble.

In the last twenty years, the sword of Damocles hasn’t dropped. Not yet, anyway. The fear of recurrence never evaporates, but I don’t think about it much anymore. It’ll probably be something else that gets me—a heart attack or a Mack truck.

I love getting older, because I wasn’t sure I would. It’s a miracle I’m still here and have more time.

One of the things I don’t take for granted: the future of this country. We’re on a knife’s edge. I’ve never been a Voltaire guy, so I don’t understand retreating to cultivate one’s garden without any connection to the wider world. I don’t understand why ostriches put their heads in the sand. And I don’t understand how any person can be so happy-go-lucky or self-absorbed that their private life is not shadowed—at least part of the time—by the alarming condition of public life.

When I was sick, a friend of mine joked, “Oh, God, now you’re gonna get deep.” I told him he didn’t have to worry about that. But I did get more fearless, a quality in depressingly short supply in politics.

I’m not sure where Liz Cheney, Adam Kinzinger, Mitt Romney, Brad Raffensperger, Rusty Bowers, and a few other lonely patriots got their guts, or why so few of their colleagues in the Republican Party have any. One explanation is fear of violence; Romney said several of his Senate colleagues didn’t vote to convict Trump in his impeachment trial out of concern for their personal safety. But the larger reason is moral cowardice. When faced with a choice between power and conscience, only the bravest will listen to the latter.

ROGER AILES

To understand what Trump is doing to this country, you have to understand what Roger Ailes did to us first. A bad guy long before he was caught sexually harassing women, Ailes, like Trump, could dish it out but he couldn’t take it, as I learned when I wrote a satirical column about him in Newsweek in 2006. Ailes went crazy, writing me a charming letter that began: “Jon, I’m afraid your cancer has affected your judgment.” Later, he denounced me publicly and threatened to sue me after I described his paranoia in a book. I knew that just like Trump, Ailes would never follow through, so I didn’t care.

I did care that the new indoor records Ailes set for nastiness were, with the help of the internet, being matched and broken all over the place. It was as if the gossamer layer of basic human decency that we assumed protected us was a spider’s web after all. Ailes was a huge spider—the biggest and most influential of the era—and his poison spread through much of the national bloodstream.

Ailes and Trump had their ups and downs but were good friends in Manhattan for forty years. When Trump began toying with the idea of running for president, Ailes sent him strategy memos from Fox News headquarters, just as he had done for George H. W. Bush and his son. He died four months after Trump’s inauguration.

Whatever happened later between Trump and Fox after Ailes’s death, the work of the master was done. He had bolted the Republican Party to a powerful propaganda machine (and its imitators) and changed American politics forever.

OBAMA AND GRANT PARK

It’s often said that Barack Obama made Donald Trump possible; the backlash against him sent things spinning in the wrong direction. Maybe so, but Obama also made genuine, unbridled idealism possible. For a whole generation, he did what John F. Kennedy had done in 1960 and Kamala Harris would do in 2024. In that sense, the success of Obama’s presidency made the dread and disillusionment of the Trump Era feel even worse.

I met Obama in early 2002 when we were sitting shiva in Chicago for my Aunt Enid, the aunt whose photo with her husband and JFK in the Oval Office had helped fire my boyhood imagination. Enid’s son, Bob Rivkin, and his wife, Cindy Moelis (a work colleague of Michelle Obama), had been urging me to meet him, and here he was, this cocky Illinois state senator who had just lost to a former Black Panther for the House. Now he was heedless enough to be launching a long shot campaign for the U.S. Senate with a name that a year after 9/11 sounded suspiciously like Osama bin Laden. But he was impressive that day and grew more so over time.

Mom agreed. By 2008, she had Lewy body dementia, but she was clear enough for me to write a Newsweek column that detailed her “excruciatingly painful” choice between two candidates she knew personally and admired. She resented the sexist comments directed at Hillary Clinton (“Iron my shirts!” chanted imbecilic future Trumpsters in New Hampshire), but she finally chose Obama because she saw that her grandchildren were inspired by him. The next president was for them, she reasoned.*

Even so, Mom felt bad for Hillary and conflicted: A woman president was what she had been working toward for more than half a century. In more lucid moments, she never let me forget that a year earlier, Newsweek and Time both neglected to put Nancy Pelosi on their covers after she was elected the first woman Speaker of the House in US history. “That’s outrageous!” Mom said. And she was right.*

Obama’s decade-long run of political success is almost unprecedented in recent American political history and it’s a big reason why Trump resents him. He seems easygoing in public but can be tough and contemptuous in private. When the staff gets sloppy, he grows angry, as Jimmy Carter did.

Midmorning on Election Day 2008, I put Mom in her wheelchair and took her downstairs to the polling place in the Chicago nursing home where she lived with Dad. She was weak and disoriented but determined to vote one last time. I went into the polling booth with her, guided her hand to Obama’s name, and—like a machine precinct captain of old—helped her pull the lever for him.

On election night, I was in Grant Park, marveling that the children of police officers and of anti-war protesters were on the same sides of the park’s barricades now, celebrating together, forty years after that horrific Democratic National Convention broke the party and the country apart.

It felt good to be an American, with a brilliant Black president bending Dr. King’s arc of the universe toward justice. He was the face of a changing America—a new, more equal country, but one that proved threatening to millions of its people, including a buffoonish real estate developer from New York.

My mother died a week after the election, and the president-elect found time to leave a voicemail message for me and my sister Jamie and to send me this email: “I loved your mom, and will miss her. I hope, despite the loss, that her remarkable life will be a source of celebration. Barack.” It was.

UN-TRUMP

Toward the end of the Obama presidency, I began work on a full-scale biography of Jimmy Carter. Like Obama, he was an UnTrump.

On the day in June of 2015 when Trump came down the Trump Tower escalator and announced his candidacy, I was in the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta and had to hustle over to a local studio to analyze it on MSNBC. On the air, I was right and wrong that day. Right in calling him a dangerous demagogue for attacking Mexican immigrants as “drug dealers, criminals, rapists” and wrong in discounting his chances of being the Republican nominee.

What I remember most is returning to the library, where for the next three years of research I could take vacations from Trump and find refuge in Carter’s integrity and decency. Turning the pages of Carter’s papers brushed away the Trumpist toxins.

Trump never got to live in my brain rent-free because Carter already occupied the premises. He was a much more complicated and thus intriguing person than a simpleton like Donald Trump could ever hope to be.

Over time, my eyes grew wide at the scope of Carter’s unheralded achievements. His presidency was a political failure—Ronald Reagan crushed him in 1980—but a substantive and often visionary success. Carter signed more major bills in one term than Clinton and Obama did in two—and more than ten times as many as Trump. In the six decades since Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, Carter’s legislative successes are rivaled only by Joe Biden’s.

And yet amid my many interviews with him about his epic American life, I grew annoyed with Carter when talk turned to Trump. Carter seemed to take more shots at Reagan and Clinton than he did at the new president. He’d gruffly acknowledge that Trump was divisive, then change the subject, usually to the Middle East.

I hoped Carter would use his moral authority to discredit Trump, but he was playing a longer game. Even in his nineties, he considered himself a player who needed to keep his options open in case Trump would let him get back in the action, as Secretary of State John Kerry had done when he welcomed Carter’s reports on his meetings with Putin and other world leaders. In early 2019, Carter wrote President Trump a long, smart letter about China, which Trump called “beautiful.” After they spoke on the phone, a pleased Carter seemed to me to be falling a bit for Trump’s flattery.

But within months, Trump started to trash Carter again, and it was clear he wouldn’t give him any assignment. By that summer, Carter was calling Trump an “illegitimate” president who had been put into office by the Russians.

ROSALYNN

When Rosalynn Carter died in 2023, I realized it is not just presidents who are capable of renewing my faith in our civic religion. It’s first ladies, too. In researching my book, I found a lot of people who had critical things to say about Jimmy, but no one had a single bad thing to say about Rosalynn, a tough-minded woman of many unsung accomplishments.

One example: Rosalynn convinced scores of states, most of them conservative, to require that children be vaccinated before entering school—a huge public health victory that Trump wants to reverse.

Rosalynn blamed Reagan, indirectly, for the Confederate flag flying on a porch across the street from their modest home in Plains, Georgia. She told me that he made Americans comfortable with their prejudices. “Just like Trump,” she said.

At her funeral, their daughter Amy read one of the passionate love letters Jimmy wrote Rosalynn when he was at sea as a naval officer. Amy told me a few years ago that her mother kept the letters in a drawer close by for seven decades.

I’m sure Melania would do no less.

EAVESDROPPING ON BIDEN

I’d learned over the years that Joe Biden knows the issues well and is no lightweight. Familiarity has bred respect. One day in 2009, I was sitting in his vice-presidential office when his secretary said Iraqi president Jalal Talabani was on the line. I got up to leave and he motioned me to sit down. For the next half hour, I eavesdropped on a master class in how a good politician massages another to get his way. Biden did that for Obama and for himself and has the legislative record to show for it.

As I pondered why Biden didn’t keep his pledge to be a “bridge”—a transitional president—and instead fought so hard to stay atop the 2024 ticket, my mind turned to 2016, when he was the outgoing vice president. For three months that year, I traveled on and off with him as I prepared a profile for The New York Times Magazine. He was a haunted man, bent by grief over the loss of his son, Beau, in 2015, but determined to stay in the arena in 2020. “I’ll run,” he told me on Air Force Two. “If I can walk.”

One night, en route home from South America, I looked at the vice president’s shoulder and thought I could see the chip. He was talking about how Obama aides referred to him dismissively as “Middle-Class Joe”—a moniker he was proud of, but not from the mouths of Ivy Leaguers whom he thought (often wrongly) looked down on him. There was nothing bitter and Nixonian here, but the class resentments weren’t far from the surface.

Obama and Biden had a close, complex relationship in the White House that I chronicled in my Obama books. They didn’t play golf together or socialize much, but their partnership was inventive, as I learned just before they left office. Both men—and former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta—confirmed for me that they had a secret code in meetings so that Obama could get the honest views of subordinates too inclined to agree with him. To keep the discussion flowing, Obama would not disclose his position. When the president leaned back in his chair, it was a signal for the vice president to chime in with the pre-arranged Obama-Biden view, which could then contribute to the debate without tilting it.

But in 2016, Biden was a little sore at Obama for backing Hillary Clinton over him for president. He was genuinely grateful to Obama for his emotional support after Beau’s death; the president, who had amassed some wealth from book royalties, even offered to pay the college tuition of Beau’s children. Biden didn’t take him up on it, but appreciated the gesture. And when Obama advised him that he was still too distraught to run, Biden agreed. But I could tell in 2016 that he felt conflicted about it.

That’s because Biden believed he would have beaten Clinton in the primaries and Trump in the general election.* This was unlikely. He finished fifth in the 2008 Iowa Caucuses, fourth in the 2020 Caucuses, and fifth in the 2020 New Hampshire primary. The brutal political truth is that Biden had been a rambling and unimpressive presidential candidate as early as 1988, when I first watched him bore the pants off audiences.

THE TRUMP COUP TRIAL

In 2022, I followed the January 6 Committee hearings like a frenzied fan. Bennie Thompson, Liz Cheney, Adam Schiff, Jamie Raskin, and all the other members of the committee became my demigods of democracy. They forced a tardy Merrick Garland to get with the program and start investigating the coup plot.

Jack Smith, the top-notch special prosecutor finally appointed by Garland, tried to make up for lost time with a streamlined indictment of only four counts and just one defendant: Trump. The question was whether he made up enough lost time to convict Trump before the election.

For a while, it looked as if he had. In mid-2022, we had real hope that both of Jack Smith’s federal cases could bear fruit—the big one in Washington and a winnable but less constitutionally significant one in Florida, where Trump was indicted for hoarding classified documents at Mar-a-Lago and, worse, not returning them when asked to do so. FBI agents raided Trump’s mansion and came away with a ton of incriminating evidence. Smith, fresh from trying Kosovo war crimes in The Hague, seemed to be on a roll.

The Florida case was viewed in legal circles as a slam dunk until it was assigned to Judge Aileen Cannon, a dim-witted Trump appointee and apparatchik. At every turn, she ruled for delay and more delay, even after being reversed by the appellate court. After the odds of a Florida trial before the election plummeted to somewhere between zero and none, I stopped reading stories about that case. Why bother? The lucky bastard had slithered free again.*

Meanwhile, the Trump coup trial, supervised by the formidable Judge Tanya Chutkan, was delayed by Trump’s immunity appeals, which he eventually won in the Supreme Court. But Smith’s case will likely survive in some form in a Democratic administration. If it does go to trial, it will be the most monumental test for the rule of law and the US Constitution since, well, ever.

VETERANS DAY

Dad always liked Veterans Day. He taught me as a kid that it was originally called Armistice Day in honor of World War I ending at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, 1918. It’s not a day to be taken for granted.

I can’t bear to imagine how he would react to Trump’s 2023 Veterans Day speech in New Hampshire, especially the part where he said: “We will root out the communists, Marxists, fascists, and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country, that lie and steal and cheat our elections.” Trump posted almost identical messages on the 4th of July and Thanksgiving. How patriotic.

It’s easy to make fun of this—the redundancy of “communists, Marxists”; the fact that communists are on the left and fascists on the right; the irony and gall of the party of Trump, Bannon, Giuliani, and their legions of goons-in-waiting calling Biden, Harris, Schumer, Jeffries, and millions of moderate Democrats like me “radical left thugs.” Calling my dad that!

Demagoguery is dangerous. A dictator’s first move is to dehumanize.

This is not a drill.

SMASHING THE GYROSCOPE

Over the years, I’ve tended to agree with Barack Obama’s observation that things are never quite as bright or as dark as they appear at the time. We muddle through. Events loom large for a while, then become just more flotsam floating down the river of history. To mix metaphors, it’s as if there’s an invisible gyroscope responsible for stabilizing our politics. If Harris wins, the 2024 election may well be remembered as the time when stabilization kicked in.

But unlike parliamentary systems where poorly performing prime ministers can be turned out of office any time, our system invests great power in one person for at least four uninterrupted years. That places a premium on the character of the president and of the other political actors who are charged with keeping him (or her) in check. What’s terrifying about Trump is that beginning in 2016 he hijacked not just the Republican Party but public life itself. The raised fist after he survived an assassination attempt is not just a powerful iconic moment of defiance; it’s a reminder that Trump plans to use that fist to smash this gyroscope, perhaps as soon as the aftermath of the 2024 election, which he will of course refuse to concede if he loses.

That’s what makes moments of accountability and the rule of law so critical. And that’s why it’s important to invest a sordid trial with the constitutional grandeur it now deserves.

*Vance stressed “home” and “homeland” over our founding ideas in his nationalistic acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention. His “Great Replacement Theory” lies about Democrats importing immigrants so they can vote for them, his denigration of single women, and his repellent policy proposals giving parents an extra vote for each child are all familiar fascist tropes.

*His son, my first cousin, Charlie Rivkin, who was four years old when his father died, grew up to become Barack Obama’s ambassador to France.

*Franklin Roosevelt had a similar problem. In 2005, while researching my book The Defining Moment at the FDR Library in Hyde Park, I noticed that in the 1920s, while recovering from polio, he set out to write a history of the United States but only managed to scribble a few pages.

*The legendary columnist Jimmy Breslin did better. When he was eight, he used his handwritten newspaper to cover his mother’s attempted suicide. I interviewed him for an HBO documentary, Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists, and asked why he did that. He was offended by the question. “I had to write an ahticle!” he honked from Queens.

†Emily and I tried to do something similar. My interview with Mikhail Gorbachev in New York happened to take place on Take Your Children to Work Day, 2001. I took them to it.

*Some analysts have made facile comparisons between the 1968 and 2024 campaigns. It’s true that President Lyndon Johnson stood down, just as President Joe Biden did, and that in both years the Democrats held their convention in Chicago. In 1968, the Democratic Party was deeply divided over the Vietnam War; in 2024, the Democrats are remarkably united.

*Thirty years later, I interviewed Seale and was struck by his lack of bitterness.

*As a reporter for the Harvard Crimson I got my first experience covering sex stories. I learned that two MIT women had slept with thirty-six men they identified by name and rated them one-to-four stars on their sexual prowess. The story was picked up by the pre–David Pecker National Enquirer.

†Gore deserves more credit than he gets. While he didn’t “invent” the internet, he secured much of the government funding that made it possible, which is all he ever claimed. Unfortunately, politics got in the way of his vision. When I interviewed him just before the 2000 election, he downplayed his climate-change agenda, which his campaign worried (with good reason) would hurt him in fossil fuel states such as West Virginia and Ohio that were already trending red. But without passion on climate, his campaign had a stolid uninspiring quality. That hurt him in a breathtakingly close election.

*When I was at Newsweek, I was too young to be assigned to interview Reagan in the White House, and after he left office, he was too old to sit down with reporters. So Reagan was the only president going back to Nixon whom I didn’t get a chance to question.

*My present for my college friend Caroline Kennedy on her twenty-first birthday was “soap on a rope” shaped like a microphone for singing in the shower. In an especially classy college boy move, I brought it over to her apartment at 1040 Fifth Avenue in a paper bag. “That’s the most phallic thing I’ve ever seen,” Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis said before turning on her heel to leave the room.

*Fred Trump III has a disabled son. In a 2024 book, he charged that Trump got tired of contributing to a medical fund for him and told his nephew, “Maybe you should just let him die and move down to Florida.”

*I was at a county building in Tallahassee, Florida, watching the counting of ballots when the conservative Supreme Court—hypocritically violating its own long-standing deference to states on election issues—ordered the counting stopped and handed the election to Bush. Gore’s graceful concession stood in sharp contrast to Trump’s shameful and criminal behavior after the 2020 election.

*In 2013–2014, I co-produced Alpha House, a two-season Amazon show starring John Goodman. The show, written by Garry Trudeau, was about four Republican senators who live in a man-cave on Capitol Hill. McCain played himself.

*One of Obama’s most powerful themes in 2008 was that it was time to “turn the page” generationally from the Clintons. Kamala Harris is making a similar argument against Trump. Ironically, the Clintons, Obama, Trump and Harris are all technically baby boomers, born between 1946 and 1964. But the early boomers have little in common culturally with contemporaries Obama and Harris, who were born in 1961 and 1964, respectively. The latter—shaped more by the 1970s than the 1960s—are more properly known as Generation Jones, which is named for all the lyrics of the era containing the name Jones.

*In 2012, I compensated a bit by inviting Pelosi to appear as part of the Joanne H. Alter Women in Politics and Government Lecture series at the Chicago Humanities Festival, which we established in memory of Mom.

*When Hillary wrote her book, What Happened, about the 2016 election, she came to Montclair on book tour. We assembled a few girls and young women to greet her in our home. I had been critical of Trump in my coverage but apologized to her for not doing more to illuminate the historic stakes.

*This was confirmed in July 2024 when Cannon dismissed the case, citing Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion in Donald J. Trump v. United States, the landmark immunity case. There’s still a chance the stolen documents case will be revived in a different judge’s courtroom.