How do I make my boat and harbour scenes look more convincing?

For many artists there is nothing more inspiring than sketching or painting in a bustling harbour. It is also one of my favourite subjects to paint. So why do many painters find the subject so difficult?

Perhaps it is because harbours hold so much subject material in such a confined space. A jumble of buildings, boats, people, mud, water, and much more, is a lot to take in and can be confusing at first sight. Another problem is the tide; the whole scene can change completely in a matter of minutes. Many students seem to find drawing boats difficult, too, and the thought of groups of tourists peering over their shoulder can be a daunting one – particularly if they have never drawn a boat before. ‘I can’t draw boats ’ is something I frequently hear on my courses.

Quayside, Looe

26.5 × 36.5 cm (101/2 × 141/2 in)

Here I particularly liked the contrast of sand, still reflections and moving water, with the tide on the turn. I added some of the highlights using white gouache. Remember, light boats reflect darker and vice versa.

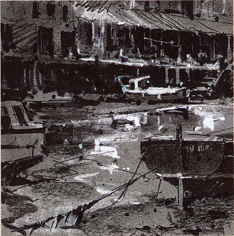

Low Tide, St Ives

26.5 × 36.5 cm (101/2 × 141/2 in)

This painting of the harbour at St Ives, Cornwall, was done from a sketch and photograph. St Ives is all about light, so here the sky in the painting plays a big part. The verticals – the lighthouse and masts on the boats – are also important as they link the sky to the landscape.

The reasons are numerous, but many students have never even tried to draw boats. Many feel nervous because they know nothing about them. However, drawing and painting boats well does not mean that you have to fully understand their construction, though it helps if you have a little knowledge, or certainly an interest in the subject.

We tend to draw what we know from experience, rather than what we see with our eyes. Therefore, observing both objectively and analytically is something you must learn to do if you wish to improve your marine scenes. More often than not, boats are the focal point of a painting; it is important they are accurately portrayed, or at least look seaworthy. That does not necessarily mean adding more detail. What you leave out is often more important than what you put in.

The materials you choose for sketching will depend on your own preferences. Mine consist of an A3 cartridge pad, black felt-tip pens, charcoal and Conté crayon. I also use a smaller A4 landscape sketchbook for watercolour as well as tinted pastel paper (stretched) for watercolour and gouache.

There are no short cuts to drawing boats; it is a case of measuring and checking relative heights and widths and making constant comparisons of proportions. I find boats more interesting when they are viewed in three dimensions; that is, where the viewpoint is such that the length, width and depth of the boat can all be seen. However, I often like the simpler, two-dimensional view, which may be the boat side-on, or perhaps looking from the bow or stern.

Boats can be a real problem if the tide is in and they are moving about in the water. But do not let that put you off; just decide on the best position of the boat, be patient and work quickly. Remember, though, the chances are that it could be taken out on a fishing trip at any time!

Many of my paintings are done at low tide. This is for a number of reasons, the most obvious being that the boats do not move around. But I also find that the whole structure is visually far more interesting. When they are tilted on the mud, as in Low Tide, St Ives, their masts create further compositional interest. I also find that low tide can create far more interesting shapes and contrasts than high water. Tidepools, seaweed, ropes and rusting chains can be exciting elements in a painting, of which Polperro Harbour on is a good example.

Making boats ‘sit’ on the mud, or float on the water is another common problem. Many students do not make the shadows, or reflections, quite dark enough, so that boats ‘float’ in mid air. With watercolour I often merge a wet-into-wet wash of the keel into the sand or water, making it difficult to distinguish between the two.

Photograph of Polperro Harbour

Choosing your viewpoint and your eye level is very important. You will find boats viewed from the quayside, where you have to look down on them, quite difficult as you will have to consider perspective and foreshortening.

Let us imagine you are on one of my painting courses and we go together to the picturesque harbour of Polperro, in Cornwall. Take a look at the photo above. This complicated harbour scene is typical, and shows the many problems you could be faced with. It is rare to find a perfect ready-made scene – you have to create one for yourself. There are many options and permutations in every scene and, in fact, you will never exhaust the endless possibilities.

To see what I mean, have a look at the examples here, where I have arranged the elements in each picture in order to make a composition that works, based on the view above. Most marine subjects are painted in a landscape format, because this creates a sense of openness. But do not necessarily go for the obvious. You may find that a portrait, a square, or even a long narrow format is more challenging and works much better. To simplify the scene, I used three boats in each of the examples.

Do not be too ambitious; look for something that ‘excites’ you. Start with something simple – an interesting boat, the play of light on the quay, the reflections in a tidepool. Like the photograph, our eyes take in this broader view, full of buildings, boats and lots of detail. You may find working from photographs difficult as they record everything – it is the inspiration that you will need. This view in the picture above is made more difficult because the sun is behind us and everything is accentuated. This is why artists like to paint ‘contre jour’, against the light. Not only does it simplify the scene, but it also makes for a more dramatic subject.

When you are painting in situ, be sure to find out the state of the tide and remember that time is of the essence. If you have difficulty in seeing a composition, a simple viewfinder will help isolate the essentials. It is worth spending a few minutes doing a number of thumbnail pencil sketches to confirm your view. Think about and see solid masses, screw up your eyes and see the scene as shapes. Forget that they are boats or buildings at this stage.

The scale you work to is another important consideration. I suggest you start by working smaller rather than larger. I generally use a quarter sheet Imperial paper, but use a half sheet for mixed media – a full sheet measures 56 × 76 cm (22 × 30 in). However, boats are seldom in the right place, so you have to move them in or out of your picture. Do not be afraid to crop them; I often use a stern or bow of a boat to one side in order to frame or help lead the viewer into the picture. Showing part of a boat in this way creates a sense of movement and intrigue, and hints at more beyond the confines of the picture. Degas (1834–1917) found that cropping off part of the subject enhances this effect, so try to study his paintings. Adding a fisherman or seagulls not only gives life to the scene, but scale, too.

When it comes to painting, I am a strong advocate of painting en plein air. A subject like this touches all the senses, and working in situ is a good way of conveying feelings, rather than just images. I also seem to paint much quicker in situ, and produce ‘fresher’ and more spontaneous work than when I am in the studio. When I am working on a painting outside, I find it extremely useful to use a mount to help give me an overview of how the painting is progressing. I also always take a 30 cm (12 in) plastic ruler for checking that angles are correct. I can use it like a mahlstick for rigging as well as using it at arm’s length for checking on horizontals and verticals.

COMPOSITION

Marine subjects are normally painted in a landscape format, but other formats can be challenging and more successful.

Here the emphasis is on the foreground, with the tidepools helping to lead the eye into the picture. I often use the colour, textures and abstract qualities at low tide, to add extra interest to a painting. Remember to avoid detail and keep foregrounds simple.

Good composition has a lot to do with balance and counterbalance. Here the background harbour wall plays an important part in the composition, with the mast also providing a dramatic link. Horizontals and verticals are known to produce a tranquil feel in compositions, while diagonals create more energy and movement.

In these compositional examples, I used a Canson Mi-Teintes pastel paper and drew in felt-tip pen and charcoal. The highlights were put in with white Conté crayon. You will find it less daunting than working on a white paper and it gives you an immediate tonal effect. Think counterchange – it will give rhythm and movement to a picture, as well as providing interesting contrasts.

Polperro Harbour

36 × 26 cm (141/4 × 10 in)

This quick colour sketch was done in situ. I used watercolour and white gouache on a tinted pastel paper (Canson Mi-Teintes – Moonstone). What excited me was the foreground, so I chose a low eye level, to lead the eye into the picture.

Fishing Boats, Polperro

26 × 36 cm (101/4 × 141/4 in)

This colour sketch was done in watercolour and white gouache on a tinted pastel paper. I had to work fast as the tide was coming in very quickly. Although harbours at high tide can make a pretty scene, they are far more difficult to paint than those at low tide.

It is important to get a feel for a place, speak to the fishermen, find out about its maritime history. To really get ‘under the skin’ of a place will take more than one visit.