Legend

PETER READ MILLER/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

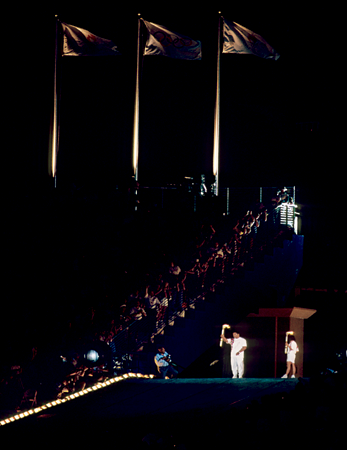

Ali, an American icon—a hero at last—prepares to light the Olympic eternal flame to open the 1996 Summer Games in Atlanta.

WE ARE, ALL OF US, MEN AND WOMEN OF varying degrees of achievement, stature and public renown. Only the largest of us are legends. From the world of sports these might include such athletes as Babe Ruth and Babe Didrikson Zaharias, Johnny Weissmuller and Johnny Unitas, Sam Snead and Slingin’ Sammy Baugh. And, most certainly, Muhammad Ali.

The legendary among us are not necessarily the best ever, but they are, somehow, the biggest ever. Their amazing feats are matched by charismatic personalities and personal narratives that often seem pulled from fiction. Legends possess a distinct and hard-to-define otherness.

In the thrilling late chapters of Ali’s boxing career, he moved from athlete to legend. Then, after his retirement in 1981—as this once controversial and, in some corners, reviled man came to be nothing short of beloved—this status was cemented.

Ali’s October 1974 adventure in Africa certainly played a large part in his elevation. The destination was a converted soccer stadium in Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The mission was to regain the heavyweight crown.

But that crown sat atop the head of the man mountain named George Foreman, undefeated in 40 professional bouts, 37 of which had ended in a knockout. “After a few blows from Foreman, the average heavy punching bag begins to look like a pancake,” Time magazine observed in the run-up to the fight. “So do most of his opponents.” Indeed, none of Foreman’s previous eight victims had made it to the third round.

Ali trained hard (not always his custom in his later years) and was in shape. “Last night,” he boasted, “I cut the light off in my bedroom, hit the switch, was in the bed before the room was dark.” He was greeted in Zaire as a conquering hero and was the great favorite of most of the 60,000 fans who packed the stadium for the four a.m. bell (scheduled for that hour in deference to viewers in the U.S.). “Ali, bomaye,” the throng screamed—“Ali, kill him!”

Ali came out circling the ring but then, after the first round, changed tactics completely and put himself against the ropes, covering up with his arms and gloves. He would later call this strategy “rope-a-dope”: While still landing hard punches whenever possible and leaning back into the ropes to avoid getting hit, he planned to absorb whatever abuse Foreman could visit upon him, then strike when the champ was exhausted. It worked. In the eighth round, with Foreman’s energy drained by ceaseless, fruitless punching, Ali hopped off the ropes, saw an opening and in a rush of energy hammered Foreman with a left and then a right, knocking him down to end the fight. The astonishing victory, as big a surprise as the first win over Liston, made Ali only the second fighter in history, after Floyd Patterson, to reclaim the heavyweight championship.

“Don’t ever match no bull against a master boxer,” he said. “The bull is stronger, but the matador is smarter.”

Ali successfully defended his title in three bouts that were unremarkable, save for the footnote that when Sylvester Stallone watched Ali fight Chuck Wepner, a gritty underdog, he was inspired to write Rocky.

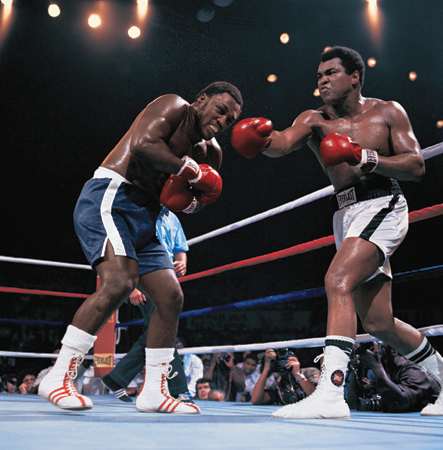

NEXT UP WAS ALI-FRAZIER III. THE FOREMAN FIGHT had been sufficiently momentous to merit an Ali-coined nickname, the Rumble in the Jungle, and for this October 1975 matchup in the Philippines with Frazier, Ali promised a Thrilla in Manila. It was all that and more—without a doubt one of the greatest boxing matches ever. Ali came out hoping to make quick work of Frazier and rocked him in the early rounds, but Frazier relentlessly bored in, frustrating Ali with his persistence. “You dumb chump, you!” Ali yelled at one point. At another he whispered during a clinch: “Old Joe Frazier, why, I thought you were washed up!”

Frazier had a response: “Somebody told you all wrong, pretty boy.”

In the middle rounds, Frazier gained the momentum as Ali seemed to tire in the hot, muggy air of Araneta Coliseum (which had been renamed Philippine Coliseum for the fight). But then Frazier wearied in the 10th, and Ali came on, pummeling Frazier’s face. By the end of the 14th round, one of Frazier’s eyes was swollen shut and the other was well on its way. As the fighters slumped on their stools before the start of what was to be the final round, both were badly beaten. In Frazier’s corner, trainer and manager Eddie Futch looked at his man, nearly blind with the swelling, and decided to stop the fight. Frazier protested, but Futch was resolute. Meanwhile, across the ring, Ali was asking Angelo Dundee to throw in the towel, but Dundee refused. Thus did Ali win the Thrilla in Manila. He responded by collapsing onto the canvas.

“It was like death,” Ali said after the fight. “Closest thing to dyin’ that I know of.” He also—finally, and very much too late—graciously acknowledged his bitter rival: “Joe Frazier, I’ll tell the world right now, brings out the best in me. I’m gonna tell ya, that’s one helluva man, and God bless him.”

IN THIS PERIOD, ALI HAD STARTED AN AFFAIR WITH AN actress from Louisiana, Veronica Porche, who had been one of four girls picked to help promote the Foreman fight. Although he and Porche initially tried to keep the relationship under wraps, in Manila they seemed to enjoy flaunting it. The following year, 1976, by which time Ali had already fathered a child with Porche, Ali’s wife, Khalilah, filed for divorce. And the year after that, Porche became Ali’s third spouse.

Having witnessed the brutality of Manila and the toll it took on both fighters, many observers of boxing, as well as people close to Ali, soon began to implore the champ to hang up the gloves. He found that he couldn’t. “Someone wrote that I stayed in the game too long and what I loved ended up destroying me,” Ali wrote years later in The Soul of a Butterfly. “But if I could do it all again, I would do it exactly the same. Whatever I suffered physically was worth what I have accomplished in life. My heart told me one thing and my mind told me another. And when I had to decide between them, I chose to follow my heart.”

Ali successfully defended his title a half-dozen times and then, in February 1978, at age 36, lost it in a split decision to Olympic gold medalist Leon Spinks. He regained the championship in a rematch seven months later, becoming the first pro heavyweight to twice reclaim a title, but his descent had begun in earnest. In 1980, after two years of inaction, he couldn’t answer the bell for the 11th round against former sparring partner Larry Holmes, and a year after that, on December 11, 1981, he lost a unanimous decision to Trevor Berbick. That fight was staged in a makeshift arena in the Bahamas after promoters could scarcely find a state in the U.S. that would allow it. The whole affair reeked of amateur hour; a cowbell was used to ring the rounds.

A month shy of a milestone birthday, Ali reflected on the ignominy of the Berbick affair and admitted at last what so many others had long been telling him. “Father Time caught up with me,” he said. “I’m finished. I’ve got to face the facts. For the first time, I could feel that I’m forty years old.

“We all lose sometimes. We all grow old.”

“AT NIGHT WHEN I GO TO BED, I ASK MYSELF, ‘IF I don’t wake up tomorrow, would I be proud of how I lived today?’” Ali wrote in The Soul of a Butterfly in 2004. “With that question in mind, I have tried to do as many good deeds as I can, whether it is standing up for my faith, signing an autograph, or simply shaking a person’s hand. I’m just trying to make people happy and get into heaven.”

That well describes how Ali approached life after boxing. It can be said that as long as he was physically able, he kept up a rigorous training schedule—but the exercises now were spiritual, the pursuits often holy. He became a goodwill ambassador for his religion and for his country, traveling the world on a platform of peace and generosity, inspiring the masses that swarmed whenever he touched ground, advising troubled youths, kissing the sick and doling out hugs and autographs from what seemed like a bottomless well of benevolence.

It is true that for most of Ali’s life after retiring from the ring, he was a sympathetic figure. In September 1984, he checked into Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City, concerned about feelings of fatigue, trembling in his hands and slurred speech (the last of which was an issue that doctors noted as early as the late 1970s). He kept up appearances for the press and his public, telling them that despite whatever rumors they had heard, “I’m still pretty, I’m still very pretty, and I’m still the greatest of all time.

“You know I’ve been out of the news in the boxing world for about four years,” he continued, “so I had to do something to get all you people to pay attention to me again—and it worked.”

Yet in truth, he arrived at Columbia-Presbyterian only after things had continued to deteriorate, as noted by various doctors, through the early 1980s. Ali’s neurologist at the hospital, Stanley Fahn, after being cleared by Ali to talk candidly with biographer Thomas Hauser, said that Ali had been diagnosed with parkinsonism—a neurological condition characterized by tremors, slow movement and muscle rigidity and commonly brought on by Parkinson’s disease. Fahn emphasized that Ali’s symptoms were strictly physical: “His condition did not affect his level of intelligence or the quickness of his mind.” (In his 2004 autobiography, Ali said that this was still the case: “My illness has not affected my ability to think and reason. I just move slower and speak softer and less often.” He also wrote movingly that, at first, he was self-conscious about his involuntary trembling and his faint voice, but, “after a while, I began to realize that how I handled my illness had an effect on other people suffering from Parkinson’s and other illnesses. Knowing that they counted on me gave me strength. And I realized again that I need people as much as they need me.”)

Fahn offered a conclusion already feared by many—that Ali’s condition was “due to injuries from fighting.” Later, another neurologist who cared for Ali would say that he felt the blame needed to be put on Parkinson’s disease rather than boxing. But whether or not blows to the head caused Ali’s condition, it was undeniably poignant to see a man who was once so vital and nimble of foot begin his slow march toward frailty.

In an aside, Fahn mentioned that Ali had been a model patient: “He went out of his way to be nice to everyone. Doctors, nurses, other patients, everybody absolutely fell in love with him.” No surprise there.

ALI’S MARRIAGE TO VERONICA, WITH WHOM HE had two children (including daughter Laila, who would become a boxing champ, ballroom dancer and television personality) was failing. Their divorce was finalized in 1986. That same year, Ali married again, for a fourth and final time. Lonnie Williams had grown up in Louisville across the street from the home of Ali’s parents and had first met Cassius Clay back in the early 1960s, when he was a voluble 20-year-old boxer and she was a shy five-year-old girl. It was a cherished story between them that while talking to a group of neighborhood kids, Ali put Lonnie on his lap (a moment that was visited earlier in this book). They became friends over the years, and now, all this time later, they wed.

Ali came to view his illness as divine intervention: God’s way of forcing him to reorganize his priorities at this new stage in his life. “It slowed me down and caused me to listen rather than talk,” he wrote. “Actually people pay more attention to me now because I don’t talk so much.” He listened intently not just to other people of substance—Ali moved easily among captains of industry and heads of state—but to the word of Islam. Gradually he had migrated from the teachings of Elijah Muhammad to those of traditional Sunni Islam, and his piety deepened. Where Ali once saw different races, he now perceived a greater humanity. His energy was focused on causes that ran the humanitarian gamut from children’s welfare to eliminating hunger to increasing oversight of boxing to promoting reading proficiency (especially among boys) to boosting awareness of Parkinson’s disease. Philanthropies around the world had Ali on speed dial, and whenever he could, he answered yes.

Millions who had once quarreled with this man by now had come to celebrate him. In 2005 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. Even more memorably, it was Ali who was chosen to light the Olympic flame at the Opening Ceremony of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. During those Games he was presented with a replacement of his boxing gold medal from the 1960 Olympics. He kissed the prize after it was hung around his neck. So many wounds had healed.

Of all the dozens of titles and awards conferred upon Ali in his later years, perhaps none signified the road he had traveled as much as his 1998 designation as a United Nations Messenger of Peace. Here was a champion of the most brutal, violent art being cited for his love of all mankind.

Ali, ever the Greatest, was acknowledged finally not for his physical talents, but for his very soul.

PHOTOGRAPH © HARRY BENSON 1978

Ali, not yet retired from the ring, at age 36.

CHRIS SMITH/POPPERFOTO/GETTY

WITH HIS SIGHTS ON FOREMAN, Ali first has to climb over Frazier. Above he chops wood in January 1974 at Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, during a training session for Frazier II. He wins that bout in a unanimous 12-round decision—12 rounds, because it’s a nontitle fight—in New York City. As mentioned earlier, there was concern for Ali’s safety when he accepted the Foreman challenge (and concern for his sanity, as well). As the fight was to be in Zaire, it would of course be called the Rumble in the Jungle. Certainly it was a big deal that African American gladiators of the magnitude of Foreman and, especially, Ali would be visiting the land of their ancestors. Here he is pictured being greeted by the throngs in downtown Kinshasa (below).

AP

BETTMANN/CORBIS

Ali and promoter Don King huddle in Ali’s villa in the days before the fight; on the wall is a portrait of Zaire’s ruler, Mobutu Sese Seko, whom Ali meets during the sojourn.

NEIL LEIFER/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Foreman is on the floor in the eighth round; the rope-a-dope technique has worked its magic. If there has ever been a more beautiful heavyweight boxer than Ali in his prime, it would be hard to name him. If there has ever been a savvier one than Ali in those predawn hours in Africa, it would be impossible to do so.

CO RENTMEESTER

BACK ON TOP, ALI PREPARES IN HIS rural redoubt to fight Joe Frazier a third time. This rubber match is slated for October 1, 1975, in the Philippines. As with the Fight of the Century and the Rumble, it is given a moniker even before it is staged: the Thrilla in Manila. The first bout’s nickname proved most apt. So did the second fight’s. Would this one?

CO RENTMEESTER

IN JULY 1975, ONLY WEEKS before heading for the Philippines to mix it up yet again with Joe Frazier, Ali brazenly struts across the airport tarmac in Boston accompanied by his brother, Rahaman; his wife, Khalilah; and Veronica Porche, the woman with whom he has begun an affair. After Ali sets up camp outside Manila for last-minute training and the prefight rituals—promotion, weigh-in, mouthing off—Khalilah learns not only of Ali’s extramarital dalliance but also that he has occasionally introduced Porche as his wife. She flies to the Philippines in a fury, greatly altering the casual gaiety that had graced what the press has dubbed the Ali Circus. (Khalilah’s divorce from Ali would become final a little more than a year later, with the ex-wife being awarded nearly $2 million in a settlement. Porche would become Ali’s third wife soon thereafter.) In contrast to the atmosphere in the Ali camp (at least, before Khalilah’s arrival), the mood in Frazier’s is intense and businesslike, fueled by aspiration and anger. The boxer knows that many feel he is through after the beating he suffered at Foreman’s hands, and he trains ruthlessly to prove them wrong—and to silence his great tormentor, Ali. If you ask fight fans today to name the greatest bouts of all time, the Thrilla in Manila will be on most lists. If you ask them their estimation of the most brutal fight ever, this one is often cited. It had one certain legacy and a second that can only be theorized. First, the ultraviolent back-and-forth action in the Philippines informed the choreography for the championship fight between Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed in Sylvester Stallone’s classic film, released a year after the Thrilla. And those who suspect that Ali’s late-career fighting contributed to his subsequent Parkinson’s cite this fight when detailing the punishment that the once-elusive boxer suffered in his thirties.

NEIL LEIFER/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Ali takes aim at Frazier’s left eye, and then, having prevailed in the fight by the barest possible margin, collapses off his chair (below).

AP

TERRY FINCHER/HULTON/GETTY

THE ADULT ALI LIVED IN MANY PLACES throughout his life—Kentucky, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Arizona, California. These two shots were taken in 1977 at the $700,000 house in Chicago. Like the man himself, the residence (below) was strong and impressive, and its interior décor (above) was colorful and extravagant—again, like the man himself.

TERRY FINCHER

TERRY FINCHER

At home with Veronica in March of ’77; the couple, already the parents of a baby girl named Hana, will wed in June. (It will be Hana who will assist her father in writing his memoirs.) In this photograph, Veronica is pregnant with their second daughter, who will be born in December and be named Laila. She will inherit much from her father—strength, grace and an instinct for boxing—and will, like him, become a bona fide American celebrity, even unto performing on Dancing With the Stars. Besides these two girls and the four children whom he fathered with Khalilah, Ali also had two other daughters, Miya and Khaliah, from extramarital relationships. Lastly, he adopted a son, Asaad, with his fourth and final wife, Lonnie. This last marriage was entered into on November 19, 1986, four months after Ali’s divorce from Veronica became final. Lonnie and Hana provided Ali with warm and needed support in his seniority as he coped with illness.

PHOTOGRAPH ©HARRY BENSON 1978

ALI RELAXES IN THE MASTER BEDROOM OF the Pennsylvania training camp during a break in 1978. By this point, the calls for him to retire were general, but he would not listen. Boxing was who he was, it was what he did: “Grass grows, birds fly, waves pound the sand. I beat people up.” But for how much longer could he?

©1978 GUNTHER/MPTVIMAGES

BASEBALL FANS ARE GENERALLY AGREED that Willie Mays stayed too long, and most boxing buffs feel the same way about Ali. He knocked out no one in the final five years of his career and lost three of his last four fights. The fatigue is evident as Ali sits during a title bout in Las Vegas on February 15, 1978, against Leon Spinks. Ali will lose his crown in a split decision this night, and though he will reclaim it by beating Spinks in a unanimous decision later in the year, he will lose another championship bout in 1980 to Larry Holmes (below). Then would come the travesty in the Bahamas against Trevor Berbick . . . and that was the end. It was a poignant, even sad final chapter to one of the great careers in the history of boxing—indeed, in the history of sport. The portrait of Ali opposite was made in Don King’s office in New York City after he had finally accepted retirement.

MANNY MILLAN/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

MICHAEL TIGHE/HULTON/GETTY

ON APRIL 24, 1982, THE YEAR AFTER HE left the fight game at nearly age 40, Ali takes his ease in Cannes, France. His Parkinson’s would not be diagnosed for another two years, but associates will later say that, in hindsight, there may well have been signs of the disease earlier.

RICHARD MELLOUL/SYGMA/CORBIS

WALTER IOOSS/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

WALTER IOOSS/SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

OF ALL OF ALI’S ABODES THROUGH THE YEARS, nowhere represented home to the extent that his farm in Berrien Springs, Michigan, did. He bought the spread in 1976 for $400,000, and it was his principal residence for more than two decades. These pictures show life on the farm in 1996: Ali continues to exercise regularly and prays to Allah five times daily. As his illness takes its toll, he will be unable to get down on his knees, but he will remain devout. His religious beliefs, guided now by Sunni Islam, have softened as they have deepened. They inform Ali’s extraordinary generosity; he says no very rarely, and his random acts of kindness are legion. One anecdote well illustrates his gentleness and sense of humanity. As Gene Kilroy, who worked for Ali, recounted it to biographer Thomas Hauser: He and Ali were visiting a nursing home one day, a characteristic endeavor. They were standing in the room of an elderly gentleman, and when a nurse asked the man if he knew who his special guest was, there was a glimmer of recognition. Then the man said, “Oh, my God; it’s Joe Louis. All my life I’ve wanted to meet you, Joe.” Kilroy laughed, but Ali nudged him to cut it out. Ali—who, we should remember, had been derided by Louis in the turbulent 1960s—told the man, “That’s right, I’m Joe Louis.” He gave the man a hug and said to him, “God bless you.” Kilroy said that Ali later told him: “All his life, that man has wanted to meet Joe Louis. Who knows how much longer he’s gonna live. But now he can die happy, knowing that he’s met his hero.”

©HAZEL HANKIN

SYMPATHY MAY HAVE PLAYED A ROLE IN ALI’S late-in-life rise as a beloved figure, but society’s reappraisal of this consistent man—the kind of person he long had been, the beliefs he had held for a half century—was more to the point. Ali’s good works only increased in his last decades, and the accolades and honors came, as we have mentioned earlier, from all corners. In 1999 he was named Sportsman of the Century by Sports Illustrated. In 2005 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for being “an inspirational figure to millions of people around the world.” Parks and streets were named after him, and often Ali attended the dedications; though ill, he was the opposite of a recluse and continued to travel the world, keeping company with kings. Above: In January 1996, as part of a humanitarian aid delegation from the United States that is delivering 10,000 pounds of medical supplies and medicine to the Cuban Red Cross, Ali shares a laugh with Cuba’s president, Fidel Castro.

V.J. LOVERO /SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Later that same year Ali thrills the crowd in Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Stadium—and so many more television viewers—when he is revealed as the ultimate torchbearer, the one who will light the cauldron’s flame, during the Olympic opening ceremony. As biographer Hauser wrote of the moment: “In all likelihood there has never been a time in the history of the Earth when 3 billion people felt love at the same time. But Ali made it happen.”

JOHN SOMMERS II/LANDOV

Back where it all began, in Louisville, Ali receives a hug from former President Bill Clinton during the November 19, 2005, gala grand opening of the Muhammad Ali Center at the Kentucky Center for the Arts. Looking on is another child of Louisville, Ali’s wife, Lonnie.

JASON REED/CORBIS

THE TORCHBEARER PASSES A TORCH: SUPER MIDDLE-weight champion Laila Ali receives a congratulatory kiss from her father after she has TKO’d Erin Toughill in round three of their June 11, 2005, title bout in Washington, D.C. At moments like this, surely his thoughts flew back to his own youth and vitality. With the help of his coauthor, Laila’s older sister Hana, he wrote movingly of such reflections in The Soul of a Butterfly. He smiled inwardly, recalling “Angelo’s shouts” and “the sparkle in Bundini’s eyes.” He summoned the days and nights of glory: “I recall the roaring of the crowd and the sound of the bell. I remember the feeling of the ring, the dancing, the shuffling, the rhythm, and my speed . . . As life moves forward I think of the pride of the crown; it all went by so quickly, like a sea of passing clouds. We have but a moment with youth, and although much has changed with time, I remember when I was king, and there are no sad goodbyes, only happy memories.”