Why do I have problems working up a satisfactory finished picture from an exciting sketchbook study?

Racing home, we rounded the bend. Suddenly, before us was the most lovely subject for a painting. We quickly parked. Time was limited, so out with the sketchbook, and I made a hasty study in pencil with just the essential details – a little tonal shading and a few colour notes. I took a photograph and jumped back in the car and we carried on with our journey.

Winter Scene

15 × 20.5 cm (6 × 8 in)

It was a dull, rainy day. I sketched from the car and there was little tonal contrast. It all seemed very unpromising but my sketch (right) became a challenge. I tried to compensate for the narrow tonal range and emphasized any local colour. Above all, I stopped while the painting still had the ‘sketchbook feeling’.

Some time later, back in the studio, I used my sketch as a reference to complete a successful watercolour painting that exactly portrayed my impression of what I had seen.

Or did I? In fact, it is most unlikely! In the ideal world this is what is expected; after all, Turner produced some stunning watercolour paintings based on little spidery sketches. He travelled on horseback without the company of a state-of-the-art camera. So why is it so difficult? What is the missing link?

This is the dilemma. How often have I heard a fellow artist say that they were pleased with their sketch, but disappointed with the finished painting. I have had many long and intriguing discussions about the problems that arise when working up a successful painting from a promising sketch. These problems can occur either in the studio after the sketch has been made, or outside when a sketch has been used as a preliminary to the painting.

I do not believe that the basic problem lies in how the sketch itself is made. Whether it is a thumbnail sketch, a detailed line drawing, a tonal study or even a little painting, there seem to be many pitfalls before the final painting is produced. The problem seems to lie in how the sketch is used to produce the painting.

Hidden Treasure

32 × 48 cm (121/2 × 19 in)

What an irresistible subject! But I was careful in the way I painted it. The sketchbook enabled me to choose the angle I liked. As in Winter Scene, the light was so poor that a photograph was impossible, and my sketches were invaluable.

The first question to ask yourself is whether the subject is right for a finished painting. Some people might think that a particular subject is ideal for a sketchbook study but there is not enough ‘weight’ in it for a finished painting. The magical thing about being an artist is that there are no rules. The illustrations here show the sketch and final painting of a winter scene. I framed it like this because I felt I had finished it, even though there was not a great deal of content. I did not really have any more to say and hoped I had caught the essence of the subject. But what was most important was that this picture still had the ‘sketchbook feeling’ about it.

Is the ‘sketchbook feeling’ the missing link? What is it about an artist’s sketchbook that we all love? I have often watched artists demonstrate at our local art society. Usually they bring along a few of their finished framed pictures and then generously pass round their sketchbooks while doing the demonstration. Somehow, the sketchbooks never get very far round the room because someone in the audience becomes totally absorbed in it.

Why is it that the sketchbook is so fascinating? So often it is full of life and vigour and a sense of spontaneity, which is sometimes lacking in the framed work. Also it is a ‘private’ thing. A sketchbook is for the artist’s use. Generally it is not intended for public scrutiny, so there is a personal feeling about it. It is these qualities of spontaneity and ‘personal’ experience that you should strive to hold onto in the finished work.

Having decided that you would like to use your sketch as the basis for a watercolour painting you then need to decide what size of paper would be best. If the sketch sits comfortably on the page it is probably useful to use a piece of paper for the finished work that is of the same proportions as the pages of the sketchbook. This seems obvious, but it does help!

As regards the size of paper, as ever, there are no rules. I suggest that you envisage the final picture and imagine what would look best. A detailed sketch of a busy street scene can look charming as a small picture, whereas a simple expansive beach subject might be perfect on a grand scale where the brushstrokes can be bold.

Sarah and Barbara Painting Florence

24 × 29 cm (91/2 × 111/2 in)

I had intended to depict the wonderful panorama of Florence. But who could resist concentrating on my friends, settled in the grass? I realized from my sketch that I needed to change the emphasis of the painting.

I came across the subject for the painting Hidden Treasure (opposite) a few miles from home. An old Jaguar car was well hidden in the foliage. I was a bit worried that the subject was rather whimsical and I was most anxious not to make it too pretty or ‘greetings cardish’. Although the light was poor and it was a little boggy underfoot I hoped that I would have time to do the painting on site.

I made a few sketches of the car and trees from different viewpoints. On this occasion I was using the sketchbook to investigate different compositions rather than with the intention of preparing a subject to work into a finished painting in the studio. The sketches would also be useful if interrupted during my painting.

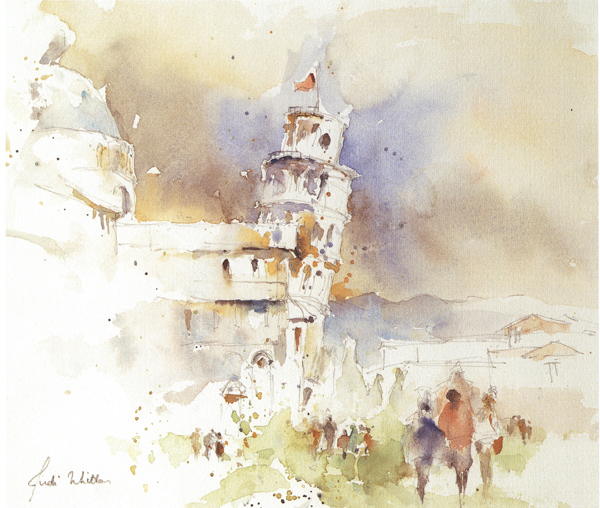

Pisa

21.5 × 26 cm (81/2 × 101/4 in)

I tried to keep ‘fresh eyes’ as I looked at this familiar place. The sketch needed to be accurate and it helped to incorporate the movement of people into the composition.

By walking around the car and sketching I was both studying the subject and thinking about how to paint it. (I took a photograph, too, but when I looked at it later it was totally useless as the car was completely hidden in the shadows.) I was most anxious to convey the impression that the trees and car had become ‘one’ and to keep a lively feel to the foliage. I tried hard not to overwork the painting, and this is where sketches can help to form your ideas at the beginning.

In Sarah and Barbara Painting Florence on my sketchbook was invaluable. I was painting in Italy with my friends. After problems with onlookers I had tucked myself away in a quiet spot. We were in the Boboli Gardens overlooking Florence and the weather was showery. My friends settled down on the grass. They were much farther apart than shown in the painting and I used the sketchbook to bring them closer together and to position them sympathetically with the panorama in front of us. I had originally intended to concentrate on the wonderful view of Florence, but I could soon see from my sketch that my friends were the most important part of the painting! In addition to this the sketch also became my insurance policy in case my friends moved position, or the threatening rains arrived.

Churchyard, Stow on the Wold

38 × 43 cm (15 × 17 in)

This was painted on the spot with no preliminary sketch. I wonder if it would have gained or lost had I done one?

The leaning tower of Pisa (opposite) is so well known that it is difficult to keep the spirit of the place and to paint it as if you are looking at it for the first time. Also I had to ‘edit’ extensive ‘rescue’ works around the base of the building. It was hard not to exaggerate the ‘lean’ on the tower. In this case the sketch needed to be accurate as well as conveying the beauty of this exquisite structure. It was interesting to observe that the flagpole on top of the tower was vertical. Here the sketchbook was useful, too, to record the people and incorporate them into the study, rather than make them look as if they were an afterthought.

The painting of the Churchyard, Stow on the Wold (above) is included here even though I decided to make no preliminary sketch for it. I looked at the subject for some time and made decisions, and then just painted it. Sometimes I prefer not to give any concentration to the sketch and save all my resources for the painting. Bearing in mind the expression ‘analysis leads to paralysis’, I worry sometimes about the slight risk of over-preparing for a painting and going a bit stale, especially as watercolours often benefit from a feeling of spontaneity. But there is no substitute for doing a lot of thinking before and during the painting.

From these experiences I have tried to learn the best way of interpreting sketchbook studies. The major problems have arisen when my sketch looked very acceptable and I have simply used it to complete the finished work without ever establishing what the sketch was really about. Somehow, these pictures lack vitality. Although considerations such as composition, tonal balance and colour relationships are important in all work, it is the feeling that the painting evokes that makes it special.

To summarise: there are no rules. If you like your sketch, think about what it is that you like most. Extract the essence, and keep that idea uppermost in your mind as you tackle the painting. When you feel you have ‘said it’, it is time to stop.