“THEY DON’T PAY NOBODY TO BE HUMBLE!”

Football's Ego Problem

November 18, 2003, was a turning point in professional American football—perhaps in professional sport. Tampa Bay Buccaneer wide receiver Keyshawn Johnson was officially deactivated. Johnson had stated openly to his teammates during the year that he did not plan to be with the team at the end of the season. He felt that he was being underutilized and that the team was suffering because of that. There were many instances, in front of players and fans alike, where he let the coach know how he felt. Spokespersons for the team stated that Johnson was let go because he was a distraction to the team. He had been missing training sessions and team meetings and was not shy about showing his disgust for his coach, Jon Gruden.

Why was this event such a turning point in professional football? What is so significant about Johnson's deactivation? Players, fans, and owners are coming belatedly to learn what the best coaches have always known: self-absorbed or ego-puffed players, however talented, are in the long haul a detriment to their team. Johnson's deactivation was a signal to the rest of the league and to all of sport that at least one team thinks it is easier to win consistently without such players, however gifted. The underlying premise is this: A team of talented players—who are committed to their coach, their fellow players, a system of team play, their sport, and their fans—will generally outperform a team of superstars, each of whom is chiefly committed to himself.

This argument against self-absorption is forceful, yet it does not go far enough. Players do not harm their team merely through fewer wins and more losses over time. Some players also harm their sport, their society, and even, perhaps unknowingly, themselves. To aid in seeing the weight of this problem, in what follows I phrase the difficulty not just in terms of self-absorption but also in terms of other-concern: Why is it that so many athletes have such a barefaced disregard for others—players, coaches, and fans—in professional football today?

Ego-Puffing

Perhaps a large contributing cause of this problem is the manner in which players are marketed before they make it to the professional ranks. They are scouted and assessed principally as individuals, not so much as members of a team. Too often we assume that raw talent and athletic potential will make a player a factor at the next level. When players turn professional, the lure of a multimillion-dollar salary entices them to market themselves as individuals, not as members of a team. A talented wide receiver like Johnson is attractive to a contending team in need of receivers. Unfortunately, those fishing for talent seem seldom to consider whether such players will be an asset or a distraction to the team in the long haul.

Playing on and for a team is important, but increasingly players strive to make themselves visible in team sports through ego-puffed displays: self-promoting exceptional play, showboating, taunting, and even fighting opponents, coaches, or teammates. What is most unsettling is that players are generally praised, even rewarded, by fans for drawing attention to themselves at the expense of their opponents and even their teammates and coaches. When things are going well for the team, ego-puffed players are the first to let everyone know just how their play has led to such success. When things are going badly, it is, of course, not they who are to blame. Football analyst and former player Merril Hoge had this to say about Johnson, before his deactivation from Tampa Bay: “Oftentimes, it's during adversity that you find out what a person is truly made of. And, true to character, when something doesn't go right, Keyshawn Johnson has repeatedly been the first guy to beat his chest and say, ‘What about me?’ In the midst of a three-game skid, what the Bucs players should be saying is, ‘What about the team?’” 1

The narcissistic antics of self-absorbed athletes in football exist because we not only tolerate them but also encourage them. As football fans and fans of competitive sport, we eat up ego-puffed athletes.

Sensationalism and Other-Concern

What of Terrell Owens, perhaps today's most celebrated ego-puffed athlete not only in football, but in American sports? Owens seems to love football, and his showy displays suggest that he has a certain amount of fun competing. Still, after a series of episodes that were deemed harmful to the team, he was released in 2006 from the Philadelphia Eagles, only to be picked up by Dallas the following year.

Ego-puffing may be fun for athletes like Owens, and it may have a great deal of fan appeal; nonetheless it is wrong for competitive sport. First, ego-puffing always undermines the efforts of teammates and the rest of the supporting cast (from owners and coaches to trainers and boosters). For instance, after being sidelined with a broken leg toward the end of the 2005 season, Owens made these comments about the Philadelphia Eagles’ chances of making it to the Super Bowl without him:

It hurts bad just to hear how now people are walking around town saying, “We're done.” or “Without T.O., they can't get it done.” Everybody knows they have to step up. There's no ifs, ands or buts about it. What I brought to this team—on and off the field—through 13, 14 games …that's enough to take them, to get over the hump. That will take them to the NFC Championship. I honestly believe this team will win the NFC Championship once we get there. There's no doubt in my mind. I feel like I've done what I had to do. I've set the table. Now all they have to do is go eat.2

The implication of the last sentence is plain: Owens has done the dirty work for the team through some thirteen or fourteen games; now it is “their” turn to do the rest, and the rest is easy. Just sit and eat. Owens has set the table. The contrast between his use of “I” and “they” throughout suggests that he has set himself apart from, or is above, the team. Only once does he use the word “we.”

Second, self-promotion makes light of the efforts of opponents. One has only to consider the 2002 episode of Owens's autographing the ball after a touchdown against the Seattle Seahawks. Seattle's coach Mike Holmgren said afterward, “I think it's shameful. There's no place for anything like that in our game. It's too great of a game.” Holmgren then added that one of his ballplayers should have confronted Owens. “I think certain times players cross the line, and you've got to take care of business.”3 The incident shows that self-promotion and other-deprecation are related issues. It is virtually impossible to puff yourself up without deflating opponents.

On the self-absorption of Owens, Paul Willistein writes: “While we enjoy Terrell Owens’ athletic acumen, do we really need post-game analysis of his sideline [antics] and Desperate Housewives TV commercial antics? Based on the amount of newspaper ink and commentators’ air time, Owens symbolizes the triumph of team member over team.”4 Owens's “triumph” is difficult to swallow, since he has not done for football what, say, Babe Ruth did for baseball or Ali did for boxing. As the implications of his career unfold, both for himself and his sport, his triumph may very well turn out to be Pyrrhic.

Why do sports fans, coaches, players, and owners not only tolerate, but also encourage, ego-puffing in athletes? Part of the answer is the sensationalism of competitive sport and the natural human tendency to be drawn toward sensational events. According to philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952), a sensationalist attitude is oversimplified and anti-intellectual—one that takes episodes out of their proper context and fails to see them in relation to other things. Writes he: “One effect [of sensationalism] …has been to create in a large number of persons an appetite for the momentary ‘thrills’ caused by impacts that stimulate nerve endings but whose connections with cerebral functions are broken. Then stimulation and excitation are not so ordered that intelligence is produced. At the same time the habit of using judgment is weakened by the habit of depending on external stimuli. Upon the whole it is probably a tribute to the powers of endurance of human nature that the consequences are not more serious than they are.”5

The effect of sensationalism is the abandonment of what Dewey calls an “intellectual” approach to events—here competitive sporting events—for a momentary, thrill-seeking approach to them. People prefer the sudden jolt of episodic thrills that sporting events offer—being unexpectedly blown away by a gargantuan home run or by a basketball slam-dunk—to a fuller and richer grasp of athletic competitions, within the larger context of other events. We are moved more by Owens's 2002 ego-puffed signing of the football after a touchdown than by the concerted effort of his team that allowed the catch to happen (the strong play by the defense that enabled the offense to get the ball, the solid blocking by the offensive line, the quarterback's precise throw, the other receivers who blocked or acted as decoys, etc.). Ego-puffing is the bastard child of sensationalism, because it promotes further sensationalism at the expense of a fuller grasp of what is going on in a contest. One puffs up oneself and, at the same time, deflates others.

After Owens was released from the Eagles at the end of the 2005–2006 season, former teammate N. D. Kalu had this to say: “What did I learn from it? That the chemistry thing is real. I never was one to believe in chemistry, but you had to notice that we'd always brought in the same kind of guys, guys who didn't care about the spotlight or about stats, guys that just wanted to win. You bring in one guy who doesn't feed into that thinking and it disrupts the whole team.”6

Individual Statistics and the Lack of Genuine Concern for Others

Another reason why ego-puffing and lack of other-concern are such problems in contemporary competitive sport is our modern-day preoccupation with statistical analysis in all aspects of competitive sport—a concern that is especially evident in fantasy football. Today there is not just victory, but categories of victory, where statistical components come into play. For example, many sports fans know that Texas beat Michigan in the 2005 Rose Bowl, 38–37, in a drama-filled game, but the more enlightened mavens know that sixteen Rose Bowl records were tied or broken in the process. Of these, some of the more noteworthy are as follows:

- Texas quarterback Vince Young was responsible for five touchdowns (four rushing, one passing; ties record)

- Young also rushed for 192 yards and four touchdowns (new record, quarterback)

- Michigan receiver and kick returner Steve Breaston had 315 all-purpose yards (new record)

- Breaston also had 221 kickoff return yards (a record for all bowl games)

- Michigan quarterback Chad Henne passed for four touchdown passes (ties record)

- Michigan All-American receiver Braylon Edwards caught three touchdown passes (new record)

- Michigan scored the most points scored in a losing effort (ties record)

In short, an after-the-game statistical analysis of the 2005 Rose Bowl reveals that there are numerous contests within a single contest and even the losing team can claim its share of victories. Henne, Breaston, and Edwards, in a losing effort, did what they did in front of a national audience and a multitude of NFL scouts. With great individual performances, they also became part of college football history. The Wolverines may have lost the war, but they won a good number of battles along the way.

Why is there such an obsession with numbers in competitive sport today? Bero Rigauer says that numbers give sport objectivity.

Athletic achievements now take place in the “objective framework” of the c-g-s (centimeter, gram, second) system or in point scores which rely either upon objectively measurable achievements (as in the pentathlon and decathlon) or in referees’ calls and subjective judgments (as in team games, gymnastics, boxing, etc.). The application of a socially sanctioned system of measurements allows the objective comparison of all athletic achievements—exactly like the achievements of labor productivity. They are all rationalized into universally understandable measurements of value. With such quantified, abstract forms, it is possible to compete even against opponents who are not present. One may race, for example, against a world record.7

Statistical analysis allows us to rank athletic performance on an absolute scale, and absolutism gives athletic competition legitimacy. Michigan's Steve Breaston's 315 all-purpose yards beat the former record of O. J. Simpson (276 yards in 1969), and that put him “on the map.” That is legitimacy.

Of course, numbers related to competition are themselves neither good nor bad. Some seem interesting for their own sake. Michigan and Texas were deserving of their Rose Bowl matchup, among other things, because they are two of the most winning programs in college football—with 842 and 787 wins respectively at the time. This shows that both schools have football programs, steeped in tradition, with commitments to winning football games. Other statistics, like Michigan's tying the record for most points scored in a losing effort, seem insipid. Nonetheless, the 2005 Rose Bowl is an illustration of today's frenzied application of numbers to competitive sport. There are various games we can play with numbers before, during, or after a contest for self-amusement. There are various games within a game.

This application of numbers to competitive sport has one ugly consequence. Far too often players are evaluated by statistical data that function to pull them outside the framework of the team or the sport they play. Statistical data focus on players as individuals, and that has a marked impact on their team or their sport. Certain players, usually the most insecure, become ego-puffed because of the numbers that “prove” their superiority. Like leeches on flesh, ego-puffed players feed off numerical analysis to the extent that they care more for their own numbers than for their team or sport.

One of the most notorious present-day examples of ego-puffing is football star “Neon” Deion Sanders (a.k.a. “Prime Time”).8 One of the most talented defensive backs ever to play in the NFL, Sanders is also one of the showiest. As a senior at Florida State, he arrived at FSU's stadium for a game against the University of Florida in a limousine, dressed in a tuxedo. Exiting the limousine, he said, “How do you think defensive backs get attention? They don't pay nobody to be humble!” This ostentation he took to Major League Baseball and to the NFL, where he has had unquestioned success as a defensive back and kick and punt returner. Sanders has never been shy about letting others know about his greatness.

Over time, the flashy jewelry and clothes, fine cars, and other byproducts of his competitive successes took a toll on Sanders. Despite Super Bowl victories with Dallas and San Francisco, difficulties in his personal life led him to attempt suicide in 1997. He then found meaning, as he tells the story, by turning away from Deion toward Christ. “I'll have to be honest. I never liked Deion Sanders. Too much of a showboat for me. Now I'm going to spend eternity with him because he is trusting in Christ.”9

Why do coaches, owners, players, and fans tolerate such self-centered arrogance? One has merely to look as Sanders's numbers over his career as a defensive back and punt and kick returner. Those numbers, it seems, justify the self-absorption and give Sanders, whether his team wins or loses, legitimacy.

Aretism: An Ideal for Competitive Sport

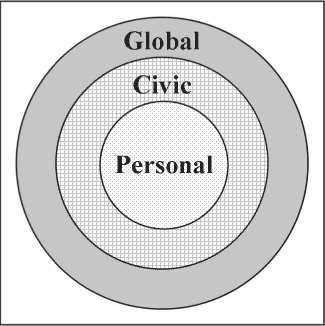

In several sport-related publications, I have sketched a normative and integrative account of competitive sport called “Aretism.”10 I have argued that Aretism commits athletes to threefold excellence: (1) excellence through personal integration; (2) excellence through civic integration; and (3) excellence through a type of global integration.

Personal integration involves athletes’ own autonomous striving for a greater sense of self through competitive sport. Through integrative participation, athletes come to see sport as a vehicle for both physical and even moral self-improvement.

Civic integration implies that athletes are citizens of a competitive community in which they treat sport as a social institution and they recognize and respect others while competing.11 While competitively and creatively distinguishing themselves from others in a particular sport, athletes acknowledge the contributions of other athletes, who also accept sport as a social institution. Civically integrated athletes agree to conduct themselves in a manner respectful and appreciative of the efforts of other competitors. In short, following the dictum of the philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), others are to be treated as ends and not means.

Finally, global integration entails deliberately engaging in competitive sport in a manner consistent with the set of relatively stable values that define its practice over time, such as friendliness, patience, perseverance, and commitment.12 Athletes come to understand that their own athletic expression in sport, as a celebration of human perseverance and creativity, takes on meaning because of these global values. Thus, through global integration, individual competition merges with moral responsibility, and individual autonomy is thereby suitably nurtured. In a word, global integration requires that athletes are answerable to, not freed from, the dictates of justice.

In short, because of its regard for people as social animals and sport as a social institution, Aretism places normative constraints on athletic competitors.

How is Aretic integration best grasped? It is helpful to think of concentric circles. Beginning with personal integration in the centermost position, there follows civic integration and, finally, global integration. The overall system owes much to Stoic philosophy, a school of thought that thrived in Greco-Roman antiquity.13

In what follows, I attempt to flesh out Aretism as a modified version of Stoic ethics. The idea here is to give not just an ethics of sport, but an ethics of life that is respectful of competitive sport as a valued social practice.

Stoic Balance: Ethics for Sport and Life

The Stoic philosopher Chrysippus (280–207 B.C.) speaks of virtuous activity in life as a competitive footrace: “When a man enters the footrace …it is his duty to put forth all his strength and strive with all his might to win, but he ought never with his foot to trip or with his hand to foul a competitor. Thus, in the stadium of life, it is not unfair for anyone to seek to obtain what is needful for his own advantage, but he has no right to wrest it from his neighbor.”14 For Chrysippus, virtue entails that one may compete for the first prize in life, so long as one does not trip or shove competitors along the way. This is, in effect, the Stoic notion of oikeiosis.

Oikeiosis for the Stoics was a matter of achieving a balance between self- and other-concern in life.15 One strives to help others but does not need to sacrifice completely one's own interest to do so. In all actions, even other-regarding actions, one's own interest must be considered too, because one is as much a part of the cosmos as is any other person. In other words, one's own interest impacts the interests of others. One must not, however, secure one's own interest to the detriment of another. Cicero states it thus: “For one person to deprive another in order to increase their welfare at the cost of the other person's welfare is more contrary to Nature than death, poverty, pain, or any other thing that can happen to one's body or one's external possessions. To begin, it destroys human communal living and human society. If we are each about to plunder and carry off another's goods for the sake of our own, then that will necessarily destroy the thing that is in fact most according to Nature—namely the social life of human beings.”16

Yet oikeiosis for Stoics is more than just a matter of respectful competition with others, where “respect” is cashed out as refusal to harm another while competing. It embraces Stoic egalitarianism, other-concern, and global culpability. Virtue through oikeiosis implies that one knows fully well what is one's own and what is not one's own—that is, what is another's—and that seems a clear statement not only of self- and other-knowing but also of self- and other-concern. The virtuous athlete competes to the best of his ability, but he does so with full respect for himself, other competitors, and the sport that he plays.

“In the Moral Zone”

How would an athlete who is committed to respectful, Aretic competition behave? He would behave no differently than one who is committed to respectful living. Again, I return to the ancient Stoics to explain.

The ancient Stoics thought not only that a person could progress toward virtue but also that a person could attain perfect virtue—a stable state of soul that lent itself to flawless living. The best way to understand this perfection of soul, Stoic sagacity, is by analogy with an athlete in the zone.

Athletes who have experienced being in the zone typically speak of complete immersion in the game, things slowing down, effortless play, freedom from distractions, extreme confidence in their capacities, and lack of deliberation while competing. Similarly, what Stoics describe when they describe a sage seems to be a type of being in a moral zone. The chief difference is this. Most consider athletic zoning to be a phenomenon that may last from a few minutes to a few days. Stoic sagacity is considered to be a lasting state of soul—a way of life. Once a sage, a Stoic is “in the moral zone,” as it were, if not for life, then for a lengthy period of time.17 This would be comparable to the impossible scenario of an athlete finding his zone one day and then not leaving it.

What I have sketched above is a model of moral zoning that is characteristic of Stoic sagacity. Yet this model also applies well to Aretic activity in competitive sport. The following rules characterize the model during competition (whether inside or outside competitive sport):

1. Harm no one.

2. Preserve the common utility.

3. Hold what is one's own as one's own and let others do the same.

4. Strive only for advantageous things within one's reach and outside the reach of others.

5. Fulfill oneself to the best of one's capacity, through knowledge of self and others.

This model, when fully fleshed out as a child of Stoic ethical thinking, has one startling feature that may not be obvious. Unlike sporting contests, like football games, where ultimately only one team can win, in the contest of life there is no such constraint. If anything, Stoic sagacity entails that the contest will be better the more winners it produces. So according to the rules of the contest, mutual assistance is morally desirable, and that is a strange sort of contest!

How do we make sense of life as a contest where as many people win as is possible? Such a contest begins with self-understanding—that is, knowledge of what is one's own and what is not one's own. The right sort of upbringing will help a youth to learn about himself, what he can and cannot do, in spite of his desires. It will also help him to hone his reasoning skills, so that he will know how to adapt himself uniquely to ever-changing circumstances each day. With careful nurture, he will develop discernment of his circumstances and a clear grasp of his capacities, and he will not strive for what is beyond his reach. The Stoic Epictetus gives a helpful analogy in his Handbook. At a banquet, a virtuous person does not call out or stretch out his hand for food. Instead, he waits for it to come to him, and, when it does, he takes what he wants and passes it immediately to the next person, so that he too may have his share.18 In the analogy, one merely acts to the best of one's capacities in circumstances, and, when one cannot help others, one allows sufficient space for others to act to the best of their capacities. That is accepting one's role in life. That is oikeiosis. That is what it means to play by the rules of the game of life.

There are, of course, limits to this moral-zoning model. Perfection in life, like perfection in sport, is an unreachable ideal. Aretism, grasped as a tripartite ethical theory, rejects Stoic perfectionism in favor of progressivism. If the perfectionist ideal of canonical Stoicism is continued peak performance through always performing right acts, the Aretic progressivist ideal is peak performance as often as possible through the greatest possible proportion of right acts to non-right acts. A “competitor” in life is rewarded most not only for immersing himself in the contest of life but also for helping to immerse all other competitors in the contest of life as much as he can. Fullest immersion in the contest of life is striving to one's fullest ability to hit the target at which one, striving to live virtuously, aims. Consistent with canonical Stoicism, winning the contest is not a matter of hitting the target but of right-intended action aimed at hitting the target.19 Right-intended action is winning. In a similar fashion, what is true of right living is equally true of good athletic competition.

Conclusion: Aretism and American Football

How then does Aretism attempt to solve the problems of ego-puffing and lack of other-concern in competitive sports—most notably American football? First, it is important to call attention to them not only as genuine problems in today's competitive sports but also as problems of significant moral weight. Next, I have tried to show that competition itself is not the cause of these problems, though excessive competitiveness and sensationalism are certainly causal factors. Finally, I have argued that Aretism—understood as a progressivist ideal for competitive sport that is modeled after early Stoic ethical thinking—allows for a virtue-based way of dealing with ego-puffing and other-concern in a manner that is true to the spirit of competition and respectful of competitive sport as a valued social practice.

Notes

1. “Johnson's Time in Tampa Appears Over,” ESPN.com, 20 November 2003; http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/news/story?id=1664796.

2. This quote was formerly on Terrell Owens's Web site and is no longer available.

3. The incident was widely commented upon in the press; the quotes here were found at http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4155/is_20021020/ai_n12488126.

4. Paul Willistein, “‘Basketbrawl’ Epitomizes Pro Sports’ ‘Slam Dunk’ Non-Team-Player Mentality,” East Penn Press (Allentown, PA), 8 December 2004, 18.

5. John Dewey, Freedom and Culture (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1989), 39–40.

6. Dana Pennett O’Neil, “At Season's End, Several Eagles Come Clean about Terrell Owens,” Philadelphia Daily News, 5 January 2005.

7. Bero Rigauer, Sport and Work, trans. Allan Guttman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 57–58.

8. Sanders often notes with pride that he gave himself both nicknames.

9. “Where Sanders Goes, Teams Win,” ESPN.com, http://espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00016459.html; accessed 10 January 2008.

10. M. Andrew Holowchak, “Excellence as Athletic Ideal: Autonomy, Morality, and Competitive Sport,” International Journal of Applied Philosophy 15, no. 1 (2001): 153–64; “‘Aretism’ and Pharmacological Ergogenic Aids in Sport: Taking a Shot at Steroids,” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 27, no. 1 (October 2000): 35–50.

11. “Political” in “Excellence as Athletic Ideal.”

12. “Cosmic” in “Excellence as Athletic Ideal.”

13. The model I propose is Stoic and resembles that of Hierokles’ ten concentric circles. Hierokles writes: “The first and closest circle is the one that a person has drawn as though around a center, his own mind. This circle encloses the body and anything taken for the sake of the body. It is virtually the smallest circle and it almost touches the center itself. Next, the second one, further removed from the center but enclosing the first circle, contains parents, siblings, wife, and children. The third one has in it uncles and aunts, grandparents, nephews, nieces, and cousins. The next circle (4) includes the other relatives, and this is followed by (5) the circle of local residents, then (6) the circle of fellow-demes-men, next (7) that of fellow-citizens, and then (8) in the same way the circle of people from neighboring towns, and (9) the circle of fellow-countrymen. The outermost and largest circle (10), which encompasses all the rest, is that of the whole human race.” Stobaeus, Florilegium, vol. 4, ed. C. Wachsmuth and O. Hense (Berlin: Weidmannos, 1884–1912), 671.

14. Cicero, Duties, 3.10.42. My translations throughout.

15. Literally, the process by which things are rendered familiar to oneself or one's own. Humans have a natural impulse to pursue what is appropriate to their own nature and shun what is not. When I refer to oikeiosis here, I am referring to what is most rightly one's own as a fully rational, adult human being.

16. Cicero, Duties, 3.5.21.

17. Allowing for the possibility that virtue can be lost, once gained. The Stoic Cleanthes believed that virtue, once secured, could not be lost. And so, wisdom, once secured, was the continual exercise of virtue. Chrysippus thought that even a sage had to be on guard, as drunkenness or forlornness could cause one to slip from virtue. Diogenes Laertius, Lives, Teachings, and Sayings of Famous Philosophers, 7.127–8.

18. Epictetus, Handbook, 15.

19. Cicero, Ends, 3.6.22.